For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the first of the fluorescent Hondas, the 1992 CR250R.

For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the first of the fluorescent Hondas, the 1992 CR250R.

|

|

|

|

|

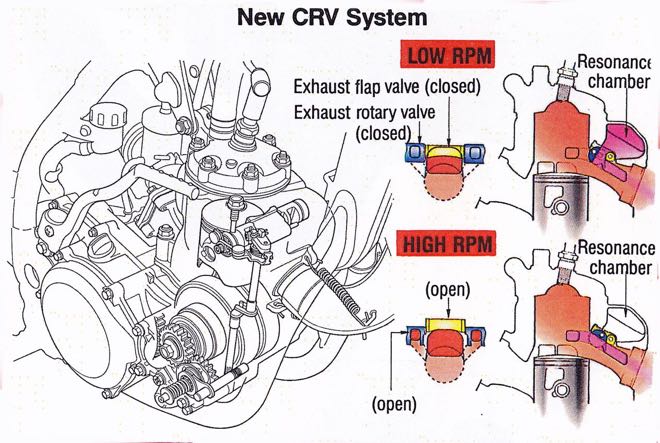

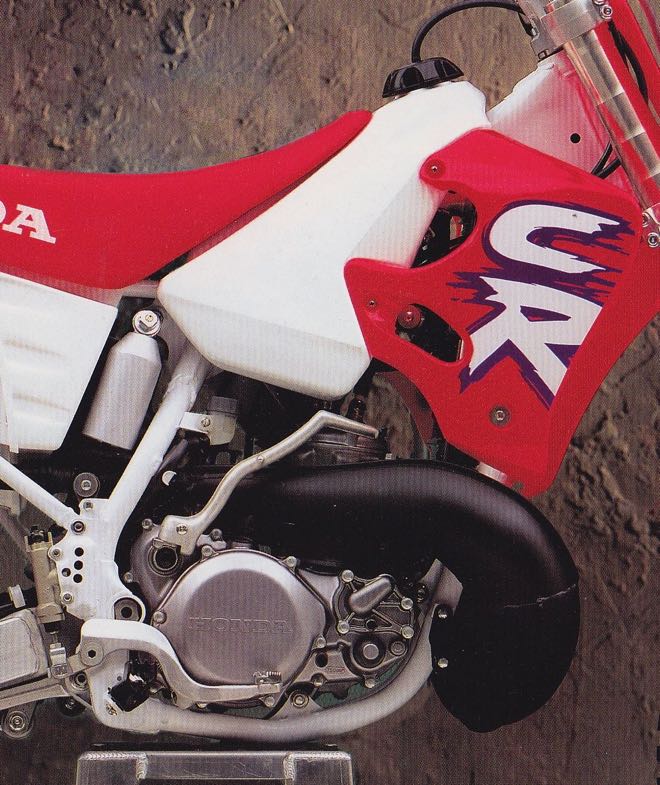

In 1992, Honda introduced its first all-new power valve system since the introduction of the Honda Power Port (HPP) in 1986. Coined the Composite Racing Valve (CRV), the new design utilized a rotary valve (like a Yamaha YPVS), sub ports (like a Kawasaki KIPS) and an exhaust resonance chamber (like Honda’s own ATAC) to provide an incredibly potent power package. Photo Credit: Honda |

The linchpin of this unprecedented run of motocross titles was the CR’s amazing motor. Originally introduced in 1986, the Honda Power Port (HPP) mill was a marvel of smooth and broad power. Using a complex set of gears, springs and valves to alter port timing, the HPP motor pulled longer and stronger than any other bike on the track and made the CR the powerhouse of the late eighties and early nineties.

|

|

The new frame on the CR250R was both lighter and more compact for 1992. Wheelbase was trimmed a full inch and overall width was down 18mm over ’91. In addition to the tighter dimensions, new clamps and a revised steering head decreased rake by 2 degrees for sharper turning. Photo Credit: Honda |

By 1991, that remarkable motor was coming up on its sixth year at the front of the pack. It was still the fastest motor in the class, but many riders had come to loath its tedious maintenance schedule. The HPP system, while proficient at producing power, was prone to carbon buildup and a nightmare to service. The mechanism required disassembly after every few hours of use and neglect meant a major drop in performance. It was wearisome to take apart, difficult to reassemble, and easy to screw up.

|

|

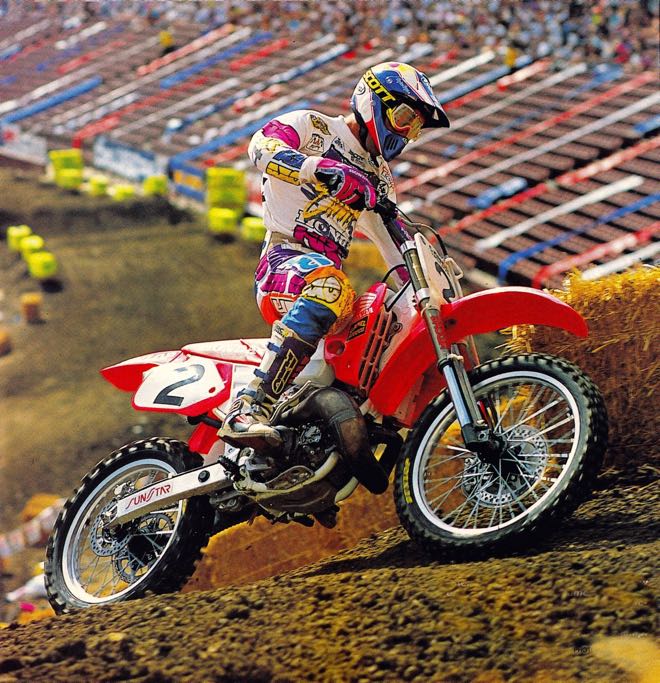

At Anaheim in 1991, Honda gave everyone a preview of things to come by decking out Jeff Stanton’s (pictured) and Jean-Michel Bayle’s factory bikes in neon red plastic. At the time, Honda stated the reason for the change was to provide better visibility for their machines on TV. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike magazine |

Also becoming tiresome was Honda’s utter failure to provide this rocket with even mediocre suspension performance. Since the glory years of 1986-1987, the CRs had become less and less efficient at absorbing the track. Year in and year out, the CR250R came with harsh and poorly set up suspension. The switch to inverted forks in 1989 only exacerbated this problem and by 1991, the CR had earned a reputation for being as punishing on your backside as it was fast.

|

|

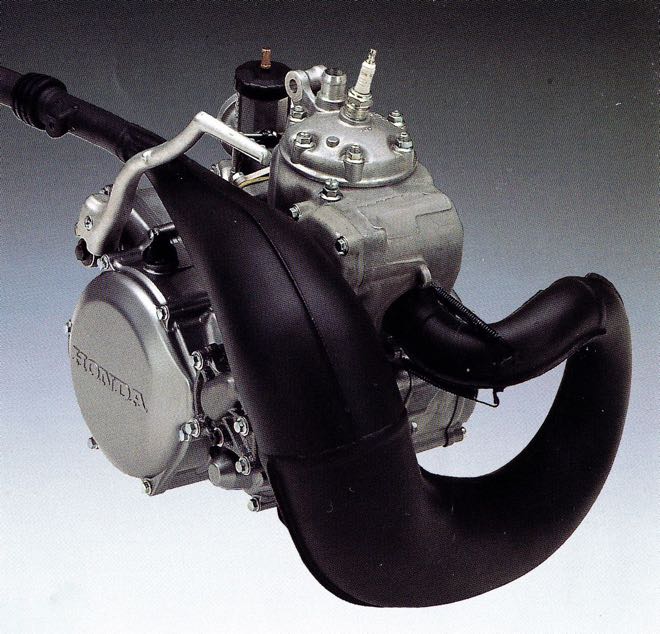

The CR’s new 249cc two-stroke motor was both lighter and more compact than the popular HPP mill it replaced. The CRV system used 50% less parts than the old design and helped shave a full two pounds off the motor’s weight. In addition to saving weight, the new CRV system addressed the main complaint with the old design by being far less labor intensive to service. Photo Credit: Honda |

For 1992, Honda looked to address all these issues with an all-new CR250R. The new bike retired the championship winning 249cc mill used since 1986 and replaced it with an all-new design that was both lighter and more compact than the old motor. The new power plant retained the cylinder-reed intake of the old mill, but replaced the HPP with an all-new exhaust valve that used 50% less moving parts. The new Composite Racing Valve (CRV) did away with the guillotine valves of the HPP and replaced them with a new dual-valve design that incorporated both the variable port timing of the HPP and the resonance chamber of Honda’s old ATAC system. Similar in theory to Kawasaki’s KIPS, the new CRV was lighter, less complicated, and easier to service than the old HPP system.

|

|

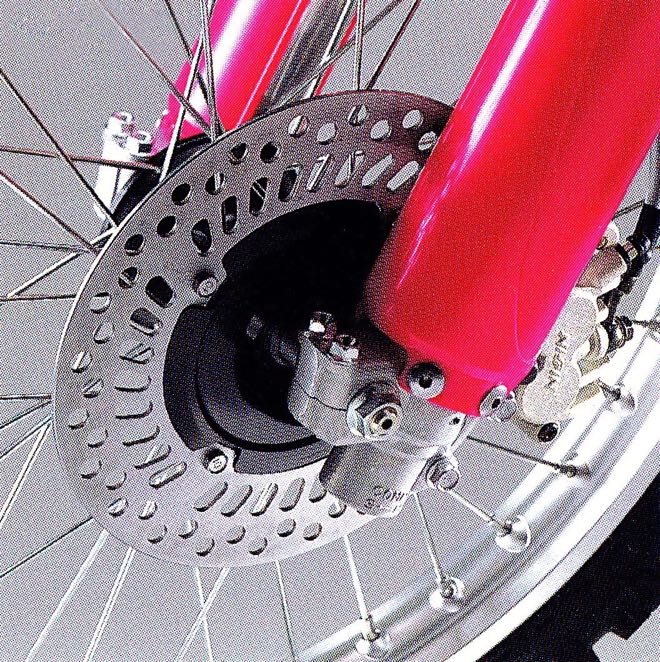

New lighter wheels shaved off precious ounces of unsprung weight and a new front caliper offered increased volume for better fade resistance. Photo Credit: Honda |

In addition to the revised power plant, Honda spec’d an all-new chassis that was narrower, lighter and more compact for ’92. Overall wheelbase was shorter by a full inch and the steering head angle was steepened 2 degrees for tighter turning. Complementing the new frame was radically changed bodywork that offered a smoother rider compartment, narrower profile and bold new look. The new plastic ditched the orange-mist of 1991 in favor of a neon shade Honda coined “Nuclear Red”. Bright and eye-popping, the new color was like nothing ever seen on a Honda motocross machine.

