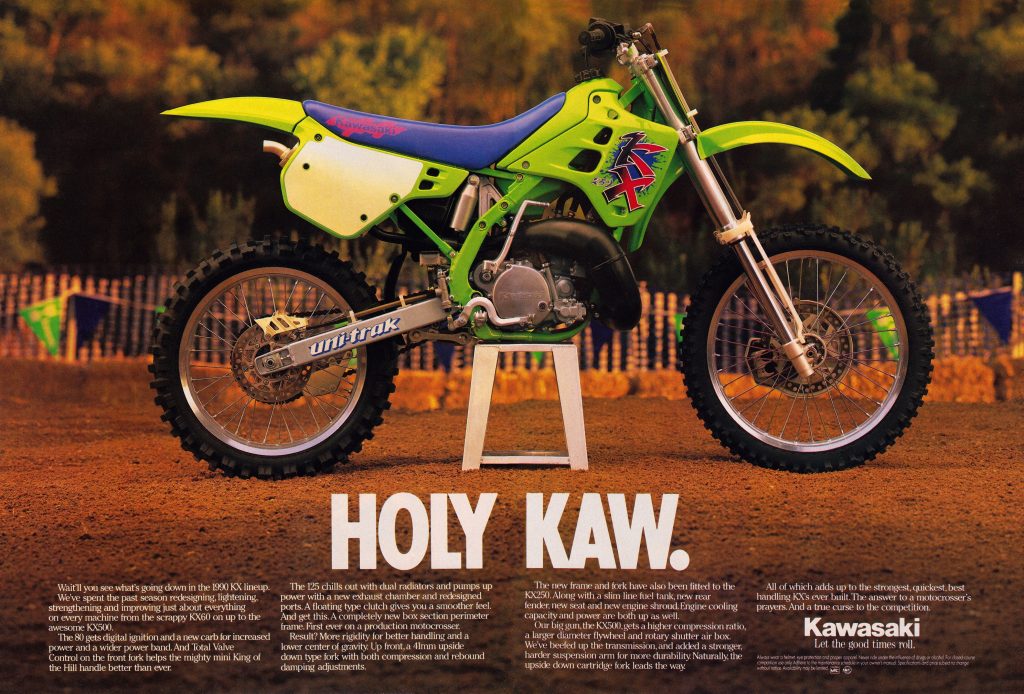

For this week’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at one of the truly iconic machines of the nineties, the 1990 Kawasaki KX250.

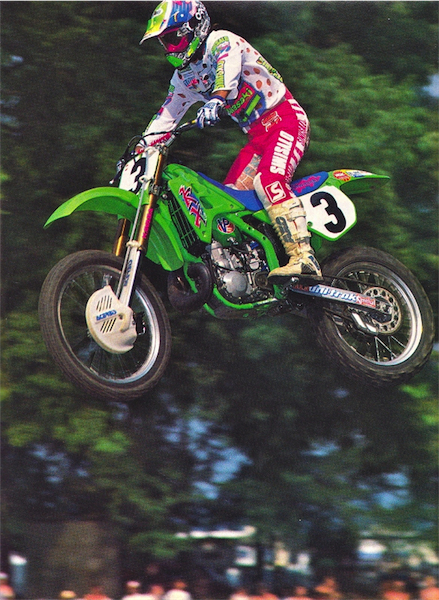

In 1990, this was the absolute trickest machine in motocross. Its road race-inspired chassis and avant-garde styling made the KX the darling of the public and press alike. Photo credit: Kawasaki

Today, Kawasaki is a motocross powerhouse. They build some of the best bikes on the track, field one of the most successful teams, and own a massive wall of number one plates for their trouble. They are the very model of modern motocross success. This, however, was not always the case.

