A look back at a classic machine that started a new era.

A look back at a classic machine that started a new era.

By Tony Blazier

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at the machine that started the aluminum revolution, the 1997 Honda CR250R.

|

|

The 1997 Honda CR250R is certainly one of the most influential motocrossdesigns of the last 20 years. Its revolutionary twin spar aluminum frame has become the inspiration for motocross chassis over the last decade. When you compare it to a 2013 Honda, the 1997 frame may look absolutely massive and crude by comparison, but it is impossible not to see that they share a lot of the same DNA. |

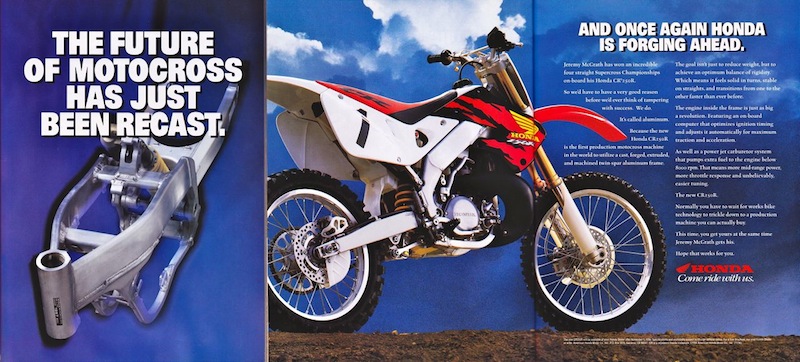

In 1996, Honda once again shocked the motocross world with the announcement of their revolutionary new CR250R motocrosser. The hype machine was kicked into full gear, as it was confirmed that new bike would indeed feature a full aluminum chassis. A staple for more than a decade on road racing machines, an aluminum chassis had never been tried on a production motocross machine up to that point. Honda’s new 1997 CR250R would be boldly going where no other production machine had gone before.

|

|

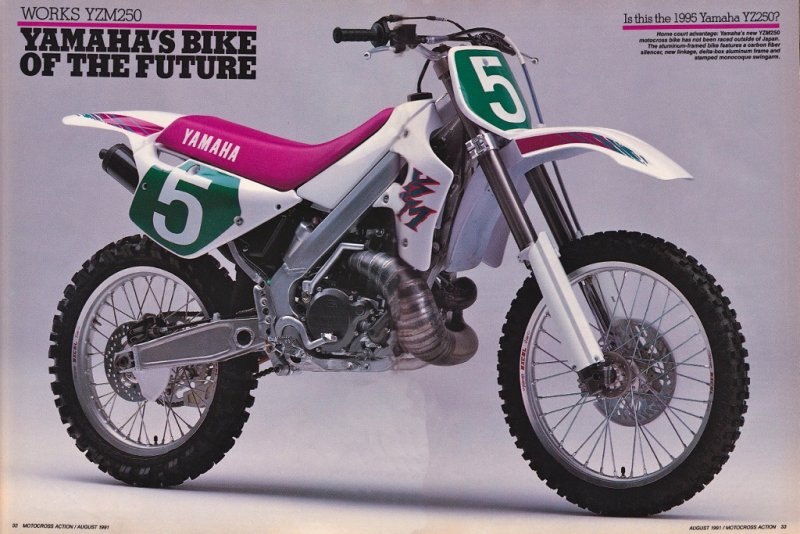

While Husky and others had flirted with lightweight alloy chassis on their works machines over the years, the first one to really make a splash was Yamaha’s 1987 YZM500. The YZM was a rolling experiment in motorcycle design, featuring a nearly all alloy construction and a one-off liquid-cooled motor. While the bike’s performance on the track left something to be desired, it scored a huge amount of positive PR for Yamaha at a time when they looked to be lagging far behind their Japanese rivals. |

While exotic alloys had never made their way onto production motocross frames, the Japanese and others had been experimenting with them for decades. As far back as the sixties, brands like Husqvarna had utilized super lightweight titanium frames on their works machines. While they proved too brittle and expensive for production, they pointed to a future where exotic lightweight materials could be used on off-road machines. In the eighties, Yamaha took up the torch of alloy experimentation with their incredibly trick YZM500. The YZM was a rolling work of art with its all aluminum chassis and monocoque rear subframe. Like the Husky, the YZM never lead to a production equivalent, but undeterred, the Big Four continued to flirt with aluminum framed works bikes throughout the early nineties.

|

|

While Yamaha never went to production with their revolutionary YZM500, they did continue experimentation with alloy chassis designs. This 1992 works YZM250 raced in Japan, shows an early version of an aluminum twin spar frame quite similar in design to the eventual one used on the ’97 CR250R. |

|

|

Like all the manufacturers, Honda experimented with many different designs before settling on the road race inspired twin spar common today. This 1994 RC250R is employing a more “conventional” design similar to the frame on a ’05-’13 YZ 2-stroke. In 1995 Honda also experimented with a perimeter design similar to an early 90’s Kawasaki KX. |

