For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going take a look back at one of the best Kawasakis of the eighties, the all-new for 1984 KX125.

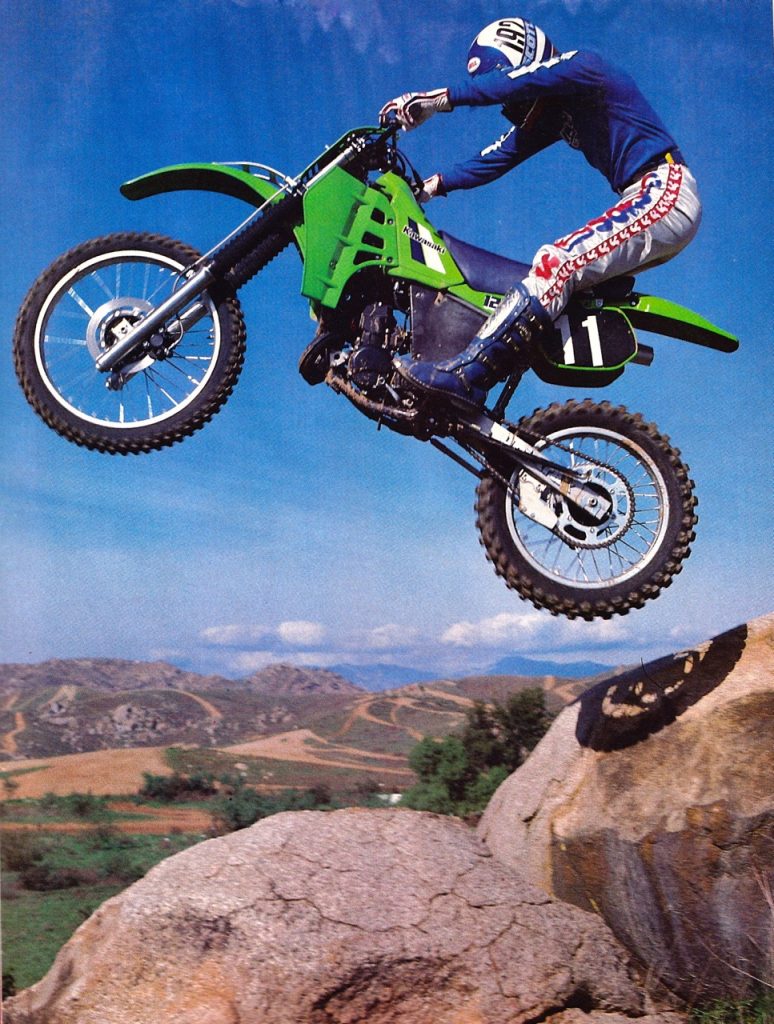

In 1984, Kawasaki released by far the most competitive full-size motocross machine ever to wear their corporate green. The all-new KX125 was wicked fast, drop-dead gorgeous, and the class of a very competitive field. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1984, Kawasaki released by far the most competitive full-size motocross machine ever to wear their corporate green. The all-new KX125 was wicked fast, drop-dead gorgeous, and the class of a very competitive field. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Today, Kawasaki holds a prominent position as one of the most-successful brands on the track. Their minis are the only Japanese ones to still give the Austrians a run for their money and their excellent KX250s and KX450s compete at the front year-in and year-out for Supercross and National Motocross titles. The green machines may still lack a little of the cachet of the Hondas, but they make up for it with a wall full of number one plates over the last two decades that dwarf what the red brand has accomplished.

Kawasaki’s styling in the early eighties was of the love-it, or hate-it variety. Machines like this 1983 KX125 offered strong motor performance wrapped in a rather unrefined package. Photo Credit: Ken Bouck

Kawasaki’s styling in the early eighties was of the love-it, or hate-it variety. Machines like this 1983 KX125 offered strong motor performance wrapped in a rather unrefined package. Photo Credit: Ken Bouck

In the seventies and early eighties, however, times were much tougher for Kawasaki’s motocross program. In spite of being the first Japanese brand to embrace the sport in the early sixties, they had failed to capitalize on this lead as Suzuki, Yamaha, and eventually, Honda raced by them to the front. Even with popular stars like “Jammin” Jimmy Weinert and “Bad” Brad Lackey on their machines, they had failed to make more than a small dent in the motocross market. The KXs were ignored by dealers and scoffed at by customers throughout most of the decade of the seventies. Some years, Kawasaki failed to even offer them for sale, and even when they were available, it was often in very small numbers.

Works Replica: The redesigned 1984 KX125 bore more than a passing resemblance to Jeff Ward’s 1983 SR125 factory racer. Photo Credit: David Lack

Works Replica: The redesigned 1984 KX125 bore more than a passing resemblance to Jeff Ward’s 1983 SR125 factory racer. Photo Credit: David Lack

As the eighties began, Kawasaki started to get far more serious about the motocross market. Production was ramped up and new bikes were designed that pushed the green machines to the forefront of motocross technology. In 1980, they became the first manufacturer to offer a linkage-equipped single-shock rear suspension system with their innovative Uni-Trak, and in 1982, they trumped the industry once again by becoming the first major brand to offer a hydraulic disc brake as standard equipment. In their green-and-gold livery the Kawasakis were bold in design and bold in appearance. On the track, that did not always translate to wins, but at least they were no longer sitting on the fences as their competitors roosted by.

At select events in 1983, the Kawasaki Factory team swapped their usual black seats for these colorful orange versions. At the time, green and orange were Kawasaki’s official corporate colors and early reports had them contemplating a move to this look for the ‘84 production models. While certainly memorable, it was eventually decided that this color combination might be a bit too bold for American consumers. Photo Credit: Unknown

At select events in 1983, the Kawasaki Factory team swapped their usual black seats for these colorful orange versions. At the time, green and orange were Kawasaki’s official corporate colors and early reports had them contemplating a move to this look for the ‘84 production models. While certainly memorable, it was eventually decided that this color combination might be a bit too bold for American consumers. Photo Credit: Unknown

For Kawasaki, their first real breakthrough actually came in the mini division. In 1983, they launched a pair of mini racers that took the world by storm and served notice that the green machines were getting serious about winning. The all-new KX60 and redesigned KX80 dominated the standings with potent powerbands, solid handling and cutting-edge styling. These two machines were blazing fast, ultra-competitive and lovely to look at – something that could rarely have been said about most Kawasaki machines up to that point.

