For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Suzuki’s boldly-styled RM125 for 1991.

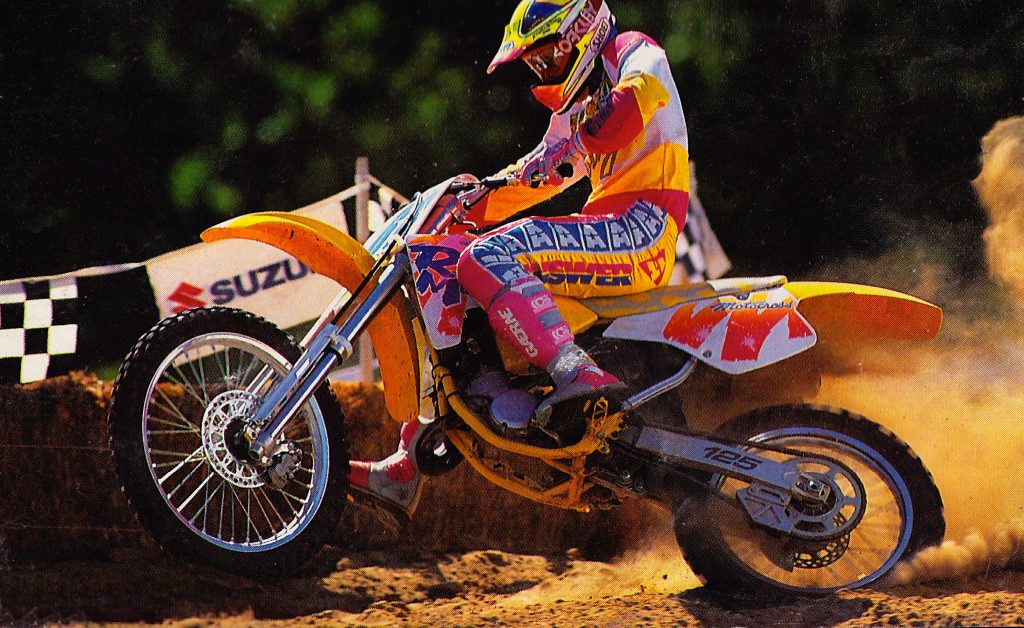

In 1991 Suzuki revamped the look of their entire lineup with a fresh color pallet and a set of very bold new graphics. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1991 Suzuki revamped the look of their entire lineup with a fresh color pallet and a set of very bold new graphics. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Once upon a time, Suzuki was the preeminent power in 125 motocross racing. Throughout the seventies and early eighties, no brand in motocross was as successful in the tiddler division as the guys from Hamamatsu. Yellow machines dominated the shootout standings and captured a run of ten straight 125 World Motocross Championships from 1975-1985. On the track, the RM125 was the choice of novices and pros alike and easily the most successful machine in motocross over that decade.

After the clean and understated look of the 1990 machine, the outlandish appearance of the 1991 RM125 came as a shock to many. Aside from the Mardi Gras attire, however, the two machines were far more similar than they were different. Photo Credit: Suzuki

After the clean and understated look of the 1990 machine, the outlandish appearance of the 1991 RM125 came as a shock to many. Aside from the Mardi Gras attire, however, the two machines were far more similar than they were different. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Starting in the mid-eighties, however, the fortunes of Suzuki’s all-star started to falter. Sub-par power plants, old-fashioned styling, and poor reliability torpedoed the reputation of the once-dominant RM125. As Honda’s motocross stock ascended, Suzuki’s declined, and by 1988, they were at the back of a very competitive 125 field.

