For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new CR125R for 2000.

All-new from the ground up, Honda’s CR125R looked to reclaim lost glory in 2000. Photo Credit: Honda

All-new from the ground up, Honda’s CR125R looked to reclaim lost glory in 2000. Photo Credit: Honda

From the mid-eighties through the mid-nineties, few machines in motocross were as successful as Honda’s eighth-liter racers. Great looking, impeccably built, and blessed with the most power in the class, the CR125R was the gold standard of the tiddler division for a decade. In 1996, that run of horsepower dominance finally ended with the introduction of Yamaha’s all-new YZ125. Long the whipping boy of the 125 class, the new YZ stole the Honda’s thunder with a broad, fast, and wickedly effective spread of ponies. The Honda still held the advantage at the stratospheric end of the power curve, but below those ear-splitting levels, the new blue Why-Zed was king.

The all-new frame on the CR125R was slimmer, more compact, and less rigid for 2000. Photo Credit: Honda

The all-new frame on the CR125R was slimmer, more compact, and less rigid for 2000. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1997, Honda chose to stand pat in the 125 division, while pouring all of their resources into an all-new alloy-framed CR250R. This bike, while beautiful to look at and incredibly trick, proved controversial on the track. Its motor continued to be the class standard, but the new aluminum chassis provided a harsh and unforgiving ride that few riders appreciated.

Both the CR250R and CR125R featured new looks for 2000 with redesigned bodywork and a switch to a less deep shade of red Honda called “Explosion Red.” Photo Credit: Honda

Both the CR250R and CR125R featured new looks for 2000 with redesigned bodywork and a switch to a less deep shade of red Honda called “Explosion Red.” Photo Credit: Honda

For 1998, Honda pulled out all the stops and introduced their first all-new CR125R in five years. The redesigned machine adopted a scaled-down version of the CR250R’s alloy chassis and mated it to a updated 125cc mill. The new motor retained the HPP (Honda Power Port) system it had employed since 1990 and paired it with a new five-speed transmission. According Honda, the deletion of the sixth gear in the CR’s tranny was aimed at bolstering reliability. By offering one less cog, the remaining five gears could be enlarged and beefed up without increasing overall weight. New bodywork finished off the package and made the 125 look just like its controversial big brother.

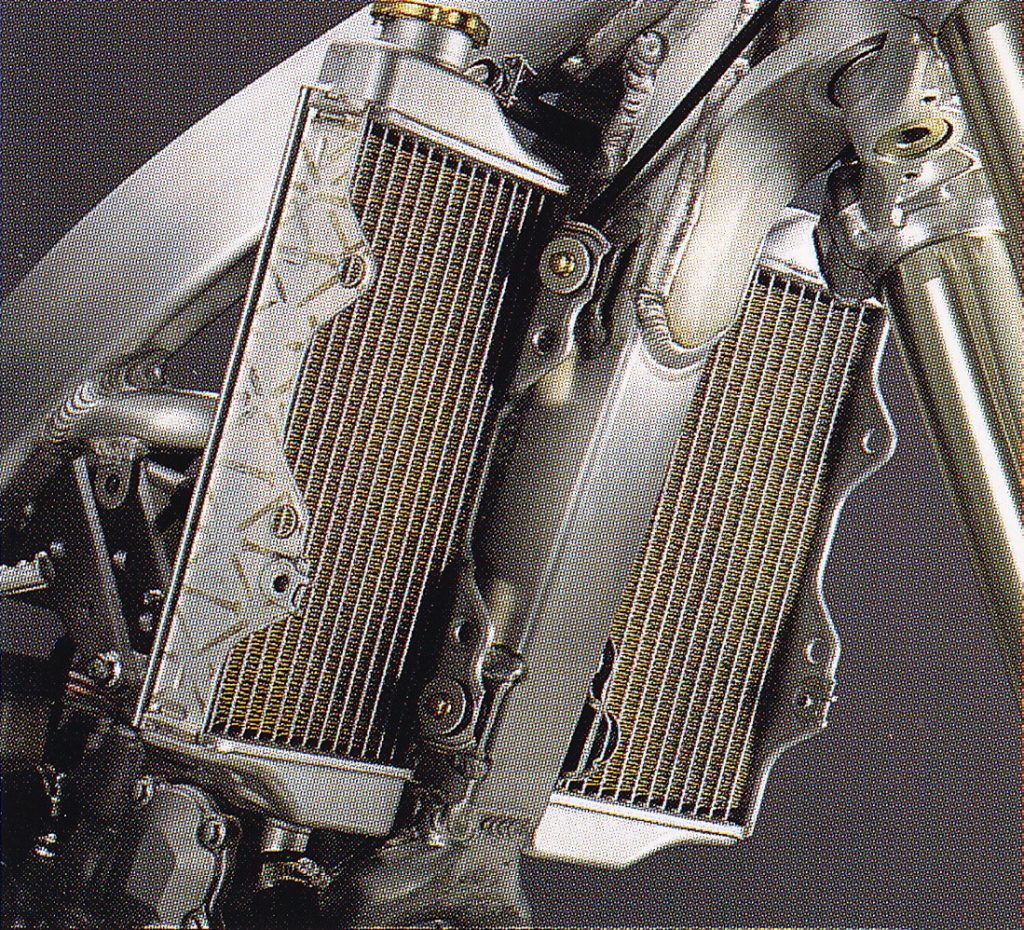

A switch back to a single downtube for 2000 meant the large single radiator of ’98-’99 needed to be retired in favor of a more conventional dual-radiator configuration. Photo Credit: Honda

A switch back to a single downtube for 2000 meant the large single radiator of ’98-’99 needed to be retired in favor of a more conventional dual-radiator configuration. Photo Credit: Honda

On the track, this new-look CR125R turned out to be a massive step backward in performance. Instead of overtaking the YZ, the CR was shuffled to the back of the pack with a peaky motor, dead-feeling chassis and hand-numbing vibration. Midrange power was good, but the previous CR’s awesome top-end was DOA. Something about the new frame, airbox, or motor design robbed the Honda of its most defining quality and left riders scratching their heads in disappointment and disbelief.

