For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Cannondale’s 2001 MX400.

Today, the name Cannondale is almost a punchline within the motocross industry. A longtime powerhouse in the world of mountain biking, Cannondale’s attempt to break into motocross captured a huge about of the industry’s mindshare in the late nineties. Their proposed aluminum-framed four-stroke looked like just the type of innovative machine that could finally bring an American-made bike into the motocross mainstream. Forward-thinking, unique, and backed by one of the most well-respected names in the cycling industry, the Cannondale Motocross project was the great American hope of late nineties motocross.

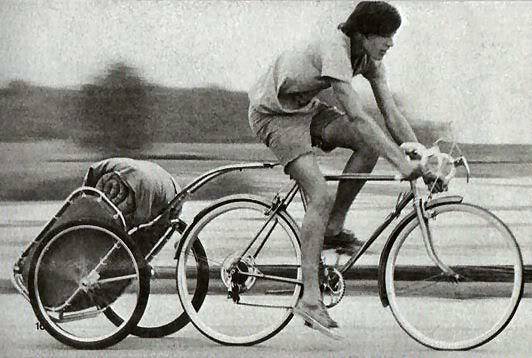

Cannondale’s breakthrough product was the “Bugger” cycle trailer which took the cycling world industry by storm in the early 1970s. Photo Credit: Cannondale

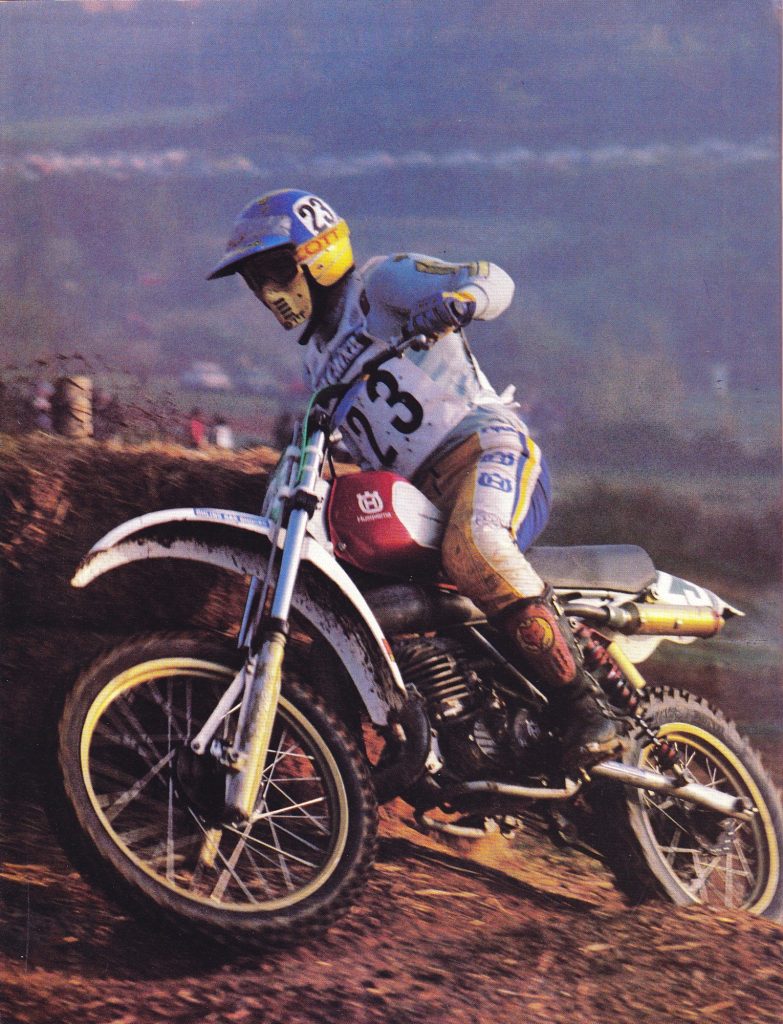

In the 1980s, Horst Leitner’s ATK became the first American-built motocross manufacturer to enjoy some level of success in the market. Photo Credit: ATK

While Cannondale’s motocross project elicited mountains of ink and countless press releases in the late nineties, it was far from the first attempt by an American manufacturer to break into the cutthroat world of motocross racing. In the seventies, there had been efforts by quirky off-road manufacturer Rokon and street bike powerhouse Harley-Davidson that both went astray. America’s first motocross champion Gary Jones even made a go of it with his ill-fated AMMEX machines. Production hurdles, development costs, and relentless competition from Japan doomed all of these nascent operations to failure before they could make any real dent in the motocross market.

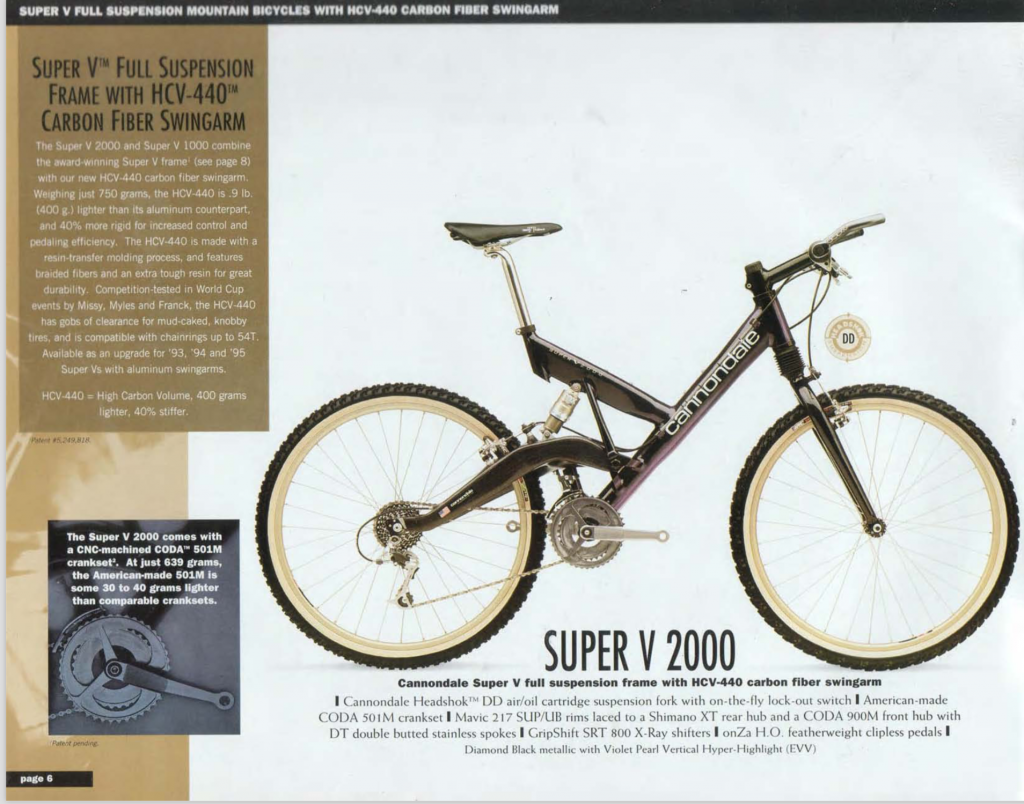

In 1983 Cannondale started building cycles, and by the mid-nineties, they had become one of the most well-respected names in cycling. Groundbreaking cycles like the Super-V mountain bikes helped show they were willing to push the envelope in both construction and design. Photo Credit: Cannondale

