For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at the last of the alloy tanked Yellow Zonkers, the 1978 Suzuki RM250C.

For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at the last of the alloy tanked Yellow Zonkers, the 1978 Suzuki RM250C.

By: Tony Blazier

|

|

When I think of a seventies RM this is the one I picture. Guys like DeCoster and DiStefano made these bikes famous. While they may not have looked quite as trick as the monoshock YZ’s, for many people they were actually better bikes. |

Throughout the first half of the seventies, Suzuki lacked a credible production motocross racer. Their TM line was a pale imitation of their awesome works bikes, panned by critics and riders alike. All that changed in 1975, when Suzuki debuted the first of their incredible RM race bikes. The new RM’s were light years better than the TM’s had been, and competitive race bikes right out of the crate. The RM250-A and its successor, the RM250-B were some of the best and most popular bikes available in the 250 class at the time. Their success was not limited to the showroom either. With Tony DiStefano at the controls, RM250’s would capture the 250cc National Motocross title three straight times from 1975-1977. The late seventies and early eighties were a great time to be on a Suzuki.

|

|

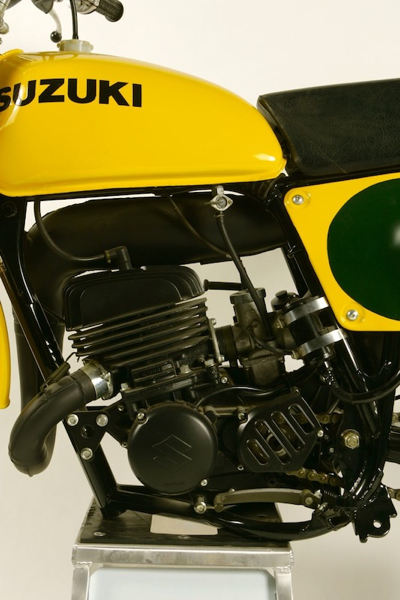

The RM-C’s 246cc two-stroke mill was real torquer. Power was all low-to-mid, with a healthy hit and little top-end pull. It was fast and effective, but requited a fast left foot and a quick right wrist to get the most out of its short power spread. |

The 1978 RM250-C is an interesting machine. In 1978 there were actually two RM250’s offered for sale. Halfway through the year, Suzuki came out with what it dubbed the 78 ½ RM250C-2. The 78 ½ C-2 would see upgrades to the RM’s motor and suspension to try and keep pace with Suzuki’s fast moving competitors. The 78-250-C model would be the last of the 1st generation RM’s, which began with the RM250-A. It would be the last to use Suzuki’s iconic alloy tank design (to be replaced with a far less attractive plastic one on the RM250C-2), and make due with a steel swingarm. The race for long travel had begun in earnest, and the switch to the C-2 mid year signaled Suzuki’s desire not to be left behind.

|

|

The RM motor was a pretty standard mid-seventies Japanese 250. It used a two-pedal steel reed-valve induction and 36mm round slide Mikuni for carburation. The ignition was a maintenance free electronic set up, far superior to the less reliable points employed on most bike a few years earlier. Advances in metallurgy and electronics contributed greatly to the increased reliability bikes like the RM began to enjoy in the late seventies. |

The 78 RM250-C featured a pretty conventional-for-the-time motor. The 246cc air-cooled, two-stroke single used a 67mm x 70mm configuration and reed-valve induction. This was combined with a 36mm Mikuni round slide carburetor and a slightly longer stroke to provide a very torquey power delivery. The ignition did away with the points used on earlier machines, replacing them with a much more reliable, maintenance free, electronic ignition. Putting power to the ground was a smooth shifting five-speed transmission.

|

|

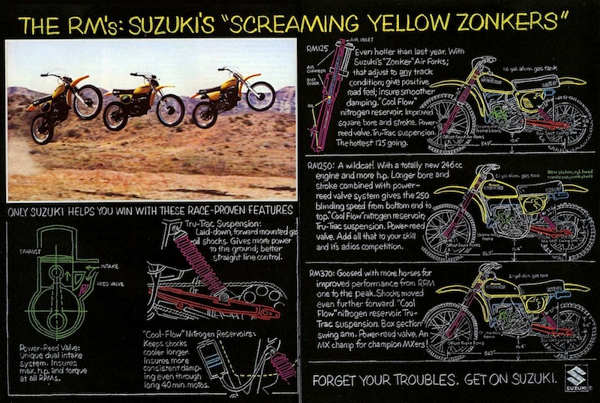

You just don’t see cool ads like this these days. How can you not love a bike called a “Screaming Yellow Zonker”? Hell, I don’t even know what a Zonker is, but I want one. |

For ’78 Suzuki focused on making the fast, but hard-to-ride RM250-B motor easier to manage. They increased the volume of the transfer ports, revised the ignition and reshaped the expansion chamber all in the hopes of giving the bike more low-end torque. The result of all this massaging was a powerband that focused its power much lower in the power curve than previous RM 250’s.

|

|

In the mid-seventies, The Man made these RM’s look unbeatable. Even though his bikes shared little with the stock machine, his aura added to the overall mystique of the brand from Hamamatsu. |

|

|

One of the big reasons for the ’78 RM’s more torque delivery was this new pipe. The RM-C’s new expansion chamber was shorter and fatter than the B models had been, in order to beef up the power curve. That combined with some porting changes and a remapped ignition, shifted the previously high-strung RM’s powerband much lower into the curve. |

