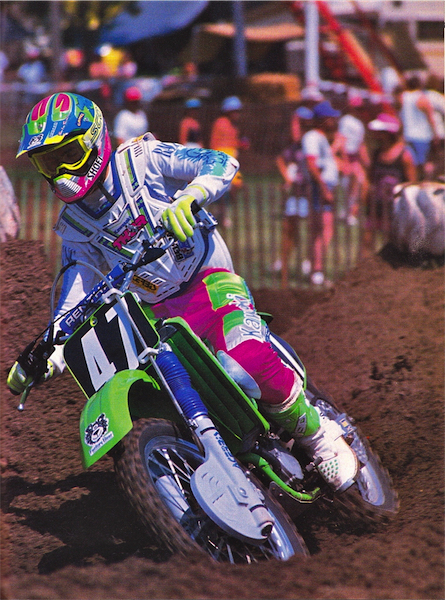

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look at the bike that took Jeff Matiasevich to the 1989 West Coast Supercross crown, the 1989 Kawasaki KX125.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look at the bike that took Jeff Matiasevich to the 1989 West Coast Supercross crown, the 1989 Kawasaki KX125.

|

|

In 1989, Kawasaki brought a knife to a gun fight in the 125 class. After taking the MXA shootout victory in ’88, the new KX lacked the ponies to run with the true thoroughbreds of ’89. |

In the early days of American motocross, Kawasaki was little more than a bit player. While they enjoyed some success at the professional level with riders like Jimmy Weinert at the controls, their production bikes were largely uncompetitive and outclassed by the competition. In the seventies, very few dealers even bothered to stock the green machines and finding one was usually the hardest part about riding a KX.

|

|

In the seventies, Kawasaki’s little KX125 was largely the forgotten member of the Big Four. Slow, under suspended and nearly impossible to find, the KX125 was more of a curiosity than a contender. |

As the decade of the seventies drew to a close, Team Green finally started to make some headway in the motocross market. In 1978, Kawasaki would release an all-new machine that would signal their rededication to the 125 class, the KX125-A4. The A4 was fast, light and as up-to-date as anything in the class. Then in 1980, they would beat the competition to the punch with their all-new “Uni-Trak” KX125. The new KX would be the first machine to feature a rising rate, monoshock rear suspension, beating Suzuki and Honda by a full season. Then in 1982, they would lead innovation by being the first manufacturer to offer a front disc on their motocross machines.

|

|

In ‘88, Kawasaki spec’d an all-new 56mm x 50.6mm 124cc case-reed mill for their eighth-liter racer. The new motor featured the most advanced power-valve system in the class and delivered a wide powerband and punchy delivery. For ’89, Kawasaki went searching for more top-end power, and found it, but unfortunately killed all the fun in the process. |

While no one could accuse them of being too conservative, this innovation did not translate into shootout victories. The KX125 was certainly no longer the class whipping boy, but neither was it up to unseating the omnipotent RM125. Then in 1984, the power structure of the 125 class finally took a turn to the green side of the spectrum. In the 125 class, power is everything, and in 1984 no other machine could run with the KX125. The KX tiddler still handled a little funny and lacked the RM’s suspension finesse, but oh was she fast. It dominated the competition and took Jeff Ward to the 1984 125 National Motocross Championship.

|

|

Murder’s row: In ’88, Kawasaki won MXA’s shootout (Dirt Rider and Dirt Bike picked the CR as best in ’88) based more on the shortcomings of its competition than any great virtue of its own. For ’89, that task was going to be a lot harder with the KX facing much steeper competition from three greatly improved entries. |

