For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s first water-cooled Open bike, the mighty 1985 CR500R.

For 1985, Honda beefed up their already potent Open class package with an all-new motor, redesigned chassis, and sexy new bodywork. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1985, Honda beefed up their already potent Open class package with an all-new motor, redesigned chassis, and sexy new bodywork. Photo Credit: Honda

Today, the 500cc two-strokes are things of legend. A hairy-chested throwback to an era when men were men and bikes were brutes. Just starting one of these beasts could be an ordeal and dealing with their abrupt power delivery, mind-numbing vibration, and eye-watering acceleration was more than enough to scare most riders back to the 250 class.

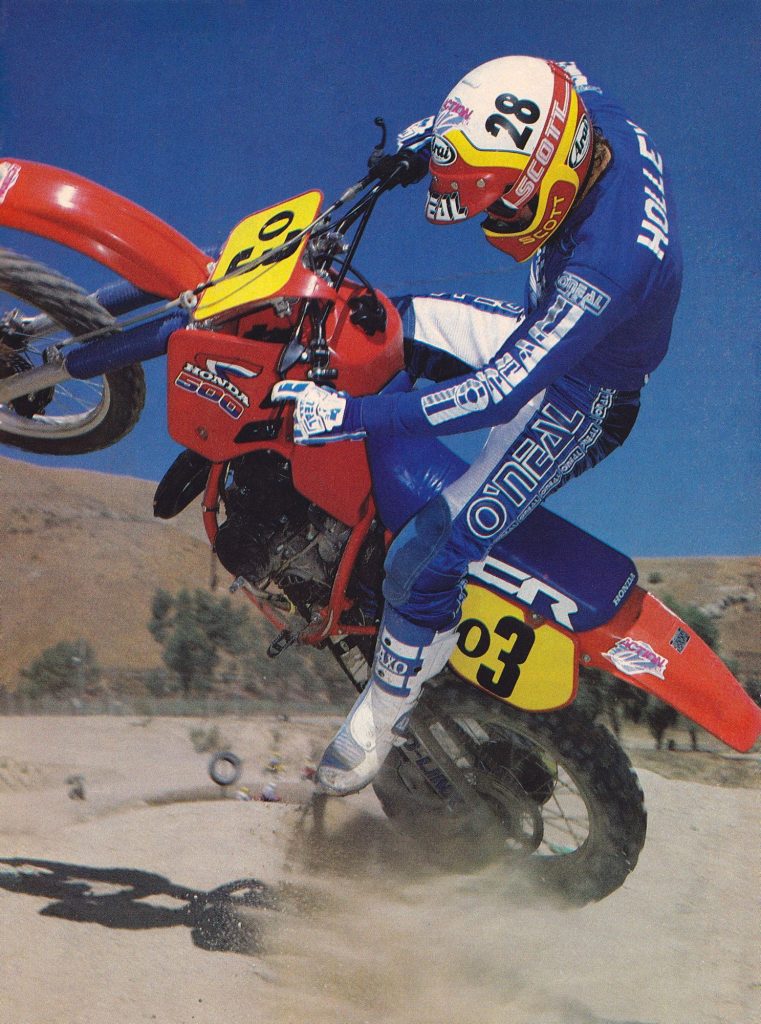

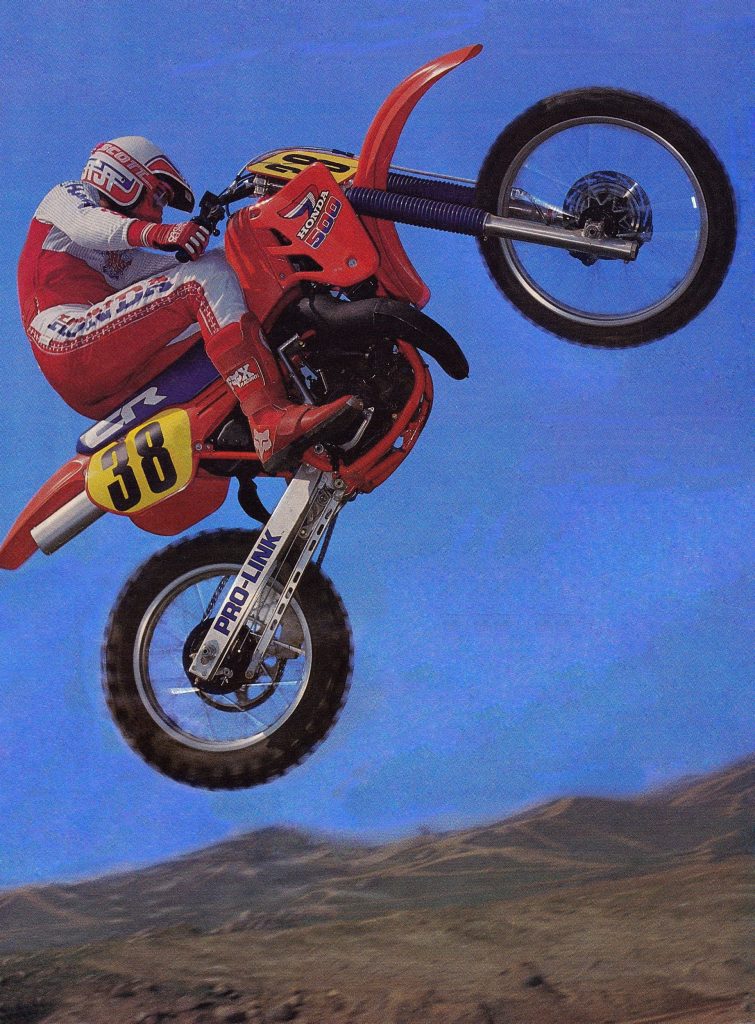

In 1985, it took a talented rider like Jim “Hollywood” Holley to harness the power of the mighty CR500R. Even today, this machine is revered (and feared) for its incredibly strong powerband. Honda would spend the next sixteen years smoothing, polishing, and refining the power from this 491cc brute. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1985, it took a talented rider like Jim “Hollywood” Holley to harness the power of the mighty CR500R. Even today, this machine is revered (and feared) for its incredibly strong powerband. Honda would spend the next sixteen years smoothing, polishing, and refining the power from this 491cc brute. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1984, no machine in motocross embodied this terrifying proposition more than Honda’s CR500R. This air-cooled beast was impossible to start, impossible to jet, and nearly impossible to ride. For Honda aficionados, this came as quite a surprise after their world-beating 1983 offering had dominated the standings. The ’83 CR480R had been light (lighter than many of the other brand’s 250s), sharp handling, quasar fast, and brutally effective. For 1984, Honda had thrown all of that out the window with an all-new Open class machine. The redesigned CR500R was bigger, badder, and just plain worse in nearly every way.