In the 1980s, Horst Leitner’s ATK became the only real example of modern American motocross success with its lineup of unique and innovative machines. Using Austrian-built Rotax motors housed in specially-built frames, the ATKs of the late eighties and early nineties became status symbols for well-heeled riders looking for something out of the ordinary. By ignoring conventional wisdom and pushing the envelopes of traditional design, ATK was able to carve out a successful niche within the motocross industry. No other machine on the planet was quite like an ATK and people were willing to pay a premium for the unique vision of Leitner and his team.

While similar in appearance to Honda’s first-generation alloy frame, the design employed on the MX400 was actually quite different. With its large removable lower frame sections and a “no-link” rear suspension system, the Cannondale was a very unique machine. Photo Credit: Cannondale

While Leitner was busy reinventing the modern four-stroke racer, a small team from Connecticut was doing something very similar to the cycling industry. Founded in 1971 by Joe Montgomery and Murdock MacGregor as a precast concrete business, Cannondale stands as one of the true American success stories of the 1970s. After adding partners Jim Catrambone, John Wistrand, and Ron Davis, Cannondale transitioned to selling cycling accessories and camping equipment. This turned out to be the right move for the business as Cannondale’s innovative new cycle trailer and line of accessory bags took the industry by storm. By 1974, they were the industry leader in cycling-related baggage and by 1977, they had expanded enough to need a new factory in Bedford, Pennsylvania.

