For this edition of Classic Steel we were going to take a look back at one of Kawasaki’s best early machines, the 1979 KX125A-5.

By: Tony Blazier

Prior to 1979, Kawasaki was just not on most motocross racer’s radar. KXs were not being produced in significant numbers and most Kawasaki dealers were more interested in selling saddlebags than knobbies. While that situation was not about to turn around overnight, bikes like the A-5 went a long way toward getting riders to take another look at the green machines. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The seventies were an interesting time for Kawasaki. In the early part of the decade, they had produced some mildly successful off-road machines with their 100cc Centurion and 238cc Green Streak. Fast, but ill-handling, these early endeavors were not taken seriously as “real” motocross racers. Then in ’74, Kawasaki decided to jump into the deep end with a serious line of motocross racers of their own. The new KXs were Kawasaki’s attempt to carve out a slice of the burgeoning motocross market (and steal sales away from Honda’s runaway hit, the Elsinore). The new KX125 and KX250 turned out to be sub-par Elsinore clones in most respects and failed to make much of a dent in the off-road market. While Honda, Yamaha, and Suzuki plowed full-steam-ahead toward market domination, Kawasaki seemed content to focus mostly on street machines throughout the majority of the decade.

The A-5’s air-cooled reed-valve single was a real torquer for a 125. The 124cc mill pulled strongly from very early in the powerband, before climbing into a healthy midrange blast. Top-end was notably lacking, but the KX mill was fast, easy-to-ride and effective. If not for its clunky transmission, the KX would have taken home the honor for the best motor of ’79. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

It was not until 1978 that Team Green started to take motocross seriously. In ’78, Kawasaki scrapped the original (and by now very outdated) ‘74-’76 KX125 design and introduced an all-new motocross machine. The ’78 KX125A-4 was a much more competitive machine than its predecessors had been. It featured a fast, but pipey, pro-oriented motor, and lightweight chassis. In truth, the A-4 proved little more than a marketing exercise for Kawasaki. The manufacturer only produced 1600 of the A-4’s in total, meaning that if you were Joe Average you had very little chance of obtaining an A-4. Still, with riders like “Gassin” Gaylon Mosier and Jimmy Weinert at the controls, the new KXs did receive a good deal of publicity in 1978. It would not be until a year later, in 1979, that Kawasaki would finally signal that they were indeed serious about the motocross market with a competitive machine for the masses.

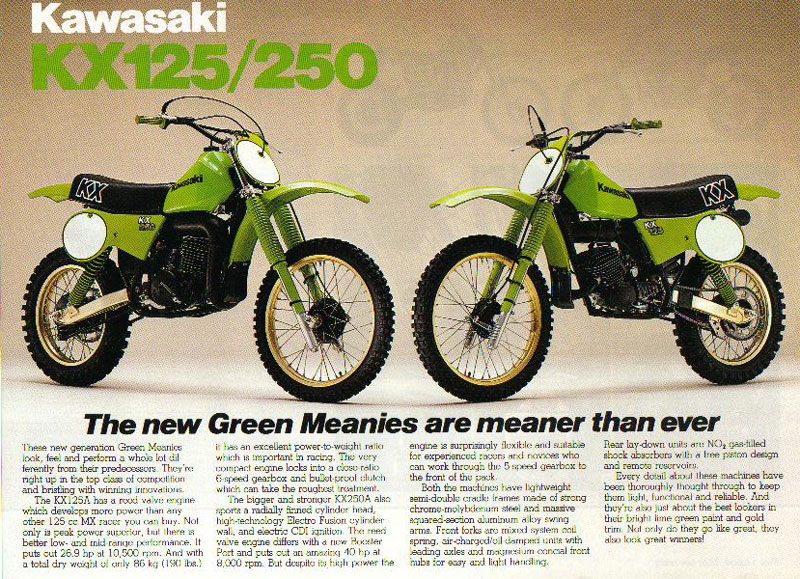

All-new for 1979, both the KX125 and KX250 were by far the most competitive green machines ever produced up to that point. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

All-new for 1979, both the KX125 and KX250 were by far the most competitive green machines ever produced up to that point. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The all-new ’79 KX125A-5 was finally a Kawasaki 125 that could really stand up head-to-head with the best from Japan. It featured a high-tech motor (for its time), a lightweight chassis and slick GP-inspired bodywork to go with its new long-travel suspension. The ’79 KX was truly ready to race right out of the box, and best of all, it did not require you have connections at Kawasaki in Japan to have a shot at buying one.

