We did the best bikes ever, now it’s time for this.

We did the best bikes ever, now it’s time for this.

By Tony Blazier

(for the list of the bikes that changed motocross, click HERE)

Welcome to the golden age of motocross performance. Today’s bikes are by far the best performing machines ever offered for sale. They offer power, handling, and ease of use unimaginable in even $50,000 factory racers from a decade ago. No matter what brand you select or what type of motor you choose, you are virtually guaranteed to end up with a quality product. That was certainly not always the case.

Over the years there have been some truly awful bikes proffered on the buying public. Some were so terrible they have gone down in the annals of motocross lore like some sort of mythical creature. The very mention of their names would conjure visions of carnage and mayhem. Others, while not completely terrible, were so flawed in one way or another to be virtually useless as competitive racing machines. The history of motocross is littered with the tales of these terrible bikes.

When I set out to document these engineering tragedies I laid down a few ground rules. I decided to limit my selections to motocross racing machines only (the Honda Fat Cat lives to fight another day!). I also wanted to be fair and only compare the machines to bikes from their own era. By today’s standards pretty much any bike built before the mid-nineties would seem terrible, so keep that in mind when you read my selections. The seventies and early eighties, in particular, produced some really sub-par machines as the manufacturers tried to figure out what worked and what didn’t on a dirt bike. This really was the Wild West in terms of design and the manufactures tried all kinds of crazy ideas on the bikes. Some innovations like reed valves stuck, while others like “boost bottles” faded away into obscurity. This incredible period of technological innovation gave birth to some of the most iconic machines ever to lay rubber to dirt. It also produced some of the biggest turds ever to foul a plug. This is their story.

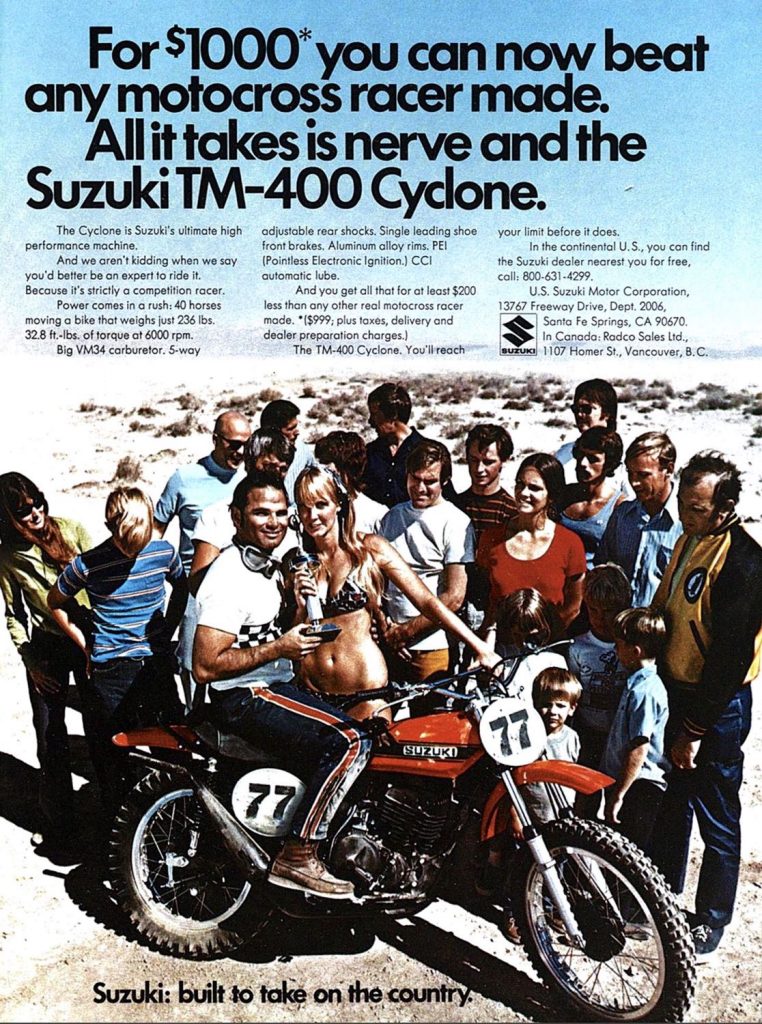

The trophy was for survival. Photo Credit: Suzuki

1 – The 1971 Suzuki TM400 Cyclone

At number one with a bullet, we have without a doubt one of the most terrible and infamous motorcycles ever produced, the 1971 Suzuki TM400 Cyclone. The TM400 was produced by Suzuki from 1971 thru 1975 and was Suzuki’s premier race machine at the time. The Cyclone’s horrible reputation was founded on its handling and power delivery, both of which left a lot to be desired. On paper the Cyclone didn’t look too bad, costing a reasonable $999.00 and putting out a claimed forty horsepower. Those forty horses were not of the easy to use variety, however. The power was basically a light switch with an all or nothing delivery. Compounding the abrupt power was a crude and unreliable ignition system that would cause the bike to run erratically at times and greet the rider with a sudden and unexpected burst of power. Sometimes the power would kick in at 3500 rpm, sometimes it would kick in at 5500 rpm, and sometimes it would just sputter and cough (and you thought modern bikes were trick with thier variable ignition programs, Suzuki had it in ’71!). Unfortunately for the unsuspecting TM400 owner, the fun did not stop there.

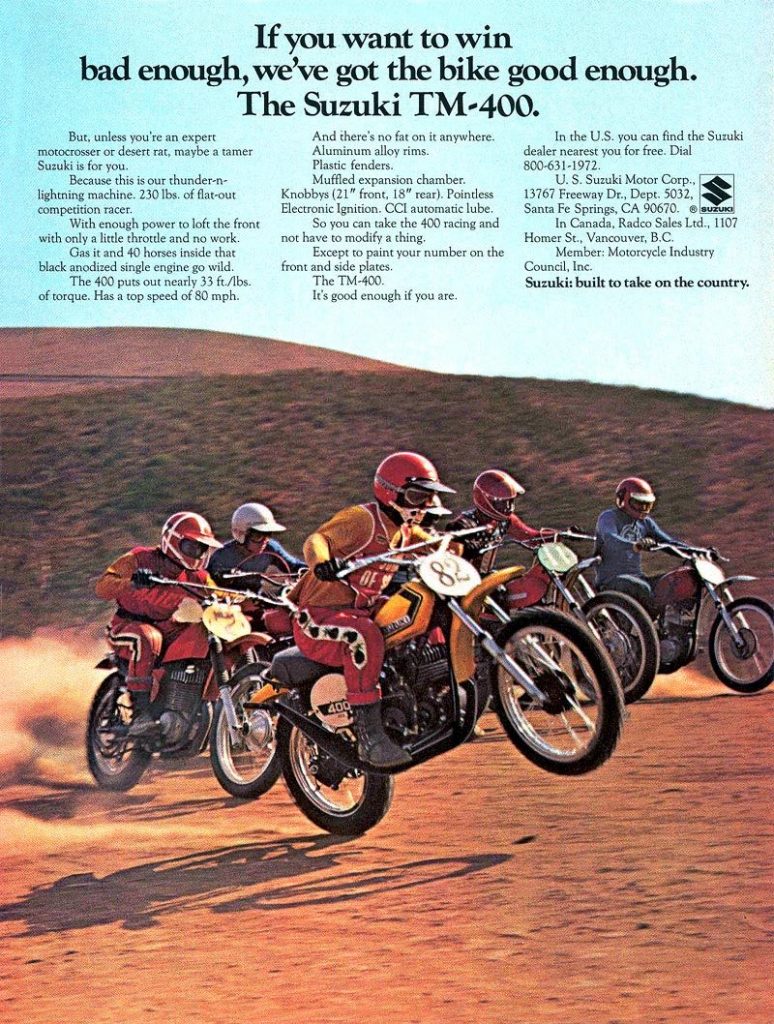

Warning: Objects in this ad may be crappier than they appear. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The TMs were marketed by Suzuki as a replica of the all-conquering Factory racers ridden by Joel Robert and Roger De Coster in Europe. The Cyclone in actuality weighed a good fifty pounds more than Roger’s Factory bike. On top of being horribly overweight, the Cyclones’ chassis was an ill-handling mess. The forks appeared to use internals stolen from a Bic pen and shocks would last about ten minutes before trying to eject the rider into orbit. About the best thing you could say about the Cyclone’s suspension was that it did hold the bike up when stationary. The frame on the Cyclone did not help matters as it flexed so badly it would bind up under a load and then snap back like a spring when the rider rolled off the throttle. This usually resulted in the unsuspecting TM400 rider launching himself into the weeds…or worse. By 1975 Suzuki had managed to exorcise some of the Cyclone’s worst traits out. The motor became easier to manage and the handling was improved a small bit. By that time, however, the die had been cast and the TM400 Cyclone was thoroughly entrenched in the minds of the motocross community as a dangerous and scary machine. In an era filled with unreliable, crude, and generally crappy motorcycles, the TM400 was the crappiest of them all.

