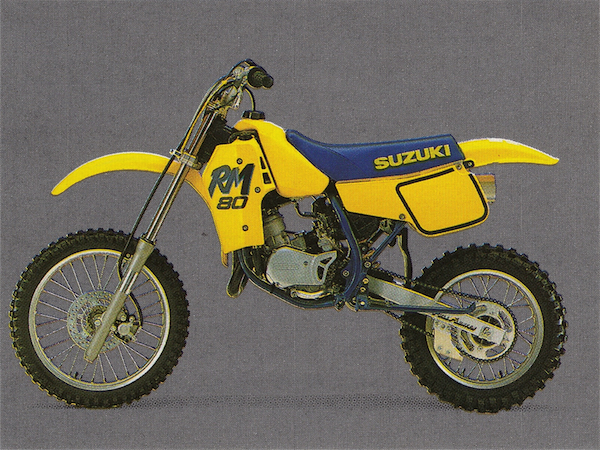

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the awesome 1989 Suzuki RM80.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the awesome 1989 Suzuki RM80.

|

|

In 1989, Suzuki shocked the minicycle world with a 80cc machine that ran like 250. The new RM80 barked to attention like a bike twice its size and pulled with authority over the broadest range ever to seen in the mini class. |

Today, the 85cc class is the last bastion of two-stroke supremacy in motocross. Once upon a time, the sweet smell of castor bean-oil and raspy melody of a smoker at full tilt rang through every track in America. Now, that smell and sound is a welcome respite from a world of blatting thumpers. For anyone over the age of thirty, that two-stroke melody is a touchstone to a simpler and more mullet-friendly time.

|

|

One of the pioneers of the Japanese mini motocross movement, Suzuki had offered pint sized racers going back to early seventies with their TM-75 Mini-Cross. In 1977, Suzuki upped the ante with their all-new RM80 (1978 model pictured). More serious and race-ready than the old TM, the RM80 would remain one of the most competitive machines in the mini-cycle class for the next three decades. |

The fact that the 85cc mini-crosser still exists at all is actually fairly remarkable. In 2007, Honda declared a Jihad on all things two-stroke and vowed to eradicate any and all of the oil-burners from their lineup. The resulting CRF150R was the first shot in what many feared would be the next wave of four-stroke domination. Thankfully, that anticipated extermination did not come (yet), and today (in spite of a decade of YZ150F rumors), the CRF remains the only four-stroke in the class.

|

|

While the 1989 RM80 looked largely the same on the outside, below that plain-Jane exterior beat the heart of a thoroughbred. |

In the mini classes the two-stroke’s simplicity, value and remarkable power-to-displacement advantage have (up to now at least) outweighed the broader power curve of the thumper. For mini dads everywhere, this has kept the sport accessible both in terms of cost and complexity. For any sport to survive it needs keep young people involved and with the price of new bikes creeping ever skyward, the role of the cheap and easy to work on two-stroke is more vital than ever.

