For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s first legitimate 250 Enduro machine, the 1976 MR250 Elsinore.

In 1976, Honda introduced Japan’s first serious off-road Enduro racer. The new MR250 brought the name of the Elsinore and much of its motocross sibling’s performance into the world of trees and timekeeping. Photo Credit: Honda

Today, as in the seventies, the hard-core off-road market remains largely the playground of the European marques. Once dominated by the likes of Montesa, Ossa, Maico, and Bultaco, today’s off-road landscape is ruled by KTM, Husqvarna, and Beta. The Europeans still build the largest variety of models and the most serious offerings. They build two-strokes and four-strokes, in every imaginable size and configuration. The Euros know that there is a huge market for off-road machines that are as comfortable in the woods as they are on the track. Having a bike that can rip through the trees on Saturday and still be able to spin a few laps at Muddy Spuds Raceway on Sunday is a huge draw when only one machine will fit in the budget.

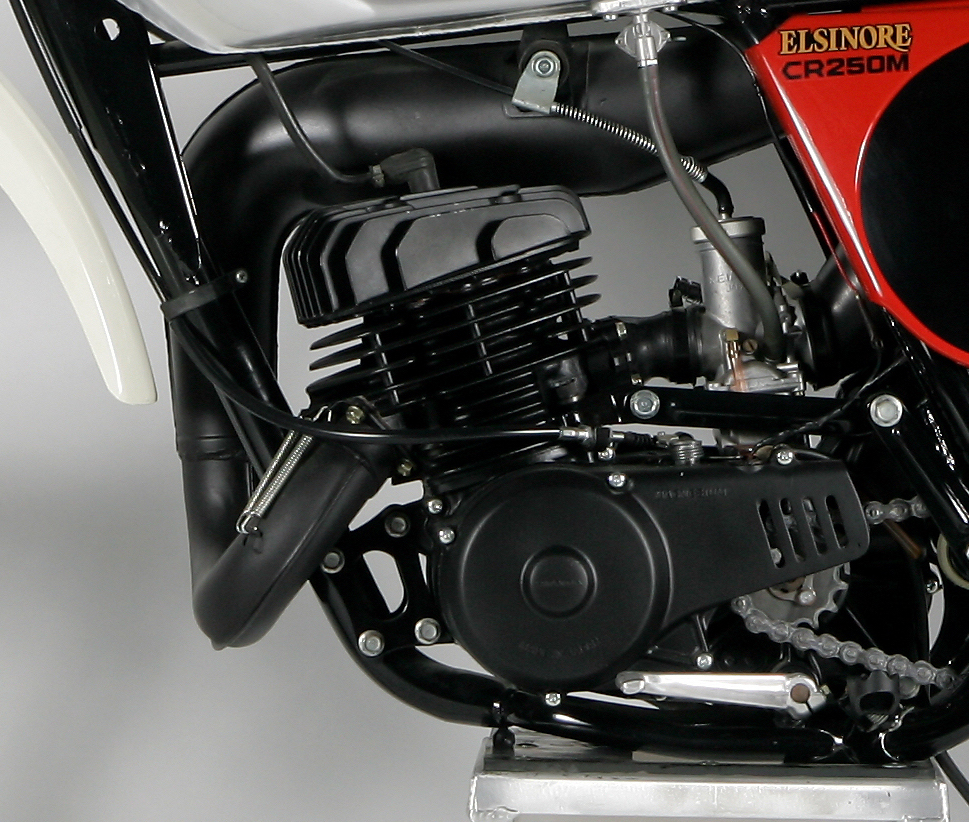

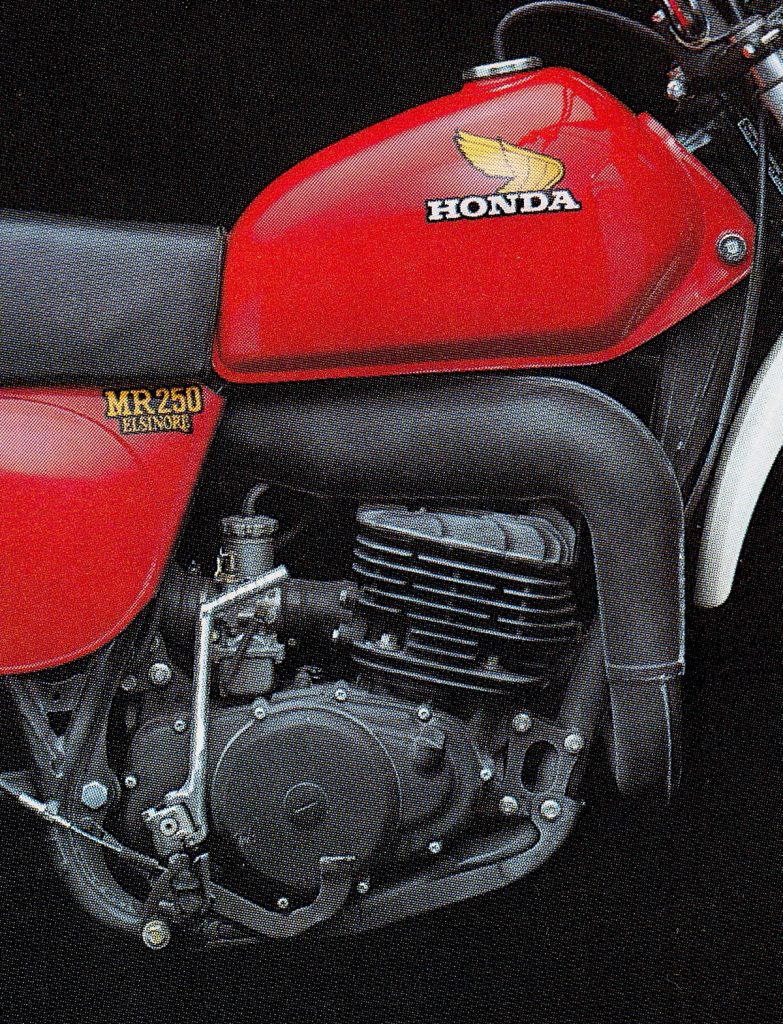

The new MR250 shared most of its motor design with the previous year’s CR250M power plant. The bore, stroke, pipe, and cases were identical and parts could be easily swapped between the two. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Over the years, the Japanese have taken a few stabs at this do-it-all approach, but most have been compromised in one way or another. Most of the time, the Japanese manufacturer’s desire to err on the side of comfort has led to bikes that were 30% hot and 70% not. The XRs, PEs, ITs, and KDXs could all be made into racers, but mega dollars and a do-it-yourself mentality were needed to get these glorified trail bikes up to speed with any stock off-roader from KTM or Husky. Even bikes like Suzuki’s excellent RMX250 came from the factory so plugged up that they could barely outrun a moped. In the case of the Japanese, bikes like the nineties Yamaha WR250 and current YZ250X and Honda CRF450RX are the exceptions, not the rule.

