For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at Suzuki’s first entry into the rough and tumble world of 450 four-strokes, the 2005 RM-Z450.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at Suzuki’s first entry into the rough and tumble world of 450 four-strokes, the 2005 RM-Z450.

|

|

Better late than never: In 2005, Suzuki finally got into the 450 four-stroke game with their RM-Z450. While far from perfect, the RM-Z was a very solid first effort and one of the best bikes of 2005. |

Today, we live in a valve and cam world. Of the big five manufacturers, only two make full size two-stroke machines and of them, only one takes the smokers seriously. In motocross today, you ride a thumper, or you’re probably not serious about winning. A mere decade ago, however, that was not the case.

|

|

The all-new power plant on the RM-Z450 cranked out a pleasant flow of ponies from its 449cc’s. Mellow down low, meaty in the middle and mediocre on top, it was competitive, but not omnipotent. |

In the early 2000’s, thumpers were still a bit of a novelty. Only one of the Big Five made a 250 four-stroke and only two had 450’s (one of them actually being a 426, the other being a slightly quirky Austrian of Swedish decent) in production. After Yamaha had caught the industry napping in 1998 with their revolutionary YZ400F, it had taken five years for Japan to debut a challenger. In 2002, Honda unveiled the first legitimate threat to the omnipotent YZF, the all-new CRF450R. The CRF450R was lighter and more user friendly than the YZF, but slightly slower and less sharp in the turns. In spit of these shortcomings, the red thumpers flew off dealer’s showrooms in droves. Within a year of the CRF’s introduction, nearly every track in America was awash in Honda thumpers. It was like the second coming of the Elsinore and Honda could not build them fast enough.

|

|

Question: What do you get when you marry a KX chassis to an RM motor? Answer: A colossal disappointment that fails to satisfy fans of either brand. The 2004 RM-Z/KX250F might have started out as a good idea, but it ended up being a black eye for both manufacturers. With the new RM-Z450, Suzuki would forgo the alliance and do all the development in house. |

With Yamaha and Honda cranking out thumpers faster than you can say “cash cow”, both Kawasaki and Suzuki were left licking their wounds in the early 2000’s. Even though two-strokes were still the majority of the machines being sold, it was pretty clear which way the market was shifting, and neither one had any skin in the game. This glaring necessity would lead the green and yellow brands to team up to form what would be known as the Kawasaki/Suzuki alliance in 2001. At the time, it was thought that both manufacturers would benefit by combining their efforts. They could pool their resources, divide the development cost and capitalize on what each one did best. The alliance would allow each to share models within their portfolio (yay, yellow KX60’s!) and fill out gaps in their product line (yay, green DRZ400’s?). Perhaps most important of all, the two would be teaming up to develop an all new racing thumper.

|

|

In 2004, Joël Smets would be hired by Suzuki to help shake down the all-new RM-Z450 in the Motocross World Championships. He would be joined by Steve Ramon and Kevin Strijbos on the works RM-Z’s. |

Not to spoil the story, but to say this marriage did not go well would be a massive understatement. The RMZ/KXF 250 that resulted from this experiment was a mish-mashed mess, which played on the strengths of neither and satisfied no one. It was slow, mediocre handling and worst of all, terribly unreliable. After a few years of this wedded bliss, it was decided that it might be best for both parties to go their separate ways. Suzuki and Kawasaki realized that for their bikes to be successful in the market, they needed to be true to what made their customers happy. In the cut-throat world of four-stroke motocross, no halfhearted effort was going to do.

|

|

When designing a frame for the new thumper, Suzuki decided to go with a twin-spar aluminum chassis similar in design to the ones Honda had been using since 1997. The new alloy frame would use a combination of forging, stamping and casting technology to give the new Zook a solid feel and razor sharp manners. |

While Suzuki had been developing their 250F program in conjunction with Kawasaki, the 450 program had remained strictly in house. Part of the issue many people had with the 1st gen RM-Z250, was that it did not feel like a Suzuki. In truth, the chassis on the RM-Z was 100% Kawasaki and the bike had none of the handling flair the yellow bikes had become famous for. This meant riders who bought the new RM-Z250 expecting a better handling YZ250F, were in for a bitter disappointment.