Kermit Krosser: The KX125A-5 was certainly a bold statement in 1979 with its head-to-toe coat of green paint and gold accents. Photo Credit: Cycle World

Kermit Krosser: The KX125A-5 was certainly a bold statement in 1979 with its head-to-toe coat of green paint and gold accents. Photo Credit: Cycle World

The A-5’s motor was considered remarkable for a 125 because of its broad, usable power curve. In the days before power-valves, very few 125s could actually be said to provide wide, easy-to-ride powerbands. Most were high-strung buzz bombs, which made all of their power over a very narrow range. In contrast, the A-5 produced a broad and torquey spread of power. Throttle response was particularly good, with a snappy delivery and none of the bog common to small bores at the time. Some of the credit for the KX125’s remarkable powerband probably went to its use of Boyesen’s excellent, dual stage reeds. At a time when most bikes were still using solid metal reeds, the new lightweight, dual-pedal Boyesen fiber reeds were a breakthrough in two-stroke performance. In ’79, Kawasaki licensed the use of Boyesen’s patented technology, and they were the only manufacturer to enjoy its benefits in power and response.

The A-5’s motor was quite advanced for its time. The six-speed mill featured an electrofusion cylinder liner instead of a heavy iron bore. This meant better heat dispensation and lighter weight, but no over-boring if you damaged the liner. The KX was also the only 125 in ’79 to use Boyesen’s new lightweight six pedal dual-stage reeds. Kawasaki licensed the technology directly from Boyesen and they helped to give the green machine the snappiest delivery of any tiddler that year. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The A-5’s motor was quite advanced for its time. The six-speed mill featured an electrofusion cylinder liner instead of a heavy iron bore. This meant better heat dispensation and lighter weight, but no over-boring if you damaged the liner. The KX was also the only 125 in ’79 to use Boyesen’s new lightweight six pedal dual-stage reeds. Kawasaki licensed the technology directly from Boyesen and they helped to give the green machine the snappiest delivery of any tiddler that year. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While the A-5’s motor was by far the easiest to use 125 in ’79, it was not completely without faults. The 124cc mill snapped to attention very low in the curve for a 125 and continued to pull into an excellent mid-range hit, but past that point, the little Green Meany petered out. Rather unlike most 125s, screaming the KX only resulted in more noise and less power. It was best to treat the A-5 like a big-bore, short shifting and using its excellent torque to blast you from turn to turn. Short shifting the transmission also aided in dealing with the KX’s true Achilles’ heel, its awful transmission.

At a 190 pounds ready-to-race, the ’79 KX was a real feather on the track. It was the lightest 125 made and a full 13 pounds lighter than a Honda CR125R. The light weight aided every facet of the bike’s performance and was a big reason the KX was one of the best handling packages on the track in 1979. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

At a 190 pounds ready-to-race, the ’79 KX was a real feather on the track. It was the lightest 125 made and a full 13 pounds lighter than a Honda CR125R. The light weight aided every facet of the bike’s performance and was a big reason the KX was one of the best handling packages on the track in 1979. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The six-speed cog box in the A-5 was notchy under the best of conditions and useless under duress. It was completely impossible to powershift the KX under a load (never a good trait in a 125). The only way to execute a positive shift was to back off the gas completely and use the clutch. This was a massive handicap on starts and tricky upshifts, where backing out of the gas cost precious seconds on the track. In addition to being virtually worthless, the KX’s tranny was also fragile and many riders reported failures throughout the year. In the final motor standings of ’79, the KX125 lost out to the excellent RM, but it bested the lackluster YZ and lethargic CR handily.

The stock Kayaba forks on the KX125A-5 punched out 9.8 inches of firm travel. Set up on the stiff side, they were excellent for fast guys but less forgiving to novices. The “cooling fins” at the bottom of the fork were purely cosmetic and offered no real advantage in performance

The stock Kayaba forks on the KX125A-5 punched out 9.8 inches of firm travel. Set up on the stiff side, they were excellent for fast guys but less forgiving to novices. The “cooling fins” at the bottom of the fork were purely cosmetic and offered no real advantage in performance

In 1979 the motocross world was knee deep in the middle of a suspension arms race. The quest for suspension supremacy was driving the manufacturers to extend the travel of their machines nearly every year. Up until ’79, Kawasaki had been behind in this battle, but the A-5 would herald the arrival of true long-travel suspension to the green machine. The new forks and shocks on the KX delivered nearly 10 inches of travel front and rear. That was short of the 11 inches offered by the Honda and Suzuki, but in line with the mono shock YZ in ’79. The KX’s Kayaba forks offered no external adjustments for damping, but the ride could be fine-tuned through the use of air pressure, oil viscosity and oil level.