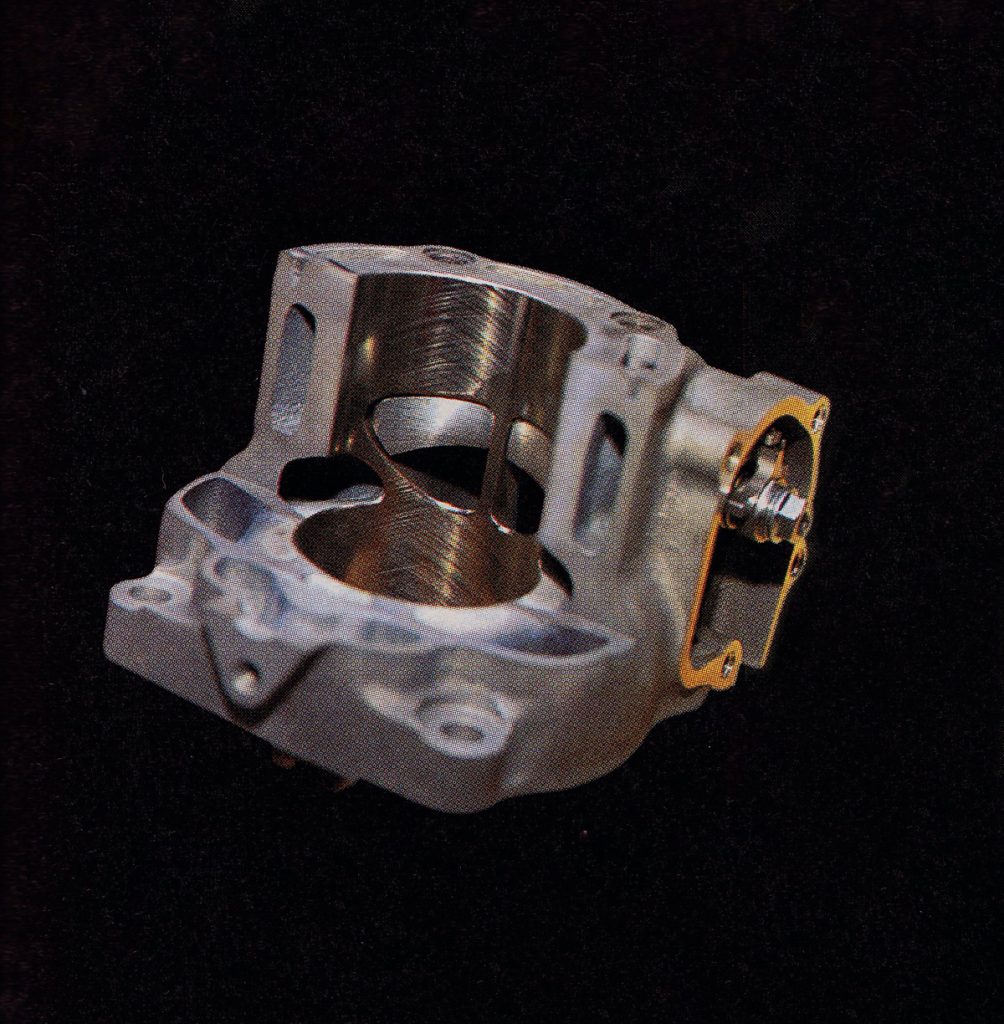

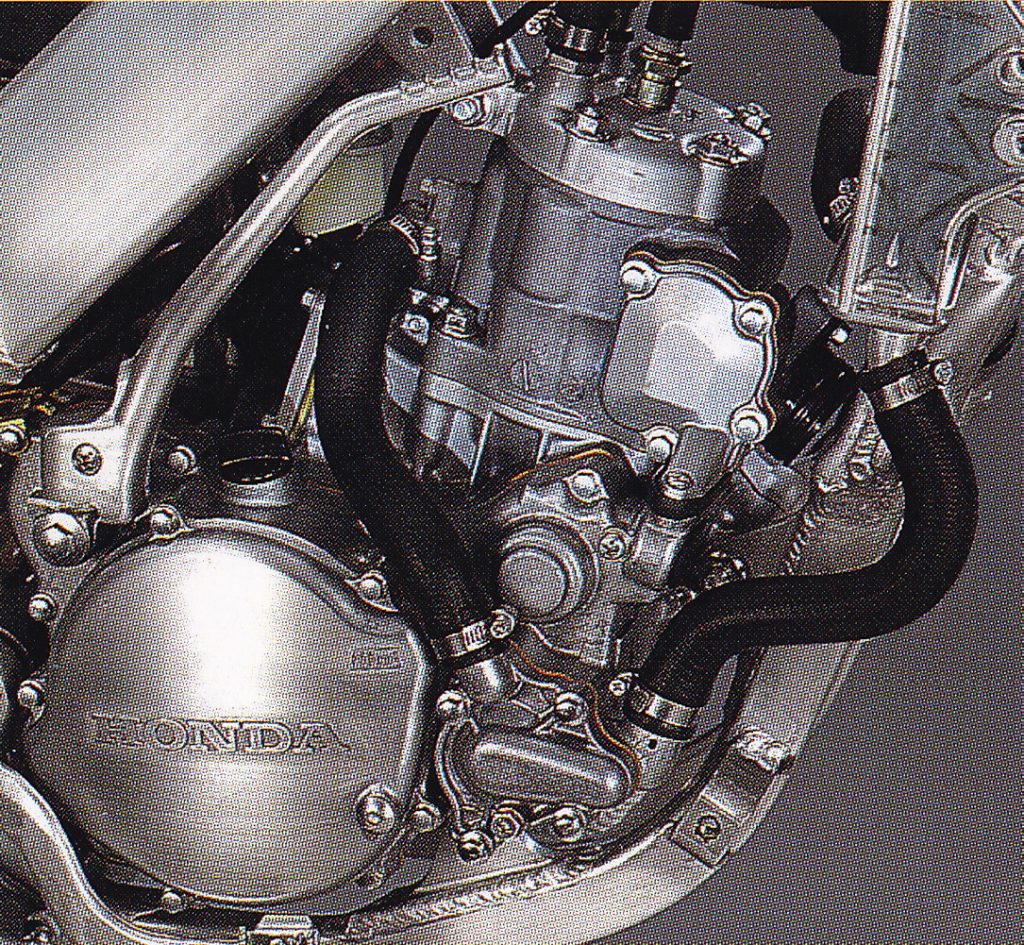

An all-new cylinder design for 2000 replaced the HPP in use since 1990 with a new NSR road-racing-inspired flapper valve Honda coined the “Revolutionary Control” (RC) valve, Photo Credit: Scott Hoffman

An all-new cylinder design for 2000 replaced the HPP in use since 1990 with a new NSR road-racing-inspired flapper valve Honda coined the “Revolutionary Control” (RC) valve, Photo Credit: Scott Hoffman

After mild updates and another drubbing for 1999, it was back to the drawing board for Honda and their 125 program in 2000. An all-new machine was spec’d out that maintained the alloy chassis, but nipped, tucked and trimmed it in significant ways. In addition to the new frame, the bike featured restyled bodywork, updated suspension, and the most significant update of Honda’s 125 motor in a decade. Reimagined from the ground up, this new CR125R promised to bring glory back to the Big Red Machine after several years in the wilderness of 125 mediocrity.