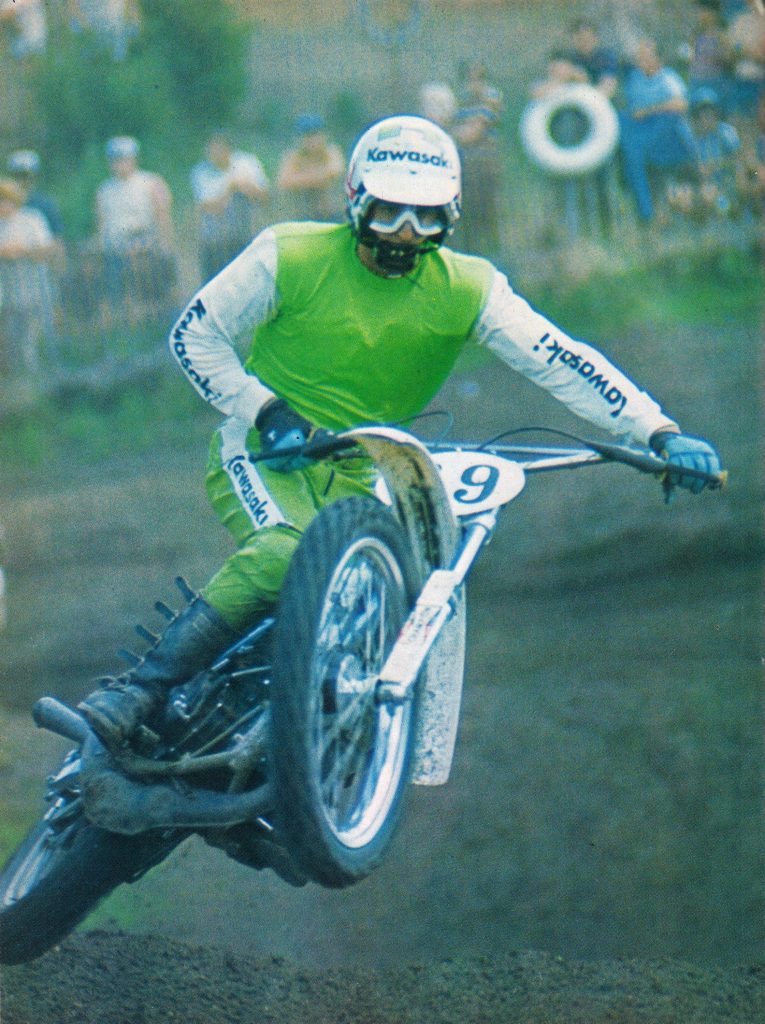

In the early days of Japan’s involvement in motocross Kawasaki was more of a bit player than a serious contender. Early seventies KXs were powerful, but ill-handling and poorly suspended. With lackluster support at the factory and little or no interest at the dealer level, the KXs of the 1970s were often an afterthought to the buying public. In spite of having high-profile riders like Jimmy Weinert, Brad Lackey, and Gary Semics riding green, the Kawasaki brand failed to make much of a dent in Yamaha and Suzuki’s dominant position in the latter part of the decade.

In the seventies, Kawasaki was strictly a bit player in the motocross world. While riders like Jimmy Weinert, Brad Lackey (pictured), and Gary Semics flew the Kawasaki banner on the National stage, very few local riders even had access to the green machines. Photo Credi: Motocross Action

In the early eighties, however, Kawasaki’s fortunes began to change with their renewed commitment to the motocross market. No longer produced in limited numbers, Kawasaki’s motocrossers began to find their way to consumers looking to break out of the yellow mold. Ever improving products in the small-bore classes and a focus on new technology began to win riders over to the green brand. First to market with items like disc brakes and linkage suspension, Kawasaki’s early eighties offerings were quirky but competitive.

Holy Kaw: It is nearly impossible to overstate the amount of excitement this machine generated in 1990. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

By the middle part of the decade, Kawasaki had established itself as the brand to ride in the mini and 125 classes. The KX60, KX80, and KX125 all dominated their classes with powerful motors that easily outclassed their competition. In the 250 class, however, the KX had proven to be a bit of a harder sell. The green deuce-and-a-halves were often plenty fast, but the mediocre suspension and cranky handling that got overlooked in the smaller divisions was hard to turn a blind eye to on the more powerful 250 machines. Stubborn steering and harsh suspension could be ignored when your motor was twice as fast as the next guy, but when all the bikes were fast, these shortcomings became a problem.

|

| For 1990, Kawasaki’s 37.4mm x 70mm 249cc mill produced the most exciting powerband in motocross. It was dead off the line, before exploding in the mid-range with a massive burst of power. It was fast and fun but difficult for less skilled riders to handle. For most racers, the broad and smooth CR250R offered a better motocross powerband. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Don’t forget about Mike Fisher’s Tell Us a Story about developing this bike. Here. |

Toward the latter part of the decade, Kawasaki finally started to get their 250 machines sorted and by 1989, the KX250 was one of the most competitive machines in the class. It offered a powerful motor, workmanlike chassis, and the best forks in the business. Its layout was porky, and its build quality was suspect, but for hard-core racing, it was a very compelling package.