|

|

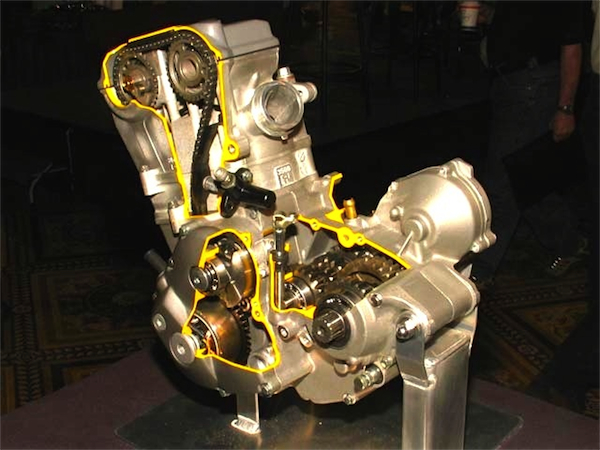

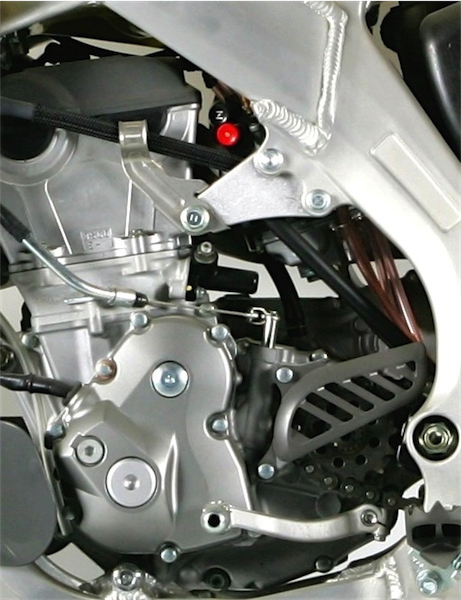

When designing the new RM-Z mill, Suzuki went with a fairly conventional design pilfered from their GSX-R sport bikes. The top end featured a dual over-head cam, four-valve layout that was adjusted via shim and bucket. The piston was a short skirt, slipper style and the oiling system was an innovative semi-wet sump design. Suzuki innovations included the Suzuki Advanced Sump System (SASS), which positioned the crankshaft lower in the crankcase to reduce the center of gravity, and the Suzuki Active Vent System (SAVS), which reduced crankcase pressure. |

With the all-new 2005 RM-Z450, Suzuki was determined not to make that mistake again. Even though the 450 RM-Z was going to use an all-new four-stroke motor, it was critical that the bike retain its “Suzukiness”. This meant unparalleled steering precision, mated to a light and airy feel. The new bike had to feel like a Suzuki and play on the strengths the brand had developed. To accomplish this, Hamamatsu ditched the steel perimeter frame of the RM-Z250 and set about developing an all-new chassis for the 450.

|

|

In June of 2004, Team Suzuki Rider Steve Ramon would score the first ever moto win for the new RM-Z450 at the St Jean d’Angely track in France. |

Today, the twin-spar alloy frame is all but ubiquitous on Japanese motocross machines, but in 2004, the jury was still out on the best chassis design. Honda had been the first manufacturer to jump on the twin-spar alloy bandwagon in 1997, and was still the only manufacturer using it in 2004. Yamaha had stuck with steel for their YZF and many people were still questioning the merits of the aluminum design. The alloy chassis’ looked cool, was super strong and could be made lighter in theory, but the rigidity and feel of the aluminum was tricky to get right.

|

|

By going with a four-speed transmission on the RM-Z, Suzuki limited the appeal of the new machine to motocross enthusiasts only. While this was common on 450’s of the time, popular demand would necessitate a move to more versatile five-speeds by the latter part of the decade. |

For the RM-Z450, Suzuki decided to go with a twin-spar alloy design similar to the one employed by Honda. Although Suzuki had never used this design for motocross, it did have extensive experience with it on their GSX-R street machines. While the new chassis looked superficially like the one found on the CRF (rumors at the time had Honda suing for patent infringement), the two actually had nothing in common. The RM-Z’s frame was larger overall and of a slightly different design from the CRF. The new Suzuki frame used a combination of forging, stamping and casting technology to produce a unique Suzuki spin on a proven design.