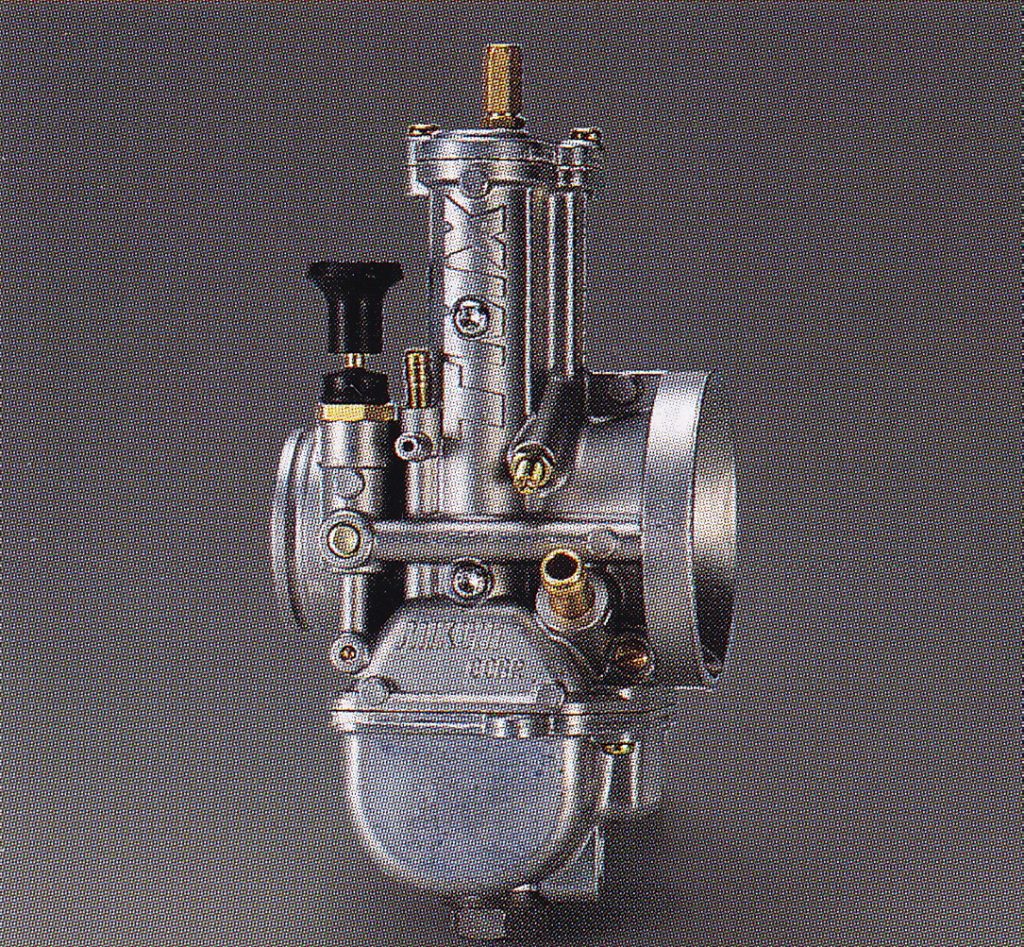

After thirty years of using Keihin carburetors on their CRs (Honda is a nearly 50% owner of Keihin), Honda made the bold choice to switch to Mikuni in 2000. Photo Credit: Honda

After thirty years of using Keihin carburetors on their CRs (Honda is a nearly 50% owner of Keihin), Honda made the bold choice to switch to Mikuni in 2000. Photo Credit: Honda

When redesigning their CR125R for the new millennium, the Honda engineers knew that they were going to have to coax some more ponies out of their eighth-liter racer if it was going to have any chance of unseating Yamaha’s omnipotent YZ125. Broad, torquey, and blisteringly fast, the YZ125s of the late nineties and early two-thousands romped on the competition with powerbands that made the other machines in the class feel like minis. In a class where the motor was everything, that was a huge advantage.