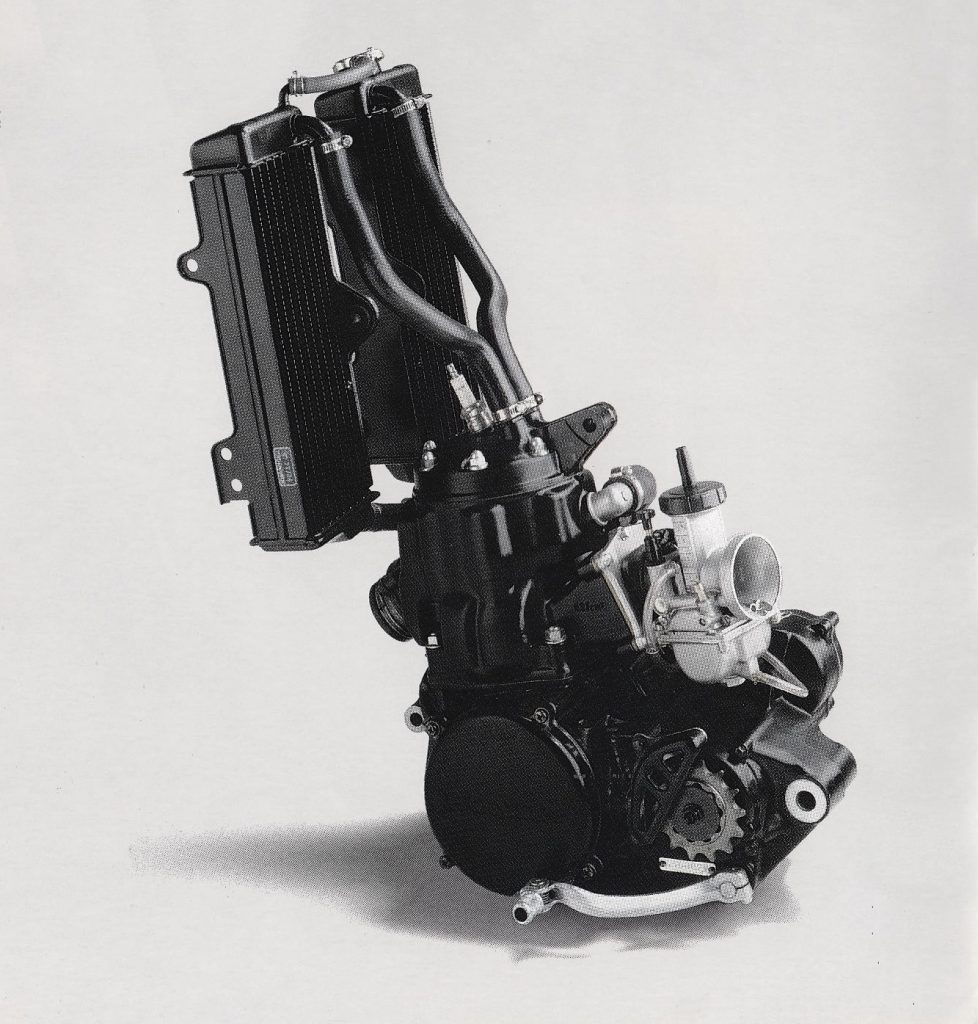

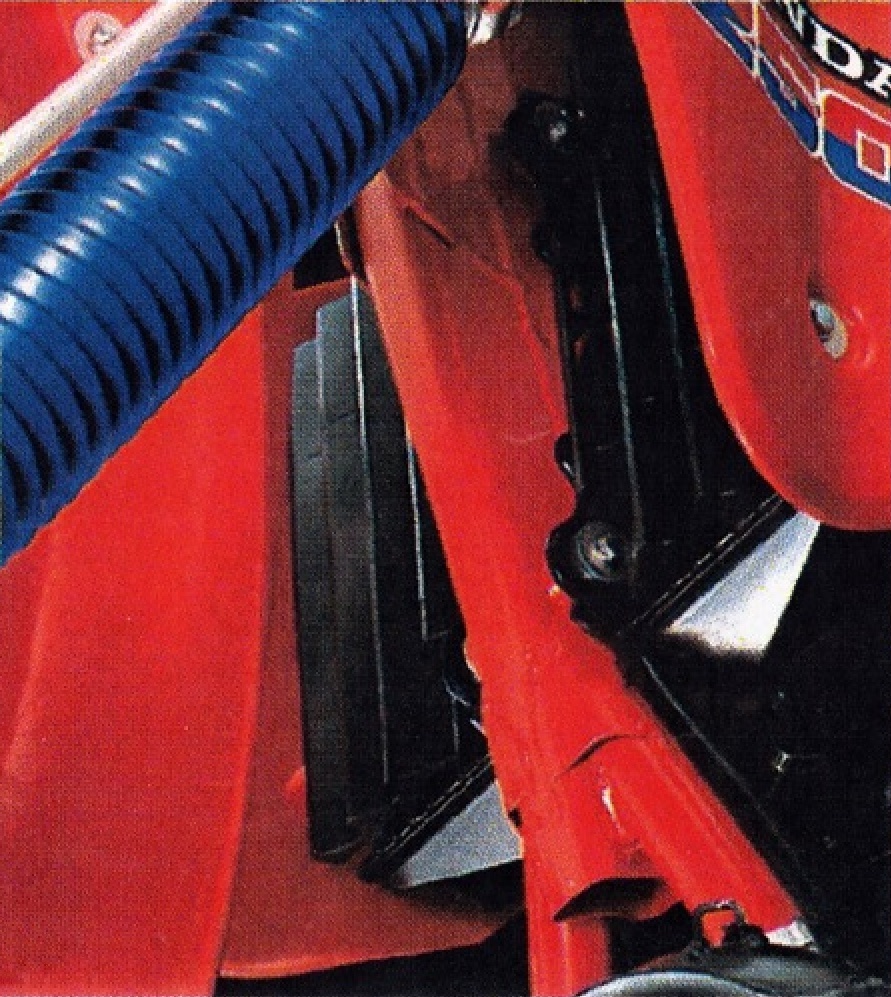

The CR500R’s new motor added liquid cooling for the first time in 1985. What it did not get, however, was the ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) system found on the smaller CRs. While innovative, the ATAC’s variable exhaust valve was a pain to clean and by most estimates of dubious effectiveness, so its exclusion was seen by many at the time as more of a benefit than a detriment. Photo Credit: Honda

The CR500R’s new motor added liquid cooling for the first time in 1985. What it did not get, however, was the ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) system found on the smaller CRs. While innovative, the ATAC’s variable exhaust valve was a pain to clean and by most estimates of dubious effectiveness, so its exclusion was seen by many at the time as more of a benefit than a detriment. Photo Credit: Honda

The all-new air-cooled 491cc motor was incredibly powerful, but difficult to control, prone to constant detonation and notoriously finicky to start. It was also poorly suspended, unreliable, vibrated like it had marbles in the motor, and shook its head like a wet dog. Even pros found it a handful and nearly everyone longed for the much better ’83 model.