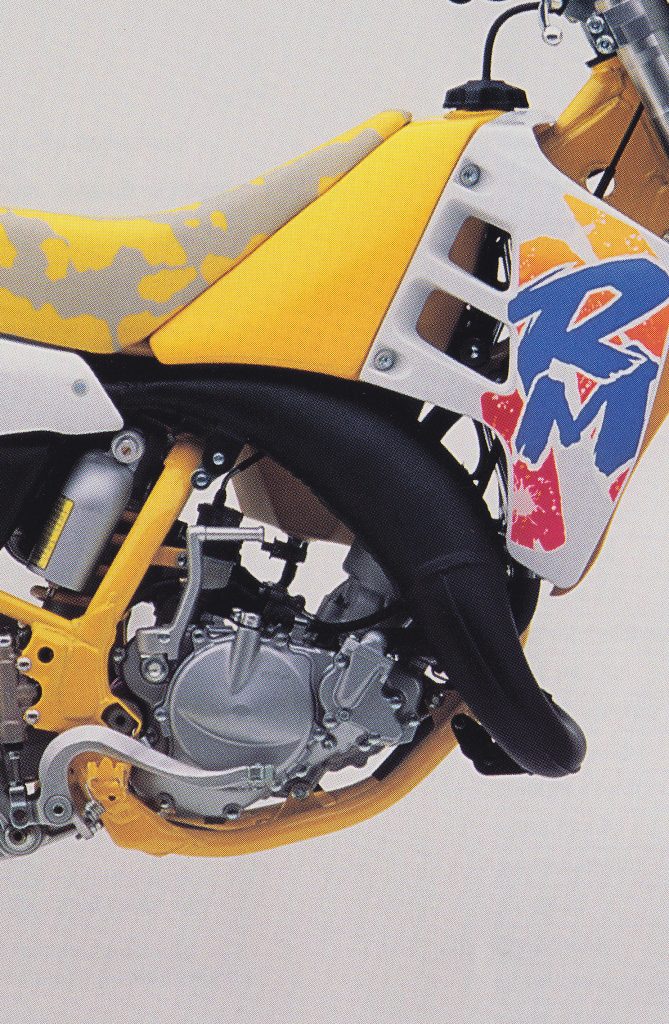

Boostless: One of the big changes for 1991 on the RM125 was supposed to be a set of new “boost ports” built into the cylinder to broaden the machine’s slightly narrow power. While early literature and press information touted the arrival of these tricks taken from Guy Cooper’s works bike, the production team back in Japan did not get the memo. Once tuners cracked into the production machines they found the ports had been deleted at some point before production. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Boostless: One of the big changes for 1991 on the RM125 was supposed to be a set of new “boost ports” built into the cylinder to broaden the machine’s slightly narrow power. While early literature and press information touted the arrival of these tricks taken from Guy Cooper’s works bike, the production team back in Japan did not get the memo. Once tuners cracked into the production machines they found the ports had been deleted at some point before production. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1989, Suzuki looked to right their 125 motocross ship by introducing an all-new RM125. Redesigned and reimagined from the ground up, the ’89 RM125 cast aside the stodgy styling and gutless powerband of ’88 in favor of sexy new bodywork and a punchy new case-reed motor. The redesigned RM offered razor-sharp turning and excellent suspension performance, but it lacked the high-rpm pull offered by Honda’s CR125R. Overall, it was a huge improvement over recent Suzuki offerings but not enough to reclaim the top spot in the 125 division.

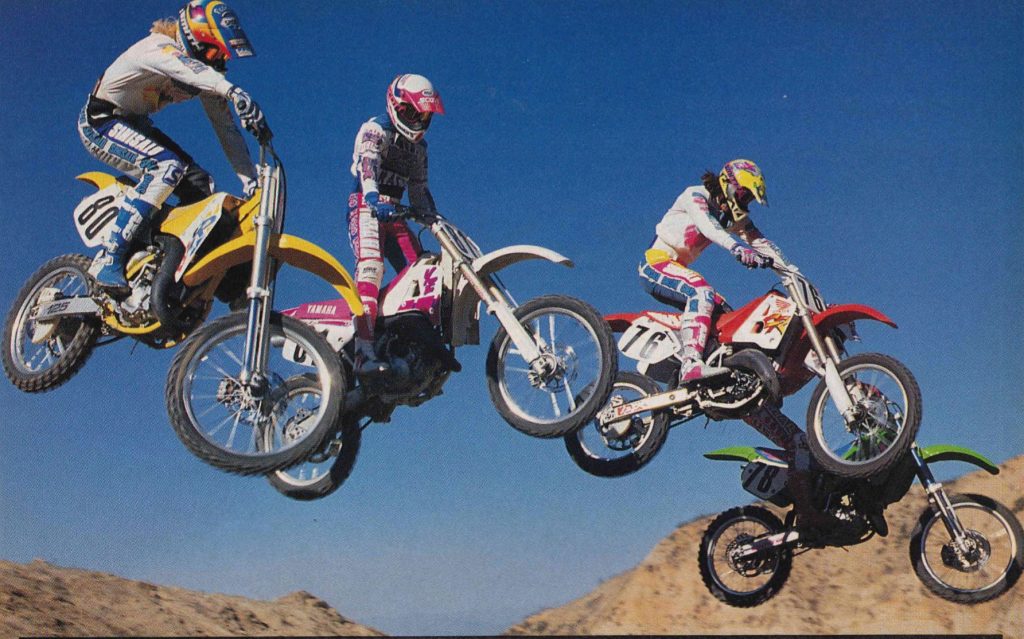

The Red Ripper: In 1991, very few machines could run with Honda’s CR125R. What the red machine accomplished with lots of revs and a long pull, the RM achieved with a quick pickup and hard midrange blast. On tight tracks, the RM had a distinct advantage and it was far easier to keep on the pipe between gears than the red machine. Open things up, however, and the competition was likely to be stuck sucking on the CR’s vapor trail. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The Red Ripper: In 1991, very few machines could run with Honda’s CR125R. What the red machine accomplished with lots of revs and a long pull, the RM achieved with a quick pickup and hard midrange blast. On tight tracks, the RM had a distinct advantage and it was far easier to keep on the pipe between gears than the red machine. Open things up, however, and the competition was likely to be stuck sucking on the CR’s vapor trail. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

