For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at Kawasaki’s first revision to their perimeter frame concept, the 1992 KX125.

For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel we are going to look back at Kawasaki’s first revision to their perimeter frame concept, the 1992 KX125.

|

|

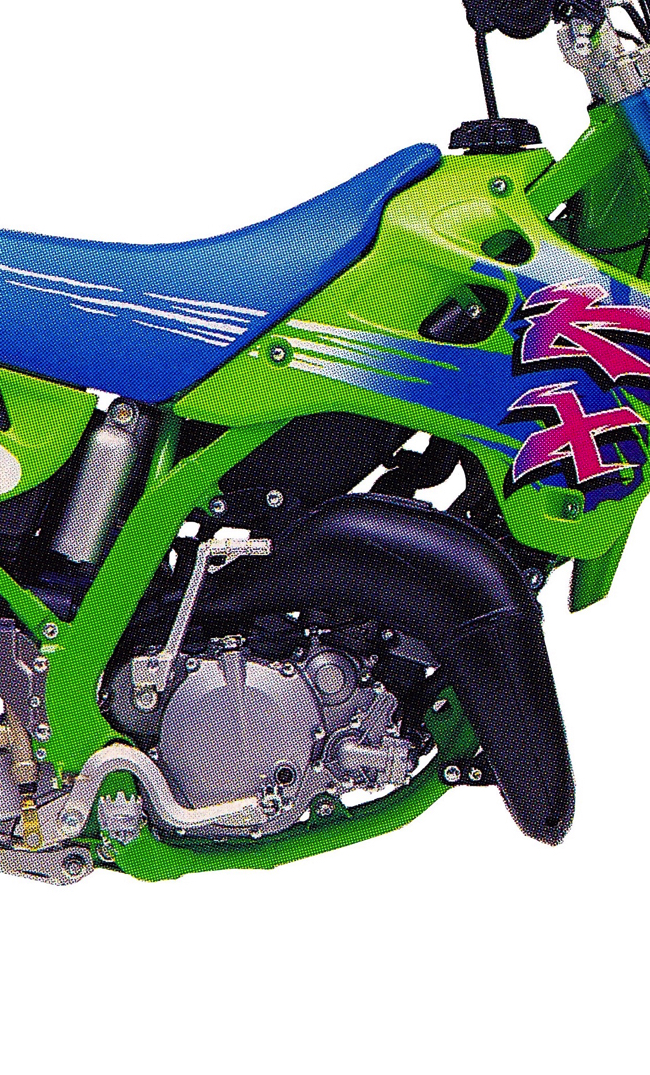

The 1992 KX125 was the first major renovation of Kawasaki’s innovative perimeter frame design. Originally introduced in 1990, the first generation chassis had been admirably stout, but overly large and bulky. For 1992, Kawasaki pinched, trimmed and reconfigured every part of the KX chassis in an attempt to scale down its husky proportions. While still the largest bike in the class, the new KX was slimmer, sleeker and far easier to move around on than previous models.

Swiz-“I gotta say, I owned this bike and I can remember when I first saw it, I couldn’t imagine a better looking MX bike could ever be realized. I still think it’s a stellar look. But oh did it’s looks outkick it’s capability-coverage… Yikes!” |

In 1990, the Kawasaki KX125 took a major leap from safe and stodgy to racy and radical. Overnight, the green machine went from the most conservative bike on the track to the most cutting edge. With a spacy design, snappy motor and outrageous styling, the all-new 1990 KX125 was the perfect bike for the nineties and buyers snapped them up in droves.