In edition to offering a narrower profile, the new frame featured a steeper head angle for improved turning. Photo Credit: Honda

In edition to offering a narrower profile, the new frame featured a steeper head angle for improved turning. Photo Credit: Honda

In order to give the new CR125R a fighting chance, Honda decided to finally retire their successful but aging HPP system and dial up an all-new power valve design. This time, they went to the road race department for inspiration and came up with a new design based off of their NSR500 GP racer. This new design replaced the sliding guillotine valves of the HPP with a rotary-flap design that was lighter, more compact, and simpler to service. Dubbed “Revolutionary Control” (RC) valve, this new design was said to offer more precise control and a smoother transition when opening and closing. Internally, the new motor maintained its case-reed configuration and continued to offer only five speeds in the transmission. Because the motor was said to offer more torque than previous designs, Honda added an additional plate (for a total of eight) to the clutch for durability.

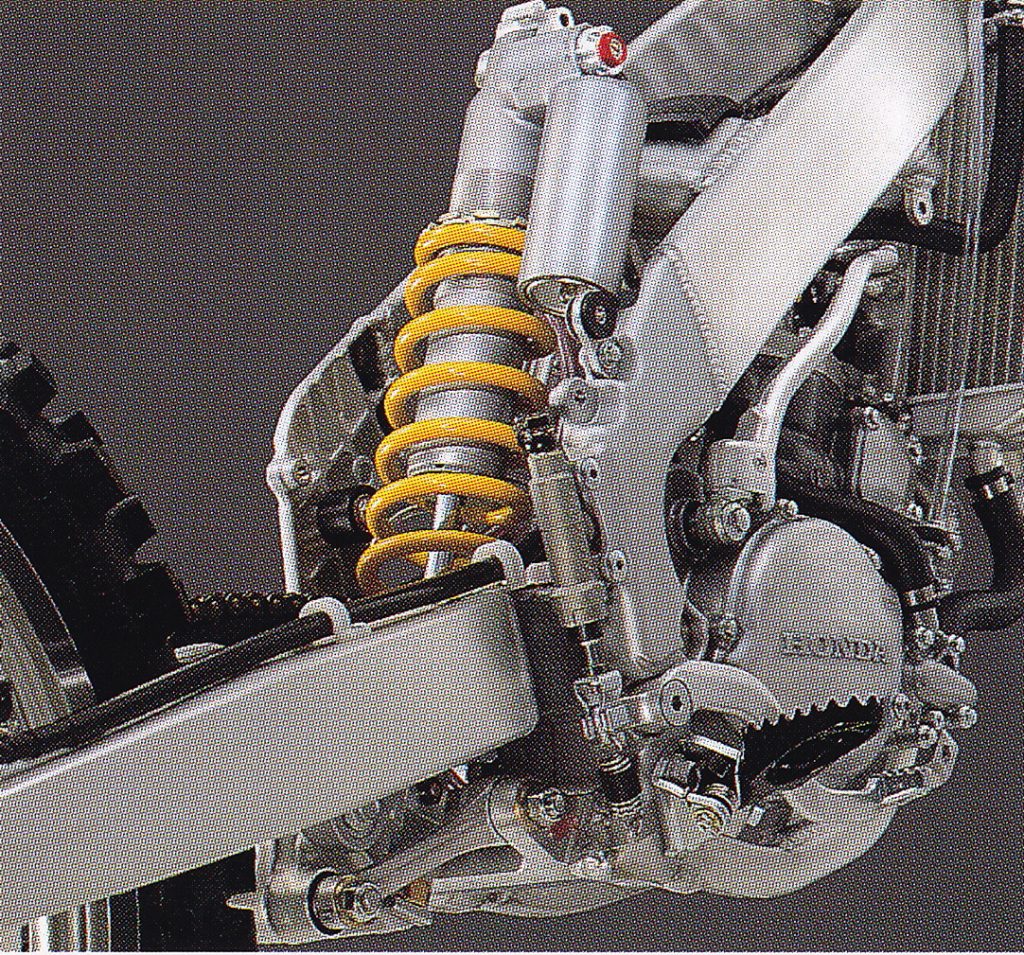

A redesigned linkage and repositioned shock improved ground clearance and centralized mass for 2000. Photo: Credit Honda

A redesigned linkage and repositioned shock improved ground clearance and centralized mass for 2000. Photo: Credit Honda

On the intake side, the new bike featured a totally redesigned airbox and air boot. This had long been suspected to be one of the choke-points in the old motor and one of the reasons for the 1998’s loss of power. This new design was 35% larger and freer-breathing in hopes of finding some of the red bike’s lost top end. In addition to the new airbox, a new carburetor was spec’d that replaced Honda’s long-time partner Keihin with a new 36mm Mikuni TMX mixer. According to Honda, this was done to improve throttle response on the previously boggy motor. Finishing off the motor package was an all-new expansion chamber and silencer tuned to the characteristics of the new mill.

After the lackluster reviews for Honda’s first-generation aluminum frame, the engineers went to great lengths to make certain the second-generation chassis would offer a better feel and improved ergonomics. Photo Credit: Honda

After the lackluster reviews for Honda’s first-generation aluminum frame, the engineers went to great lengths to make certain the second-generation chassis would offer a better feel and improved ergonomics. Photo Credit: Honda

On the chassis side of things, Honda was just as thorough with its redesign as it had been with the motor. In 1997, when Honda had first introduced the alloy frame on its CR250R, the press and public had gone gaga over its spacy appearance and “trickness” quotient. It literally looked unlike anything else ever offered for sale in the motocross arena and captured massive sales on the basis of Honda’s reputation and an expectation that it just had to be good. Once in consumer’s hands, however, the new bikes proved a harder sell. When designing this first-gen chassis, Honda had prioritized durability over all else and the result had been an overly stiff and unforgiving feel.

The new motor for 2000 maintained the controversial five-speed transmission of the ’98-’99 model and added an additional plate to the clutch (for a total of eight) for improved durability. Photo Credit: Honda

The new motor for 2000 maintained the controversial five-speed transmission of the ’98-’99 model and added an additional plate to the clutch (for a total of eight) for improved durability. Photo Credit: Honda

For 2000, Honda looked to remedy this complaint by completely redesigning the alloy chassis on the CR125R. The new frame aimed to increase comfort by both downsizing the dimensions of the frame and dialing in some much-needed flex. To accomplish this, the engineers reduced the height of the main frame spars by 10mm and switched from extrusion to forging for the head tube. The double down tubes of ’98-’99 were retired in favor of a single downtube for 2000 and the frame spars were narrowed 15% to give the bike a slimmer feel.

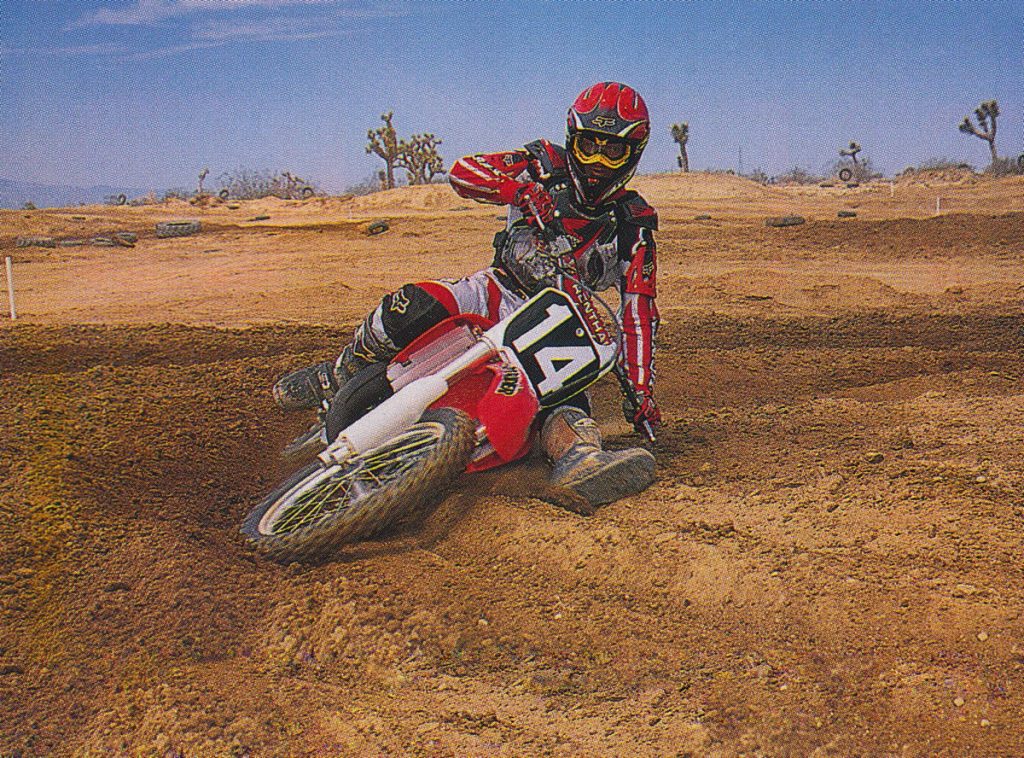

On the track, the new CR125R handled worlds better than ’99. The new chassis ditched the dead feel and front-end push of the old design and replaced it with a light feel and precise manners. PulpMX’s ace tester Kris Keefer demonstrates. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

On the track, the new CR125R handled worlds better than ’99. The new chassis ditched the dead feel and front-end push of the old design and replaced it with a light feel and precise manners. PulpMX’s ace tester Kris Keefer demonstrates. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

To improve handling, the steering head angle was steepened by .65 degrees and the shock was repositioned to sit 20mm farther forward. The wheelbase was also increased slightly (.4 inches) and the main frame spars were repositioned 30mm lower to improve ergonomics and centralize mass. All told, these changes added up to a slimmer feel and an impressive 25% increase in torsional flex. Normally an increase in flex was not the sort of thing a manufacturer would brag about, but after the poor reception the first-generation chassis received, this increase in flex was a welcome change.

The new 47mm Kayaba SASS forks on the CR125R offered a firm ride and superior control. While not as plush as some of the competition, they offered the best performance for aggressive riders. Photo Credit: Honda

The new 47mm Kayaba SASS forks on the CR125R offered a firm ride and superior control. While not as plush as some of the competition, they offered the best performance for aggressive riders. Photo Credit: Honda

On the suspension end of things, the 2000 CR125R received all-new components both front and rear. At the front, new 46mm (some tests and one of the Honda brochures I used for research listed these as 47mm but others contradict this and say 46mm) Kayaba SASS (Speed Activated Spring System) forks promised plusher action, improved bottoming feel, and increased steering precision. This new fork, often referred to as a “bladder” design, used a small rubber sleeve over the cartridge system to separate the fork oil from the oil in the cartridge and minimize aeration of the fluid. This was basically a simpler and lower-cost version of what Showa was offering with their Twin-Chamber design.