|

|

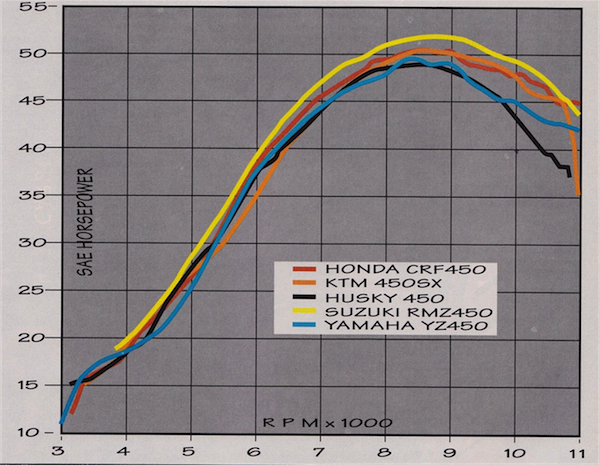

Numbers can be deceiving: On paper, the Suzuki looked to be the star of the 450 class. With a broad curve that maxed out at 51 horsepower, it topped all comers on the dyno. In the real world of loam, jumps and berms, however, the 2005 CRF450R was faster, torquier, and unassailable as the top motor of 2005. |

For the motor, Suzuki went their own way with an all-new design for the 450. The new mill featured a 95.5mm bore by 62.8mm stroke and displaced 449cc’s. The head was a rather conventional dual over-head cam layout and featured twin forged, hollow-ground, camshafts activating four titanium valves (this was in contrast to the unique “Uni-cam” of the Honda and five-valve “Genesis” arrangement of the Yamaha). For the piston, Suzuki went with the short-skirt, “slipper-style” design like the one pioneered on the original YZ400F. This design offered the low friction and light weight necessary to attain the high rpm’s needed in a racing four-stroke.

|

|

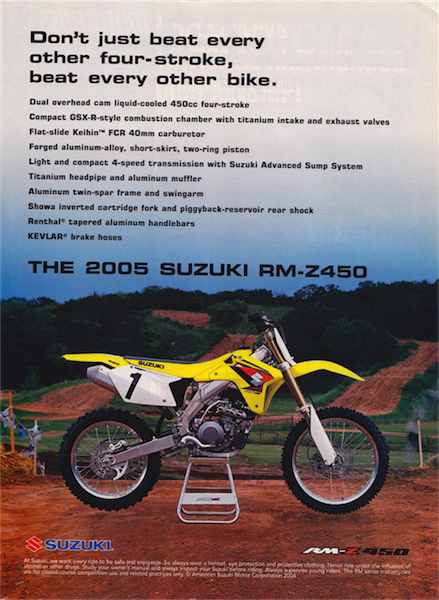

Fashionably late: Originally scheduled for release in the fall of 2004, production delays, rumored litigation (Honda reportedly sued over some aspects of the RM-Z’s frame design) and unforeseen problems would hold up the arrival of the RM-Z until early 2005. |

|

|

The American debut of the RM-Z450 would come in the 2005 Supercross series at the hands of two-time World Motocross champ Sébastien Tortelli. Tortelli’s best finishes on the yellow thumper would be trio of fourths at Anaheim, Atlanta and Dallas. |

One unique feature of the RM-Z450 motor was its lubrication system, which was originally pioneered on the RM-Z250. The new mill used a semi-dry sump design that tried to use the best of both the Honda and Yamaha’s strategies. With the Honda, the transmission and motor oil were separated to prevent contamination from the clutch and trans from reaching the delicate crank and top end. The advantage of this was low weight (due to no external oil reservoir) and hopefully, greater reliability. The downside of this was the potential for oil starvation due to the systems limited capacity.