|

|

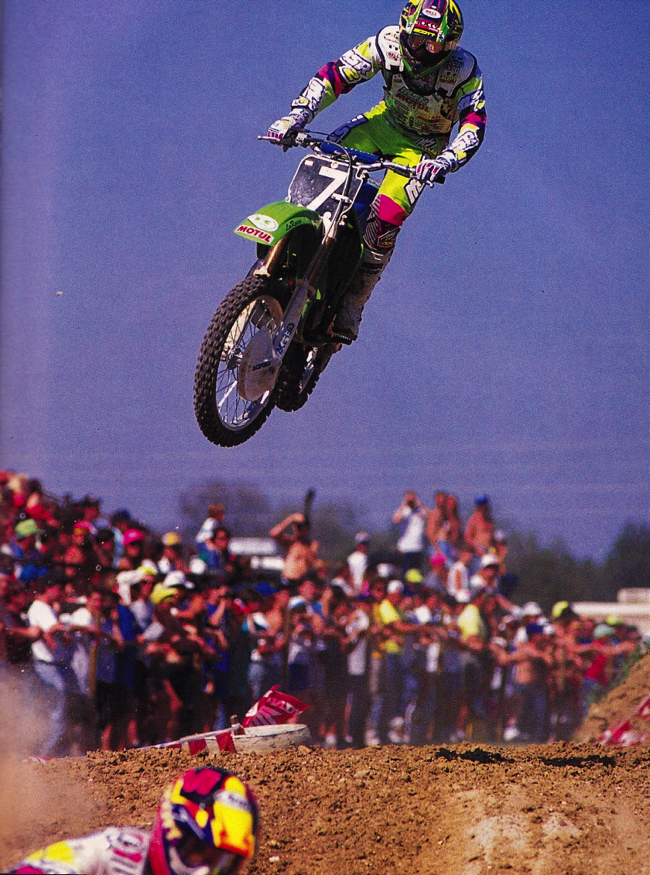

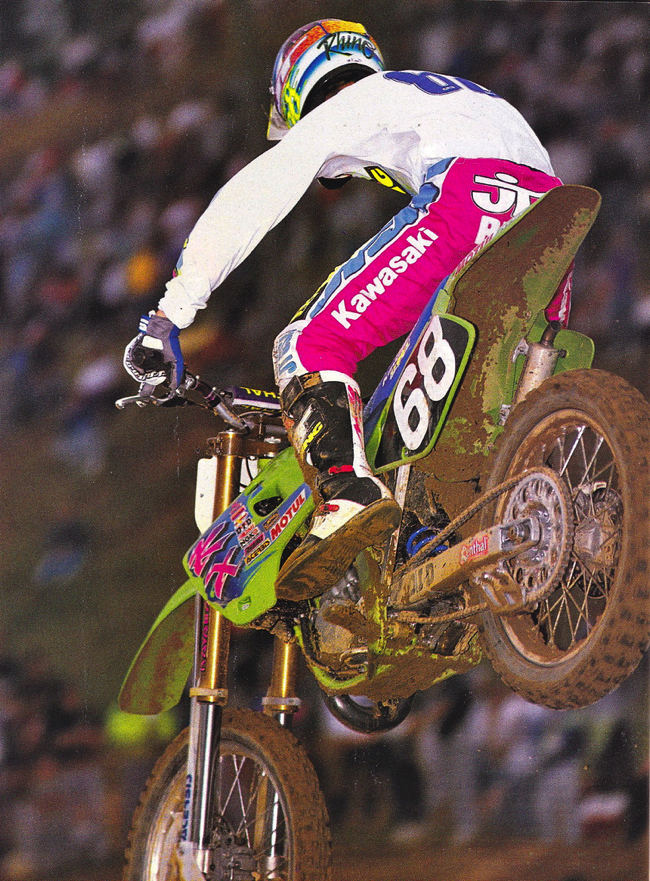

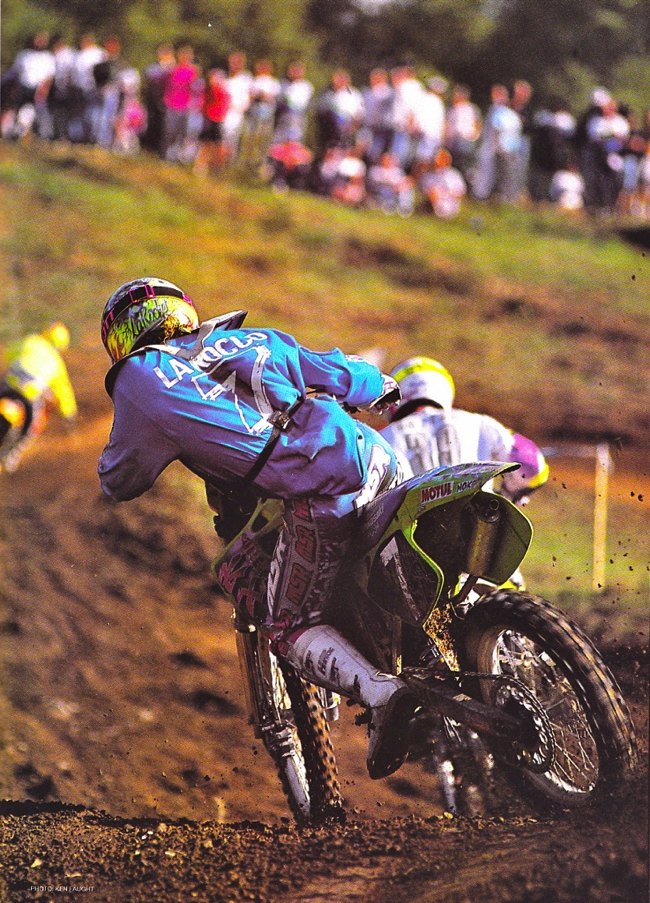

In the eighties and early nineties, it was quite common to have your top guys race the 250 class (then the premier division) indoors and then drop down to the 125’s outdoors. In 1992, Kawasaki’s latest hire Mike LaRocco opened the season by winning the first round in Orlando on his Factory Kawasaki KX250. Come March, Mike stepped down to the 125 class to battle the kids on his KX125. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider Magazine |

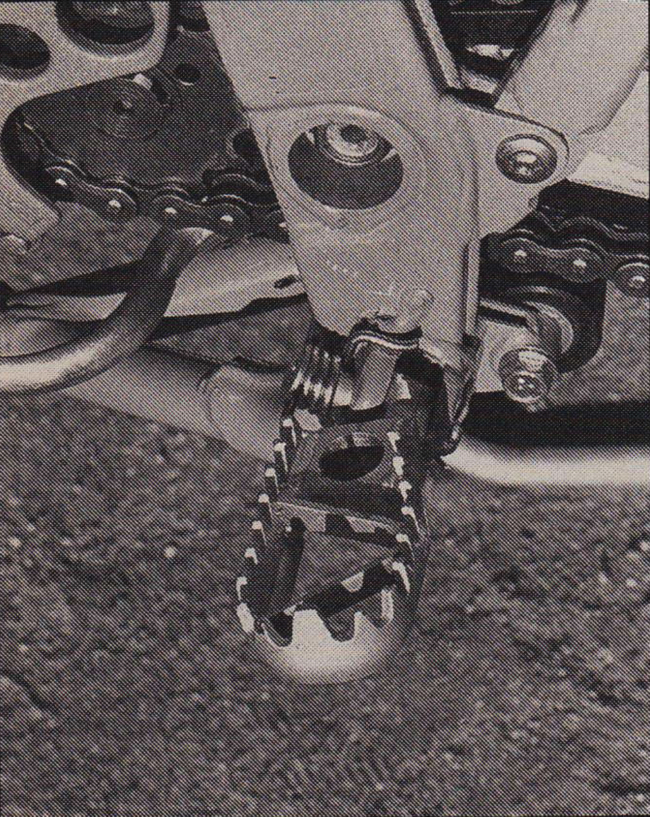

While immensely popular, the new 125 Kwacker was far from perfect and riders quickly found reasons to complain about its avant-guard design. The road-race inspired perimeter frame was cool to look at and incredibly strong, but it was also wide, heavy and tall. This made the bike feel like a 250 in a class full of cut and thrust tiddlers. The innovative bolt-on alloy shock tower mounts and giant platform pegs were trick, but prone to failures. The motor, while decently fast, was boggy off the line and reluctant to shift under power. The KX was still great to look at and fun to ride, but a little fine tuning would certainly have helped.

|

|

The new chassis on the ’92 KX featured narrower and slimmer frame spars that made the bike much less wide through the middle. In addition to the trimmer midsection, a new tank and radiators were spec’d that sat two inches lower on the chassis to improve weight distribution. This allow for easier rider movement fore and aft.

Swiz-“Yup, Kawasaki had the ergonomics nailed on this bike. It was so much more seemless to straddle than any other bike yet. The seat/tank junction was definitely studied by the other manufacturers after this release because to this day, this bike is still near the top of the class for ease of moving forward in the corners.” |

For 1992, Kawasaki planned to address these complaints with an all-new KX125. This was remarkably only two years after the complete 1990 redesign (contrast that to today, where a basic design can remain in use for a decade with only minor refinement). The ‘92 bike would be all-new from the ground up, with major revisions to the motor, suspension, frame and bodywork.