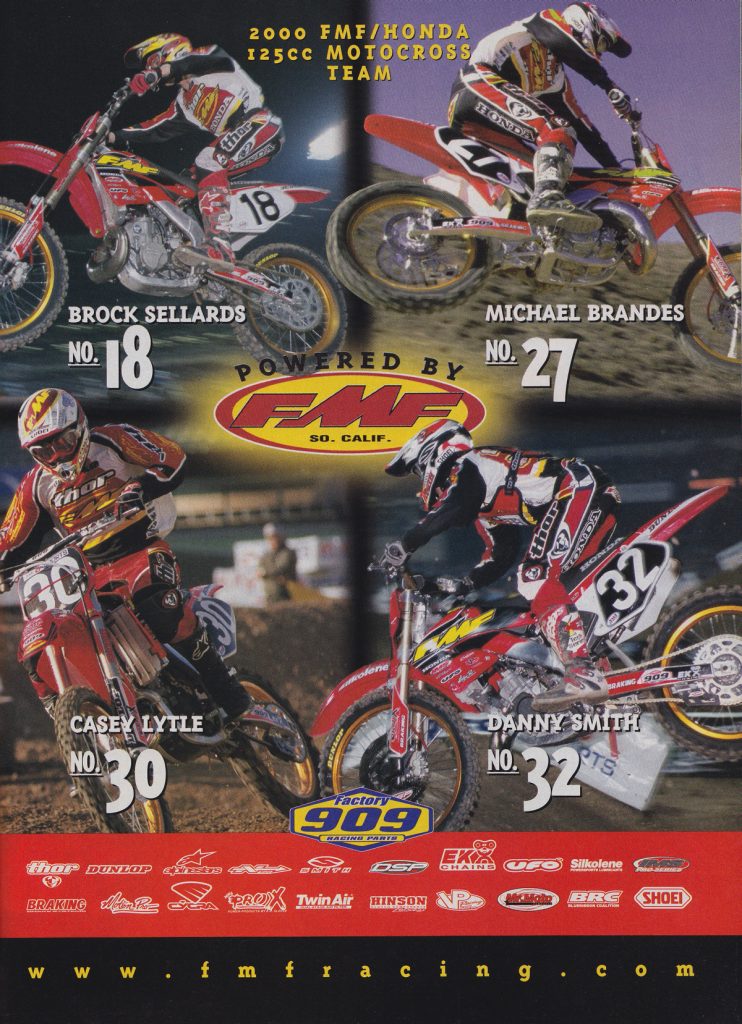

In 1999, Honda had moved its 125 effort out of the factory truck and into to the hands of longtime Pro Circuit rival FMF. At the end of the 2000 season, FMF would fold its 125 effort after only two years on the circuit.

In 1999, Honda had moved its 125 effort out of the factory truck and into to the hands of longtime Pro Circuit rival FMF. At the end of the 2000 season, FMF would fold its 125 effort after only two years on the circuit.

Out back, the CR once again employed KYB for the damper duties and paired a new hi-low adjuster shock with a redesigned linkage and beefed-up swingarm. The new linkage was lighter overall and featured a new curve that was softer initially and firmer as it neared full travel. The redesigned swingarm featured a new dual-taper design, large cast cross-member, and a 5mm larger rear axle. These combined to give the ’00 CR125R rear end a 25% increase in torsional flex resistance over ’99.

In 2000, FMF’s Brock Sellards was the top-finishing Honda rider in the 125 class. At Troy in July, Brock would take his CR125R to a double-moto win on is way to fourth overall in the 125 National championship. Photo Credit: Motocross Journal

In 2000, FMF’s Brock Sellards was the top-finishing Honda rider in the 125 class. At Troy in July, Brock would take his CR125R to a double-moto win on is way to fourth overall in the 125 National championship. Photo Credit: Motocross Journal

Finishing off the ’00 CR125R package was all-new bodywork that freshened the looks and improved the ergonomics over ’99. The new “Explosion Red” plastic came in a slightly less deep shade of red and featured new lines and freshened-up graphics. The new seat was slightly thicker for ’00 and incorporated a softer foam for improved butt comfort. To further aid comfort, new clamps were bolted on that offered both reversible offset mounts and rubber grommets. This was done to both allow for more customization and reduce some of the annoying vibration that had plagued the previous alloy-framed CRs.

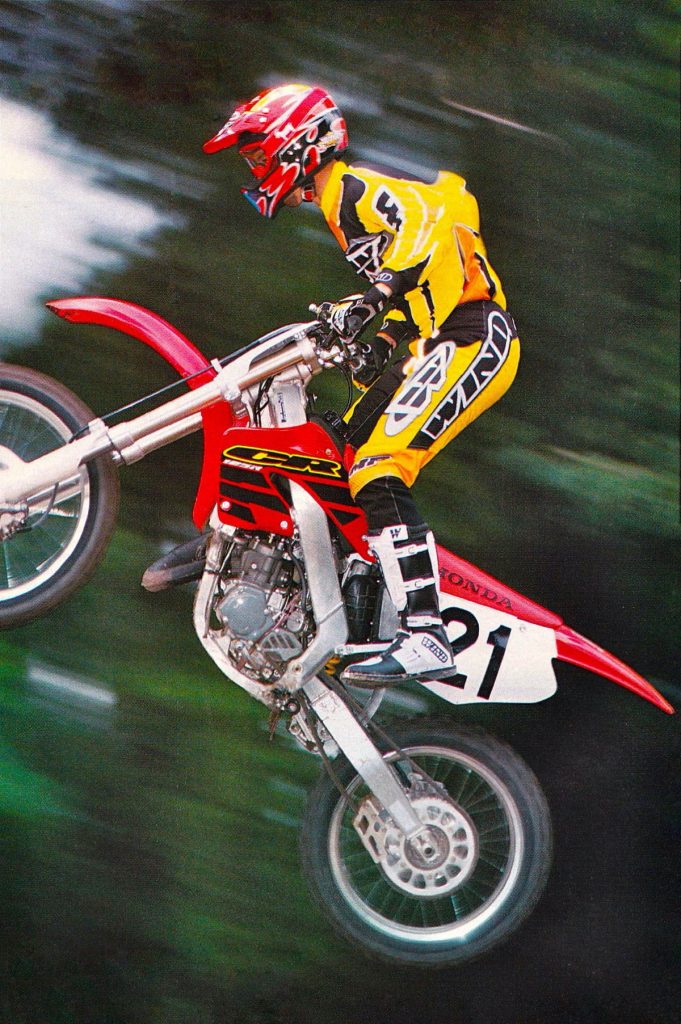

In 2000, by far the highest profile rider on the new CR125R was two-time 125 National Motocross champion Steve Lamson. After a sub-par year on the Chaparral Yamaha team, Lamson was back on Hondas with support from Works Connection and Troy Lee Designs. Early on in the year, it looked like a return to form for the champ as he won Hangtown and lead the 125 series. Eventually, however, his championship hopes would come back to Earth and the long-time veteran would end the series in fifth overall. Photo Credit: MX Racer

In 2000, by far the highest profile rider on the new CR125R was two-time 125 National Motocross champion Steve Lamson. After a sub-par year on the Chaparral Yamaha team, Lamson was back on Hondas with support from Works Connection and Troy Lee Designs. Early on in the year, it looked like a return to form for the champ as he won Hangtown and lead the 125 series. Eventually, however, his championship hopes would come back to Earth and the long-time veteran would end the series in fifth overall. Photo Credit: MX Racer

On the track, the 2000 CR125R turned out to be a major improvement over the bike it replaced. The new motor continued to be devoid of any low-end torque, but midrange performance was strong. Top end power was improved over ’99 but still not the CR’s strong suite. It continued to do its best work in the midrange and preferred to be short-shifted rather than revved out. Out of corners, a fair amount of clutch abuse was necessary to get past the lethargic low end, but once it was on the pipe, the CR at least was competitive. Thankfully, the new eight-plate clutch was up to this abuse, but the CR500-like pull it required was panned by those without the grip strength of Mike LaRocco.

The new RC-valve motor on the CR125R offered an improved midrange over ’99, but not much else. Low-end torque was non-existent and the top-end pull was only slightly improved over the year before. When it was on the pipe it was fast, but above or below this burst, it was painfully average. Photo Credit: Honda

The new RC-valve motor on the CR125R offered an improved midrange over ’99, but not much else. Low-end torque was non-existent and the top-end pull was only slightly improved over the year before. When it was on the pipe it was fast, but above or below this burst, it was painfully average. Photo Credit: Honda

Compared to the class-leading YZ125, the CR was less potent at every point on the curve. In the midrange, it came close to giving the blue machine a run for its money, but above or below its sweet spot, the YZ pulled away. In a fight against the KX or RM, the CR fared better and could hold its own. If you picked on a KTM 125SX, however, it was best to brush up on your blocking skills and learn to ride a wide bike, lest the potent Austrian leave you in its vapor trail.

With 32.1 horsepower on tap, the new CR125R motor sat dead center in the peak power sweepstakes. It was less potent than the broad YZ and rocket-fast KTM, but spritelier than the KX or RM. As long as you could keep it in the sweet spot of its midrange-focused powerband, the CR was competitively fast. Photo Credit: Honda

With 32.1 horsepower on tap, the new CR125R motor sat dead center in the peak power sweepstakes. It was less potent than the broad YZ and rocket-fast KTM, but spritelier than the KX or RM. As long as you could keep it in the sweet spot of its midrange-focused powerband, the CR was competitively fast. Photo Credit: Honda

On the handling front, the new CR was once again majorly upgraded for 2000. The new frame felt much thinner through the middle and much more responsive on the track. The “dead” feel of the old overbuilt chassis was greatly lessened and the new bike steered, tracked and felt like a 125 should. It was still far stiffer than any other 125, but it no longer thudded in the whoops and pushed the front end in the corners. With its more resilient chassis, plusher seat and rubber-mounted bars, the new bike was far less tiring to ride than the 1999 as well. Vibration was still more noticeable than on any of the steel-framed bikes, but at least it no longer numbed your digits before the end of the first lap.

The KYB shock on the new CR offered a firm and well-controlled ride that was favored by fast and slow guys alike. Photo Credit: Honda

The KYB shock on the new CR offered a firm and well-controlled ride that was favored by fast and slow guys alike. Photo Credit: Honda

On the suspension end of things, the new CR125R offered one of the best packages on the track in 2000. The new Kayaba SASS forks were set up well for heavier/faster riders and provided a well-damped and controlled ride. At low speeds and on chop, they were sufficiently plush, and at high speeds they maintained excellent damping performance. Even on big hits, bottoming never became a problem and the bike offered the best combination of firmness and comfort in the class.

While the new RC-valve cylinder offered several benefits over the more complicated HPP design, several riders and teams were not yet sold on its benefits. This Plano Honda of Scott Sheak for example used a modified 1995 CR125R cylinder because of its superior top-end power. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the new RC-valve cylinder offered several benefits over the more complicated HPP design, several riders and teams were not yet sold on its benefits. This Plano Honda of Scott Sheak for example used a modified 1995 CR125R cylinder because of its superior top-end power. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Out back, the CR’s KYB damper was equally praise-worthy. It offered 12.2 inches of travel with adjustments for high and low speed compression as well as rebound damping. As with the forks, the shock was set up on the stiff side for slow or ultra-light riders, but for hard core motocross, it was spot on. Big woops and mega leaps were no problem on the CR and the harder you charged, the better it performed. Some riders preferred the KX’s plusher feel, but fast guys appreciated the Honda’s better bottoming resistance and superior high-speed performance.