While the Kawasakis of the eighties were not always the best machines, no one could have accused them of fearing to go their own way. Both in terms of engineering and overall design, the KXs were always unique. In 1988, when the motocross world was going slimmer, lower, and leaner, Kawasaki went the opposite direction with a 250 that felt, ran, and weighted like a 500. Big swings, in both styling and design, were never a Kawasaki problem. In 1990, Kawasaki once again blazed its own way by taking its biggest swing yet and introducing the most radical motocross design in a decade.

Even though Kawasaki was often the first to add innovative features like disc brakes and rising-rate linkage rear suspension to their bikes, their 250 machines failed to take off in the eighties. Spotty quality, quirky handling, and “out there” styling did the bike no favors in the market place. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the late eighties, chassis rigidity had become the new motocross buzzword as Supercross had drawn more and more of the manufacturer’s focus. Massive frame tubes, boxed-in pivot points, inverted fork designs were all a result of this quest for less flex. In the street world, a similar search was underway as Universal Japanese Motorcycles of the seventies morphed into the racer replicas of the eighties. There, the engineers found that frames could be made much stronger and more resistant to flex by connecting the steering head directly to the swingarm pivot through the use of two large frame spars. Referred to as a “twin-spar” or “perimeter” design, this new type of frame quickly made its way to ultra-high performance machines like Honda’s VFR Interceptor and Suzuki GSX-R.