And you thought three-wheelers were dangerous. Photo Credit: Yamaha

2 – The 1973-1974 Yamaha SC500

Yamaha has had a long, checkered past in the open class. Their open class offerings have run the gambit from awesome to gruesome over the years. For every fantastic YZ465, we would have an equally dismal YZ490 to counterpoint it. Even Yamaha’s current YZ450F has been a source of much hand wringing and debate since its introduction in 2010. For Yamaha, the open class has been a forty-year roller-coaster ride of success and failure. Since every roller-coaster ride must start at the bottom it is appropriate that we start right here, with the 1973 SC500 Scrambler. The SC500 was Yamaha’s first attempt at a 500cc motocross machine. Weighing in at a rather porky 243lbs, the SC500 featured an air-cooled 498cc reed valve two-stroke single mated to a four-speed transmission. Handling the suspension duties were a pair of remote reservoir rear shocks and a set of inline axle front forks offering a good for the time four inches of suspension travel.

This is what passed for freestyle in 1974. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

If there was one word that best described the SC500 it would have to be grim. Pretty much everything about this bike was terrible. The big 498cc single was virtually impossible to jet correctly. It would sputter, cough, and stall constantly. The throttle response was notoriously terrible and one tester at the time described it as having less low-end power than a good running 125. The SC500 delivered all of its considerable forty horsepower in one big explosive midrange rush that sent the front end skyward before quickly tapering off into a non-existent top-end. Adding to the motor misery was a propensity to overheat and seize at regular intervals (Yamaha should have offered pistons in six-packs for convenience). The SC’s chassis was an even bigger disaster than the motor. The SC500 suffered from poor weight balance resulting in an overly light front end. As a result, the bike wanted to wheelie constantly and would wash out the front end in corners. At speed, it would shake its head violently enough to rip the bars from your hands and swap side to side as if it had a hinge in the middle. The forks were terrible even by 1973 standards and beat the rider to death over every bump. The high tech looking remote reservoir shocks were just as bad and would fade after 5 minutes bounding up and down like a pair of pogo sticks.

A contemporary Cycle magazine test put it best when describing the SC500. They commented that Yamaha got all the minor things right on the SC500 but totally missed the boat on the big important ones. Unlike its European rivals all the plastic fit right and none of the parts fell off, but the bike’s performance was terrible. By contrast, the European bikes were all fragile and finicky but handled and performed light years ahead of the Yamaha. The European’s lead would not be long-lived however as Yamaha and their Japanese counterparts would quickly figure out how to get the big things right as well. Within a year of the lowly SC500’s release, Yamaha would shock the world with its incredible YZ360 Monoshock and change the sport of motocross forever.

|

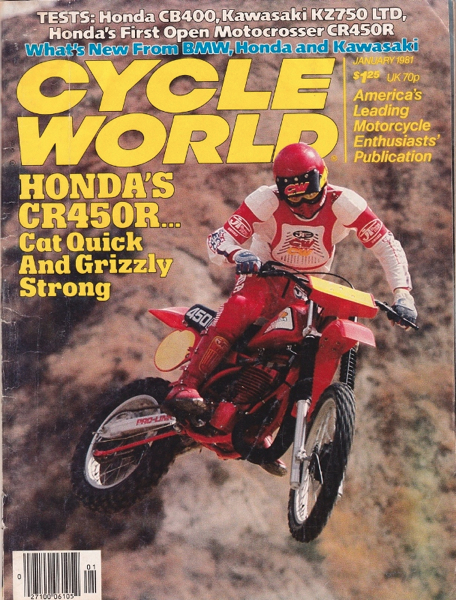

| A cover that would live on in infamy. Photo Credit: Cycle World |

3 – The 1981 Honda CR450R

What we have here is one of the most anticipated motorcycles ever produced, the 1981 CR450R. In 1980 the excitement surrounding the impending release of Honda’s first Open class bike was reaching a fever pitch. The hype machine was in full swing and the buying public was waiting with checkbooks ready to plunk down their hard-earned cash on the fastest, nastiest ground pounder ever to throw a roost. What they got instead was one of the most confused and disappointing machines ever to hit the showroom floor.

Honda had begun producing lightweight two-stroke race bikes in 1973 with their revolutionary CR-250M. The CR-250M helped usher in a whole new era of high-performance Japanese race bikes in the seventies. Honda, Yamaha, Kawasaki, and Suzuki made quick work of their European counterparts, gobbling up market shares in mighty chunks. By the end of the decade, the Japanese had a near stranglehold on the American motocross market. Throughout this explosive growth period, Honda had resisted building a true Open class race bike. They had stuck to producing 250cc and 125cc machines only. This is noteworthy because motocross in the seventies was very different than it is today. In the late seventies, the European Grand Prix’s were still considered the pinnacle of motocross racing and in Europe the 500 was King. By not producing an Open class bike Honda was left with a huge hole in its portfolio.

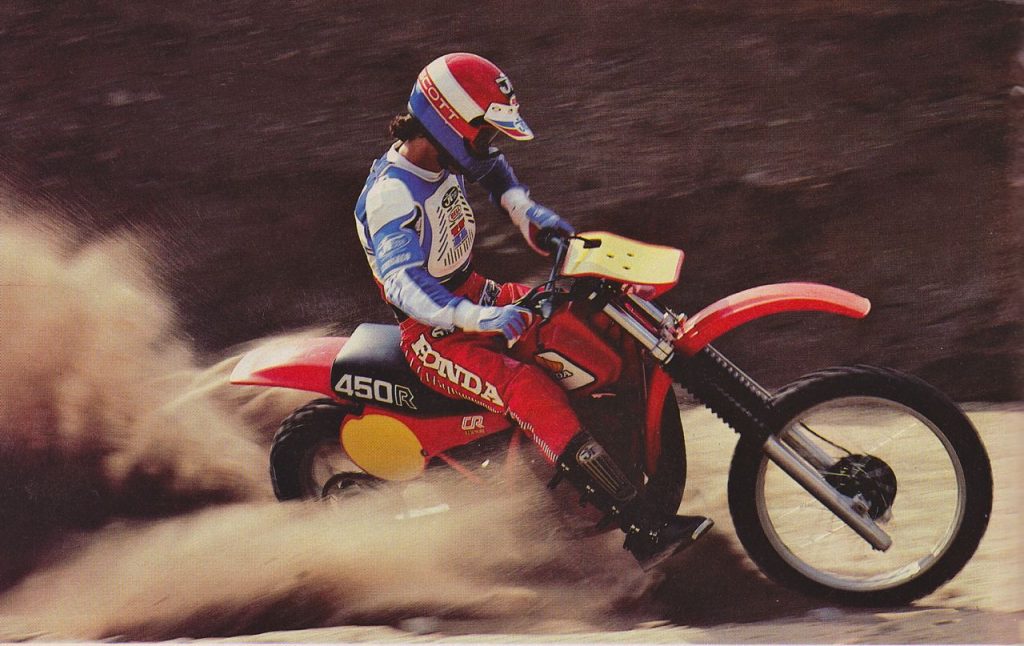

The mighty 450 awaits another victim. Photo Credit: Cycle World

The mighty 450 awaits another victim. Photo Credit: Cycle World

Even though Honda did not produce a production Open class bike they were not prepared to totally ignore the 500 GP’s. Honda produced a few prototype 500cc race bikes for stars like Brad Lackey, André Malherbe, and Roger De Coster to race in the Grand Prix’s and Nationals here in the USA. These super trick RC500s only served to further whet the buying public’s appetite for a Honda production Open bike. In 1980 in fact, Honda RC500s took home both the 500cc Grand Prix title and the 500cc National motocross title in the USA. It was in this climate of completely unrealistic expectation that the 1981 CR450R made its debut.

Is that a snow shovel on your bike or are you just happy to see me? Photo Credit: Cycle World

When the production CR450R finally made its appearance in the fall of 1980, it certainly looked the part of a serious race machine with its racy bodywork and screaming red paint job. The bike was all-new from the wheels up and featured Honda’s first production monoshock suspension. Honda called their system Pro-Link and it is actually very similar in design to what we still use today. Handling the suspension duties on the 81 450R was the odd combination of a Showa rear shock and 41mm Kayaba front forks. The 450Rs all-new bodywork looked very modern and sleek with the exception of the most unfortunate front number plate ever hung on a motorcycle. I can only assume the ridiculous shape was an attempt to get more air to the motor. Whatever the reasoning behind it, Honda should have never let it see the light of day. It got compared to everything from a hangnail to a snow shovel and became something of a symbol for the inept performance of the much-maligned 450R.