For 1990, the RM125 was back with a new set of inverted forks and some minor motor mods aimed at broadening its narrow power spread. The bike was still drop-dead gorgeous and popular with pros due to Suzuki’s generous contingency program, but the 1990 model did not offer much of a different experience than the fun but not particularly fast ’89 RM. For Supercross, the bike was excellent with its precise turning and quick-building power. Out of turns, the RM was super responsive and very quick, but once the track opened up its lack of stability and high-rpm power became a hindrance. It was quick, fun, and well suspended, but once again overshadowed by the more potent machines from Kawasaki and Honda.

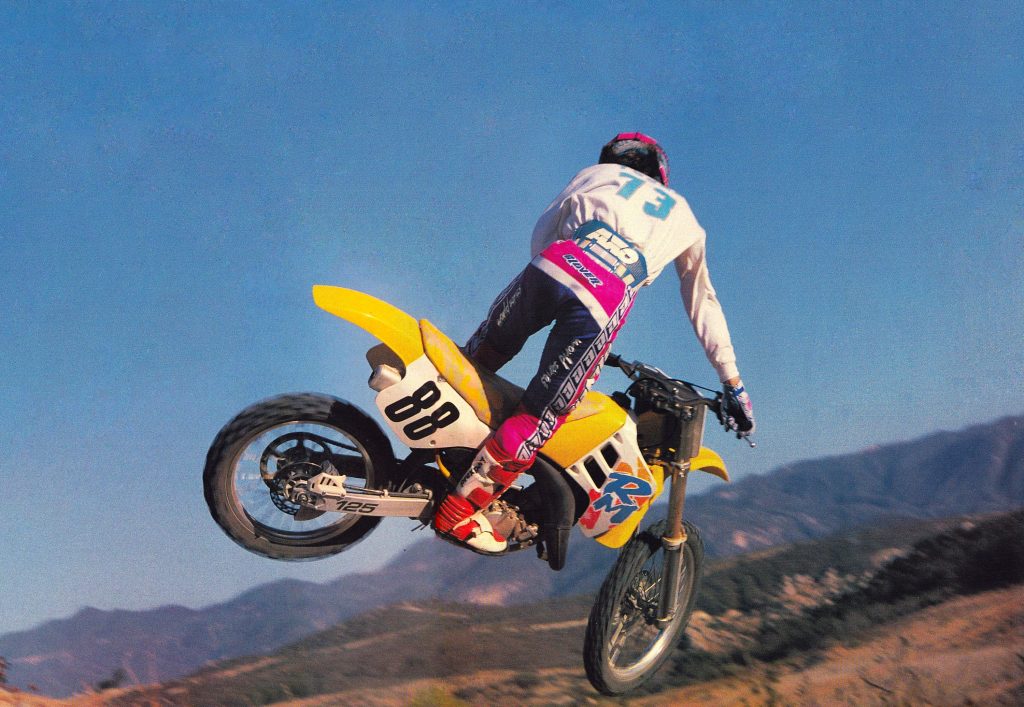

While American Suzuki chose to deck their 1991 machines out with white plastic, RMs bound for other markets maintained the 1990’s more monochromatic appearance. While it is debatable which color scheme looked better, there is no doubt that both were a radical departure for the previously conservative brand. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While American Suzuki chose to deck their 1991 machines out with white plastic, RMs bound for other markets maintained the 1990’s more monochromatic appearance. While it is debatable which color scheme looked better, there is no doubt that both were a radical departure for the previously conservative brand. Photo Credit: Suzuki

After two years of offering almost-good-enough RMs, Suzuki came into 1991 with a plan to finally take back the crown of the top 125 in the land. To do that, the engineers looked to build on the things that people already loved about the current machine. On that balance sheet were the RM’s super-responsive motor, ultra-sharp turning, and excellent suspension.

