For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at KTM’s controversial 2003 250SX.

By: Tony Blazier

|

| Although it looked very similar to the 2002 model, the 2003 250SX was an all-new machine. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

In the early 2000s, KTM was making a major push for respectability here in the States. They started by bringing over 125 World Champion Grant Langston from Europe to race here in the US. Grant immediately rewarded the Austrian brand with race wins and credibility. Their 125 was rocket-fast capable of beating the best from Japan with a talented rider aboard. In his first season here, Langston piloted his KTM to five race wins and nearly the 125 National Motocross title. Only a broken wheel at the series finale kept the charismatic South African from bringing KTM the championship in his first attempt.

|

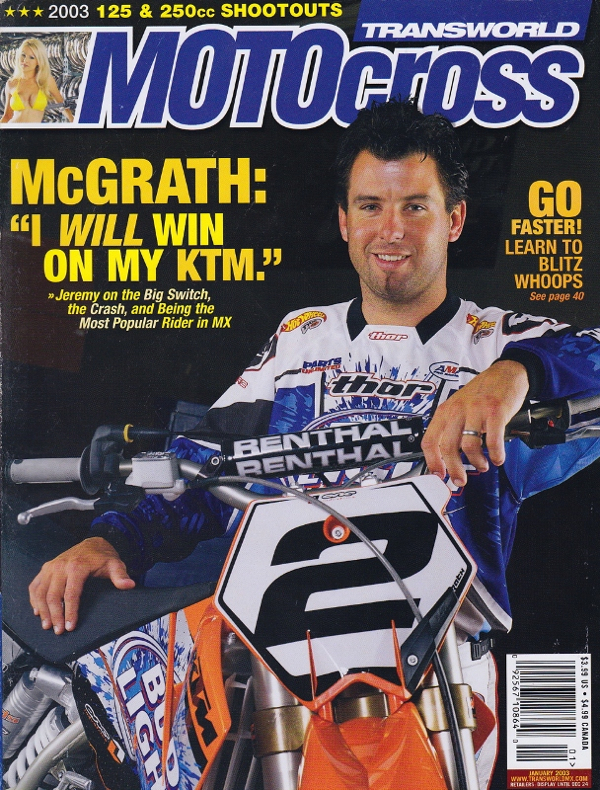

| KTM made a lot of promises to Jeremy McGrath before he signed with the team for 2003. They were supposed to deliver an all-new linkage-equipped works bike for him to race and that would improve the Austrian bike’s notoriously wayward handling. As it turned out, the promised bike never materialized, and MC was never able to back up his Transworld cover boast. |

After two-year in the 125 class, Langston was looking to move up to the 250 division for 2003. At this point, Langston was quite accomplished at motocross, but still a bit rough around the edges at supercross. The new 250 was also an unproven machine that had not comported itself well inside the stadiums. Outdoors and off-road, the KTM’s no-link PDS suspension seemed to work well, but under the lights, its unique handling proved difficult to tame. For KTM, the best situation would be to bring in a more experienced rider to help develop the 250 program and mentor Langston. Amazingly, that is just what happened in the fall of 2002 when the greatest supercross rider in history basically fell into their laps.

The Jeremy McGrath Bud Light KTM experiment ended before it could really get started. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The Jeremy McGrath Bud Light KTM experiment ended before it could really get started. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

In 2002, Jeremy McGrath endured the worst season of his 250 professional career. After dominating for nearly a decade, he was forced to play second-fiddle to Honda’s newest hire, Ricky Carmicheal. At the end of the year, a contract dispute with Yamaha left the seven-time champ looking for a new home. That new home would turn out to be KTM.

