The Bomber almost won everything in ’83 but his bike let him down

The Bomber almost won everything in ’83 but his bike let him down

I started shooting Motocross Photos in 1975 basically just because I liked to but then when I started showing some of the guys I knew who raced they would tell me, hey you should sell those, when I asked them “who would buy these?” they said we would we’ll buy them all. Those guys were true to their word and they bought every photo I took of them and that was the start of Buckley Photos. Since then I’ve shot a ton of local races around here in New England, I’d say 99.9% of the novices that have ever raced in New England have a Buckley photo of themselves hanging in their garage.

I also shot a ton of nationals and supercrosses X Games Gravity games road races GNCC’s a little bit everything over the years traveling around the country shooting for almost every motorcycle magazine in the world I guess as well as shooting for almost every motocross clothing and accessory company in America. Want to order a classic print or something else? Go to buckleyphotos.com and we’ll hook you up. Thanks for reading- Paul Buckley

|

|

This 1983 RH250 of Mark Barnett carried the fuel in a alloy tank below the seat and housed the airbox in a dummy gas tank. Perhaps a bit too ahead of its time, the team riders actually did not like this design in 1983. Ironically, a version of this layout would make its way onto Cannondale and Yamaha production machines a few decades later. |

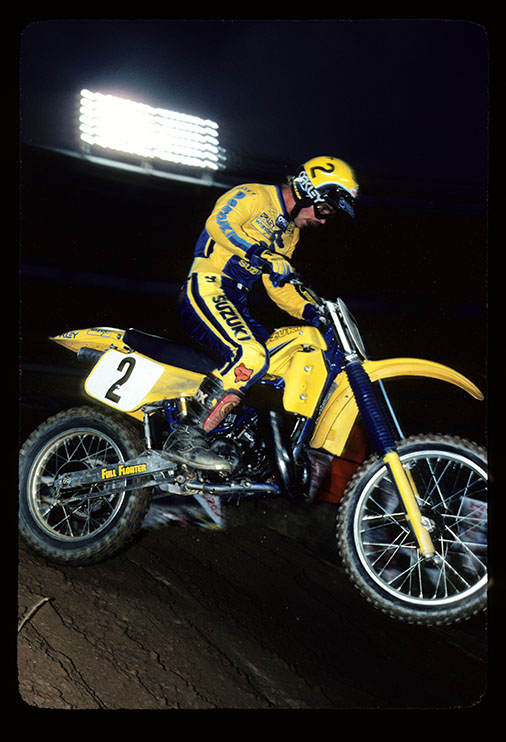

Blazier: For this week’s MX Captured, we have a couple of classics from the golden era of works bikes in America. These pictures from the Buckley Archive were taken at the 1983 running of the Atlanta Supercross and they capture both one of the greatest riders of the era and one of the most exotic machines from this exciting time in motocross.

By 1983, Honda was really starting to flex their impressive engineering and economic power with some of the most remarkable Factory machines ever built. Dual-disc brakes, cartridge forks, low-slung fuel cells, power-valved motors and handmade Monocoque subframes were all common on the ultra-trick Hondas. At the same time Honda was making its big push for motocross dominance, the rest of the Big Four were struggling to keep things afloat in the face of an economic downturn both in America and Japan. Without a massively successful automotive business to fall back on, it was difficult for manufacturers like Yamaha and Suzuki to keep pace with Big Red.

As a result, the other brands started to pull back on their racing budgets in the early eighties. This left proud brands like Suzuki playing catch up in divisions they had dominated only a few years earlier. In 1980 and 1981, Suzuki had roosted to victory in the Supercross and National series, but by 1982, the tide was beginning to turn. Honda’s revolutionary RC250’s set a new bar for trickness in ’82 and stole away Suzuki’s 250 Supercross and National title.

|

|

Today, Mark Barnett is best known as professional track builder, but in the early eighties the Bomber was recognized as one of the fastest men in America. A winner of three consecutive 125 MX titles and the 1981 SX championship, Barnett was admired for both his incredible fitness and blazing speed. |

For 1983, Suzuki looked to fire back with some advanced motocross technology of their own. Their new works RH250 would take Honda’s drop-tank concept and go one-step further, actually placing the fuel cell below the rider where the airbox normally resided. It was believed that by lowering the gas tank and its heavy fuel, the bike would be more responsive and better handling. This also meant relocating the airbox to the place where the gas normally resided. While this has actually turned out to be a benefit on modern four strokes like the new YZF’s, on of a carbureted two-stroke, the value of this configuration was more dubious.

The more convoluted intake tract demanded by airbox relocation actually hindered airflow and Suzuki’s team riders did not care for the bike’s unconventional handling feel. While certainly innovative, the design was considered a failure and quickly shelved by the race team in favor of a more conventional design. Maybe the trickest Suzuki seen in America since the heyday of Roger DeCoster and Joël Robert, the 1983 RH250 remains a curiosity from the most interesting era of American motocross.

Matthes: Blaze, the Bomber was my favorite rider growing up. I rode Suzuki 50’s and 80’s and therefore, Bomber was it. Well, also Ross Pederson because he ruled Canada. One of the things people don’t realize is that Mark’s bikes let him down a few times and kept him from winning more titles. He finished second in the SX championship two straight years and had DNF’s while the title winners (Hansen and Bailey) did not. In ’83 especially the title was his until his chain came off at, I think, Washington SX.

In the nationals there was no way the Suzuki was going to compare to the works Hondas of O’Mara or Kawasaki’s of Ward. He almost willed himself to a fourth straight title in the small class but it was time for the kids to start taking over. And the next year, in ’84, Mark moved up to the 250MX class and found himself again with a bike that wasn’t very good. Just the fact alone that Suzuki was juggling tank-in-the-airbox bikes and then going back to the normal configuration tells you that they were as confused as anyone. Barnett hated the factory RM250 and at one point went back to a production bike which was very strange back in those days.

Alas, 84 he was out at Suzuki and for ’85 he signed with Kawasaki and actually won a supercross but by ’86 he was retired. Bomber went from being one of the very best riders in the sport in ’83 to out of it two years later. It was a little nutty back then for sure. Then Bomber came back in 1989 for TUF Suzuki (he was only 29 years old by then or something) and I refuse to talk about this or remember anything about it.