|

|

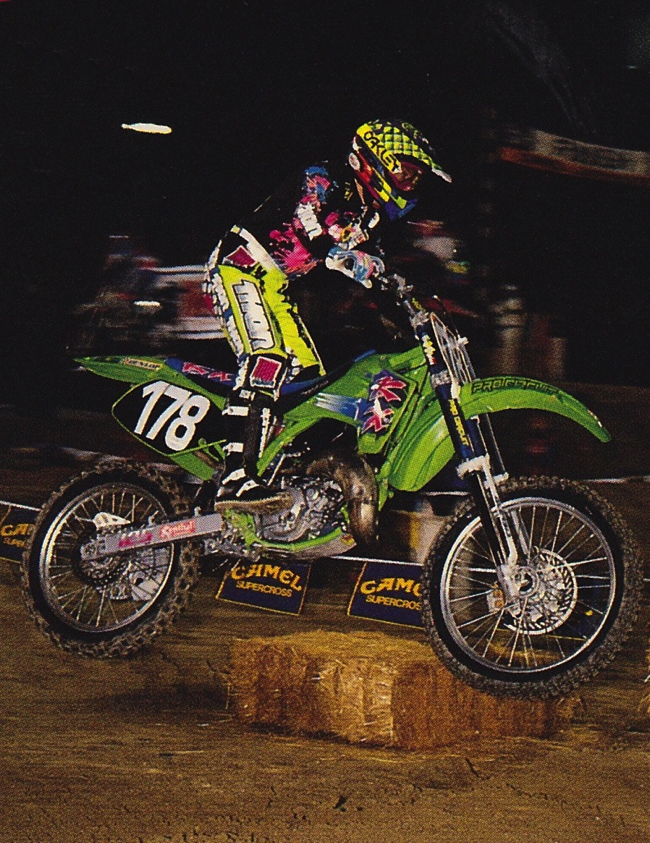

In the early nineties, the aftermarket motocross graphics movement exploded in popularity. Any number of companies offered ways to turn your KX blue, RM pink or your CR green (with outlandish graphics to match). One of the early pioneers in this arena was Illinois’ Tuf Racing, which became well known for campaigning orange Kawasaki’s with Keith “Bones” Bowen at the controls. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike magazine

|

The new frame took into account the criticism directed at the first gen design and aimed to trim both weight and sharpen handling. An all-new motor mimicked the dimensions of Honda’s class dominating CR125R and looked to broaden the KX’s punchy, but narrow powerband. All-new bodywork was lower, sleeker and more ergonomic, with a flatter seat and narrower midsection. Up front, the suspension remained largely unchanged (aside from minor valving changes), but an all-new Kayaba shock graced the back of the ’92 KX.

|

|

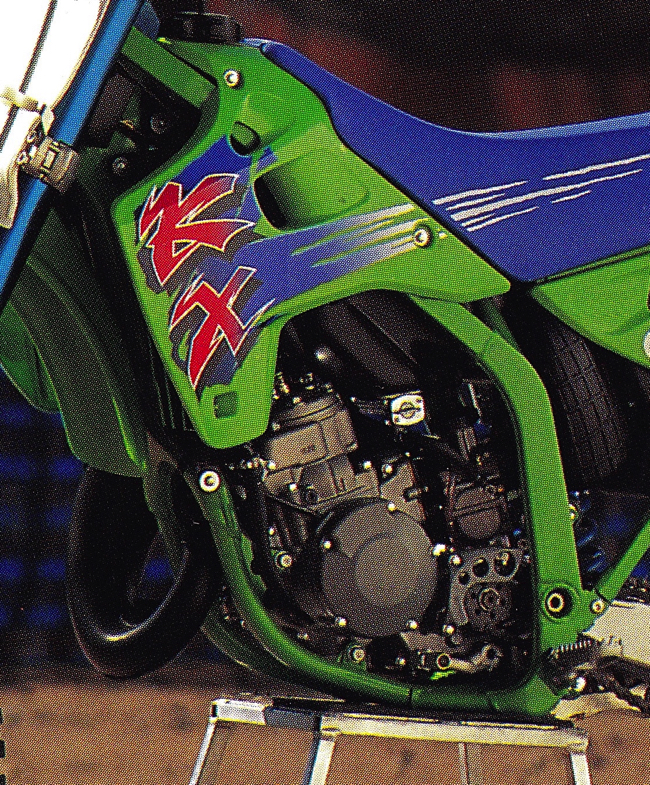

For 1992, Kawasaki spec’d an all-new motor for their eighth-liter racer. The new 124cc mill used a longer stroke and larger carb for ’92 to produce a wide and very useable powerband. Not as outright fast as the CR or lighting quick as the RM, the KX’s motor was broad and easy to use, but not particularly thrilling to ride.