Like the motor, the chassis on the MR250 was a very close cousin to the one found on the ’75 CR250M. The two frames shared their dimensions and overall geometry but differed in the materials used for their construction (carbon steel for the MR and chromoly steel for the CR). Photo Credit: Honda

While it may seem like Honda has taken a long time to catch on to KTM’s magic formula, the truth is they actually had it all the way back when KTMs were still called Pentons here in the USA. Long before the first XR250 rolled off the assembly line, Honda had a legitimate no-compromise off-road racer in their stable. A bike every bit as serious as any modern KTM or Beta: the 1976 MR250 Elsinore.

Gas and Go: This Honda ad may have been a bit optimistic, but the MR250 Elsinore was the most race-ready 250 Enduro machine offered by the Japanese to this point.

In 1976, Honda was still very new to the serious off-road market. Only three years earlier, they had set the industry abuzz with their first two-stroke racer, the 1973 CR250M Elsinore. Named for the most prestigious US event of the time, the Elsinore GP in California, the all-new CR was a revelation in terms of affordability, quality, and out-of-the-crate performance. With only a few minor upgrades, it was capable of winning at any level and offered a far better ownership experience than anything else available at the time.

The MR also came in a 175 version based on the CR125M. Not quite as aggressive as the 250, the 175 lacked the Elsinore name and the bigger bike’s performance. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1976, Honda looked to take what they had learned with their motocross program and translate that into a machine that could dominate the woods just as the CR had done on the track. To do this, they decided the best course of action would be to take their proven CR250M Elsinore and graft on the bare minimum of off-road focused accouterments. This new machine would offer motocross performance with Enduro versatility.