After this breakthrough year of ’84, what would follow would be a rather uneven run of good and not-so-good KX125’s. In 1985, Kawasaki would once again dominate the motor category with their rocket-fast KX, but be held back by poor suspension and cantankerous handling. The next year, the KX would lose the power sweepstakes to the awesome Honda CR125R and its broad torquey delivery. For ’86, Kawasaki went for maximum top-end power on their “Works Replica” KX125, and the result was a hard-to-ride mess. The next year in ’87, Kawasaki would bring back the mid-range and a more user-friendly powerband, but bolt it to terrible TCV forks that were light years behind Honda and Suzuki’s offerings. For ’88, Kawasaki would finally break through with an all-new and much improved KX125. The new ’88 KX offered a solid power spread, very good suspension and none of the odd handling quirks that had typically plagued the brand. It was no rocket and certainly no beauty, but it was a solid overall package that was good enough to be crowned MXA’s top 125 of ’88. With ’88 in the rearview mirror and an all-new batch of contenders on the way, the question would be, would the “good enough” be up to taking the crown again in 1989?

|

|

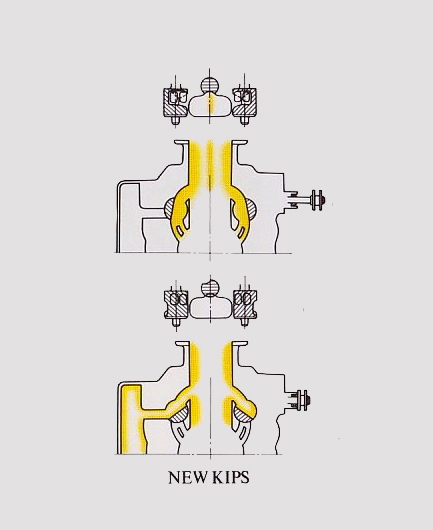

Cutting edge: In 1985, Kawasaki introduced their unique version of the two-stroke “power- valve” on their KX125. Dubbed KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System), the Kawasaki system combined the exhaust resonance chamber of the Honda ATAC and the variable exhaust port design of the Yamaha YPVS into one system. By the mid-nineties, nearly all the manufacturers would be using a system similar to the KIPS on their race machines. |

With the 1988 KX125 being all-new, Kawasaki looked more toward refinement, than redesign for 1989. A new larger fork graced the front end and a steering angle change pulled things in a half a degree from 27 to 26.5 degrees. In the motor, the engineers modified the KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System), enlarged the ports and lowered the compression in an attempt to extract more ponies. While the ‘88’s bulky and unattractive plastic remained, a new seat improved comfort and a switch to dual pistons for the front brake promised improved pucker power.

|

|

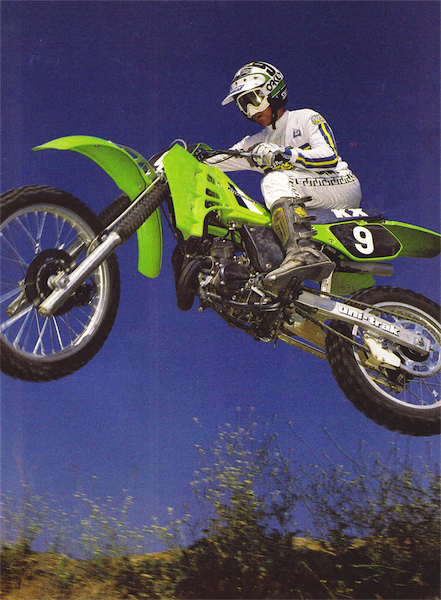

The Kermit Komet: In 1984, Kawasaki’s run of 125 futility would finally end with the introduction of their rocket-fast ’84 KX125. The green meanie ripped through the powerband like it was a 175 and left the other 125’s in its wake. Nineteen eighty-four 125 National Champ Jeff Ward demonstrates. |

In 1988, the KX125 had provided the a wide spread of power that was punchy and competitive. It was not necessarily the most powerful, but what power it had was properly placed and easy to use. For ’89, Kawasaki tried to pump up the top-end, without neutering their excellent mid-range power. On the dyno they succeeded, with the ’89 KX mill punching out a full two horsepower more than the potent ’88 had. On the track, however, things did not look as rosy.

|

|

Originally, all full-sized ’89 KX’s were supposed to come equipped with Kayaba’s spiffy new 41mm inverted cartridge forks. At the last minute, however, Kawasaki USA pulled the plug on that idea and switched to 46mm conventional KYB’s for the US market. This was done in part due to the input of US test riders, who preferred the old-school design and in part to undercut the price of the new Hondas, which had received a major price bump for ’89. |

