For this edition of Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s first perimeter-framed tiddler, the 1990 KX125.

Buck Rogers: In 1990, Kawasaki sent eyes bulging and tongues wagging with the introduction of their radically-new KX125. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Buck Rogers: In 1990, Kawasaki sent eyes bulging and tongues wagging with the introduction of their radically-new KX125. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1990, no machine in motocross was as jaw-droppingly cool as Kawasaki’s all-new KX125 (excluding, of course, its similarly badass 250 stablemate). Audacious in appearance and innovative in design, the new KX125 was a radical departure from the stodgy green machines that had come before it. Borrowing liberally from their road-race department, the new KX125 broke new ground in frame design, mass centralization, and styling. Maybe most importantly, it was not just innovative, it was downright sexy.

Your father’s Oldsmobile: Compared to the cobby-looking ’89 KX, the ’90 machine appeared to be from a decade into the future. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Your father’s Oldsmobile: Compared to the cobby-looking ’89 KX, the ’90 machine appeared to be from a decade into the future. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For Kawasaki, this was certainly something that had seldom been said about their 125 offerings. While some of them had been fast, they had rarely been beautiful. With their comically large rear fenders, weird proportions and single-sided radiators, the KX125s were most often the ugly ducklings, instead of the belle of the ball.

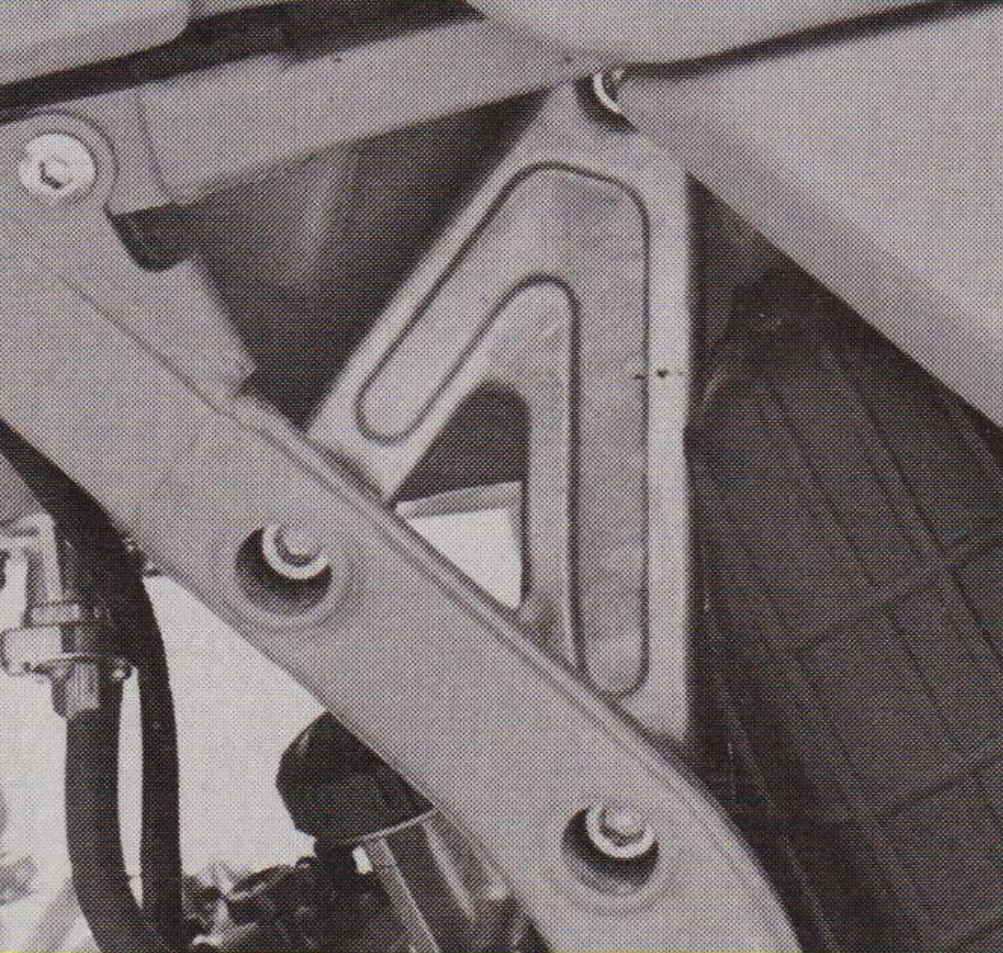

By far the most radical change on the 1990 KX was in the configuration of its frame. Borrowing liberally from the street world, Kawasaki designed an all-new steel frame that did away with a traditional backbone, in favor of two large spars that flanked the motor in a perimeter fashion. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

By far the most radical change on the 1990 KX was in the configuration of its frame. Borrowing liberally from the street world, Kawasaki designed an all-new steel frame that did away with a traditional backbone, in favor of two large spars that flanked the motor in a perimeter fashion. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

For 1990, all that finally changed with an all-new KX125. Unlike previous green machines, this new KX positively sweat trickness from its every pore. With bold styling, a radically new frame design and innovations throughout, the 1990 KX marked the most dramatic year-over-year change in the brand’s history.

