For GP’s #100, I thought we would take a look back at one of the most influential machines in motorcycling history – the 1968 Yamaha DT-1 Enduro.

For GP’s #100, I thought we would take a look back at one of the most influential machines in motorcycling history – the 1968 Yamaha DT-1 Enduro.

|

|

In 1968, Yamaha introduced a machine that would change the face of off-road riding forever – the DT-1 250 “Enduro”. The Dit-One was inexpensive (nearly half the cost of the pricy Euros), reliable (at a time when bikes were pretty much expected to break down) and more capable than any Japanese bike that had come before it. |

(Matthes note: ONE HUNDRED GP CLASSIC STEEL’S BRO!!!! That’s awesome, Blazier does such an awesome job with this column and he really puts a lot of work into them as well. Check out his archive to see if one of your favorite bikes are in there and thanks for reading this and other Pulpmx Stuff. And oh yeah, thanks to Blaze for the hard work!)

What if I told you that the most important machine in American motocross history was not a thoroughbred race bike, but actually a lowly dual-sport? That is right; Ryan Villopoto, James Stewart and Chad Reed owe their mega-bucks pay checks not to some sexy two-wheeled Ferrari, but to a simple, inexpensive and unassuming piece of everyday transportation. A machine so well conceived and so perfect for its time, that it ignited an off-road revolution.

|

|

In 1968, Yamaha hired Don Jones and his sons Gary and Dewayne to help develop the new DT-1 for racing. The team would be the driving force behind Yamaha’s first foray into motocross in America and the architects behind the bike that would eventually become the YZ. |

In the early 1960’s, off-road motorcycles basically fell into one of two categories: fragile and expensive purpose built racers, or street bikes suitable for gravel back roads and little else. At the time, off-road pleasure riding was a uniquely American endeavor and the thought of a bike that could do well both off-road and on was an alien concept to the manufacturers from Europe and Japan. Over there, wide-open spaces were rare and most off-road riding had to be done on closed courses.

|

|

Pick your poison: In the late sixties, off-road machines fell into one of two categories: full-bore racers (like this beautiful ’67 Husqvarna) or mildly massaged street machines with up-pipes and adventurous sounding names like “Hustler” and “Trail Boss”. For the hard-core enthusiast, these European thoroughbreds offered impressive performance, but their steep cost, finicky nature and spotty parts availability made them a hard sell to weekend warriors. |

As a result, the bikes from Europe tended to be very specialized. Across the pond, Motocross was popular, and their off-road offerings were far more performance focused than the average desert rat was looking to live with. They had light and powerful two-stroke motors, cutting edge suspensions, and price tags to match. The Husky’s, CZ’s and Montesas of the Old Country all offered blistering performance, but they were difficult to get parts for, finicky to own and hard on the wallet.

|

|

At the other end of the spectrum, you had bikes like this 1967 TC250 from Suzuki. Little more than a street bike with trials tires and a high-mount pipe, these “Scramblers” were suited for venturing onto gravel roads, and little else. |

Another option for off-road enthusiasts of the day was the big British twin. These Triumph and BSA machines were light by street bike standards and could be made to work decently off-road with a little elbow grease and ingenuity. By stripping all their street running gear and adding some knobby tires, these bikes could be turned into pseudo race machines known as “desert sleds”. In the sixties, these thundering 350-pound monsters were actually popular and a common alternative for desert racers on a budget.

|

|

For the truly adventurous sixties off-road enthusiast, you had the “desert sled” route. Starting with a twin-cylinder Triumph or BSA, these hairy-chested macho types would strip off all the street legal nonsense, bolt on a set of headers (mufflers are for pussies), throw on some knobbies and hold on tight. Crude, course and cobby, these burly behemoths were a handful for all but the heartiest of desert rats to tame. |