Swiz-“”Not particularly thrilling to ride”… Wow can I back that up. I had an ’84 CR125 that would lay waste to the motor on my 92 KX125. I’m not real sure where Kawasaki went wrong with the engine on this bike but it was so far in the opposite direction of all the positives of this machine it was crazy. It looked amazing, had incredibly good suspension and stopped “well” but holy shit was this a short-shifting, lackluster engine…” |

With the new motor, Kawasaki looked to broaden the KX’s powerband by increasing the stroke 3.9mm and reducing the bore. This yielded a nearly square 54 x 54.5mm bore and stroke and a total of 124cc of displacement. In addition to the new motor configuration, Kawasaki spec’d a new flattop piston (with Nikasil-plated piston skirt), revised the KIPS (better sealing guillotine valves) and a dual-coil ignition (fatter spark). A new larger airbox flowed more air (and eliminated the adjustable vents on the side) and fed a 1mm larger Keihin PWK36 carburetor. Lastly, a revised pipe and silencer flowed more exhaust (and eliminated the KX’s notoriously tinny exhaust note) and larger radiators (shared with the KX250) kept the new power plant from boiling over.

|

|

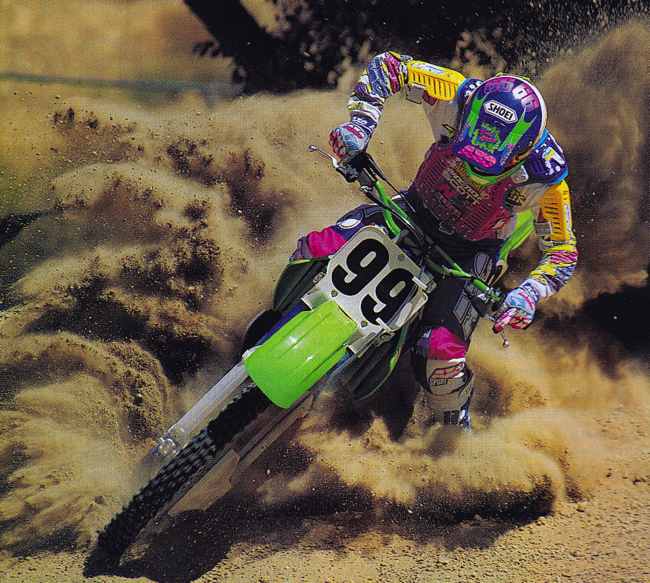

In 1992, one of the fast young graduates of Kawasaki’s Team Green program was Largo, Florida’s Tim Ferry. Timmy would spend the ’92 season on the new KX125, before moving to Yamaha for the 1993 season.

Swiz-“I have no doubt that the crappy motor on the 92 KX125 had Timmy looking for a different color early in the 92 season…I have no proof to back that claim up.” |

On the track, the new KX was improved, but not the best 125 motor on the track. Power was good off the bottom (far better than the boggy CR and anemic YZ), solid in the middle (not as hard hitting as the ultra-snappy RM, but on par with the CR) and decently fast on top (WAY better than the DOA Yamaha, on par with the Suzuki and a mile behind the eye-wateringly fast Honda). While not remarkably fast, it was exceedingly flexible and easy to ride. It was very similar to the Suzuki’s powerband, but lacked the RM’s ultra-quick response and immediate spool up. It had power in all three fazes of the power curve and while not as fast as the rev-happy CR (nothing was in ’92), it was far easier to ride than the high-strung Honda or narrowly powered Yamaha. It made an excellent novice to intermediate motor, but would need some major port massaging to please the pin-it-to-the-stops crowd.

|

|

LaRocco would make his debut on the KX125 at the outdoor season opener in Gainesville where he would roost his Factory Kawasaki to the first 125 overall victory of the season. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Swiz-“ONLY the Factory KX125 would be able to scale the steep launch out of the pit in 1992 as far as KX125’s go. It’s a known fact that all KX125’s that were not Factory tuned were left in the lake at the bottom of the pit because they couldn’t make it up the hill…… alledgedly.” |