Ironically, it was exactly the same mistake Honda had made their year before with their omnipotent CR125R. In ’86 and ’87, the CR had belted out a hard-hitting rocket of a powerband that threw sand in the face of its 125 competitors. For ’88, however, Honda tried to smooth out their powerhouse and lengthen its top-end pull. The result was a listless “lap-time” motor that was fast on paper, but boring to ride. For ’89, Kawasaki fell on this same sword with a smooth and uninspired KX125 powerband.

|

|

Slow burn: In ’89, Kawasaki turned their punchy and fun ’88 mill into a dull “lap-time” motor. The new mill pulled over a broader range, but lacked any kind of hit or burst. While it was certainly easy-to-ride, it was boring to race and not popular with most riders. Novices preferred the punchy “right now” power of the RM and YZ and fast guys gravitated to the endless pull of the CR. It was competitive, but not fun. |

For ’89, the previously punchy 124cc mill lost all of its hit and traded it in for a long and languid flow of power. On a burly 500, this would have been awesome, but on a rev-happy 125, this meant slow. The power was long and drawn out, with absolutely no hit or burst. This made it easier to ride than the mid-range only Yamaha and pro-focused Honda, but slower on any track where traction was prevalent. If there was deep loam or sand, the problem got even worse, as the KX’s lack of torque made it prone to bogging between shifts. While it technically offered the widest actual powerband in the class, it was by far the least fun to ride. It was less quick than the punchy RM and YZ and far less fast than the rocket-ship Honda. In the end, it was the Honda on top for the fast guys and the Suzuki on top for the novices, with the punchy but narrowly focused YZ and snooze inducing KX somewhere in between.

|

|

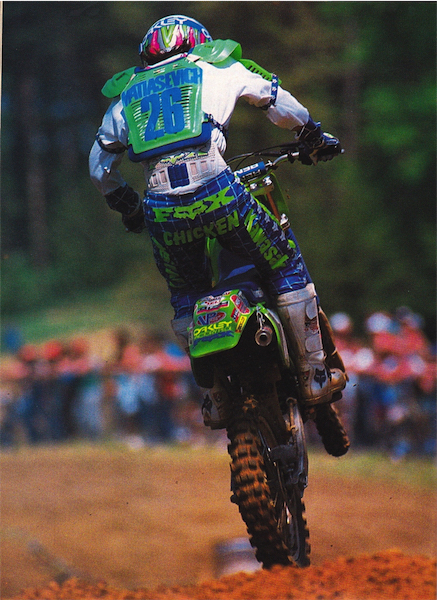

Peat and repeat: While the stock KX125 was no great Supercross machine, that fact did not stop Jeff Matiasevich from dominating his way to a second straight 125 West Coast Supercross title in ’89. |

On the suspension front, things were pretty interesting in 1989. By 1988, all the manufacturers had finally adopted the cartridge damping systems for their forks and the quality of fork action was getting better by leaps and bounds. After the cartridge damper, the next big evolution on the horizon was the inverted or “upside-down” fork. This design had first been seen on the GP circuit in the early eighties and offered several advantages over their more conventional cousins. The first advantage was the lack of overhang below the front axle that made navigating ruts easier. The second major benefit was the added rigidity offered by placing the large end of the forks at the top where, it interfaced with the clamps. This made a major difference to riders like Rick Johnson who liked to attack the whoops and charge into obstacles.

|

|

While the last minute switch back to conventional may have not been popular with the marketing department, it was certainly a win for consumers. The beefy 46mm KYB’s were very similar to the works forks run by Ward and Lechien in ’88 and head and shoulders better than anything else in the class. |

The downside of the inverted design was that very same rigidity, which made the new USD’s far harsher than their right-side-up counterparts. While pro’s like Johnson and Ward could make the most of this new found strength, mere mortals found most of these early USD’s less pleasant than the old design. Interestingly, even though these early USD’s actually performed worse than the old configuration in many ways, there was a great deal of market pressure put on the manufacturers to switch to the new hardware. Ready or not, the inverted fork was perceived as the future and in motocross; the future is always now.