While never raced here in America do to our production rule, every year in Japan, a parade of ultra-exotic alloy chassis works machines would be on display in the Japanese MX Nationals. The designs varied greatly, from traditional single backboned cradles, to odd perimeter variations and road race inspired twin spars. Nearly every possible combination was experimented with in the search for the proper mix of flexibility and durability. Then in 1995, word began to leak out from Japan that Honda was indeed moving toward the production of an aluminum-framed motocrosser. Early spy shots reveled a huge road race style frame and super sleek bodywork. The bike looked like something from ten years into the future, with its massive frame spars and super long side plates. If the production machine turned out to look anything like the works version, it would just have to be the baddest machine ever to set wheels to dirt.

|

|

Believe the hype? When I first saw the new ’97 CR250R I was completely blow away. Overnight, my ’96 Honda CR250R looked completely outdated and I thought I had to have one. That is until one of my friends bought one and I had a chance to ride it. After two laps my hands were killing me and the bike was beating me to death. The new bike may have looked incredible, but in nearly every measurable way it was a step back from the year before. |

Based on looks alone, the new Honda had the entire industry worked into a froth in the summer of 1996. Early reports from magazines sang the bike’s praises as an all-new breed of CR. Deposits poured into dealerships, as riders hotly anticipated the arrival of the most radical new CR250R since the 1981 Elsinore introduced a monoshock and liquid cooling to the Honda lineup. Well, a funny thing happened on the way to the Motorcycle Hall of Fame- the can’t miss new CR turned out to be a greatly flawed machine.

|

|

This was the Atlas Missile of 90’s motocross motors. At the time, nothing pulled as hard or as fast as a CR250R. For ’97 Honda made a lot of minor changes to their tried and true deuce-and-a-half, including an industry first “power jet” carburetor. The result was a slight loss in bottom-end torque, but an increase in top-end rev. From the mid-range on up, the CR’s 249cc mill left the competition sucking its vapor trail. |

Early on in prototype testing the new chassis had shown a great deal of promise. Reportedly, the new bike was faster and better handling than the steel framed bikes Honda was using for comparison. Then testers started suffering failures. Aluminum can be tricky to work with under the best of conditions, and this was largely uncharted territory for Honda’s engineers. When you add in the unique stresses put on a motocross bike’s frame, you can see the opportunity for problems.

|

|

One of the interesting features that made their debut on the ’97 Honda CR250R was traction control (and you thought JGR was the first team to try and use traction control). The ignition was designed to monitor engine rpm every 35 milliseconds and if it detected a sudden spike, flatten out the ignition curve to compensate. While this system works great on cars with nearly 100% traction, it proved more problematic on the varied surfaces of a motocross course. In practice, the system was incapable of keeping up with the free revving motor and unpredictable surfaces. By the time it reacted, the hard-hitting CR was already laying down strips of rubber to the track. It was an excellent idea (much like the aluminum frame), in need of a little more refinement. |

A motocross bike’s frame is an incredibly complex piece of engineering. A frame needs to be stiff enough to absorb the major shocks of massive jump landings and high-speed impacts, while also having enough flex to provide good feedback and feel to the rider. Steel frames are excellent at the feel end of the equation, while alloys are excellent at fighting flex. The trick is to fine-tune the shape and thickness of the tubes to allow the best combination of both. By all accounts Honda was on the right track early on with the ’97 CR’s chassis, but once they started breaking, Honda started pilling on the metal. By the time the CR made production, that sweet handling chassis was a distant memory.

|

|

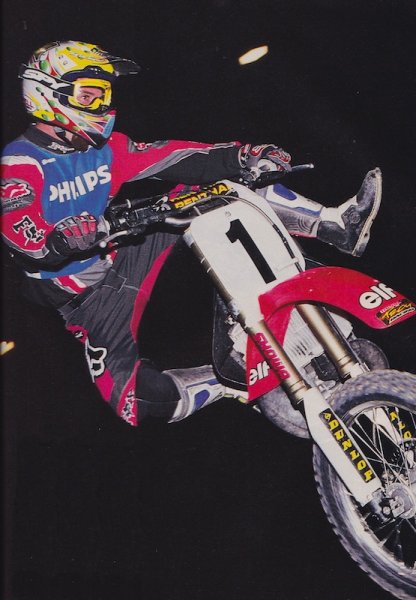

There are not many pictures of Jeremy on the ’97 CR250R and for good reason. He only rode them a few times in Bercy and Japan before bailing on his Honda contract and trying his chances on a Suzuki. In Bercy, on the new CR, Jeremy fought arm pump and looked absolutely mortal, getting beat easily by riders like Greg Albertyn (if that was not an indication something was wrong I don’t know what was). It was no secret Jeremy was unhappy with the new bike, and when Honda harassed him about riding on a Yamaha Wave Runner, he decided it was time to leave. Honda would not win another SX/MX title until 2002, when they would lure Ricky Carmichael away from long time sponsor Kawasaki. |