The RM-C came out of the hole with a strong blast of torque right off idle. From there, the power would pull strongly into a solid mid-range hit, before tapering off as rpm’s rose. Unlike the RM-B, there was no top-end past the healthy mid-range hit. The C model was best ridden by shifting right in the meat of the torque curve. It was a classic “short-shift” motor. This did not make it necessarily faster than previous RM’s, but it was quicker from turn to turn and easier to keep on the pipe.

|

|

By 1978, the RM’s paltry 9.8” of travel were starting to look very last year. With bikes like the radical new ’78 CR250R Elsinore pushing the suspension envelope up to a full 12 inches, the RM was falling behind in the suspension PR wars. Thankfully, size is not everything, and the RM’s slightly shorter forks actually worked better than some of the longer travel designs of the competition. In ’78 these were darn good forks. |

On the suspension front, the RM-C was a mix of old and new. The front forks were all new for ’78, featuring the addition of air adjustability. Unlike today, there was no damping adjustability built into forks of this era. If you wanted to adjust the performance, you had to change oil viscosity or volume internally. In the mid seventies, manufacturers began adding schrader valves to the fork caps so riders could add or remove pressure to tune performance. It was by no means a perfect way of adjusting performance, but it could be used to fine tune ride height and compensate for too soft of a spring in a pinch. Believe it or not, this addition was big news in ’78.

|

|

The ’78 RM-C models saw the last of the alloy tanks (at least for 30 years, until the current RMZ brought them back). The ’78 ½ RM-C2 would usher in the era of the plastic tank. Although less prone to dents, the plastic tanks guaranteed your decals to peel off after the first ride. That combined with their generally ugly shape makes them far less appealing to me than these cool mid-seventies designs. |

The new fork featured 9.8” of travel to go with its enhanced adjustability. This was a full two inches less than the all-new ’78 Honda CR250R Elsinore offered, and quickly looking very outdated. Performance wise, the new fork was regarded as excellent for the time. It provided a smooth, controlled ride and gobbled up most track obstacles with aplomb. It was, however, very sensitive to the air pressure adjustments. With the recommended 20 pounds of pressure in the fork, the ride could be slightly harsh and give the bike a bad case of understeer. If however, you lowered that pressure to 18 pounds, the ride smoothed out and the front-end push went away. It was a good fork, but it needed to be properly set up to get the most out of its performance.

|

|

While the RM’s forks were pretty good, the same could not be said for its abysmal stock shocks. These babies were overly stiff and prone to packing down in successive bumps. They were universally disliked and most serious racers tossed them for a set of aftermarket units. Brakes,on the other hand, were considered excellent both front and rear. |

In the rear the picture was not quite as rosy. The laid down “Tru-Trac” shocks provided a decent, if not overwhelming, 8.6” of travel. Again this was far less than the Honda and Yamaha had in ’78. They were simple, non-adjustable gas/oil units, featuring small remote reservoirs on each shock. As delivered, they were set up with too stiff of a rear spring and too much rebound damping. They worked well on big jumps and hard hits, but deflected off smaller obstacles. If faced with successive bumps, they would tend to pack down and after about the forth hit start swapping side to side. They were considered pretty bad even in 1978, and since there was no real way to alter their performance, most serious riders just replaced them with aftermarket units. This was one of the issues addressed by the 78 ½ RM-C2 with its much improved shocks and increased suspension travel.

|

|

This silencer probably weighs double what a current four-stroke pipe weighs. This cast iron looking boat anchor was actually state of the art in ’78. MXA praised it for its exhaust note and performance. My how times have changed. |

These early RM’s were not particularly light machines, clocking in a over 230 lbs. That actually seems like a lot if you look at how little motorcycle is there. Even though there are no radiators, power valves, or big beefy frames, the use of low grade steel and heavy components made these bike actually heavier than their modern equivalents. On the bright side, even though the RM was slightly overweight, with proper set up they were good handlers. Turning was not quite up there with the best bikes of the day (it would take a few more years for Suzuki to earn its reputation for unrivaled turning), but it would hold an inside line if the rider kept his weight forward. Stability, however, was very good with an inch longer wheelbase (57.1 inches) than the ’77 model and very little headshake. The only real chinks in the RM’s handling repertoire were its recalcitrant shocks, which could kick the rear sideways at unexpected moments.

|

|

The RM250-C was a darn good bike, quickly overshadowed by the relentless march of technology that typified mid-seventies motocross design. These 1st Gen RM’s were game changers in their day, blending performance, reliability and affordability into a sweet package that was hard to beat. |

The 1978 RM250-C is a bit of an oddball. It was a bike that was rendered obsolete only a few months after its introduction. The ‘78 ½ RM250-C2 featured a better motor, better suspension and better handling. The RM-C on the other hand, was little more than a souped-up ’76. In spite of its shortcomings, the RM250-C was an excellent motorcycle. It may not have had the most suspension travel, but it was a very good race bike. It handled well, was fast and was easy to ride, plus it had good forks and was reliable. That was a combination that won Suzuki a lot of races in the late seventies.