In 1966, one of these racers was a Yamaha employee by the name of Dave Holeman. As a motorcycle enthusiast and a big fan of desert racing, Holeman looked at the wide open spaces of the American West as a huge opportunity for his employer.At the time, the Japanese had very little presence in the off-road riding arena. Most of their offerings were lackluster performers, with impressive sounding names like Big Bear Scrambler. These “scramblers” were in fact, little more than street machines with trials tires and “up” pipes. On road, they worked well, but off road, they were a disaster.

|

|

Prior to the DT-1, this was what passed for a dual threat in Yamaha’s stable. The Big Bear Scrambler 305 sounded impressive, but fooled no one with its pseudo dirt bike styling and porky 380 pound fighting weight. |

In the spring of 1966, Holeman talked a fellow Yamaha employee by the name of Jack Hoel into accompanying him to some desert racing events. An accomplished scrambles racer in his own right, Hoel was the son of Pappy Hoel, the founder of the Black Hills Rally. After attending a few of these events, Hoel and Holeman formulated a plan to get Yamaha in on the off-road market. One look at the crude and cobbled together assortment of machines being raced across the Mojave was enough to convince them that there was a demand for an inexpensive bike capable of being raced with minimal modification, and then ridden to work on Monday. Best of all, as the head of research and development for Yamaha USA, Hoel was actually in a position to make it happen.

|

|

When developing the motor for the DT-1, Yamaha went with a design that favored usability over outright performance. The 246cc two-stroke single featured an innovative five-port design developed by Yamaha’s road-race program that allowed for an ultra-wide spread of power. With the stock five-speed transmission, the DT-1 could be happily plonked around all-day at 5mph and then ridden home at a comfortable 65mph. Power was extremely smooth and linear, with ample torque and none of the loading up common to high performance two-strokes of the day. |

At this time in history, Yamaha was far from the racing powerhouse they would grow into in the 1970’s. While the Yamaha Corporation itself dated back to the 1880’s, the Motors division was barely a decade old in 1966. They had introduced their first production motorcycle in 1955 (a 125cc DKW rip-off dubbed the YA1) and built their success on producing small and inexpensive two-stroke runabouts.

|

|

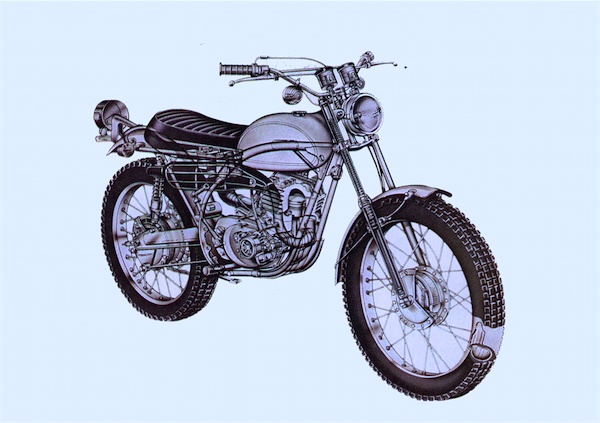

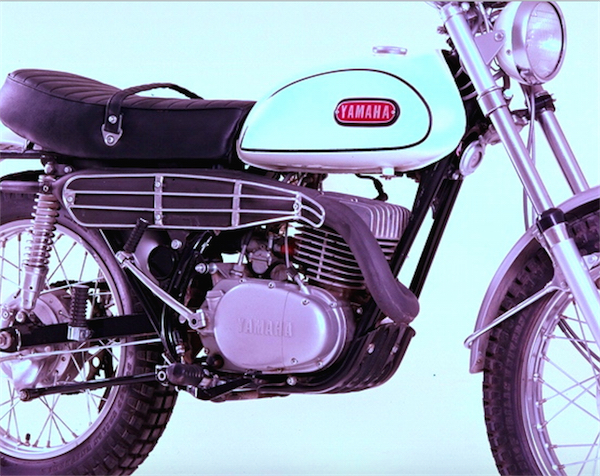

What set the DT-1 apart from the hundreds of models that had come before it was that Yamaha made sure to make it a good dirt bike first, and then worried about the street gear later. |