As to the new chassis, it was indeed much slimmer and more compact than 1991. The new frame spars were smaller, more rounded and welded to a larger and stronger steering head. The steering head angle was new and offered a half-degree more rake than ‘91. The bolt-on alloy shock towers were round filed and replaced with traditional welded-on steel mountings. A new steel cross-member was added behind the frame to increase torsional rigidity and a stronger swingarm was spec’d to fight flex under heavy loads. The revised frame also made better use of space between the main spars and the new bike offered a three-inch lower tank that no longer protruded into the riding compartment. This, along with a taller and flatter seat made sliding fore and aft much easier for 1992.

|

|

Another one of the up-and-coming riders on the new KX125 in 1992 was Santee, California’s Tommy Clowers. Clowers would spend several years on the circuit pursuing his Supercross dream, before gaining much greater fame in the new sport of Freestyle Motocross. |

Even with its smoother ergonomics and more streamlined chassis, the KX125 remained the biggest feeling bike in the class by a wide margin. The new KX125 shared most of the frame and all the bodywork with the KX250 (the main frame cradle was the only significant difference) and this gave the bike a larger than typical feel. Interestingly, this did not necessarily translate into more rider room, as the KX’s tall pegs and low bars made for a somewhat cramped rider compartment. It was tall and long, while also being short and squatty; weird.

|

|

The 125 crop of 1992 offered a varied and potent selection of machines to fill your racing needs. The Kawasaki, Suzuki and Honda all had their proponents, with only the woefully underpowered Yamaha struggling to find supporters. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Swiz-“As much crap as I talk on the Kawi motor, I knew a guy with a 92 Yamaha and both before and after he had motor work done on it, it sounded like it had a rag stuffed in the airbox and he was trying to pull a Mack truck through a set of Supercross whoops. That 92 CR125 motor though… now THAT was an engine!” |

In terms of actual handling, the new KX was by far the most stable bike on the track. It was rock solid at speed and made child’s play of the rough straights that had Honda and Suzuki pilots calling for their mamas. It was excellent in high speed sweepers and never did anything unexpected or sudden. Where it lost ground to the competition was in the slow speed sections, where its tall feel and slack head angle gave it sluggish feel. In flat turns, there was an annoying push to the front and the bike preferred to bounce off of berms instead of dive bombing the inside. Sliding the forks up in the clamps 6mm helped slightly, but that push never fully went away. On a tight track, the Honda and Suzuki could carve circles around the KX, but once things opened up, the Kawasaki gained back the advantage.

|

|

By far the best part about the all-new KX was its excellent suspension. Plush, well controlled and perfectly set up, these 43mm Kayaba’s were the Jedi Masters of the fork wars in 1992.

Swiz-“Pretty sure Kawasaki coined the term “plush” in 92 and that describes the feel perfectly.” |

Helping the KX’s excellent high speed handling was by far the best suspension on the track in 1992. Up front, the KX used a set of blue anodized 43mm inverted Kayaba forks that offered 12.2” of travel and 16 adjustable settings for compression and rebound. They were ultra-plush and did a tremendous job of gobbling up track obstacles. Really fast guys needed an upgrade in spring rates to fight bottoming, but for the other 95% of pilots, the forks were nearly perfect.

|

|

In 1992, Mike LaRocco’s teammate on the new KX125 was a young hot shoe by the name of Ryan Hughes. While Ryno would show plenty of speed on the one-two-five, inconsistency and injuries would hold him back from showing his true potential on the Factory Kawasaki machines. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

Out back, the ’92 KX used an all-new KYB shock that offered more oil capacity, and a longer shock body to fight fading. This was bolted to an all-new Uni-Trak linkage that offered a more progressive curve for smoother operation. Like the front, this new shock was proclaimed nearly perfect and riders raved about its excellent control and plush performance. Big hits and small were absorbed with nary a whimper and the KX could be smashed into obstacles that would terrify riders on lesser machines. In 1992, nothing was as smooth, supple or satisfying as the suspension on the KX125.

|

|

A big and fairly slow handling bike, the new KX was far better at blasting around the outside than trying to cut underneath opponents. Derik Natvig demonstrates the new KX’s berm blasting potential for Dirt Rider magazine’s cameras.