Plug and Play: Because the new frame did away with the frame backbone, a new tank needed to be designed that sat nestled between the main frame spars. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Plug and Play: Because the new frame did away with the frame backbone, a new tank needed to be designed that sat nestled between the main frame spars. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While nearly everything on the 1990 KX125 was a dramatic departure from the past, probably the most significant change was in the design of the frame. In the late eighties, the state-of-the-art in motocross frame design was a large single backbone, mated to a lower engine cradle and rear sub-frame. On some bikes, the rear sub-frame was fully removable, while others only offered a single frame tube that could be removed to aid with shock access. In every case, the frame was made from high strength steel (the only exception being the rear sub-frames, which were usually crafted out of aluminum).

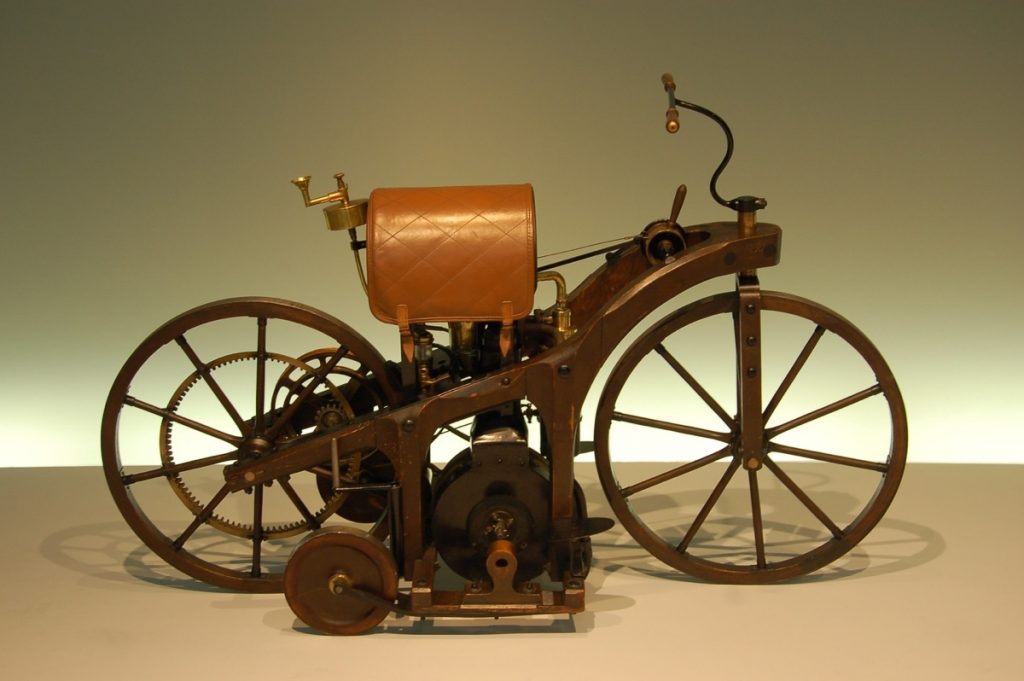

While new to motocross, the idea of a perimeter-framed motorcycle was hardly a novel concept. In truth, the design dated all the way back to 1885, with the introduction of world’s first true motorcycle, the Daimler Reitwagen.

While new to motocross, the idea of a perimeter-framed motorcycle was hardly a novel concept. In truth, the design dated all the way back to 1885, with the introduction of world’s first true motorcycle, the Daimler Reitwagen.

Photo Credit: Mercedes Benz

In use for decades with some minor variations, this basic frame design had proven itself incredibly effective at handling the extreme demands placed on an off-road chassis. Over the years, the quality of the steel had improved, and manufactures had played with geometry, tube thickness and engine cradle design, but for the most part, this basic configuration had remained the gold standard since the early days of motocross.