The resulting MR250 featured a chassis design sourced directly from the previous year’s CR. The geometry and suspension components were virtually identical to what had been offered on the ’75 CR250M, but the MR had to make do with carbon steel for construction instead of the CR’s lighter and stronger chromoly steel. The motor was likewise based on the ’75 CR, with porting changes, a larger flywheel, wider-spaced gears, and a magneto ignition being the main differentiators. Externally, the two motors looked identical and even featured the same 34mm Keihin carburetor and works-style “up-pipe” exhaust. Visually, the main difference between the MR and its CR counterpart was the off-roader’s much larger 3.4-gallon gas tank, Enduro-required lighting, speedometer, and massive 86db silencer. Otherwise, the new MR250 was the spitting image of the 1975 CR250M.

A large 3.4-gallon tank gave the MR250 a pudgy profile but close to 100 miles of range on the trail. Photo Credit: Honda

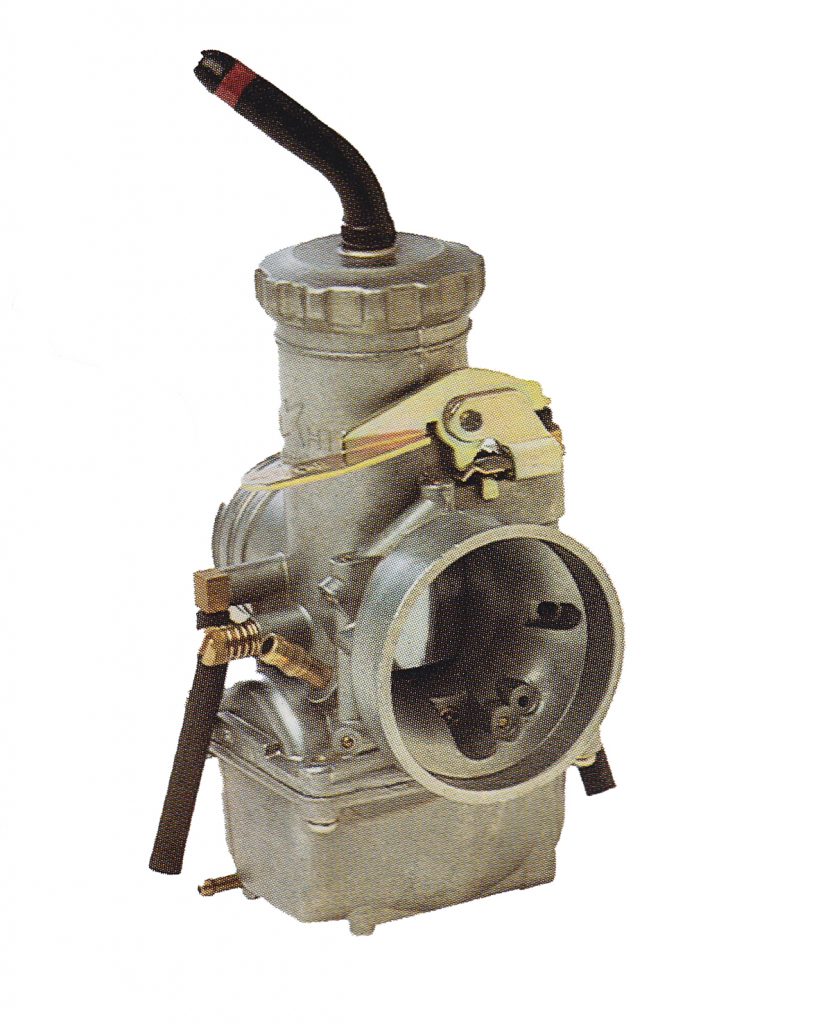

In order to make the MR more suitable for off-road competition, Honda made several subtle changes to the CR’s 248cc piston-port power plant. The bore and stroke remained identical (70 x 64.4mm), but the MR featured a slightly lower compression ratio (7.2:1 for the CR vs. 6.9:1 on the MR). The porting was also altered to improve torque and mellow out the motocrosser’s midrange hit. In order to accomplish this, the engineers lowered the CR’s exhaust ports 2.4mm and narrowed them slightly. The intake timing was also altered slightly by raising the rear boost port 1.3mm. Neither motor had the benefit of a reed-valve, but the MR did get the benefit of a “power jet” in its 34mm Keihin. This was employed to give the MR a boost in fuel supply below 4000 rpm and improve low-end power (Honda would bring a more advanced electronically-controlled version of this back twenty-one years later on their all-new 1997 CR250R).