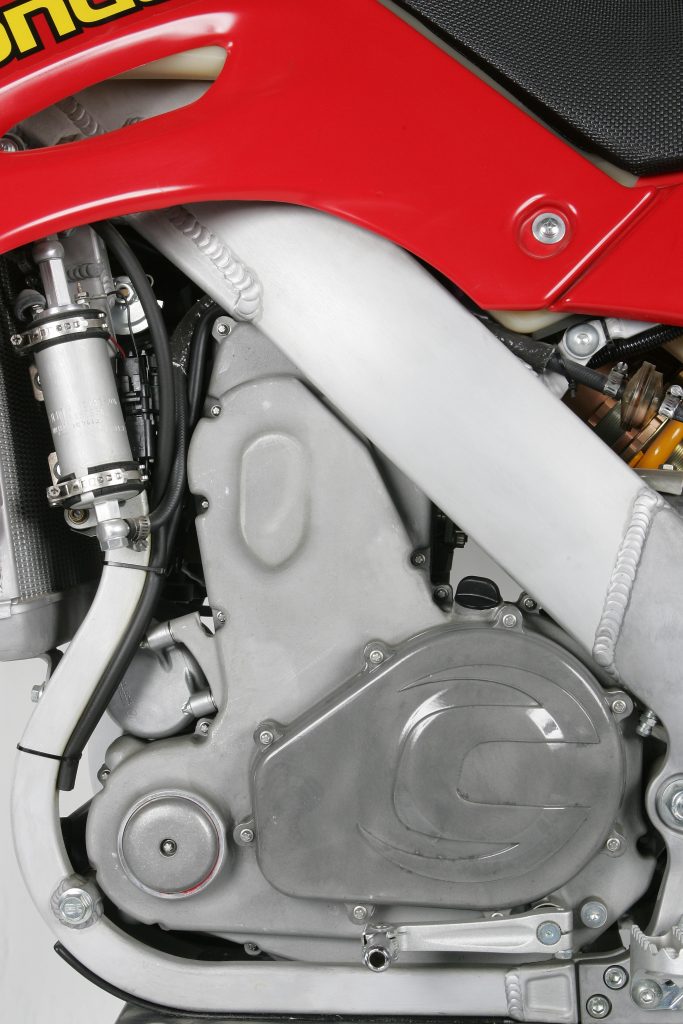

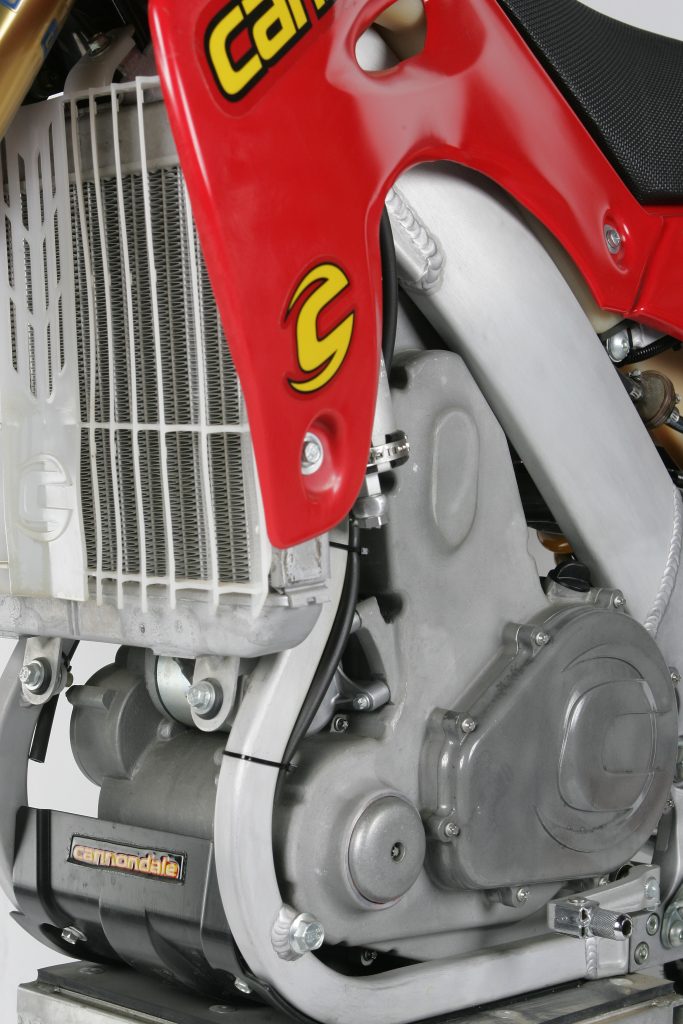

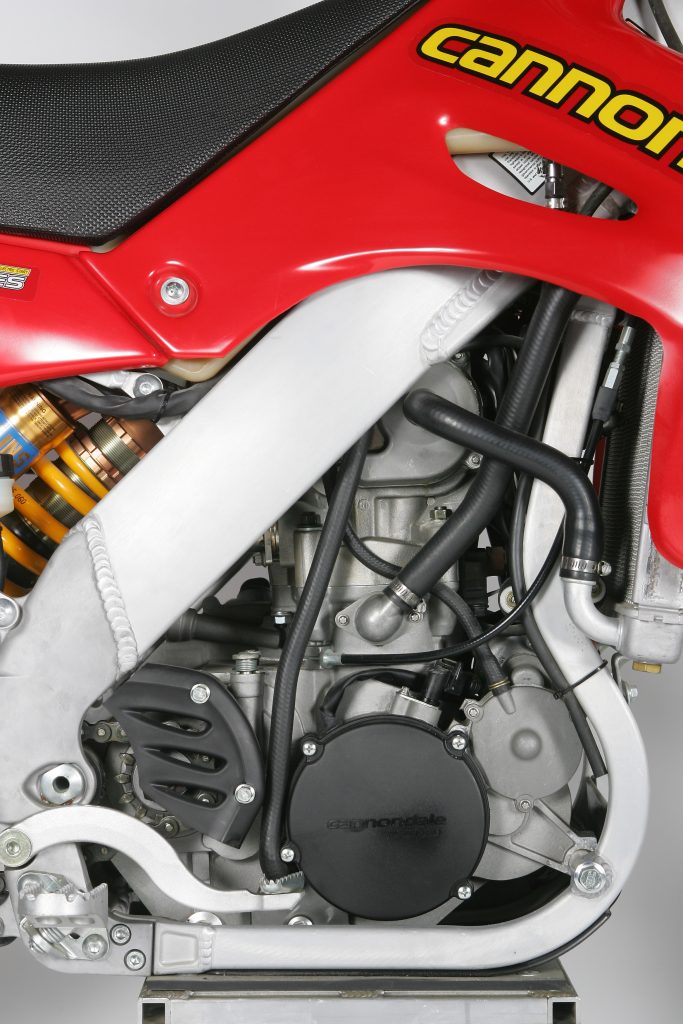

The motor in the Cannondale MX400 was unique within the off-road world in 2001. With its reversed cylinder, fuel injection, electric start, and cassette transmission, it certainly did not lack for innovation. Unfortunately, however, its execution was not nearly as remarkable as its ambitious design. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The motor in the Cannondale MX400 was unique within the off-road world in 2001. With its reversed cylinder, fuel injection, electric start, and cassette transmission, it certainly did not lack for innovation. Unfortunately, however, its execution was not nearly as remarkable as its ambitious design. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

By the early eighties, Cannondale was looking to broaden their business even further and brought on a talented designer by the name of Todd Patterson. Todd was skilled in working with aluminum and helped Cannondale develop a bicycle frame crafted out of the lightweight material. At a time, steel was still the predominant frame material in cycling and Cannondale’s new frame offered superior strength and reduced weight. Launched in 1983, the Cannondale ST-500 was a revolution in the industry. A year later, they followed that up with their first mountain bike, the SM400. Light, strong, and incredibly trick, the Cannondale bicycles were an instant hit.

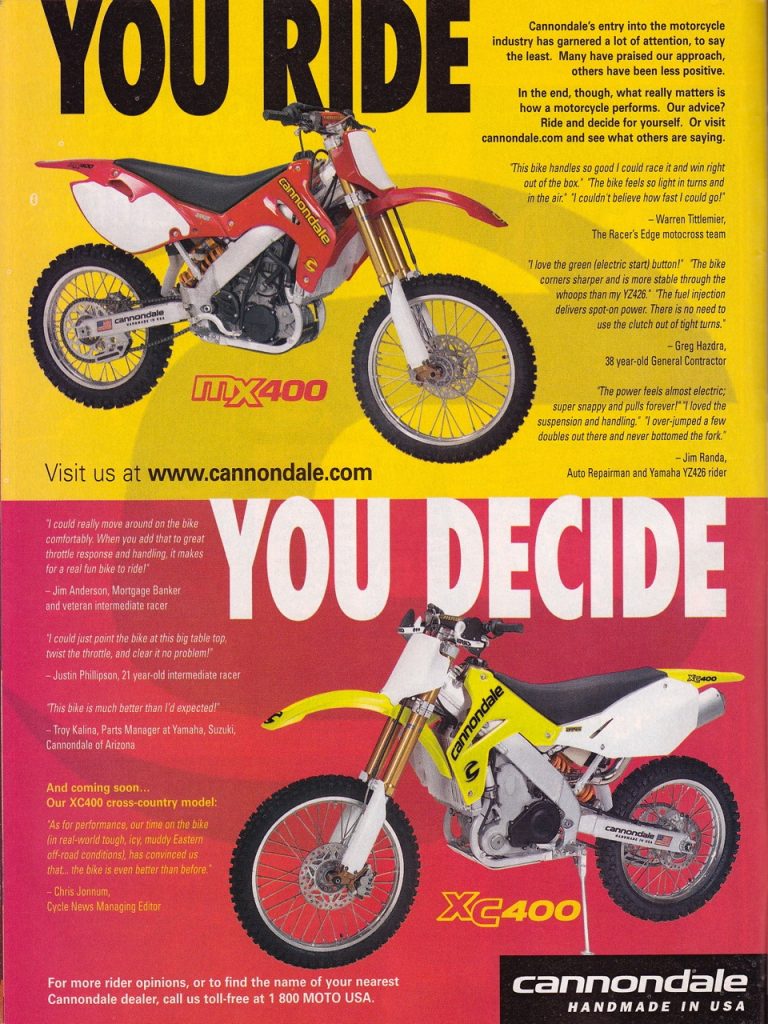

After more than a year of delays the Cannondale motorcycle project made its debut in 2001 with a lineup of motocross and off-road offerings.

Over the next fifteen years, Cannondale would continue to innovate within the cycling industry and grow into one of the most respected brands in the sport. Pioneering designs like the Super V frame and Headshock suspension pointed to a company led by bold people who were not afraid to take chances and blaze their own trail. With record sales, international success, and a slew of world titles to their name, the upstart bicycle builder from Connecticut looked like they could do no wrong.