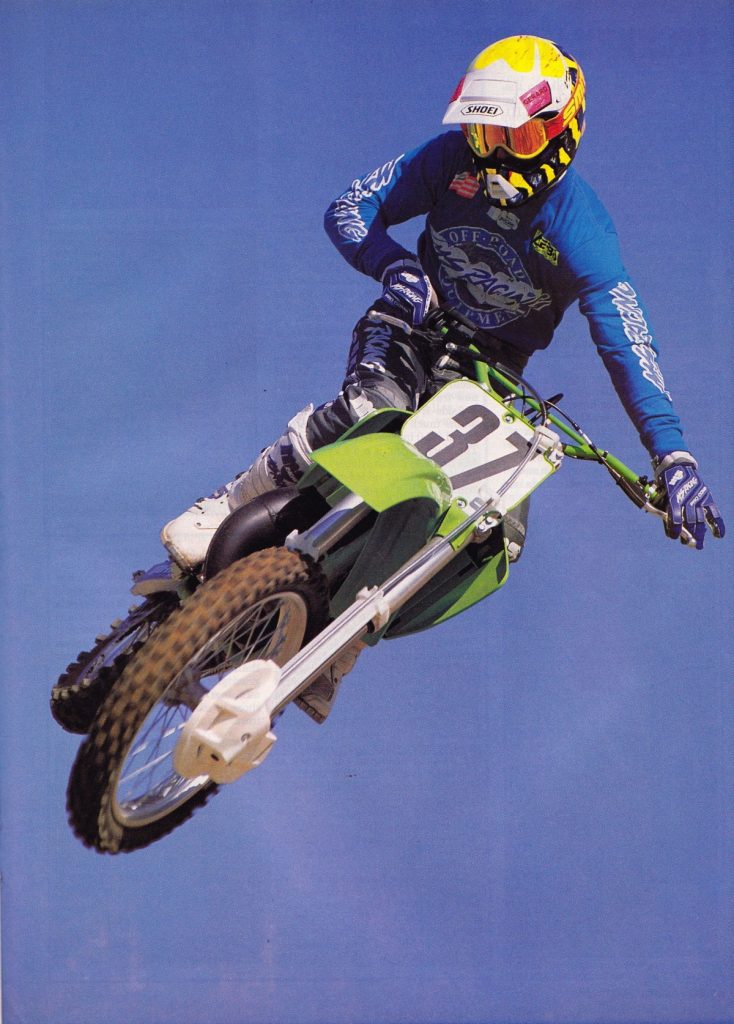

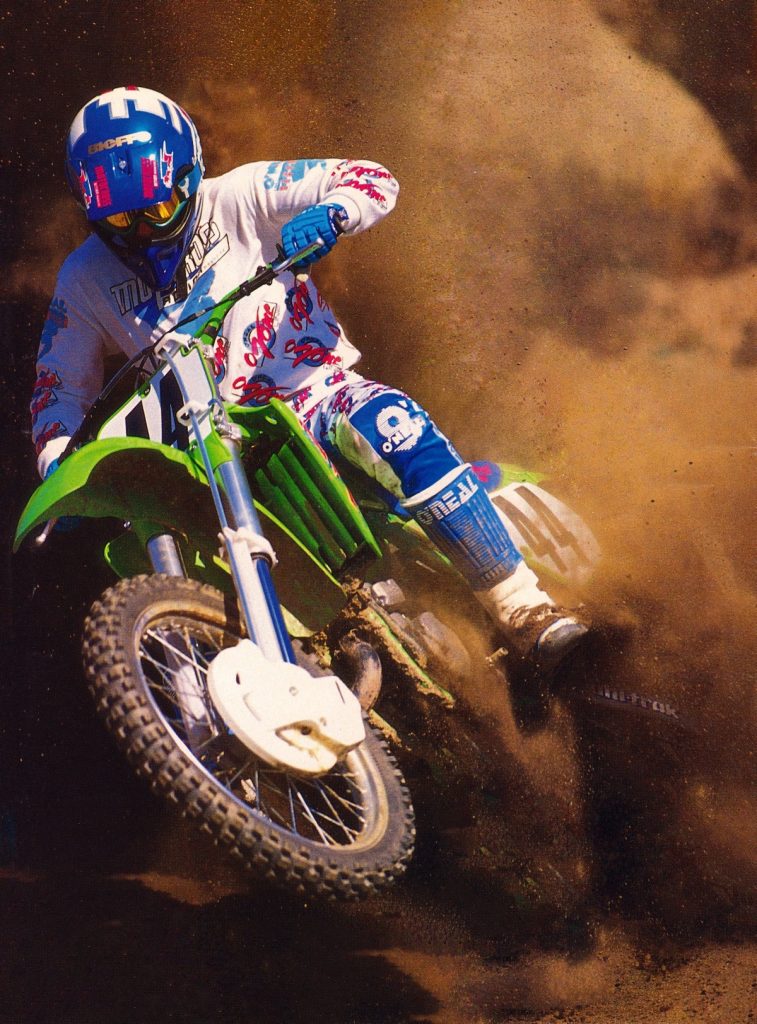

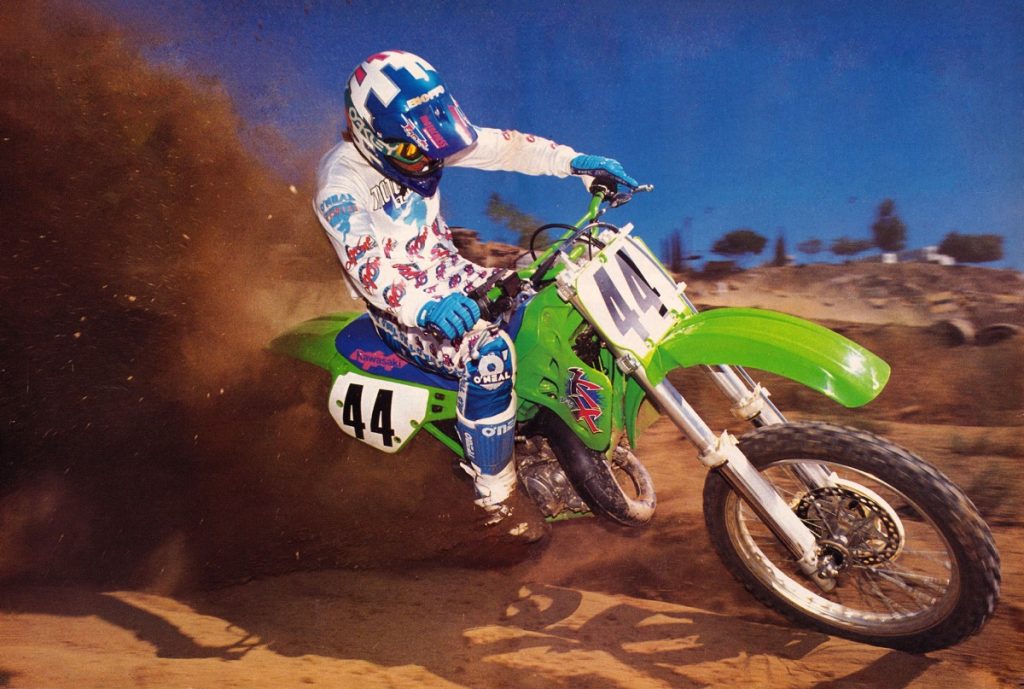

At 202 pounds, the new KX was larger and heavier than all of its competition. In the air, it felt much more like a typical 250 than a featherweight 125, but a talented rider like Radical Rich Taylor could still bend it to his will. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

At 202 pounds, the new KX was larger and heavier than all of its competition. In the air, it felt much more like a typical 250 than a featherweight 125, but a talented rider like Radical Rich Taylor could still bend it to his will. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

For 1990, Kawasaki threw all of this out the window with the most radical departure in chassis design since the switch to linkage-equipped rear suspensions a decade before. Borrowing heavily from their road race department, Kawasaki spec’d an all-new frame that did away with the large single backbone and replaced it with twin-beams that split at the steering head and ran down both sides of the machine. Often referred to as a “perimeter” design, this configuration had been used on-and-off on street machines for over a century. The main benefits of the perimeter design were its strength (very resistant to torsional flex) and packaging (no backbone to work around) advantages.

Sing the high note: In the engine department, the new-look KX was pro-oriented and blisteringly fast. Low-end power was all but nonexistent, but once it hit the midrange, it was Katie bar the door. In 1990, only Honda’s similarly high-strung CR125R had a prayer of keeping the green machine in sight. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Sing the high note: In the engine department, the new-look KX was pro-oriented and blisteringly fast. Low-end power was all but nonexistent, but once it hit the midrange, it was Katie bar the door. In 1990, only Honda’s similarly high-strung CR125R had a prayer of keeping the green machine in sight. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

When designing the new perimeter frame for the KX, Kawasaki had elected to stick with steel instead of going to aluminum for its construction. While common on sport bikes of the time, this was still early days for alloy usage in the dirt, and durability remained a major concern for the engineers. While light and strong, aluminum could be tricky to work with and many feared an alloy frame might crack under the repeated poundings of a motocross course.

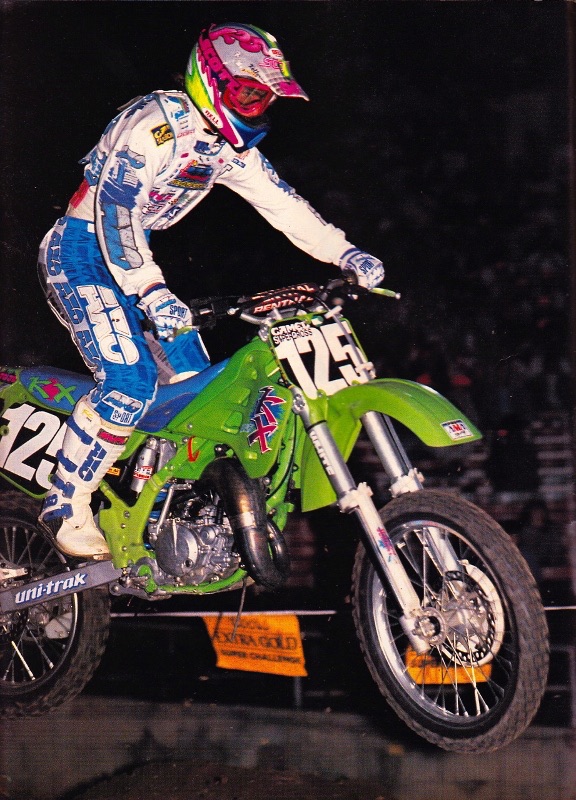

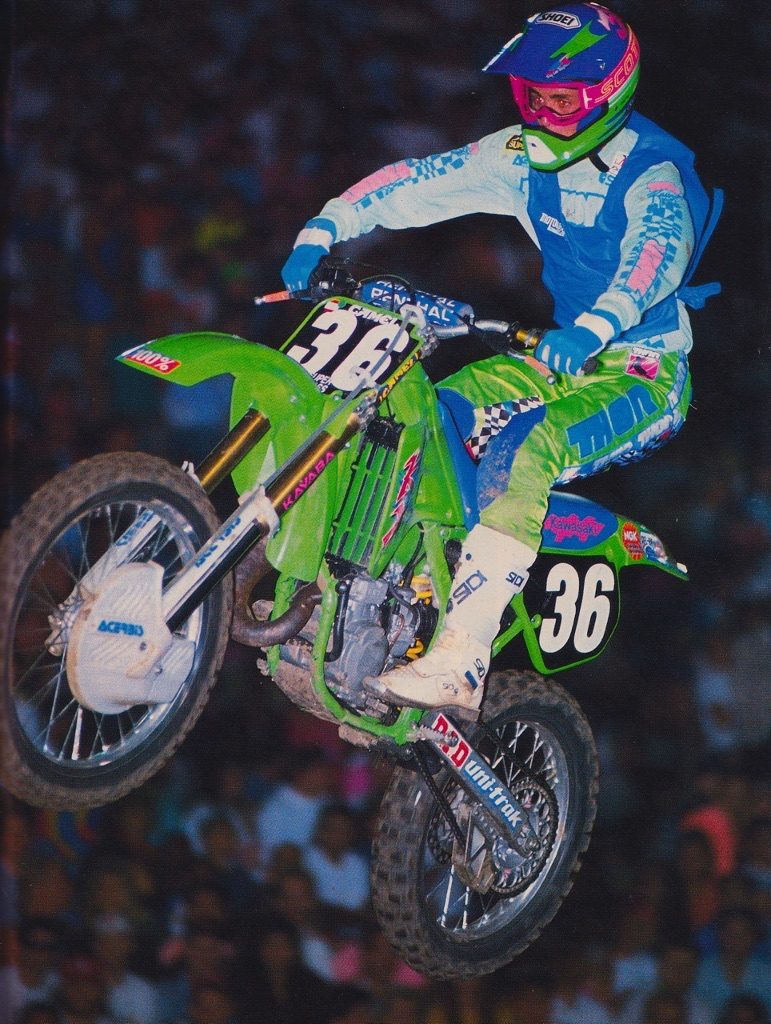

In 1990, a little-known Team Green kid by the name of Jeremy McGrath took the new KX125 to his first Supercross win at Las Vegas. Photo Credit: MXA

In 1990, a little-known Team Green kid by the name of Jeremy McGrath took the new KX125 to his first Supercross win at Las Vegas. Photo Credit: MXA

When designing the new frame, Kawasaki decided to use a mix of round and boxed-section tubes for its perimeter construction. The engine cradle, side rails and steering head were all formed from chromoly steel, with only the subframe and shock tower being constructed out of aluminum. In a unique touch, the shock tower was also removable and replaceable if damaged.

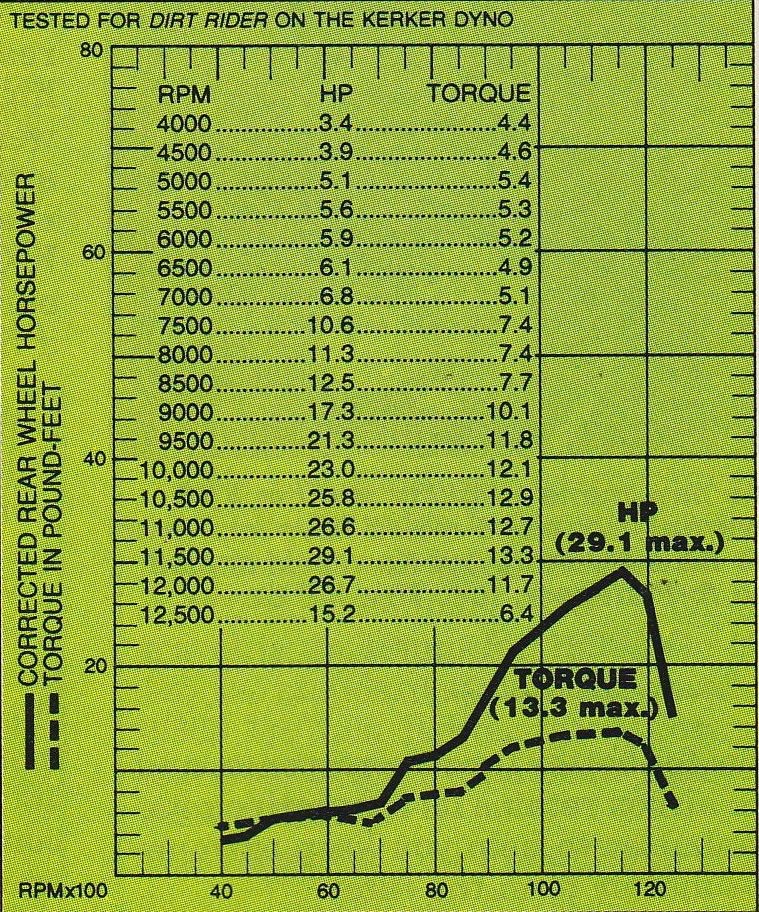

At 29.1 horsepower, the 1990 KX125 was the most powerful 125cc machine Dirt Rider had tested up to that time. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

At 29.1 horsepower, the 1990 KX125 was the most powerful 125cc machine Dirt Rider had tested up to that time. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Overall geometry was completely new, with a steeper head angle (25.5 degrees vs. 26.5 in ‘89) and a .6-inch reduction in wheelbase. With the backbone being removed, Kawasaki was also able to design a new fuel tank that sat lower in the chassis, between the two frame spars. Fuel capacity was slightly lower for 1990, going from 2.3 gallons in ’89 to 2.25 gallons in ‘90. In order to accommodate the new frame, revamped bodywork was spec’d that did away with the old bike’s frumpy looks and replaced them with sleek lines and spacy graphics.

While powerful, the KX’s lack of low end and strong hit could make it a bit of a handful for those of lesser talent to manage. For beginners and novices, the Suzuki RM and Yamaha YZ probably made better choices. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

While powerful, the KX’s lack of low end and strong hit could make it a bit of a handful for those of lesser talent to manage. For beginners and novices, the Suzuki RM and Yamaha YZ probably made better choices. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The second major change on the KX125 for 1990 was the switch from Kayaba’s excellent 46mm conventional forks to their still-unproven 41mm inverted units. In 1989, international buyers had gotten the upside-down sliders, but Kawasaki USA had decided to stick with the old-fashioned hardware until the bugs were worked out. Like the new frame, the inverted forks were designed to reduce flex and provide better feel in whoops and other high G-load situations. Out back, the rear suspension remained largely unchanged, with a KYB shock and Uni-Trak linkage handling the duties. Travel remained at 13 inches, but the new system did improve ground clearance 15mm by relocating the shock mounting.

In 1990, no bike was as polarizing as Kawasaki’s new KX125. Basically, you either loved it or hated it, with very little in between. Just look at the rankings of Motocross Action and Dirt Bike’s shootouts, which ranked the KX first (MXA) and last (Dirt Bike) in their standings. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1990, no bike was as polarizing as Kawasaki’s new KX125. Basically, you either loved it or hated it, with very little in between. Just look at the rankings of Motocross Action and Dirt Bike’s shootouts, which ranked the KX first (MXA) and last (Dirt Bike) in their standings. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Perhaps more than any other bike in the class, the 1990 KX125 rewarded aggression and penalized timidity. Credit: Mike Kroger

Perhaps more than any other bike in the class, the 1990 KX125 rewarded aggression and penalized timidity. Credit: Mike Kroger

On the motor end, Kawasaki retained the same basic 124cc case-reed mill it had used since 1988, but made several important changes aimed at improving power. The first modification was a switch to a concave piston with a single ring for reduced drag and a cleaner burn. Then the KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System) was redesigned to eliminate the use of a variable exhaust port and instead only vary the position of the scavenging boost ports. The exhaust resonance chamber was retained and it remained in its prominent position on the outside of the cylinder. To improve combustion, a second coil was added and mated to a new microprocessor-controlled digital ignition. The carburetor remained a 35mm Keihin PKW, but a new “jet block” was added to the bottom of the venturi to reduce intake turbulence. Feeding the revised carburetor was a new larger air boot and airbox, with innovative shutters that could be opened and closed based on conditions to let in more air, or keep out water.

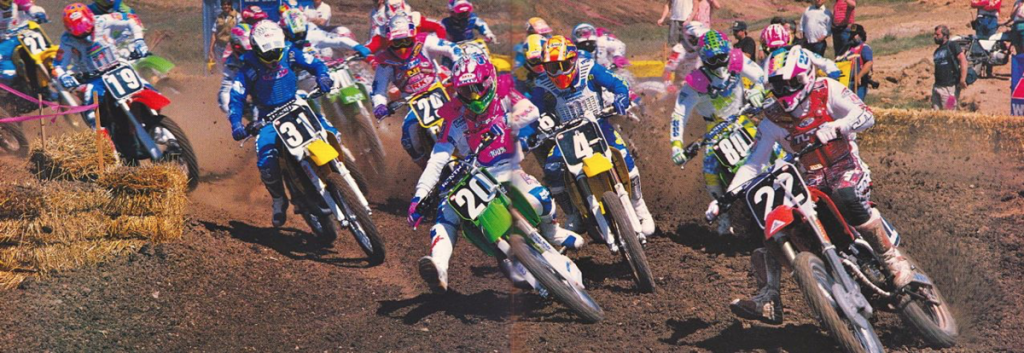

In 1989, KX pilots had been at a major power disadvantage to the other bikes in the class. In 1990, riders like Jeff Matiasevich (20) finally had the power to run at the front. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1989, KX pilots had been at a major power disadvantage to the other bikes in the class. In 1990, riders like Jeff Matiasevich (20) finally had the power to run at the front. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the exhaust side, the motor featured a new “low-boy” pipe that sat farther down on the chassis and a sano new alloy muffler with a large oval body and turned-down tip. Keeping the motor cool were a set of dual (finally!) radiators that increased capacity, improved ergonomics and did wonders for the bike’s previously oddball looks.

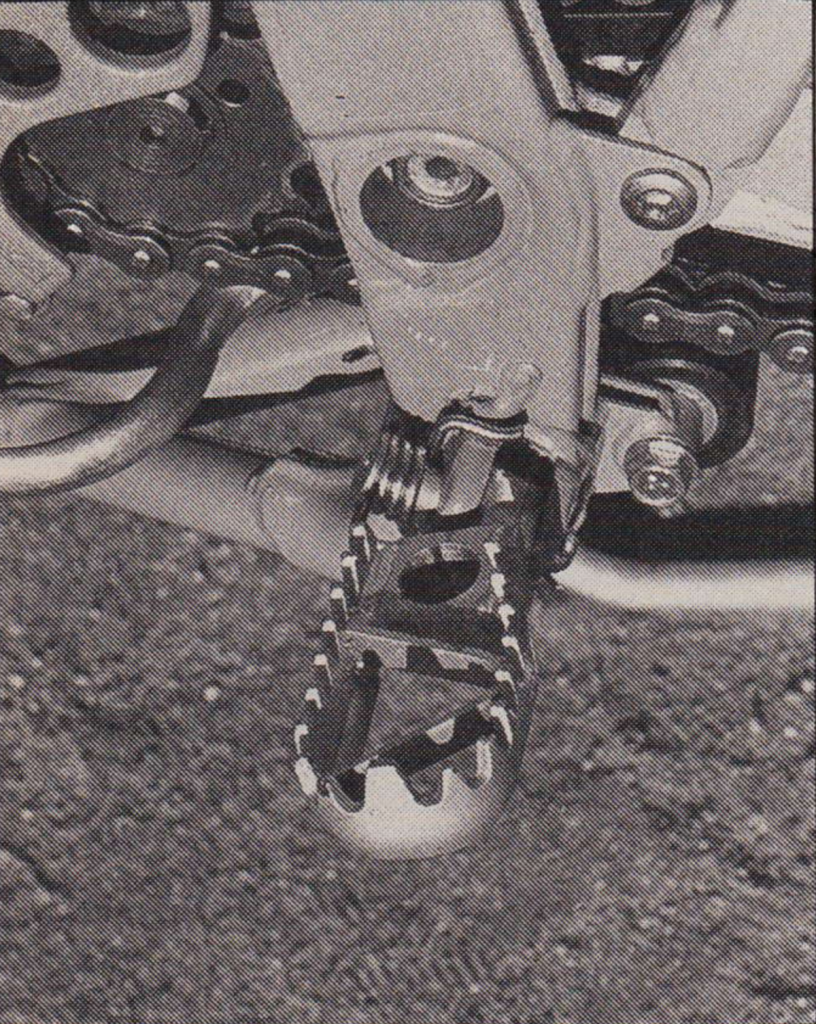

Ankle savers: Maybe the most long-lasting of the 1990 KX’s innovations was the introduction of these ultra-wide platform pegs to motocross. Photo Credit: MXA