Like the forks, the KX’s shocks were well suited to aggressive riding. Trail riders and novices were likely to find its settings too stiff, but experts appreciated their firm action and solid bottoming control. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In terms of actual performance, the KX’s forks were considered very good for their time. They were set up for faster riders, with heavy rate springs and aggressive damping. Slower or lighter riders found the ride too stiff, but with fine-tuning, they were acceptable for a wide range of pilots. In the ’79 suspension rankings, the Suzuki’s plush forks swept the field, with the Kawasaki coming in second. A close third was the Yamaha, with the positively terrible Honda bringing up the rear.

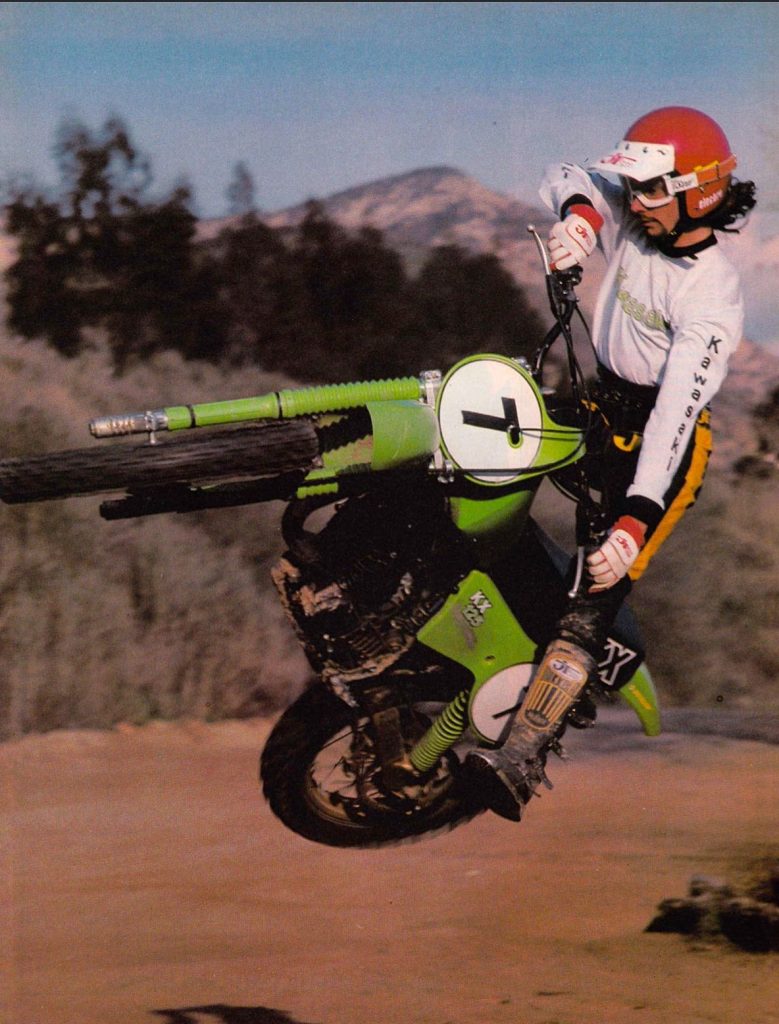

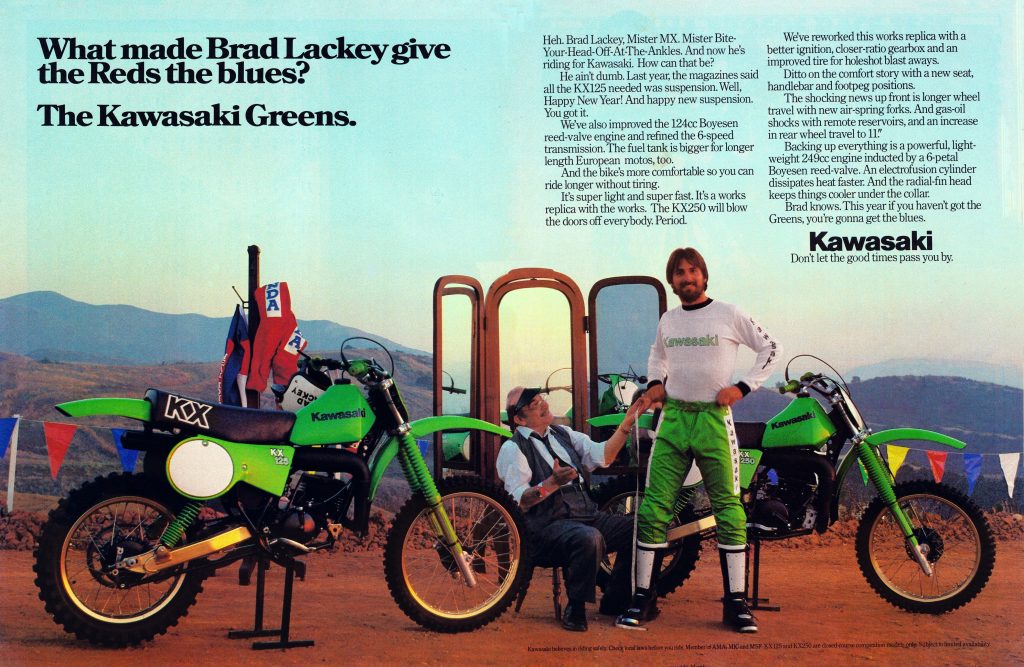

Kawasaki’s big push in 1979 started with the signing of long-time GP contender “Bad” Brad Lackey away from Team Honda. Brad’s stay with Team Green would be a tumultuous one, as mechanical DNF’s would haunt him throughout his tenure at Kawasaki. In ’81, Brad would make the switch to Suzuki and finally capture his long-sought 500 World Title the following year.

Kawasaki’s big push in 1979 started with the signing of long-time GP contender “Bad” Brad Lackey away from Team Honda. Brad’s stay with Team Green would be a tumultuous one, as mechanical DNF’s would haunt him throughout his tenure at Kawasaki. In ’81, Brad would make the switch to Suzuki and finally capture his long-sought 500 World Title the following year.

In the rear, the A-5 used twin Kayaba remote reservoir shocks punching out a total of 9.8 inches of travel. Like the forks, they featured no external adjustability save spring preload. The performance of the shocks was skewed toward faster riders as well, with stiff springs and damping. They were by no means plush, but they absorbed big hits well. In an era dominated by aftermarket shocks, the stock Kayaba’s were usable for the majority of riders. Only really fast riders, or those seeking more travel needed to go to aftermarket units on the KX. In terms of ranking, the KX once again finished behind the awesome Suzuki RM125, but well ahead of the too soft YZ and grim Honda.

