For this week’s GP Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the awesome 1981 Yamaha YZ465H.

For this week’s GP Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the awesome 1981 Yamaha YZ465H.

In the annals of Yamaha history, few bikes have been as celebrated as the YZ465. Only produced for two years in the early 80’s, the 465’s combination of abundant power, supple suspension, and tight handling, made it the Japanese bike to beat. Even today, YZ465’s are treasured classic racers.

Photo Credit: Yamaha

In the world of vintage motocross, the YZ465 still holds a special place in many riders’ hearts. Yamaha hit the sweet spot with the big 465 and produced what many consider to be the best of the YZ big-bores. Its combination of holeshot-ripping horsepower, tight turning and anvil-like reliability, have made it a staple of racetracks across America for over thirty years. In terms of classic Japanese motocross bikes, the Yamaha YZ465 is a true royalty.

For ’81, Yamaha tried to smooth out the ‘80 model’s massive midrange hit and make the 465 easier to manage. In tinkering with the power, Yamaha boosted the previously lethargic low end, but neutered the mid and top. This made the bike easier to ride, but took away from the holeshot-ripping horsepower that had made the ’80 model so popular.

Photo Credit: LeBig

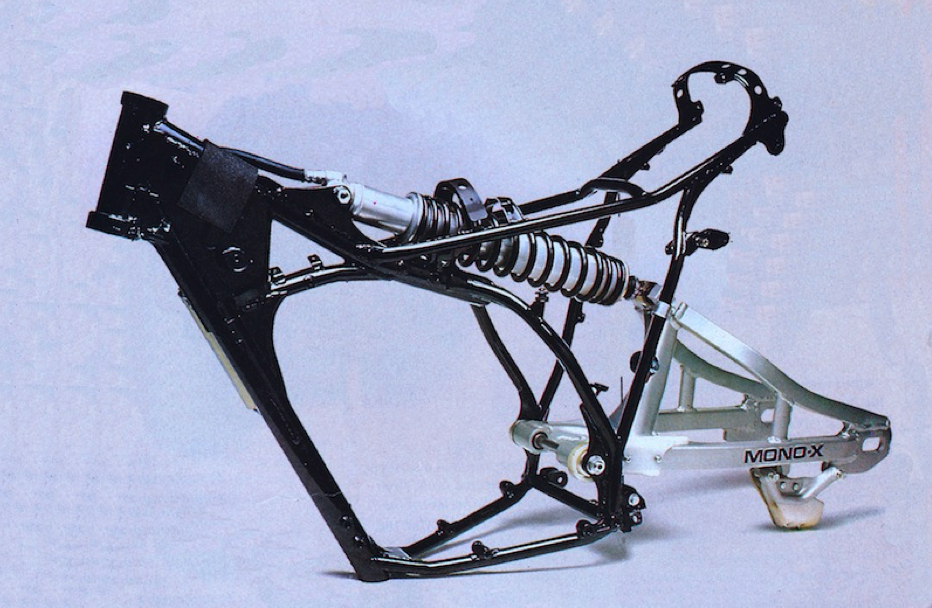

The 1980 YZ465 marked the third generation of Yamaha’s groundbreaking “Monocross” rear suspension system. Originally based on the designs of Belgian engineer Lucien Tilkens, (who had offered the idea to Suzuki first, but had been turned down) the first production “monoshock” debuted on the limited-production 1974 YZ250B and YZ360B. Overnight, Yamaha doubled the available travel on their motocross bikes and dominated the suspension rankings. The monoshock was a revolution in suspension design at the time of its introduction and became the impetus for the suspension arms race that defined late seventies motocross.

At 43 horsepower, the ’81 YZ465 fell behind the mega-motored German and Austrian competition in ’81. The new KTM 495 and Maico 490 both cranked out close to 50 horsepower, and waxed the floor in any race to the first turn. By ’82, the rest of the manufactures would join the Euro’s in bumping up their motors to nearly 500cc. Ironically, this quest for bigger and bigger motors (and scarier and scarier bikes) probably led to the eventual demise of the class.