Ankle savers: Maybe the most long-lasting of the 1990 KX’s innovations was the introduction of these ultra-wide platform pegs to motocross. Photo Credit: MXA

After the excellent 46mm conventional forks found on the ’89 KX, many riders were afraid the new model’s 41mm inverted KYBs would be a major step backward. Thankfully, those fears proved unfounded and the new KX turned out to have some of the best forks on the track in 1990. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

After the excellent 46mm conventional forks found on the ’89 KX, many riders were afraid the new model’s 41mm inverted KYBs would be a major step backward. Thankfully, those fears proved unfounded and the new KX turned out to have some of the best forks on the track in 1990. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

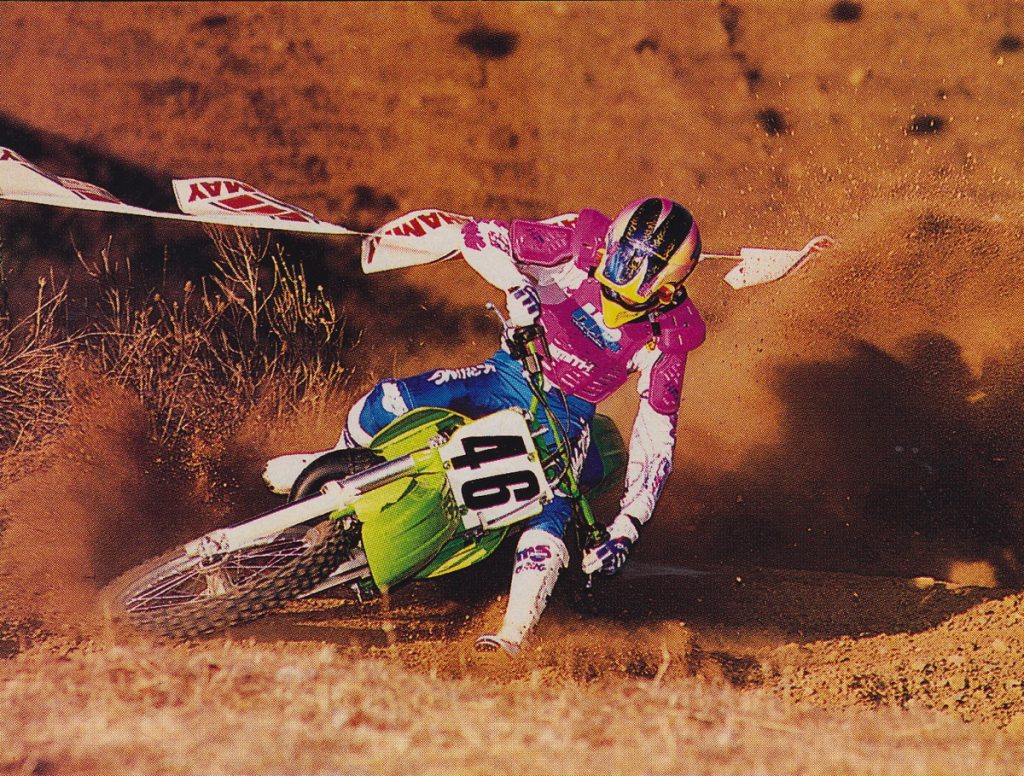

Predictably, with all of these changes, the new KX125 offered a completely different feel from previous years. Even though the engineers had gone all-out to lower the bike’s center of gravity, the high steering head and wide frame spars made the bike feel taller than any other 125. In spite of this top-heavy feel, however, the new KX proved an able cornering partner. With its short wheelbase (shortest of the Big Four 125s) and steep steering angle, the KX could cut and thrust far better than in the past, but it also felt far twitchier than older KX125s. The new frame and inverted forks made the steering feel more precise than ever before, but for riders jumping off of the other brands, the bike could seem a bit odd at first. With its tall seat and wide frame, the KX felt far more like a 250 than a 125 and many riders had a tough time adjusting to its Paul Bunyan proportions. At 202 pounds, the KX was also about 10 pounds heavier than any other 125 in the class, and on the track, you could feel those extra pounds.

With its steep geometry and short wheelbase, the new KX125 proved a more able cornering partner than past Kawasaki 125s. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With its steep geometry and short wheelbase, the new KX125 proved a more able cornering partner than past Kawasaki 125s. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the radical new chassis was somewhat of an acquired taste, the new motor was far less polarizing. In 1989, the KX125 had been the most boring bike in the class. It was slow, listless and blah. There was a long pull, but no hit and very little drama. Kind riders called it a “lap-time” motor; less charitable racers called it a turd.