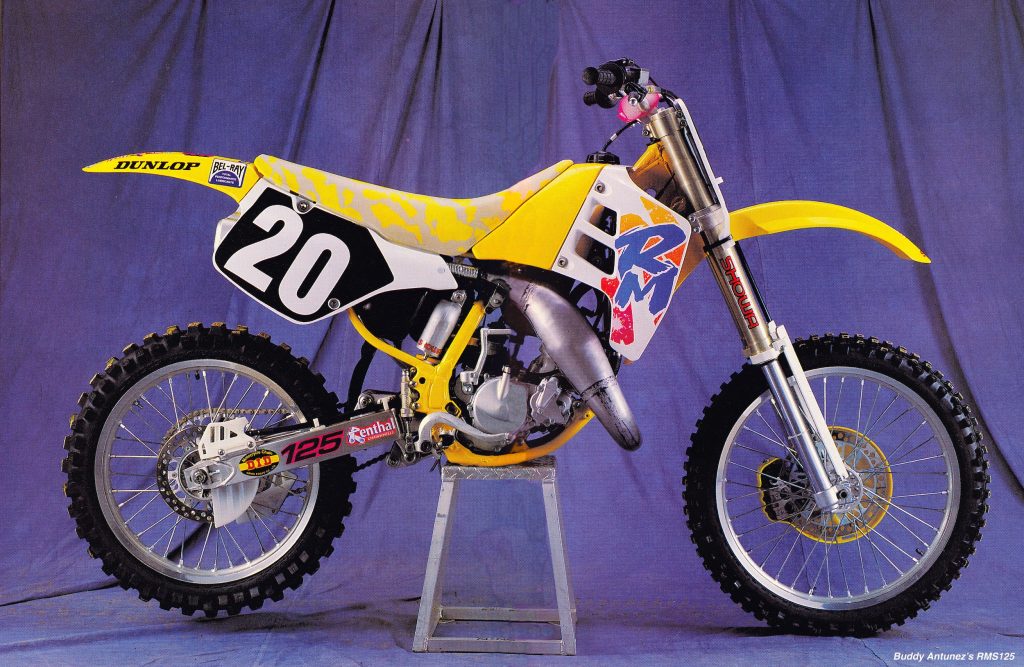

In 1991, Buddy Antunez was still considered one of Suzuki’s rising stars in the 125 class. A huge mini star in the late eighties on the powerful R&D Suzuki team, Antunez had come into the class in 1989 with a ton of fanfare and much expectation. Unfortunately for Buddy, the 1991 season would turn out to be a major disappointment with a pair of tenth-place finishes indoors and out. At the end of the season, Antunez would be released by Suzuki and move over to the Peak Honda squad to be Jeremy McGrath’s teammate for 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

In 1991, Buddy Antunez was still considered one of Suzuki’s rising stars in the 125 class. A huge mini star in the late eighties on the powerful R&D Suzuki team, Antunez had come into the class in 1989 with a ton of fanfare and much expectation. Unfortunately for Buddy, the 1991 season would turn out to be a major disappointment with a pair of tenth-place finishes indoors and out. At the end of the season, Antunez would be released by Suzuki and move over to the Peak Honda squad to be Jeremy McGrath’s teammate for 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

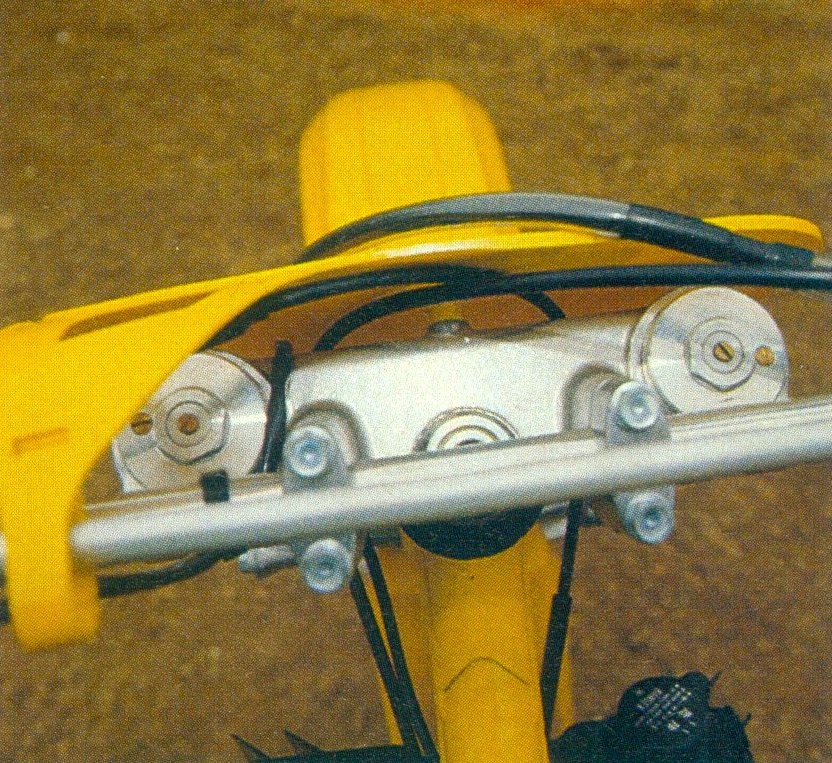

To accommodate the added stresses of the RM’s new larger forks both the steering stem and frame down tube were beefed up for 1991. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