When the Cannondale motocross project was announced in 1998 the market for a high-end four-stroke racer seemed wide open. Yamaha’s YZ400F was proving to be an enormous hit and riders were clamoring for Open-class machines with modern ergonomics and a more civil nature than the old 500cc two-strokes. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1997, the motocross landscape was at a bit of a crossroads. While still dominated by two-strokes, the announcement of Yamaha’s revolutionary YZ400F had rekindled interest in the once-overlooked thumper. Doug Henry’s win in Las Vegas on the prototype YZM400F and a slew of overseas championships by riders like Joël Smets and Jacky Martens had many thinking the future of the Open class was valve and cam. By this point, all of the Japanese had abandoned the development of their big-bore two strokes which left the market wide open for someone to disrupt the status quo. With the introduction of the YZ400F, it looked like Yamaha might be that disruptive force, but Cannondale had other plans in mind.

With bodywork by Cycra and a motor based on an existing Husaberg design, early Cannondale prototypes looked fairly conventional. Photo Credit: Motocross Journal

At first glance, Cannondale’s move into the motocross market might have seemed like a surprising one , but they were gambling that their experience with aluminum chassis design was just the ace in the hole they needed to carve out a piece of the red-hot four-stroke market. In 1997, Honda had introduced the world to the first mainstream aluminum motocross chassis. The all-new aluminum-framed CR250R garnered huge sales based on its looks alone. It appeared to be a bike from ten years into the future and riders snapped them up in droves. Seeing the success of the aluminum CR and the incredible anticipation surrounding the YZ400F, the temptation to disrupt yet another industry was too much for Cannondale to resist.

Early production targets had Cannondale shooting to undercut the YZ400F’s weight by as much as 15 pounds. Unfortunately, once they ditched the Swedish-designed motor and started adding features, that weight figure ballooned considerably. Photo Credit: Motocross Journal

Early production targets had Cannondale shooting to undercut the YZ400F’s weight by as much as 15 pounds. Unfortunately, once they ditched the Swedish-designed motor and started adding features, that weight figure ballooned considerably. Photo Credit: Motocross Journal

When the MX400 project was started in 1997, Cannondale entered into it with some very lofty goals. They were not just interested in building a competitive American race bike, they aimed to advance the art of motorcycle design. Relying on their extensive knowledge in aluminum frame construction, the new machine was slated to employ a lightweight alloy frame and feature the very latest in chassis design. For the power plant, Cannondale chose to follow Yamaha’s lead and feature a four-stroke configuration. This would make the bike more complicated and costly to produce but would be in keeping with its status as a premium Open class machine. Without an in-house motor department available, Cannondale looked to the Swedish firm Folan to develop its new motor. To give the bike a unique look, Cannondale reached out to plastic manufacturer Cycra who crafted sleek new bodywork for the prototype. For the suspension, Cannondale contacted Kayaba, Fox Factory, and Öhlins to submit components they could test. Like ATKs from a decade before, the new Cannondale was slated to be built without a linkage so proper shock setup would be critical to the new machine’s performance.

Long-time GP competitor Mike Guerra was brought onboard in 1997 to head Cannondale’s ambitious motocross project. Photo Credit Motocross Action

Overseeing all of these many separate departments was former Husqvarna factory rider Mike Guerra. A long-time GP competitor, Mike had finished an impressive sixth overall in the 1981 and 1982 250 World Championships. After retiring from racing, Guerra worked as a project manager for Koni Shocks and Volvo of Sweden before moving to Cannondale in 1997. With both racing know-how and corporate management skills on his resume, Mike seemed like the perfect person to oversee the fledgling project.

The Cannondale’s motor pumped out a mellow spread of power from its 432cc. It was soft down low and made its best power in the midrange. Compared to the ground-pounding YZ426F and ultra-smooth KTM 520SX, the MX400 was down on power at every point in the curve. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Initially, the most innovative component of the Cannondale was its frame. In 1998 when the bike was officially announced, only Honda was offering any sort of alloy chassis on an off-road machine. While similar in its perimeter configuration, the Cannondale version was unique with a set of front downtubes that could be removed to access the motor or be replaced if damaged. Aside from this and its no-link rear suspension, the Cannondale prototype seemed highly conventional. Early motor designs were reported to displace 408cc and the engine was largely based on existing Husqvarna and Husaberg designs. As the project moved forward, however, the Cannondale team started to break new ground in several areas.

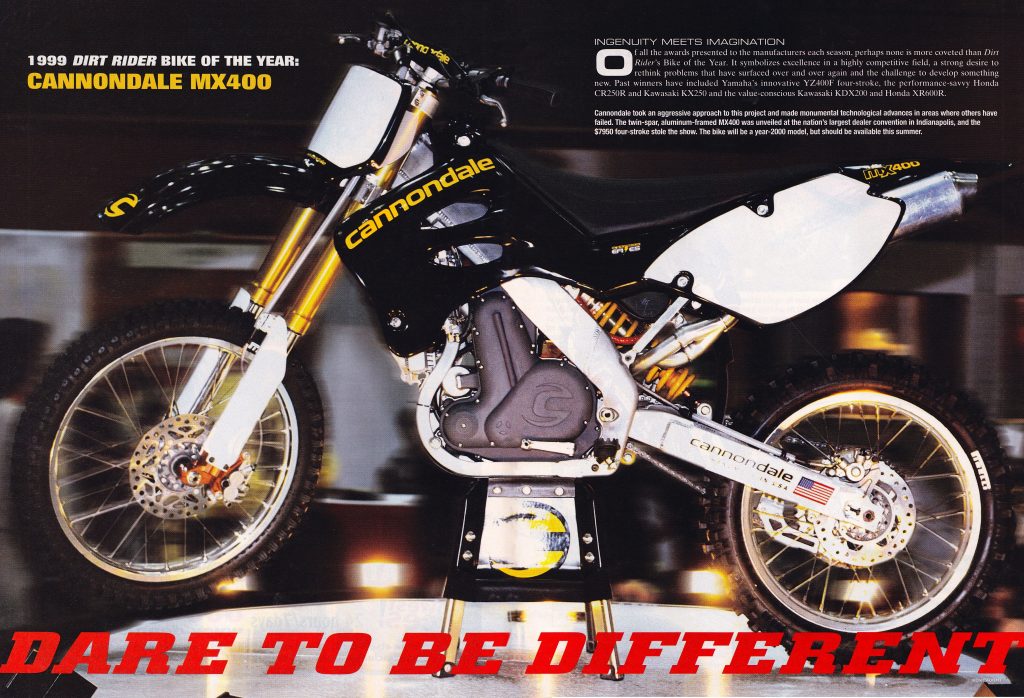

With the engineering might of Cannondale behind it, more than a few people thought the new MX400 was a sure bet for success. Dirt Rider went as far as to proclaim the Cannondale the Bike of the Year in 1999 based solely on the hype generated for the machine. Unfortunately, for everyone involved, the real bike was never able to live up to all those expectations. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