Power Jet: The 34mm Keihin carburetor on the MR250 featured a very early version of the “Power Jet” that would be seen two decades later on Honda’s 1997 CR250R. This secondary jet circuit was designed to fill in the transitions from the pilot circuit to the main jet and give the bike a boost in low-to-mid power. Photo Credit: Honda

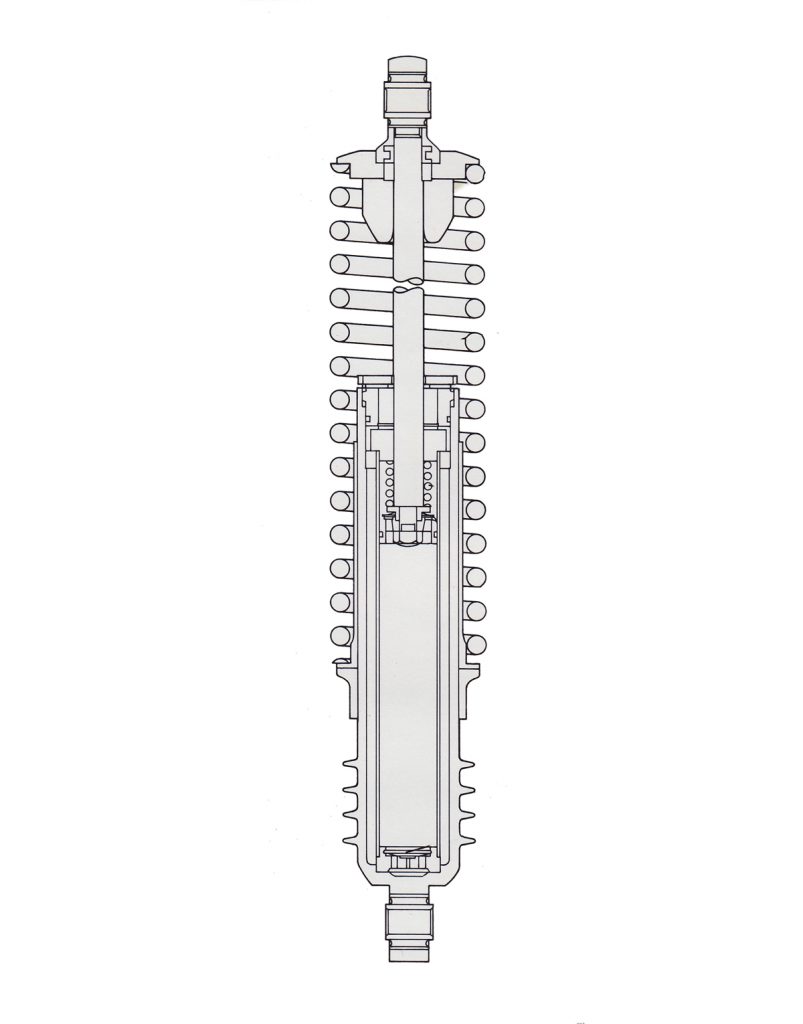

The Showa shocks on the MR were the same units found on the CR250M. They offered three settings for spring preload, but no adjustments for damping. Photo Credit: Honda

A massive spark-arrested silencer on the MR kept sound down to 86db but choked off power and added five pounds of unwanted weight. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the trail, all these changes added up to an excellent off-road powerband. At a peak of 21.86 horsepower, it put out 5.62 ponies less than the CR250M on the same dyno but offered a far wider spread of usable thrust. At 3500 rpm, the MR pulled out a two foot-pound torque advantage over the CR and it maintained that advantage up until 6500 rpm, when the CR finally pulled back ahead. On top-end, the CR walked away, but the MR could close the gap a little by ditching the stock boat anchor of a silencer for a freer-flowing alternative. Unlike the CR, the MR was happy to idle along all day and plonk around at a snail’s pace. With its low first gear, different ignition, and revised porting, the MR could be lugged way down past the point where the CR would have begun to buck and cough in protest.

The MR250’s Showa shocks featured cooling fins on the bottom of each damper that looked trick, but didn’t seem to do much to prevent fading. Photo Credit: Honda

Daredevil: Actually leaving the ground on the MR250 Elsinore was best left to Evel Knievel types. Both ends were incredibly soft and underdamped for anything above a trail pace. Photo Credit: Honda

The MR’s 248cc piston-port mill put out a broad and torquey spread of power. Its powerband was less potent on top but stronger down low and through the middle. Photo Credit: Honda

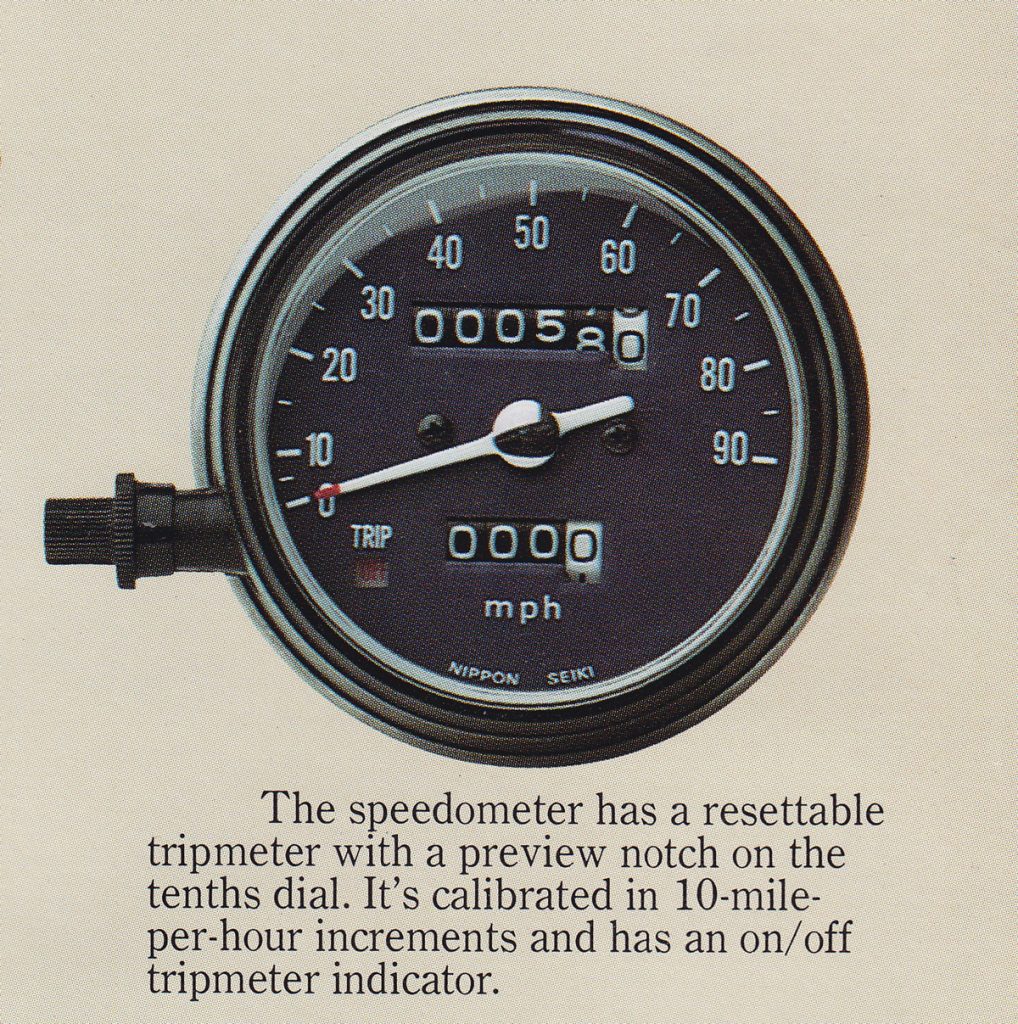

Because of its intended use as an Enduro racer, the MR came equipped with a standard speedometer and odometer. Photo Credit: Honda

Overall, MR’s motor was no rocket but it worked very well in its intended mission. It was reliable, reasonably powerful, and easily modified. For trail riding and tight Eastern enduro competition it was an excellent power plant. Thankfully, if you needed more, it was only a CR parts bin away.