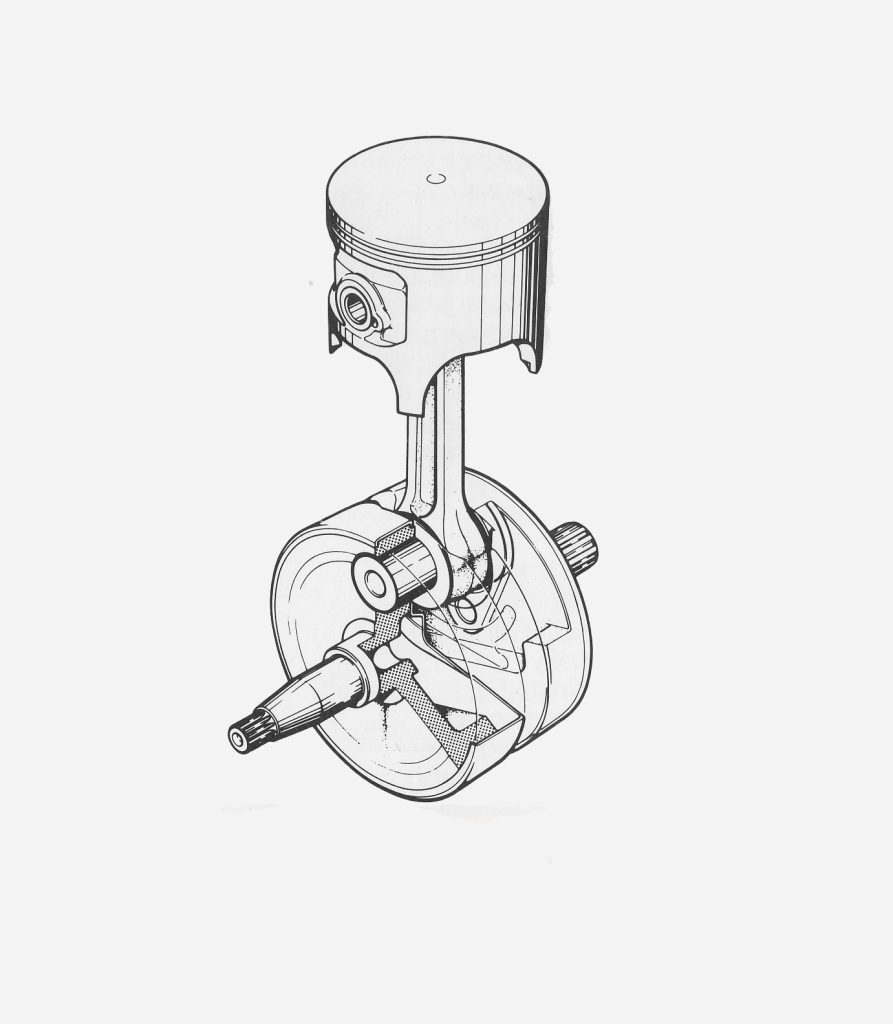

In addition to the liquid cooling, a new crank was installed that did away with the 1984’s failure-prone plastic retainers in favor of more durable steel alternatives. Photo Credit: Honda

In addition to the liquid cooling, a new crank was installed that did away with the 1984’s failure-prone plastic retainers in favor of more durable steel alternatives. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1985, Honda had several goals in mind for their half-liter problem child. First up was to get the motor sorted and iron out all the annoying carburation and starting issues of the ‘84. In order to do that, the engineers dialed up an all-new liquid-cooled motor that maintained the same 89.0 x 79.0mm bore and stroke of old the air-cooled version, but bumped up the compression slightly from 6.7:1 to 7.4:1. The addition of liquid cooling allowed the engineers to keep the motor temperatures lower and more consistent, both improving carburation and lessoning detonation. Inside the top end, new porting was spec’d and a bridge was added to the exhaust port to address the piston cracking issues of ’84. A new piston was also employed that featured 10% less silicone content to improve durability and increase heat resistance. Unlike the rest of the CR lineup, the new CR500R did without Honda’s ATAC variable exhaust valve. While this probably cost it a bit in the trickness quotient, it did simplify maintenance for prospective owners already daunted by the additional hassles of liquid cooling.