With the engineering might of Cannondale behind it, more than a few people thought the new MX400 was a sure bet for success. Dirt Rider went as far as to proclaim the Cannondale the Bike of the Year in 1999 based solely on the hype generated for the machine. Unfortunately, for everyone involved, the real bike was never able to live up to all those expectations. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

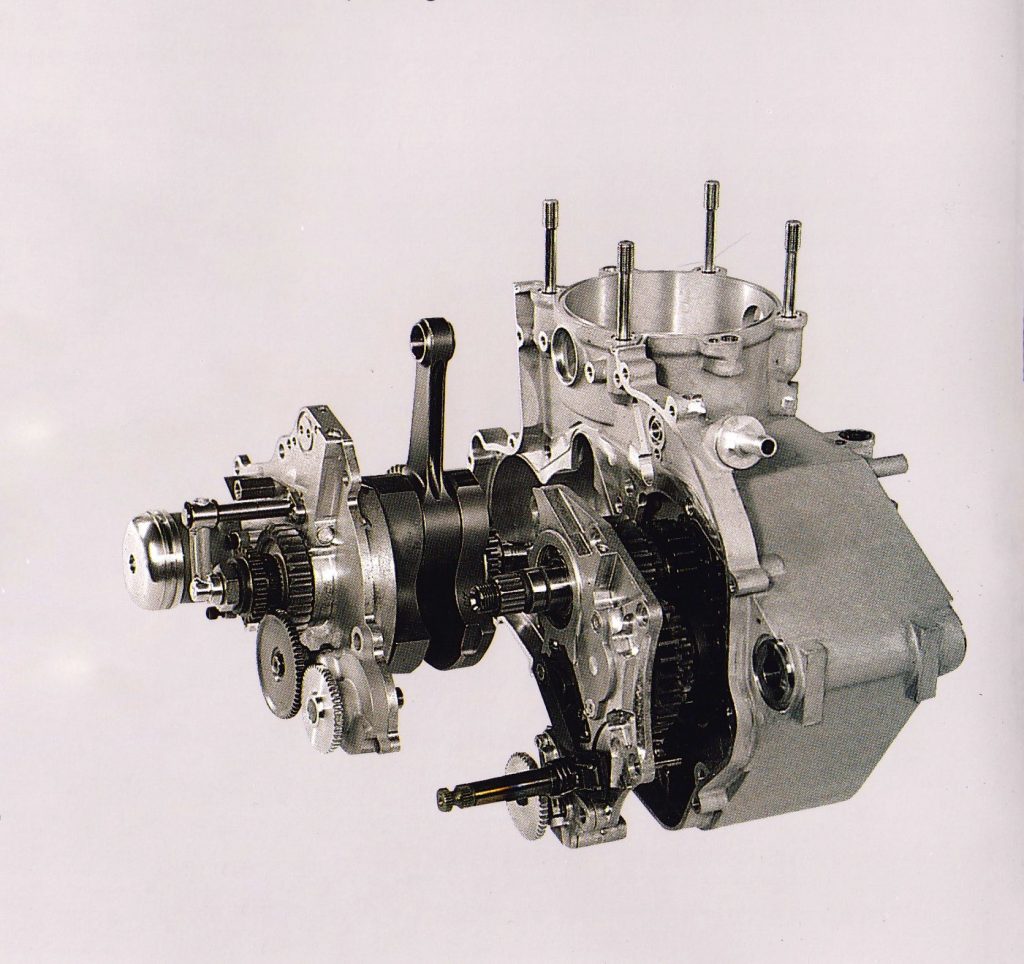

By the time 1999 rolled around the Cannondale design team had made several changes that would prove fateful to the eventual success of the Cannondale motocross project. After testing several versions of the Folan motor, the engineers decided they wanted to go their own way and scrap that design entirely. Dropping Folan, Cannondale commissioned a North Carolina-based NASCAR engine builder to help them design an all-new engine. Instead of a traditional design based on a Swedish template, the reimagined Cannondale engine broke new ground by reversing the cylinder layout and using a completely new case design.

Once released, the production Cannondales were available in red or this handsome black edition. Aside from their rather odd-looking motors, these early MX400s were handsome machines. Photo Credit: Cannondale

The new motor bumped up the displacement to 432cc and featured a four-valve dual-overhead-cam design. With the cylinder reversed, the intake was moved to the front and the exhaust outlet was moved to the back. According to Cannondale, this was done to reposition the cylinder for better weight distribution, provide a straighter intake tract for increased power, and shorten the exhaust pipe for reduced weight and stronger top-end performance. The lower cases were unique as well and featured a one-piece design that allowed the crank and transmission to be removed without splitting them in a traditional fashion. The transmission was a five-speed “cassette” style that could be removed as a complete unit. To prevent contamination from the clutch infiltrating into the top end, the new motor featured separate oil chambers with the bulk of the top end’s oil housed within one of the frame’s large aluminum spars. Finishing off the motor package was an electric starter and an all-new Sagem fuel injection system.

One unique feature of the new MX400 motor was its case design, which allowed the crank and transmission to be removed without splitting the cases. Photo Credit Cannondale

Going into this project, Cannondale had estimated the development and marketing costs of the MX400 would total somewhere in the range of $20,000,000. Certainly no small amount of money, but well below the $100,000,000 price tag some industry insiders had warned might be the real cost to bring an all-new machine to market. If they had stuck to a more conventional design, their initial estimates may have been attainable, but as they continued to innovate, those costs skyrocketed. Delay after delay met the design team as they tried to work out the many issues that cropped up as the project evolved.