The heart of any race machine is its motor and that is really where Honda shot itself in the foot. The CR450R’s motor was in a word, terrible. The 450R was actually not really a 450 at all but rather a smallish 431cc. Instead of crafting a purpose build open class motor Honda had basically bored and stroked their existing CR250 motor out to 431cc to turn it into a big bore. To make matters worse Honda made the dubious decision to install a four-speed transmission in the bike instead of the more versatile five-speed. The result was a total disaster.

The CR450R ran like a big 125 with a very narrow spread of power and a very light flywheel. It would explode suddenly in an uncontrollable rush of wheel spin and just as suddenly fall flat on its face. The powerband was razor-thin and when combined with the hopelessly spaced four-speed gearbox the bike was virtually impossible to ride. The peaky 431cc motor was easy to stall and required a lot of clutch abuse to overcome the oddly spaced transmission. Unfortunately, the clutch was not up to the job. The clutch would grab, lurch and eventually start slipping like a two-speed Powerglide. 1981 CRs were infamous for creeping forward even if the clutch lever was fully pulled in. The clutch would decide it was time to go whether you liked it or not. The 450R’s motor also had a very un-Honda like habit of blowing up (did I mention this motor was a piece of crap?).

The big Honda’s chassis and suspension were not much better than the motor. The bike would headshake at speed like a wet dog getting out of a bath. The Showa shock was too soft initially, and then it would hammer your spine when the rising rate linkage kicked in. The mismatched Kayaba forks would bottom out over anything bigger than a candy bar. About the only thing, the ’81 CR450R did well was turn. If you could harness the rest of the bike it would carve a nice inside line.

They say you only get one chance to make a first impression, but thankfully for Honda, the buying public forgave them for the tragedy of the 1981 CR450R. By 1982 Honda fixed most of the shortcomings of the ‘81 450R and introduced a bike that is still beloved to this day, the CR480R. The CR480R was everything the CR450R had not been and it went a long way toward repairing Honda’s tarnished reputation. Best of all, someone had the sense to drop kick that ridiculous number plate. That alone is worth two horsepower in my book.

|

| This thing knocked worse than a diesel Chevette with water in the tank. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

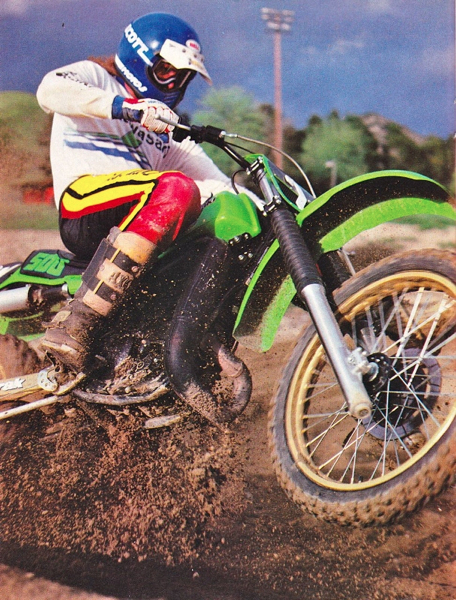

4 – The 1983 Kawasaki KX500

There is almost a magic to making a big bike work. A chassis that works like a dream on a 30hp 125 will become an unruly beast when mated to a 60hp big bore. It is a true test of engineering know-how to turn a 500cc brute into a manageable machine. In the early eighties, it was a test a lot of the Japanese manufactures were failing miserably.

In 1980 Kawasaki had introduced an all-new big bore to compete with the all-powerful Maico Open bikes. The big German was THE bike to own in the Open class at the time, combining a sweet tractor like power delivery with excellent chassis dynamics. Kawasaki’s attempt at a Maico beater had been a miserable failure. The KX420 was overweight, less powerful, poorer handling, and incredibly, more fragile than the notoriously finicky German. The big KX420 was such a disaster that Kawasaki completely threw in the towel and did not even attempt to make a 500 class bike for ‘82.

This brings us to the subject at hand. Kawasaki’s all-new and fully two years in the making, 1983 KX500. You would perhaps be right in thinking that if a company takes a year off to regroup and comes out with an all-new model, it should be better than the one that had caused them to quit in the first place. Well, in this case, you would be wrong. In almost every way the ‘83 KX500 was actually worse than the much-maligned 420 had been. Kawasaki had taken a sow’s ear and instead of turning it into a silk purse, came back with a whole pig.

This bike was bad, so bad in fact none of the magazines could even test it in stock form. The ’83 KX500 had a motor so poorly designed that it would blow itself to pieces in the matter of a few laps. The big 500 Kawasaki was saddled with a terminal case of the knocks and if left unchecked, it would literally beat itself to death in short order. Once the motor got a little hot it would start rattling like it had a box of marbles loose inside it. If you ignored the death rattle, the next sound you would hear was a very expensive bang, as big pieces of aluminum became little pieces of aluminum. This baby was a grenade with the pin pulled.

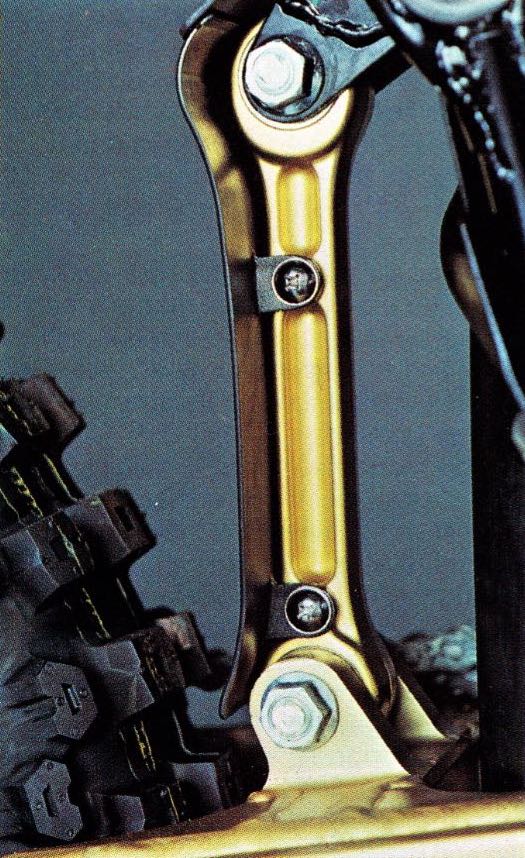

Nothing like a 12-inch golden rod to impress your riding buddies. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Big bore two-strokes are a temperamental bunch by nature. Something about that huge piston makes the monster motors much more difficult to set up. In the seventies and eighties, virtually all the manufactures struggled to get these big bikes to run correctly. Yamaha in fact spent the entire decade of the eighties trying to get their YZ490 to run cleanly only to finally give up and quit the 500 class altogether. A huge problem on these air-cooled 500s was detonation, or “knocking” as it is often called. Knocking occurs when the pressures and temperature in the cylinder reach the point where the fuel charge can spontaneously ignite out of time with the normal combustion cycle. If this occurs, severe motor damage can be the result. The ‘83 KX500 was the poster child for this unfortunate malady.

On the KX, the only fix was to send out the motor to be reworked. If left stock, it was hopeless. Riders tried everything from going richer on the jetting to altering the ignition timing to get the big green pig to run correctly, but nothing worked. While the KX was still in one piece the motor was a hard beast to ride. It blubbered off idle and then exploded violently as the revs climbed. When it climbed onto the powerband it was best to hold on tight and make sure you were pointed in the right direction. This motor was the very definition of violent. As was typical of most big bores of this era, there was very little top-end pull after the monster midrange. If you revved out the big KX all you were greeted with was more death rattle and worse vibration than a Harley with loose motor mounts.

As is fitting with any truly terrible bike the chassis was only mildly better than the motor. The ‘83 KX was a very tall bike. With a seat height of 39 inches, it would be a skyscraper even today. This meant anyone fewer than six feet tall would find it virtually impossible to start the unruly beast without the help of a hill or milk crate. Once you got the jolly green giant moving you would find that the tall height translated itself into a very high center of gravity. This lent the KX a very top-heavy feel that made the bike very hard to turn. Contributing to the poor handling was a badly set up shock that was over-damped on compression and under-damped on the rebound. The 43mm Kayaba forks were marginally better than the pathetic shock but too soft for the weight of the big 500. This combination of soft forks and overly stiff shock gave the Kawasaki the perpetual stinkbug stance that is the hallmark of finer handling machines everywhere.

That rear fender alone is enough to earn a place on this list. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

I know styling has nothing to do with performance but I have to mention the fact that the ’83 KX500 had one of the stupidest looking rear fenders ever put on a motorcycle. I know KTM started this ridiculous trend of sticking your rear number plate on the fender, but I blame Kawasaki for trying to make it mainstream. Anyone who has ever had the misfortune of touching a hot exhaust would no doubt question the wisdom of leaving the hottest parts on the bike exposed as well (ugly and dangerous…what a combination!). I’m also not so sure about that gold swingarm. I know it was the go-go eighties and all, but….