To accommodate the added stresses of the RM’s new larger forks both the steering stem and frame down tube were beefed up for 1991. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

The two previous years, riders had loved the RM’s instant power, but fast guys lamented its relatively short pull. To address this, the engineers spec’d an all-new cylinder that featured reconfigured porting and a repositioned Automatic Exhaust Tuning Control (AETC) valve. In addition to these changes, the RM was also slated to receive a set of new exhaust “boost ports” for 1991. These small ports had been a trick of savvy tuners for years and were found on machines like Guy Cooper’s 1990 125 National title-winning RM125. Early press releases touted the benefits of these new ports and all of the launch literature given to the magazines extolled their virtues. Oddly, however, once the production RM125s made their way to dealers, the ports were missing. When Motocross Action asked American Suzuki’s PR department about the missing ports at the time, they seemed to be just as surprised as the magazines that they were not there. Apparently, someone in Japan had deleted the additional exhaust scavengers at the last minute and neglected to tell their partners they were AWOL for ’91.

All-new 45mm Showa forks for 1991 offered adjustable compression and rebound settings, a feature the Hondas of the time lacked. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

All-new 45mm Showa forks for 1991 offered adjustable compression and rebound settings, a feature the Hondas of the time lacked. Photo Credit: Moto Revue

Aside from the magic vanishing exhaust ports, the rest of the motor changes for 1991 were very straightforward. A new head repositioned the water spigot rearward to keep it away from the hot exhaust port and a new water pump and redesigned cooling system offered improved performance by circulating the motor’s coolant through both radiators simultaneously. To improve durability, a new piston was spec’d for 1991 with a 7% higher concentration of silicone in its construction. The transmission was also beefed up for 1991 with third, fourth, fifth, and sixth gears getting the Schwarzenegger treatment. On the intake side, the RM retained the case-reed arrangement it had employed since 1989 and mated that to Mikuni’s 35mm “Slingshot” smooth-bore carburetor. While the Slingshot carb did not seem to garner much fanfare in the U.S. it featured prominently in other markets where the name “Slingshot” replaced “Motocross” in the RM’s new graphics. Finishing off the motor package was a redesigned pipe and a new silencer that was lighter and shorter for 1991.

In 1986, Bob Hannah made the jump from Honda to Suzuki in an effort to get the yellow machines back on track. While it took several years to get the RM125 back to its former glory, the machines steadily improved under his testing influence. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1986, Bob Hannah made the jump from Honda to Suzuki in an effort to get the yellow machines back on track. While it took several years to get the RM125 back to its former glory, the machines steadily improved under his testing influence. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the chassis side, the RM received a more extensive overhaul for 1991. After using Kayaba components to great success for several years, Suzuki made the bold choice to switch to Showa for 1991. At the time this was a surprising move as Kayaba had been consistently outperforming its rival since the move to inverted forks in 1989. Honda’s Showa components were notorious for their poor performance and adopting a version of them on the RM seemed like a risky move. While the new 45mm Showa forks employed on the 1991 RM were the same size as the units found on the CR, they differed in their internal construction. Unlike the Honda versions, the new Suzuki Showas featured both compression and rebound adjustability and special low-friction seals and bushings to smooth performance.

A new swingarm, upgraded bearings, and all-new Showa shock highlighted the RM’s rear suspension news for 1991. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A new swingarm, upgraded bearings, and all-new Showa shock highlighted the RM’s rear suspension news for 1991. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the rear, the ’91 RM featured an all-new Showa damper with 40% more volume than 1990. This was done to improve fade resistance and ensure more consistent action throughout the moto. The new damper offered 12.8 inches of travel and adjustments for compression and rebound dampening. In addition to the new shock, the 1991 RM received a revised swingarm that was lighter and stronger, with new bearings for the Full Floater linkage that promised smoother action.

In 1991, nothing in the 125 class was as razor-sharp in the turns as the RM125. With a talented rider like Shane Trittler aboard the RM was capable of going over, under, or around the red, white and green competition. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1991, nothing in the 125 class was as razor-sharp in the turns as the RM125. With a talented rider like Shane Trittler aboard the RM was capable of going over, under, or around the red, white and green competition. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

To better work with the new larger forks, Suzuki’s engineers made a few significant changes to the RM’s frame for 1991. The frame downtube was strengthened by switching from round to boxed-section tubing and the overall geometry was altered slightly by pulling in the rake from 28 degrees to 27.45. The trail was decreased by 5mm and the fork’s offset was reduced by 2.5mm to further increase steering precision. In addition to the stronger frame, the new chassis featured a set of beefed-up steering head bearings to handle the loads imposed by the stiffer front forks. To increase rider comfort, footpeg width was increased by 10mm, and a new grippier seat cover was added to help keep the pilot in place under hard acceleration.