In 1996 the MX press could not wait to get their hands on the all-new machine. Early tests sugarcoated the bike somewhat, calling its ridiculously ridged chassis “pro oriented” and awesome for Supercross. In reality, the Honda was an overbuilt beast that transmitted every pebble on the track directly to the rider’s hands. Honda made certain the alloy frame was not going to break, but they ruined the rest of the bike in the process. The beefy frame acted like a big tuning fork, funneling every ounce of vibration from the motor right up through the CR’s handlebars. On hardpack soil the CR was unsettled and never felt firmly planted to the track. In deep loam, the bike performed better and felt more at home. Turning was typical mid-nineties Honda, sharp in the tight sections and nervous at speed. In addition to being unforgiving, the harsh frame gave the bike a “dead” feel in the bumps. Instead of floating over obstacles, the “97 CR250R “thudded” through them. The CR’s chassis may have looked high tech, but its performance was strictly mid-evil in ’97.

|

|

In 1997 Honda switched back to Showa forks after two years on Kayaba’s. The new 47mm Show’s used a version of the new twin-chamber cartridge design pioneered on the ’94 RM250. Unfortunately for Honda, they worked about 50% as well as the Suzuki’s forks. Undersprung and harsh, they hung down in the stroke and battered your hands on every bump. |

Certainly not helping the CR’s brutal chassis was its questionable suspension. For ’97 Honda switched back to Showa components, after 2 years using Kayaba’s on their deuce-and-a-half. The new 47mm forks featured Showa’s twin-chamber internals first debuted on the 1994 Suzuki RM250. While the twin-chambers were awesome performers on the Suzuki, Honda once again found a way to deliver a set of crappy forks to the masses. The stock Showa’s were undersprung out of the crate and poorly set up. They hung down in the stroke and gave the bike a stinkbug stance on the track. If you upgraded the springs, the ride could be leveled out, but the performance remained harsh on anything smaller than a Supercross whoops. When you combined the punishing forks with the rigid chassis, you had a recipe for premature arm pump and very sore hands.

|

|

The rear shock on the ’97 CR was a perfect match to the rest of the bike, hard and unyielding. While this was the first year for the high and low speed compression adjuster on the CR, no amount of tinkering could smooth out its punishing ride. On big landings and hard hits it worked well, but on hard, slippery circuits and choppy bumps, it would not take a set. Braking and acceleration bumps in particular were transmitted directly to your spine as the unforgiving shock hacked and hopped all over the track. |

Much like their forks, Honda had struggled with their shocks throughout most of the nineties. Typically they were better in performance than the gruesome forks, but far from good. For ’97, Showa added both high and low speed adjustments to their shock for the first time. This addeda layer of adjustabilitythat probably confused more riders than it helped, but for pros that could use it was a welcome addition. Performance wise, the Showa shock was much better at big hits than small chop. On tracks with big whoops and deep dirt it worked pretty well. On hardpack surfaces and on small sharp impacts like braking bumps, the shock tended to deflect and ricochet all over the track. If you could get something to hook up to, the shock was passible, if the track was slippery and choppy, you were in for quite a wild ride.

|

|

1997 was a tough year for Honda on the track. After a decade of domination, the loss of McGrath left them without any real shot at a MX/SX title. Ironically, their only win of the year would come at the hands of longtime Yamaha rival Damon Bradshaw. After a falling out with Team Yamaha at the end of ’96, the Beast from the East would campaign an AXO backed Manchester Honda in 1997. While he was at this point, a mere shadow of his old wild self, Damon still had enough left in the tank to capture a hugely popular win at the rain soaked High Point National. It would be the last win of Damon’s illustrious career. Damon made the decision to ride Honda’s after getting on a ’96 CR250 and loving it. He even won a SX in Japan on the ’96 versus all the top guys. Then the aluminum framed machine came out and he struggled more than expected. |

While Honda struggled mightily with suspension performance throughout the nineties, the one think they had dialed was motor performance. Starting in 1986, Honda pretty much had the motor category on lockdown. Year in and year out, nothing was as fast as a Honda CR250R. For ’97, Honda made a lot of changes to their tried and true mill. They lowered the deck height, went to a flat-top piston, reshaped the HPP valve and bolted on an all-new exhaust pipe. In addition to the internal motor modifications, Honda added a revised ignition (featuring an early version of traction control) and an all-new “powerjet” carb. The powerjet was big news for ’97 and it promised to fill in the dead spots in the CR’s powerband by delivering extra fuel at just the precise moment based on engine RPM and load.

