This week’s selection from Greg Primm’s Classic Steel is Yamaha’s first liquid-cooled 250cc motocrosser, the 1982 YZ250J.

By: Tony Blazier

The 1982 YZ250J was a radical departure from all of Yamaha’s previous 250s. Everything from the up-the-tank safety seat to the small looking liquid cooled cylinder told you this was no rehashed seventies machine. Photo Credit: Yamaha

For 1982, Yamaha introduced an all-new YZ250 for the first time in several years. The YZ250J was a complete redesign and featured the very latest in motocross technology. The ’82 model year would see the introduction of Yamaha’s new “power valve” system and the addition of liquid cooling for the first time. In addition to the new motor, the ’82 YZ250 would feature an all-new chassis design and a radically altered Monocross rear suspension system. Even the bodywork and graphics were all-new for ’82. On paper, the new YZ looked like a world beater. In reality, it turned out to be a colossal disappointment.

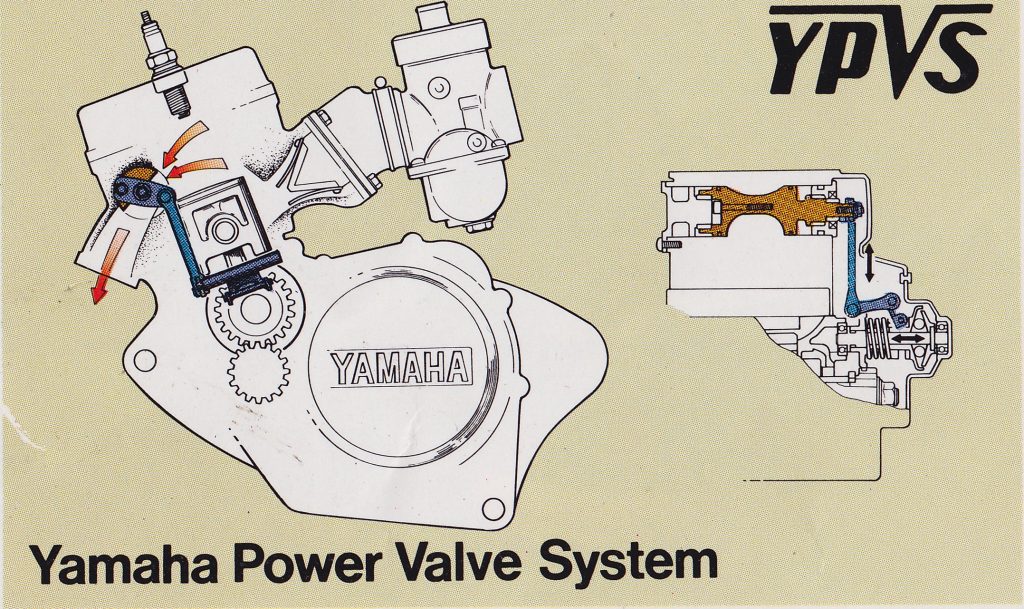

In 1982, Yamaha introduced the world to the concept of the “power valve.” Dubbed the Yamaha Power Valve System (YPVS), this new mechanism used a rotating drum to vary the height of the exhaust port based on motor rpm. By altering port timing, the YPVS allowed the engineers to tune the bike for better power, over a broader range. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1982, Yamaha introduced the world to the concept of the “power valve.” Dubbed the Yamaha Power Valve System (YPVS), this new mechanism used a rotating drum to vary the height of the exhaust port based on motor rpm. By altering port timing, the YPVS allowed the engineers to tune the bike for better power, over a broader range. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1982, the new YZ250 motor was at the very cutting edge of two-stroke technology. The new power valve technology that Yamaha was introducing on the ’82 YZ had been used for a few years on their works racers, but it had never been offered to regular consumers. Christened the “Yamaha Power Valve System” (YPVS) by the marketing department; the new exhaust port mechanism was designed to broaden the powerband by altering the exhaust port timing to based on engine rpm. To do this, it utilized a small rotating drum connected to a centrifugal-ball governor. As engine rpm climbed, small ball bearings in the governor were forced outward, engaging the mechanism and rotating the drum to uncover more of the exhaust port opening. In theory, this allowed the engineers to have two different porting profiles in the same motor. One for torque. and one for high-rpm power.