Photo Credit: LeBig

One feature that was iconic to early eighties Yamaha’s was this big #1 on the plates. In 1978, Yamaha took all three major US titles and as a result, started plastering big #1’s on all the full-size YZ models. Even though they were not able to repeat this feat in 1979, they continued to plaster them on the new machines. Yamaha would continue this odd tradition up until 1986. Photo Credit: LeBig

While the original Monocross suspension was initially a huge step forward, by ’76, the dual-shock LTR (Long Travel Rear) systems on the competition were already beginning to chip away at Yamaha’s lead. Bikes like the all-new Suzuki RM’s offered more travel and better weight distribution than the top-heavy YZ’s. Early mono’s also suffered from a good deal of fade, as the shock’s placement allowed for very little cooling air to reach it. As the decade would come to a close, Yamaha would update their original Tilkiens-concept with features like a stronger alloy swingarm and more compact design. They would also add a remote oil reservoir to aid cooling and punch up the travel to the industry standard 12 inches. With the advent of rear linkage suspension on the horizon, the ’81 YZ465 would be the last stand for the original Yamaha monoshock suspension.

Over the course of their history, Yamaha’s Open class YZ’s had slowly grown in engine size to suit the fashion of the times. From the 351cc of the original YZ360B, Yamaha bumped the displacement up to 397cc in the YZ400C, then to 465cc in the YZ465G and eventually 487cc in the YZ490K. As the motors grew to suit the taste of the times, so did the power characteristics on the big Yammers.

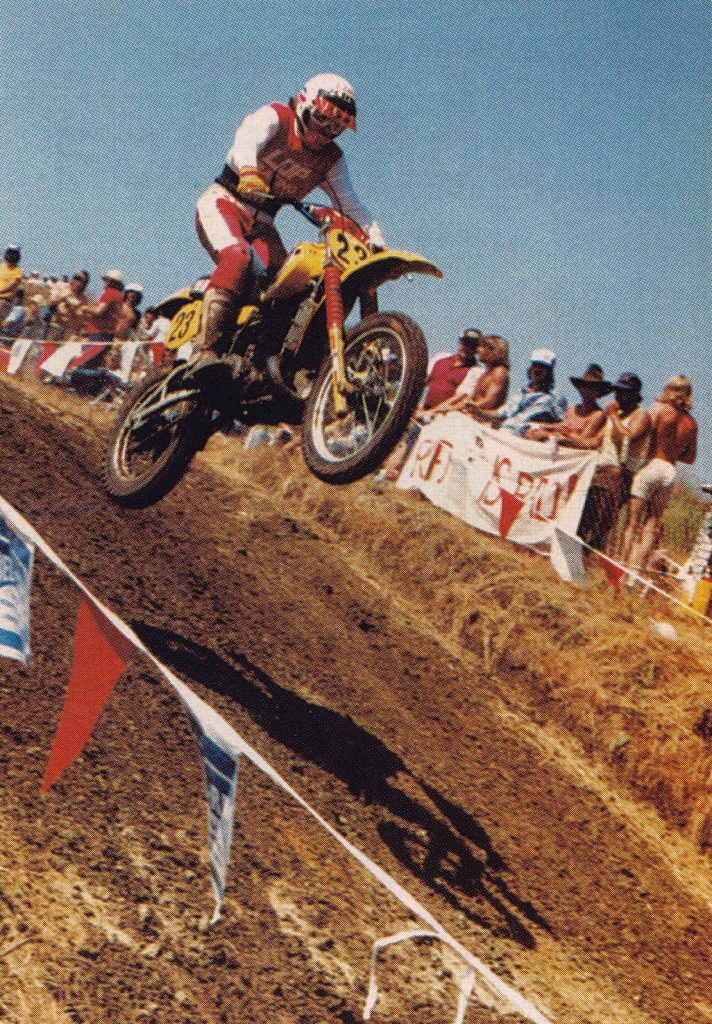

Probably the most famous YZ465 in the World (or at least in America, as some Swedish Carlqvist fans might point out), is this one ridden by Marty Moates at the 1980 500 US Grand Prix. Riding basically a stock LOP Yamaha YZ465, Moates rode away to one of the most shocking upset victories in the sport’s history. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Early Open class YZ’s tended to have punchy and quick revving motors. They were fast, but more akin to bored out 250’s (which they basically were) than stump pulling 500’s. Then in ’79, Yamaha made the decision to go after a more “Maico-style” of power and reconfigured their previously short-stroke two-stroke mill. The new motor retained the same displacement, but featured a different internal configuration. The new long-stroke mill provided the torquey vibes that Open class riders of the time favored, and made the YZ400F (no not THAT one) one of the bikes to beat for ’79. In 1980, Yamaha would go even further in search of the German’s tractor like power, with a bump in displacement to a full 465cc. The new motor would feature a bigger bore and a longer stroke, as well as new narrower engine cases and a smoother-shifting tranny.