The KTM/ McGrath deal was a PR nightmare from start to finish. It made the Austrian brand look terrible and stirred up a lot of hard feelings on both sides. Even fellow KTM rider Grant Langston jumped into the fray, taking cheap shots at McGrath over the breakup. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

For KTM, the McGrath hire looked like a major coup. It offered a fresh start for McGrath and a huge publicity windfall for KTM. Unfortunately, however, that PR dream quickly turned into a bad press nightmare. Before the start of the season, McGrath suffered some nasty crashes that shook his confidence in the new machine. A promised new bike with a rear-linkage never materialized and McGrath bailed on the contract before the season even began. Because of this debacle, the 2003 KTM 250SX has gone down to history as the bike that ended the career of the greatest Supercross racer of all time.

|

| The case-reed KTM mill pumped out an eye-opening 49HP in stock trim. With a Pro Circuit “McGrath” pipe that number climbed into the low 50s. No other 250 even came close to the KTM’s massive power output in 2003. It was one of the few 250s that could actually run with the new 450cc four-strokes straight-up. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

Despite its reputation, 2003 KTM 250SX was not a completely hopeless motorcycle. In point of fact, the KTM 250SX was actually the fastest bike on the track. In 2003, the Austrians had not yet figured out to make a bike handle, but they had a firm grasp on horsepower. Like an American muscle car of old, the 2003 KTM 250SX was a wickedly-fast brute, with an utter lack of finesse.

|

| With Bud Light pulling out of the sponsorship deal after McGrath’s retirement, these One Industries replica graphics quickly became sought-after collector’s items. |

In stock condition, the ‘03 250SX produced a very broad spread of power. The ’02 model had possessed a violent low-to-mid hit that was a real handful, but the ’03 model spread that burst out over a broader range. In order to accomplish this, KTM’s engineers re-tuned the power valve, added weight to the crankshaft and raised the gearing. This resulted in a motor that was still brutally fast but more easily managed. The motor hooked up easier, revved slower, and offered a less-abrupt feel. Some riders missed the 2002’s barky delivery, but most thought the ’03 offered a better overall motor package.

|

| In 2003, WP (formerly White Power) had a well-earned reputation for subpar performance. The 48mm USD forks on the 250SX certainly lived up to this expectation. They were poorly set up, with overly soft springs and heavy damping. The resulting droopy front end hung down in the stroke and pounded rider’s hands over rough terrain. The highlight of the ’03 KTM’s front end was definitely the excellent Brembo front brake. Even in 2003, KTM was setting the standards for braking performance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

In 2003, it was the chassis that really let the 250SX down. At the time,.European machines were typically tuned more for the faster tracks found on the Grand Prix circuit. As a result, cornering usually took a back seat to high-speed stability. For ’03 KTM totally revamped the 250SX’s chassis in hopes of better appealing to the American consumers. They steepened the head angle a half-degree, lengthened the swingarm 10mm and changed the fork offset all in the pursuit of sharper turning. To say the result of all this tinkering was not a success would be quite an understatement.

|

| If the rest of the bike had been as good as the KTM’s motor in 2003 it would have been the bike to beat in the 250 class. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

When KTM tried to tighten up the 250SX’s handling, they ended up ruining the one thing it had previously done well. The ’02 chassis was no sharp turner, but at least it was stable and sure-footed at speed. When KTM redesigned the chassis for ’03, they ruined the bikes high-speed stability, while not improving the turning one iota. The new chassis was busy and prone to violent headshake at speed. Even worse, the front end provided absolutely no bite and pushed in the turns. The overall handling package was erratic and an absolute handful.

|

| The WP PDS shock on the 250SX was absurdly stiff and prone to kicking under braking. While the “no-link” rear could be made to work outdoors with proper set up, it was not up to the demands of professional supercross. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

Unfortunately, the suspension setup on the 250SX did the rest of the bike no favors. As it came from the factory, the KTM was unbalanced and offered an unbalanced stance (low in the front and high in the back). The WP shock was too stiff and prone to kicking sideways in braking bumps. It offered a “dead” feel that off-road riders liked, but terrified those looking attack a set of stadium whoops. With some tinkering, the no-link rear suspension could be made to work, but no amount of tuning was going to make it react like a link-equipped bike on a Supercross track. It was lighter, simpler, easier to maintain and probably played a role in the bikes prodigious horsepower figures (by allowing a straighter intake tract), but just not made for racing in the stadiums.