Three years after rolling the first YA1 off the production line, Yamaha had made its initial foray into international “off-road” competition by entering the 1958 running of America’s most prestigious motorcycle racing event – the Catalina Grand Prix. Held on the small resort island of Catalina off the coast of Southern California, the Grand Prix offered a unique course that included city streets and mountainous gravel roads. Riding a modified twin-cylinder YD250 two-stroke street bike, Fumio Itoh piloted his Yamaha to a very respectable sixth in the race.

|

|

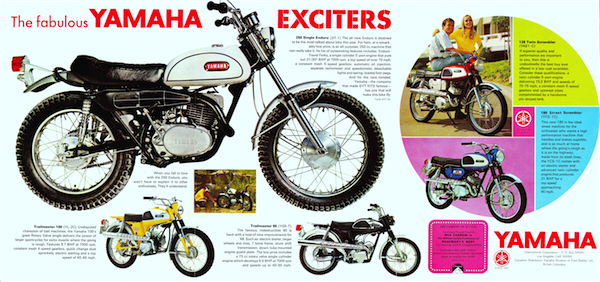

The 1968 Yamaha line-up was full of exciting names like Scrambler and Trailmaster, but only one, “Enduro” would become synonymous with a whole new type of motorcycle. |

As Yamaha entered the 1960’s, their racing interests focused on road racing. Both Suzuki and Honda had enjoyed success on the world stage with their high revving small-bore road racers and Yamaha was quick to jump in with both feet. At the time, motocross was not even in the conversation in America and mearly a curiosity in Japan. The grueling sport was popular in Europe, but all but unheard of outside the Old World. As the decade progressed, however, the Japanese became more interested in expanding their racing efforts.

|

|

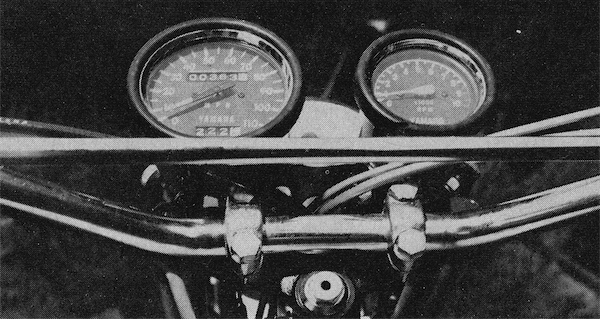

One of the great features of the DT-1 was its remarkable versatility. Lights, turn signals and full instrumentation were standard and designed from the factory to be easily removable for competition use. |

|

|

A strong double downtube steel frame and light overall weight gave the DT-1 exponentially better handling than any previous dual-sport from Japan. Both turning precision and feel were good for its time, but the bike’s short wheelbase could make it a handful at high speed. |

|

|

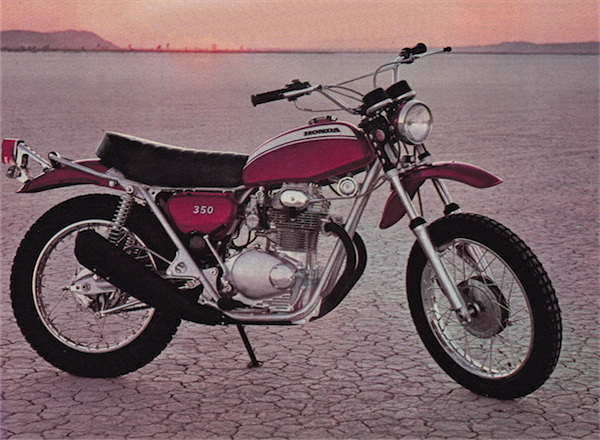

Attack of the Clones: After the blockbuster success of the Yamaha DT-1 (selling upwards of 50,000 a year) the rest of the Big Four were quick to jump on the “Enduro” bandwagon. Bikes like this Honda SL350 were snapped up in droves by a public looking for fun, reliable and inexpensive two-wheeled transportation. |