While hardcore racers found Suzuki’s decision to plaster graphics across the side plates head-scratching, the fact of the matter was most RMs probably never actually found their way to a race track and may have lived on many years with their brushstrokes intact. One interesting side note on these graphics is the subtle difference between the US and non-US versions. Here in the states (bottom), ours all said “Motocross” on the plates, but in other markets (top) the graphic featured “Slingshot” instead. This was a reference to the RM’s Mikuni Slingshot carburetor. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While hardcore racers found Suzuki’s decision to plaster graphics across the side plates head-scratching, the fact of the matter was most RMs probably never actually found their way to a race track and may have lived on many years with their brushstrokes intact. One interesting side note on these graphics is the subtle difference between the US and non-US versions. Here in the states (bottom), ours all said “Motocross” on the plates, but in other markets (top) the graphic featured “Slingshot” instead. This was a reference to the RM’s Mikuni Slingshot carburetor. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the bodywork side, the new RM featured the same basic components as 1990 but a swap in color pallet gave it a very different appearance for 1991. In 1990, the RM featured a simple and classy blue and yellow color scheme that was popular with riders and magazine editors alike. In use since 1984, this color combo had become a staple of the mid-to-late-eighties Suzuki design. For 1991, Suzuki made the bold move to ditch this iconic look in favor of a far more outlandish appearance.

Air Coop: In 1990, Guy Cooper took the RM125 to its first motocross title since the days of Mark Barnett in the early 1980s. In 1991, he was back and once again engaged in an epic duel with 1989 champ Mike Kiedrowski. Unfortunately for Coop, this time the MX Kied would come out on top delivering Kawasaki its first 125 National Motocross crown since Jeff Ward in 1984. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Air Coop: In 1990, Guy Cooper took the RM125 to its first motocross title since the days of Mark Barnett in the early 1980s. In 1991, he was back and once again engaged in an epic duel with 1989 champ Mike Kiedrowski. Unfortunately for Coop, this time the MX Kied would come out on top delivering Kawasaki its first 125 National Motocross crown since Jeff Ward in 1984. Photo Credit: Suzuki

At the time, Motocross was in a bit of a styling transition as the crazy and colorful designs common to the gear industry began to make their way to the bikes as well. For Suzuki, this meant a dramatic shift in the look of all of their machines for 1991. The new-look RMs dropped the iconic blue frame and all-yellow bodywork of ’90 in favor of a new white, orange, yellow, and gray patchwork of hues that was distinctive but less cohesive than the year before.

Originally introduced in 1989, the RM’s 125cc case-reed power plant was thoroughly modern but not jaw-droppingly powerful. Its best traits were its snappy delivery and strong midrange, which helped the bike get out of corners quickly and over obstacles easily. While riders accustomed to the Honda’s long and strong pull found it lacking, most testers liked its fun and easy-to-use powerband. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Originally introduced in 1989, the RM’s 125cc case-reed power plant was thoroughly modern but not jaw-droppingly powerful. Its best traits were its snappy delivery and strong midrange, which helped the bike get out of corners quickly and over obstacles easily. While riders accustomed to the Honda’s long and strong pull found it lacking, most testers liked its fun and easy-to-use powerband. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The new RM look certainly made the bike stand out in the showroom, but many found its cartoony appearance out of place on a serious racing machine. The odd splattered yellow and gray seat cover and giant brushstroke graphics looked more like a kindergarten art project than anything turned out by a professional design studio. The seat’s appearance was probably influenced by the popular Ceet Racing patterned designs of the time and the switch to white for much of the bodywork was most likely an attempt to make the RMs stand out more on TV where the sport was finally gaining some mainstream exposure through ESPN. Love it or hate it, there was no denying the interest the new look generated when Suzuki debuted it at the final round of the 1990 AMA Supercross season. Despite being largely a carry-over design, the ’91 RM125 looked completely new and that was certainly part of the calculus that went into the radical shift in appearance.