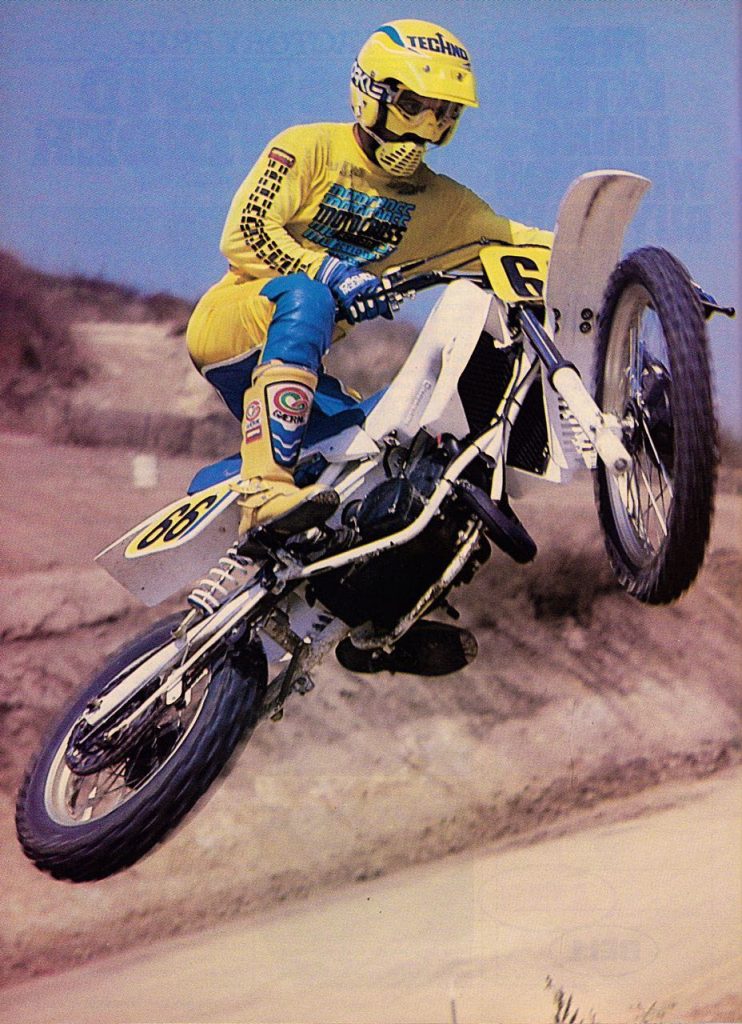

230lbs of Swedish awesomeness. Photo Credit: Husqvarna

5 – 1984 Husqvarna 125 CR

Husqvarna has a long and storied history in the sport of motocross. They have seen the highest of highs and the lowest of lows. Along the way, Husky has turned out some of the greatest racing machines in the sport’s history. This, however, does not happen to be one of them. I give you a bike time has forgotten, the utterly dismal 1984 Husqvarna 125CR.

Husqvarna Motorcycles started out like many motorcycle manufacturers, as a bicycle builder. It was founded in the town from which it derives its name, Huskvarna Sweden in 1903. Its parent company Husqvarna Armament had been a military supplier to the Swedish army since the late 17th century. Over the years Husqvarna had diversified its portfolio to include other products such as motorcycles and chainsaws. Husqvarna’s bicycle business grew from little more than a hobby in 1903 to one of the premier motorcycle builders in the world by the 1950s. Their lightweight two-stroke racers dominated motocross and off-road racing throughout the sixties and seventies, taking home sixteen World Motocross titles and countless off-road championships. Their dominance played a major role in the rise of the two-stroke motor in off-road racing in the sixties. Up until that point, motocross had been dominated by big British four-strokes from companies like BSA. The new lightweight two-strokes from Husky and CZ quickly made these four-strokes obsolete.

Slowly, however, Husky lost its dominant position. As the seventies came to a close the once-powerful marque began to fall behind its Japanese competition. By the early eighties, Husqvarna had become little more than an afterthought to the American motocross community and with bikes like the 84 125CR, it is not hard to see why.

I think Husky stole the motor off one of their chainsaws. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

One look at the 1984 Husky 125 and you can see it belongs in another decade. Everything from the dual shocks to the spindly swingarm screams the SEVENTIES! The hopelessly outdated Husky used various parts from Husqvarna’s parts bin like some machine out of Winners Take All. The motor was a design from the late seventies and its only conceit to modern technology was liquid cooling. You have to remember that this was the early eighties and unlike today, the manufacturers were completely redesigning their bikes virtually every year. The Husky’s five-year-old motor might as well have been from the Stone Age. Case reed intake? Nope. Power valve exhaust port? Power what?!? Horsepower? Not hardly. To give you an idea of how pathetic the poor Husky’s motor was, it lost out in a power ranking to one of the all-time slow bikes, the 1984 YZ125. The 1984 YZ125 would have had a hard time giving a Toro lawn mower a run for its money, so you know this little Swede was gutless.

Further handicapping the Swedish tiddler was Husqvarna’s decision to place the anemic motor in their 250CR frame. Really the only advantage a 125cc bike has over its bigger brothers is its lighter weight and superior handling. That is the reason most people choose to ride the underpowered but fun bikes. Well, Husky in their infinite wisdom chose to shoehorn their geriatric 125 engine into their much beefier 250 chassis, thus negating the 125’s only real advantage. In a class where most bikes flirt with the 200lbs range, the Husky tipped the scales closer to a rubenesque 225lbs (nothing guarantees performance like underpowered and overweight!).

The Husky’s suspension was just as dated as its motor. By 1984, every manufacturer was using a monoshock rear suspension with some kind of rising-rate linkage, everyone but Husqvarna that is. For some reason, Husky had stubbornly held onto their seventies-era dual shocks in the face of superior designs. Even if they had actually worked better (which they didn’t), the duals made the bike look like an escapee from another time and did the bike no favors in the court of public opinion. Out front, the Husky made do with a pair of undersized 40mm front forks mated to a completely worthless drum brake. By 1984 both of these features were already outdated. Most of the Husqvarna’s competition had already moved onto markedly superior disc brakes and a sturdier 43mm set of forks. As for handling performance, the Husky was about what you would expect from an underpowered 125 with an obsolete, overweight 250 chassis. It liked to go straight and little else. Turns were a mere afterthought to the old school Swede. In typical for-the-time Euro fashion, the Husky sat very tall and had controls sized more for a full-grown man than the average 125 pilots of the time. The end result was a bike fitted to a rider it lacked the power to pull around. In short, this bike was just a mess from start to finish.

The 1985 Husqvarna 125CR was all-new and much improved, but far too little too late to save the Swedish brand from its imminent sale to Cagiva. Photo Credit: Husqvarna

The following year Husky would finally make its way into the eighties with an all-new 125 featuring a monoshock rear end and disc brake. Unfortunately, it was a case of too little too late for the once-proud Swedish brand, as it would be gobbled up by Italian powerhouse Cagiva in 1987. The resulting Husqvarna’s were little more than white and blue Cagiva’s. It was a sad outcome for a once-proud marque.

It took the talent of Magoo just to keep this monster on two wheels. Photo Credit: Honda

6 – The 1984 Honda CR500R

In 1981 Honda launched its first Open class motocross bike, the aforementioned CR450R. After consumers and press alike shunned the 450, Honda had the good sense to go back to the drawing board for 1982. The result of this rethinking was the much-improved 1982 CR480R. The 480R got rid of the 450R’s narrow, hard to use powerband and replaced it with the luscious torque and low to mid-range power delivery that Open class bikes are famous for. As a reward for their efforts, Honda took home victories in all of the magazine shootouts for 1982. In 1983 Honda built on the success of the ’82 480R with the addition of a fifth gear for the transmission and all-new ultra-sleek bodywork. The ’83 CR480R turned out to be an even bigger success than the ’82 CR had been and Honda once again dominated on and off the track. For the 1984 season, Honda’s goal was to fix the minor complaints people had with the ’83 CR480R while not losing its class-leading performance. Unfortunately for their customers, they failed miserably on both counts.

The 1983 CR480R, while extremely popular had not been perfect. The majority of complaints were centered on its low to mid-power delivery. The ’83 480R had a very punchy delivery with a lot of torque but very little top-end power. It was a short shift motor that would run out of steam if revved out. This kind of motor worked great for Open class racing where control is sometimes as important as sheer power. Even so, some riders complained about the 480’s lack of top end. Honda decided to go in search of more top-end power for 1984.