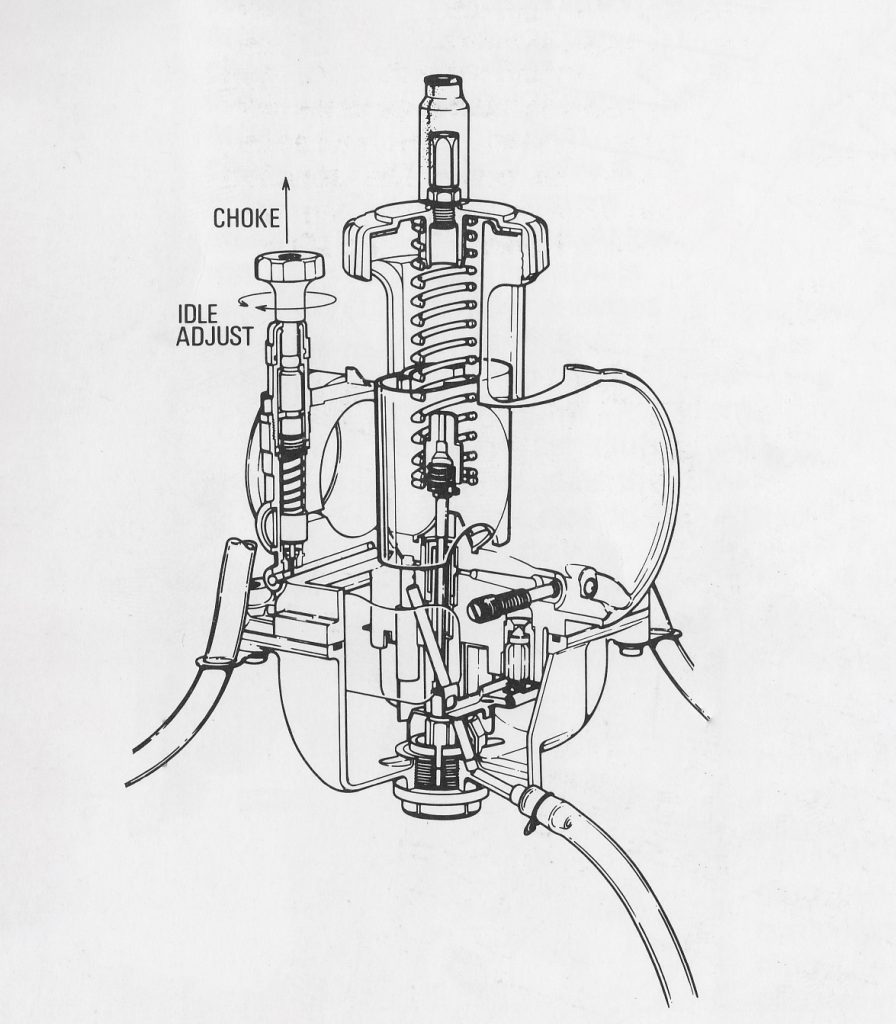

In 1984, the stock CR500R was beset with terrible jetting issues that made dialing in the bike difficult. For 1985, an all-new 38mm Keihin PJ “flat-slide” carburetor promised an end to the blubbering, popping and pinging of ’84.

In 1984, the stock CR500R was beset with terrible jetting issues that made dialing in the bike difficult. For 1985, an all-new 38mm Keihin PJ “flat-slide” carburetor promised an end to the blubbering, popping and pinging of ’84.

In the bottom end, an all-new hollow crank was installed that ditched the failure-prone plastic retainers of the ’84 in favor of more durable steel alternatives. The transmission maintained the five-speed layout it had employed since 1983 and featured widened shift forks and reinforced engagement dogs for improved durability and better shifting under acceleration. In order to improve starting, the kickstarter was lengthened and the starter gear ratio was also altered to spin faster. Finishing off the engine changes were new cases that incorporated a water pump for the first time.

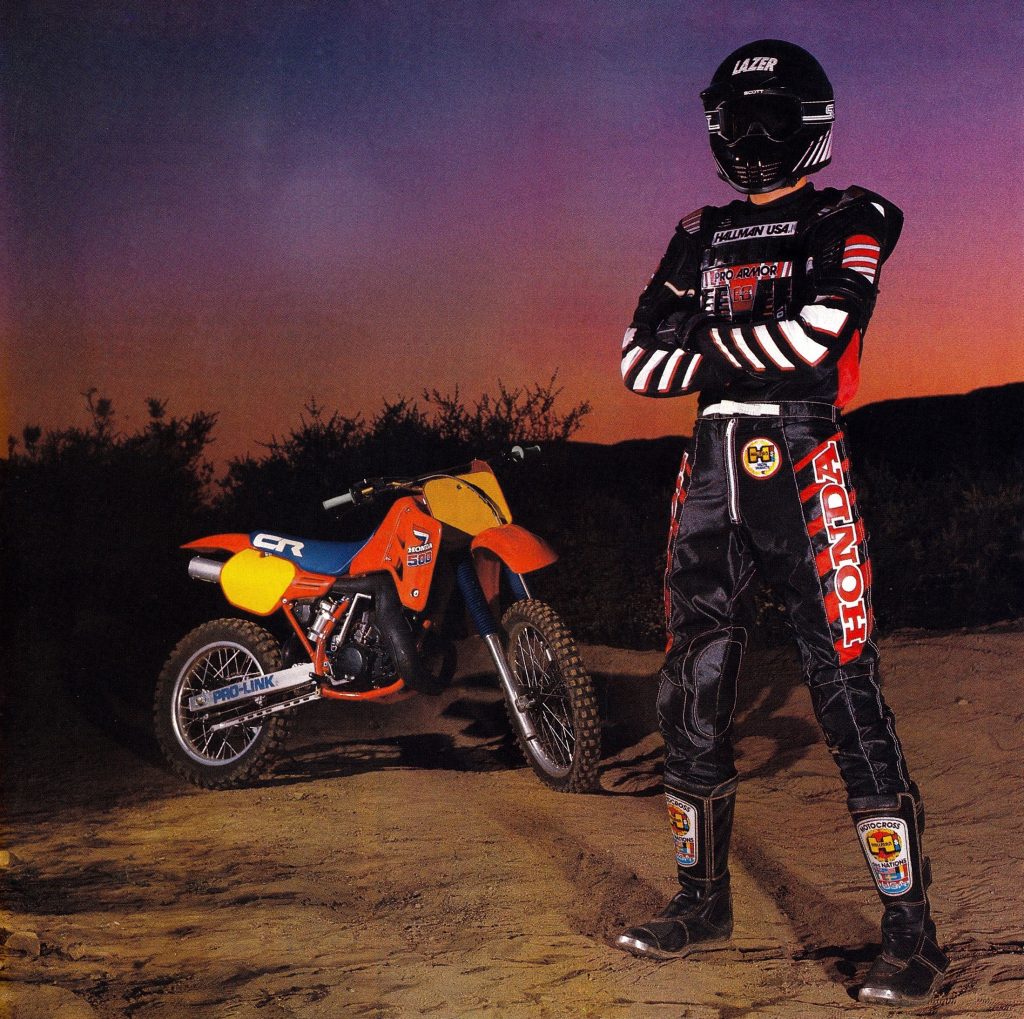

Wimps need not apply: In 1985, no machine in motocross was as manly and menacing as Honda’s mighty CR500R. Photo Credit: Hallman USA

Wimps need not apply: In 1985, no machine in motocross was as manly and menacing as Honda’s mighty CR500R. Photo Credit: Hallman USA

In an effort to exorcise the carburation woes of the ’84, Honda completely redesigned the intake on the 1985 CR500R. The 1984’s metal reeds were ash-canned and replaced with a set of lighter and more responsive fiberglass reeds. The old machine’s problematic 38mm Keihin “round-slide” carburetor also got the boot. In its place, Honda bolted on Keihin’s all-new 38mm “flat-slide” PJ carb. This new carburetor promised improved throttle response and easier tuning. Feeding air to the new mixer was a redesigned airbox that offered a larger opening for increased airflow and easier service. Lastly, an all-new exhaust system was installed to match the redesigned power plant.