In America, Hoel and Holeman looked at this increased interest as an opportunity to implement their vision for a truly dirt worthy Yamaha. When Hoel approached the brass at Yamaha, they liked the idea and green lit a program to research a new dual-purpose machine, specifically for the American market.

|

|

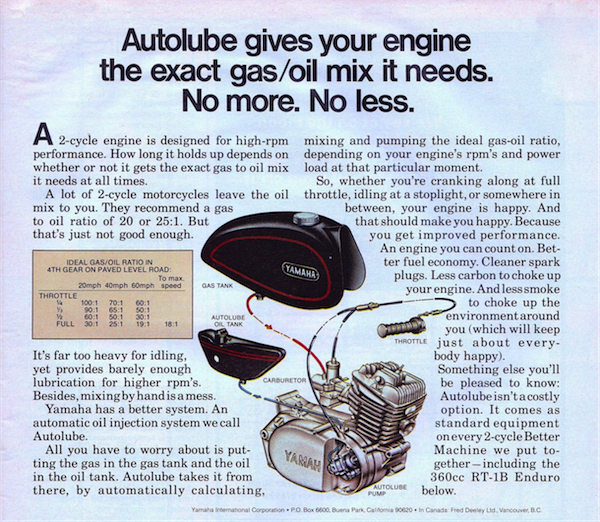

Originally debuted in 1964 on their Santa Barbara street bike, the Yamaha Autolube injection system took the muss and fuss out of two-stroke operation. There was no longer a need to mix gas and oil and the Autolube system automatically adjusted the mix ratio to suit conditions. |

|

|

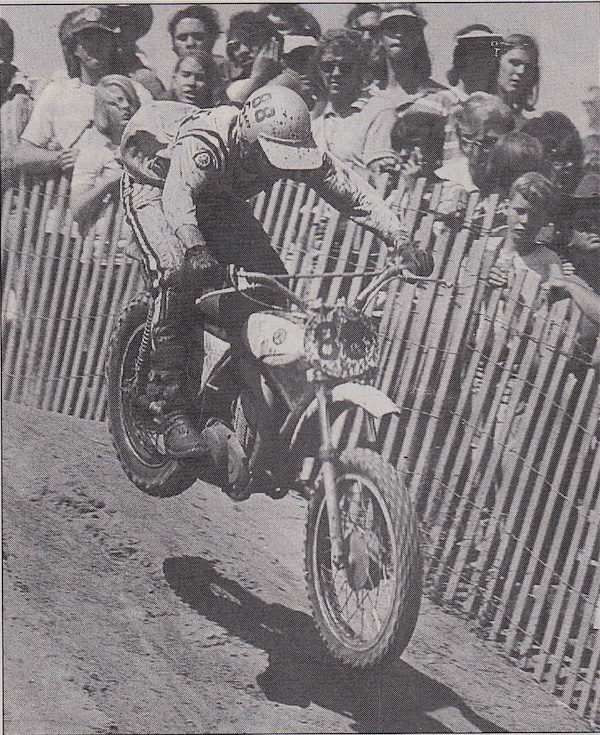

In 1972, Gary Jones campaigned a highly modified DT-1 to America’s first 250 National Motocross title. |

Once they got the go-ahead, the first thing that Hoel and Holeman did was buy every dual-purpose machine available at the time. They took apart Bultacos, Greeves, DKW’s and Montesas and studied what made each tick. In the end, the team ended up with a cobbled together conglomeration of Bultaco, Montesa and Yamaha parts. It did not run, but it would give the engineers a good working sketch of where they wanted to go with the design. Once they had the rough outline of what would eventually become the DT-1 mocked up, they approached Hamamatsu for their feedback.