When Tilkens originally got the idea for his single shock rear suspension, he grafted a Citroën car shock onto a modified CZ frame to test the concept. Tilkens initially offered the patent to Suzuki, who tested it, but declined to purchase the technology (against the advice of Roger DeCoster and Sylvain Geboers). From there, Tilkens went to Yamaha, who seeing the potential jumped on the design. While the original monoshock was far superior to anything else available in 1972, its high center of gravity and lack of a rising-rate linkage eventually doomed it to the history books.

Photo Credit: Yamaha

The new YZ465G would be an instant success with both the riders and press, taking home the honor of best Open bike of 1980. For 1981, Yamaha would make a few important refinements to the flying four-sixty-five. The new bike would feature a major upgrade in the front suspension, as well as fine-tuning to the motor and chassis. The question would be- would these refinements be enough to hold off a slew of all new competition from Europe and Japan?

1981 was the year of the rear suspension decal. As if by committee, all the manufacturers decided in unison to plaster their rear swingarms with suspension system names. Yamaha had Mono-X (or Monocross, which it had been known by for years, but the bike had never born the name anywhere on it), Honda had Pro-Link (so named for its “Progressive-Linkage”), Kawasaki had Uni-Trak (originally named “Bell-Crank”, apparently Uni-Trak sounded cooler) and Suzuki had Full-Floater (its name derived from its “full-floating dual-linkage” shock design). By the mid-nineties, these nice understated decals would be phased out in favor of purple and pink versions, before disappearing altogether.

Photo Credit: LeBig

While most testers loved the YZ465G in 1980, some riders complained about its hard-hitting and abrupt power delivery. Out of the hole, the “G” model was slightly sluggish, before lighting the afterburners in the midrange and hitting warp factor ten on top. More than a few riders were sent off the back of the big Yamaha as the bikes sudden explosion of power caught them by surprise. For ’81, Yamaha made some subtle changes to smooth out the burly Y-Zed’s delivery. They refined the motor’s porting, rejetted the carb, changed the exhaust pipe and reprogramed the ignition. The result of all this work was a nicer, if slower, 465 for ’81. The new bike came out of the hole with a broader flow of torque, before climbing into a strong, but less violent midrange blast. On the top end, the new motor went flat earlier and demanded to be shifted more (not a great thing on a bike with a notoriously recalcitrant gearbox). It was easier to ride, but less thrilling for the riders who could use the ‘80’s explosive punch. While it was still a competitive mill, it was no longer the holeshot machine it had been the year before. For Yamaha, the real problem was the bike’s increased competition. In ’81, Husky, Maico and KTM all introduced amazing motors that were more than a match for the 465. The YZ gave up as much as nine horsepower to the big-bore competition and went from king of the hill to bridesmaid overnight. It still possessed the best 500 mill from Japan (no great honor in ’81), but was no match for the Teutonic competition.

While the YZ465’s rear suspension may have been getting a little long in the tooth, its front suspension was total state of the art. For ’81, Yamaha upgraded the YZ to a set of massive (for the time) 43mm Kayaba’s. These were the same size as the OW race bikes and a huge improvement over the flexi 40mm units on the ’80 model. They offered 11.8 inches of travel and did an excellent job of smoothing out the track.

Photo Credit: Yamaha

In the suspension department, one of the major upgrades for ’81 was Yamaha’s switch to 43mm front forks. The new Kayaba’s were 3mm larger in diameter than the previous year and a big improvement in steering precision and feel. In ’80, the YZ forks had worked well at absorbing the bumps, but their smallish 40mm tubes were known for flexing badly in ruts and under heavy braking. The new massive (for the time) 43’s provided a precise feel and no noticeable flex. In terms of ride, the new Kayaba’s offered 11.8 inches of smooth and plush travel. They absorbed big hits and small with equal aplomb and were rated the best front forks of any Japanese Open classer. In the overall rankings, only the silky smooth Husky 430CR forks topped the big Yammer.

As the last of the original monoshock Yamaha’s, the ’81 YZ465 stands as the end of an era. While it may not have been as plush as the high tech Full Floater Suzuki, seven years of refinement made it a very solid package. It offered a large range of adjustability and performed better than many of the supposedly more “advanced” competition.