A redesigned frame for 1985 featured a new boxed-in downtube for increased rigidity. Photo Credit: Honda

A redesigned frame for 1985 featured a new boxed-in downtube for increased rigidity. Photo Credit: Honda

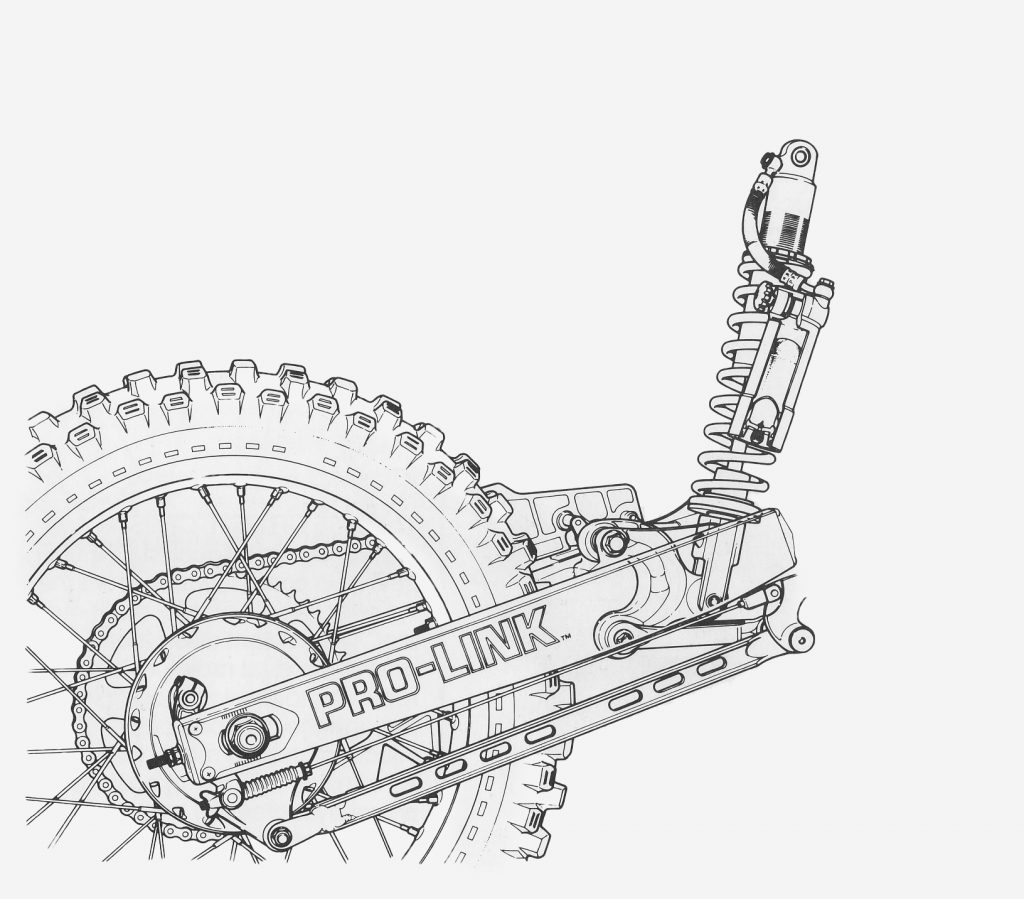

On the chassis side, the ’85 CR500R featured a new frame with revised geometry and a more spacious layout. When spec’ing the new frame Honda’s engineers repositioned the steering head 10mm farther forward and added 0.3 degrees more rake than ’84. The main frame down tube was also switched from round to square tubing to increase strength. Both the steering head and swingarm pivot were beefed up, but other portions of the frame offered thinner tubing in strategic areas to save weight. In the rear, an all-new Pro-Link linkage was bolted on with high-quality needle bearings replacing the plain bearings of 1984. The shock’s mountings were also upgraded from rubber bushings to new spherical heim-type joints for reduced stiction and increased durability. The new linkage featured a flatter curve and slightly longer travel (12.6-inches vs. 12.4-inches in ’84) for ’85. Matched to the linkage was an all-new Showa remote-reservoir shock that featured a 4mm larger piston and 12.7mm longer stroke than in ’84. The new shock featured external adjustments for compression (18 settings) and rebound (21 settings) damping as well as preload. Internally, the new shock also featured an “automatic temperature compensating valve” that was designed to increase compression and rebound damping once the shock got hot to fight the fading the ’84 version suffered from.

Honda had major changes on tap for their Pro-Link rear suspension in 1985. To reduce drag, Honda upgraded all the pivot points from plain bearings to roller bearings and revised the ratio of the linkage to improve cornering and provide a more progressive action. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda had major changes on tap for their Pro-Link rear suspension in 1985. To reduce drag, Honda upgraded all the pivot points from plain bearings to roller bearings and revised the ratio of the linkage to improve cornering and provide a more progressive action. Photo Credit: Honda