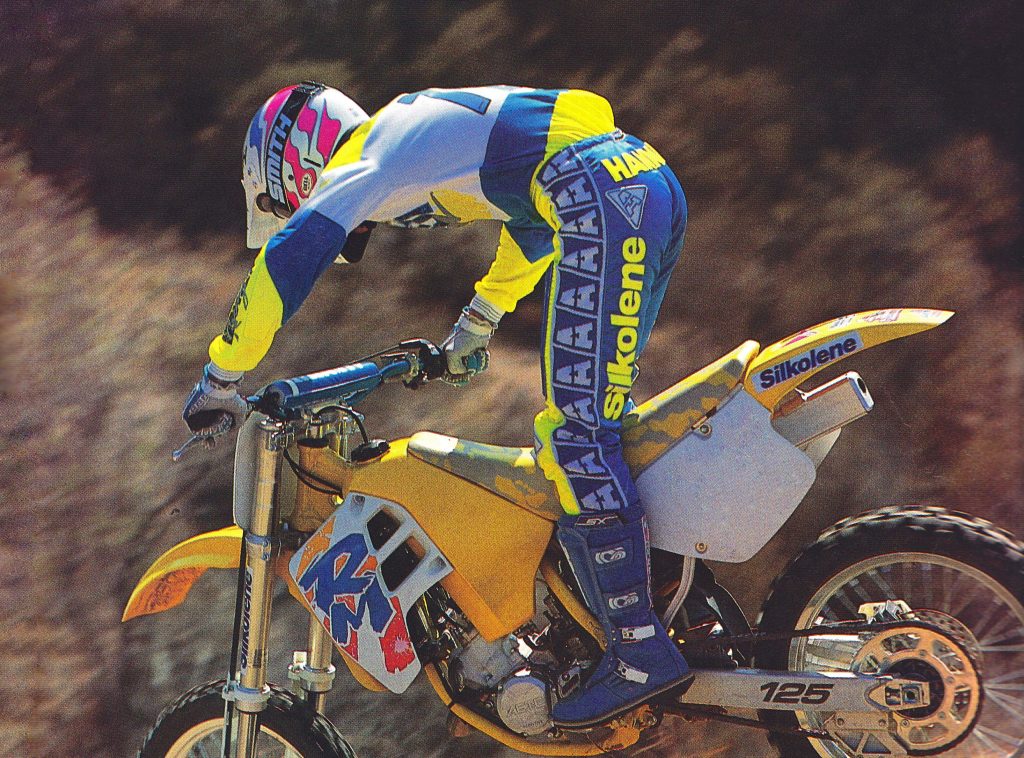

With its strong low-end response and quick-building power the RM tended to loft the front end out of turns. Here Buddy Antunez demonstrates the proper technique for putting power to the ground on the screaming yellow zonker. Photo Credit: Suzuki

With its strong low-end response and quick-building power the RM tended to loft the front end out of turns. Here Buddy Antunez demonstrates the proper technique for putting power to the ground on the screaming yellow zonker. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While the RM125s appearance was drastically changed for 1991, its basic DNA remained largely unaltered. Without the benefits of the boost ports, it ran nearly identically to the year before. That meant a strong low-to-mid hit with lots of quick-building power but not much rev. It snapped to life very early for a 125 and climbed on the pipe far sooner than revvers like the CR125R. The power was super responsive, and the bike could be ridden without frying the clutch plates out of every corner. This made the RM easy to ride and very novice-friendly but limited its appeal to more experienced 125 pilots. As in the past, the RM would happily rev if pushed, but the power tapered off appreciably past the midrange. Because of this, it was necessary to shift quite often to keep the RM in its relatively narrow sweet spot. Thankfully, the RM’s transmission and clutch were excellent and far more willing participants than much of the competition. While the RM’s powerband was not as long-pulling as the ones found on the Kawasaki and Honda, many riders picked it as the best overall motor package available in 1991. It was snappy, quick, and responded very well to easy power upgrades like pipes and reed-valves. As long as you did not try to wring it to the stops, it was super fun and very effective.

In 1991, Suzuki made the interesting choice to move away from long-time partner Kayaba in favor of Showa hardware. At the time, Showa had come under much fire for their poor performance on Honda’s machines, but these new 45mm units broke that tradition by actually offering winning performance on the track. Smooth in action and well sorted, these forks were one of the top performers in the 1991 125 class. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1991, Suzuki made the interesting choice to move away from long-time partner Kayaba in favor of Showa hardware. At the time, Showa had come under much fire for their poor performance on Honda’s machines, but these new 45mm units broke that tradition by actually offering winning performance on the track. Smooth in action and well sorted, these forks were one of the top performers in the 1991 125 class. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the chassis side, the RM remained the sharpest-handling package in the 125 class. No matter the surface or the style of turn, the RM was ready to dive to the inside and stick like glue. On tight tracks, the RM had no equal and no other machine in the class was going to cut inside the yellow-splattered wonder. With its super-responsive motor, the RM was prone to wheelying on exit but that made it easy to loft the front end over whoops and other on-track obstacles. In the air, the RM was super maneuverable and easy to flick around but that snappy power also caused the bike to fly front-end high at times. Once you rode it for a short time it was easy to account for but riders switching between machines noted it at the time. At speed, the RM continued to be far busier than any of the 125 competition. Unlike the CR, which developed a case of the wobbles under deceleration, the RM exhibited its wandering behavior under power. At speed, the bike felt short, twitchy, and generally unsettled under the rider. Long-time Suzuki pilots got used to this busy behavior but riders switching to the RM from other machines were often disconcerted by the bike’s lack of a planted feel. Overall, it was an excellent handling package for tight and twisty courses with lots of jumps, but not the hot setup for a Glen Helen practice day in July.