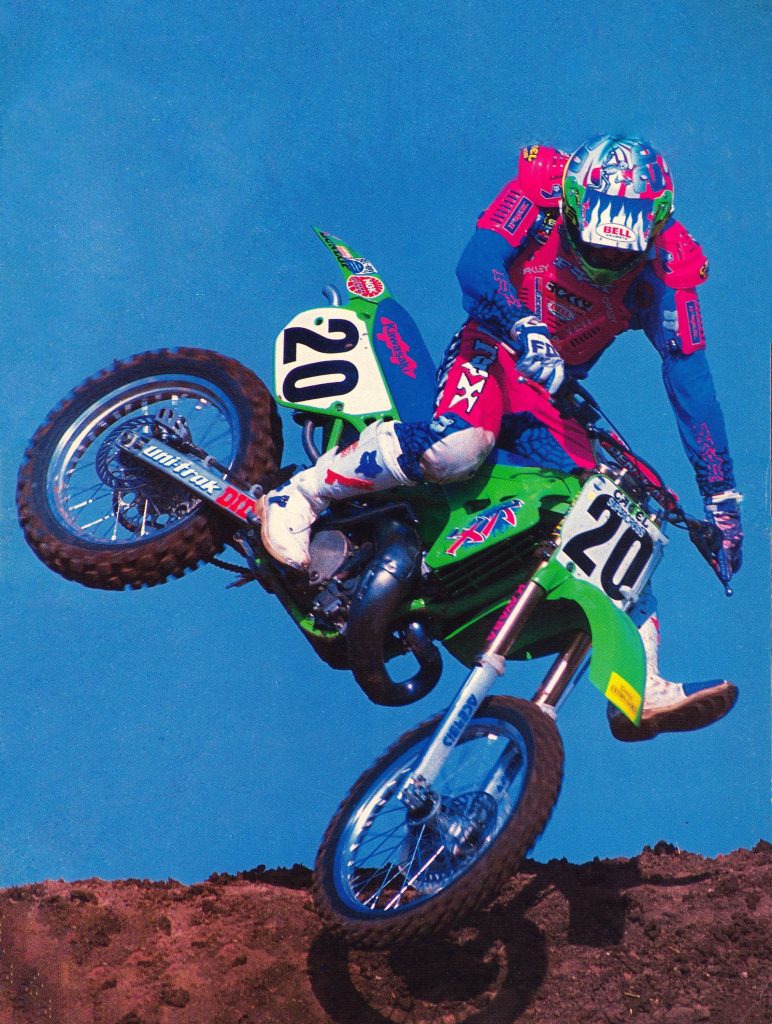

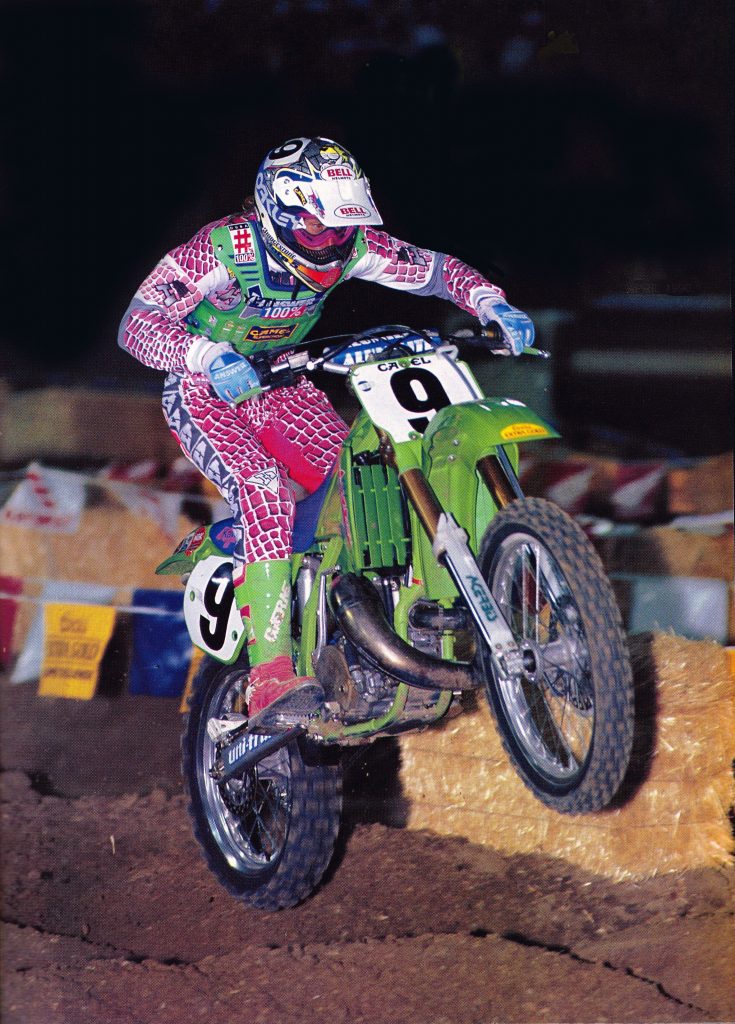

In 1990, Jeff Matiasevich made the jump to the 250s after back-to-back 125 West Coast Supercross titles in ’88 and ’89. Jeff would make an impact immediately on the new KX250, leading races and winning the Las Vegas event. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

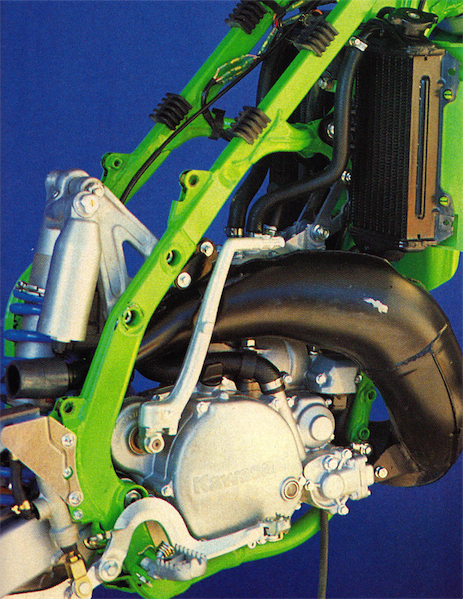

In 1990, Kawasaki took the bold step of bringing this road race technology to the dirt with the introduction of the sport’s first perimeter frame designed for motocross. Crafted out of tough Chromoly steel, Kawasaki’s perimeter frame consisted of two large box-section frame spars arranged in a parallel fashion, which ran from the steering stem to just below the attachment point of the swingarm. Connecting these two large spars were a cross brace in the middle and an additional brace at the base. Unlike most road race perimeter frames, which used the motor as a stressed member, the new Kawasaki motocross design employed a rather conventional single down tube, which split into a double-cradle on the bottom. As with the ‘89 KX, the rear subframe was detachable and crafted out of lightweight aluminum. Where the two really departed was in the mounting of the shock, which was connected to the 1990 frame by two large aluminum hangers. This both saved weight and made servicing easier. Overall geometry on the new frame was significantly more aggressive than 1989 in a bid to improve the old bike’s rather pedestrian turning manners.