|

|

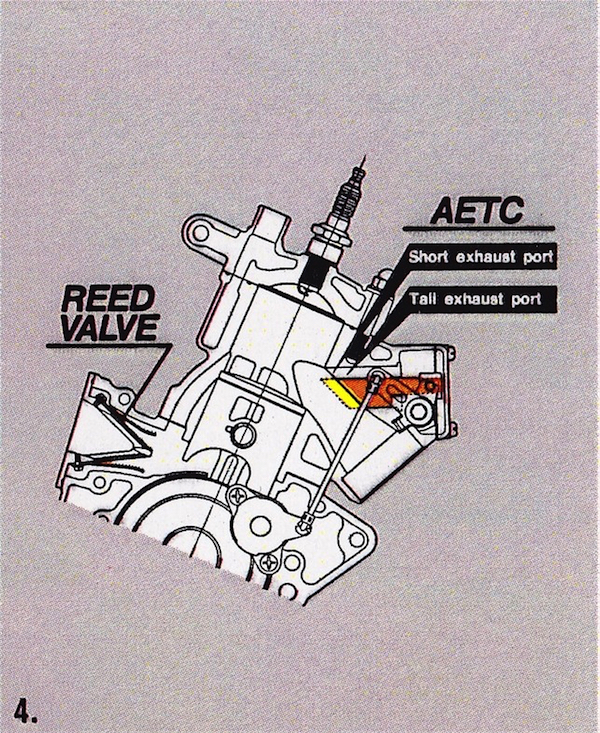

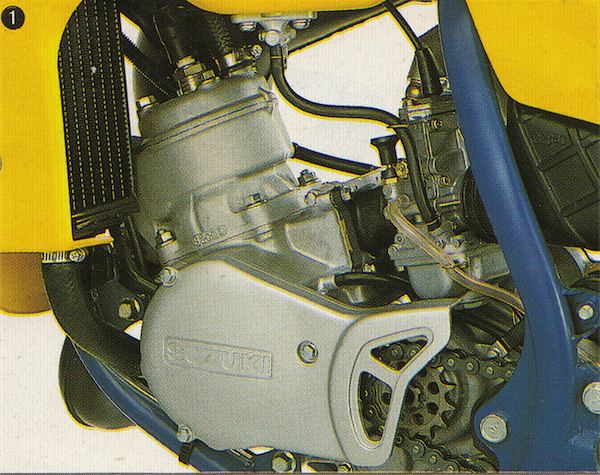

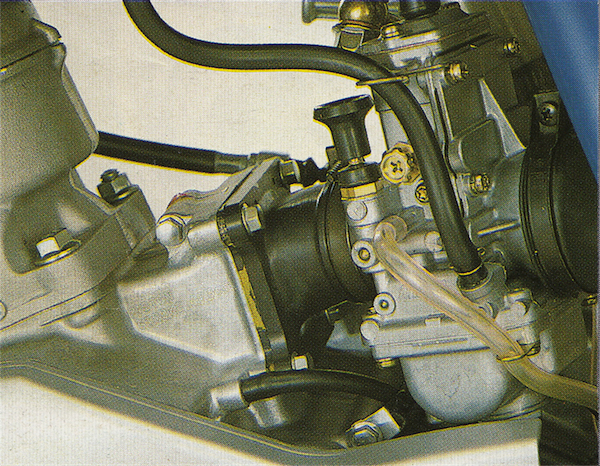

For 1989, Suzuki dialed up an all new mill for their pint sized racer. The liquid-cooled two-stroke single displaced 82cc’s and featured a case-reed design for better intake flow. Adding to the power picture was Suzuki’s first implantation of a “Power Valve” in its 80 class machine. |

In the beginning, mini racers had often been backyard specials cobbled together from various pieces never intended to work together. These bikes required a skilled hand to fabricate and talented pilot to make the most of their often modest performance capabilities. As the sport became more popular in the seventies, however, the major manufacturers began to see that there was a market for a factory built mini racer. In 1974, Yamaha would introduce their YZ80 for the first time and send seven-year-olds everywhere scurrying in search of a paper route. When Suzuki followed that up in 1976 with their power-reed equipped RM80, the race for 80cc supremacy was on.

|

|

Suzuki’s AETC (Automatic Exhaust Timing Control) featured two guillotine valves that slid up and down based on the engine rpm. By varying the exhaust port height with these valves, Suzuki was able to provide the little RM80 with the widest powerband ever seen on a mini class machine. |

Much like today, Honda’s entry into seventies mini-class racing was actually a four-stroke. At the time, their little XR75 (later XR80) was actually a viable racing choice and Honda mini Factory rider Jeff Ward waxed more than a few smoker mounted pilots on the little thumper. As mini-cycle technology progressed, however, the little XR became less and less competitive versus the competition.

By the end of the decade, the mini class had become important enough that both Kawasaki and Honda felt they needed introduce full-blown 80cc two-stroke racers of their own. The new CR80R and KX80 were 5/8ths scale replicas of their big brothers and featured powerful racing-focused two-stroke motors and long-travel suspension. With the addition of the CR and KX, the Big Four each had a little skin in the 80cc game and the competition for mini-cycle Top Gun became more intense than ever.

|

|

Suzuki’s new RM80 mill pumped out an amazing spread of power from its 82cc’s. Torque off the line was excellent and there was no need to fry the clutch out of turns like a typical 80. After its ample bottom end, the RM climbed into a hard hitting midrange and strong top-end run out. In 1989, this was the ultimate mini class power plant. |

While the CR, KX, RM and YZ 80’s were all a quantum leap ahead of anything available to mini racers only a few years before, they continued to lag behind the technology found on their full-size stable mates. Items like disc brakes, liquid cooling, and adjustable suspension would eventually make it to the 80 class, but it would be a year or five behind the big bikes.