|

|

And then there were three: With the addition of the RM-Z450, only Kawasaki was left out of the 450 motocross game in 2005. Kermit-crosser fans would have to wait one more year for Kawasaki to unveil their version of a 450 racing thumper. MotorcycleUSA.com photo |

|

|

The 47mm “Twin-Chamber” (so named for its sealed internal oil cartridge which prevented air contamination in the damping fluid) Showa forks on the RM did a masterful job of taming the track in ‘05. They were stiff enough for anything short of Supercross, while plush enough to take the bite out of choppy outdoor style hits. These were excellent forks. |

With the Yamaha’s dry sump design, the oil was shared throughout the motor, but pumped into an external tank that added capacity and aided in cooling. The addition of several filters helped cut down on particulate contamination and there was less oil anxiety with the YZF’s additional oil reserve. The downside of the Yamaha’s system was weight (most race teams of the time ditched the oil tank and converted the YZF over to a wet-sump system), as it carried both the tonnage of the additional oil and its reservoir.

|

|

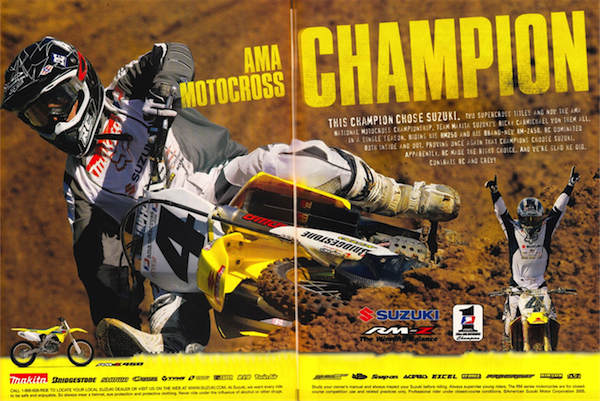

Even though Suzuki already had a production bike in dealer’s showrooms, they elected to use their one year works bike exemption for RC’s Factory RM-Z450 in 2005. One interesting difference between Tortelli’s and Carmichael’s RM-Z’s, was the champ’s decision to run a Pro Circuit exhaust instead of Sébastien’s Yoshimura pipe. |

With RM-Z’s design, Suzuki tried to enjoy the benefits of both systems, while mitigating their downfalls of either. The RM-Z450’s semi-dry sump system comingled the transmission and crankshaft oil like the Yamaha, but separated the two by a shelf that helped lessen cross contamination. It carried more oil than both the Yamaha and Honda (1.5 quarts), but did away with the heavy tank and lines of the YZF. Internally, the piston and crank were lubricated by misters and excess oil was siphoned off to the oil pump to prevent the crank from having to travel through pooled oil.

|

|

When designing the RM-Z power plant, Suzuki looked at what the competition was doing and tried to come up with a better mousetrap. The semi-dry sump design Hamamatsu employed tried to combine the additional oil capacity of Yamaha’s dry sum system (1.5 liters), with the weight savings and lack of cross contamination offered by Honda’s sealed wet-sump design. |

Perhaps the most controversial facet of the RM-Z’s motor was its transmission. In 2004, only the Honda CRF450R came from the factory with a five-speed transmission. Both the YZ450F and KTM 450SX came with four-speeds that limited their usefulness for anything but pure motocross. At the time, many factory bikes were funning three-speeds, so it is not hard to imagine the reasoning behind this. By dropping fifth gear, precious ounces could be saved on an already porky class of machines. While this seemed to be a reasonable decision, this was a move not appreciated by many consumers who preferred the versatility of a five-speed trans. In the case of the Suzuki, this problem was exacerbated by two factors that would conspire to limit its effectiveness in stock form – power spread and stock gearing.

|

|

With its tall stock gearing, four-speed trans and soft bottom-end, the RM-Z could be tough to keep on the pipe at times. Most riders benefited from lowering the gearing and adding a pipe to punch up the ponies. |

On the track, the 2005 RM-Z450 pumped out a pleasant and mellow (for an Open bike) spread of ponies. It was smooth off idle, muscular in the middle and mediocre on top. Power was electric and less abrupt than the hard-hitting Honda. While it was not as fast as the CRF, it was on par with the YZF and KTM. On the dyno, it pumped out a very impressive 51 horsepower, the most of any 450 in 2005. On the track, however, it was more pleasant than awe-inspiring, and a tick behind the Honda.

