For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s 1992 CR500R.

By: Tony Blazier

In spite of its radically changed appearance, the 1992 Honda CR500R was not much different than the machine it replaced. Photo Credit: Honda

In spite of its radically changed appearance, the 1992 Honda CR500R was not much different than the machine it replaced. Photo Credit: Honda

The nineties were a unique time in the world of motocross. During the early part of the decade, the entire motorcycle industry seemed to lose its mind and throw styling restraint out the window. Starting with the ’91 model year, good taste went on hiatus and all bets were off. First, Yamaha changed from its tasteful white and red, to white and pink (or Magenta if you listened to the Yamaha’s PR folks). Then, Suzuki puked all over their beautiful 1990 RMs and turned them into some kind of rainbow-striped clown cars.

In 1992, Honda ditched their iconic wing graphic for the first time and went to this kindergarten-level “CR” graphic on the shrouds. At the time, I hated this move and twenty-five years have not done a lot to disabuse me of that opinion. Photo Credit: Honda

At Honda, this insanity manifested itself in the form of tiger stripes and giant cartoon “CR” graphics on the 1991 models. In ’92, they upped the ante with a color swap from understated orange to glow-in-the-dark neon red. This new color was dubbed Nuclear Red and it was by far the boldest look ever to grace a Honda motocross machine. Bright and almost translucent, the Nuclear Red was closer to a day-glow pink than any previous shade Honda had employed. With its white tank, bright colors and non-traditional graphics, the 1992 Honda CR500R looked like a whole new breed of CR.

The 491cc power plant on the 1992 Honda CR500R could trace its roots all the way back to Honda’s monster-motors of the mid-eighties. In spite of lacking the Kawasaki’s variable exhaust port, it provided a strong and competitive powerband. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The 491cc power plant on the 1992 Honda CR500R could trace its roots all the way back to Honda’s monster-motors of the mid-eighties. In spite of lacking the Kawasaki’s variable exhaust port, it provided a strong and competitive powerband. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Pinky Pie: The color on the 1992 CRs was a unique sort of pinkish-red Honda coined Nuclear Red. When new, it was only slightly pink, but once it spent 10 minutes in the sun, the whole bike turned to a shade of salmon. After riders complained about the new color’s lack of durability, Honda dialed back the pink for ’93 and adding back more red into the mix. Photo Credit: Stephane LeGrand

Pinky Pie: The color on the 1992 CRs was a unique sort of pinkish-red Honda coined Nuclear Red. When new, it was only slightly pink, but once it spent 10 minutes in the sun, the whole bike turned to a shade of salmon. After riders complained about the new color’s lack of durability, Honda dialed back the pink for ’93 and adding back more red into the mix. Photo Credit: Stephane LeGrand

By 1992, the writing was already on the wall for the 500 class. Both Yamaha and Suzuki had already pulled out of the division, and Honda and Kawasaki were no longer giving their big bores the latest in technology. With the ’92 models, the CR500R and KX500 were already two redesigns behind their 250cc stablemates. Each year, they would get a few suspension tweaks and some Bold New Graphics, but the basic designs remained stuck in the 1980s.