By 1988, all the 80cc racers were sporting high-horsepower liquid cooled motors and disc brakes at the front (only the Kawasaki offered a disc for the rear). All the machines lacked the high-tech cartridge forks found on the full size machines and made due with non-adjustable damper internals from the late seventies. In the rear, the red, yellow, green and white mini-crossers faired a little better, with shrunken down versions of the big bike’s single shock rears that at least offered some form of external adjustability. While it may have been a stretch to call the mini-cycle crop of 1988 cutting edge, it was no exaggeration to call them potent racing weapons.

|

|

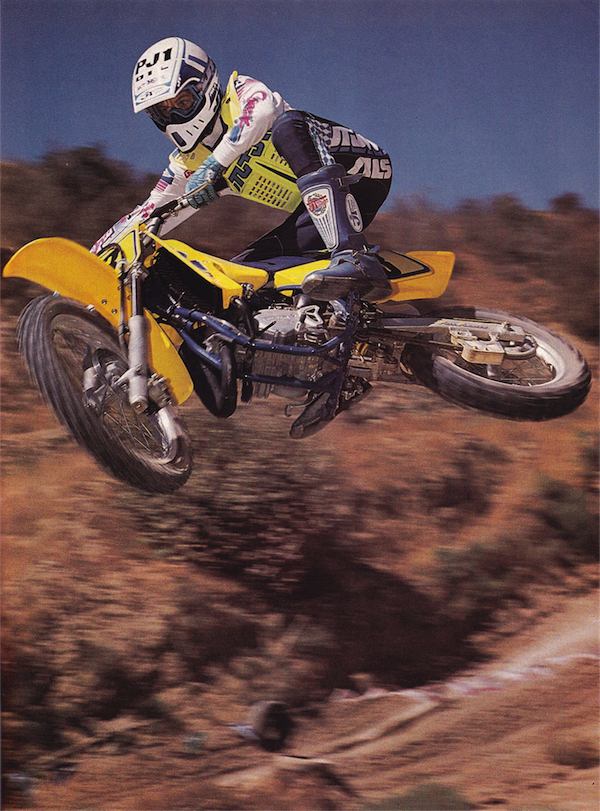

Full Tilt Boogie: Unlike a typical mini, the ’89 RM80 could be torqued out of turns and finessed through tricky switchbacks. With its wide powerband and ample hit, the RM was the easiest 80 to go fast on in 1989. |

For 1989, Suzuki looked to finally break free from its mini-class rivals with an all-new power plant. In 1988, the RM80 had been an excellent racing mini overall, but it was saddled with a hard-to-ride and peaky mill. The little Zook offered excellent handling manners and the best suspension in the class, but less skilled riders found it hard to use and it gave up several horses to the rocket-fast Honda.

|

|

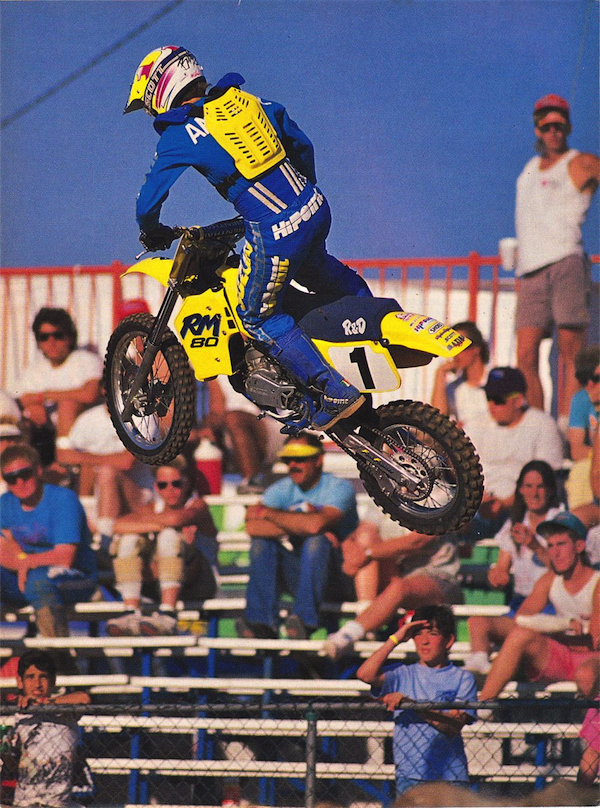

In the late 80’s, Suzuki had a powerful presence in the mini classes. Factory riders like Buddy Antunez took the RM80 to many championships on his way to the pro ranks. |