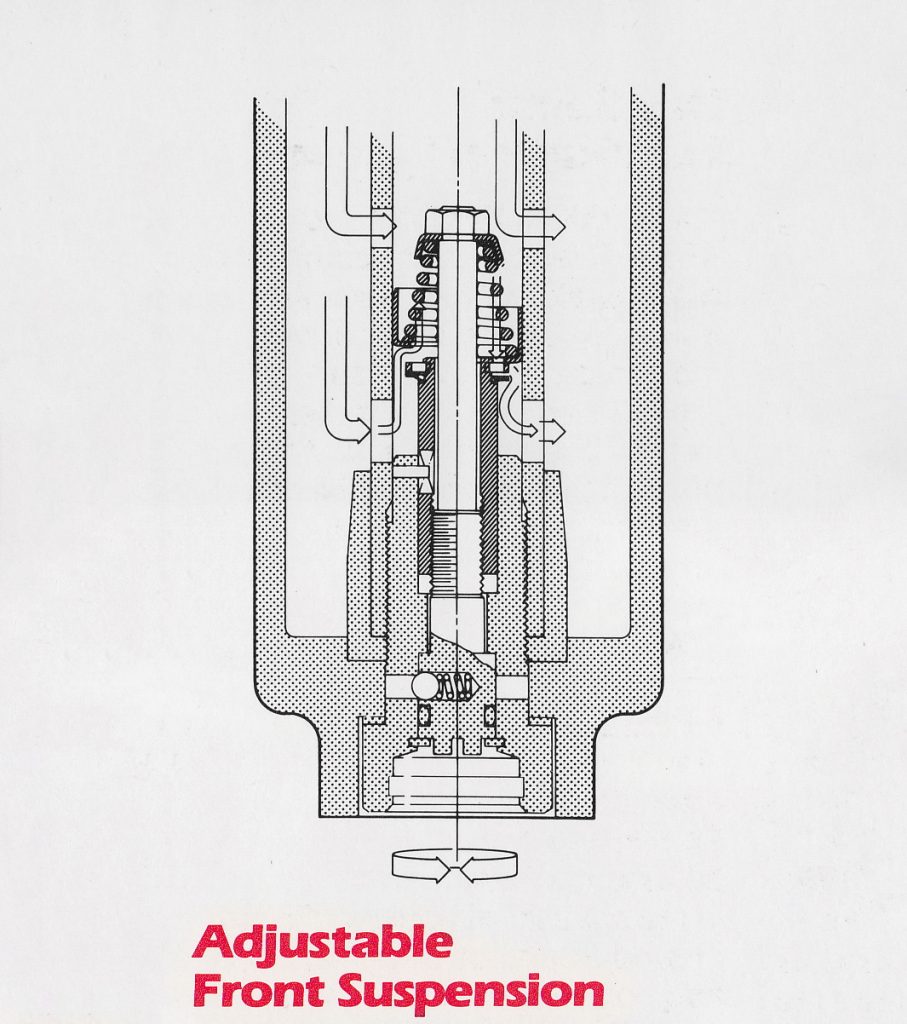

Up front, a set of 43mm conventional Showa forks handled the suspension duties. These units punched out 12 inches of travel and offered air-adjustability and 12 settings for compression (there was no external adjustment available for rebound). With the arrival of Showa’s award-winning cartridge dampers still a year away, the ’85 CR had to make due with damper rods for compression and rebound control.

The 1985 CR500R’s Showa forks offered adjustments for compression damping and air pressure, but none for rebound. Photo Credit: Honda

The 1985 CR500R’s Showa forks offered adjustments for compression damping and air pressure, but none for rebound. Photo Credit: Honda

The Little Professor: Even pilots as skilled as multi-time National Motocross champion David Bailey preferred to have the CR500R’s massive hit mellowed out in 1985. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

The Little Professor: Even pilots as skilled as multi-time National Motocross champion David Bailey preferred to have the CR500R’s massive hit mellowed out in 1985. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

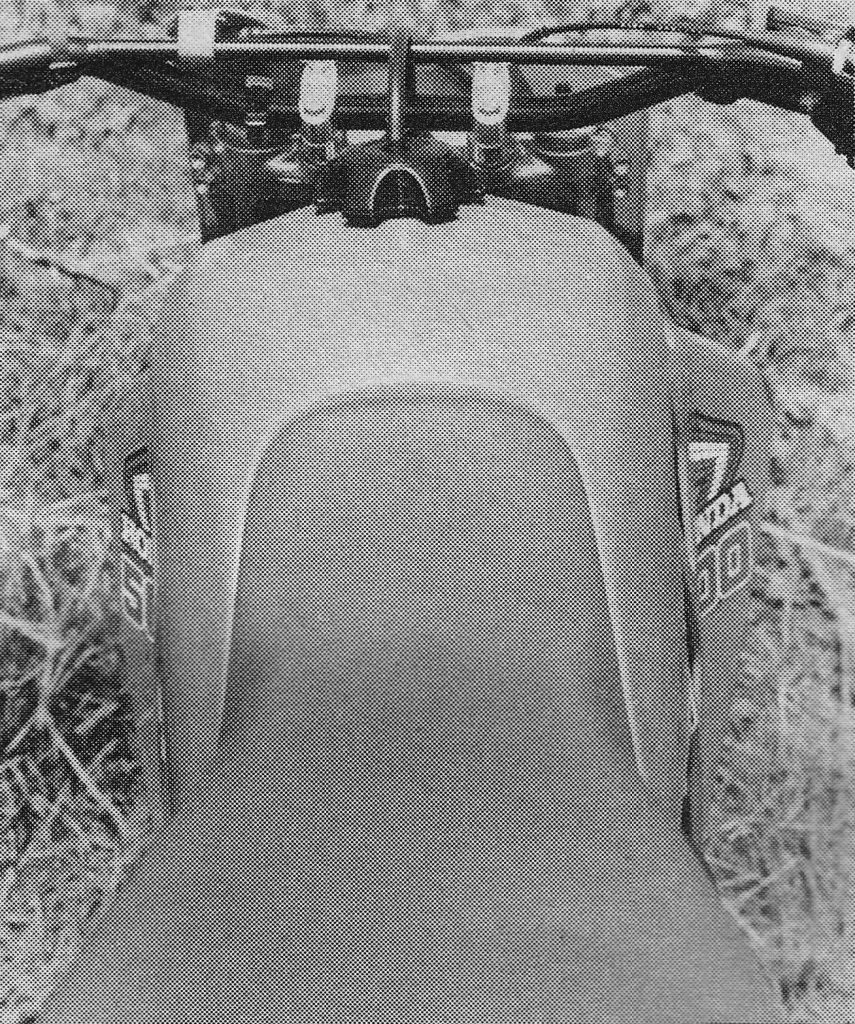

Finishing off the ’85 package was all-new bodywork that looked amazing, but left a bit to be desired in the ergonomics department. The arrival of the CR’s new radiators and the thirstiness of the 491cc mill dictated a new tank that bulged out prodigiously; compared to the ’84, the new tank was wider, steeper, and pushed farther back into the seating compartment. This made it harder to get forward in turns and gave the machine a very porky feel that no one particularly liked. Because the radiators were taller and positioned higher, just swapping to the more streamlined CR250R tank was also not an option.