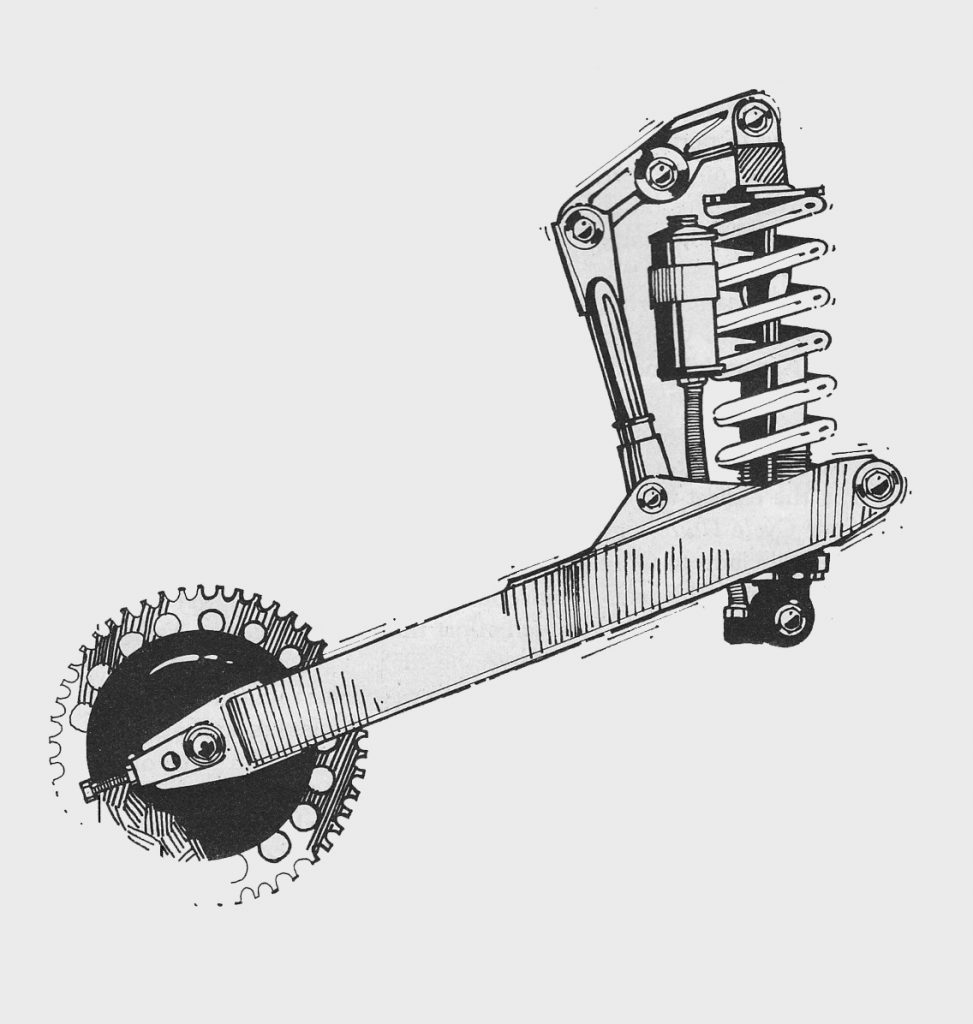

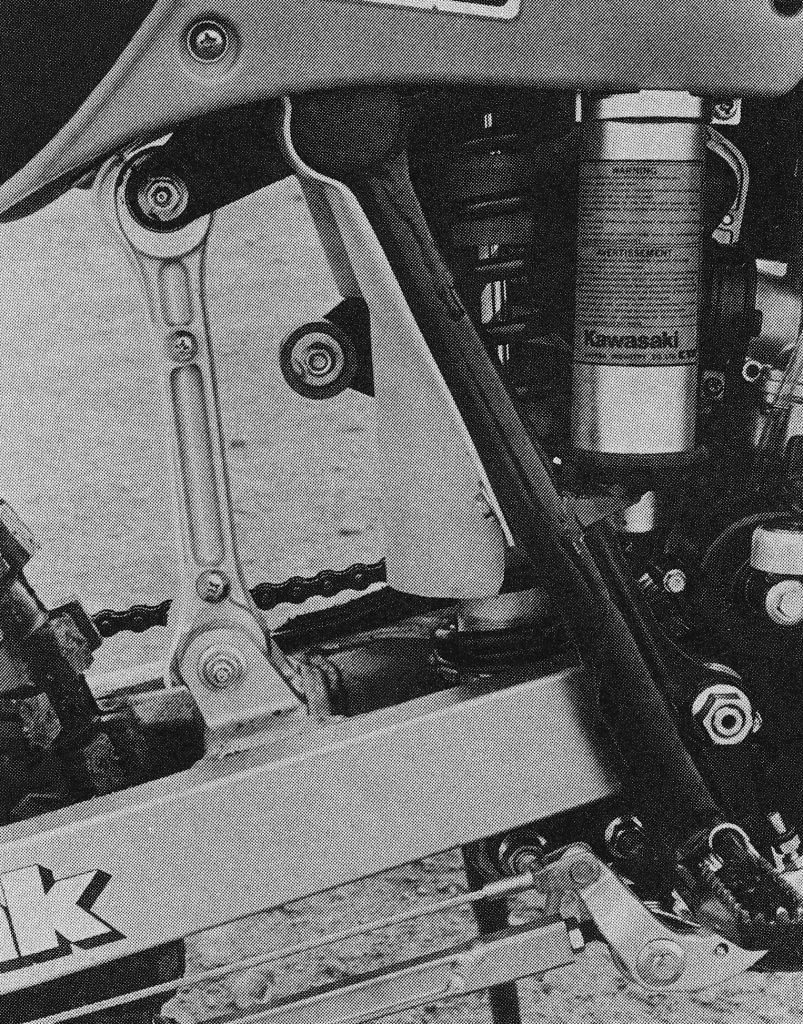

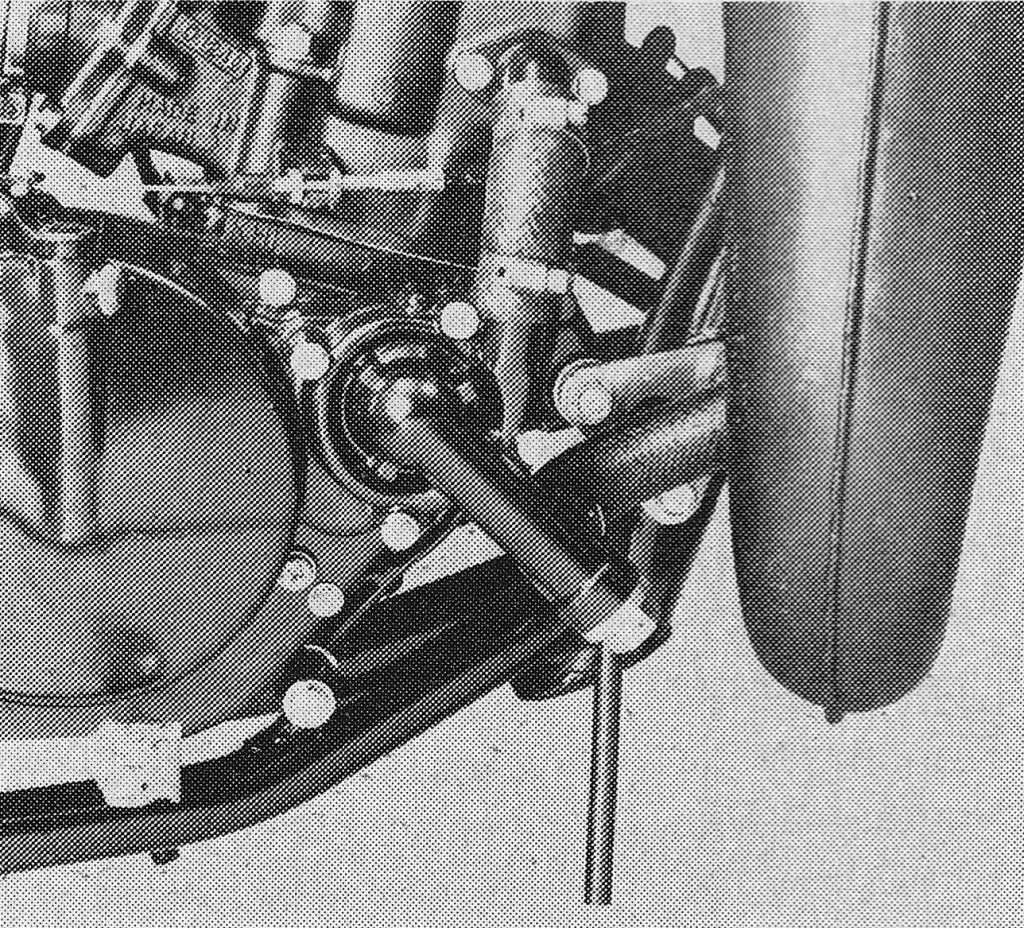

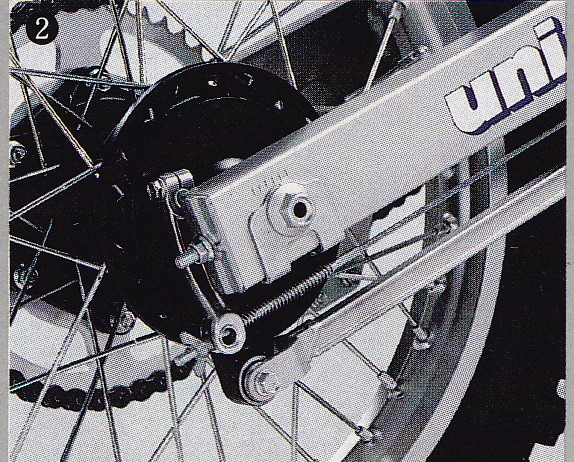

Originally introduced in 1980, Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak suspension design placed the linkage at the top of the shock instead of below the swingarm at the bottom. While the Uni-Trak was less complicated than Suzuki’s Full Floater design, it was still not as compact and space efficient as Honda’s Pro-Link configuration. Eventually, all the manufactures would move to a variation of Honda’s bottom-link design. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Originally introduced in 1980, Kawasaki’s Uni-Trak suspension design placed the linkage at the top of the shock instead of below the swingarm at the bottom. While the Uni-Trak was less complicated than Suzuki’s Full Floater design, it was still not as compact and space efficient as Honda’s Pro-Link configuration. Eventually, all the manufactures would move to a variation of Honda’s bottom-link design. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

For 1984, it was the KX125’s turn for a major redesign. In 1983, the 125 Kwacker had been a blazing-fast machine marred by several serious design deficiencies. The motor, while fast, was quick to wear out and prone to debilitating air leaks. The chassis was tall, long, and unwieldy for a 125 and the entire bike appeared to have been assembled from pot-metal Kawasaki had found on the side of the road.

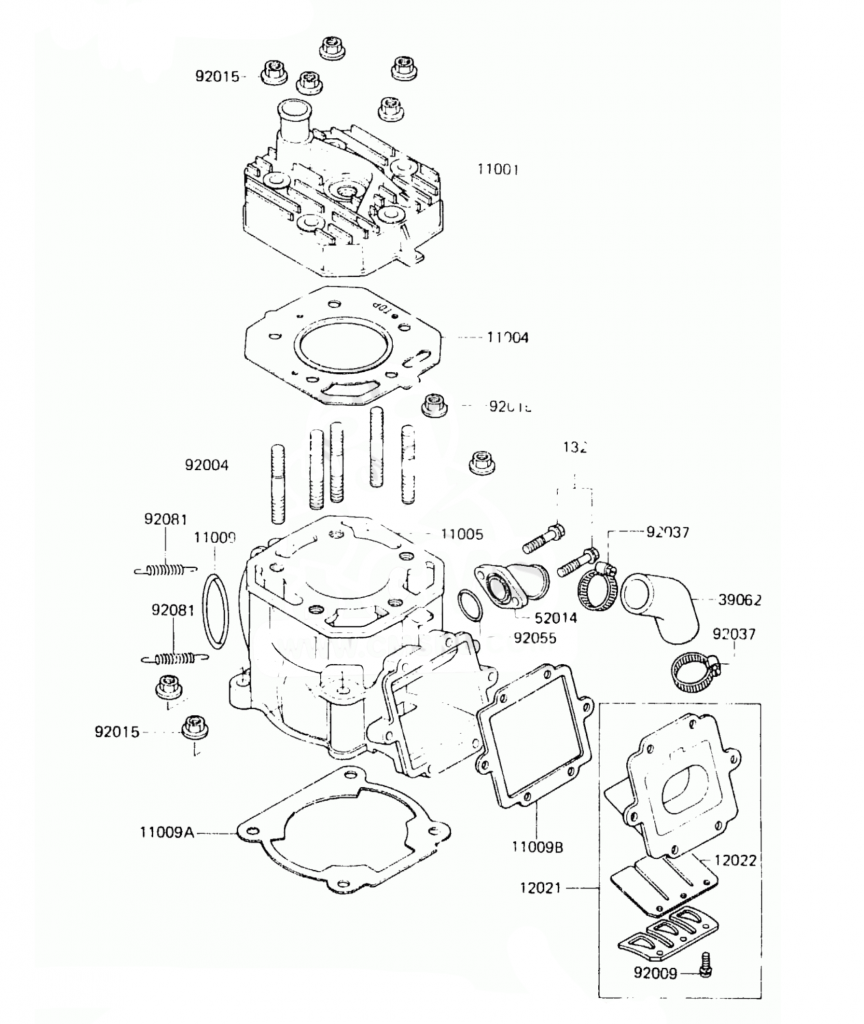

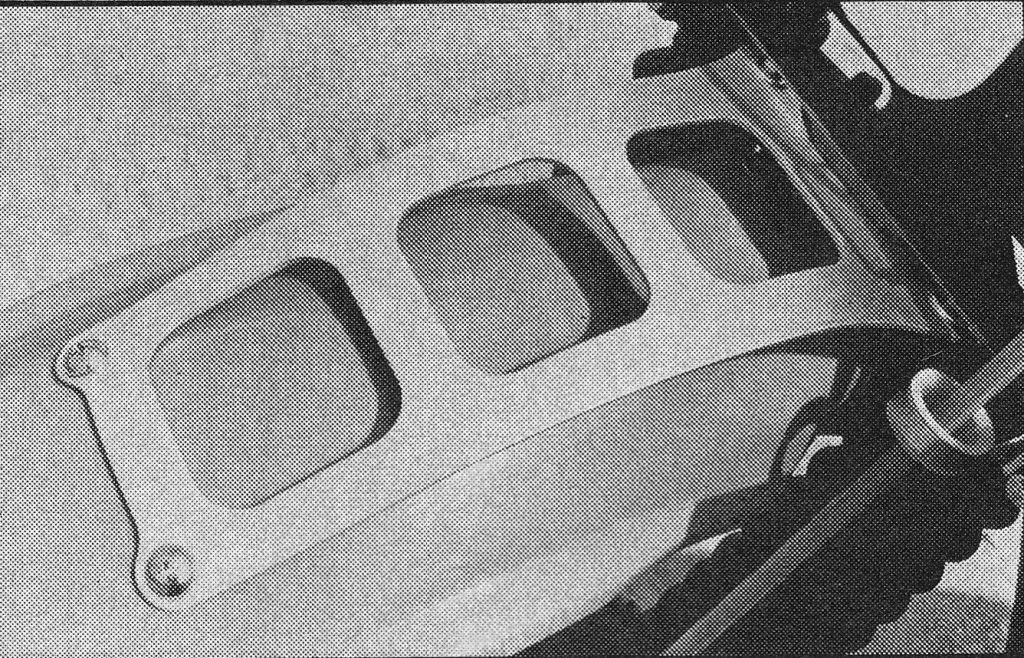

Without a power valve to service, top-end jobs on the KX125 were simpler than on the CR or YZ in 1984. While this was a bonus for mechanics, the KX’s lack of a boreable cylinder liner was a major bummer if it happened to suck dirt or stick a ring. Credit: Kawasaki

Without a power valve to service, top-end jobs on the KX125 were simpler than on the CR or YZ in 1984. While this was a bonus for mechanics, the KX’s lack of a boreable cylinder liner was a major bummer if it happened to suck dirt or stick a ring. Credit: Kawasaki

The forks were harsh and the styling of the machine was “unique” to say the least. In spite of these flaws, the KX did have its devotees due to its class-leading horsepower and sano front disc brake. Overall, it was a bike with a lot of power but very little polish.