With its excellent suspension big air was no problem on the 2000 CR125R. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With its excellent suspension big air was no problem on the 2000 CR125R. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the detailing side of things, the new CR125R was an improvement in most areas over its predecessor. The new frame was thinner through the middle and more forgiving in the rough. Most riders loved the new thicker seat, slimmer bodywork and reversible, rubber-mounted bar clamps. While slimmer overall, the CR did continue to be wider at the pegs than any of the 125 competition. Not everyone was bothered by this, but some riders commented on it when switching from brand to brand.

In 2000, these were still the best brakes in motocross. Photo Credit: Honda

In 2000, these were still the best brakes in motocross. Photo Credit: Honda

On the awesome side were the Honda’s brakes (tons of power, excellent feel and minimal maintenance), grips (no need to upgrade), levers (tough, comfortable and malleable), and fasteners (no junk here). With its alloy frame, high-quality materials and impeccable build quality, the CR also looked and felt fresh long after the point where the KX, RM and YZ had begun to show their age. As long as you kept the filter clean and changed the top-end at semi-regular intervals, the CR was as bulletproof as a 125 could be.

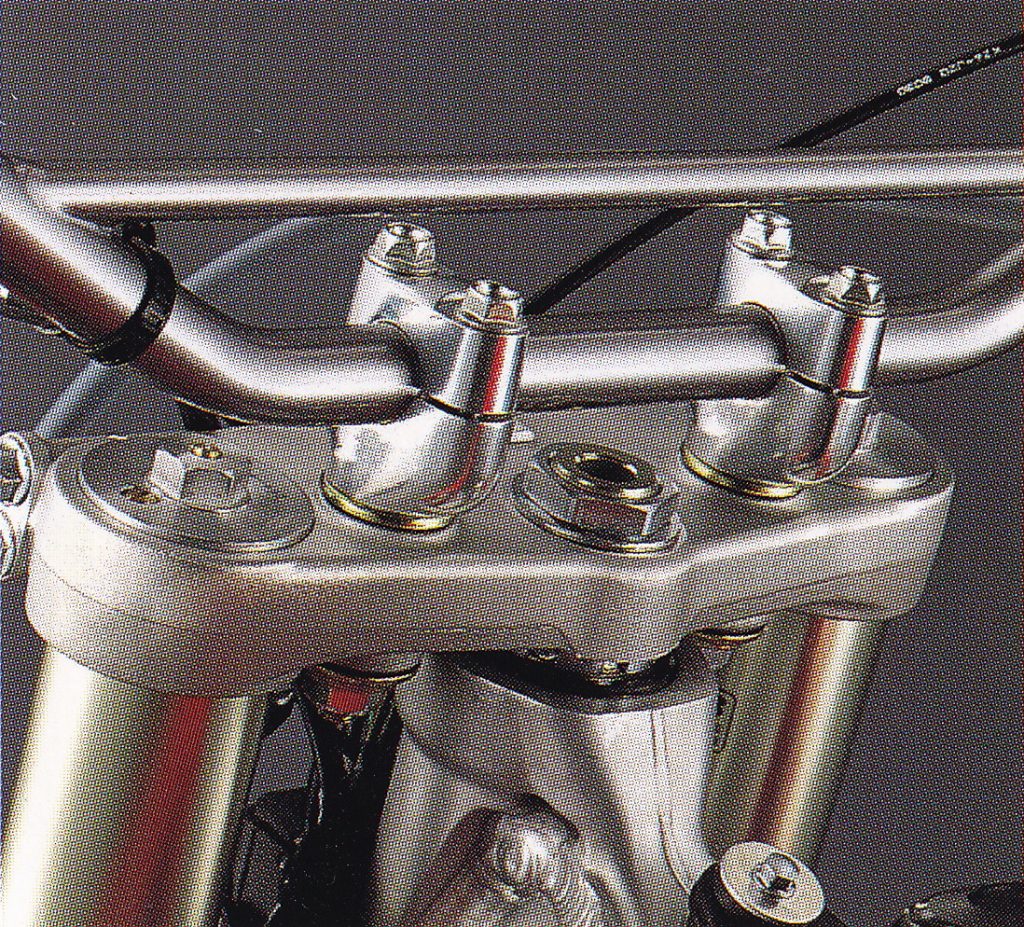

New clamps for 2000 added rubber grommets and reversible mounts for improved comfort and adjustability. Photo Credit: Honda

New clamps for 2000 added rubber grommets and reversible mounts for improved comfort and adjustability. Photo Credit: Honda

In the minus column were the CR’s stock chain (hot butter was tougher), clutch pull (He-Manly), vibration (putting the buzz in buzz-bombs since 1998), and lackluster low-end (start working on those clutch-hand exercises). With a swap in gearing, the whaaa-whaaas down low got better, but the CR was never going to bark out of a turn like a YZ125.

New and improved in most every way, the 2000 CR125R was competitive, but no longer the superstar of the 125 class it had been a decade before. Photo Credit: Honda

New and improved in most every way, the 2000 CR125R was competitive, but no longer the superstar of the 125 class it had been a decade before. Photo Credit: Honda

In 2000, Honda reinvented its CR125R in hopes of recapturing its lost mojo. The new machine turned out to be major step forward in many ways, but not in the one that counted most. Without a world-beating motor to back up their excellent chassis, the CR125Rs of 2000 and beyond were destined to be liked, but not loved in the way their predecessors had been.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram – @TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com