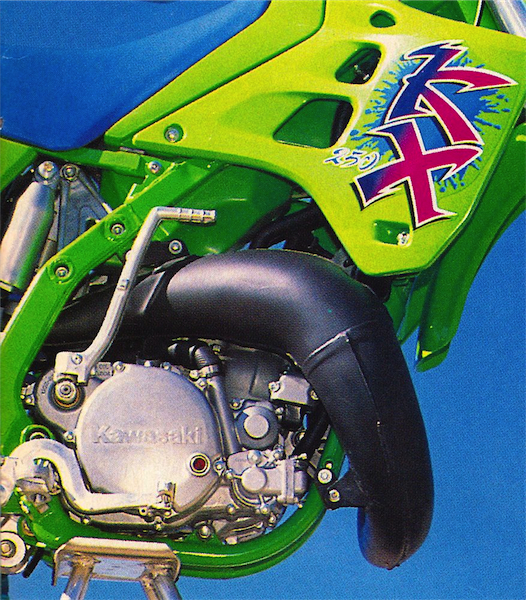

|

| The low down: The 1990 KX250 would be the first Kawasaki to employ a true “low boy” exhaust. This mass-centralizing design had been pioneered by Honda on the ’88 CR250 and would be in use by all the manufacturers by the mid-nineties. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

In addition to an all-new frame, the 1990 KX250 featured completely restyled bodywork that left no doubt that this was a very different sort of Kawasaki motocrosser. In 1989, the KXs had been some of the most conservatively styled machines in the sport. The bodywork, graphics, and color scheme were more IBM than MTV, and most people found them inoffensive and rather boring. For 1990, that conservative demeanor was completely shelved in favor of a new aesthetic that made the KX250 look like a transplant from the future. Its Buck Rogers bodywork and bold graphics screamed to anyone looking that this was a machine made for the dawn of a new decade.

|

| Plug and play: The usage of Kawasaki’s road race-inspired perimeter frame allowed items like the gas tank to sit lower and more centered in the chassis between the frame spars. The downside of this arrangement was difficulty in adding additional fuel capacity when needed. Photo Credit: Kawasaki |

On the suspension front, the all-new KX250 featured a move that most people had expected the year before. In 1989, Kawasaki had originally intended the full-size KXs to come with Kayaba’s all-new 41mm inverted forks. Inverted forks were the rage in ’89, with Honda, Yamaha, and Suzuki all making the jump to the new more rigid design. At the last minute, however, Kawasaki USA decided the forks were not quite ready for prime time and pulled them from production. While the rest of the world got inverted forks on their ’89 KXs, machines bound for the US received a version of the 46mm conventional cartridge forks used by Jeff Ward and Ron Lechien in 1988. In the end, this gamble paid off as these conventional units ended up outperforming all of the sexier, but less refined forks found on the competition.

Jeff Matiasevich had an excellent rookie year on the new KX250 leading the championship late into the season. Photo Credit: Cycle News

For 1990, Kawasaki was finally ready to take the plunge by moving to inverted forks on all of the full-size motocross machines. At the time, this move was done to improve steering precision, fork action, and chassis feel by reducing flex and thus eliminating any potential binding of the fork under heavy loads. By moving the larger and stronger portion of the forks to the clamp area, they could be made both stiffer and less prone to being caught in deep ruts. While this change did reduce some of the natural compliance of the front end, it was deemed an acceptable tradeoff for top-level motocross and Supercross use.

| Floorboards: In 1990, Kawasaki introduced the motocross world to the Supercross inspired platform peg. These massive pegs were double the size of anything offered before and an instant hit. Of all the innovations found on the ’90 KX, this has proven the most enduring. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