With the new RM80K, Suzuki was set to put those underpowered days in the rearview mirror once and for all. On tap was an all-new 82cc mill that adopted the case-reed induction common to the fastest 125’s of the day. This intake design offered better flow characteristics and typically, more top-end power than a traditional cylinder-reed configuration. Adding to the power package for 1989 was an all-new exhaust and the addition of Suzuki’s AETC (Automatic Exhaust Timing Control) for the first time. This was big news in 1989 and marked the first implementation of a variable exhaust port “Power-Valve” in the mini class.

|

|

Excellent and roomy ergonomics made the RM80 one of the best choices for the aspiring mini racer in 1989. It and the Honda offered the most room for mini pilots trying to eke out one more year of eligibility on the 80. The pint sized Yamaha was favored by small riders, while no one particularly liked the odd seat-bar-peg relationship on the KX80. Dirt Bike Photo |

In 1984, Honda had offered their CR80R with a scaled down version of their ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) system. The ATAC was Honda’s first attempt at a variable exhaust device and it tried to increase torque by adjusting the CR’s head-pipe volume at low-rpm’s. This marked the first time anyone tried one of these powerband-widening gizmos in the 80cc class. Unfortunately, the original ATAC met with tepid acceptance in the marketplace and was gone off the CR80R by 1985.

|

|

The new 32mm Mikuni Flat-Slide “Slingshot” carburetor employed on the RM gave the bike excellent throttle response and a snappy delivery. |

In 1986, Suzuki added their own version of a Power-Valve to their RM125 and RM250. This early version of the AETC worked very similarly to Honda’s ATAC, by adding a small sub-chamber to the exhaust manifold. This original AETC design worked no better on the RM’s than it had on the early CR’s and by 1987, Suzuki had moved on to a more advanced system similar in theory to Yamaha’s YPVS. This second generation AETC did away with the exhaust sub-chamber and replaced it with a pair of sliding guillotine valves that slid up and down to vary the height of the exhaust port based on engine rpm. At low rpm, the valves were down to lower the port height and increase torque. At high rpm, a centrifugal-ball governor slid the valves up to open the exhaust port and increase flow for better top-end pull.

|

|

Braappp: A twist of the right wrist was all that was necessary to get the ’89 RM80 on the pipe and ripping. Dirt Rider Photo |

For 1989, the little RM80 got the AETC treatment for the first time and overnight it changed what people could expect from an 80cc machine. Right off idle, it snapped to attention like no mini had any right to do. Power was strong down low and there was no need to fry the clutch out of turns like you would a typical 80. Past the beefy low-end, there was a strong midrange hit and substantial top-end run out. Power was incredibly broad for a mini and the powerband actually mimicked a 250 more than your typical 80. It was leaps and bounds better than the hard-to ride ’88 RM and far and away the best motor in the 80 class.

|

|

Airtime was quick and easy with the RM’s powerful motor, sharp handling and roomy ergos. Dirt Bike Magazine Photo |

In terms of outright thrust, the only competition for the might mini RM came from Honda’s rocket-fast CR80R. The CR lacked the RM’s Power-Valve and it showed in the red machine’s narrow, but potent spread of ponies. Down low, the CR was nothing but bog, and a quick stab of the clutch was required to get the Honda going. Once it hit the midrange though, it was hang on tight and keep grabbing gears till you were out front. Nothing hit as hard, or pulled as far as the blood-red Honda. It was hard to keep on the pipe and tricky to manage, but oh was she fast.