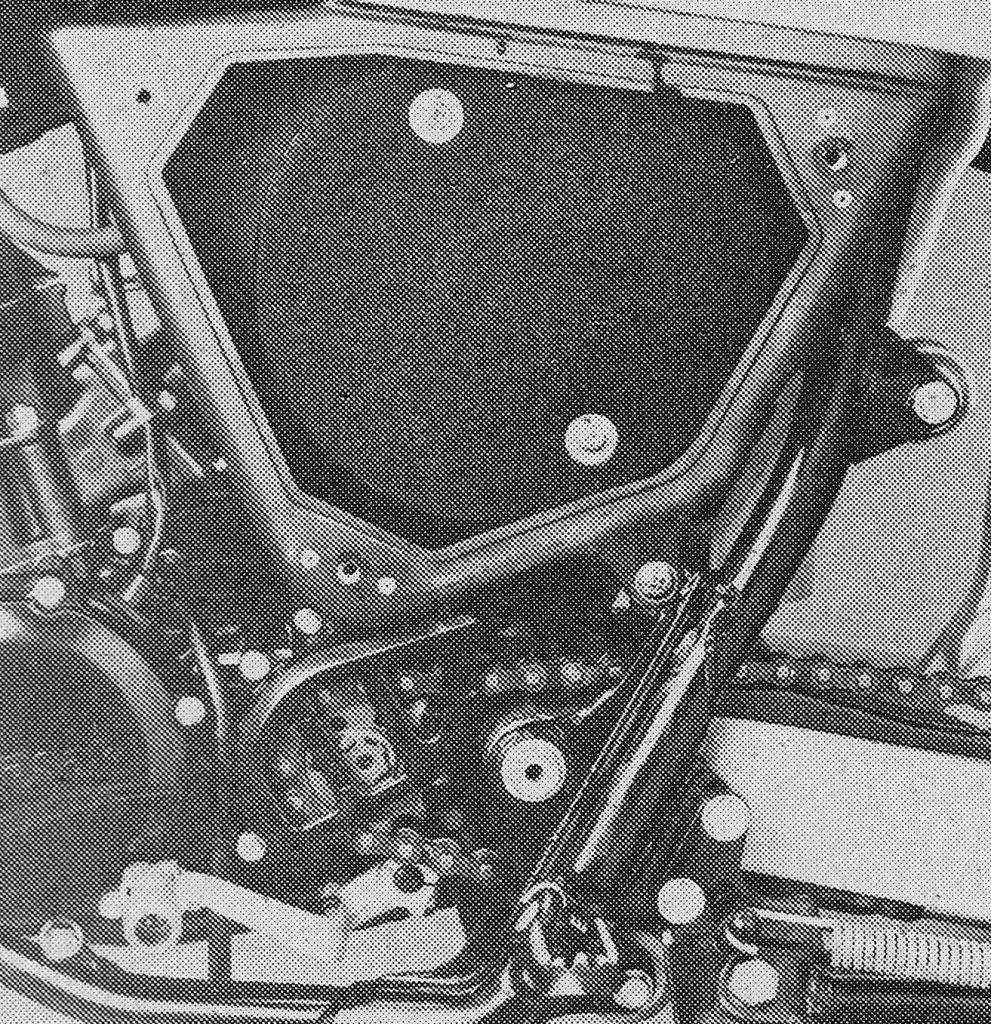

An all-new chassis for 1984 scaled down the ergonomics and tightened up the handing on Kawasaki’s 125 racer. Photo Credit: Cycle World

An all-new chassis for 1984 scaled down the ergonomics and tightened up the handing on Kawasaki’s 125 racer. Photo Credit: Cycle World

For 1984, Kawasaki looked to keep the two strong points of the ‘83 model and do away with literally everything else. In order to accomplish this, the designers threw away nearly everything from the ’83 machine and started from scratch with an all-new design based off of Jeff Ward’s 1983 SR125 works machine. The new chassis was of a completely new configuration and featured a slightly shorter wheelbase (.7 inches) and steeper steering head angle (27.5 degrees vs. 28 degrees) than 1983. Compared to the outgoing frame, the new chassis was lighter overall but stronger, due to the use of larger tubing in critical areas and increased gusseting at the swingarm pivot.

A redesigned airbox for 1984 flowed more air but sealed poorly. Care had to be taken to prevent dirt and debris from making its way past its porous side cover. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

A redesigned airbox for 1984 flowed more air but sealed poorly. Care had to be taken to prevent dirt and debris from making its way past its porous side cover. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