Unfortunately, the warfare was on the buying public. Photo Credit: Honda

What this search produced was one of the scariest bikes of all time, the 1984 CR500R. For 1984 Honda threw out everything from the class-leading ’83 480R. The 491cc motor was a clean-sheet design and shared not a single part with the ’83 model. Even the kickstarter was on the opposite side. The motor was bolted to an all-new chassis and covered in new bodywork once again. For added bonus, Honda added a much-needed disc brake to the front to help slow the mighty 500 down (if there is one thing this bike needed it was brakes).

The ’84 CR500R certainly had the looks of a winner. The orange and blue color scheme introduced on the ’83 models still looks great today and the CR’s bodywork was so far ahead of its contemporaries it appeared to be from ten years into the future. As they say though, beauty is only skin deep and this bike had serious problems lurking underneath those matinee idol looks.

The problems started right off the bat with the big CR500R. The bike was nearly impossible to start. Cold it would take a good ten kicks to get the beast to light. If it was hot you could double that number if it would light at all. You have to keep in mind too that this was no 125 you were kicking. These bikes required a real kick. I mean a literally jump up in the air and bring all you weight down kind of a kick. About a third of the time the stubborn five-honey would kick back and god helps you if you were stupid enough to not be wearing boots. Broken kickstarters were a regular occurrence.

If you ever got the CR500R running you were in for one of the all-time thrill rides in motocross. This thing was the Top Fuel dragster of 500’s. Where the 480R had been mellow and easy to manage the 500R was brutal and terrifying. Carburation had always been a huge problem on these air-cooled dinosaurs and the ’84 CR500R was no exception. The 500R was impossible to jet correctly. No matter how much brass you swapped out the bike would not run cleanly. It would blubber and sputter down low and rattle and ping on top. The motor would stumble and hesitate when you rolled on the throttle then suddenly clean out as it climbed into the midrange and took off like a Saturn V rocket. This terrifying transition from bog to afterburner made the 500R a handful for even the most skilled of riders. It was virtually impossible to get the bike to hook up and it would spin wildly out of corners. If it actually caught a little traction it would invariably try to loop out. If you got the Honda anywhere near loamy dirt or sand it would overheat and seize in short order (maybe they stole the motor design from Kawasaki). This motor was a handful for experts and a death wish for lesser talents.

Adding to the ’84 CR’s thrill a minute experience was a chassis that just could not cope with the 500R’s howitzer like power delivery. If you swapped the stock Keihin carb for a Mikuni and sent the motor out to be fixed you would find out the ’84 CR500R actually was a pretty decent handling bike. Once modified it turned pretty sharply for a 500 but suffered from severe headshake at speed. If you left it stock, all you had was the nasty headshake. The stock engine’s herky-jerky power delivery made the bike virtually impossible to control.

Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead! Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The suspension on the 84 CR500R did little to help harness the big bike’s nasty disposition. In 1984 Showa was yet to produce a decent set of forks and the 84 CR kept the streak going (it would take the cartridge units on the 86 CR’s to finally change that perception). The forks were badly under-sprung for the 500’s weight and would bottom out constantly without modification. The shock was just as badly under-sprung and would wear out faster than the rear tire. On top of its lackluster performance, the shock had a rather annoying habit of blowing its remote reservoir hose clean off the shock body. Most pros just ditched the shock completely and installed an aftermarket alternative.

The 1984 CR500R was such a rousing success that Honda scrapped it at the end of the year and introduced an all-new CR500R for 1985 (Can you imagine a manufacturer coming out with an all-new bike today and then completely redesigning it only one year later?) This time the big Honda featured liquid-cooling and much-improved carburation. While still a brute, the ’85 was a huge improvement over the one-year disaster of the ’84. The 1984 CR500R will forever go down in history as one of the scariest Honda machines ever produced.

A rare sighting of the flying Turdus Maximus. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

7 – The 1985 Yamaha YZ125

The early 1980s were not a great time for Yamaha. The tuning fork company had been a major player in the seventies with great bikes and multiple Supercross and National Motocross titles coming their way. In the early eighties though, Yamaha really lost its way. The excellent machines of the late seventies gave way to the overweight troublesome turds of the early eighties and Yamaha started losing market share and titles to its competition. The low point of this downward spiral is probably the machine you see here, the epically terrible 1985 YZ125.

Yamaha had been roundly ridiculed for the performance of their 1984 YZ125. The ’84 YZ125 was pathetically slow but handled well and was a decent novice bike. For 1985 Yamaha claimed they were going to remedy the ’84 bike’s woeful performance and be back at the top of the 125 heap. Yamaha Racing team manager Kenny Clark famously stated “We will not have a slow 125 in 1985” at the end of the 84 season. I’m not sure the R&D department got that memo.

The 1985 YZs were the first bikes to adopt the white and red color schemes found on Yamahas in Europe. The fresh colors made the bike look a lot newer than it really was. Underneath the flashy new paint job was basically the same bike that had underwhelmed riders from coast to coast the year before. About the only real improvement, Yamaha made over the ’84 YZ125 was the addition of a disc brake. Other than that, it was the same old turd that had been the brunt of so many jokes the year before.

So how bad was the 1985 YZ125, really? How about last place bad, as in last in every category bad. In Dirt Bike’s 1985 125 shootout, the lowly Yamaha ran the table by finishing at the bottom in every category but braking performance. This was not in a three-bike shootout either. Dirt Bike compared six 125s for this competition including perennial also-rans KTM and Cagiva. The Yamaha could not even beat any of them.

The 1985 YZ125 certainly looked fresh and new but its new coat of pain belied its moldy-oldy performance. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The ’85 YZ125 motor was slow to the point of being an embarrassment. On the dyno, this pathetic leaf blower pumped out an anemic 21hp. This is when class leaders like Honda and Kawasaki were getting 26hp out of their stock 125s. To put that in perspective the mighty ’85 YZ125 was putting out about half what a modern KTM 125SX pumps out. An arm stretcher, this bike was not.

The motor had an incredibly narrow powerband and was nearly impossible to keep on the pipe as well. It was gutless off the line and only moderately perky in the middle. Top-end power was utterly non-existent and the bike only got slower the harder you wrung it out. Keeping the Why-Zed in this narrow sweet spot was all but impossible and the only immensely talented riders had any hope of keeping it at full boil without running out of steam or soliciting a bog. When you added in its reluctant transmission your mission was hopeless.

Even worse for the hapless YZ125 pilot, the motor defied improvement. Many dollars were wasted by dads trying to get some sort of performance out of the hapless machine. Mods were plentiful, but actually improving the bike’s performance proved elusive. Often, all the changes did was move the power around slightly and decrease the machine’s reliability.

If the YZ had been blessed with a rocket motor most of its other problems might have been overlooked. Unlike the 250 or 500 class where handling is as important as power, the 125 class is all about one thing, horsepower. Without a stellar power plant to fall back on the YZ’s other shortcomings became even more glaring.

Pretty, but painfully slow, the 1985 YZ125 was the low-point for Yamaha decade of up-and-down 125 performance. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Because horsepower can wreak havoc on the handling of a motorcycle (see the 1984 CR500R above) slow bikes are typically good handlers. The 1985 YZ125 was the exception to that rule. The ’85 YZ’s chassis was just a confused mess. The bikes had pronounced understeer and would push the front end badly in flat turns. If by some miracle you could get the YZ up to speed it would dance all over the track trying to eject you into the cheap seats. The YZ’s forks were way too soft and under sprung for anyone over eighty pounds, resulting in a metal-to-metal clank over any decent-sized jump. If you added oil to fight bottoming then they would become harsh and pound your hands to putty. The only real fix was to go with stiffer springs and install a Simons Anti-Cavitation kit in the forks. If you left them stock, your wrists were doomed to be pummeled on every bump.

The shock on the YZ was slightly better than the forks. This was the year Yamaha came up with their wacky BASS set up and stuck it on all the full-size YZs. The BASS or Brake Actuated Suspension System was in theory supposed to make the bike perform better in braking bumps. The idea was that when you pressed the rear brake a little cable would tell the shock to back off the compression damping resulting in less kicking under braking. In reality the system was more effective at causing the shock to bottom when you least expected it. Most people just disconnected it altogether.

Once you tossed the BASS the shock still had problems. Like the forks, it was set up too soft and it would bottom out if pushed. Much worse was its affinity for “Yama-hop” as it was known back in the day. Yamaha’s from this era had a real problem with sudden sharp whoops or holes. If you made the mistake of backing off the throttle even a bit, the shock would rebound suddenly and kick from side to side. Some times it would kick hard enough to literally kick your feet off the pegs. The problem was much worse on the bigger YZ’s but the little 125 was not immune to the dreaded “hop”. Much like the forks, the only sure fire way to fix the shock was to ditch it completely and put on an Ohlins (of course at which point you would still be left with a very expensive, well suspended, pathetically slow, unreliable POS, but who’s counting).