In order to mitigate some of this inherent stiffness, the KX’s new inverted Kayaba forks were significantly smaller in diameter than both the 46mm conventional units employed in 1989 and the 45mm inverted Showa forks found on the CR250R. For the KX, Kawasaki chose a 41mm as the ideal size to provide improved strength without compromising ride comfort. In addition to being less susceptible to flex, the new fork was also lighter than the old conventional design. Overall travel was set at 12.2-inches with 16 adjustments available for compression and rebound damping.

|

| The ‘90 KX250 introduced the motocross world to the steel perimeter frame. Employed for several years on high-performance street machines, this chassis design offered improved rigidity over the conventional designs of the time. Although sturdy, the increased width and large overall size of the new chassis made the KX bigger and less nimble than the competition. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

In the rear, the 1990 KX employed an updated version of Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak single-shock suspension system. Because of the new frame, a redesigned set of linkages was required but the new system maintained the same leverage ratio as 1989. Connecting the linkage to the alloy top shock mounts was an all-new KYB damper, which featured 16-way adjustable compression and rebound damping. The swingarm was all-new as well and featured an additional cross member for 1990 to further improve the rigidity of the KX’s chassis.

|

| Grip it and rip it: In 1990, the KX250 had the power to conquer nearly any motocross obstacle. Ryan Hughes demonstrates. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider |

On the motor front, the 1990 KX250 was new but not as radically different as the rest of the machine. In 1989, the KX had provided a strong and long powerband that was hooked up well but was a bit too mellow for some. After the powerhouse Kawasaki had provided in 1988, this shift to a smoother nature for ’89 left many riders wondering where the horsepower had gone. Slower riders enjoyed the 1989’s less-abrupt hit, but throttle jockeys lamented the loss of the old machine’s burly blast.

|

| The other big news for 1990, was Kawasaki’s switch from conventional sliders to inverted forks on the new KX. The new 41mm units were well set up and nearly as plush as the excellent 46mm right-side-up units (exclusive to the American market) from the year before. In 1990, only Suzuki offered better forks. Photo Credit: Kawasaki |

For 1990, Kawasaki looked to bring back some of the ’88 model’s powerful midrange by spec’ing an all-new cylinder, head, and exhaust. Internally, the new cylinder featured a massaging of the KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System) with both exhaust and scavenging ports receiving new profiles for 1990. A new piston was also installed that featured an Alumite coating for reduced friction and increased durability. The compression ratio, bore, stroke, and overall displacement remained unchanged but a new twin-generator ignition improved the spark, and a new airbox and air boot increased airflow to the motor. On the exhaust end, Kawasaki designed a new “low-boy” expansion chamber that improved scavenging and mass centralization. This was capped off with an all-new alloy oval silencer, which was designed to improve exhaust flow while also lowering the sound output slightly for 1990.

|

| Jeff Ward was on fire in 1990 aboard the all-new KX250. In Supercross, he took home two victories. Then in the outdoors, Wardy claimed four out of six events, dominating the series. If not for a 13th at round one, Ward would have been the 1990 250 Outdoor National Champion. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

On the bottom end, the new KX featured revised cases that were slightly wider and a revised clutch cover, which was designed to improve oil flow. The increase in case size was necessitated by the revised ignition and the all-new gear sets, which were wider for improved durability. The clutch was all-new as well and adopted the “floating” design of the KX500 to improve engagement and lever feel.

|

| One of the unique features of the 1990 Kawasaki frame was its usage of a set of aluminum hangers for the upper shock mount. While certainly trick, these hangers proved fragile and prone to failures. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

On the track, all of these changes added up to a wholly different experience on the KX250. The new motor was an absolute rocket that came on softer than ‘89 out of the hole but exploded like a stick of dynamite in the middle. Past the explosive midrange hit the KX250 continued to pull into an eye-watering top-end hook. It was far faster than in 1989 but also far more difficult to control. On a well-groomed track, the motor was brutally effective with all the power even a pro rider was likely to need. It barked out of turns and launched the green machine over any obstacle the pilot was bold enough to attempt. Where things got a bit sketchy, however, was when the track started to dry out.