Swiz-“There was definitely a grenade or something buried in this berm. No way could the ’92 KX125 move earth like that.” |

While most every change for 1992 yielded a substantial improvement in performance, one area that proved a misfire was the new braking system. On the new KX, Kawasaki chose to ditch their reasonably powerful, but grabby binders for an all new full-floating design. The new brake system replaced the 1991’s solidly mounted front rotor with a fully floating unit that allowed the rotor to move independently of the hub. The outer rotor was attached to the hub mount by a ring of grommets that were designed to allow the disc to better center in the caliper for superior braking feel and power. While this had proved effective on road race machines, the new Kawasaki system turned out to be a massive disappointment.

|

|

Dynaride: Like a 1972 Buick, the Kayaba shock on the KX125 swallowed bumps and floated down the track. In 1992, nothing was as plush, comfortable and well controlled as the KX‘s excellent Uni-Trak rear suspension.

Swiz-“Well there was that one time I had a seat-bounce go horribly wrong and that little silncer spicket took a nice chunk out of my right hamstring. Always gotta protect the corn-hole, Donnie.” |

Both power and feel were lackluster and the new brake provided a mushy feel that never quite went away no matter how many times you tried to bleed the system. Braking power was so diminished that the KX finished behind even the notoriously wooden feeling KTM in the final brake rankings. The hot setup turned out to be ditching the new floating rotor completely and mounting on a solid unit. This combined with Motul 300c fluid and constant bleedings at least brought it back to 1991 levels. It was never going to out brake a Honda, but at least it was no longer in danger of being shown up by a 1981 Yamaha YZ465.

|

|

Marshmallow: One area that did not improve on the new KX was its brakes. The switch to a full-floating rotor for ’92 gave the front binder a vague and mushy feel that no one liked. Constant bleeding was necessary to maintain its meager performance and many riders reverted back to a solidly mounted rotor in search of better performance. #Fail

Swiz-“Yup this was another area the ’84 CR125 had this bike beat. THis implementation of floating disc and caliper definitely made for an inconsistent and spongy front brake. No good.”

|

As to the rest of the bike it was typical Kawasaki for the era. That meant the bolts, nuts and assorted screws were generally of the same grade as a typical Budweiser can. They stripped, deformed and generally fell off at regular intervals. Careful care had to be taken to assure the survival of the subframe riv-nuts, seat bolts and side panel mounts. Footpeg springs jumped ship like lemmings off a cliff and linkage bolts were infamous for backing out, with predictably dire consequences. Maybe the most annoying, however, was the KX’s gas cap, which continued to be a Kawasaki bugaboo. If you cinched it down too tight it cracked or deformed the seal, if you tried to be gentle, then it leaked gas in your lap. Nothing cuts a moto short like your balls on fire let me tell you.

|

|

Jumbo pegs were a Kawasaki exclusive in 1992.

Swiz-“Ha!, “Jumbo”. Yes, these really were jumbo in 1992.” |

|

|

Coming into the penultimate round of the 1992 125 National championship, Team Kawasaki’s Mike LaRocco held a commanding 48 point lead over Team Yamaha’s Jeff Emig. At Steel City, however, the wheels would come off the LaRocco bandwagon. Back-to-back DNF’s in both motos (a blown tranny in moto one and an ejecting carburetor in moto two) would cut that massive points lead down to a single point heading into the series finale at Budds Creek. At Budds, Mike’s horrible luck would continue with a broken shifter in moto one, leaving the door open for Jeff Emig to roost away to his first ever National Motocross title |

Aside from these minor quibbles, the new KX125 was an excellent racing motorcycle. It offered a broad powerband that was easy to use and the best suspension on the track by a wide margin. It was not as fast as the Honda or as snappy as the Suzuki, but it had more than enough power to get the job done for anyone below the pro class. It’s big feel put off some, but it was stable and confidence inspiring in situations that were terrifying on its competitors. High speeds and rough terrain was its wheelhouse and the little KX allowed riders to charge without fear of a sudden swap or unpredicted course correction. For pros, the Honda or Suzuki were probably a better choice, but for the majority of 125 riders, it was hard to go wrong with Kawasaki’s little one-two-five.

|

|

In 1992, the Kawasaki KX125 offered clean looks, a broad powerband and the best suspension in the class (by a wide margin). It was no scalpel in the turns, but it was easy to ride and a great overall machine.

Swiz-“Mine was extremely easy to ride but worked better as a mosquito-sprayer with all the smoke it constantly bellowed. Oh yeah, the one failing of this bike in terms of looks, it still had that ugly super wide front fender. If you’re a dope and still ride one of these today, at least throw a ’93 Kawi front fender on it.” |

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier