For this edition of GP’s Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the last of Yamaha’s big-bore two-stroke YZs, the 1990 YZ490.

|

| After languishing in Yamaha’s lineup (and in showrooms) for half a decade with only minor updates, Yamaha finally put the mighty YZ490 out to pasture in 1990. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

Today, the Open class is once again King. Long the most-storied division in motocross, the Open class fell on hard times in the early nineties, only to rise again like a phoenix on the back of a four-stroke revolution. Once the very definition of manly machismo, the Open bike fell prey to budget cuts, manufacturer neglect, and the fickle tastes of the buying public.

|

| Carving arcs in deep loam and sand are what Open bikes do best. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

Today, however, the Open bike is back. The new generation of four-strokes, with their fuel injection, fancy electronics, and easy-to-manage powerbands have made “Big” beautiful again. In 1981, a 450cc motocross bike was a terrifying machine with a light-switch power curve and an appetite for destruction. Today, a 450 machine is a gentle giant, with a power curve as mild, or wild, as you desire. Turn it on a little, and it goes a little. Turn it on a lot, and the scenery starts to blur big time, but at no point does it try to spear you into the track like a 200-pound lawn dart. Today’s Open bikes are still big and brawny, but no longer brutish.

|

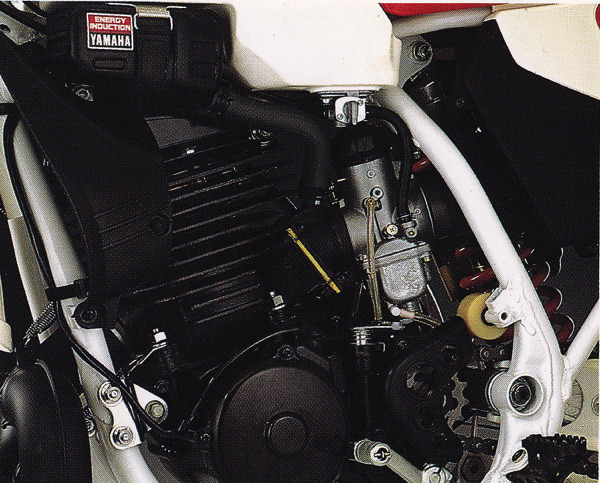

| Largely unchanged since its introduction in 1982, the YZ490’s 487cc mill was the model of industrial simplicity. Devoid of water cooling, resonance chambers or exhaust doohickeys, the 490’s only nod to modern two-stroke design was a reed-valve for the intake. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

The decline of the Open class started in the early eighties, with the rise of better and better 250s and 125s. As the small bikes got better, interest in the big bores began to wane. To bolster sales, the manufactures turned to that old American trick of boring out the cylinders and before you knew it, the manageable YZ360 had become the arm-stretching and eyeball-watering YZ465. In America, bigger is always better, and the manufacturers were happy to oblige.

|

| In 1982, Yamaha retired the legendary YZ465 and introduced the world to its successor, the YZ490. Portly, ponderous and ill-handling, the original YZ490 was not nearly the follow-up the Yamaha faithful were hoping for. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

Unfortunately for big bike enthusiasts, however, this “bigger is better” strategy turned out to backfire. As the bikes became more powerful (and more unruly), the mass exodus away from the Open class got even worse. As sales tanked, so did the manufacturer’s interest in development and Open class innovation went from the fast track to the slow lane.

|

| Early YZ490s were not the best-handling bikes on the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

The first casualty of this Open class retreat was Suzuki, who pulled the plug on their RM500 in 1984 (it continued in 1985 in some other markets, but not in the US). This left Yamaha, Honda and Kawasaki as the only Japanese manufacturers still producing a 500-class machine. In 1985, both Honda and Kawasaki added liquid cooling to their big bores, but Yamaha chose to keep it simple and stick with air for their cooling needs. In 1986, Kawasaki added a Power Valve to the mighty KX500, but Yamaha once again choose to stand pat and eschew the fancy-fangled do-dads. Claiming that Open class riders neither needed nor desired these features, they continued to offer an engine package that favored simplicity over innovation.

|

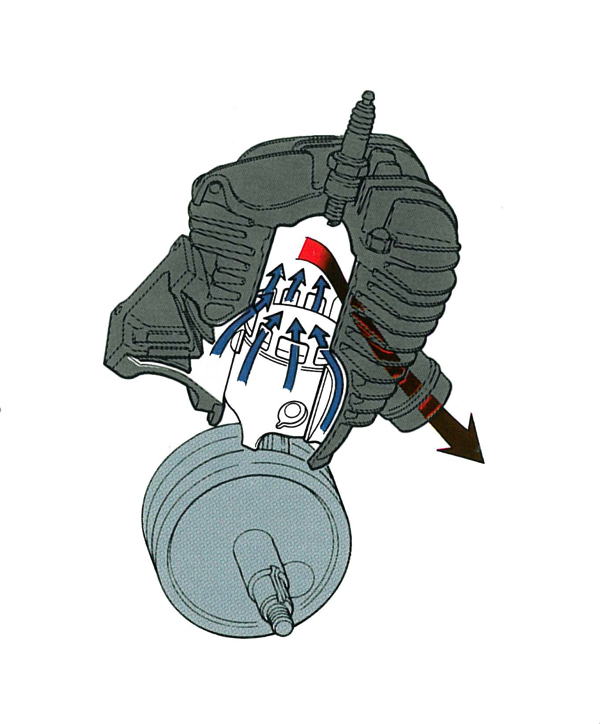

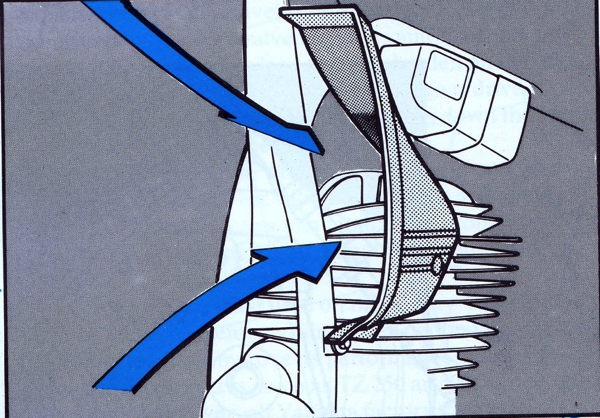

| Energy Induction: Remember the Boost Bottle? Chances are, if you are not racing in the 40+ class, you probably don’t. All the rage in the late seventies, the Boost Bottle consisted of a small hollow canister that was connected to the intake manifold via a rubber hose. The theory behind this gizmo was to provide the motor with a small air reserve that would smooth out fluctuations in intake pressure, and in turn, improve throttle response and low-end torque. In 1981, Yamaha became the first manufacturer to actually stick one on a production bike, renaming it “Energy Induction” and bolting it on the YZ250. Quickly forgotten by the rest of the motocross world, the Boost Bottle would live on in Yamaha’s lineup on the YZ490 until the model’s demise in 1990. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

| By 1990, the YZ490’s days as a top-flight motocrosser may have been in its rear-view mirror, but it still made an excellent off-road play bike. Credit: Dirt Bike |

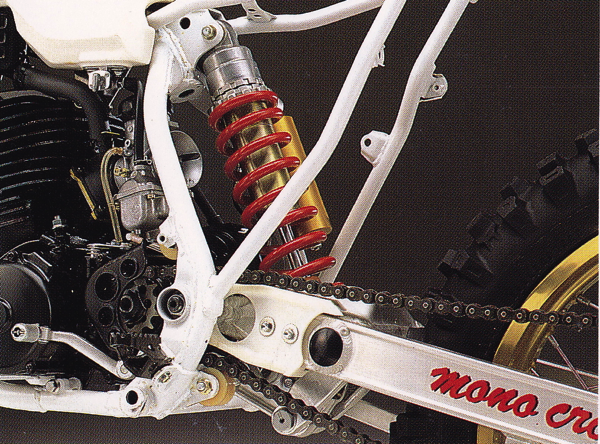

While Yamaha did not see fit to spec an all-new engine for 1986, they did dial up a major redesign for the rest of the machine. A new frame lowered the center of gravity by repositioning the Monocross linkage below the swingarm for the first time and all-new bodywork slimmed the midsection of the notoriously pudgy machine. While the basic motor remained largely unchanged, Yamaha did see fit to finally install a fifth gear into the big 490 to make off-roaders happy.

|

| Carl: In 1985, Broc Glover completed one of the most heroic feats in motocross history by taking a lightly-modified stock YZ490 to the 500 National Motocross title over David Bailey and his full-factory RC500. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

On the track, the new YZ490 offered improved handling and slimmer ergonomics, but not much of an upgrade in motor performance. The new fifth gear aided versatility, but the 487cc mill continued to vibrate and rattle like someone left a nut loose in the bottom end. Jetting on the 40mm Mikuni carb was hopelessly off and the bike blubbered down low and pinged on top. Unfortunately, swapping brass was not enough to alleviate this problem and getting it to run cleanly was virtually impossible without having the head modified. Overall power was decent, but not all that remarkable for a bike with a piston the size of a wash bucket. It was weak off the bottom (for a 500) and did not really get going until well into the midrange. The majority of its power was found on the top end, where most Open bikes feared to tread. Once on the pipe, it had plenty of power for most mortals and it could holeshot under the right conditions. Although the new fifth gear allowed the bike to perform better away from the race track, the action of the cogbox continued to be the worst in the class. Shifting was notchy at all times, but this was less of an issue on a big bike like the 490 than it was on the smaller YZs. In most cases, you just put the bike in third and left it there, until the vibration forced you to back off or you ran out of track.

|

| In 1986, Yamaha dialed up what would be the last of the YZ490’s major redesigns. Slimmer and better handling, the new bike was improved, but still behind the class leaders in technology. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

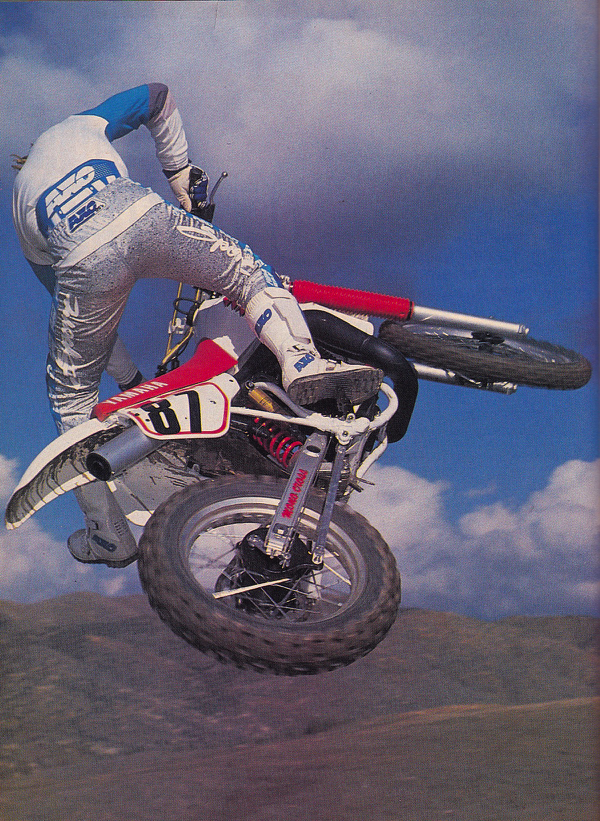

| Although not a natural flier, the YZ490 could be bent to the rider’s will by a talented pilot. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

In 1987, Yamaha tried to address the YZ490’s jetting woes by massaging the head and re-porting the air-hammer’s massive cylinder. They also attempted to upgrade the YZ’s mediocre fork action by bolting on a set of Kayaba’s new 43mm “Variable Damping” TCV (Travel Control Valve) forks. Neither of these “upgrades” proved particularly effective and the big Y-Zed continued to ping incessantly and pummel rider’s wrists.

|

| Clackity, clack: In 1990, the YZ490 was the only bike in the class without a detachable rear subframe. On the bright side, its absurdly hard and NOISY chain buffer was likely to last well into the next ice age. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

| Too Hip and the farm boy: In 1987, Team Yamaha’s Jeff Stanton took a lightly modified YZ490 to second behind Honda’s Rick Johnson in the 500 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Super Motocross |

|

| The big one-two-five: The motor on the YZ490 offered an unorthodox Open class powerband. Low-end power was soft, with the bike doing its best work from the mid-on-up. Top-end power was particularly strong, but the bike’s absurdly bad vibration made wringing it out a hand and mind-numbing experience. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

| Ramming speed: Detonation was a major issue on all the YZ490s and the problem never went completely away without having the head modified. Without the benefit of liquid cooling, Yamaha resorted to a ram-scoop on the left side of the frame to try and keep the big single’s temps under control. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

For 1988, Yamaha dialed up one last major update for the YZ490 by bolting on a set of Kayaba’s new 43mm cartridge forks. The addition of these works-style sliders finally brought the big Yammer’s suspension performance out of the dark ages and up to speed with its classmates. Aside from the new forks, the rest of the bike was basically a carryover from 1987. There was no fancy new disc brake for the rear, or sano liquid cooling to drool over. Just a simple bike with a really big piston.

|

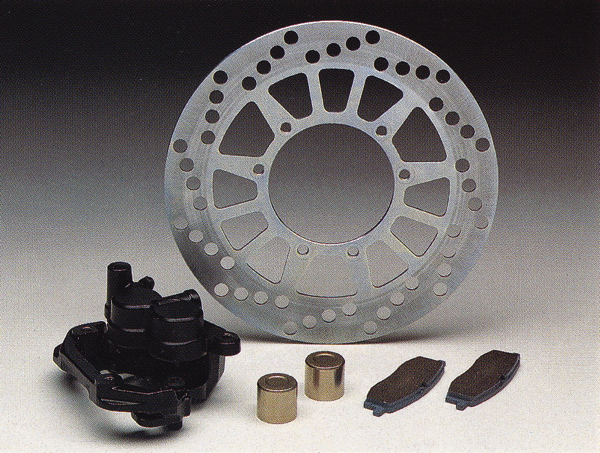

| In 1988, Yamaha boosted the stopping power on the YZ490 by upping the front disc diameter size from 220mm to 230mm. While competitive, the new stopper was still not as strong and trouble-free as the dual-piston Nissin unit found on the CR500R. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

On the bright side, the YZ continued to offer the easiest starting in the class (no small advantage on bikes like this), very good high-speed stability (no headshake, but a busy shock) and stone axe simplicity. With no radiators to smash and no power valves to futz with, the 490 was a weekend warrior’s dream. It could be fixed with a hammer and a screw driver and once the head was dialed, it actually ran pretty well. It also cost less than the competition, but not really enough to justify its lack of features.

|

| By far the biggest problem with the YZ490 was its cantankerous jetting. In stock form, it blubbered off the bottom and detonated on top. Unfortunately, no amount of brass-swapping in the 40mm Mikuni round-slide carb was enough to alleviate this chronic condition. The only true fix was to send out the head for modification and run race gas. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

| In 1988, Yamaha upgraded the YZ490’s forks to cartridge internals and brought their performance from grim to great. By 1990, the world was moving on to inverted designs, but the YZ’s 43mm conventional units remained competitive by being plusher than most of its upside-down rivals. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

| With a little fine tuning, the YZ490 was capable of running with any bike in the Open class. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

For 1989, the only thing YZ490 aficionados received was a whopping $500 price increase. This was due to a fall in the value of the Japanese Yen, but it still hurt on a bike that was essentially a warmed-over ’86. You did get Bold New Graphics and some minor frame tweaks, but overall it was the same do-it all machine it had been the year before.

|

| Yama-hopper: While the forks on the YZ490 were still considered competitive in 1990, the performance of its Kayaba shock left a lot to be desired. Choppy and harsh on small stuff, and too easy to bottom on the big stuff, it offered the worst performance in the 500 class. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

| With a talented rider like Rich “Spuds” Taylor aboard, the YZ490 could be made to shred, but doing so took skill and commitment. The tall tank made getting forward a challenge, while its erratic low-speed jetting and sedate steering geometry made carving smooth arcs difficult. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider |

|

| Fred Flintstone: While the front brake on the YZ490 was adequate, its rear drum was less than so. Big and powerful bikes need good brakes, and the rear binder on the 490 was not nearly good enough. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