Like the front, the rear of the new KX was well-sorted and in the ballpark for the majority of 125-sized pilots. In stock condition, the Kawasaki provided the best overall suspension package in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Like the front, the rear of the new KX was well-sorted and in the ballpark for the majority of 125-sized pilots. In stock condition, the Kawasaki provided the best overall suspension package in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1990, all that turd talk was finally in the rear-view mirror. The new bike ash-canned the old motor’s long, drawn-out powerband and traded it in for a massive dose of braaapppp! Off the line, it was softer than 1989, but once on the pipe, it was all fire and fury. The new motor exploded in the midrange and barked at the moon as it pulled into an ear-splitting top-end hook. Like the similarly-powered Honda, the new KX required skill to make the most of its powerband. Novices were apt to find its peaky power frustrating, but pros and fast intermediates found its prodigious hit and top-end pull intoxicating.

This unique bolt-on top shock mount made servicing easier, but proved prone to cracking under hard use. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

This unique bolt-on top shock mount made servicing easier, but proved prone to cracking under hard use. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

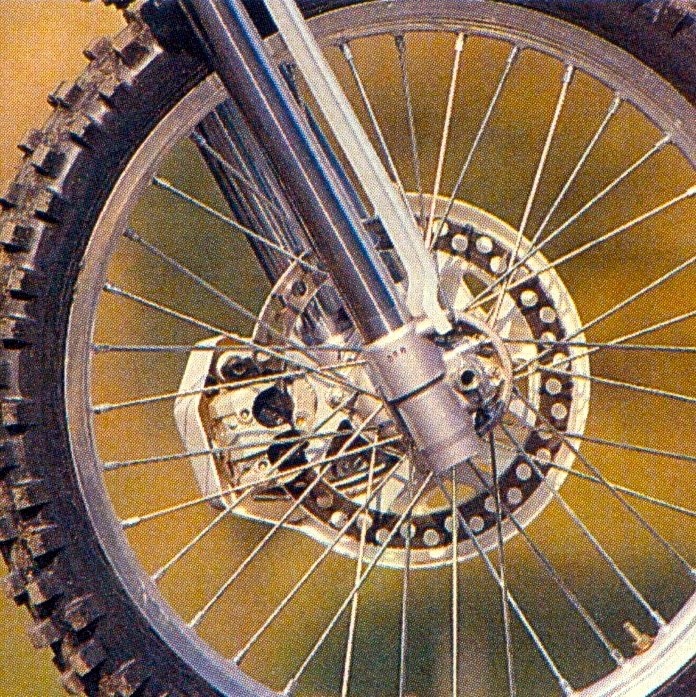

Braking power on the new KX was very good, but both the front and rear units required constant bleeding to maintain proper performance. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

Braking power on the new KX was very good, but both the front and rear units required constant bleeding to maintain proper performance. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

On the suspension front, the new KX proved just as excellent as its mellow predecessor. The new 41mm Kayaba inverted cartridge forks were applauded by all for their comfort and control. With 12.2 inches of travel and adjustments for compression and rebound, riders of nearly every skill level could find settings that worked to their likening.

It took a talented rider like MXA’s Willy Musgrave to get the most out of the 1990 KX125’s potent, but pipey power package. Photo Credit: Mike Kroger

It took a talented rider like MXA’s Willy Musgrave to get the most out of the 1990 KX125’s potent, but pipey power package. Photo Credit: Mike Kroger

Out back, the Kayaba shock and revised Uni-Trak offered similarly excellent performance. Like the forks, there were adjustments for compression and rebound, with a whopping 13 inches (most in the class) of plush travel. Both the spring rates and valving were well-sorted and certainly within the range of the bike’s target audience. Really fast guys may have wanted a re-valve and spring swap at both ends, but for most mortals, the stock settings were excellent.

In June, Factory Kawasaki’s Jeff Emig collected $10,000 for taking the new KX to victory in the season-ending East-West 125 Supercross shootout. Photo Credit: MXA

In June, Factory Kawasaki’s Jeff Emig collected $10,000 for taking the new KX to victory in the season-ending East-West 125 Supercross shootout. Photo Credit: MXA

On the details front, the new KX proved a mix of some really great ideas, and a few disappointing missteps. Innovations like its massive (for the time) footpegs and perimeter frame started trends that continue to this day, but other items like its unique bolt-on shock tower proved more problematic. The mounting bolts had to be watched like a hawk and cracked mounts proved all but inevitable. In truth, nearly all the bolts on the bike were junk, with the strip-o-matic riv-nuts on the sub-frame proving the worst. General plastic quality was better than previous KXs, but the gas cap continued to crack incessantly and douse your man berries in premix. If the gas cap held together, then the stock pipe was sure to blow out at the seam and spritz your boots with black exhaust spluge. Those massive footpegs also drooped after a few months of use and liked to eject their return springs on a regular basis.

In 1990, Kawasaki introduced an all-new 125 that pushed the envelope of design and style. It was fast, well-suspended and incredibly trick, but not necessarily the best 125 for every rider. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1990, Kawasaki introduced an all-new 125 that pushed the envelope of design and style. It was fast, well-suspended and incredibly trick, but not necessarily the best 125 for every rider. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Overall, the new Kawasaki KX125 proved the most polarizing 125 of 1990. No one could dispute its trick factor, but many riders could not come to grips with its demanding power and unique feel. It was taller, wider and heavier than any other bike in the class, with a skyscraper seat height and short wheelbase. This made it top-heavy in the corners and twitchy on the straights. Its excellent suspension, roomy chassis and barky motor made many big and fast guys happy, but for a lot of riders, it was too big, too fat and too demanding. Bold in design, innovative in execution and uniquely beautiful, the 1990 KX125 was not a perfect bike, but it was an early glimpse at the future of motocross design in the new millennium.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com