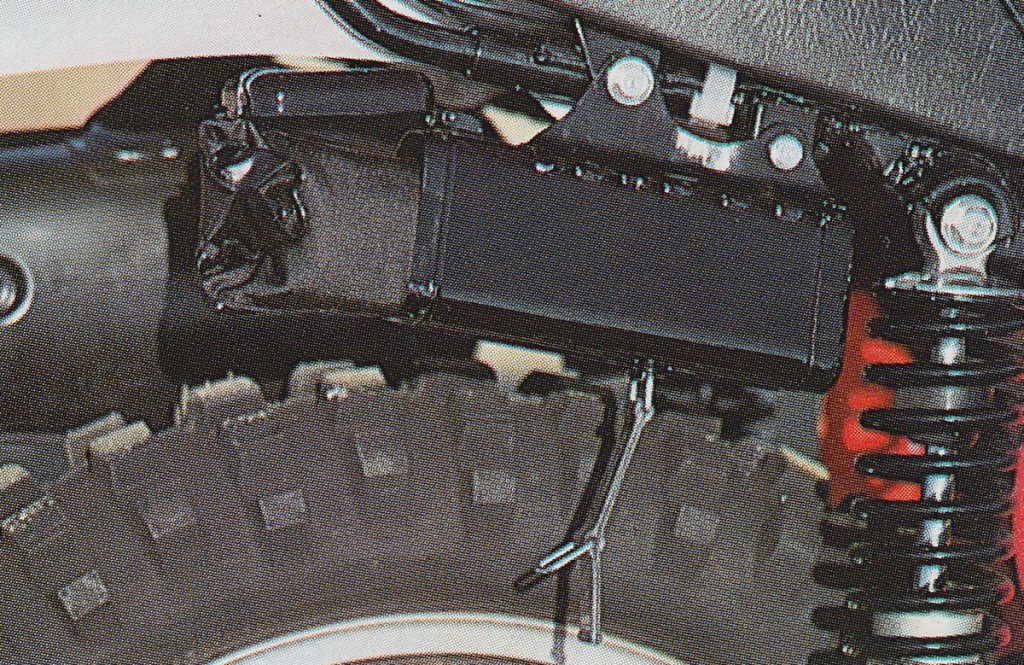

A handy tool kit was mounted opposite the gargantuan muffler and housed the tools necessary for basic trail repairs. Photo Credit: Honda

The stock Showa shocks on the MR250 were under-sprung and badly underdamped for the bike’s 248-pound dry weight. If you were going to do anything more than putt around the back forty on your MR250, a set of aftermarket shocks were a must. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Unfortunately, on the suspension end of things, it was less rosy for the MR250. By 1976, the suspension revolution had begun in earnest and “long travel” had become the buzzword of the industry. In the GPs, Yamaha’s revolutionary Monoshock had shown the industry just how much of an advantage having more travel could be and all the other manufacturers were scrambling to catch up. In the case of Honda, however, the stubborn industrial giant had been slow to catch on to this innovation. Even as Suzuki and Yamaha doubled suspension travel, Honda had stuck steadfastly to old technology and inferior performance.