|

|

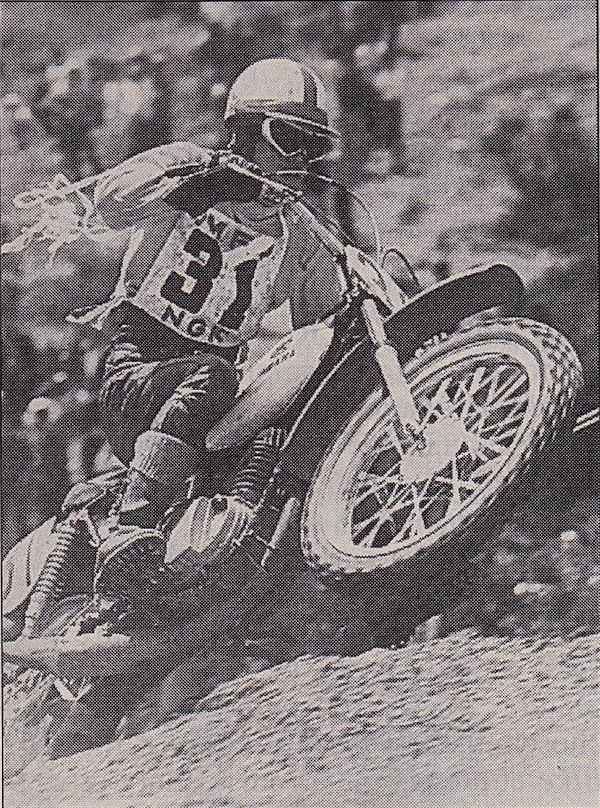

Perhaps no machine is history introduced more riders to the joy of racing that Yamaha’s ubiquitous little Dit-One. With minimal modification, the DT-1 could compete in motocross, dirt track, cross country, desert racing and even enduros. |

Yamaha was so impressed with the mock up that they immediately flew six engineers to California from Japan to work on the project. The team hacked, welded bent and fabricated away on the mock up and sent ongoing reports back to Japan. After a few weeks testing in the California desert with Hoel and Holeman, the engineers flew back to Japan with tales of the crazy Americans and their desert bomb runs.

|

|

The DT-1 came extremely well finished for its time. Spring-loaded pegs were an unexpected luxury in ’69, as were the trouble free electrics and nearly indestructible motor. One interesting feature unique to the time was the universal transmission shaft that exited both sides of the cases. This allowed riders accustomed to right-hand shifting European machines to reverse the placement of the brake and shifter. |

Two months later, two crates arrived from Japan with the first two prototype DT-1’s ready for testing. Yamaha USA enlisted desert racing star Neil Fergus to shake down the new machine and set about making the bike a reality. Fergus and fellow tester Gary Griffin spent the next six months pounding prototypes to dust in the California desert, while Hoel and his team took detailed notes on what worked and what broke. By the fall of ’67, the team believed they had the formula nailed, and Japan set about bringing the all-new Yamaha DT-1 250 Enduro to market.

|

|

In Japan, Hideaki Suzuki campaigned a works version of the new DT-1 to victory in the ’69 All-Japan Motocross Nationals (note the missing Autolube injection on the engine cases) |

Right from the start, the enthusiast press knew Yamaha had something special on their hands. The DT-1 was truly an all-new type of off road machine. At $580, the new “Enduro” undercut its expensive European rivals by several hundred dollars and for that paltry sum; you got reliable electrics (something not found on most machines of the day), Autolube injection (a major innovation at the time), a powerful two-stroke motor, full instrumentation and quality throughout. Because the DT-1 was designed from the beginning to be a dirt bike, its performance off-road was a quantum leap better than anything else ever offered from Japan. The best from Europe were still a notch ahead, but the gap was no longer a cavernous gulf. On the road, the DT-1 was likewise a step down from a pure street bike, but far better once the pavement ended than any road bike in dirt drag.

|

|

Gary Jones on his ’72 race bike “Our bike was the basis for the ‘74 YZ, we made the very first one. We started with at DT-1, cut the frame, and lengthened some of the bars here and there. We moved the pegs back, lowered the engine down, flattened out and lengthened the swingarm. All of our spacers and bolts were titanium with holes drilled in them, sometimes using pins instead of nuts, and we trimmed down the fork castings to take weight out of it. We gave the bike back, as Yamaha was paying for us to do the work. We used to call that bike ‘A to Z’ because we had done everything from A to Z on it. When the bikes came back from Japan, A-Z became the YZ.” Motor Cyclist Photo |

|

|

In ads, Yamaha touted that the consumer would “discover the magic of Yamaha’s own Enduro-Travel Forks.” In reality, these Ceriani knock-offs were less than magic and actually left a good bit to be desired. Softly sprung and underdamped, they were fine for light off-roading, but unsuitable for competition. With a Webco fork brace and spring kit they became livable, but the really hot setup was a complete Ceriani or Betor front assembly. |