|

|

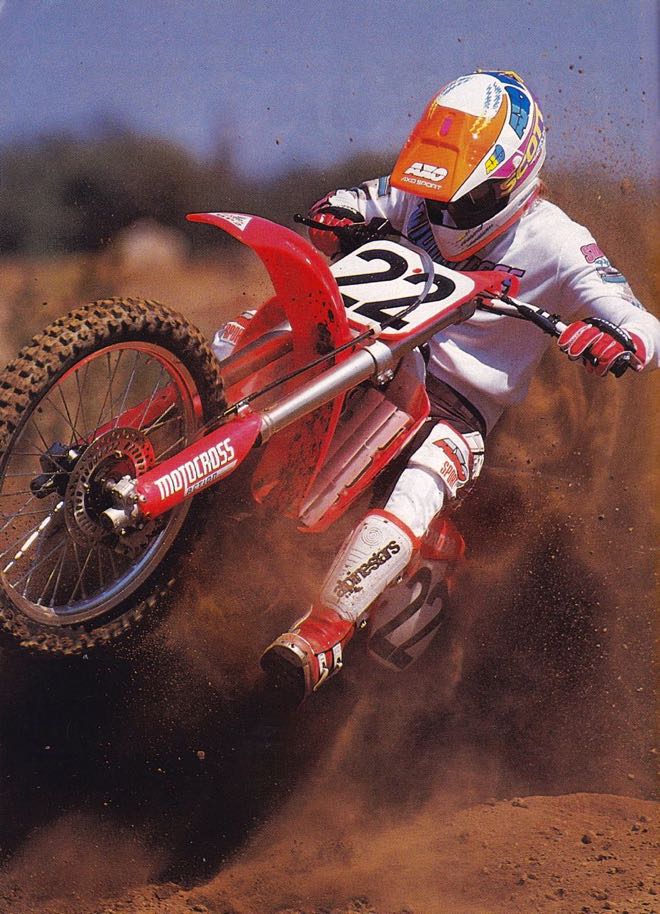

In 1992, no berm was too deep for the mighty CR250R. What previous red machines did with an electric flow of ponies, the new CR accomplished with a hard-hitting blast. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

Complementing the new frame was a redesigned Pro-Link rear suspension and a new set of 43mm Showa inverted forks. Pared down 2mm for ’92, the new smaller forks aimed to dial back some of the harshness from Honda’s ultra-rigid front end. Finally, finishing off the package was a set of new lighter wheels and a redesigned front braking system. Already the standard of the class, the new Nissin binder offered more power, better feel and a shorty lever to afford more rider comfort.

|

|

While the new bike was a notable improvement in most areas, there were still a few issues to be ironed out. Early on in the Supercross season, both Jean-Michel Bayle and Jeff Stanton struggled with the handling of their bikes. Eventually, the problem was traced to the new frame, which was underbuilt and prone to severe flexing under heavy loads. By midway through the season, Honda had sorted the problem and both JMB and Stanton were back at the front. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider |

On the track, the new bike ran absolutely nothing like the bike it replaced. Where the ’91 motor was smooth and torquey, the new CRV mill hit hard and revved fast. What the old motor did with a seamless crescendo of power, the new bike accomplished with a sudden bark and a furious pull. It was slightly soft off idle, before catching fire in the midrange and pulling to an eye-watering top-end hook. On slick surfaces, it was harder to get hooked up than the old bike, but if there was traction, the new machine roosted away. It was snappy, snarly and by far the fastest motor in the 250 class for 1992.

|

|

By far the biggest star of the 1992 AMA Supercross season was Yamaha’s Damon Bradshaw. Early on as Team Honda struggled, Damon rattled off win after win. In all, Bradshaw would total nine wins to only three for the eventual champ. In the end, however, Stanton’s superior consistency (and lack of boneheaded moves) would win the day over Damon’s raw speed. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer/Dirt Rider |

|

|

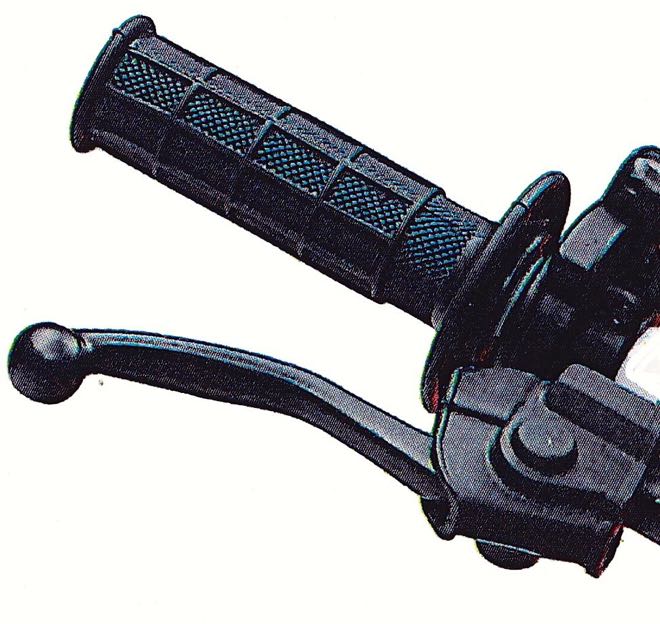

Complementing the new front caliper was an all-new master cylinder that offered more power, better feel and a new shorty lever that allowed for an adjustable reach for the first time. Photo Credit: Honda |