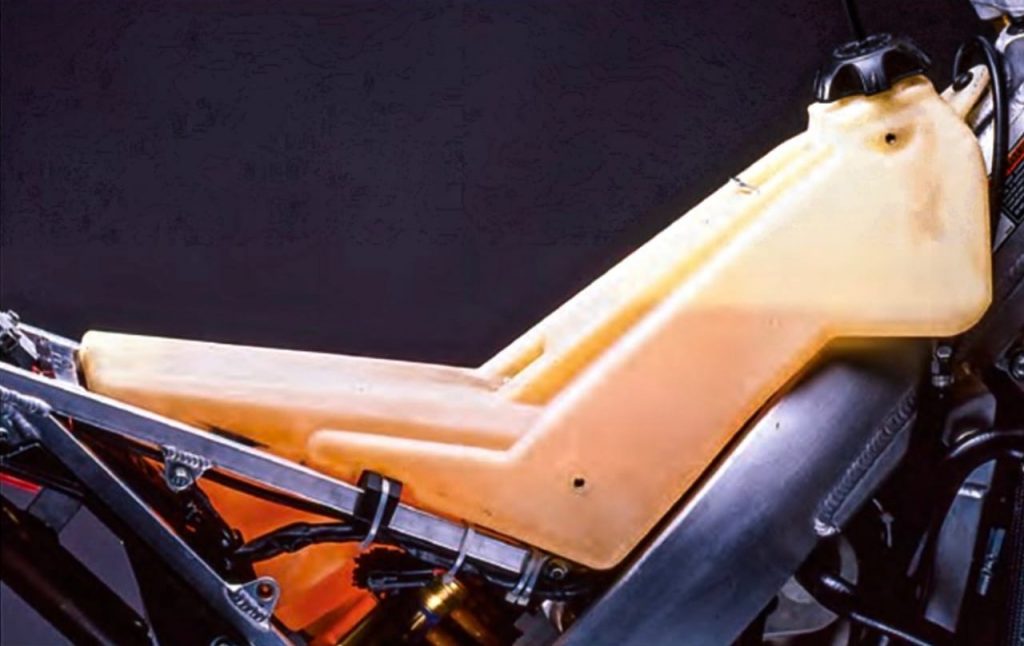

One of the early decisions the team made was to place the air filter up high behind the front number plate. This was done to allow the motor to draw in clean and cool air, thus providing more power. While this thinking was sound in the theory, it turned out to be far more difficult to implement in practice. Unlike the current Yamahas, which place their airbox directly on top of the motor’s intake, the original Cannondale design had to channel air through a hollow passage in the frame. Because of strength and size limitations, there were limits to how large this passage could be and Cannondale’s engineers quickly realized this single opening could not provide the motor with enough air to perform properly. Eventually, the answer turned out to be a second air filter below the tank. While this helped alleviate the breathing issue, it exponentially added to the maintenance hassles on the machine. To clean the secondary filter, all of the upper bodywork and tank had to be removed and if you did not purchase Cannondale’s special airbox cover, you were assured to soak the secondary filter when washing the machine.

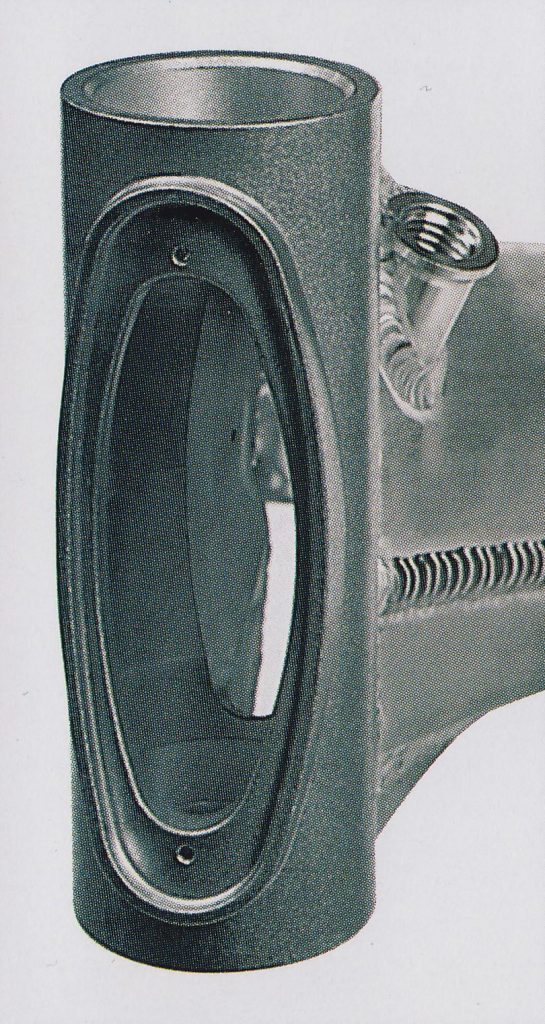

One issue that cropped up on the Cannondale was the motor’s inability to draw enough air through this passage in the frame. By mounting the air cleaner behind the front number plate Cannondale believed they would be able to provide the motor with more clean and cool air but instead they ended up creating a choke point that was not easy to overcome. Once the steering stem was installed there was just not a lot of room left in there for air to pass through. Photo Credit: Cannondale

On the exhaust side, the outlook was not much better. Initially, Cannondale touted the shorter exhaust routing as a plus to the machine, but as Yamaha would learn a decade later, cutting your header pipe in half is not conducive to making broad four-stroke power. Yamaha’s answer in 2010 was a unique “tornado” header pipe that packed a lot of header into a small area. On the Cannondale, the engineers did not seem to foresee this possible issue and as a result, the MX400’s motor never quite lived up to its full potential.

Cannondale’s work-around to this air problem was to add a secondary filter below the fuel tank. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In late 2000, the first Cannondale MX400s started making their way to magazine testers. After nearly two years of delays, Cannondale was desperate to get the bikes to dealers and get the word out that the machines were finally becoming available. When the MX400 project had been started, the YZ400F was not even in production yet, but by the time the bike finally hit dealers in 2001, the YZF was already on its second generation and KTM’s excellent 520SX was stealing headlines of its own. With the prospect of Honda’s CRF450R on the horizon, the Cannondale’s competition had gone from nearly non-existent to brutally cutthroat. When you added in its unproven track record and much steeper opening price of nearly $8000 (a YZ426F cost $5999 in 2001), the way forward for Cannondale’s motocross project looked to be a difficult one.

On the track, the Cannondale’s motor did its best work in the midrange. It was reasonably powerful when in its sweet spot but there was not a lot of usable thrust above or below this midrange surge. Photo Credit: Cannondale

In the end, if the MX400 had turned out to be a world-beater on the track, most of these potential setbacks would have been forgotten. People love convenience and are willing to live with a little extra weight and a bit higher price if it feels like the value is there. ATK 605s were heavy and pricy beasts, but people happily snapped them up as fast as ATK could turn them out. By 2001 of course, the four-stroke bullseye had moved appreciably, but if Cannondale had been able to offer the same high-performance, exclusivity, and quality as ATK had a decade before, the MX400 might have turned out to be a hit despite its unconventional design and many teething issues. Alas, however, this was not to be.