|

|

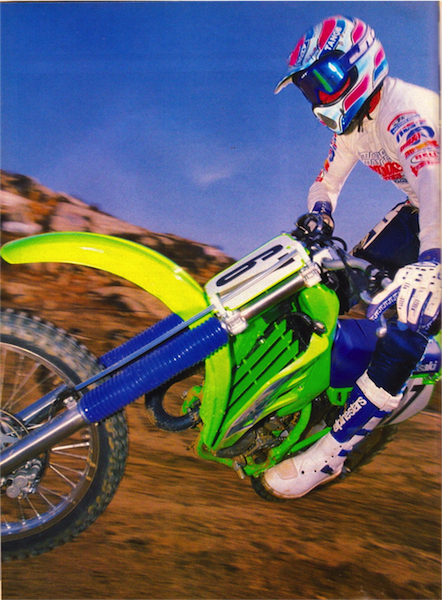

While the ’89 Kawasaki was no fire-breather, it was still a very fine racing machine. Excellent suspension, crisp handling and an easy-to-ride powerband made it a great entry level mount. For fast intermediates and pros, however, some serious motor work was going to be needed to keep the red rocket in your sights. |

For Kawasaki, this fork dilemma had them at a bit of a quandary going into the 1989 season. Originally, the entire KX lineup had been set to receive Kayaba’s all-new 41mm upside-down forks, but at the last minute, Kawasaki USA got cold feet. Test riders still preferred the feel of Kayaba’s excellent 46mm right-side-up cartridge sliders and persuaded the manufacturer to buck the trend and eschew the new hardware. While Kawasaki worldwide went forward with the inverted forks, Kawasaki USA kept the old school design for ’89.

|

|

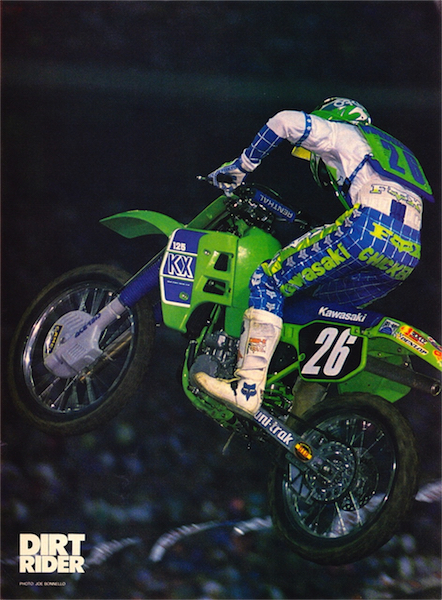

Frodaddy: In 1989. Jeff Emig was one of Kawasaki’s up-and-coming stars on the KX125. After a somewhat lackluster two seasons on the brand, he would switch to Yamaha for the ’91 season. In 1996, Emig would return to Team Green and deliver the brand a Supercross and two 250 National Motocross Championships. |

While this may have been a marketing gamble, on the track, this move turned out to be the right call. In 1989, the 46mm KYB’s were by far the best forks on the track. They were more rigid than the old 43mm conventionals found on the Honda, but less harsh than the Inverted sliders found on the Yamaha. In the bumps, they were exceedingly plush and gobbled up hits big and small with nary a whimper. Spring rates were spot on for anyone less than 180 pounds and worked well for riders of all skill levels. Behind the KX, were the not-quite-as-smooth RM, slightly harsh Honda and undersprung and bottoming prone YZ.