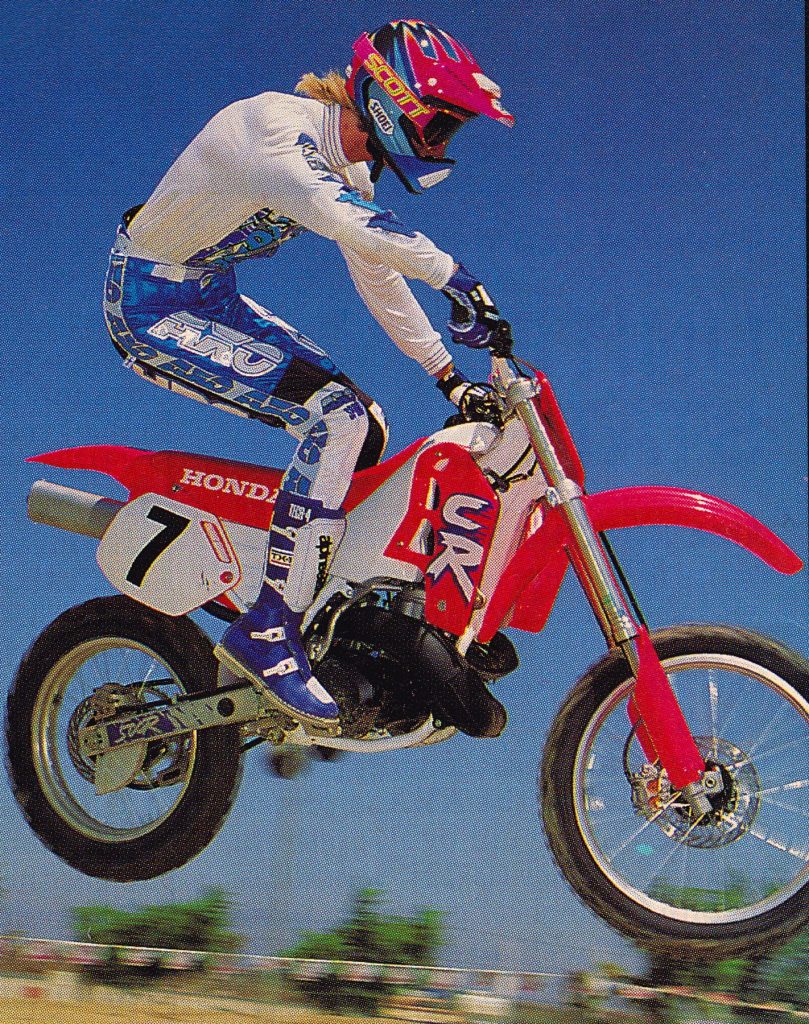

In spite of its size and power, the ’92 CR500R was a capable flier. “Too Tall” Tim Telford demonstrates. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

In the case of the 1992 CR500R, nothing illustrated that more than the design of its 491cc two-stroke motor. Simple, powerful and stone-reliable, the Honda’s motor dated all the way back to the mid-eighties and did without any sort of exhaust valve to broaden its performance. Other than liquid cooling, it was basically the same sort of motor that riders like Roger DeCoster and Brad Lackey would have used two decades before. In spite of this simplicity, however, the CR continued to provide a potent and competitve motor package.

Without the benefit of a variable exhaust port, the old-school CR power plant had a hard time matching the KIPS-equipped KX500 in terms of raw performance. In spite of this deficiency, however, many riders preferred it for its responsive delivery, lack of vibration (compared to other 500s, it still shook like a paint shaker compared to anything else) and stone-ax simplicity. Photo Credit: Honda

Without the benefit of a variable exhaust port, the old-school CR power plant had a hard time matching the KIPS-equipped KX500 in terms of raw performance. In spite of this deficiency, however, many riders preferred it for its responsive delivery, lack of vibration (compared to other 500s, it still shook like a paint shaker compared to anything else) and stone-ax simplicity. Photo Credit: Honda

When the CR500R’s liquid-cooled motor first made its debut in 1985, it was a virtually unrideable brute. The powerband was incredibly explosive and extremely difficult to control. Even pro riders found it unmanageable and Honda quickly realized they would need to tame things down to keep from losing even more buyers to the 250 class. What followed, was a systematic program to tone down the ferocious power of the monster-motored CR. After ’85, each successive iteration of the CR500R dialed back the brutality and upped the rideability in an effort to tame the savage beast.

The Showa inverted forks employed on the ’92 CR were grim at best. In stock condition, they hung down in the stroke and pounded the rider’s hands like a set of jackhammers. With a spring swap and re-valve, they could be made useable, but they were never going to be in the same league of the Kawasaki’s excellent Kayaba units.

In 1992, that finishing school program reached its conclusion with the easiest-to-ride open class Honda in a decade. Because the CR500 still lacked a power valve, Honda had gone to truly old-school methods to take the bite out of the five-oh-oh’s power delivery. The first of these changes was a simple alteration of the CR’s final drive ratio. By going from a 14/51 to a 14/49 final drive, the engineers were able to both mellow the throttle response and make the bike feel as if its power pulled farther and over a broader spread. This was an old trick that savvy tuners had used for decades to make torquey beasts like the CR more manageable.

At least that pink plastic did go nicely with the pink in all the gear in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The second trick Honda employed was to choke off the CR’s exhaust. Typically, motocross exhausts are tuned to be as free-flowing as possible, but for ’92. Honda went the opposite direction. Ever since 1989, the stock CR500R had used a unique muffler that was comprised of two separate chambers, with a dead space in between. This was designed to both smooth the power and lower the bike’s noise output. For 1992, this design was put of steroids and literally doubled in size. This made the bike both very quiet and very mellow. With the stock exhaust in place, the CR’s muffler extended nearly to the end of the rear fender

Jean-Michel Bayle made riding a 500 look like a walk in the park. His incredibly fluid riding style was perfect for taming the 60hp brutes. After waxing the field in ’91, Bayle was only mildly interested by the time the 500 Nationals rolled around in ‘92. He would just cruise around half the race, then kick in the afterburners, showing the field his taillights when the mood struck him. It seemed his main motivation was to mess with his Honda teammate Jeff Stanton.