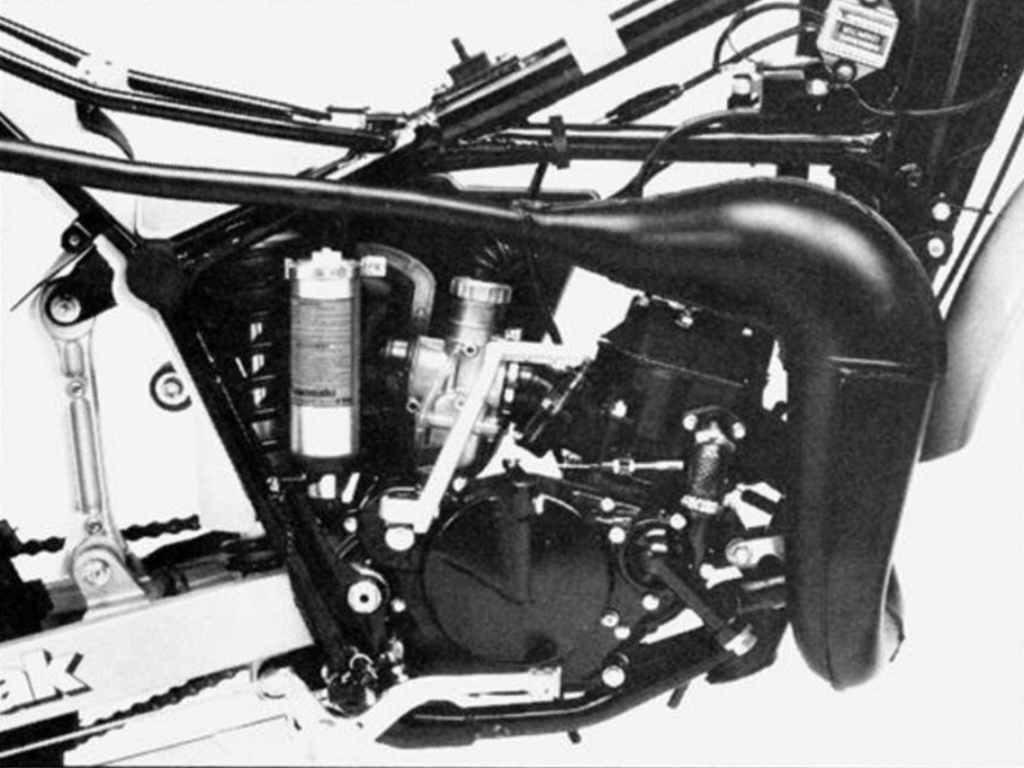

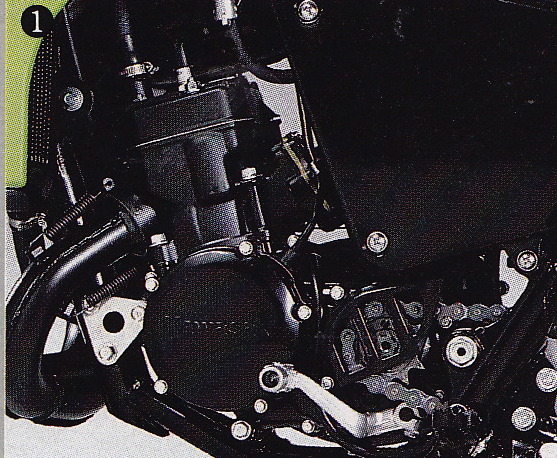

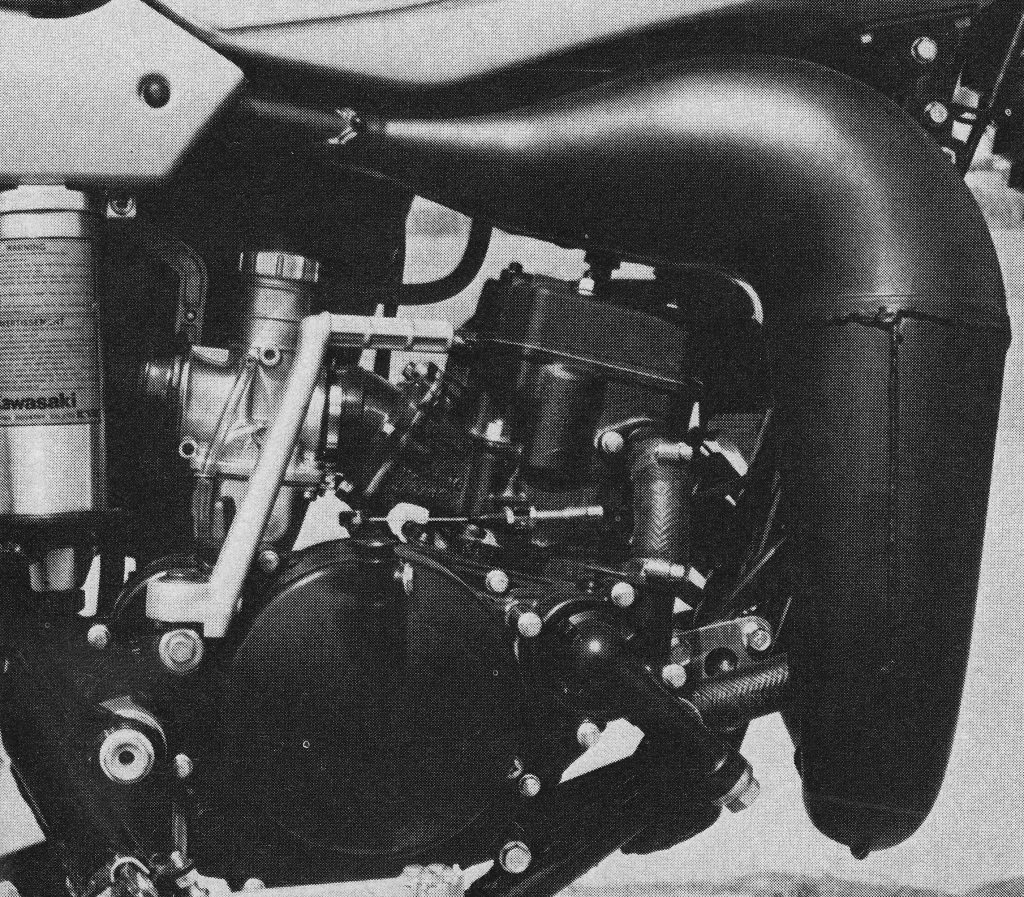

On the motor side, Kawasaki focused on increasing the torque of the motor and addressing the 1983’s woeful reliability. In order to do this, the engineers reinforced the cases and increased the surface mating area to prevent the chronic leaks of ’83. The transmission was also beefed up with new gears that featured wider teeth and improved heat-treating for increased durability. The clutch was also revised with new friction plates that incorporated radial grooves for better oil flow.

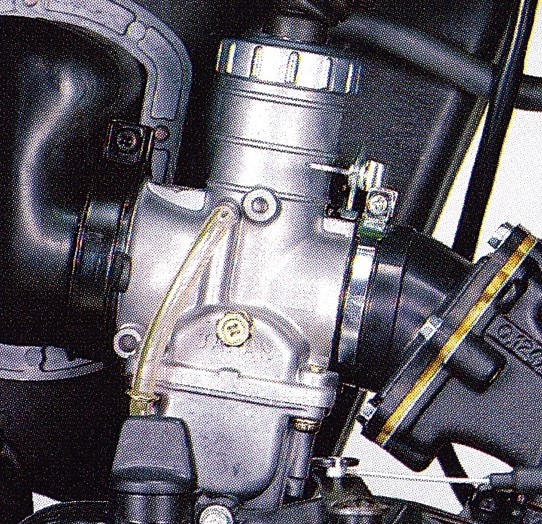

An all-new carburetor for 1984 did away with Kawasaki’s proprietary reverse-flow jets and added a unique flat-bottomed “R-slide” to reduce intake turbulence and improve low-end response. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

An all-new carburetor for 1984 did away with Kawasaki’s proprietary reverse-flow jets and added a unique flat-bottomed “R-slide” to reduce intake turbulence and improve low-end response. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In spite of its lack of a power valve, the KX125’s 124cc mill produced by far the broadest powerband in the class. From the first crack of the throttle until the cows came home, nothing else in ’84 was even close. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In spite of its lack of a power valve, the KX125’s 124cc mill produced by far the broadest powerband in the class. From the first crack of the throttle until the cows came home, nothing else in ’84 was even close. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the top end, the KX125 continued to use its exclusive Electrofusion (a technique that electrically bonds a .007-inch coating of molybdenum and steel to the aluminum cylinder liner for increased durability) process to line the cylinder and maintained the same 56.0 x 50.6 bore and stroke it had used 1983. Internally there was all-new porting, a lighter crank, and increased cooling capacity to keep temps under control. For 1984, all of the motor’s water passages were enlarged and a new longer radiator (still single-sided) was installed to help combat the overheating issues from the year before. In total, all of these changes added up to a whopping 29% increase in cooling capacity over 1983.

This original Uni-Trak linkage worked well enough at smoothing the track but demanded compromises in packaging and weight distribution that would eventually lead to its retirement in 1986. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

This original Uni-Trak linkage worked well enough at smoothing the track but demanded compromises in packaging and weight distribution that would eventually lead to its retirement in 1986. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The new porting specs for 1984 raised the exhaust port slightly and enlarged the transfers for additional flow. An all-new expansion chamber was also installed that was designed to work with the revised motor settings. Additional tuning was accomplished through the use of an all-new ignition that employed slightly less spark advance than ‘83. On the intake side, an all-new 34mm “oval-bore” Mikuni with a unique flat-bottomed “R-Slide” was installed and mated to a redesigned reed-valve that utilized high-tech carbon fiber pedals for increased response. Finishing off the new motor was a redesigned airbox that offered increased volume and easier access through a convenient side cover.

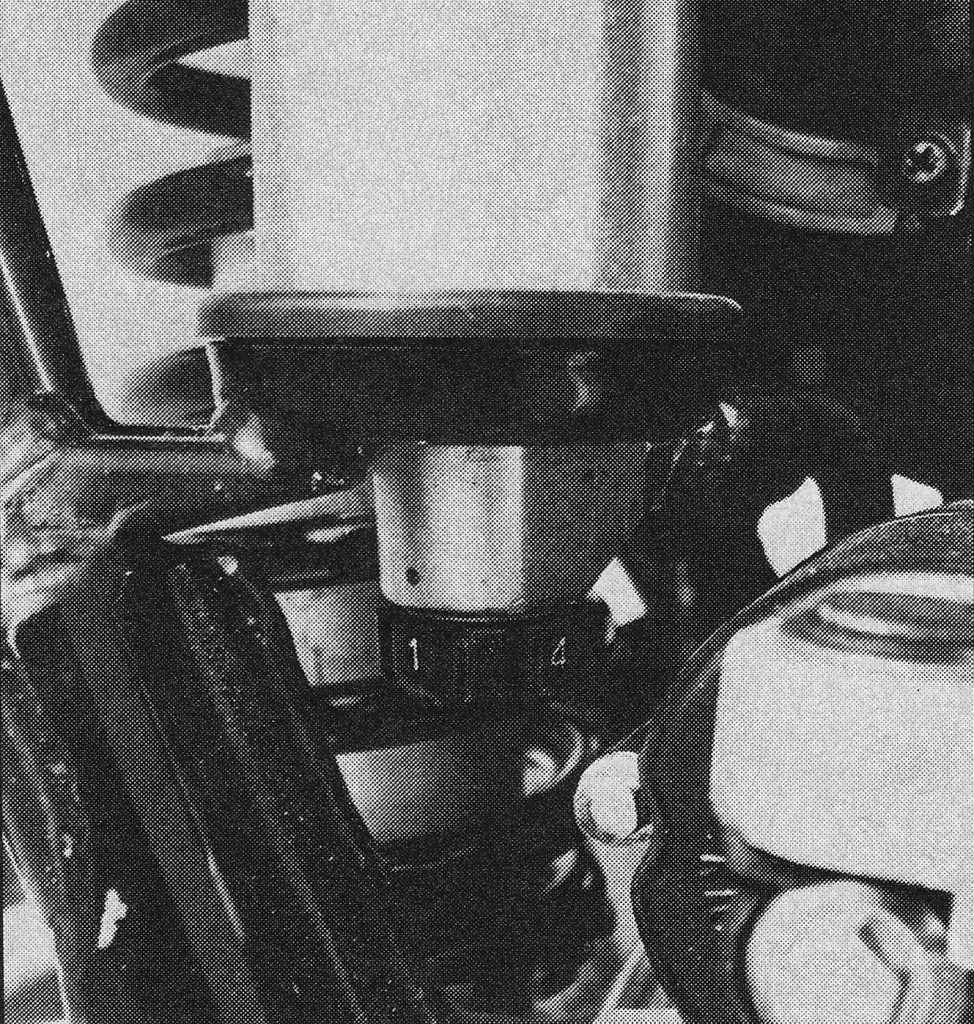

The KX’s KYB damper offered multiple adjustments for compression and rebound damping. While the compression setting was easily adjustable via this knob at the bottom of the remote reservoir, changing the rebound required removing several pieces of bodywork to access the adjuster. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

The KX’s KYB damper offered multiple adjustments for compression and rebound damping. While the compression setting was easily adjustable via this knob at the bottom of the remote reservoir, changing the rebound required removing several pieces of bodywork to access the adjuster. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

On the suspension end of things, the ’84 KX125 continued to use Kawasaki’s unique Uni-Trak rear linkage system. This configuration consisted of a large single damper attached by a set of cranks and levers that varied the forces exerted on the shock as it moved through its travel. For 1984, the Uni-Trak linkage was revised to offer slightly less progression and mated with a new aluminum-bodied Kayaba shock. Internally, the new shock discarded the DeCarbon system it had used in 1983 in favor of a new bladder design. This was done to reduce friction for improved fade resistance and smoother operation. The new shock also featured adjustments for both compression and rebound, an improvement over the rebound-only settings of ’83. In addition to offering improved cooling and greater adjustability, the revised shock featured slightly more travel (.4 inches) than 1983.

The new alloy fender brace on the KX125 was a very “Euro” touch in 1984. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

The new alloy fender brace on the KX125 was a very “Euro” touch in 1984. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Up front, the ’84 KX125 continued to use a set of 43mm conventional Kayaba forks offering 11.8 inches of travel. These forks were considered state of the art for the time with external adjustments available for compression and air pressure. Unlike modern forks, there was no adjustment for rebound. For 1984, new springs, revised damping, and a set of bottoming cones were the big changes on tap. All these changes were aimed at smoothing performance and reducing the metal-to-metal clank felt on hard hits.

Kawasaki made several updates in 1984 aimed at improving reliability on their 125 machine. Beefed-up center cases with larger mating surfaces looked to alleviate the chronic leaks of ’83, while a redesigned clutch and enlarged gears hoped to improve the longevity of the drive system. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Kawasaki made several updates in 1984 aimed at improving reliability on their 125 machine. Beefed-up center cases with larger mating surfaces looked to alleviate the chronic leaks of ’83, while a redesigned clutch and enlarged gears hoped to improve the longevity of the drive system. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Finishing off the changes for 1984 was all-new bodywork that took the KX125 from the ugly duckling of the 125 class to one of the belles of the ball. The new plastic ditched the oddball rear fender/number plate combo of 1982-1983 and replaced it with a far more conventional look that mimicked Jeff Ward’s 1983 SR125 works machine. Early plans actually had the KX adopting the orange seat Ward had used in select events in ’83 (Kawasaki’s corporate colors at the time were green and orange), but eventually Kawasaki settled on a more tasteful blue for the new saddle. The new seat was reshaped to make touching the ground easier for those with Jeff Ward’s inseam and featured an “up-the-tank” design for the first time to prevent inadvertent nut damage. The tank and shroud combo were also all-new and reshaped to be slimmer through the middle and less obtrusive when sliding forward for turns. Lastly, a new front fender was installed with a more rounded profile and a very “euro” alloy fender brace to help prevent the Kawasaki’s notoriously brittle green plastic from cracking when weighted down with mud.

Hung out in the breeze: While convenient, this extra-large water pump drain on the KX125 sure looked awfully vulnerable to crash damage. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Hung out in the breeze: While convenient, this extra-large water pump drain on the KX125 sure looked awfully vulnerable to crash damage. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the track, the new KX proved to be the powerhouse of the 1984 125 class. On the dyno, the new motor only produced a modest .3 horsepower increase over 1983, but that was only half the story. On the torque side of the equation, the figures were far more impressive. Compared to 1983, the new motor pumped out a remarkable 33% increase in torque and did it at 10% less rpm. Even more impressively, those figures were achieved without the benefit of any sort of “power valve.” By 1984, both the Yamaha and Honda 125s were employing variable exhaust gizmos in an effort to broaden the power of their small-bore racers, but neither could match the impressive output of the less-complicated KX125 mill.

The 43mm Kayaba front forks on the KX125 were the weakest link in an otherwise excellent motocross package. In stock condition they were too soft and underdamped for any serious motocross work. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The 43mm Kayaba front forks on the KX125 were the weakest link in an otherwise excellent motocross package. In stock condition they were too soft and underdamped for any serious motocross work. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the real world of berms and bumps, the KX125 held a huge advantage over its tiddler rivals. Compared to its competitors, the little green powerhouse felt more like a 150 than a standard 125. It started pulling earlier and with more authority than any of the other machines in its class. Out of turns, it could be rolled on without bogging and the slightest stab of the clutch rocketed it forward. In the midrange, it pulled hard enough that many magazines compared it with 250s from only a few years before. On the top end it was less impressive, but screaming it still yielded solid acceleration. As with 1983, the KX’s best work was done in the midrange where it hooked up and hauled harder than any other machine the class. Unlike ’83, however, the new motor was great for pros and novices alike. Its strong low-end pickup made keeping it on the pipe a breeze and its meaty midrange blast made throttle jockeys smile. In 1984, no other 125 could come close to the KX’s winning combination of power output, power placement, and overall ease of use.

The Uni-Trak rear suspension on the KX was not perfect but it worked far better than the marshmallow forks. There was a slight problem with fading once hot, but most of the time it performed well enough for the majority of riders likely to throw a leg over a 125. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The Uni-Trak rear suspension on the KX was not perfect but it worked far better than the marshmallow forks. There was a slight problem with fading once hot, but most of the time it performed well enough for the majority of riders likely to throw a leg over a 125. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Unfortunately, on the suspension end of things the picture was not quite as rosy. The new 43mm KYB forks were slightly better for 1984, but still nowhere close to the top of the 125 standings. In spite of slightly stiffer springs for ‘84, they still felt far too soft and underdamped for anyone above an absolute novice. Even with lighter riders aboard, they dove under braking and wallowed in the rough. Large jumps sent them crashing to the stops and more than a few riders complained of a harsh spike in the mid-stroke. Overall, it was ranked the worst-performing front end of the 1984 125 class.