Thankfully for Yamaha fans everywhere, the 1986 YZ125 was a huge improvement over the Yama-dog ’85. The 86 YZ was still no match for the world-beating ’86 CR125R but at least it was no longer an embarrassment. For Yamaha in 1986 that was a major accomplishment.

Matthes did a Tell Us a Story on this bike as his brother and dad were also caught in the vortex of horribleness that was the YZ125 HERE

If looks won races the 1998 Honda CR125R would have been an all-star. Photo Credit: Honda

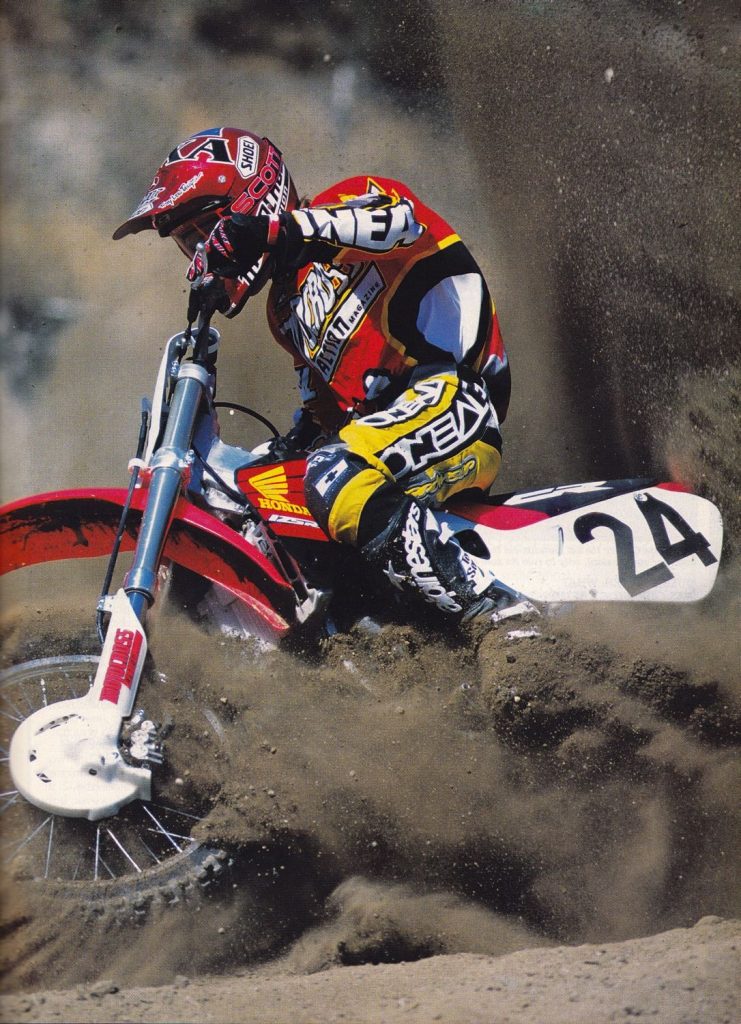

8 – The 1998 Honda CR125R

What we have here is the bike that killed the CR125R. The patient took another decade to finally be put out of its misery, but make no mistake; the fatal wound was delivered in the fall of 1997. Up until that point the Honda CR125R had enjoyed over a decade of stellar success on and off the track. The little red rockets had claimed nine out of thirteen National 125 Motocross titles and the lion’s share of 125 sales. Some years, there had been easier to ride 125s, but year in and year out, there was no faster bike than Honda’s CR125R. All that changed in the fall of ’97. The 1998 CR125R was the end of a dynasty.

The previous year, Honda had made the bold move to ditch their successful and proven CR250R chassis and go with a road race-inspired twin-spar aluminum frame. The bike had been a huge sales success but a critical failure. Once customers got past the Buck Rodgers looks, they had quickly realized the ’97 CR250R had major problems (I was close to actually putting this jewel on the list but the 250 still had that sweet motor so in the end, the 125 won. Or is that lost…). For 1998 the CR125R got to be the next victim of the aluminum revolution.

In fairness, the 1997 CR125R had been getting a little long in the tooth at this point and was about due for a refresh. The once omnipotent motor had been finally eclipsed by the…wait for it…Yamaha YZ125 (will miracles never cease?). The one-time toad of the 125 class had been turned into a handsome prince, laying the smackdown on its 125 rivals in ’96 and ’97. In 1998 the CR125R’s motor was an eight-year-old design, which had made its debut on the 1990 CR125R. The little HPP (Honda Power Port) motor’s roots actually stretched back even further to the original 1986 CR250R where the HPP design had made its debut. The HPP equipped CR125s had always been top-end screamers, pulling to the moon with an ear-splitting shriek. While their top-end pull had never been equaled, they were difficult motors to go fast on, requiring a skilled pilot to get the most out of them. In 1996, Yamaha had stolen Honda’s thunder by producing a 125 with a 250’s powerband. The ’96 and ’97 YZ125’s were little torque monsters for 125s, with much easier to use motors than the one-dimensional Honda. For 1998, Honda pulled out all the stops, launching an all-new CR125R in hopes of taking down the class-leading Yamaha.

What’s black and red and slow all over? Photo Credit: Motocross Action

There is no denying the curb appeal of the 1998 CR125R. That huge aluminum frame and futuristic bodywork looked a decade ahead of the competition in 1998. On the showroom floor, it was a winner, but on the track, it left a lot to be desired. Just like its big brother, the CR125R’s chassis was way overbuilt. The first generation frame had been designed more for durability than comfort, and as a result, funneled every bump straight to the rider. These bikes were tinglers too, passing on every ounce of vibration straight through frame right to your hands. The all-new CR chassis had a nasty push in the front end making it hard to hit the inside line. The one good thing about the ultra-strong frame was that it did track straight through the whoops. However, the frame gave the bike a dead feeling, thudding through bumps a YZ or RM would float over. The suspension on the CR was marginal at best and just not up to the task of taming the unforgiving frame. Between the pounding from the suspension and the hand numbing vibration from the frame, the little CR was way more tiring to ride than its 125 competition.

Perhaps the worst consequence of the new chassis was what it did to the once fire breathing engine. It seemed that somewhere in the transition to the new frame the little Honda lost its mojo. Honda had gone in search of broader power for the 98 CR but came back with a motor better suited to a moped. The new-look CR had very old look power with motor performance closer to an 85 YZ than a 98 one. The motor was sluggish off the bottom and only made decent power in the midrange. If you tried to rev it out like every CR125 made since the Carter administration, it would only make noise and go slower. The motor was badly choked off and required multiple stabs of the clutch to get it to pull onto its razor-thin powerband. The frame itself may have been to blame for the missing top end as the large frame spars required a redesign of the CR’s intake tract. The new intake design did not flow as well as the old one and some have speculated that this was the reason for the choked off performance. The poor CR motor was further handicapped by the use of a five-speed gearbox. I have no idea what Honda was thinking with this brilliant move but it virtually guaranteed you were always in the wrong gear, every time, all the time. The last thing a bike with such a limited power spread needed was one less gear in the transmission. Unfortunately for Honda, the end result of all this design brilliance was a 125 that couldn’t outrun their own CR85R minibike, much less a YZ125. When you combine the punishing ride with the anemic power plant you have the recipe for the number eight debacle on our list.

The 1998 Honda CR125R was the end of an era in 125 racing. After 1998, Honda would never again produce a class-leading 125. Although the CR125R would see two more complete redesigns, Honda was never again able to recapture the magic that had taken them to so many 125 titles. The later CR’s fixed most of the problems with the aluminum chassis but none of them ever found the lost horsepower. Honda finally killed the CR125R in 2007, deciding to put all its resources into four-strokes. The once-mighty CR125R had finally been vanquished for good.