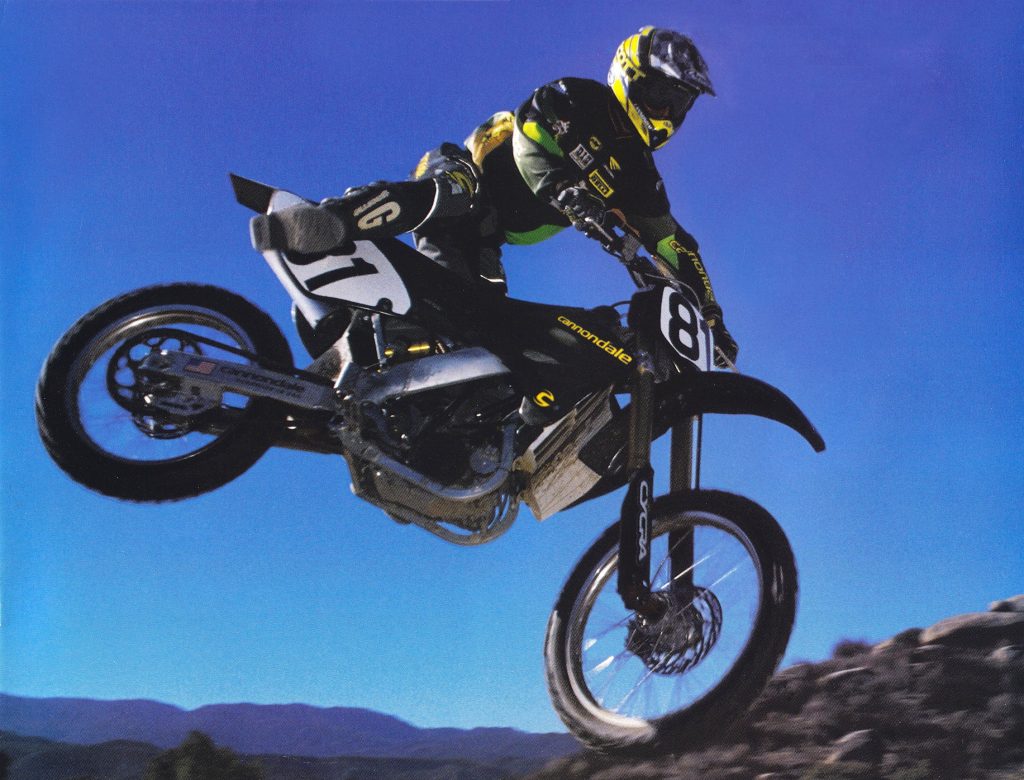

In the air or on the ground you felt every one of the Cannondale’s 260 pounds. Photo Credit: Cannondale

Once magazine testers got their hands on the new machine it became very clear that the MX400 was still a work in progress. There were issues with the fuel injection and ignition that caused the MX400 to hiccup and lurch at low-rpm. It also had the annoying habit of flaming out at regular intervals. If you turned up the idle to stop the cough, then the motor revved up like the throttle cable was kinked. If you turned the idle down to stop the motor from racing, then you risked a stall in every slow corner. In addition to being buggy, the fuel injection was also hypersensitive to temperature and humidity changes. Normally, this was one of the big advantages of fuel injection, but on the Cannondale, it turned out to be more persnickety than the carbureted setups found on the competition.

Both the MX400 fuel injection and electric starting systems turned out to be problematic affairs. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Both the MX400 fuel injection and electric starting systems turned out to be problematic affairs. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The electric starter, while convenient, also turned out to be a mixed blessing. Despite its substantial weight penalty, many riders were happy to live with a little extra tonnage to have the magic button. Decades of dealing with hot four-strokes had proven that that starting them in the heat of battle was often their Achilles Heel. By adding an electric starter, Cannondale was able to both solidify its position as a premium offering and allay the fears of many two-stroke converts.

Servicing the MX400’s top end was a complicated affair that required removing the complete motor from the frame.Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Unfortunately, however, the electric start system used on the MX400 turned out to be inadequate for the machine’s intended use. When the motor was cold, it worked as advertised, but once the motor heated up, it struggled to turn the piston over. Even worse, the engineers failed to install a kickstart as a backup, so if the bike flamed out mid-moto your only option was to find a hill to bump-start it. In an $8000 racing motorcycle, this was not ideal.

The Cannondale’s fuel tank carried 2.1 gallons and employed a rather unconventional design. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In terms of actual performance, the Cannondale’s unconventional 432cc motor was a pretty disappointing performer. On the dyno, it pumped out around 43 horsepower which was equivalent to a 250 two-stroke of the time, but well short of the power put out by Yamaha’s YZ426F and KTM’s 520SX. Low-end torque was very shallow for an Open class four-stroke and the bike only came alive over a short duration in the midrange. Above that burst, the motor’s power tapered off appreciably. On the track, the MX400 had to be ridden more like a two-stroke than a big thumper. It lacked the churning torque and heavy vibes of the competition and needed to be revved and shifted constantly to generate competitive speed. There was also a ton of compression braking, which could be useful but put off most two-stroke converts. This was a trait that newer racing thumpers like the YZ-F were trying to lessen but the Cannondale had a much more traditional four-stroke feel.

While not a shredder, the MX400 was a pretty capable handler once the suspension was set up and the chassis was properly balanced. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While not a shredder, the MX400 was a pretty capable handler once the suspension was set up and the chassis was properly balanced. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

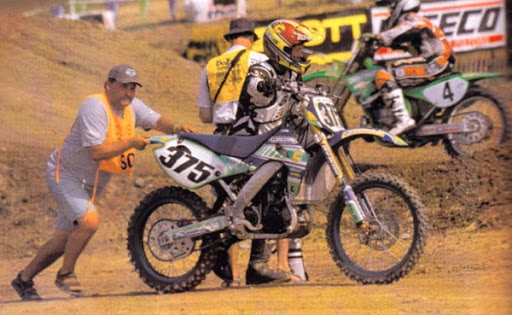

Unfortunately, in addition to not being particularly fast, the new motor turned out to be very unreliable. Virtually all the test bikes given to the magazines suffered catastrophic failures of some kind or another. Top-end malfunctions, faulty electronics, and exploding transmissions were all witnessed by testers. Perhaps even worse were the MX400’s many mishaps during the 2000 AMA Motocross Nationals. Team Cannondale riders Keith Johnson and Jeff Gibson spent the summer pushing pre-production MX400s off to the side of the track as the machines repeatedly broke down. For a brand with no proven track record, these public failures were massive blows to the fledgling brand’s reputation. Before a single Cannondale MX400 was offered for sale, the machine had already developed a very dubious reputation for unreliability.