The DT-1 was the first bike to really nail that balance between dirt and street and gave birth a new idea: A good dirt bike makes a better street bike, than a street bike makes a good dirt bike. The DT-1 was attractive, reliable and with a little work, a capable race mount. Once the bike actually hit dealer’s floors in March of 1968, the little white beauties sold out immediately. The initial 8000 units flew off dealer’s lots and within a short amount of time, Yamaha was selling 50,000 DT-1’s a year!

|

|

By far the biggest deficiency of the stock DT-1was its grim stock shocks. Much like the forks, these units were adequate for trail riding, but badly underdamped for competition use. Anyone serious about racing the DT-1 was wise to pony up the cash for a set of Koni or Girling dampers. |

|

|

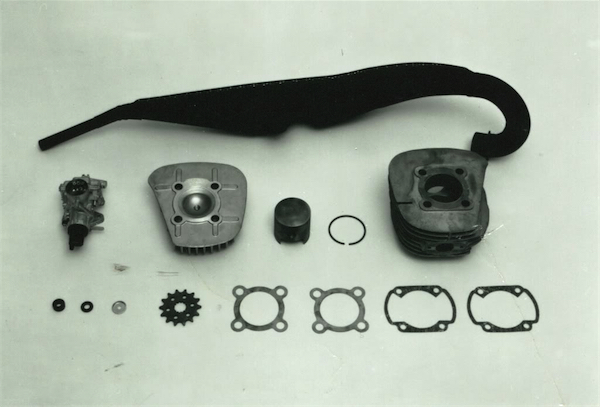

For those interested in racing their DT-1’s, Yamaha offered a power up kit that raised the advertised power output from a mild 21 horsepower, to a firing-breathing 30 ponies. Consisting of a new cylinder, head, single-ring piston, carburetor, gearing and pipe, the GYT (Genuine Yamaha Tuning) kit boosted forward thrust, but greatly narrowed the stock bike’s wide and easy-to-use spread of power. |

While the DT-1 was a revolution in many respects, it was not perfect. Power was decent for a trail mount or commuter, but not arm stretching by racing standards. The shocks were terrible, the forks mediocre and the handling twitchy at speed. Of course, due to the bike’s incredible popularity, the aftermarket quickly addressed all of these issues. Yamaha itself jumped on the bandwagon with a power-up package they called a GYT (Genuine Yamaha Tuning) Kit. The GYT kit was comprised of a high-performance cylinder, head, single-ring piston, carburetor and expansion chamber. The kit jumped the horsepower from a mild 21 to a fire breathing 30, but did nothing for the bike’s sub-par suspension and spooky high-speed stability.

|

|

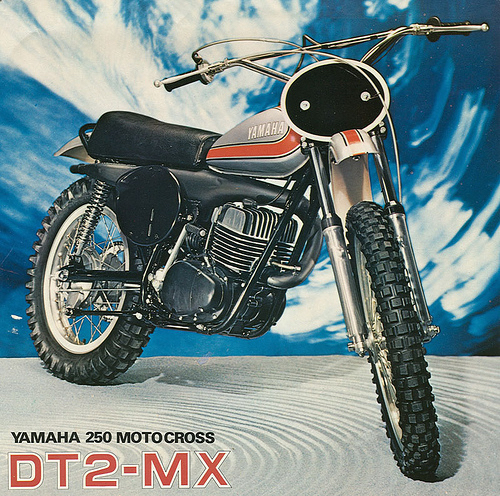

With the outstanding sales success of the DT-1 and its GYT Kit, Yamaha decided there was probably a market for a factory built DT-1 based racer. The result was the new DT-2-MX. The DT-2 ditched all the DT-1’s street froof, and bolted on all the go-fast goodies right from the factory. From these humble origins, would rise a motocross dynasty. |