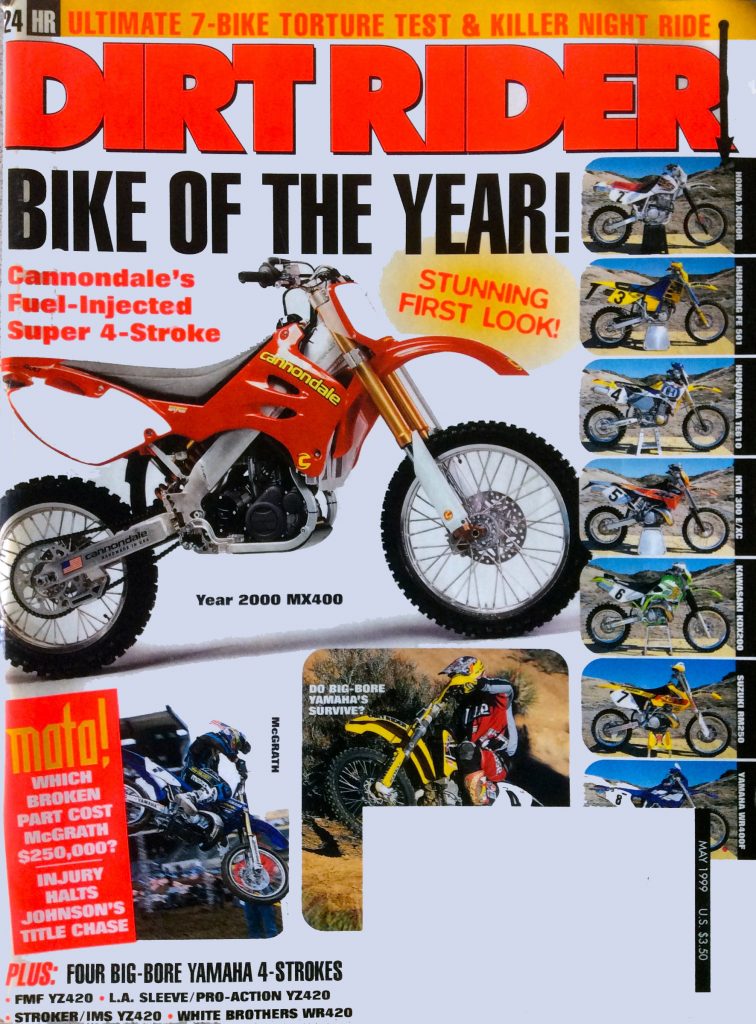

Dirt Rider magazine proclaimed Cannondale’s new four-stroke the “1999 Bike of the Year” well before any testers had actually ridden it. It was a level of hype that the Cannondale could never live up to. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

9 – The 2001 Cannondale MX400

It was an ambitious plan; to produce a motocross bike designed and built right here in the good old USA. It started out with lofty goals and endless optimism, but in the end, too many mistakes were made and the great American experiment took down the company that had given it life. As the proverb says, “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions.” That pretty much sums up the Cannondale motocross story.

Joe Montgomery, Jim Catrambone, and Ron Davis founded the Cannondale Company in the town of Bethel, Connecticut in 1971. Originally they manufactured camping equipment and bicycle accessories, building up a loyal following throughout the seventies. In 1983, they branched out into making their own bicycles and over the next fifteen years became a huge success in the cycling world, specializing in cutting edge aluminum-framed bikes for on and off-road cycling. In 1998, Cannondale made the bold decision to go where so many had gone before and failed, and decided to take on the challenge of producing their own motocross-racing machine. Intending to leverage their extensive experience in aluminum frame production and design, they took on the daunting task of crafting and building an all-new motorcycle to take on the established Japanese brands. Cannondale intended to use bold, new “out of the box” thinking in their designs to set them apart from their competition. While incredibly innovative, these bold choices in the design would end up dooming the ambitious Cannondale motocross project.

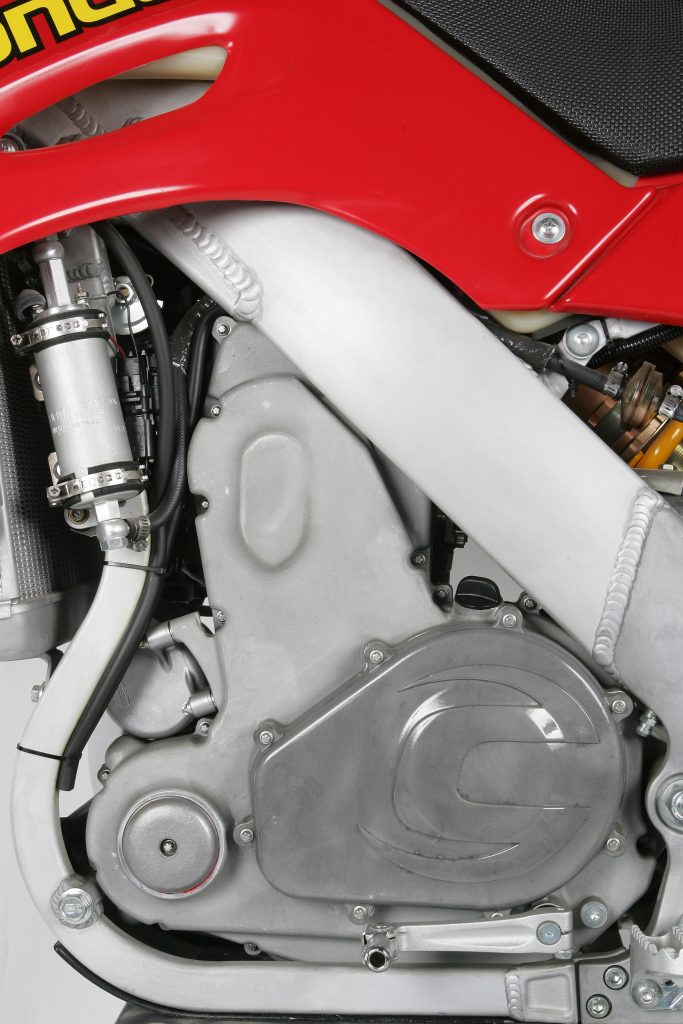

The production Cannondale was incredibly innovative offering features like a reverse-motor design, alloy chassis, electric start, and fuel injection long before they were commonplace on a motocross machine. Photo Credit Cannondale

The Cannondale motorcycle project was fraught with difficulties from the very beginning. In their pursuit to be forward-thinking, Cannondale had taken a huge gamble by using a radically different motor design for their new motorcycle. The Cannondale was going to use a reversed cylinder design with the intake at the front and the exhaust outlet in the back. Another radical departure was the decision to use fuel injection and electric starting on the motor (this was a full decade before those features would make their way on to the motorcycles of the “Big Five”). On paper, there seemed to be solid reasons for using this radical design. You could have a better flowing intake by mounting the airbox in front of the motorcycle and with the exhaust exiting straight out the back, you had less pipe routing to worry about. Unfortunately, once Cannondale actually started testing their new engine it became obvious the design created a multitude of all new engineering challenges.

The first problem was the innovative “ram-air” airbox behind the front number plate. It was just not up to the job of getting enough air to the 400cc mill. A motor is little more than an air pump at its core and if you can’t get that air in and out efficiently you will never get decent power out of it. Cannondale ended up having to add a second air filter under the tank to feed the starving motor. This meant you had to virtually disassemble the whole bike whenever you went to clean the filters on your Cannondale (god knows we all love to clean air filters).

The short, rear-exit exhaust pipe led to performance issues of its own as the pipe was too short to properly tune the power output (this is why Yamaha’s similar backward motor uses such a long, coiled “tornado” head pipe). This overly short head pipe contributed mightily to the Cannondale’s short, shallow power delivery. The bold move to go with fuel injection had also brought with it a slew of new tuning issues to be worked out. By making so many radical departures from conventional design, Cannondale made their new motorcycle project exponentially more difficult.

While incredibly innovative, the decision to blaze so many new trails in motor design badly taxed the cash-strapped and time-crunched Cannondale design team. Photo Credit: Stephane Legrand

The one area Cannondale felt they had a handle on things was in the frame. Aluminum frames were their specialty and here they would no doubt have an advantage. Unfortunately, Cannondale decided to use the unloved ’97-’99 Honda CR aluminum frames as their inspiration. The Cannondale chassis bore more than a passing resemblance to the original Honda design and suffered many of its same maladies. By the time the Cannondale actually made its debut, this comparison did not work in the machine’s favor.

The 2001 MX400 was really still a work in progress when it finally hit the showroom floors in the fall of 2000. Under massive pressure to produce anything, Cannondale rushed the production on their all-new race bike. Once people actually started to ride the bikes, it became very obvious that the MX400 was not yet ready for prime time.

Before you even actually rode the bike you could tell it was a very different sort of motorcycle. One side of the motor was completely smooth with none of the usual nooks and crannies one associates with a dirt bike engine. The other side was a mass of hoses and wires that looked like something a high school kid threw together in his back yard. Once you got past the odd appearance of the motor you would be struck by the sheer mass of it. The lower section of the motor jutted forward and appeared to be just looking for some dirt to plow into. With that massive motor hanging way down beneath the bike, the Cannondale looked closer in size to an XR650R than a CR250R. One heave off the stand was enough to prove the similarity was more than skin deep.

There were high hopes for the first legitimate made in America machine since the heyday of ATK in the 1980s. Unfortunately, Cannondale’s early struggles would prevent it from becoming the major motocross player so many patriotic racers had hoped for. Photo Credit: Stephane Legrand

For a motocross machine, the MX400 was hopelessly overweight. Tipping the scales at over 260lbs the bike was a good 15lbs heavier than the class-leading, but also seriously porky, YZ426F. That made it 40lbs heavier than a CR250R two-stroke. Unlike some heavy bikes that hide their weight once in motion, the Cannondale felt even heavier than its 260lbs once on the track. Cannondale had spec’d premium Ohlins suspension components on the MX400 but they were poorly set up. The forks were way too soft for the Cannondale’s substantial girth. The shock was too soft initially then too stiff towards the end of the travel. It would sit too low in the suspension’s stroke and bang and clunk all the way around the track. The suspension handicapped the handling slightly but even if you stiffened it up sufficiently the bike still handled like the big truck that it was. The MX400 tracked strait and true at speed but was reluctant to change direction. In short, the Cannondale was no RM125 but it was a decent handling bike in serious need of a diet.