Photo Credit: Yamaha

By 1981, the original Monocross rear suspension design was reaching the end of its development cycle. Early on, the key to Yamaha’s monoshock rear suspension had been its remarkable increase in suspension travel. At a time when the best bikes offered a meager 3-4 inches of travel, the monoshock YZ pumped out nearly twice that. As other bikes jumped on the LTR bandwagon, however, the Yamaha’s advantage dwindled. By the time the YZ465H hit the market in ‘81, the old school Yamaha Monocross was starting to look very dated.

One improvement made to the early mono’s was to add this huge remote oil reservoir to its “De Carbon” shock (named for the French inventor of the hydraulic shock absorber, Christian Bourcier de Carbon). With the shock tucked away from cooling air in the bowels of the motorcycle, the reservoir aided greatly in preventing fading late in a moto.

Photo Credit: LeBig

In an effort to keep up with the competition, Yamaha made some incremental improvements to the rear of the ’81 465. A larger remote oil reservoir further aided cooling on the big mono and an increase in the number of rebound damping settings aided tuning (there was no adjustment available for compression damping). Performance wise, the Monocross offered well-controlled damping and bottoming control. Most riders considered it very raceable in stock form and very good by the standards of the day. It could not compete with the performance and sophistication of Suzuki’s remarkable Full Floater set up, but it was better performing than the Honda and Kawasaki linkage rear ends.

In an effort to keep up with the competition, Yamaha made some incremental improvements to the rear of the ’81 465. A larger remote oil reservoir further aided cooling on the big mono and an increase in the number of rebound damping settings aided tuning (there was no adjustment available for compression damping). Performance wise, the Monocross offered well-controlled damping and bottoming control. Most riders considered it very raceable in stock form and very good by the standards of the day. It could not compete with the performance and sophistication of Suzuki’s remarkable Full Floater set up, but it was better performing than the Honda and Kawasaki linkage rear ends.

One of the improvements made to the ’81 YZ465 was the addition of a folding shift lever. Prior to this, a simple tip over could easily result in a broken engine case or shift shaft.

Photo Credit: LeBig

Another change Yamaha made to the “H” model for ’81 was to tuck in the rake to aid turning. This change, combined with the new beefy forks, gave the YZ very sharp steering response. It was no RM125 in the turns, but for a big and burly 500, it was very nimble. The trade off for this turning precision was, of course, high-speed stability. On fast straights and when coming down from speed, the 465 required a firm grip to prevent having the bars ripped from your hands. On tight tracks the Yamaha was King, but on fast GP style circuits the YZ was a handful.

In terms of braking, these were the six-pot Brembo’s of their day. The dual-leading shoe brakes on the YZ465 (and only on the 465, the 250 and 125 did not get them) could stand the mighty Yamaha on its head with a firm right grip. Until the advent of the front disc, these were the best brakes in motocross.

Photo Credit: LeBig

In 1980, the YZ465 had owned the best brakes on the track with their advanced dual-leading shoe brakes (they were only on the 465, all the other YZ’s had to make do with old school single action drums). In ’81, many of the YZ’s competitors followed their lead and moved to the dual action binders. In the days before disc brakes, these were the state-of-the-art in motocross stoppers and a huge improvement in stopping force. In 1980, the brakes were so powerful that riders complained of binding in the front end under braking, because of all the flex in the spindly front forks. The switch to the jumbo 43mm Kayaba’s in ’81 remedied this problem and gave the Yamaha class leading stopping prowess.