|

|

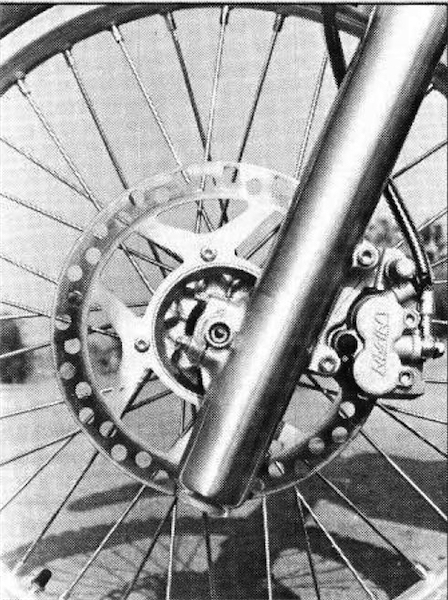

For 1989, Kawasaki upgraded the KX’s front brake from a single, to a dual-piston binder. Even though all four Japanese manufactures used Nissin as the supplier of their brakes, each brand offered unique performance. Even with the switch to the dual piston caliper, the KX could not match Honda’s combination of outright power and braking feel. |

Out back, the Uni-Trak rear was just as well sorted as the forks and offered the best ride of ’89. The geometry, linkage, spring and KYB shock all combined to afford a smooth ride that tracked straight in the rough and never surprised its pilot. Smooth was the name of the game, with a plush feel and no sudden spikes or jolts. In the suspension wars, only the Suzuki was close, with a similarly plush feel, but less bottoming resistance on hard hits. In third and fourth we had the Honda and Yamaha, which suffered from a slightly busy feel (CR) and harsh damping (YZ).

|

|

In 1989, this was the best rear suspension in the 125 class. Punching out a full 13 inches of travel, the KYB shock on the KX gobbled up hits big and small with nary a whimper. |

While Kawasaki had enjoyed decent success in the motor department throughout the decade, the handling side of the equation had eluded them. The early Uni-Trak bikes were high-tech, but burdened with a tall and top-heavy feel than made them unwieldy handlers. While later variations improved, none of the pre-’88 KX125’s could be considered anything more than a mediocre handler. In 1988, the new frame brought with it a more stable and planted feel and slightly better cornering performance. It was certainly no scalpel in the twisties, but it got the job done and was rock solid at speed.

|

|

Smoked: While the KX’s lack of horsepower was not a major handicap indoors, the outdoors were another matter. In the 1989 Motocross Nationals, the underpowered KX’s and RM’s struggled mightily to keep the powerhouse Hondas in sight. Even privateer Hondas like the Pro Circuit CR125R of Donny Schmit were clearly faster than the factory green and yellow machines. |

For ’89, Kawasaki pulled the head angle back half a degree, switched to beefier forks and tucked axle alignment in, stiffened the frame, mounted a 19” wheel and lowered the overall weight of the chassis. The result was a whole new kind of KX. For the first time in the history of ever, the KX125 actually handled. Gone was the front end push and pedestrian turn in, to be replaced with a planted feel and razor sharp manners. This new breed of KX could actually turn with anything on the track. It was not quite as sharp as the Honda, and not quite as feathery feeling as the RM, but it retained its stability from the year before and could be dive-bombed through high-speed sections that would terrify a Honda or Suzuki pilot. Overall, the ’89 KX125 offered the best handling package of the 125 class.

|

|

In 1986, Kawasaki had been the first manufacturer to put a rear disc on their 125 machine. While more powerful than a drum, these early disc were often very grabby and hard to modulate. The ’89 KX was no exception, offering very little adjustment at the pedal (savvy riders ground down the clevis bolt to allow more play) and a light-switch like engagement. |

In the details department, the KX was still a few ticks behind the best in the class in 1989. The new dual- piston caliper Nissin front binder was squeaky and less powerful than the similar units found on the Honda and Suzuki. Out back the rear disc was powerful, but grabby and difficult to modulate. While the new seat foam was an improvement, overall ergonomics remained bulky and less refined than the other 125’s. Plastic quality was poor, with gas caps and fenders a particular point of concern. Footpeg life was likewise very suspect, with drooping mounts and broken springs the order of the day. Care needed to be taken when tightening things like the seat bolts, silencer and sidepanels on the KX as well, because the riv-nuts inserted into the rear subframe were of the pot metal variety and easily stripped. Frame breakages were common and it was important to always keep an eye out for telltale cracks than could lead to a very painful catastrophe. Lastly, Kawasaki’s choice of a very old-school single radiator not only made the bike look ancient, it also meant that your stock decals had to contend with the gas fumes making their way through the plastic tank. Predictably, stock decal life was grim.

|

|

Here’s Matthes on his ’89, balls on fire and on the gas. |

Before we wrap this week’s walk down moto history lane up, I thought it would be enlightening to get the input of a true champion who actually put in a grueling season on the KX125. I give you the four-time champion of Manitoba Province and tuner to the stars – Steve Matthes.