While the testers approved of most of the CR500R’s new bodywork, its new tank proved a blemish on an otherwise excellent package. Big, bulging and ultra-wide, this unit splayed out your legs and made sliding forward far more difficult than the year before. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the testers approved of most of the CR500R’s new bodywork, its new tank proved a blemish on an otherwise excellent package. Big, bulging and ultra-wide, this unit splayed out your legs and made sliding forward far more difficult than the year before. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the track, the new CR500R turned out to be much improved in some areas and only mildly upgraded in others. First up on the list of improvements was the new motor, which ran far cleaner than the old air-cooled version had. The new mill suffered none of the carburation issues of the ’84, barking out a throaty, quick-revving, and ultra-powerful flow of ponies from its nearly half-liter of displacement. The blubbering, pinging and rattling of the ’84 was completely absent in the new mill. With the new PJ carburetor, a revised intake, and a light flywheel, the redesigned power plant provided lightening fast response and super crisp performance. Power out of the hole was incredibly abrupt, with a massive rush of torque available from the first crack of the throttle. That low-end blast carried into the midrange with a tidal wave of furious acceleration. Once past the midrange explosion, the big red beast preferred to be shifted rather than revved out. In the midrange, it pumped out a whopping seven more horsepower than in ’84 and only gave up that lead at the upper fringes of the powerband, where all but the criminally insane feared to tread.

In spite of its ginormous tank, the 1985 CR500R was one pretty beast. Photo Credit: Luis Vargas

In spite of its ginormous tank, the 1985 CR500R was one pretty beast. Photo Credit: Luis Vargas

In spite of lacking any sort of “power valve,” the ’85 CR’s 491cc mill pumped out tire-shredding performance. It was incredibly strong down low and brutally powerful in the midrange. Top-end power was somewhat lacking, but only really fast (and brave) riders were likely to notice. Photo Credit: Honda

In spite of lacking any sort of “power valve,” the ’85 CR’s 491cc mill pumped out tire-shredding performance. It was incredibly strong down low and brutally powerful in the midrange. Top-end power was somewhat lacking, but only really fast (and brave) riders were likely to notice. Photo Credit: Honda

With its explosive low-end response and tire-torturing midrange, the ’85 CR500R could be a real handful for those of lesser talent to manage. If you were carless or tired, an inadvertent whack of the throttle was likely to put you on your head in short order. On hardpack, it was necessary to keep a gear (or two) high to prevent lighting up the rear tire, and in loam, it was just as necessary to lug it to prevent looping it out. The light flywheel made it easy to stall and difficult to modulate. Even long-time Open class riders found the machine a challenge to control and most hop-up shops went looking for ways to mellow it out rather than pump it up. If you had the skill and strength, the ’85 CR500R power plant had all the power you could ever need, but if you were a bit more mortal, it could be a real handful.

Rocket Booster: With mega doses of thrust on tap at virtually any throttle setting, the CR500R was capable of conquering any leap a rider was brave enough to attempt in 1985. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Rocket Booster: With mega doses of thrust on tap at virtually any throttle setting, the CR500R was capable of conquering any leap a rider was brave enough to attempt in 1985. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

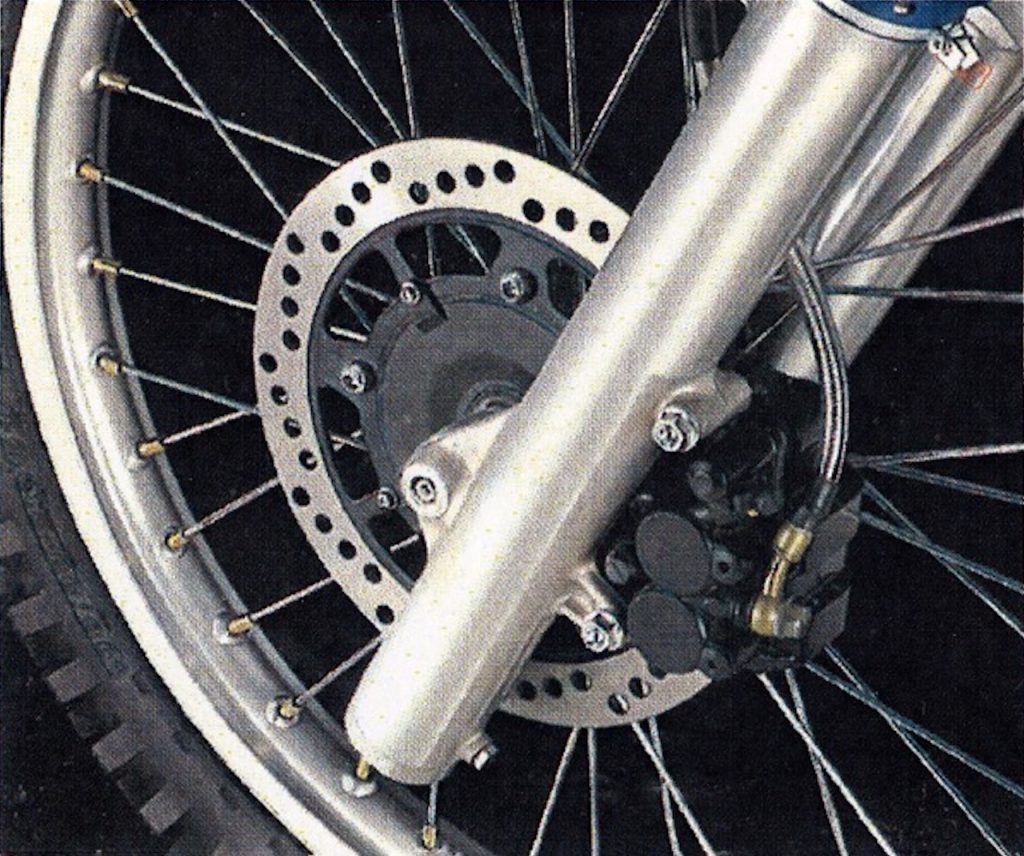

In 1985, this dual-piston Nissin front binder was the best brake in motocross. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1985, this dual-piston Nissin front binder was the best brake in motocross. Photo Credit: Honda

On the suspension end of things, the ’85 CR was far less impressive. The 43mm Showa forks were too stiffly sprung, harsh on compression and far too quick on rebound. On hard landings they hammered your hands, and on small chatter they danced around like a cat on a hot tin roof. Bottoming resistance was better than the ’84, but when they did reach the stops, they did it with a tooth-rattling clank. At the time, a spring swap and a Simons Anti-Cav kit were the hot setup and greatly improved the CR’s mediocre suspension performance.