|

|

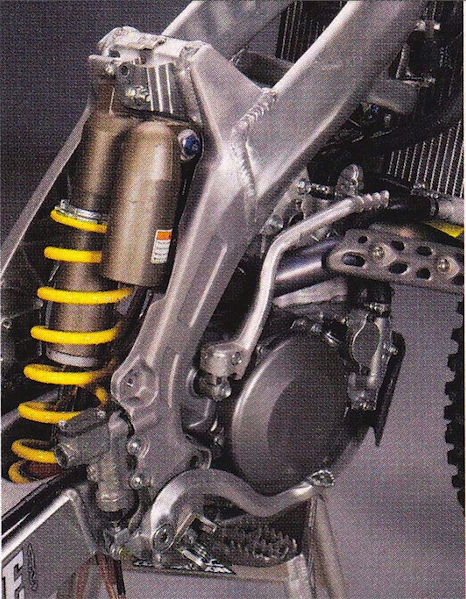

The rear Showa shock on the RM-Z450 was one of the best rear ends of 2005. |

With its somewhat lackluster low-end, the four-speed was more of a handicap than it had been on the burly Yamaha and KTM. Where the Y-Zed and Katoom had had the torque to pull the gaps easily, the electric RM-Z tended to lie down between shifts. Making matters worse, was the stock gearing, which was very tall (probably to give the bike some semblance of a top speed) and gave the bike a sluggish feeling. With the stock gearing in place, first and second were very tall and the bike could be easily stalled in tight turns. Flame outs were a big problem on these pre-fuel-injection thumpers and the RM-Z was often a victim of the cough and die syndrome.

|

|

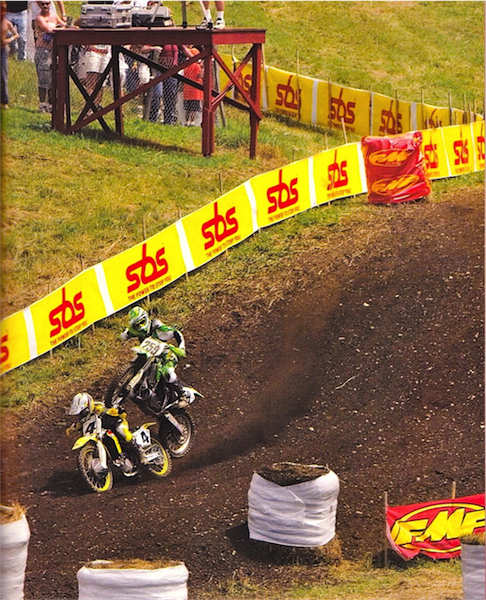

You brought a knife to a gun fight: The 2005 season was supposed to bring moto fans the long anticipated Bubba vs. RC showdown, but JS259 was badly outgunned once they took the fight outdoors. Without a 450 in his arsenal, Stewart gave up 200cc’s and literally had to ride the wheels off his KX250 to try and keep the thundering RM-Z in sight. |

While motor performance is always important, when it comes to Open bikes, it is had to get too picky. Pretty much any 450 can scare the crap out of you and jerk your arms from their sockets. With big powerful and heavy bikes like these, the hard part is making them rideable. That is where Suzuki hit the sweet spot with the 2005 RM-Z. It was fast, without being scary, and easy-to-ride, without being slow. When you added in its very good transmission (smooth shifting, as long as the bike was not over revved) and nearly flawless clutch, it was a very solid motor package. It was by no means the fastest bike in the class, but with a gearing swap and a pipe to open up the top end, it could run with the class leaders.

|

|

Fat Bro: The addition of a Renthat Fatbar as stock equipment on the RM-Z450 was big news in 2005. The rest of the Suzuki lineup got generic alloy bars that lacked the cachet of the UK brand. |