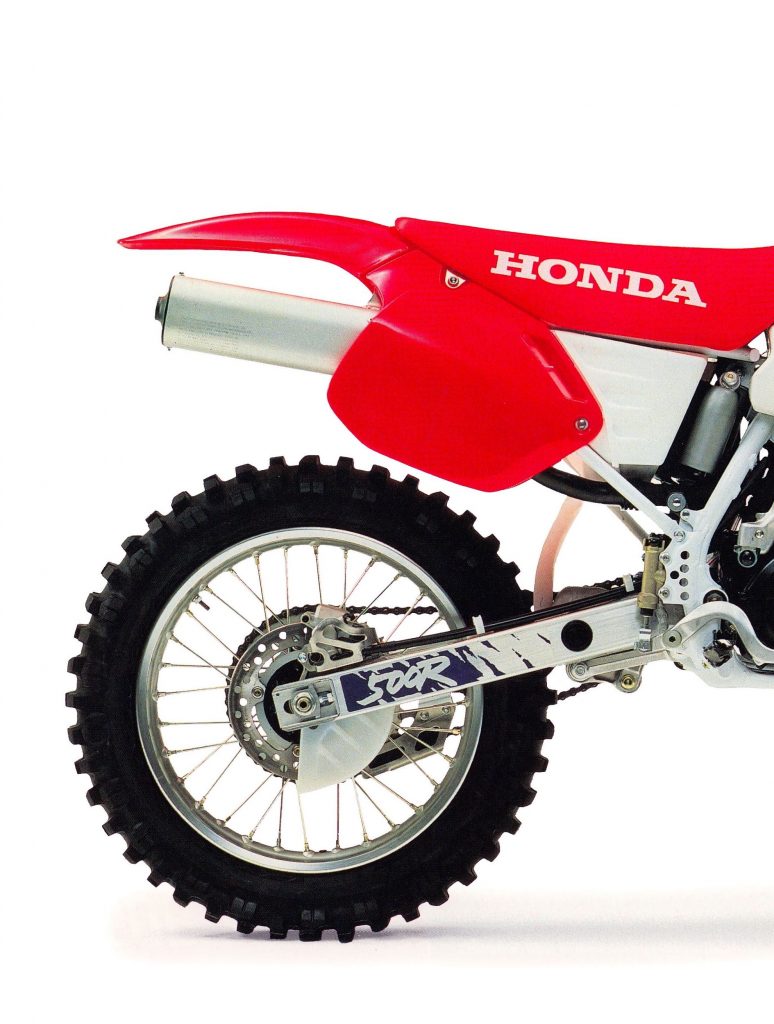

The stock Showa shock on the 1992 CR500R worked only marginally better than the sub-par front forks. In the rough, it kicked and skittered about, transmitting sharp hits directly to the rider’s backside. With a stiffer spring and some fine-tuning, the performance improved substantially, but it was never going to compete with the KX500’s excellent Uni-Trak rear suspension. Photo Credit: Honda

In stock condition, the ’92 CR500R put out a smooth, electric style of power. It carburated perfectly and pulled strongly off the bottom, before climbing into a meaty midrange surge. Top end power was not the bike’s forte, but most savvy 500 pilots knew better than to wring a 491cc motor out like it was a 125 (lest ye be swatted like a fly). Even with the taller gearing and restrictive exhaust, the CR’s throttle response was instant and very responsive. Any application of throttle sent the big 500 hurtling forward in a crescendo of torque and roost. In terms of maximum power, it was not quite as potent as Kawasaki’s KIPS-equipped KX500, but it was quicker to rev, better jetted, and smoother overall. It also vibrated less, shifted better, and was far easier to service. For certain applications, the KX might have been better, but for pure motocross, most people rated the CR’s new power package the best of ’92.

Braaappp: If you happened to have escaped from a loonie bin in ’92 and were looking for the old CR500R’s arm-stretching midrange thrust, it was only an exhaust system away. If you dropkicked the restrictive stock exhaust for a Pro Circuit system, both that lovely sound and that ridiculous hit were back in spades. Photo Credit: Stephane LeGrand

On the chassis front, the CR500R was the most motocross-focused of all the ’92 500s. Whereas the KTM, Yamaha (if you wanted to throw the WR500 into the mix), and Kawasaki open-classers were at home off-road and on the track, the narrowly-focused CR was a single-purpose machine. With its quick handling and a nasty headshake, it was not really the best bike for blasting across Baja. On a tight motocross track, however, it had few peers. Turning was razor-sharp and the red machine could cut under any other 500 with ease. While still a big bike, it felt far lighter and more nimble than its 235-pounds would indicate. Due to its snappy delivery, quick handling, and slim (for a 500) layout, it felt much more like an ultra-powerful 250 than a traditional 500.