Feathery: No bike in motocross was as light feeling and maneuverable in the air as Suzuki’s RM125 in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Feathery: No bike in motocross was as light feeling and maneuverable in the air as Suzuki’s RM125 in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The new Showa shock proved slightly less effective on the track than the RM’s new forks. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The new Showa shock proved slightly less effective on the track than the RM’s new forks. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the suspension front, Suzuki’s Showa gamble turned out to be a bit of a mixed bag in 1991. The new 45mm front forks performed very well and were light years better than the Showa units found on the CR125R. The spring rates and dampening were spot-on for the RM’s target demo and their performance was easy to dial in with the available compression and rebound adjustments. There was none of the mid-stroke harshness that Honda riders had been dealing with since 1989 and they were easily the best Showa forks offered since 1987.

The 1991 125 crop was certainly a colorful lot #90sMotoRuled Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The 1991 125 crop was certainly a colorful lot #90sMotoRuled Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

At the rear, the new Showa damper proved slightly less effective than the forks. In the rough, it was choppy and unwilling to follow small undulations in the terrain. This only exacerbated the RM’s busy feel at speed and made the bike a real handful in bombed-out high-speed sections. On big hits and in deep whoops it worked pretty well, but the shock never felt as plush as the 1990’s Kayaba unit. For fast guys, it worked well but riders of lesser skill missed the 1990’s smoother action.

Shredder: The RM’s strong snap made silty berms a no-drama affair in 1991. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

Shredder: The RM’s strong snap made silty berms a no-drama affair in 1991. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

On the detailing front, the RM was considered good for its time. Riders loved the bike’s comfortable ergonomics although pilots over six feet were likely to find it somewhat cramped. The new seat cover was something of an eyesore to many but the 1991 material was grippier, more durable, and provided slightly more water resistance to help keep the seat foam from prematurely deteriorating. While most people liked the feel of the RM’s switchgear, the levers were far less durable than the forged units found on the Honda. A crash that would leave you with a slightly bent clutch lever on the CR was likely to leave you with a stub of a lever on the RM. The bars, chain, and sprockets were all also utter junk, but that was par for the course for Japanese 125s in 1991. While the graphics were polarizing, at least they were durable. The shroud graphics stayed in place even for knee-brace wearers but the side plate accents were usually removed quickly to make room for numbers. The new piston and rings offered a slightly better life for 1991, but the RM continued to feel worn out faster than most of its competition. The power valve was also in constant danger of being gummed up due to its shared lubrication with the transmission oil. Once the oil came into contact with the red hot exhaust valve it turned into a thick goo that coated and fouled the mechanism. The trans oil was also prone to running low due to a vent hose incorporated into the AETC that allowed hot oil to escape. Rerouting the drain tube upwards helped somewhat, but checking the oil level and staying on top of AETC maintenance was a must if you wanted to prevent a costly failure. If you kept an eye on all of this, the RM was fun and reliable, but if you neglected it and treated it like an XR200R, it was likely to leave you stranded on the side of the track.

Bold, brash, and brazen in appearance, Suzuki’s new RM125 was a bit of an acquired taste in 1991. While its appearance was controversial, its performance was far from it. While there were faster machines available, very few were as outright fun as the feathery and flickable RM. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Bold, brash, and brazen in appearance, Suzuki’s new RM125 was a bit of an acquired taste in 1991. While its appearance was controversial, its performance was far from it. While there were faster machines available, very few were as outright fun as the feathery and flickable RM. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Overall, the mildly refreshed Suzuki RM125 turned out to be one of the most competitive machines of 1991. Despite a relative lack of peak horsepower and controversial looks, the bike was popular with riders of all skill levels. It was fun to ride, ultra-quick, and razor-sharp. The new suspension proved that Showa had not forgotten how to build a decent set of forks and the mildly massaged motor made the case for instant snap over endless wail. For high-speed work, there were better machines available, but for the majority of 125 pilots, the RM offered more than enough performance to pull you to the front.