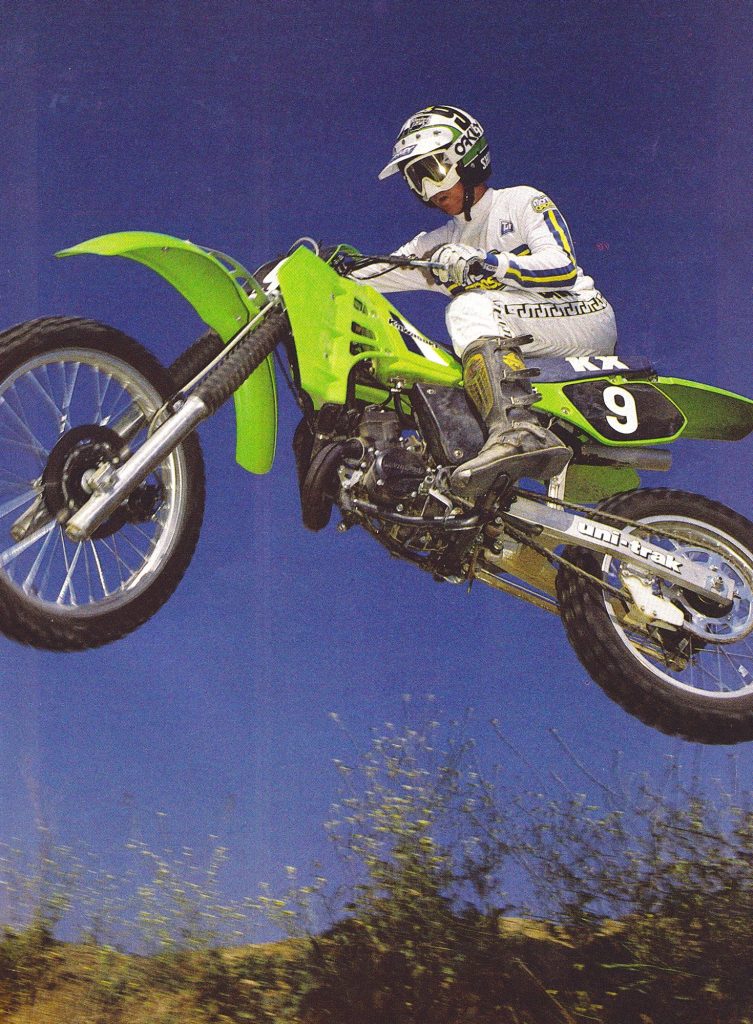

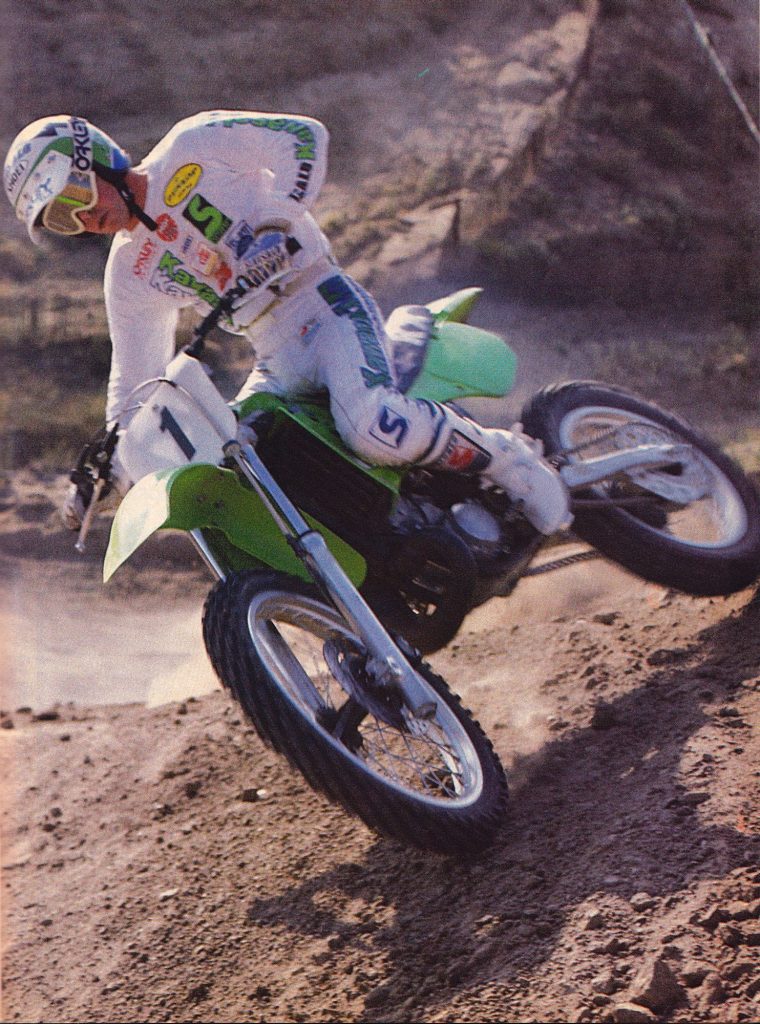

The KX had the power and handling for big air in 1984, but its forks were likely to give you a pair of sore wrists once you came back down to Earth. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The KX had the power and handling for big air in 1984, but its forks were likely to give you a pair of sore wrists once you came back down to Earth. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the rear, the performance picture was significantly better. The Uni-Trak shock worked well and was adjustable enough to suit riders of many skill levels. The new bladder design provided smooth action, but fading continued to be an issue. When fresh, it provided the second-best performance in the class, behind only the Suzuki’s Full Floater. Once it got hot though, that performance began to deteriorate quickly. Amateurs that ran short motos and failed to really press its performance were unlikely to notice, but fast guys commented on its deteriorating performance.