|

|

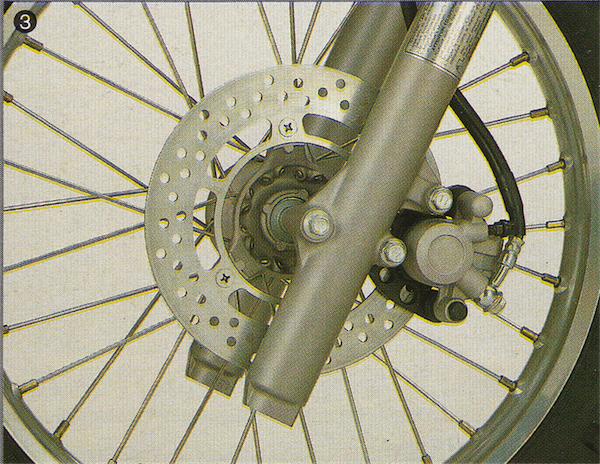

In 1989, none of the mini-cycle class offered the performance and adjustability of the latest cartridge forks found on the full size machines. On the RM, a non-adjustable set of 35mm Kayaba’s offered 10.8 inches of plush travel. This was up 2mm in diameter over 1988 and gave the RM a planted feel and sharp response in the turns. Even without external adjustment, the RM’s KYB’s offered the best ride in the 80 class. |

Behind the broad and powerful RM and rip-snorting CR, we had the midrange-and-up KX and novice friendly YZ. The KX80’s power spread was actually similar to the CR80R, but with a milder hit and less outright power. As for the Yamaha, power was focused over a very narrow spread with little usable thrust above or below the midrange burst. It offered the least explosive power in the class and catered more to the beginners than Bradshaw types.

|

|

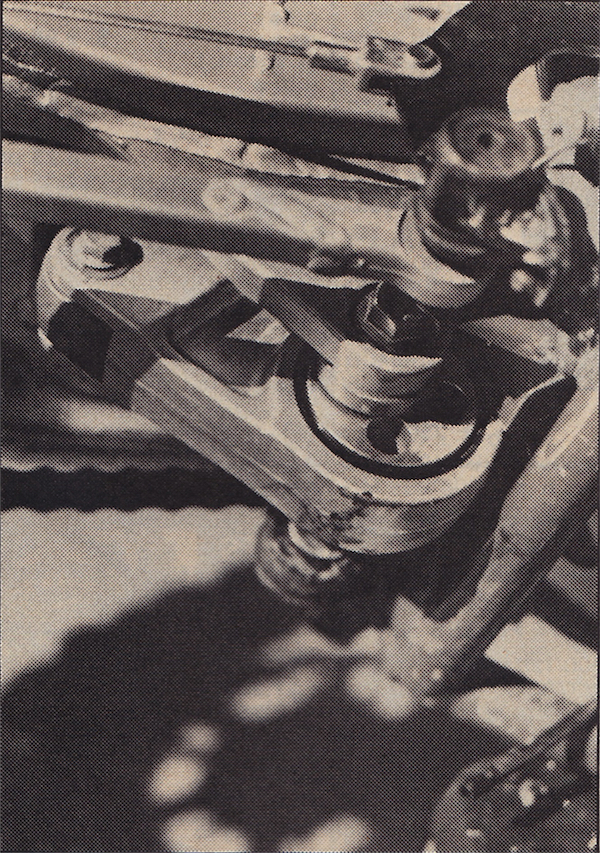

In 1989, Suzuki offered the best rear suspension on the mini-cycle class. The excellent Full-Floater rear punched out 10.8 inches of travel and offered both compression and rebound damping adjustments. The ride was extremely plush and well set up for all but the fastest mini pilots. |

In the suspension department, the RM80 was once again the class of the field. New Showa forks for ’89 upped the diameter of the sliders from 33mm to 35mm and upped travel slightly. The new beefier sliders improved steering precision and feel on big hits, while updated valving provided an ultra-plush ride. The non-cartridge internals offered no external adjustability, but most mini riders found the action excellent out of the box.