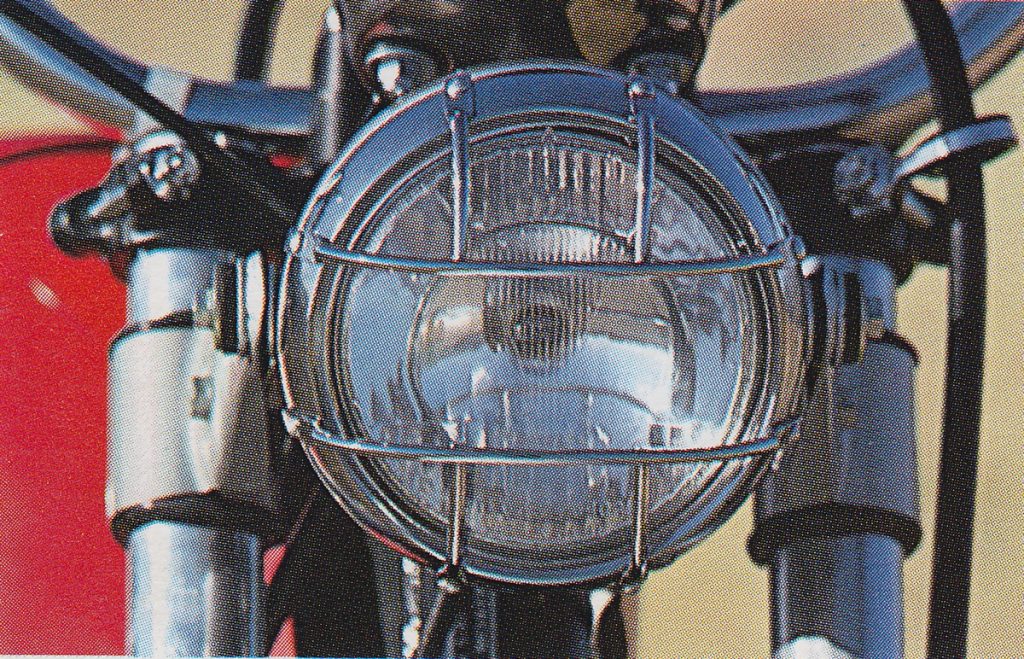

A stone guard for the front headlight was standard equipment on the MR250. Photo Credit: Honda

This meant that when the 1976 MR250 Elsinore inherited the ’75 CR’s suspension, it was already getting outdated technology. While the 7.1-inches of travel up front and 5.4-inches in the rear were less than awe-inspiring, the real issue with the Honda’s suspension was its damping performance. Even on the lightweight CR, the press had panned these forks and shocks. They were harsh, prone to fading, and the weakest link in the CR250M’s motocross package.

