For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new for 1988 CR250R.

In 1988, Honda retired the most successful machine in motocross in favor of a controversial and supercross-bred redesign. Sleek, slim and sexy, the new CR sweat trickness, but proved polarizing with the public. Photo Credit: Honda

The mid-eighties were a great time for Honda. After a bumpy start in the first few years of the decade, they came roaring back with a string of shootout-winning hits and iconic machines. Bikes like the ‘83 CR480R, ’86 CR250R and ‘87 CR125R still stand as some of the best bikes ever built in their respective classes. In the mid-eighties, you were riding red, or you were playing catch-up.

In 1987, Honda had dominated the 250 standings with a rocket-fast motor and superb forks. Unfortunately for the Honda faithful, however, neither of those assets would be available to fall back on in 1988. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1987, Honda once again dominated the charts with an incredible lineup of machines. From 80cc to 500cc, the CRs were nearly unbeatable with their blisteringly-fast motors and razor-sharp handling. None of them had great shocks, and they shook at speed like the front wheel was about to come off, but for hard-core motocross, they were hard to beat.

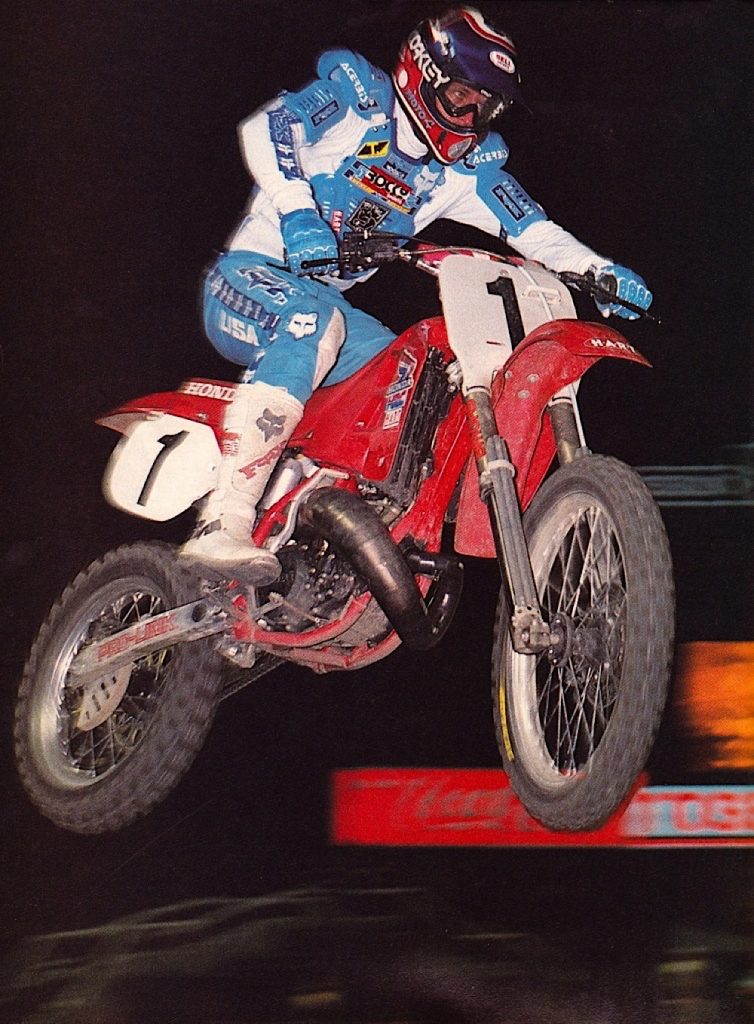

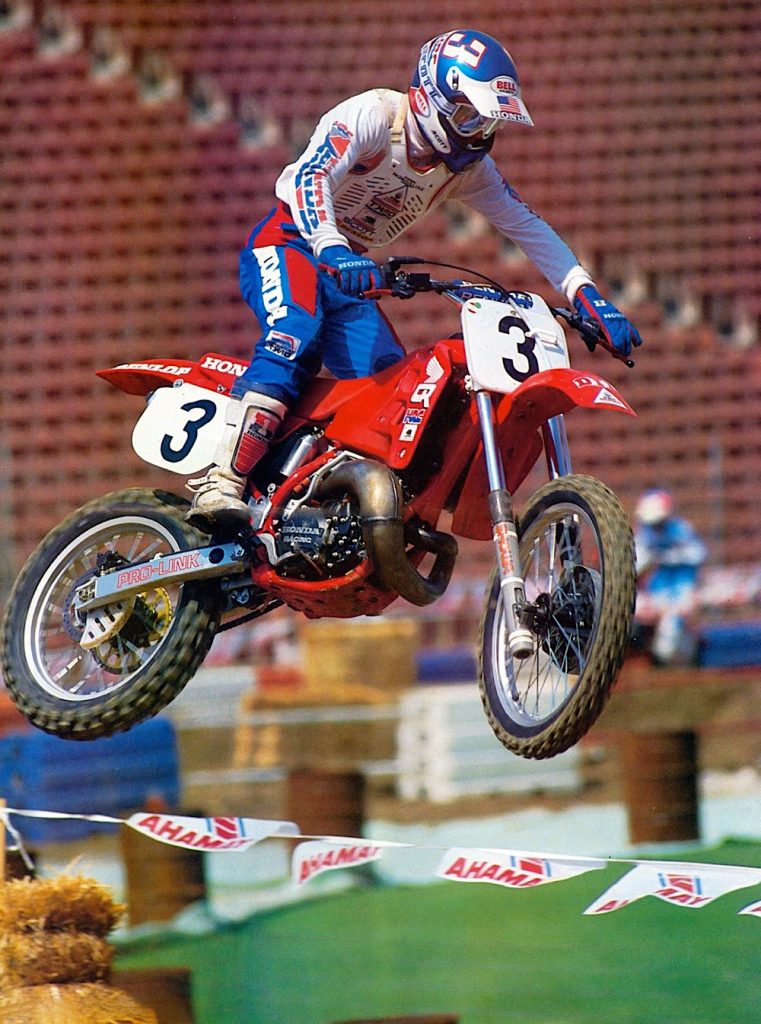

Bad Boy: There can be little doubt that most of the changes made on the ‘88 CR250R were aimed at one thing: winning Ricky Johnson another supercross title. A new stouter frame, beefier linkage and super-slim layout made the ’88 CR250R the perfect platform from which to build a championship-winning machine. Photo Credit: Super Motocross

For 1988, Honda chose to stand pat with their 80, 125 and 500 machines. On those models, a color swap from “Flash Red” to “Fighting Red” and a new silver cylinder were the most prominent changes. On the 250, however, it was time for a major redesign of one of the most successful machines in motocross.

In 1988, both the Honda CR250R and YZ250 were all-new and ready to claim your hard-earned cash. In modified form (as here, with Rich Taylor and Wild Willy Simons onboard a couple of Dirt Rider’s test units), both were incredibly effective, but the Yamaha was the better stock machine. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

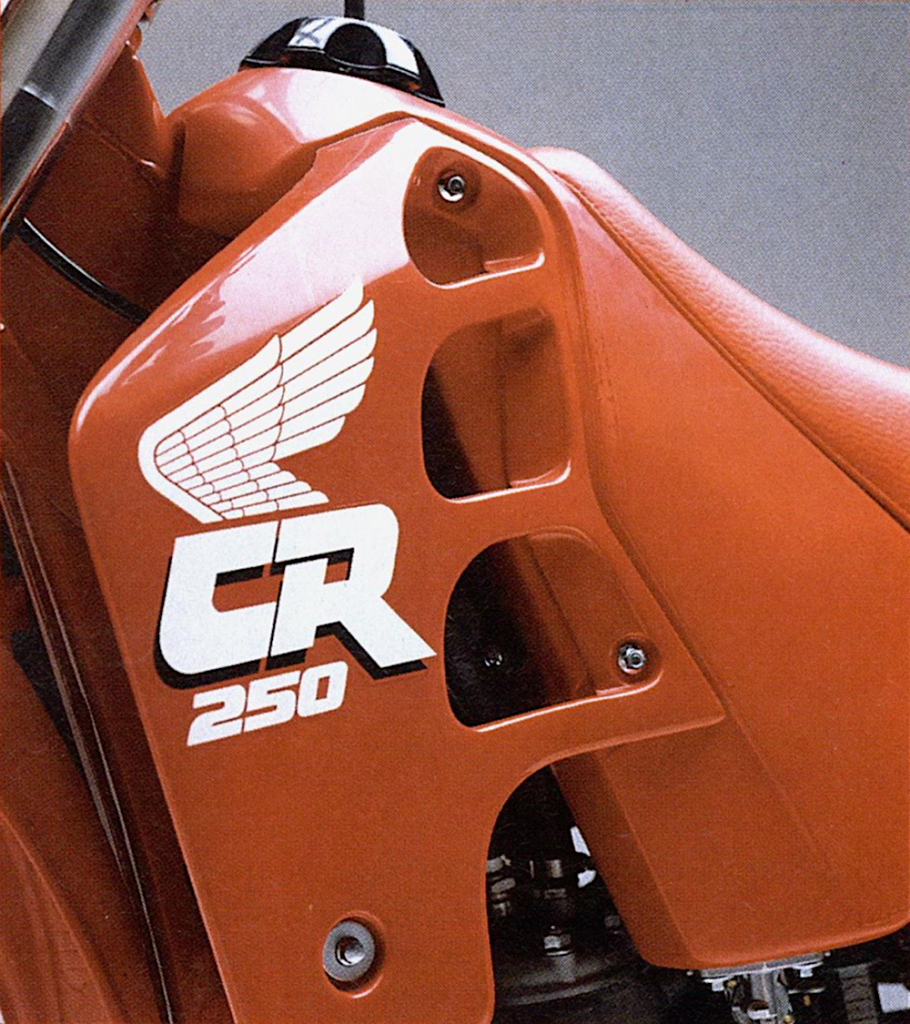

Visually, the new CR250R looked quite different than the machine that had taken Ricky Johnson to the 1987 AMA 250 Motocross title the year before. In addition to the new deeper red color, the redesigned CR featured striking new bodywork that made it look like the equivalent of a two-wheeled Ferrari. Sleek and low-slung, the new tank harkened back to the days of Honda’s unobtainable works bikes of the early eighties. Mated to that tank were a new longer and flatter seat that carried all the way up to the gas cap and an odd-looking new “low boy” exhaust that bulged out, instead of up. While the side plates, front fender, rear fender and fork boots were a carry over from ’87, the new color scheme gave them all a fresh look.

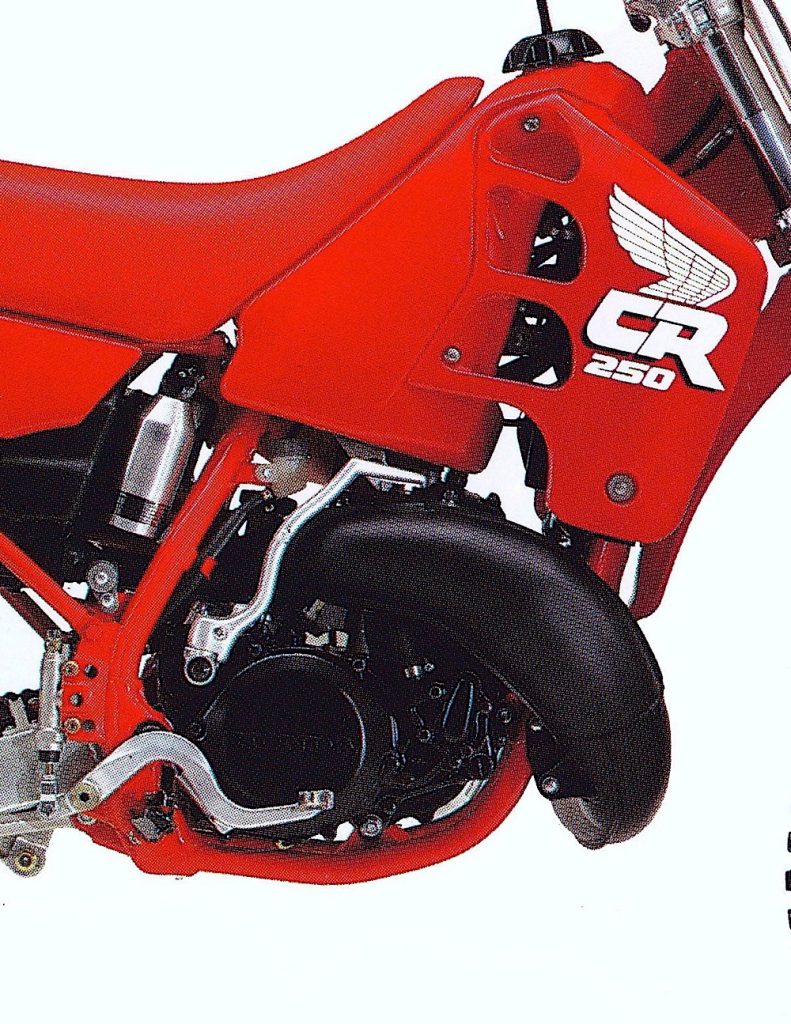

A new “low-boy” exhaust system for 1988 lowered the bike’s center of gravity and moved the exhaust away from the shock to help reduce fading. While the new pipe allowed the pilot compartment to be slimmer (and reduce inner thigh roasting), the increased width of the new design made it more vulnerable to crash damage in a tip-over. Photo Credit: Honda

A new “low-boy” exhaust system for 1988 lowered the bike’s center of gravity and moved the exhaust away from the shock to help reduce fading. While the new pipe allowed the pilot compartment to be slimmer (and reduce inner thigh roasting), the increased width of the new design made it more vulnerable to crash damage in a tip-over. Photo Credit: Honda

Underneath the sexy new bodywork, Honda also had a long list of technical changes on tap for 1988. A new frame was spec’d that lowered the center of gravity, reduced weight, and improved handling. The main frame backbone sat a full inch lower than the ’87 and the swingarm pivot was fully boxed for the first time to reduce flex. The wheelbase was shortened by an inch and the geometry was altered slightly to improve turning and (hopefully) reduce the CR’s notoriously-bad headshake when coming down from speed.

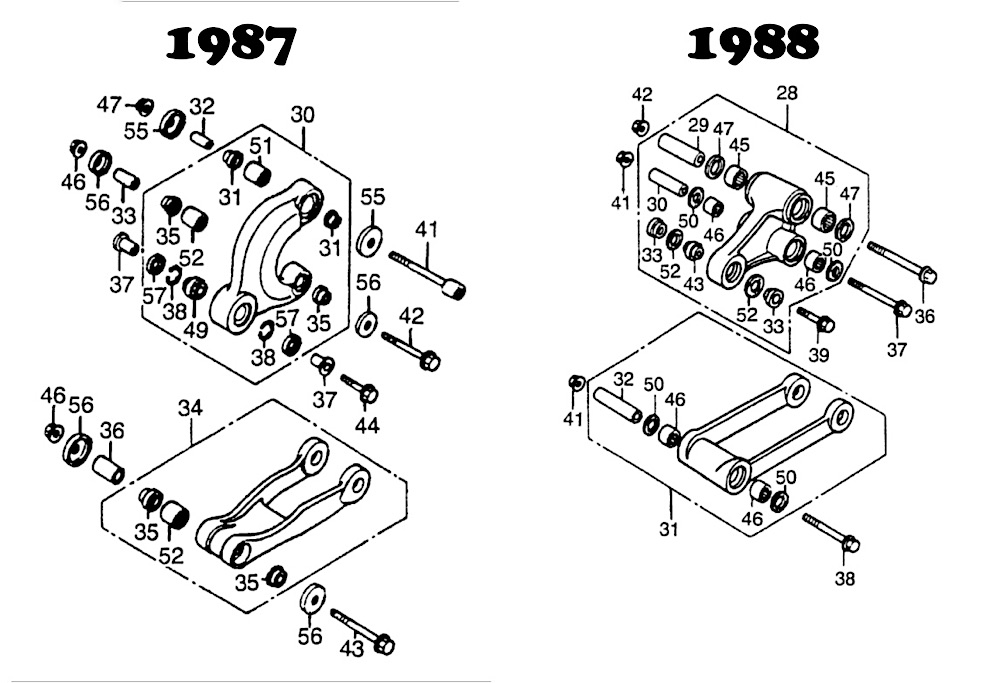

Delta Link: For 1988, an all-new linkage was designed for the CR250R that reduced weight, increased rigidity and lowered the bike’s center of gravity. Photo Credit: Honda

On the suspension front, the new CR250R retained the award-winning 43mm Showa conventional cartridge forks of the ’87, but added new valving and a change in spring rate to match the new chassis. Out back, Honda ditched the fade-prone Showa “piggy-back” shock of 1987 in favor of an all-new design that moved the reservoir from under the seat (where it received very little cooling air) to the side of the shock body. Mated to the new shock was a completely redesigned Pro-Link linkage and beefed-up alloy swingarm.

Idaho’s Rich “Spuds” Taylor demonstrating the new CR’s light and flickable nature for Dirt Rider magazine. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

The highlight of the new linkage was a redesigned bellcrank that was intended to improve performance on hard hits and reduce flex under heavy loads. Coined the “Delta Link” (for its delta shape), this new linkage was aimed at tackling the type of Supercross obstacles that were becoming more common even at the local level. The new swingarm was also redesigned and consisted of fewer individual pieces than before. By using a new pressure-cast “hybrid” construction, Honda was able to make the new swingarm both lighter and stronger.

A switch to “Fighting Red” from the orange-red of 1987 gave all the 1988 CRs a bold new appearance. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

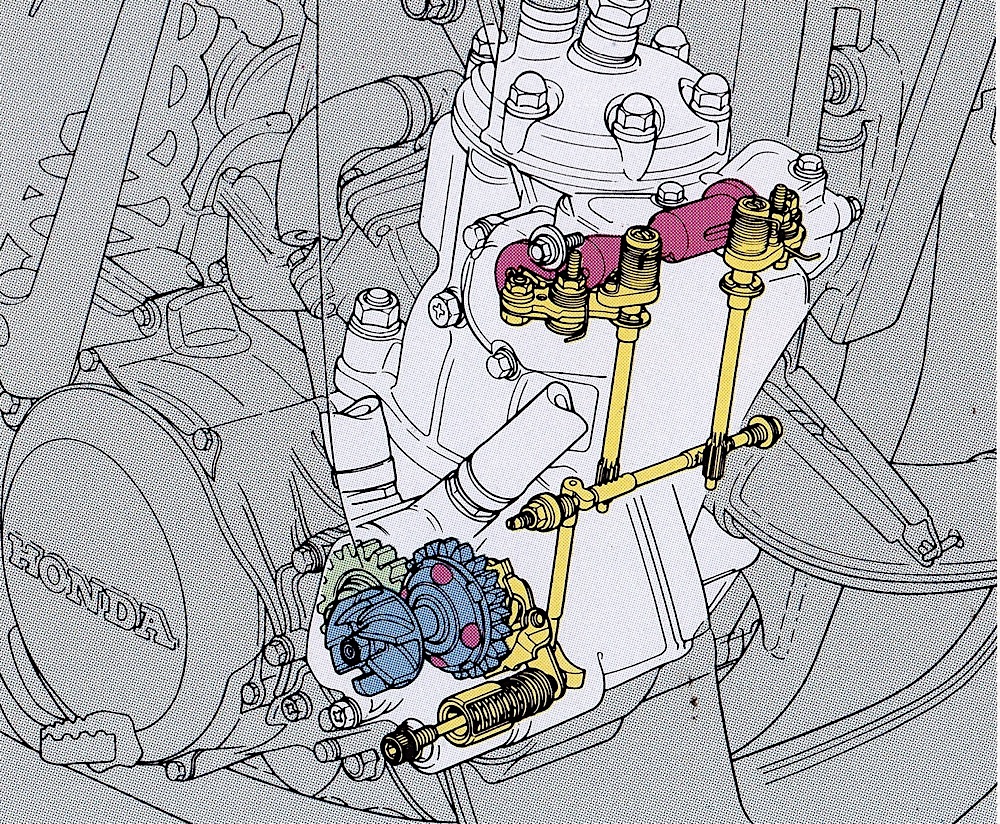

On the motor front, Honda stuck with the same basic Honda Power Port (HPP) design they had used since 1986. While complicated and maintenance intensive, the HPP system was very effective at producing a broad and potent powerband. In 1987, the CR250R had offered a brutal blast in the midrange and a screaming top-end hook. It was loved by experts, but somewhat intimidating to less-skilled pilots. For them, the smoother ’86 powerband was preferable. For 1988, Honda aimed to bring back a bit of the ‘86’s broad delivery and mate it with the ‘87’s scalding top-end thrust.

Milk Bottle: In 1987, one of the CR250R’s few faults was the performance of its rear shock. The peculiar “piggy-back” Showa shock buried the reservoir under the seat and away from any cooling air. Predictably, this led to fade, so for 1988 Honda bolted on a new unit that moved the reservoir back outside the bodywork. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In order to achieve this, the Honda engineers spec’d a new cylinder, massaged the HPP system and lightened the flywheel. New porting in the cylinder lowered the intake port .5mm and increased overall exhaust port area. In the HPP, Honda extended the valves to cover more of the exhaust port when closed and changed the linkage to open wider at full tilt. The centrifugal-ball governor was also modified to open at an earlier rpm and the ignition was rewired to provide a hotter spark. Internally, the CR remained a five-speed, but new ratios (identical to 1985) tightened the spaces between the cogs.

While not changed as much as the rest of the bike, the 249cc motor on the CR250R did receive some subtle, but important updates for ’88. The HPP (Honda Power Port) system remained, but new porting increased the overall port area of the intake and exhaust. The HPP was also tuned to open wider and engage sooner. When combined with a new intake and exhaust, the overall power profile of the ‘88 CR turned out to be very different than the ‘87. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1987, the CR250R had suffered some reliability issues, so Honda made a few changes for ’88 to address these problems. Both the upper and lower rod bearings were beefed up and a new piston was installed with a stronger crown and new low-friction rings. The cylinder remained NiCaSil-plated, which meant excellent heat transfer characteristics, but no over-boring if there was an issue. The intake was modified to seal better and a new four-pedal reed-valve (the ’87 used a six-pedal) was installed and mated to a redesigned airbox. The airbox offered a larger volume for ’88 and featured a new dual-stage filter to help prevent dirt and dust from making its way into the motor’s more delicate parts. The carburetor remained a 38mm “flat-slide” Keihin, and offered new jetting to match the revised motor settings.

In 1988, Rick Johnson was at the peak of his powers on the new CR250R. He would win eight main events on his way to his second AMA 250 Supercross title. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

On the track, the new Honda turned out to run completely differently than the ’87 CR250R. Gone was the explosive hit and blistering acceleration the CR had become famous for. Instead, the ’88 version pumped out a slow-building and electric style of power that offered no hit whatsoever. Top end power was still strong, but the lethargic delivery made it feel slow. The actual spread of the power was quite impressive and it pulled over a broader range than in ‘87, but most riders preferred the snap of the year before.

On the track, the new CR250R turned out to run the exact opposite of the potent ’87 version. Unlike the year before, there was no burst and no hit, just a slow-revving electric flow of power that looked impressive on the dyno, but felt slow on the track. Top-end power was still plentiful, but the languid way it got there had many people wishing they had just left the motor alone. Photo Credit: Honda

While low-end power was improved for ’88, some of that gain was mitigated by the CR’s atrocious stock jetting. As delivered, the CR burbled off the bottom and fouled plugs like a mosquito fogger. Once leaned out, it ran much better, but tended to ping on pump gas when ridden hard. Just to be safe, a 50/50 mix of race gas was advisable.

While the motor lacked snap, the overall feel of the 1988 CR was without peer. Whether in the air or on the ground, nothing in the 250 class felt as light and nimble as the Red Rooster. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1988, George Holland was Rick Johnson’s teammate on the all-new CR. Interestingly, unlike RJ, Holland chose to stick with conventional forks on his Factory CR instead of going with the works inverted Showa units RJ preferred. Photo Credit Kinney Jones

On the suspension front, things were once again a step in the wrong direction. In 1986 and 1987, Honda had dominated the fork wars with their works-like Showa cartridge sliders. They were head-and-shoulders better than the damper-rod-equipped competition and a huge advantage for the red team. By 1988, all of the CR’s competition had moved on to cartridge internals and they were no longer the advantage they had once been.

Hero to zero: In 1986 and 1987, Honda had ruled the fork wars with their works-like Showa 43mm cartridge forks. For 1988, all that changed with a new internal valving design and some poorly-chosen settings. Too light on compression and too heavy on rebound, the ’88 version of Honda’s world-beaters packed down under braking and crashed to the stops on jumps. These were easily the worst forks in the ‘88 250 class. Photo Credit: Honda

In addition to this stiffer competition, Honda faced setbacks of their own making in 1988. The new tapered two-stage valving and springs chosen at the Honda factory ruined what had previously been the best forks in the business. They packed under braking, bottomed over jumps and generally beat you to death everywhere in between. There was too little compression damping, not enough spring rate and too much rebound. Once the Jedi Knights of the moto wars, Showa’s wave washer units took a turn toward the Dark Side in 1988.

After utterly dominating the 250 class for two years, it was Honda’s turn to take a beating in 1988. None of the major magazines picked it any better than third, and most of them rated it as last. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Out back, the Delta Pro-Link did not fare much better and offered a punishing ride at anything below a flat-out pace. That new linkage worked well on supercross whoops and big hits, but at moderate speeds, it pounded the rider to death. On an outdoor track, it hopped and skipped under power and hit a wall of damping midway through the stroke. If you were Rick Johnson and slammed into stuff like a man possessed, it worked well, but if you backed off to a mere mortal pace, it kicked, bucked and protested.

Hammer head: The all-new Pro-Link rear suspension on the CR turned out to work only marginally better than the unloved 1987 version had. The new Delta Link provided a punishing ride on anything not resembling a supercross track and never quite settled down in the rough. Photo Credit: Photo Credit: Honda

While the motor and suspension changes for ’88 met with lackluster reviews, the rest of the CR package was an unqualified hit. The new layout was razor thin and far easier to move around on than the ’87. The seat, bars, grips and controls were the class standard and nothing on the track was as comfortable as the red machine. Even though the bike was only one pound lighter on the scale, it felt close to fifteen pounds lighter on the track.

While plenty of people had issues with the CR’s motor and suspension, no one had any complaints with the bike’s handling. Light, airy and almost 125-like, the CR could carve over, under and around any other deuce-and-a-half on the track. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

That excellent rider position and light feel paid major dividends on the track. Compared to the other machines in its class, the new CR felt like a feathery 125. It was tossable in the air and nimble on the ground. Turning was incredibly accurate and the CR could carve underneath any other 250 on the track. With its excellent ergonomics and slim pilot compartment, getting forward for turns was a piece of cake and the pilot always knew what the front wheel was doing. Unfortunately, sometimes, that also included oscillating from lock-to-lock. While more stable than before, the new CR continued its predecessor’s habits of breaking into fits of headshake. Once the suspension was sorted, the CR became less sketchy, but its propensity to develop the shakes never went completely away.

One notable change on the 1988 CR was the switch from braided steel to plastic for the bike’s brake lines. While not as highly regarded in general, the new lighter and cheaper material did not seem to make any appreciable difference in the CR’s class-leading braking performance. Photo Credit: Honda

Detail-wise, the new CR continued to lead the class with excellent quality in most areas. Both the fit and finish of the bodywork and quality of the fasteners holding it on were a cut above the competition. The quality of the stock grips (the only ones in the class worth leaving on the bike), bars (tough chromoly steel that was actually stronger than the aluminum Renthals of the era) and levers also led the field. In spite of a switch from braided steel to plastic for the brake lines, the CR also continued to dominated the brake wars. The clutch and transmission were also praised for their durability and feel. Unlike most other brands of the era, missed shifts were all-but-unheard-of on the CR.

Delta-fail: In addition to pounding your back side, the new Delta Link turned out to be a big fan of bending linkage bolts. Photo Credit: Honda

While the new CR proved reliable overall, there were a few first-year issues. Probably the most glaring of these problems was with the new Delta Link. Not only did it not work particularly well, it also took to bending linkage bolts at regular intervals. Once bent, getting them out could be a nightmare, and if you replaced them with more OEM bolts, they were sure to bend again. The new dual-stage air filter also proved to not be long for this world. After a few washings, the glue gave up the ghost and you were stuck with a single-stage filter (if you were lucky) or no filter at all (if you weren’t). Once breathed on, the stock motor also lost a good bit of its indestructability. Many people went looking to the aftermarket in search of the old motor’s punch, and quite a few ended up with blown crankshafts for their trouble.

In 1988, Honda took a major step into the future with a totally redesigned CR250R. Instead of playing it safe, they took the most-popular machine in motocross and took it in a completely new direction. Slim, sleek and supercross-focused, the ’88 CR250R was a machine with almost unlimited potential, but in need of another year of refinement. Photo Credit: Honda

Overall, the 1988 Honda CR250R turned out to be a step forward in some areas, and a step backward in others. The new CR drew rave reviews for comfort, style and handling, but left most riders cold in the motor and suspension department. The super-thin and sleek layout certainly pointed toward the future of motocross design, but its lazy motor and harsh suspension were a throwback no one was looking for. With some motor work and suspension tuning, it was capable of winning at the sport’s highest levels, but in stock trim, the 1987 CR250R was probably a better machine.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com