The ’85 CR’s new liquid-cooled power plant carbureted perfectly and suffered from none of the detonation issues that had plagued it the year before. Unfortunately, the good news did not extend to its starting performance, which continued to be an exercise in frustration. Sometimes, it fired up on the first kick, and sometimes, it just coughed and laughed at you as you kicked until your leg was numb. Add in a tall and awkwardly placed kicker and you have by far the least-loved facet of the ‘85 CR’s power plant. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The ’85 CR’s new liquid-cooled power plant carbureted perfectly and suffered from none of the detonation issues that had plagued it the year before. Unfortunately, the good news did not extend to its starting performance, which continued to be an exercise in frustration. Sometimes, it fired up on the first kick, and sometimes, it just coughed and laughed at you as you kicked until your leg was numb. Add in a tall and awkwardly placed kicker and you have by far the least-loved facet of the ‘85 CR’s power plant. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Drum brakes were still de rigueur in 1985 and the CR’s rear binder was considered adequate in performance, but lackluster in longevity. New shoes for ’85 mostly eliminated the annoying squeaking of the ‘84, but wore out very quickly. Constant adjustments were required to maintain consistent performance, and a hard rider could burn through a set of shoes in a single race weekend. Photo Credit: Honda

Drum brakes were still de rigueur in 1985 and the CR’s rear binder was considered adequate in performance, but lackluster in longevity. New shoes for ’85 mostly eliminated the annoying squeaking of the ‘84, but wore out very quickly. Constant adjustments were required to maintain consistent performance, and a hard rider could burn through a set of shoes in a single race weekend. Photo Credit: Honda

In the rear, the new Showa shock was only slightly less terrible than the year before. The new linkage and damper provided a plush ride initially, but the shock suffered from a sudden spike of damping halfway through the stroke. When fresh, it also tended to pack in successive whoops and skip around. Interestingly, that was not the worst of the shock’s problems, as it continued to suffer from a massive case of the fades. After 15 minutes of hard riding, the damping went away completely and the big Honda became all but unridable. Unfortunately, no amount of knob fiddling or re-valving was going to fix this issue and most fast guys found an aftermarket shock to be the only real fix for the big five honey.

Jackhammers: With the introduction of Showa’s works-like “cartridge” damping system still a year away, the new CR500R had to make do with a set of air-adjustable damper-rod forks in 1985. These 43mm Showa units provided 12 inches of travel and thoroughly mediocre performance. Photo Credit: Honda

Jackhammers: With the introduction of Showa’s works-like “cartridge” damping system still a year away, the new CR500R had to make do with a set of air-adjustable damper-rod forks in 1985. These 43mm Showa units provided 12 inches of travel and thoroughly mediocre performance. Photo Credit: Honda

On the handling side the CR500R offered the sharpest-turning package on the track in 1985. In spite of its portly ergonomics, the super-sized sumo shredded through the turns like a bike half its size; it could turn rings around the cranky Kawasaki and ponderous Yamaha. At speed, however, the sharp geometry and lackluster suspension made for a very busy ride. When slowing down in the rough, the headshake was lock-to-lock brutal and only slightly less terrifying than the year before. In these conditions any of the other 500s were preferable to the Honda and not many people were going to line up for Baja on the CR.

An all-new shock and linkage for 1985 did very little to address the ’84 CR’s middling suspension performance. Poorly damped, prone to fading and unreliable, this unit was not up to the demands placed on it by the CR’s prodigious power and substantial weight. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new shock and linkage for 1985 did very little to address the ’84 CR’s middling suspension performance. Poorly damped, prone to fading and unreliable, this unit was not up to the demands placed on it by the CR’s prodigious power and substantial weight. Photo Credit: Honda

On the detailing side, the new CR was excellent for the time but far from perfect. The bike lacked a rear disc brake (none of the competition had them either in ’85), but new aluminum pads (replacing the 1984’s magnesium) provided strong performance and cessation of the endless squeaking of the ’84. Up front, the only dual-piston caliper in the class provided the most power and best feel of any disc available. A new three-piece throttle housing made servicing and adjustment easier while providing butter-smooth operation. The new PJ carburetor provided perfect jetting and simplified idle adjustment. The clutch was durable, smooth and trouble free and the five-speed transmission continued to be versatile and precise in action. The seat, decals, plastic and fastener quality was all top notch, with everything fitting perfectly and looking great long after the other brands looked and felt beat. Even things like the grips and quality of the levers were a cut above the class standard.

In spite of its pudgy ergos, poor suspension, and abrupt power, the CR500R could be quite the shredder. With a skilled pilot like Rob Andrews aboard, nothing was going to cut under the big red machine in 1985. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

In spite of its pudgy ergos, poor suspension, and abrupt power, the CR500R could be quite the shredder. With a skilled pilot like Rob Andrews aboard, nothing was going to cut under the big red machine in 1985. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

On the negative side were its portly tank (get used to riding bowlegged), fade-prone shock (get used to getting kicked in the gluteus maximus), absurdly abrupt power delivery (get used to having longer arms), impossible starting (get used to wanting a new leg), and vicious headshake (forget it, you will never get used to this one).

In 1985, Honda unleashed the biggest, baddest, and meanest machine ever to head their motocross arsenal. Too strong, too portly, and too demanding – the ’85 CR500R was the perfect example of the eighties excess that eventually doomed the two-stroke 500 class to the ash heaps of history.

In 1985, Honda unleashed the biggest, baddest, and meanest machine ever to head their motocross arsenal. Too strong, too portly, and too demanding – the ’85 CR500R was the perfect example of the eighties excess that eventually doomed the two-stroke 500 class to the ash heaps of history.

Overall, the 1985 CR500R proved to be an improved, but not fully tamed, beast of a machine. The new chassis was quick and the new power plant was wicked, but its rubenesque lines and subpar suspension held back a thoroughly pro-oriented package. With power to burn and stellar looks, the ’85 CR500R remains an icon of eighties overkill. It offered too much brute force and not enough finesse for most mere mortals of the time. For them, more flywheel, less hit, and better suspension were a must to make this hairy-chested monster manageable. Every year after 1985, the CR500R would become just a bit more domesticated. By the mid-nineties, Honda would have this down to a science, with the mighty CR500R a mere shadow of its unruly former self. Tall gearing, big silencers, and milder porting would turn out to be the magic formula for turning this ground-pounder into a pussycat. In 1985, however, big hair was still all the rage and big power was the name of the game. On that score, no bike in motocross was more eighties awesome than Honda’s mighty CR500R.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com