While the new motor’s prowess was a welcome relief to those who lamented the passing of the HPP mill, the real question for 1992 was whether the new bike would finally fix the CR’s suspension problems. The new 43mm Showa sliders offered 4mm more travel for ‘92 and a new cartridge system brought rebound adjustability for the first time. Internally, a new alumite coating reduced friction and a revised oil lock system aimed to reduce aeration of the oil. With 14 compression settings and 17 available rebound adjustments, the new forks were by far the most adjustable units ever offered on a CR.

|

|

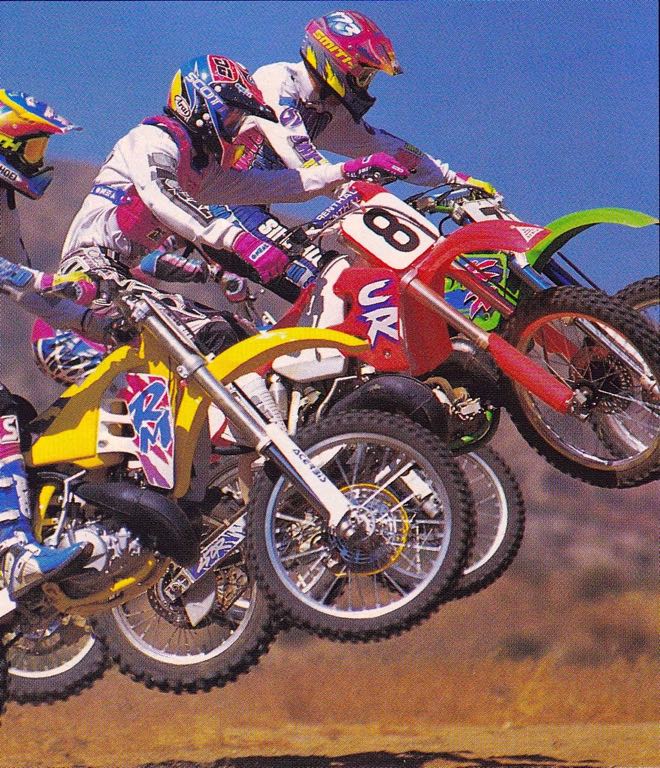

Pete Murray, Troy Welty and Mike Young putting the 1992 Suzuki RM250, Honda CR250R and Kawasaki KX250 through their paces in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

In terms of performance, the new forks were an improvement, but still far from good. There was slightly less of the mid-stroke harshness that battered rider’s wrists in 1991 and a little more flex in the new triple-tapered legs, but performance still lagged well behind the competition. As delivered from the factory, they were under-sprung and over-damped. This caused them to hang down in the stroke and blow through the early part of the travel. On big hits, they hammered into a wall of damping mid-stroke and would absolutely refuse to bottom. If you upped the spring rate and lowered the oil level, action improved significantly and the fork would actually move all the way through its travel. By no means was it plush, but at least these simple mods could make it livable.