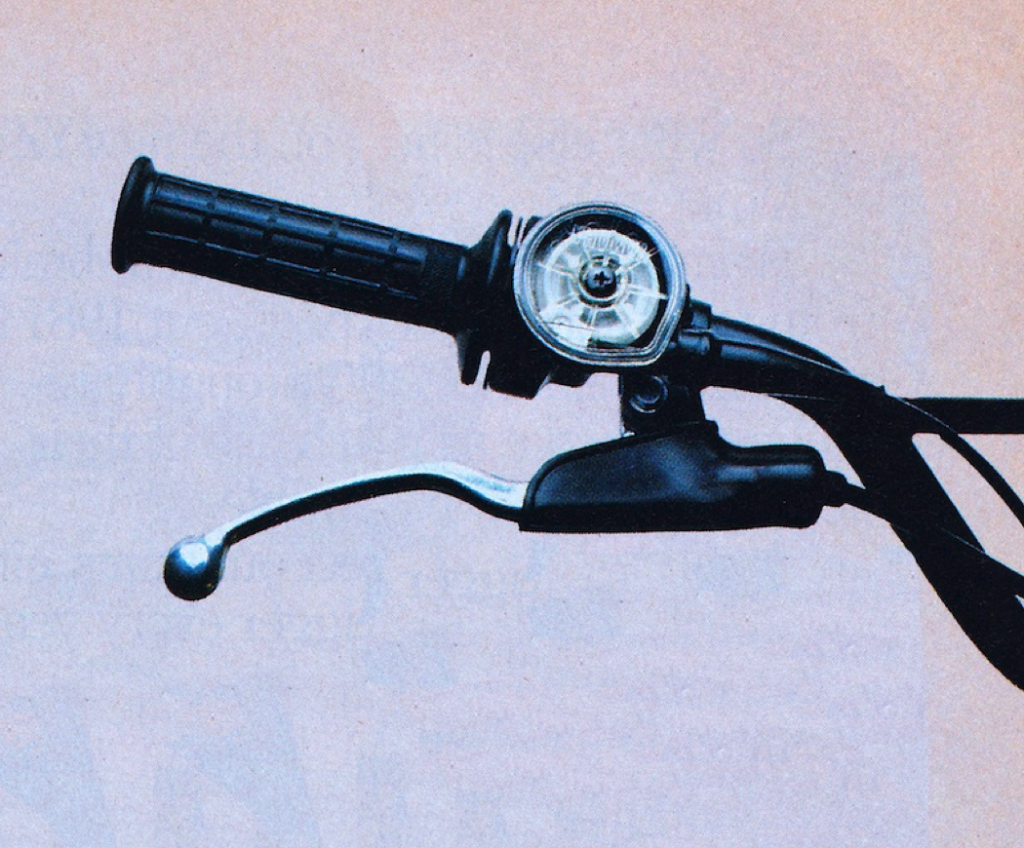

Today most riders do not even give their throttle a second thought, but in ’81 this baby was big news. The new ’81 YZ’s were the first Yamaha’s to come standard with a side-pull “whirlpool” style throttle. These had been popular aftermarket additions for years with companies like Gunner Gasser becoming household (in motocross households anyway) names. Yamaha was so proud of their new toy that they actually saw fit to add a clear top to the throttle so you could see the cam thingy spin around (I wonder if the owners manual warned riders not to watch it while riding?).

Photo Credit: Yamaha

Some other interesting additions were made to the ’81 YZ’s that we all now take for granted. This was the first year Yamaha moved to a “side pull” throttle assembly. This meant the throttle cable exited out the side of the throttle housing instead of sticking straight up a foot in the air, before turning back down to the carb. This made for a much cleaner design and led to far fewer problems from snagged cables (I know this seems trivial now, but it was a big deal in ’81. Gunner Gasser made a lot of money selling whirlpool throttles to riders prior to this). Another item common today that was coming into fashion in ’81 was the folding shift lever. Prior to this simple, but imminently useful little bit of engineering, a minor tip-over could result in a bent shift shaft and cracked engine cases. With the advent of the folding tip, that energy was no longer transmitted directly to all the hard-to-fix and expensive components.

In 1980, Yamaha ruled the motocross world with their stunning YZ465. In ’81, they took two steps forward, but one step back and the competition caught up to the mighty 465. Its “friendlier” motor and old tech suspension were no longer enough to keep the big YZ at the top step of the podium. Still, at $2149 it was substantially cheaper than the Euro competition and when you factored in its unbeatable aftermarket support the gap narrowed even more. The YZ465 may not have been the fastest bike you could buy in 1981, but thirty years later, it is probably the best bike to buy of its era.

Photo Credit: LeBig

Even today, the YZ465 stands as the high water mark for Yamaha two-stroke Open bikes. For the two years the Yamaha reigned supreme at the head of the Japanese 500 class, it was not uncommon for 70% of the bikes at a local race to be YZ465’s. They were fast, reliable, well suspended and far less expensive than the Euro competition. When you threw in all the aftermarket and dealer support available, the YZ became very hard to beat. After ’81, Yamaha would punch out the 465 to a 490 and begin a long string of underwhelming machines. It would not be until seventeen years later, with the introduction of the revolutionary YZ400F four-stroke, that Yamaha would once again build the best open bike in Motocross.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram – @TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com