The Cannondale was well ahead of its time with innovations like electric starting and fuel injection. Photo Credit: Stephane Legrand

Predictably, the real problems for the Cannondale were in the motor department. Just starting the bike was a hit-or-miss affair. The MX400 was equipped with an electric starter but it was barely up to the job of starting the beast. It worked pretty well when cold but gave up the ghost when the bike got hot (there was no kickstart backup by the way, so you would be stranded till you found a hill to bump-start it on). In terms of performance, the MX400 was well below the output of machines like the KTM 520 and YZ426F. The overall output was on par with a typical 250 two-stroke of the time, but the Cannondale was saddled with 40-pounds more weight. The motor was also difficult to live with at times with its buggy fuel injection offering erratic performance and poor low-end response. Even though the machine was fuel-injected, it also suffered from the dreaded hiccup-and die syndrome that most carburated four-strokes were notorious for.

|

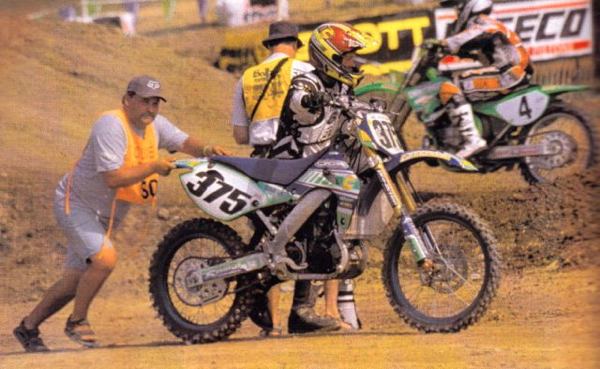

| More often than not this was the view people got of the fragile MX400. |

The early Cannondales also had serious problems with reliability. Virtually every test bike given to the magazines broke down in one way or another. MXA blew up theirs twice in the first week of testing. That was not the kind of PR a new motorcycle company needs. Maybe even worse was Cannondale’s record on the track as test riders Keith Johnson and Jeff Gibson struggled to just finish races on the fragile machines. Pictures of Cannondales being pushed off the side of the track became commonplace in 2000. Even as the bikes were going into production, Cannondale was still testing and modifying components on the machines. Unfortunately, the buying the public was basically a bunch of guinea pigs as Cannondale tried to work out the bugs. Needless to say, it did not take long for word to get out about Cannondale’s myriad of issues.

Cannondale did everything it could to address the many problems that plagued the first year bike, but its reputation had already been irreparably damaged. In 2002 Cannondale broadened their model line to include ATV and off-road models to go with the MX400. The ATVs, in particular, were extremely well received but the stigma of poor reliability never completely left the brand. The red ink eventually got the better of the cycling giant and in 2003 Cannondale Motorcycles filed for bankruptcy protection, eventually selling off the motorcycle division. Thus ended the great American motocross experiment, a sad case of what might have been.

On paper, the Kawasaki/Suzuki alliance looked like a smart usage of resources but territorial squabbling and corporate compromises would lead to one of the most disappointing motocross machines of all time. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

10 – The 2004 Kawasaki KXF250/ Suzuki RM-Z250

In the early 2000s, Kawasaki and Suzuki made a decision to commit to a strategic alliance. The two manufacturers would pool their resources to develop some joint models to help them better compete with perennial powers, Honda and Yamaha. Along with the new models to be developed, they would allow some of each other’s models to be sold by the other with the addition of new plastic and graphics. The first product from this alliance was the hotly anticipated 2004 RM-Z/KX-F 250 four-strokes.

The 2004 season was a good one for four-stroke aficionados. After having three years all to itself, the revolutionary YZ250F finally had some competition in 2004. Along with the new 250 four-strokes from Kawasaki and Suzuki, Honda also threw its hat into the ring with its all-new CRF250R. The 2004 battle for 250 four-stroke supremacy looked to be a good one.

One look at the new KXF and RMZ made it very apparent the two bikes were virtually identical. The only real differences between the two were the color and shape of the radiator shrouds. Other than those small differences, they were basically the same machine. A machine that turned out to be an odd combination of both manufacturers that satisfied neither.

At least they were pretty… Photo Credit: Kawasaki and Suzuki

The development of the 2004 RM-Z and KX-F ended up being a joint venture with each company having a hand in its final design. The motor was designed by Suzuki but actually built by Kawasaki. The chassis and the rest of the machine were 100% Kawasaki in design and execution. That meant the bike handled and felt like a KX instead of an RM. Unfortunalty, this meant that if you bought the all-new RM-Z thinking it was going to turn like your RM125, you were in for a rude awakening. The new machine handled much closer to a KX than any Suzuki, which meant it was stable at speed but less willing to grab the inside line. This was not necessarily a bad thing, but it was definitely not what you expected from a bike with a big Suzuki “S” on the shroud.

The suspension on the twins was passible but not perfect. The Kawazuki had an overly soft fork coupled with a stiff rear shock. That gave the bike a jacked-up rear end stance that made the bike feel unbalanced. You could slide the forks down in the clamps to try and even it out, but it would still stinkbug around the track. The best fix was to swap out the bottom link for an aftermarket alternative from a company like Pro Circuit. If you made that change the stance was evened out and the shock provided smoother action. Overall, the chassis was a decent handler as long as you did not expect it to feel like an RM.

With the RM-Z and KX-F, the real problems were elsewhere. Like so many other machines on this list, the wonder twins’ real issues were in the engine bay. The Suzuki designed motor was very different in character than the offerings from Honda and Yamaha at the time. Where those motors were all about revving to the moon, the Kawazuki motor was a torquer. The machines preferred to be lugged rather than revved and ran much more like a small 450 than a big 125. This was not necessarily a bad thing as the motors did produce decent power in their own way. Novices and vets loved it, but pros found it wanting. Unfortunately, much like our number nine Cannondale, the real problem with the thumper twins was reliability. Put frankly, both of them had a really hard time staying in one piece.

For starters, the bikes ran terribly hot. They would start boiling coolant after only a few minutes if ridden slowly and overheat regularly. Woe be to you if you forgot to check your coolant before every ride. Then there was the little issue of oil capacity. Unlike the YZ250F, the Kawazukis did not feature an external oil tank. This limited their overall oil capacity, made cooling more difficult, and necessitated a constant checking oil of the level. Because of this reduced capacity, oil consumption became a major concern on the two machines (and Honda’s new CRF250R as well). This oil consumption issue became a real problem as the little four-bangers loved to drink the stuff. If you forgot to check your oil before every ride there was a good chance you might be in for a very expensive surprise.

In another brilliant move, Suzuki pulled perhaps the stupidest bit of cost-cutting ever by making the oil filter cover one piece with the water pump. This meant if you wanted to change the oil you had to drain the coolant first (maybe they figured it would burn so much oil you could just keep adding fresh? Hey, it worked on my ’78 Ford Pinto). In a bike where oil life is CRITICAL, making the task a complete pain in the neck was not smart. Some of the bike’s many engine failures might be attributed to four-stroke newbies just letting the oil change interval go too far. Pro Circuit made even more money by selling water pump covers to fix this glaring problem (I sense a pattern here).

Along with the overheating and oil consumption issues, there were problems with the cam buckets, valves, and valve seats (once again Pro Circuit to the rescue). If none of those things failed, then you still had a good chance of the transmission letting go. Race teams spent astronomical sums of money trying to work out the many issues these bikes had. Unfortunately, as they squeezed more and more power out of the machines the reliability continued to suffer, leading to several well-publicized DNF’s during the ’04-’05 seasons.

The Kawasaki/Suzuki alliance would only last a few years, with Kawasaki introduccing a all-new 100% green version in 2006. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

As problems mounted and fingers pointed, Suzuki and Kawasaki began to sour on their new friendship. Kawasaki was not happy with the terrible reliability of the Suzuki designed motor and Suzuki was not happy with the poor handling of the Kawasaki chassis. In the end, they decided to get a divorce and take their 250F development in separate directions. In 2006 Kawasaki came out with an all-new 250F and it was light years better than the machine it replaced. Suzuki would have to soldier on with the old design for another year (much to their support team’s chagrin) before finally introducing a 100% Suzuki 250F in 2007. The Kawasaki’Suzuki alliance ended up going down as a failure and the bike it produced will always be remembered as the bastard child of that failed marriage.