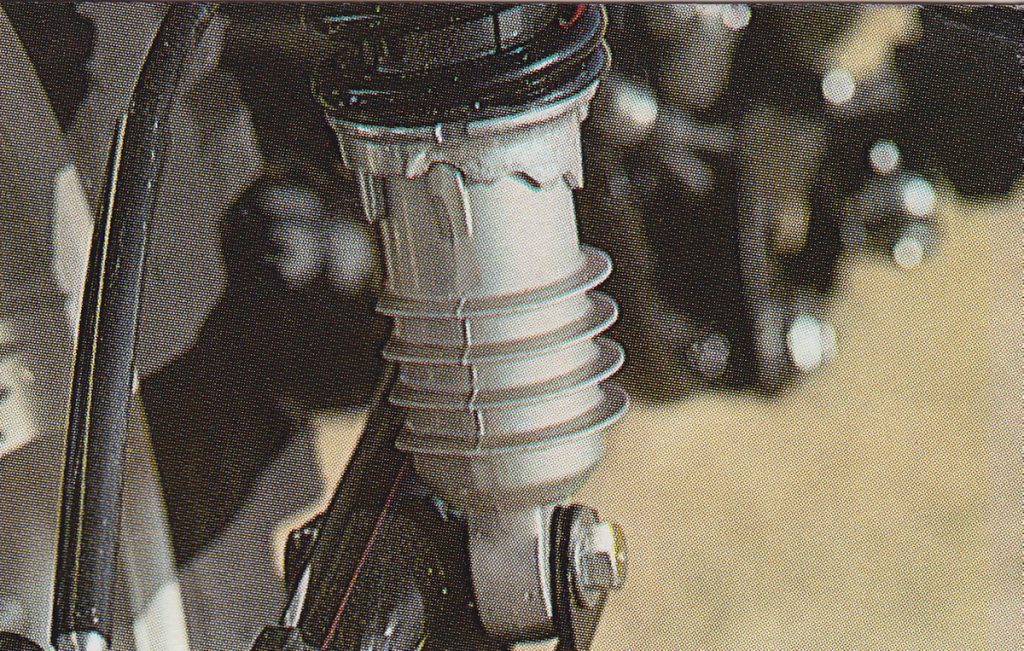

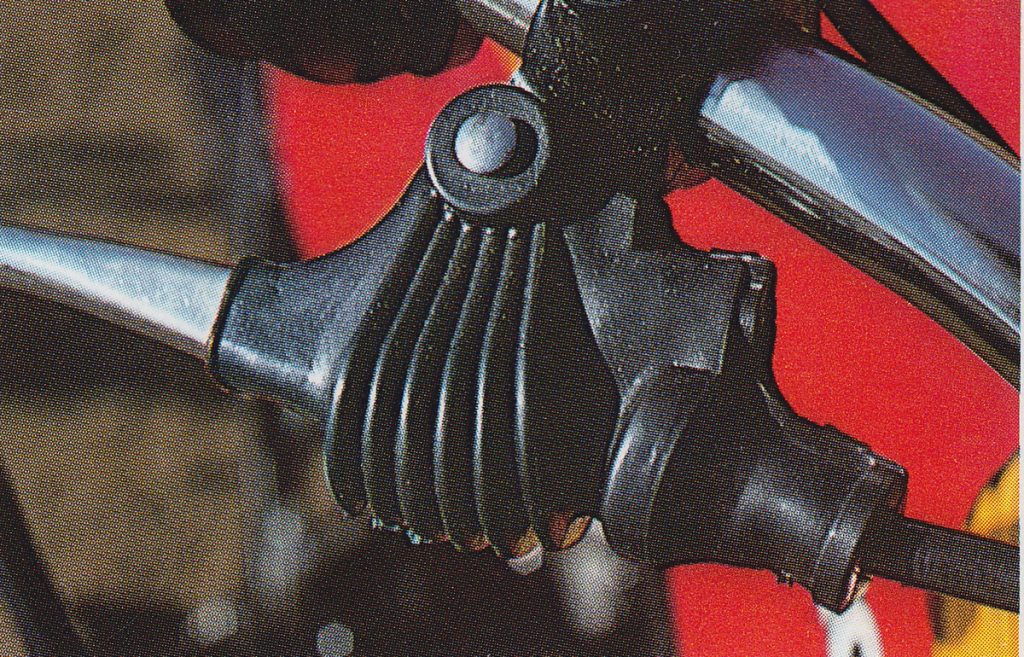

Sano: Cool features like this rubber dust cover helped keep dust, mud, and grime out of the MR’s perch and cables. Photo Credit: Honda

When setting up these Showa units for the MR, the only thing Honda changed was to install a slightly lighter spring in the front forks. While normally this would lead to an objectionably stiff ride off-road, the MR’s additional thirty-four pounds of curb weigh more than offset the motocrosser’s firmer suspension valving. On the trail, these units were badly overmatched by the bike’s substantial 248-pound girth. Both the front forks and rear shocks were woefully underdamped and incapable of maintaining moderate control in the rough. Any sort of whoops resulted in the MR pogoing up-and-down like a kid on a trampoline. Leaving the ground for any reason was inadvisable unless you were prepared for a tooth-rattling impact.

After the demise of the MR250 (right) at the end of the ’76 season, the CR125-derived MR175 (left) remained as the only performance two-stroke Enduro racer in Honda’s lineup. Photo Credit: Honda

In spite of the cooling fins on the rear shocks, these units were only good for very light riding and any sort of vigorous pace resulted in what little damping they started with going completely away. For really slow cow trailing, they were adequate enough, but if you had any pretentions about chasing down your buddy on his Penton, you had better budget in some money for aftermarket help.

With a set of aftermarket shocks, some fork tuning and a smattering of CR250 parts, the MR250 Elsinore became a potent off-road racer. Photo Credit: Mecum

Aside from its dreadful suspension, the MR250 Elsinore handled very well for its time. The CR geometry gave the bike good turning on tacky terrain and a nimble feel for a nearly 250-pound machine. In the dry, the front end was less precise and it was hard to judge if it was going to hold or wash out suddenly. In truth, without a significant upgrade in suspension, it was difficult to evaluate the performance of the chassis fairly. In stock condition, the bike was unpredictable in the rough and a real handful. Once fitted with better shocks and dialed-in forks, the bike could be a viable off-road weapon, but with the stock components in place, it was a crash waiting to happen.

Forty years before it became en vogue, Honda had the formula for the ultimate off-road racer. Unfortunately, MR250 Elsinore would never get the chance to live up to that full potential.

Of all the curiosities of the 1976 Honda MR250 Elsinore, by far the biggest is its incredibly abbreviated run in Honda’s lineup. After splashing onto the scene in 1976, it was just as quickly put out to pasture at the end of the ‘76 season. In spite of the fact that there certainly had to be a market for a bike like the MR250, Honda elected to discontinue it after only one year. For 1977, its smaller sibling the MR175 would remain, but Honda would never again offer a serious 250 two-stroke woods racer to the buying public. Rare, unique, and in many ways before its time, the 1976 MR250 Elsinore remains one of the most interesting machines in Honda motorcycling history.

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram – @TonyBlazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com