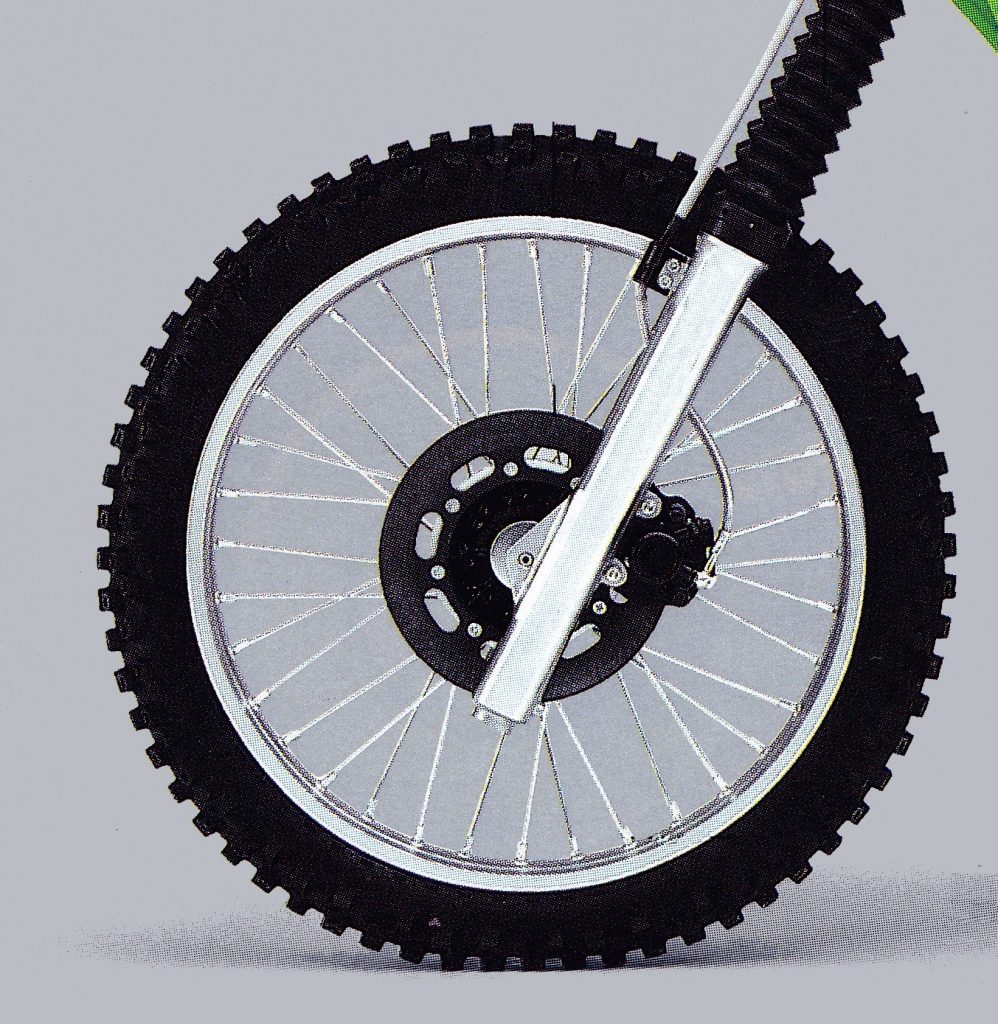

The KX’s front disc provided strong but inconsistent performance. Leaks and chronic air buildup in the system prevented it from besting Honda’s trouble-free new Nissin stopper in the final standings. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The KX’s front disc provided strong but inconsistent performance. Leaks and chronic air buildup in the system prevented it from besting Honda’s trouble-free new Nissin stopper in the final standings. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

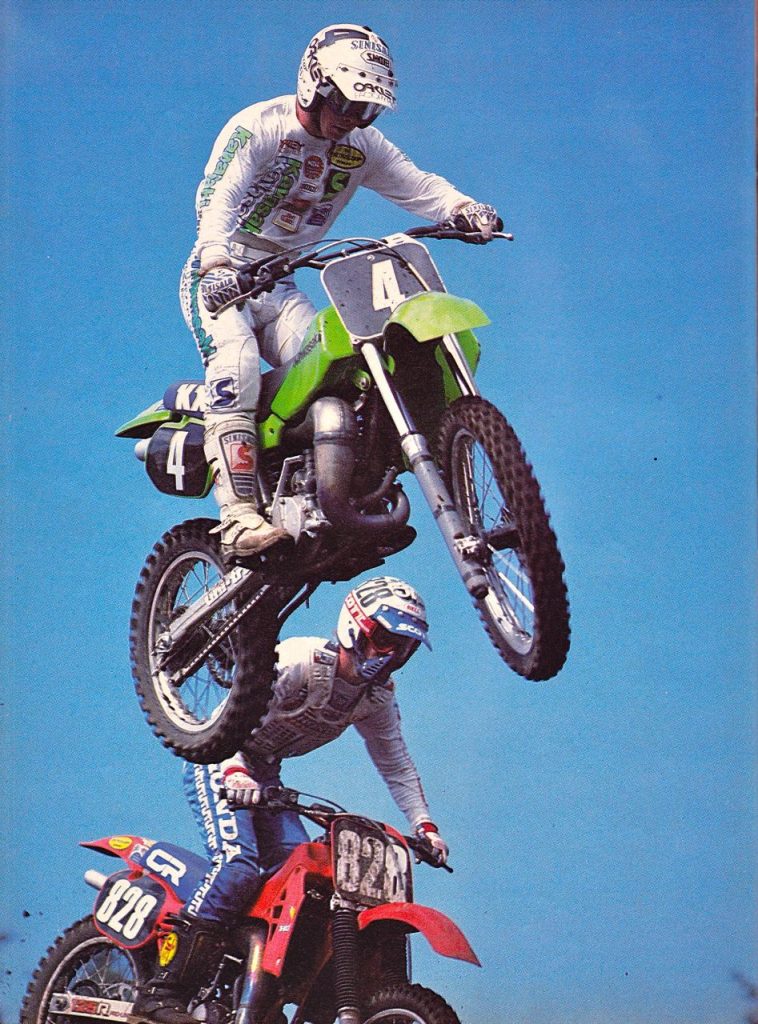

Jeff Ward took a works version of the new KX125 to his first 125 National Motocross title in 1984. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Jeff Ward took a works version of the new KX125 to his first 125 National Motocross title in 1984. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the handling front the new KX was handicapped quite a bit by its subpar fork performance. In the turns, they dove and caused the front end to knife and tuck under. At speed, they hung down and made the bike feel twitchy and unbalanced. If you sorted out the forks and could get the bike leveled it actually handled pretty well overall. It was never going to turn as sharply as the Honda CR125R, but neither was it going to rip your hands off the bars when coming down from speed. Overall, it was a workmanlike handler that got the job done with competence instead of finesse.

Drum rear brakes were still de rigueur in 1984 and the KX125 offered one of best rear binders in the class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Drum rear brakes were still de rigueur in 1984 and the KX125 offered one of best rear binders in the class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

When Jeff Ward rode MOTOcross magazine’s test bike he stated that the stock KX’s power and handling were not very far off of his works bike, but the suspension was considerably softer. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

When Jeff Ward rode MOTOcross magazine’s test bike he stated that the stock KX’s power and handling were not very far off of his works bike, but the suspension was considerably softer. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

On the detailing side of things, the KX125 was improved for 1984, but still plagued with a few long-standing Kawasaki issues. The excellent front disc binder was super powerful, but prone to leaks and perpetually in need of bleeding. Nearly every bolt and nut continued to be of poor quality and care had to be taken not to strip or break fasteners when tightening or loosening them. Frame cracking was common on hard-ridden machines and the top Uni-Trak strut mount was a point of failure on many KXs. The plastic looked good but continued to be more brittle than the competition. Dropping it on the radiator side was a sure recipe for a cracked shroud (at lease there was only one to break), but at least the aluminum brace kept the front fender from going AWOL in deep mud. The redesigned airbox made servicing easier, but the new cover did a poor job of keeping out dirt, dust, and general track detritus. The filter was also of dubious quality and lasted about three washings before it started coming apart at the seams. If, by chance, you missed this development and allowed some dirt into the motor, you were also in for an expensive repair due to the Kawasaki’s non-boreable Electrofusion cylinder.

Handling on the ’84 KX125 was far better than previous Kawasaki efforts once you got the suspension dialed in. With the forks brought up to snuff the new chassis turned well and was decently stable at speed. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

Handling on the ’84 KX125 was far better than previous Kawasaki efforts once you got the suspension dialed in. With the forks brought up to snuff the new chassis turned well and was decently stable at speed. Photo Credit: MOTOcross

While all of this may sound like a litany of issues, it was actually pretty much par for the course in 1984. Even the best machines of the time had design and reliability issues that required watching and addressing. Buyers in 1984 knew this and were willing to accept problems that would send modern riders to social media in search of someone to flame. No bike in 1984 was perfect and the KX125 was certainly better than some, and no worse than most others.

The 1984 KX125 stands as one of Kawasaki’s most successful models of the 1980s. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The 1984 KX125 stands as one of Kawasaki’s most successful models of the 1980s. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In the end, the new KX125 proved to be the class of the 1984 125 field in spite of its deficiencies. While its poor forks and middle-of-the-road handling were setbacks, they were not nearly enough to derail an otherwise solid package. The new motor was more reliable (no more overheating and much fewer air leaks), more powerful, and even easier to ride. It was an unbeatable combination than propelled the green machine to the top of the standings. There were bikes that handled better (Honda) and bikes with better suspension (Suzuki), but no other machines had it covered where it mattered most. In the 125 class power is king, and in 1984, that made the KX125 the ruler of the roost.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com