In 2000, Cannondale made an attempt at the 250 Motocross Nationals with Jeff Gibson and Keith Johnson at the controls. While the purpose of the campaign was to shake down the new bikes, the many very public DNFs the team suffered during the season did the brand no favors in the court of public opinion. Photo Credit: Racer X

Another disappointment turned out to be the bike’s prodigious weight. When Motocross Action spoke to Mike Guerra in 1998, he listed the target weight of the MX400 as 235 pounds. In that interview, Guerra stated that they wanted to undercut the YZ400F by 10-15 pounds. While a lofty goal, this turned out to be a total pipe dream. Their decision to drop the compact Folan design and go with a much larger and heavier electric-start and fuel-injected motor doomed the MX400 to being painfully overweight. By the time the production MX400s started rolling off the assembly lines that target of 235 pounds had ballooned up to an XR-like 260 pounds. That was 21 pounds north of KTM’s 520SX and significantly heftier than the notoriously portly YZ426F.

One area where Cannondale did not skimp was in the suspension department. The MX400 used high-dollar SwedishÖhlins components front and rear. While certainly capable of excellent performance, overly soft settings from the factory held the forks back on the track. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the suspension front, the new Cannondale used premium-quality Swedish Öhlins components front and rear. These were high-dollar units that certainly added to the overall cost of the MX400 but were in line with Cannondale’s aim to position the machine as a premium product. Up front, the engineers settled on Öhlins’ FG9910 front forks which delivered 11.8 inches of travel and offered adjustments for both compression and rebound damping. In the rear, the MX400 followed KTM’s lead by deleting the linkage entirely and bolting on an Öhlins Position Sensitive Damping (PSD) shock. Like the WP KTM version, the Öhlins PSD damper looked to simulate the mechanical advantages of a linkage through careful shock placement and special internal valving. Without an airbox to contend with, the Cannondale engineers were able to lay the MX400’s shock down at an extremely steep angle that was similar to what Yamaha had used on its early monoshock designs.

The new MX400 employed a no-link design and PSD shock which was similar to the KTMs of the time. The Öhlins damper worked better than the forks but was still a step behind the best rear ends available in 2001. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The new MX400 employed a no-link design and PSD shock which was similar to the KTMs of the time. The Öhlins damper worked better than the forks but was still a step behind the best rear ends available in 2001. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the track, the Cannondale’s suspension turned out to be a bit of a mixed bag. The front forks were plush on small impacts but badly undersprung and underdamped for the bike’s weight. Any sort of moderate jump or large whoop used up all of the fork’s travel and the bike dove badly under braking. It was adequate for trail riding but almost unusable on a motocross course. With a fast rider on board, the fork bottomed constantly and struggled to stay up in the travel. If you intended to race the MX400, an upgrade in springs and a re-valve was a must.

The web of hoses, wires, and lines on the right side of the motor lent the Cannondale a very unfinished appearance. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In the rear, the suspension was more effective but far from perfect. At the time, the no-link suspension system seemed to offer several advantages. It was lighter, simpler, and less maintenance-intensive than traditional linkage designs. In 2001, Cannondale became the fourth manufacturer to make this move after ATK, Husaberg, and KTM. In terms of performance, the Öhlins shock was a fairly mediocre performer. Unlike the forks, the shock came equipped with an extremely stiff spring, which jacked up the rear end and gave the bike a hunched-forward stance that played havoc with the chassis’ balance. With the stock spring in place, the shock rode high in the travel and put a lot of pressure on the soft front forks. While the shock did not bottom like the forks, its stiff action was not particularly liked by anyone. Once you installed a softer spring, the shock’s feel improved appreciably. The Öhlins damper was fairly comfortable on the small chop and decently absorbent on big hits. There was a bit of a spike in the damping mid-stroke that detracted from its comfort, but it was more raceable than the overly-soft forks. Some riders also complained that the shock offered the same “dead” feeling in the whoops that had plagued KTM’s no-link machines. Off-road, this was actually an advantage, but for motocross, it made the bike “thud” instead of popping off of some obstacles. With a softer spring on the shock and firmer springs up front, the stock suspension’s performance improved immensely. These changes evened out the chassis and were vital to getting the best out of the Cannondale’s handling potential.

Air Beef: Big whips were not in the Cannondale’s arsenal of tricks in 2001. Photo Credit Dirt Bike

Air Beef: Big whips were not in the Cannondale’s arsenal of tricks in 2001. Photo Credit Dirt Bike

After the suspension was sorted, the MX400 could be a decent handler. In stock condition, it dove in the corners and was a handful, but once things were evened out, it worked pretty well for a 260-pound machine. On the ground and in the air, you felt every one of those pounds, but it was reasonably nimble for its size. In the turns its aggressive geometry, heavy engine, and massive compression-braking put a lot of weight on the front wheel. This helped it stick on slick turns but the bike could get ahead of itself if ridden too aggressively. If you tried to attack tight corners like you were on a YZ125 then the big four-stroke was likely to balk and let you know to calm down. If you took your time, though, and used the engine to your advantage, then you could take lines that were not possible on a two-stroke. At speed, the MX400 was super stable and confidence-inspiring. Here, the machine’s mass worked in its favor. It was not easy to knock off its intended course and the bike flew straight and true off of jumps. If you did get a bit out of line, though, it took a good deal of strength to reign the big girl back in. Overall, the Cannondale turned out to be a decent handler despite its portly disposition.

Loaded with ambition and bristling with innovation, the Cannondale MX400 was a machine ahead of its time. Photo Credit: Cannondale

On the detailing front the Cannondale was impressive in some areas but head-scratching in others. Items like the high-dollar Öhlins suspension, plush seat, aluminum bars, great pegs, Nissin brakes, and beautiful alloy welds pointed to the premium aspirations of the brand, but its assortment of oddball fasteners, poorly thought out servicing, and questionable reliability belied a machine not quite ready for prime time. If Cannondale had been able to spend another year or two sorting out the MX400, things might have turned out very differently. Unfortunately, however, by 2001 the brand was hemorrhaging money and had to release an unfinished product. Its original estimate of $20,000,000 had ballooned to nearly $80,000,000 and there was intense pressure to get the MX400 and its off-road variants to market. Bold, pioneering, and incredibly ambitious, the Cannondale motocross project turned out to be a cautionary tale of corporate hubris.

ATK, America’s first motocross success story, became the savior of Cannondale enthusiasts in 2003 with the acquisition of the remains of their motorsports operation. Photo Credit: ATK

In 2003, Cannondale Motorsports filed for bankruptcy protection with ATK eventually purchasing the assets of their motorcycle operation. Thus ended the Cannondale motorcycle experiment; a victim of overreaching ambition, inexperience, and poor timing. Today, many of the features found on the MX400 have been proven worthy with countless victories on the track. Electric start, fuel injection, reversed cylinders, and alloy frames are all accepted by the modern motocross enthusiast. While this does not overlook the mistakes made by the Cannondale team, it does show that their dream of building the ultimate racing four-stroke was a failure of execution, not of ideas.