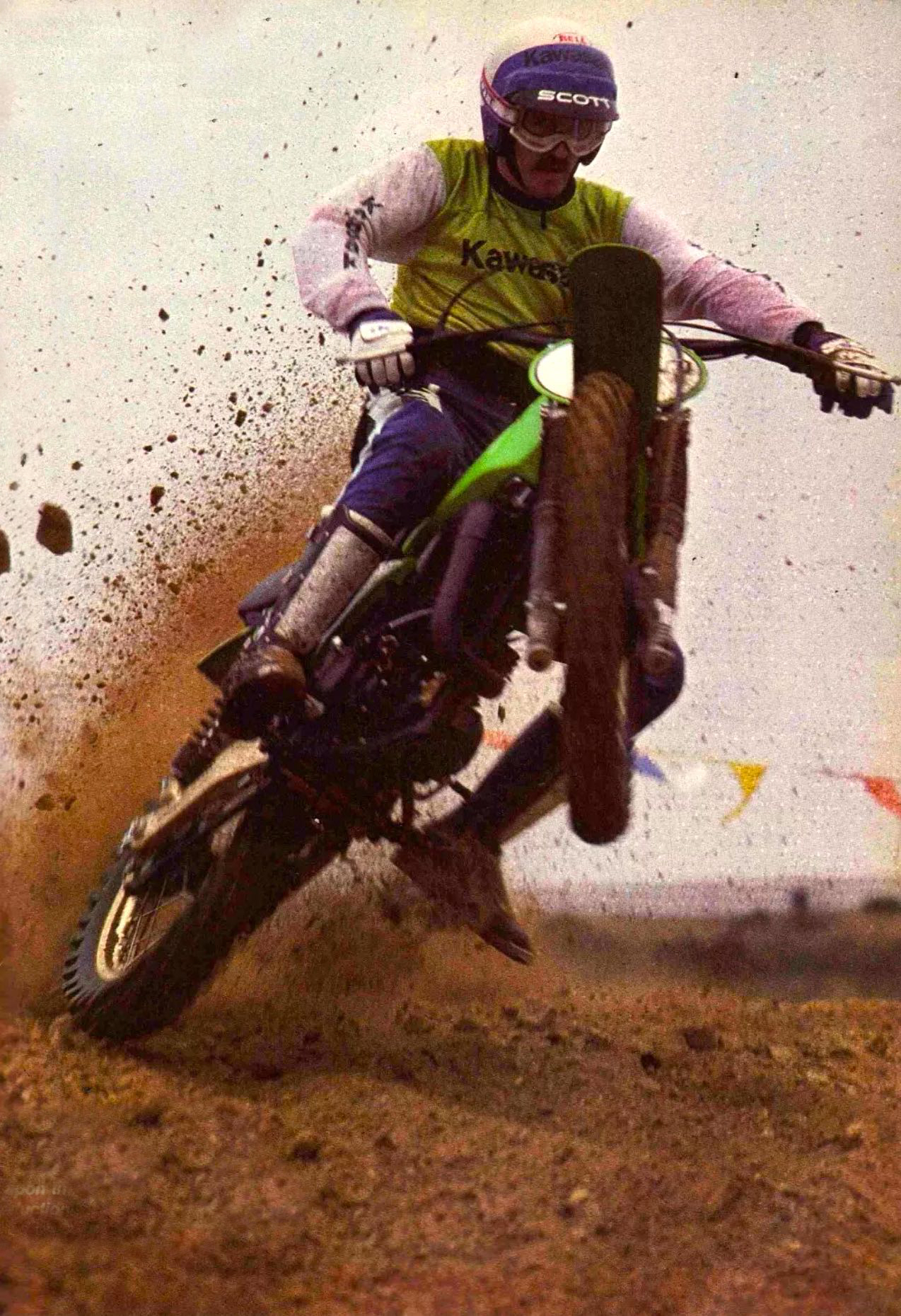

The KX was considered a real shredder in 1979. With its feather-light 190-pound weight, excellent chassis, and solid suspension, the KX offered one of the best all-around handling packages in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Cycle World

The KX was considered a real shredder in 1979. With its feather-light 190-pound weight, excellent chassis, and solid suspension, the KX offered one of the best all-around handling packages in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Cycle World

In the detailing department, the little KX was one pretty cool machine (as long as you liked green that is). Lime green was everywhere on the bike, right down to its shock springs and stock grips. The grips in particular (while pretty trick) were not well liked by riders. They were large, and made of a very hard compound that shredded tender hands in short order. The A-5’s plastic tank and side panels were new for ’79 and closely resembled the ones on Kawasaki’s GP racers. While the brakes on the KX were by no means fantastic, they did an adequate job of slowing down the lightweight machine and were considered on par with other tiddler offerings in ’79. One nice feature on the KX was its big and sturdy gold anodized aluminum swingarm. It was flex free, and a big improvement over the flimsy steel units found on bikes like the Honda Elsinore.

Braappp: With its snappy delivery and solid midrange burst, the KX125A-5 was one of the quickest machines from corner-to-corner in 1979. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Another feature working in the A-5’s favor was its super light weight. The new KX tipped the scales at a featherweight 190 pounds. This, combined with its well-sorted suspension gave the bike a light and airy feel. The A-5 also sat a little over an inch lower than most of the other 125s in ’79 and was one of the few bikes that could be sat on flatfooted by riders under 5’9″. In the turns the KX had