|

|

Since the switch to inverted forks in 1989, Honda’s front suspension had consistently offered the worst ride in motocross. Poorly set up, harsh and unforgiving, they transmitted every rock and ripple directly to the rider’s wrists. For 1992, Honda tried to address some of these concerns by downsizing the diameter of the forks 2mm, redesigning the cartridge system, and adding a rebound adjustment for the first time. While overall performance was improved, the new Showa units were still set up poorly and harsh in action. Too soft initially, then absurdly stiff at the bottom of the travel, they continued Honda’s run of disappointing front ends. Photo Credit: Honda |

|

|

Au Revoir: The reigning AMA Supercross, 250 and 500 National Motocross champion, Jean-Michel Bayle came into 1992 with all of his goals achieved. In Supercross, he put up a good fight (until a crash at San Jose dashed his title hopes), but in the outdoors, he seemed more interested in messing with his Honda teammate than backing up his 1991 titles. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata |

Out back, Honda decided to return to a Showa damper on the CR250R after using a KYB unit in 1991. The new shock offered a larger 46mm shaft, longer stroke and more internal volume than before. Punching out 12.6 inches of travel, the new unit offered 20 adjustable compression and 22 rebound settings. Mated to the new shock was a redesigned Pro-Link linkage and a new shorter and stiffer alloy swingarm.

|

|

An all-new Pro-Link suspension graced the rear of the 1992 CR250R. Much like the forks, it was good at taking big hits, but less adept at chop and chatter. Braking bumps and sharp edges caused the rear to kick and most riders found it only marginally better than the unloved 1991 version had been. Photo Credit: Honda |

|

|

When new, Honda’s Nuclear Red plastic was certainly eye catching, but it did not wear nearly as well as previous shades had. The new color tended to fade very quickly when subjected to the sun and the new thinner bodywork showed ugly white creases when bent. Photo Credit: Jeff Ames |

While the rear suspension was all-new, its performance was not. On the track, it reacted more or less the same as the loathed 1991 rear end. If ridden aggressively, it absorbed big hits well, but if you dialed down the pace, it literally beat you to death. On small chop and sharp hits, it kicked and was very unforgiving. Under acceleration, small bumps were transmitted directly to your spine, and under braking the bike became very unstable. The new chassis proved very adept at corners, but at speed, it was a handful. The short wheelbase, quick steering geometry and unsettled suspension made hitting fifth gear on a long straight a harrowing experience. The bike never felt planted and once you commenced to slowing down, it developed a nasty swap and vicious headshake.

|

|

Saturn Missile: Where the HPP motor was electric and smooth, the new CRV version was hard-hitting and abrupt. There was less low-end power than ’91, but far more midrange and a tire-shredding top-end hook. Once on the pipe, the Red Rocket pulled farther and harder than any other bike on the track. Photo Credit: Honda |

On the plus side, once on a supercross-style circuit the bike was much happier. The stiff suspension, hard-hitting motor and cut-and-thrust chassis worked well in this environment. The CR offered a very light feel in the air and on the ground that made tricky jump combos a piece of cake. The new front brake was also a major improvement, with excellent feel and class-leading power. In 1992, nothing accelerated, turned, or stopped as well as the CR.

|

|

The 1992 crop of 250s was certainly a colorful lot. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

Unfortunately, the suspension performance turned out to not be the only downer with Honda’s newest baby. While the new bodywork was lauded for its fit, feel and overall look, the new thinner plastic proved less durable than in the past. The fluorescent color quickly faded from red to pink and even the slightest bend left an ugly white crease. There were also issues with broken clutch plates and baskets, as well as durability problems with the frame. With hard use, both the frame and swingarm developed cracks and savvy riders started adding material to shore up the overtaxed chassis. Overall, it was well put together, but a definite step down from Honda’s unusual levels of quality.

|

|

In 1992, Honda introduced the fastest, quickest-handling and boldest-looking CR yet. Blazing fast, but poorly suspended, it was a bike with a ton of potential, but in need of a little polish. Photo Credit: Honda |

In 1992, Honda released the ultimate supercross weapon. Razor sharp, rocket fast and relentlessly demanding, it was a bike made to dominate in the stadiums. There were smoother motors available, plusher forks on the market and more-stable chassis on the track, but nothing as laser-focused as Honda’s new neon CR. If you were fast enough to make its suspension work and strong enough to use all of its potential, nothing else in 1992 was even close.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com