Yamaha would continue to use this original YPVS design on the YZ250 for over a decade. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Complementing the YPVS was Yamaha’s all-new liquid cooling system. Believe it or not, in 1982, many people actually thought it was unnecessary to use liquid-cooling on a 250cc machine. Critics believed the benefits of liquid-cooling were just not justified when weighed against its potential detriments. The added cost, complexity, and weight of the hardware was just not going to be offset enough any potential performance gains. In their eyes, simpler was better.

All-new from the ground up, the 1982 YZ250J featured Yamaha’s first usage of a rear suspension linkage and liquid cooling. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Yamaha’s unique take on liquid cooling mounted the radiator on the upper triple clamps and piped the coolant through the frame. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand.

Yamaha’s unique take on liquid cooling mounted the radiator on the upper triple clamps and piped the coolant through the frame. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand.

It would take a few years for Yamaha to make full use of the potential in their new YPVS motor design. The ’82 YZ power plant proved torquey, but not particularly powerful. Low-end thrust was strong, but there was not much left after that initial burst. High-tech or not, the ’82 YZ offered the least potent mill in the 250 class of 1982. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

It would take a few years for Yamaha to make full use of the potential in their new YPVS motor design. The ’82 YZ power plant proved torquey, but not particularly powerful. Low-end thrust was strong, but there was not much left after that initial burst. High-tech or not, the ’82 YZ offered the least potent mill in the 250 class of 1982. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

For all its techno trickery, the ’82 YZ250 turned out to actually be at the back of the pack in performance. The YPVS motor did indeed have the excellent low-end power expected from the new power-valve system, but after that surge, the fun was over. Midrange and top-end power were lackluster at best and with very little pull past the lower end of the curve. Revving it out actually made it go slower and the best way to go fast was to keep it a gear high and try not to let it rev past the sweet spot.

The new YZ250 looked impressive on the page but turned out to be a paper tiger on the track. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In spite of its high-tech internals, the ultra-modern YZ power plant actually ended up getting smoked by all of its rivals, It even got left behind by Kawasaki’s decidedly low-tech air-cooled KX250 motor. Technology like the power valve was indeed the future, but Yamaha’s first attempt did very little to show its true potential.

The highly-place single radiator in the YZ250 was covered by this uniquely styled and vented number plate. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The highly-place single radiator in the YZ250 was covered by this uniquely styled and vented number plate. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Like the motor, Yamaha’s new liquid-cooling system suffered from a few teething problems. In 1982, none of the manufactures had yet figured out the ideal place to mount the radiator on the bike. Each brand had a slightly different take on what was best and tried several variations in an attempt to balance handling, reliability, and performance.

Another innovation on the 1982 YZs was the use of an up-the-tank- safety seat for the first time. Your nuts thank you. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In Yamaha’s case, they had decided to go with a single radiator mounted up high on the chassis. By mounting it in front of the steering head, it was thought it would be less vulnerable to crash damage and able to receive the maximum amount of cooling air. Unfortunately, however, this led to several issues for the engineers.