While the motor package may have had some caveats in 2005, the new chassis made apologies to no one. The new twin-spar frame was a bit larger than the Honda, and gave the bike a rather tall and big feel, but oh could she dance. With the introduction of the 2005 RM-Z450, it could finally be said that there was a big bore thumper that could handle on par with a 250 two-stroke machine. Up to this point, all big-bore four-strokes felt pretty much like exactly what they were, big heavy Open bikes. They may have been easier to manhandle that a CR500R, but they were never going to be confused with a RM250. With the new RM-Z, Suzuki finally found a way to translate that light feel and precise handling people loved about their two stroke machines and translate it to the world of shims and buckets. Compared to the RM-Z, every other 450 was a locomotive. It craved the inside and could be flicked around like a bike that weighted immensely less than its 233 pounds. Yes, it was a little busy at speed (like every other Suzuki since 1989, save the RM-Z250), but it made up for that wiggle with the ability to turn under any other machine in the class.

|

|

Brakes on the RM-Z were considered very good for the time. They were on par with the Honda, but less powerful than the excellent Brembo’s on the KTM. |

In 2005, the other half of Suzuki’s award winning handling story was its excellent suspension package. Up front, the RM-Z used a set of 47mm Showa Twin-Chamber forks to handle taking on the bumps. These magnificent forks were set up extremely well and did a great job of pleasing both novices and pros. They were plush, without being soft and stiff, without being harsh. In 2005, these 47mm Showa’s were the best forks in motocross.

|

|

During the summer of 2005, Carmichael and Stewart enjoyed several spirited battles, with more than a few ending with the #259 on the ground. This run-in between the two at Unadilla would end with both down in a heap and Stewart KO’d for the day. |

Out back, the RM-Z used a Showa shock to punch out 12.2 inches of plush travel. Featuring a 50mm aluminum body and 18mm shaft, the Showa piggyback unit offered selectable hi and low speed compression settings as well as rebound adjustability. As delivered, the RM-Z offered an excellent ride that gobbled up bumps big and small. The bike tracked straight and true in the whoops and never kicked or hopped unexpectedly. On a big and powerful bike, suspension is often more critical than power, and the RM-Z450 pilot could come in hot and slam through the bumps without fear in 2005.

|

|

Calling Doctor D.: Perhaps the most annoying detail on the new RM-Z was its old school positioning of the hot-start lever on the carburetor. This made getting to it in the heat-of-the-moment a major pain. |

In addition to its excellent handling and suspension, the RM-Z had a lot of nice features going for it in 2005. The stock headpipe and footpegs were both made of titanium for light weight. Bodywork was clean and the bike looked good (except for a slightly odd rear fender). Although the bike was pretty large overall, ergonomics were excellent and the bike had a comfortable feel. One major win for the RM-Z was the addition of a Renthal Fatbar as standard equipment. This was a major win in an era where most Japanese bike came with junk bars as standard equipment.

|

|

Wining machine: RC took a major gamble in 2005 signing with Suzuki to ride a bike that was completely unproven. Fortunately, the gamble would pay off for both, with Suzuki’s first 250/450 title since Greg Albertyn did the deed in 1999. |

In the not awesome category, were the bike’s airbox (so impossible to use that it was actually easier to remover the filter from behind the left sidepanel), hot start (mounted to the carb like the original YZ400F and nearly impossible to find in the heat of the moment) and propensity to flame out unexpectedly (exacerbating the hot start problem).

|

|

In September, RC would cap off a brilliant year on the new RM-Z450 with a dominant victory at the Motocross of Nations in Ernee, France. |

|

|

A full eight years after the introduction of the revolutionary YZ400F, Suzuki would finally get into the thumper game with a big-bore four-stroke of their own. The 2005 RM-Z450 was far from perfect, with its slightly big feel and gappy trans, but it was fun to ride and competitive. In 2005, nothing could outclass the omnipotent CRF450R, but the RM-Z came the closest to unseating the champ. |

Overall, the 2005 RM-Z450 was a very good first effort. It was leaps and bounds better than the disappointing RM-Z250 and more than competitive with the bikes in its class. While it was not quite up to beating the incredible 2005 CRF450R (a bike many people still consider one of the best motocross bikes ever built), it could stand its ground against any other comer. It had excellent suspension, razor sharp handling and a solid motor package. With one more gear and a bit more grunt, it could have been the champ.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter-@TonyBlazier