For 1990, the YZ490 walked into its final season with only a set of stripes on the seat and a set of red bars to differentiate it from its 1989 predecessor. The dreamed of liquid-cooled YZM replica über-500 never materialized and Yamaha loyalists were left to soldier on for one last season with the air-cooled and drum-braked YZ490. It still detonated on top, blubbered off the bottom and vibrated like something had to be wrong, but proved nearly indestructible as long as you ran a 50/50 mix of race gas to keep the pinging under control.

|

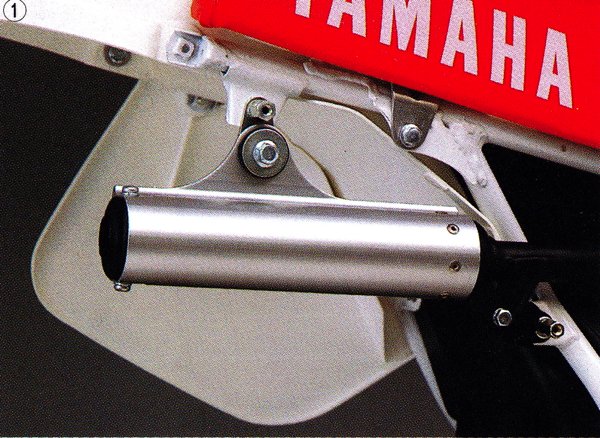

| Although aluminum and repackable, the stock silencer on the YZ490 was not particularly effective at quieting the big 490. When you added in the ringing of the YZ’s cooling fins, you had by far the loudest 500 on the track. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

|

| In 1991, Yamaha gave the YZ490 one last hurrah by reintroducing it as the WR500. Basically a 1991 YZ250 chassis with an air-cooled YZ490 motor shoehorned in, the WR was good enough to take Damon Bradshaw (number 11 above leading KTM’s Mike Fisher) to victory in the first moto at Broome-Tioga in 1991. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

Compared to its 500 competition in 1990, the YZ490 was actually heavier than the liquid-cooled machines and offered less power overall. Its top-end-focused powerband seemed to skew it toward the expert end of the spectrum, but by 1990, no self-respecting pro was going to be caught dead on a YZ490. By this point, even Yamaha’s Factory team had abandoned the old air-hammer and moved on to racing Öhlins-kitted YZ360s instead. With head mods and some quality gas, it still made a decent play bike and a solid desert sled, but the excessive vibration, old-school handling and sub-par brakes made it a tough sell for motocross. In 1991, the old girl would enjoy one last day in the sun as the reborn WR500. The WR was basically the old YZ490 motor, stuffed into a modern YZ250 rolling chassis. While capable enough to take Damon Bradshaw to a moto victory at Broome-Tioga in ’91, the WR would only last two years in Yamaha’s lineup before being retired for good at the end of 1992.

|

| At $3599, the YZ490 was the least-expensive 500 you could buy in 1990. For that money, you got a reliable, easy-to-work-on, do-it-all machine that was equally at home in the desert or on the track. It was not the fastest, quickest-turning or most-refined Open bike you could buy, but with a few simple mods, it made an excellent all-around racing machine. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

While the YZ490 went out with a whimper instead of a bang in 1990, its heritage as an icon of 1980s motocross is secure. In 1985, it was good enough to take Broc Glover to the 500 National Motocross championship (against maybe the trickest 500 two-stroke of all time) and in 1987, it took Jeff Stanton to second in the 500 Nationals behind the virtually unbeatable Ricky Johnson on his Factory Honda CR500R. It was a flawed bike, but a surprisingly capable one. Yes, there were faster 500s available, and it did burble, pop and ping, but with the some simple mods and some careful setup, it became a formidable motocross weapon. If the CR500R was a Ferrari, then the YZ490 was a Boss 302 Mustang. Crude and old-fashioned, yes, but still able to get the job done when the lights went green and it was go time.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com