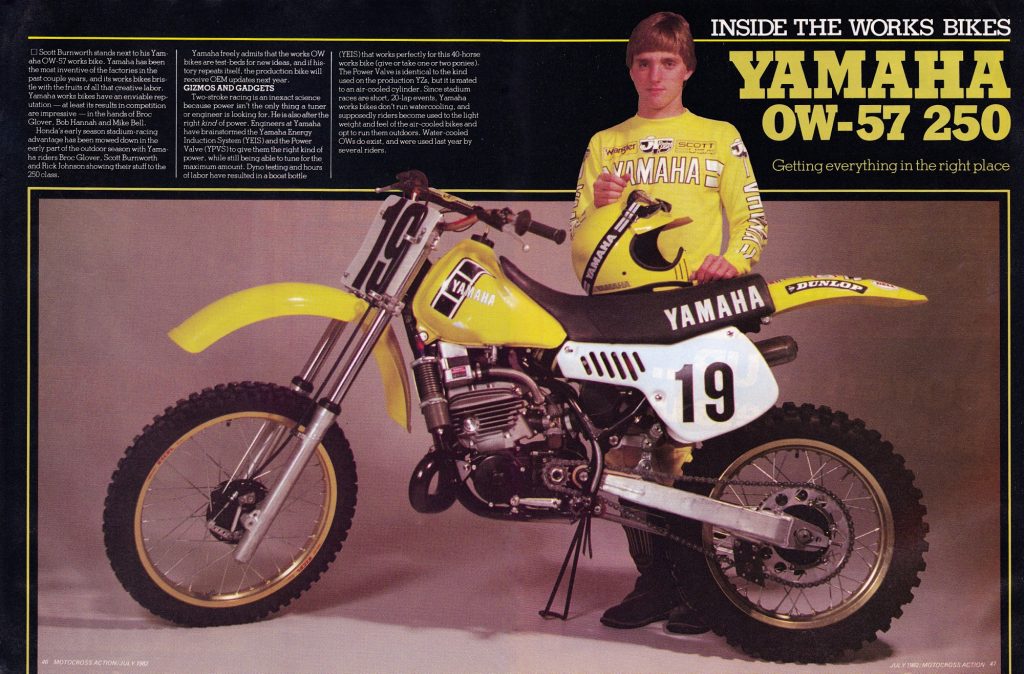

In 1982, Yamaha factory riders like Scott Burnworth disliked the handling of the new YZ so much that they went back to air-cooling for their works bikes. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The first problem was complexity, as Yamaha had to figure out a way to get the coolant from the radiator to the motor, while still allowing the rider to steer the bike. Their solution was to run the coolant hose inside the steering stem and then pipe it down the frame. Predictably, this led to leaks.

The other problem with this design was that it adversely affected the handling of the bike. The decision to place the radiator and all its hardware on the triple clamps meant that there was a lot of weight very high-up on the chassis. This made the steering of the bike feel sluggish and added to a very top-heavy feel that no one liked. The system was so poorly designed that Yamaha’s factory team in ’82 actually went back to air-cooled motors on their race bikes.

Bob Hannah absolutely hated these early-eighties YZs. He complained that they were falling behind the competition and railed to executives about the handling of their machines. At the end of ’82, Bob decided he had had enough and bailed on his Yamaha contact so he could move over to take Donnie Hansen’s (Donnie suffered a career-ending injury while practicing for the Motocross des Nations at the end of ’82) place on the powerful factory Honda squad. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Bob Hannah absolutely hated these early-eighties YZs. He complained that they were falling behind the competition and railed to executives about the handling of their machines. At the end of ’82, Bob decided he had had enough and bailed on his Yamaha contact so he could move over to take Donnie Hansen’s (Donnie suffered a career-ending injury while practicing for the Motocross des Nations at the end of ’82) place on the powerful factory Honda squad. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The chassis on the ’82 YZ250 featured Yamaha’s first major redesign of their Mono-X rear suspension system since its introduction in the mid-seventies. In an attempt to keep up with Suzuki’s class-leading Full-Floater suspension, Yamaha ditched their original monoshock design and introduced a hybrid system that combined the original monoshock with a new rising-rate linkage. The shock was still mounted up high and under the seat, as it had been for years, but now there was a bellcrank and pull-rod placed between the shock and swingarm.