Blaze does a great job with these articles and when he told me he was doing one on the 1989 KX 125, I felt like I had to chime in. I had this bike and lived with it for a year; and I couldn’t wait to get rid of it. I rode Kawasaki’s in the 80 class and they were great bikes. Since I was getting some small help from Kawasaki Canada, we stuck with them in ’89 and picked up a KX125.

The first time I rode it in the spring in deep sand, I thought it was broken. Seriously, that’s how slow it was. Upon further inspection, it wasn’t broken. It was just that slow. To make matters worse, I jumped on a buddy’s ’89 CR125 and that destroyed my confidence in my ability to capture yet another prestigious Manitoba motocross title.

That was it for Tom (my dad). He shipped the cylinder and head off to Pro Circuit to get the complete works port job along with a pipe, silencer, jersey and a seat cover. It was some sort of package deal by Mitch (years later I would find out that my boss at Yamaha, Jimmy Perry, was basically responsible for all the customer stuff around that time and probably ported my cylinder himself – weird right?) and his crew. We got it back for the price of a small car (the Canadian dollar was worth about 60 cents US back then), bolted it on and waited for the shit to happen.

But nothing really happened. It was still very slow, almost electric feeling (DAMN YOU PERRY!!!). PC had helped it, but not very much. On the bright side, I did have a sweet seat cover. Again, my buddy’s Honda was stock and WAY better than this thing.

I wish that were my only problem with the bike. I came up short on a double and cracked the gas cap threads off with my nuts. That actually didn’t hurt nearly as bad as the gas on the balls did. I finished the race and then had to soak my nuts in water for thirty minutes to stop the burning. I stripped out bolts on the sub-frame, the frame itself cracked, the pegs rattled badly and again, it was SO SLOW.

In fact while waiting for a new gas tank to come in, my dad had his ’87 CR125R laying around and somehow bolted on the KX’s complete front end. I raced it and despite being two years old, it was way better than the green machine. My results turned out to be better on it as well. I rode the Millville national amateur day and won my class which got us into a halftime race at the next day’s national with the top two in every class or something like that. Up against 250’s, 500’s and all that, I almost pulled the holeshot on that bike. Yeah my chain broke two laps later coming out of the sand, but still…

Anyways, I’m getting off track here. This bike sucked. It was ugly, slow, had weak gas tank threads, bad reliability and did I mention that it was slow? About the only thing that was good was the suspension but then again, slow bikes always have good suspension right?

Back to your regular scheduled GP Classic Steel column…

|

|

Oh so close: In 1989, Kawasaki made major strides in two areas, but dropped three ball on the most important one. The ’89 KX was the best handling and best suspended KX ever, but burdened with a lethargic motor and old-school looks. It was the least sexy in a sexy field and the least fun in a class where fun was the name of the game. |

In many ways, the 1989 KX125 was the anti-Kawasaki. It finally fixed all the handling and suspension problems that had plagued them for the better part of a decade, but it dropped the ball on the one thing they did right – power. The new KX boasted great performance numbers, but those dyno reports were a paper tiger. In the real world, the KX was smooth and easy to ride, but too mellow to be any fun. It lacked the bark of the RM and YZ and the high rpm rush of the Honda. It was a nice and pleasant, but uninspiring. It had excellent handling and the best suspension, but the least verve of any of the 125’s. In the 250’s or 500’s, that might have been good enough for the win, but in the “motor is everything” 125 class, just good enough was not going to get it done in 1989.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram – @TonyBlazier