While much beefier than its 250 Honda stablemate, the ’92 CR500R’s layout was by far the sleekest in the 500 class. Compared to the big and bulky KX500, the slim and trim CR500R felt like a 125. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1992, it was on the suspension end of things than the CR500R package started to fall apart. At the time, Honda was coming off three-years of truly terrible fork designs. Ever since converting to inverted forks in 1989, they had not been able to get a set of forks to do an even passable job of absorbing the track. Even though they seemed to work better on the 500 than they did on the smaller Honda machines, they were as far away from good as could possibly be.

With snappy power, excellent ergos and sharp geometry, the CR500R was the scalpel of the 1992 500 class. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

For 1992, Honda tried to turn things around by bolting on an all-new 43mm Showa fork to the CR500R. This new fork was 2mm smaller than 1991 in hopes of reducing the harsh feedback riders had complained about since the move to the inverted design in ’89. Internally, the new forks featured a redesigned cartridge system with tough alumite coatings to reduce stiction and oil contamination. To fine-tune performance, the new fork added a 17-position rebound damping adjuster to go with the 14-position adjustment for compression.

In 1992, Honda was the last manufacturer still using an 18″ rear wheel. Photo Credit: Stephane LeGrand

On the track, these new forks were improved over the grim 1991 offerings, but still not very good by any other measure. In stock condition, they were too soft initially and harsh in the midstroke. They hung down in the stroke and banged to the stops and big hits. With the stock 0.38 springs in place, the forks were too soft for anyone but an absolute novice. Thankfully, however, they were not as absolutely hopeless as the old 45mm versions had been. With stiffer springs installed and some oil level fiddling, they became at least useable.

This picture of the rear fender gives you a good look at the uniquely pink flavor of the Nuclear Red plastic on the 1992 CRs. Photo Credit: Stephane LeGrand

Out back, the picture was a little better than up front. Much like the forks, the stock Showa shock was undersprung for the bike’s power and weight. This made the bike harsh under power and prone to bottoming on big hits. With a heavier spring installed, however, things got much better. This allowed the bike to stay up in the travel on small chatter and prevented a metal-to-metal clank when trying to ride like Jean-Michel Bayle. With this simple mod, the bike was much more raceable, but still nowhere near as plush as the Kawasaki’s excellent KYB damper.

In ’92 these were the best brakes in motocross. Amazingly, compared to a modern bike they feel woefully underpowered. When you ride a bike like this now, it still feels plenty fast, but the brakes are where you really feel the march of time. Photo Credit: Stephane LeGrand

Detailing on the ’92 CR500R was excellent for the time. Overall reliability was phenomenal and it was not uncommon to race a CR500R for an entire season without having to rebuild the motor. Clutch life, parts availability, fit and finish, and overall build quality were the best in the business. A new master cylinder for ’92 added a shorty lever and a great deal more adjustment to the CR’s already excellent brakes. Power, feel and pad life were excellent and far better than anything else found in the class. When you have 60 horsepower, getting stopped is key, and nobody had better brakes than the CR in ’92.

When Jeff Stanton moved to team Honda, it was assumed he would eventually be a 500 National Motocross champion. Even on his outdated air-cooled Yamahas, he had always been at the front. Somehow, however, that expected outcome never materialized for the six-time champ. In 1992, Stanton was incredibly close to claiming that elusive 500 title, but in the end, he lost out by a mere three-points to Kawasaki’s Mike Kiedrowski. Photo Credit: John Valdez

On the meh side of the ledger were the CR’s punny footpegs (half the size of the floorboards found on the Kawasaki), old-school bodywork (slimmer than the KX, but still two generations behind the CR250), and fade-prone plastic (the Nuclear Red quickly faded to a light pink after a few hours of sun exposure). In the toss-up category, we had the CR’s 18″ rear wheel, which some riders praised and others found outdated. In ’92, Honda was the only manufacturer not ready to move to the larger hoop and that made the bike better for play racers (less susceptible to flats), but less attractive to pros (who preferred the more accurate feel of the 19″ wheel).

If you were looking for the longest lasting, most reliable motocross machine money could buy in 1992, you needed to look no farther than the Honda CR500R. Even though it lacked the high-tech credentials and suspension finesse of the KX500, it more than made up for it with its buckets of smooth power, nimble handling, and bulletproof reliability. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

If you were looking for the longest lasting, most reliable motocross machine money could buy in 1992, you needed to look no farther than the Honda CR500R. Even though it lacked the high-tech credentials and suspension finesse of the KX500, it more than made up for it with its buckets of smooth power, nimble handling, and bulletproof reliability. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1992, Honda offered a big bore beast with a heart of gold. Simple, reliable, and absurdly powerful, Honda’s take on the ultimate open class racer offered 250 handling, 500 torque, and grade-school graphics. With its poorly set up suspension, short-lived plastic, and vicious headshake it was far from perfect, but with a little fine-tuning, it was a lethally-effective motocross weapon.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com