Here is a good look at the ’82 YZ’s new Mono-X rear linkage. The new rear end retained the previous design’s shock location, but now it attached to a rising-rate set of linkage arms. The ‘82 design suffered from a high center of gravity and mediocre performance. For ’83 Yamaha would ditch this design altogether and go with a setup much closer to what we use today. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Performance of the new shock design turned out to be mediocre at best. In spite of offering adjustments for compression, rebound, and spring preload, it was all but impossible to find a setting that provided decent ride comfort without crashing to the stops on hard hits. Even for a novice, the stock settings were likely to be too soft.

Yamaha’s new Mono-X rear suspension proved far less effective at taming the track than the rears of its competitors. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Up front, the new YZ featured a set of beefy 43mm Kayaba forks. The forks lacked damping adjustments but could be tuned by adjusting the oil level and adding or subtracting air pressure. Overall travel was a standard-for-the-time 11-inches.

These Kayaba forks were state-of-the-art in ’82. The 43mm sliders were strong and flex-free (by standards of the time), but offered very little tune-ability. Compression and rebound damping were fixed, with no external adjustment available. Adding or subtracting air pressure and adjusting oil level were the only way to fine-tune their performance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In terms of performance, the YZ’s 43mm forks were a bit of a disappointment in ’82. They were flex-free and sturdy, but softly sprung and underdamped. At trail speeds, they worked well enough, but once you picked up the pace, they quickly reached the limits of their potential. A decent-sized whoop would eat up most of the travel and any Hannah-esque leaps would be met with a metal-to-metal clank. In truth, none of the forks available in 1982 were particularly great, but even by those standards, the YZ’s fork performance was poor.

Big Boy: At 240-pounds, 1982 Yamaha YZ250 two-stroke weighed in at a staggering 20-pounds more than a modern KTM four-stroke. With its prodigious weigh, poor weight distribution and marshmallow suspension, getting the YZ off the ground was an ill-advised proposition in 1982. Photo Credit: Cycle World

The handling of the YZ was even worse than the suspension in 1982, The bike was seriously overweight, tipping the scales at over 240 pounds. That was a whopping 22-pounds more than the ’81 YZ250. That weight could be felt on the track and the high placement of the cooling system made that sensation even worse. The geometry was also slightly odd, and the bike felt as if the two ends of the bike had different ideas about what they wanted to do. Coming into turns, the heavy front end liked to flop over and execute a course change, but the rest of the chassis felt as if it wanted to keep plowing forward. The bike’s prodigious weigh, poor weight distribution and marshmallow suspension only made this disjointed feel worse. In the end, the best way to get the porky YZ to turn was to stay away from the over-burdened front and try to change direction by sliding the rear around Villopoto-style.

Dual leading shoe brakes like this one were as good as the drum was ever going to get. They were far superior to the single leading shoe brakes of the seventies, but a far cry from the discs we use today. Even a dual leading shoe brake like this would require the use of all four fingers to bring a bike down from speed. Amazingly, Dirt Bike commented that they did not know how anyone could need more brake than this in ’82. Now, this brake would feel underpowered on a 50cc mini bike. My, how times change. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Dual leading shoe brakes like this one were as good as the drum was ever going to get. They were far superior to the single leading shoe brakes of the seventies, but a far cry from the discs we use today. Even a dual leading shoe brake like this would require the use of all four fingers to bring a bike down from speed. Amazingly, Dirt Bike commented that they did not know how anyone could need more brake than this in ’82. Now, this brake would feel underpowered on a 50cc mini bike. My, how times change. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Big, heavy, slow and ill-handling, the 1982 YZ250J proved to be an impressive technical exercise, but a disappointing racer. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The groundbreaking ’82 YZ250 ended up being a major disappointment for Yamaha. As a showcase for innovative designs, it was impressive. But as a race bike, it was a dud. The acronyms, doo-dads, and gizmos looked great in magazine ads, but on the track, they proved of dubious benefit. In the end, the 1982 YZ250J turned out to be an impressive technical exercise, but little else.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram – @TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com