|

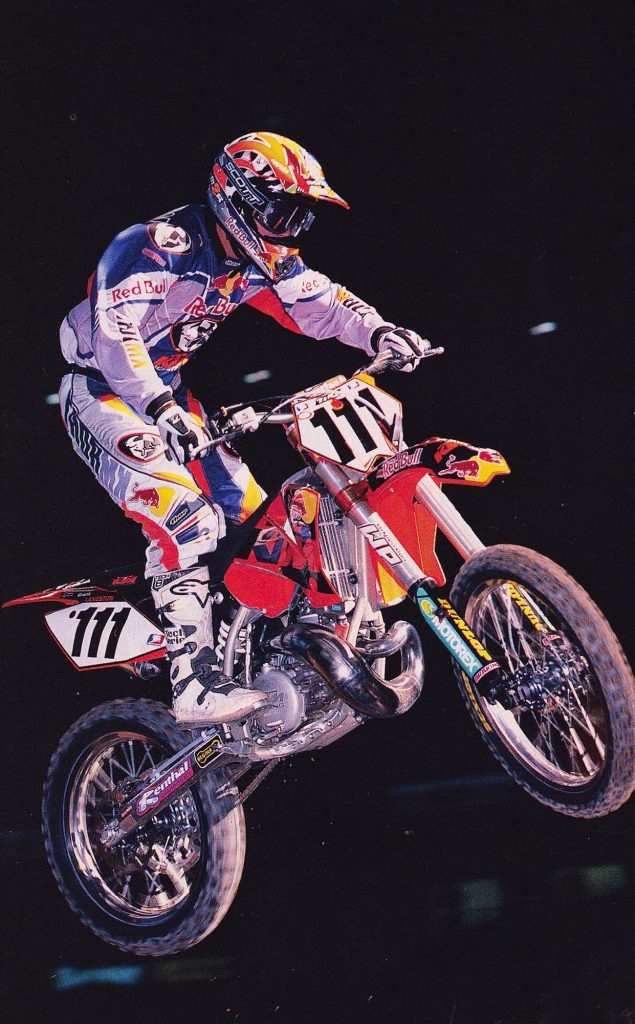

| Due to the nasty AMA Pro Racing-Jam Motorsports debacle, we ended up with the irrelevant “World Supercross Championship” in the early 2000s. Jeremy actually raced two of these rounds on the KTM before deciding the bike was too bad to continue. At the first round of the AMA series in Anaheim Jeremy would announce his retirement and put an end to his career as a full-time racer. Photo Credit: Transworld MX |

Up front, the 48mm WP forks were equally poor in performance. They were too soft initially and then harsh in the mid-stroke. To get decent performance out of them it was necessary to install stiffer springs and re-valve the damping. On top of the mediocre performance, they also liked to eat seals and bushings at an alarming rate. With all of that, it was safe to say that KTM was not going to win any suspension awards in 2003

|

| The silencer on the ’03 looked cool but liked to eject its retaining bolts on a regular basis. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

Detailing on the KTM was one bright spot on the Austrian rocket. The hydraulic clutch was flawless and offered superb performance. The Brembo brakes offered works-like performance and easily outclassed the Japanese competition A Renthal Fat Bar was standard equipment and worlds better than the pathetic steel bars on other bikes. Fit and finish were excellent, with quality parts throughout and careful construction. Even the tank decals were extremely durable and stayed on the bike well past the first pressure washing. On the not great side were the sprocket and silencer bolts, which were perpetually coming loose and the general usage of non-standard bolt types and sizes. If you bought a KTM, you better stock up on Torx heads, or you were going to be in for a world of aggravation.

|

| In 2003, KTM was still trying to come to grips with the American motocross market. Their bikes offered blazing fast motors but saddled them with medieval chassis. For the Austrian faithful, it would take a few more years and steady had of a Belgian five-time World champion to bring them into the motocross mainstream. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

In hindsight, it is really not hard to see why Jeremy McGrath bailed on his 2003 KTM contract. At the time, 250SX was still an unfinished product. It had the firepower to run at the front, but none of the finesse to make use of it. After a decade of riding great bikes from Japan, the deficiencies of the Austrian machines were glaring to the seven-time champ. In 2003, the turn-around of KTM from niche player to motocross power was still very much work in progress. They were certainly on the road to respectability, but not yet ready to handle one of the sport’s greatest riders, on the world’s biggest stage.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com