|

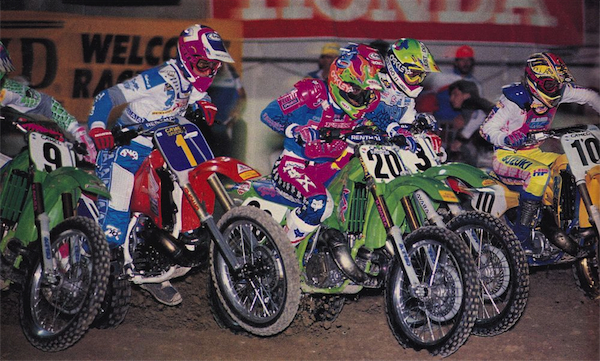

| Team Kawasaki was at the front a lot in 1990. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

On slick hardpack, the KX250 was an absolute handful. Its soft low-end and explosive midrange hit made it very hard to get hooked up and the bike liked to oversteer badly if the track conditions were less than ideal. Exasperating this handling issue was the new frame, which gave the KX a tall and top-heavy feel. The wide frame spars, tall steering head, and abrupt power made the bike feel unwieldy compared to its 250 competition. The new chassis was much stiffer than before, but the ultra-ridged frame imparted tons of vibration and made the bike feel somewhat disjointed in the turns. The super aggressive steering geometry allowed the front end to bite initially but the rest of the chassis was not always on board with this change of direction. Several riders complained that the bike felt as if the front wanted to turn and the back wanted to keep going straight. At 225-pounds, the KX was only a few pounds heavier than its competition, but it felt a good 15 pounds heavier on the track. In the air, the KX was stable, but direction changes required a great deal more body English than was required on the feathery feeling CR or RM.

After an impressive career that saw him land Factory rides at Honda and Suzuki, Johnny O’ made the switch to Kawasaki for the ’90 season. The ’83 125 National and ’84 250 Supercross champ was friends with team star Jeff Ward and was hired largely for his skills as a test rider. Although the O’Show’s best days were certainly behind him, he was still fast enough to snag a hard-earned 3rd place at the Houston Supercross. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the suspension front, the KX was far less controversial. Everyone loved the plush action of the new KYB inverted forks and some even commented that their performance eclipsed the universally praised 46mm conventional units from 1989. They were excellent at absorbing the kind of small sharp hits that pummeled the wrists of riders on Hondas in 1990. The overall action was excellent but some faster and heavier riders found the stock springs and damping a bit light. For them, an increase in oil level and maybe a step up in the spring rate was advisable.

In the shock department and the KX was also well regarded with solid and predictable performance. The shock offered a firm feel that most riders appreciated the bike could be counted on to not do anything crazy when encountering obstacles at speed. Some riders mentioned a bit of harshness in the mid-stroke and like the forks, really fast guys were likely to need a stiffer spring, but overall the KX’s suspension package was rated the second-best available in 1990.

No berm was safe from the powerful KX250 in 1990. Here Team Green’s Jeremy McGrath demonstrates. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the detailing side, the KX continued to be a bit of a mixed bag in 1990. The new bodywork was beautiful and cutting edge, but the plastic continued to be more brittle than the competition. Over tightening the gas cap was a sure recipe for a lap full of 93 octane and nearly all the bolts and nuts were easily stripped. The brakes, while powerful, were somewhat grabby and subject to the need for constant bleeding. The new massive platform pegs were innovative and super comfortable, but the springs and mountings both proved fragile and prone to failure. The super trick alloy shock hangers also liked to crack and it was imperative to keep a close eye on them if you wanted to avoid a potentially painful failure.

If looks alone won shootouts, the 1990 Kawasaki KX250 would still be undefeated. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Overall, the 1990 KX250 was an incredibly bold step for Kawasaki. Its radical and revolutionary design broke new ground in chassis construction and pushed the envelope of motocross aesthetics. It proved incredibly popular in the showrooms and on the track. It may have been big, tall and heavy, but it also looked like a million bucks and ran like a Top Fuel dragster. Its avant-garde design influenced styling for much of the decade to come and paved the way for the twin-spar alloy machines that are ubiquitous today. Wicked fast, cutting edge, dead sexy, and a bit unrefined; the 1990 Kawasaki KX250 was the perfect machine to launch team green into the new decade.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter-@TonyBlazier