no equal, it could snag the inside or bounce off a berm with equal skill. The only real quibble with the KX’s chassis was its somewhat odd ergonomics. The foot pegs were placed high and several inches farther forward than on most other bikes. This was combined with low, rearward mounted bars to give the KX a very cramped riding compartment. The transition from sitting to standing was particularly difficult for riders with long legs. Since most 125 pilots tended to be smaller by nature, this was less of an issue than on bigger machines. Even so, the KX was definitely better suited to Jeff Ward than Mike Bell.

In 1979, Kawasaki came roaring back into the motocross mainstream with a much-improved KX125. The new machine was light, well-suspended, fast, and damn fine-looking. If only its transmission had been up to the standards of the rest of the machine it might have unseated Suzuki’s RM125 as the best tiddler in the land. Photo Credit Stephan LeGrand

In 1979, Kawasaki came roaring back into the motocross mainstream with a much-improved KX125. The new machine was light, well-suspended, fast, and damn fine-looking. If only its transmission had been up to the standards of the rest of the machine it might have unseated Suzuki’s RM125 as the best tiddler in the land. Photo Credit Stephan LeGrand

The ’79 KX125A-5 was the start of something big for Kawasaki. After years of lackluster off-road offerings, Team Green pulled out all the stops and produced a real 125 contender. The KX was a few details away from greatness in ’79, with its cranky gearbox and odd ergonomics. Still, it did get a lot right; the motor’s power was a match for anything in the class and the suspension was ready for the track right out of the box. The A-5 was a sign that Kawasaki was getting serious about the motocross market and within a very few years, they would be a legitimate contender in every class. Big things have little beginnings, and for Kawasaki, their great small bike legacy starts right here.