|

|

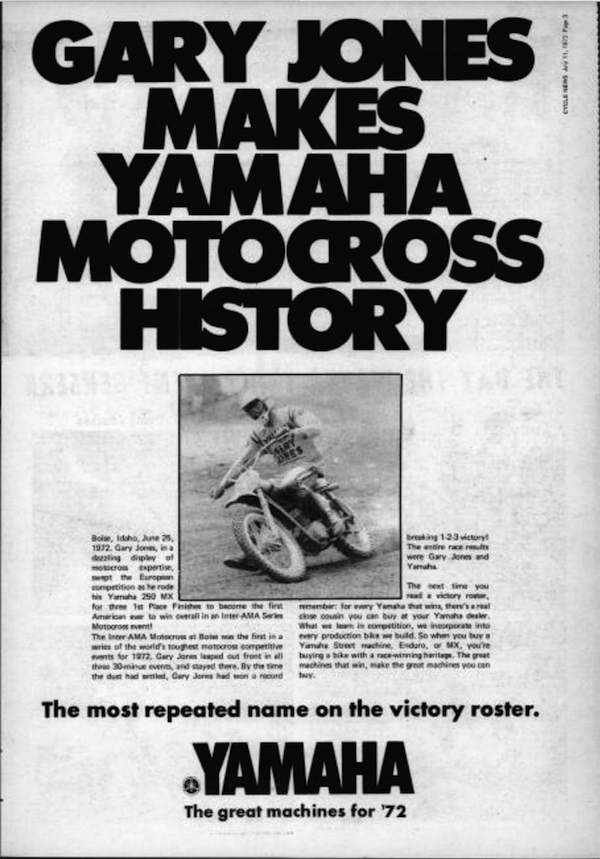

Gary Jones’ 1972 National Motocross title would provide an excellent PR opportunity for Yamaha new line of factory built motocross machines. |

The best things about the DT-1 were its anvil-like reliability, affordability and versatility. It was a bike that could be striped of its lights on the Saturday, raced on Sunday and then ridden to work Monday. It always started (no mean feat in 1968), looked great and didn’t kill your bank account. With the addition of some Girling shocks and a Webco fork kit, the little Dit-One could actually be a decent motocross racer. If you added an extended swingarm to tame its high-speed wandering, it could even be a decent desert mount. Ironically, the only discipline it was not particularly adept at was Enduro racing, where the stock bike was too tame and the kitted bike too rowdy.

|

|

Much of the development work done by Don Jones and his sons on the original DT-1 racer would make its way directly onto Yamaha’s first no-compromise motocross racer – the 1974 YZ250A. |

|

|

In 1968, Yamaha changed motocross history with their incredibly versatile DT-1 250 Enduro. In stock form, it was no hard-core racer, but it was inexpensive, reliable and capable of being turned into a competition machine with a few dollars and a little elbow grease. It was the bike that introduced a generation to the joys of off-roading and helped set in motion the dirt bike revolution we still enjoy today. |

In 1968, the DT-1 was a revelation, and within a few years Yamaha would have 60cc, 125cc, 175cc and 360cc versions of the bike for sale. It made racing accessible to an all-new generation of kids looking get into the exciting new sport of motocross. It was the right bike, at the right time and would kick off an explosion in off-road sales in the late sixties. A highly modified DT-1 (the genesis for what would eventually become the first YZ) would even take Gary Jones to America’s first National Motocross title in 1972. The Yamaha DT-1 250 Enduro may not have been blazing-fast, über-exotic or super-sexy, but no other machine in history has done more to further the growth of our sport than Yamaha’s little white dual-sport.

For your daily dose of off-road goodness, make sure to fallow me – @TonyBlazier on Instagram and Twitter.