|

|

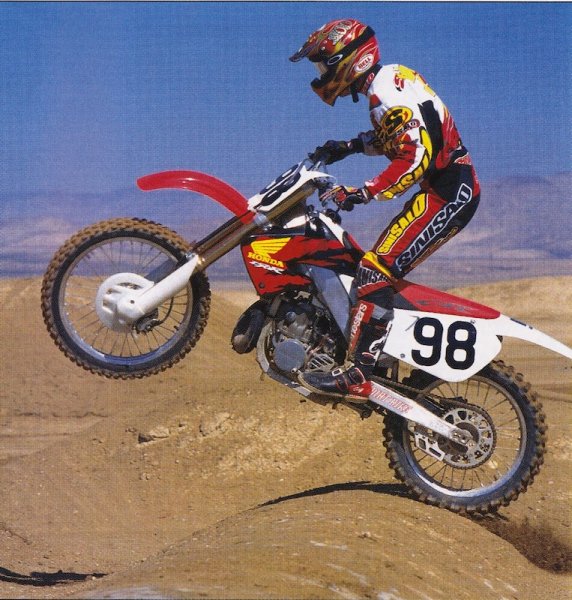

Here Mike Kiedrowski demonstrates the proper technique to make the ’97 CR250R work. Damn the torpedoes full speed ahead! The Four time National motocross champ made a stab at a comeback in 1997 aboard a Honda of Troy CR250R. To say the season did not go well would be a massive understatement, as the MX Kied spent much of it on the sidelines with injuries. It is hard to say if he would have done better on a different machine, but it is pretty clear the new Honda was far from the best bike on the track in ’97. |

All the changes added up to another Honda rocketship for ’97. The new CR250R lacked some of the low-end torque of its predecessors, but gave up nothing from mid-range on up. After you pulled past the lethargic bottom end, the CR lit the afterburners with a meaty mid-range blast and quasar top-end pull. With its soft low-end and hard-hitting mid-range, the CR could be a handful on slippery tracks, but if there was traction, nothing could run with the Honda 250. Top-end power in particular was unchallenged in ’97, as the CR pulled harder and farther than any other quarter liter machine. Some riders preferred the ’93-’96 CR’s wider power spread, but no one could deny it was fast. The ’97 CR250R was not mellow or easy-to-ride, but it would show any other bike its rear fender in the race to the first turn.

|

|

One interesting feature on the 1997 Honda CR250R was its massive single radiator. Not seen on a motocross bike since the early 80’s RM125’s, the big radiator was said to provide 50% more cooling area for the machine. It must not have been that great of an idea, because Honda would drop it and go back to a more conventional dual radiator set up with the second generation frame in 2000. |

As with any Honda built since the early eighties, build quality was excellent. All the parts fit perfectly and nothingfell off unexpectedly. Early durability concerns about the aluminum frame proved unfounded as well, as the new chassis proved even more durable that the old steel frame had been. Brakes were also a high point, as the Honda’s Nissin binders proved both the most powerful and least in need of maintenance. One area that was a point of contention was the new CR’s sleek new seat. At this point we were just transitioning to the super hard, low profile seats common today and many riders lamented the loss of the older thick seat’s bump isolation. Certainly this only compounded the CR’s general feel of harshness and added to its unforgiving nature.

|

|

So what did your hard earned $5699 get you in 1997? Well, you certainly got the most high tech looking bike on the track. You also bought yourself the fastest 250 by far. Unfortunately, you also got the most tiring machine by a wide margin. The CR’s combination of hand numbing vibration, pummeling ride and explosive power, made the ’97 CR an exercise in pain management. Even for fast pros, the 97 CR250R was a real handful. It was a perfect example of a bike released only half-baked. If Honda had given it a bit more R&D time they probably could have sorted it out, as the very good second generation alloy CR’s pointed out. As it was, it was a bit too much too soon. |

The 1997 Honda CR250R is an interesting machine. It was an incredible sales success, based mostly on its radical good looks and promise of game changing technology. While there is no denying its significance to the history of motorcycle design, the cold hard truth is it was not a very good bike. It was controversial enough to cause the King of SX to walk away from a lucrative long term contract, but also influential enough to steer motocross design for more than a decade. When you look at the machines from any of the Big Four Japanese manufacturers today, it is hard to see the DNA of the 97 CR250R in there somewhere. Honda was first to take the plunge, and they suffered wounds that come with operating on the bleeding edge of design. Even so, they persevered, and within a few years they were building some of the best handling bikes on the track. The 1997 Honda CR250R may not have lived up to all the hype, but damn, it was one badass looking machine.