In the rear, the ’89 RM80 retained the eccentric-cam Full Floater linkage that had been universally panned on the RM125 and RM250 and mated it to new Showa shock that offered both compression and rebound adjustability. Interestingly, the eccentric-cam linkage did not seem to suffer the same stiction issues on the 80 as it had on the bigger machines and no one complained about its action. In terms of performance, the RM was once again at the top of the class with excellent control and a plush ride. The stock spring was sufficient for anyone below the expert class and most riders could find a satisfactory setting within its range of adjustment.

|

|

In 1986, Suzuki ditched their award-winning original Full-Floater design in favor of a new eccentric-cam style linkage. The new design was plagued with stiction issues and replaced after one year on the RM125 and RM250. Interestingly, the RM80 did not seem to suffer from the same maladies and continued to use the design well into the next decade. |

In the overall suspension ranking, it was the RM by a wide margin over a confused and poorly set up field. Both the Honda and Yamaha suffered from suspension that was far too soft, prone to flex and badly under-damped. Any large jumps were met with a mighty thud as the forks and shock of both machines crashed to the stops. The marshmallow-soft forks on the Honda were of particular concern, as they dove severely under braking and compounded the Honda’s penchant for violent headshake.

|

|

Today, Suzuki’s amateur program is more or less nonexistent and the dominant days of Buddy Antunez (pictured), Travis Pastrana and Davi Millsaps are all but a distant memory. Hopefully the one time motocross power will regroup and make a push to rebuild their amateur program in the near future. Dirt Bike Magazine Photo |

At the opposite end was the KX, which did not bottom out, but was harsh and unforgiving at both ends. Small bumps were transmitted right to Jr.’s wrists and the KYB shock had an annoying habit of whacking the rider in the backside on sharp impacts. In 1989, only the RM80 was capable of offering a plush ride and decent control.

|

|

If there was one chink in the ’89 RM’s armor, it was this outdated and underpowered rear binder. Even by drum standards, this was a poor excuse for a rear brake. |

In the handling sweepstakes, the RM was once again at the head of the field. Turning was sharp and crisp with the beefy new forks, and it tied the Honda for best turning. Unlike the Honda, stability was excellent on the Zook was far less terrifying at speed than the CR. The KX was also stable at speed, but it was less precise in the turns and liked to crawl out of berms if the rider was not totally committed. In last was the under suspended Yamaha, which was vague in the turns and a handful in the rough.

|

|

The other half of Suzuki’s amateur powerhouse in the late eighties was Phoenix, Arizona’s Jimmy Gaddis. After a successful amateur career, Gaddis would go onto capture two Arenacross titles and the 1993 West Coast 125 Supercross title. Dirt Bike Photo |

Ergonomics were another win for the RM, with best ‘big-bike” feel for larger riders in spite of its somewhat dated plastic. Honda was second a sleek and more modern-looking layout than the RM, but a slightly stinkbug feel exacerbated by the wimpy forks. In third sat the KX, with up-to-date looking plastic, but an odd bar-seat-peg relationship that had most riders complaining of a cramped feel and funky bar placement. In last was once again the YZ80, with ergonomics suitable only for the smallest of mini pilots.

|

|

While the single-piston disc front brake on the RM was better than its pathetic rear binder, it was still nothing to write home to mom about. Both the Honda and Kawasaki’s front discs out performed it by a substantial margin. |

In the details department, the RM was solid, but not class leading. Braking upfront was adequate from its single-piston Nissin caliper, but the rear binder was considered grim even by drum standards. It was last of the three drum brakes in the class and a quantum leap behind the Kawasaki’s powerful rear disc stopper. Both the finicky cam-linkage Full Floater and loose-ball steering head bearings made servicing the RM a pain and it lacked the zoot-capri removable subframe of the Honda. On the plus side were the RM’s roomy ergos and trick rebuildable alloy silencer, which was both excellent performing and the quietest unit in the field.

|

|

The Champ: The AETC-equipped Suzuki RM80 was a game changer in 1989. It was blazing fast, yet still easy-to ride. This was something never before seen in the pin-it-to-the-stops mini-class and it gave the RM and advantage no other 80 could overcome in 1989. |

In 1989, Suzuki finally brought the mini-cycle class into the modern era with a case-reed, power-valved rocket ship of an RM80. It barked to attention down low, ripped through the middle and kept right on pulling until the yellow missile was out front. It was both blazing fast and easy to ride, a combination never before seen in a full-race 80cc machine. With its excellent suspension, crisp handling and burly motor, the RM80 was the class of the field in 1989.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier