For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at how the 125 class of 1987 stacked up in the enthusiast magazines of the time.

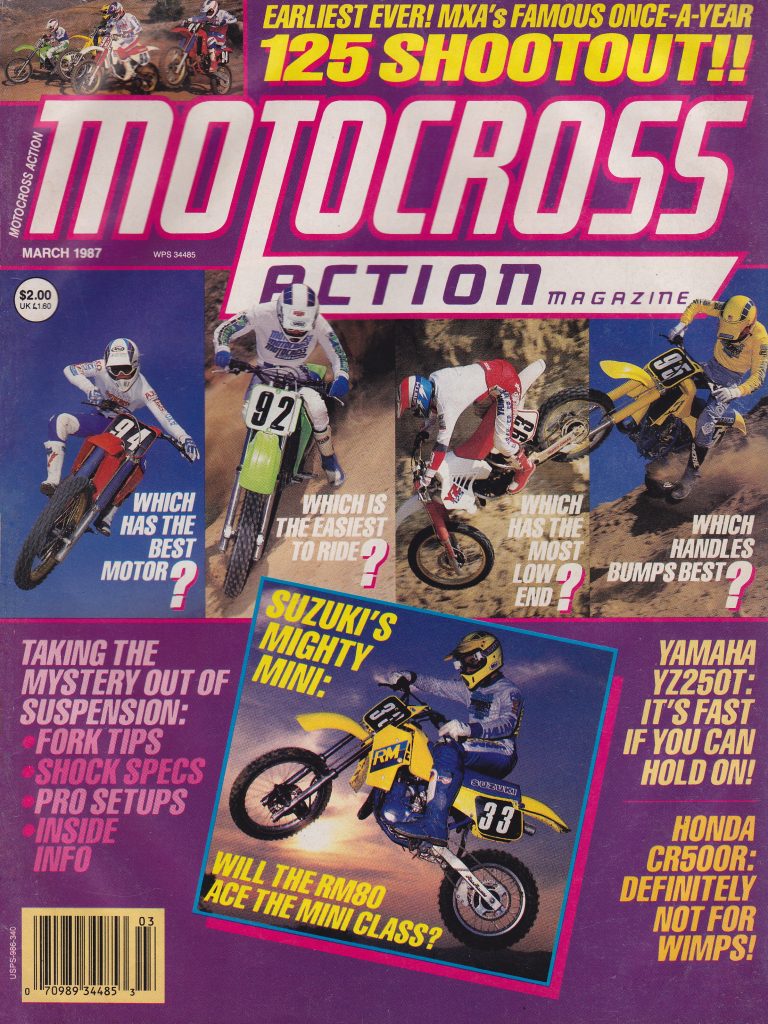

The 1980s were the glory days of MXA for me and there are not words for how excited I was to open up the mailbox and see this bit of moto goodness waiting for me when I got home from school.

The 1980s were the glory days of MXA for me and there are not words for how excited I was to open up the mailbox and see this bit of moto goodness waiting for me when I got home from school.

For this roundup we are going to compare what Motocross Action, Dirt Bike, and Cycle World thought of the 125s that season. For some unknown reason Dirt Rider did not hold a 125 shootout in 1987 so I cannot include their rankings here. They tested all four of the Japanese machines this season but failed to round them up together in one test. By 1987, Dirt Rider was firmly established as one of the most popular off-road magazines in the business, but they had an odd track record of doing shootouts some years and then skipping them others. There did not seem to be much rhyme or reason to any of this and it always struck me as very strange that they would do a 500 shootout then just ignore the much more popular 125 class. Because of this, we will have to go without their rankings here.

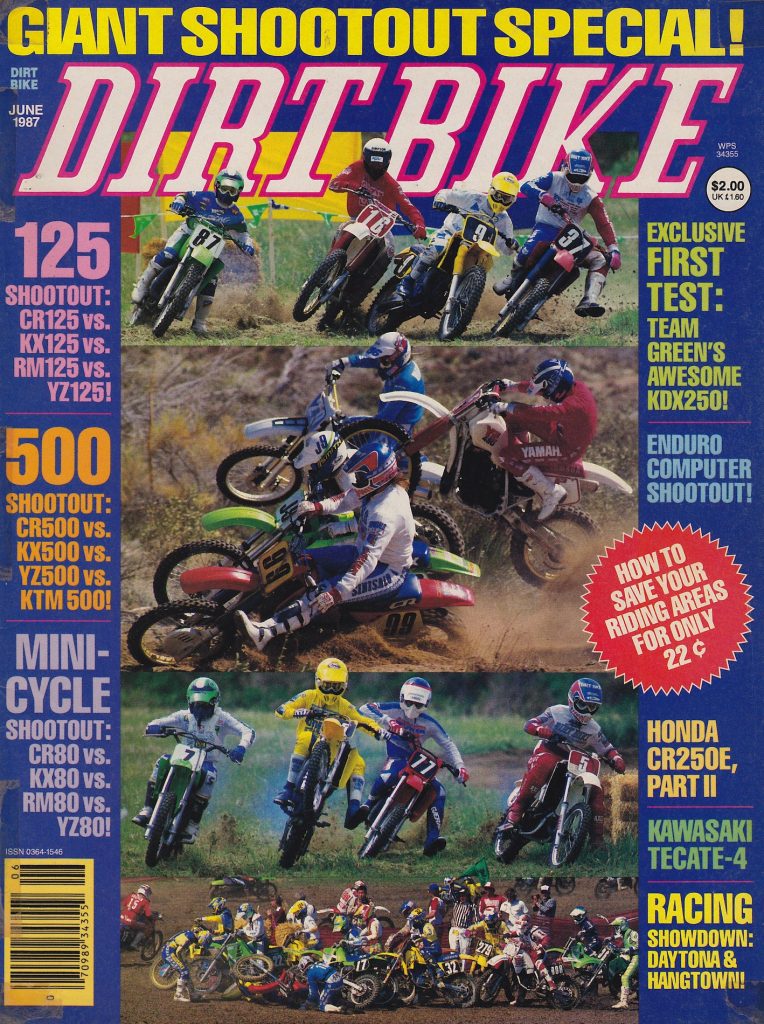

Three major shootouts in ONE issue! This was Christmas in June (probably April or May actually) to my seventeen-year-old self. Man, I miss the eighties…

Three major shootouts in ONE issue! This was Christmas in June (probably April or May actually) to my seventeen-year-old self. Man, I miss the eighties…

As in the past, I am going to list each bike’s finishing order and then give a brief rundown of its strengths and weaknesses. For this rundown we are going to focus mainly on the Big Four contenders from Japan. By 1987, most of the European 125 contenders were no longer on the average American rider’s shopping lists and major enthusiast magazines tended to ignore them. KTM did have a very trick 125 in 1987 but none of the magazines included it in their shootout. Both Dirt Bike and MXA focused solely on the Japanese offerings with Cycle World bringing Cagiva into the mix for a little Italian flavor. Here is the story of the 125 motocross class of 1987 as seen through the enthusiast magazines of the time.

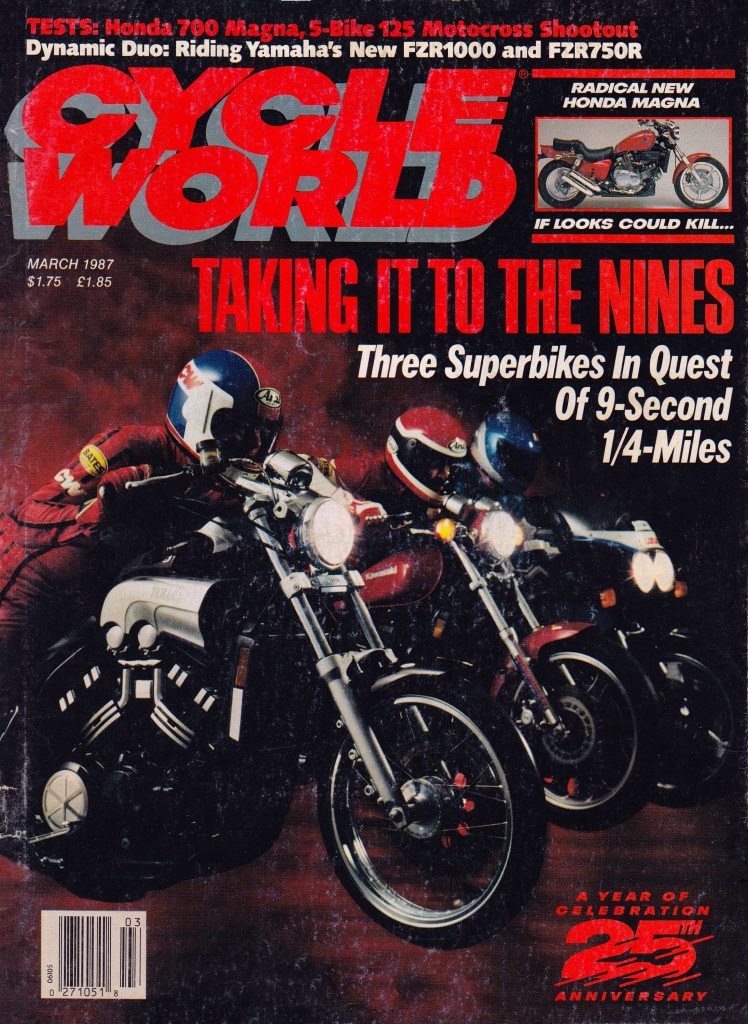

While I was never a big street bike guy, I did subscribe to Cycle World back in the eighties. I loved everything motorcycle related, and they actually had some great dirt bike reviews back then including a 125 shootout in 1987 that Dirt Rider could not be bothered to do. 😡

While I was never a big street bike guy, I did subscribe to Cycle World back in the eighties. I loved everything motorcycle related, and they actually had some great dirt bike reviews back then including a 125 shootout in 1987 that Dirt Rider could not be bothered to do. 😡

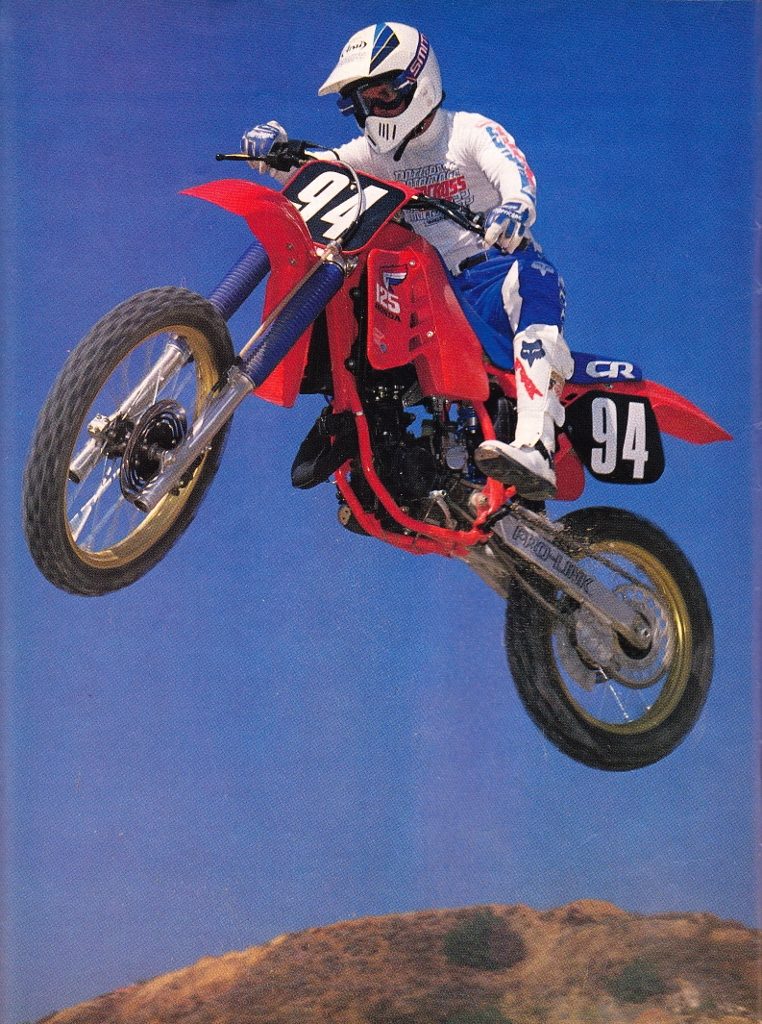

1987 Honda CR125R Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 1st (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 1st (out of 4) Cycle World – 1st (out of 5) Photo Credit: Honda

1987 Honda CR125R Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 1st (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 1st (out of 4) Cycle World – 1st (out of 5) Photo Credit: Honda

Sano looks, supple forks and the Motor of Doom; in 1987 nothing else in the 125 class was even close. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Sano looks, supple forks and the Motor of Doom; in 1987 nothing else in the 125 class was even close. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

1987 Honda CR125R Overview: In 1986, Honda owned the 125 class with a monster motor that dominated the standings. After two years of playing second fiddle to Kawasaki’s powerhouse KX125, Honda came out swinging with a revised motor that beat the Kawie at its own game. The ’86 CR barked off idle and blasted through a blistering midrange hit. It was not much of a screamer, but it pulled hard enough through the middle to keep its rivals well at bay.

For 1987, Honda made the bold choice to completely scrap its dominating ’86 platform and introduce an all-new 125 machine. The 1987 CR125R featured an all-new case-reed powerplant, redesigned frame, sleek new bodywork, and all-new suspension front and rear. An all-new disc brake was added to the rear and the renowned cartridge forks found only on the 250 and 500 in 1986 finally made their way to the CR125. While the bike enjoyed a similar look to the 1986 model, it truly was an all-new machine.

On the track, the 1987 CR125 once again dominated with the best motor in the 125 class. The new case-reed engine was softer down low than in 1986 but pulled even stronger through the middle and positively shrieked on top. Once on the pipe, it left every other machine in the class in its wake. Add in a bulletproof clutch and the best shifting in the class and you had the ultimate 125 power package of 1987.

In addition to its blistering engine performance the CR offered the best turning, flawless forks, perfect brakes, sexy looks, and excellent ergonomics. Its new “piggyback” Showa shock was fairly mediocre and its stability at speed was virtually nonexistent, but these were minor quibbles to most serious 125 pilots. Perhaps more concerning were the reliability issues tied to faulty top end bearings and air leaks at the reed valve. Both of these issues needed to be addressed and watched carefully. In spite of these peccadillos, however, the CR125R was the unanimous choice for top 125 in all three shootouts. In the 125 class, motor has always been King, and there was only one tiddler in 1987 fit to wear that crown.

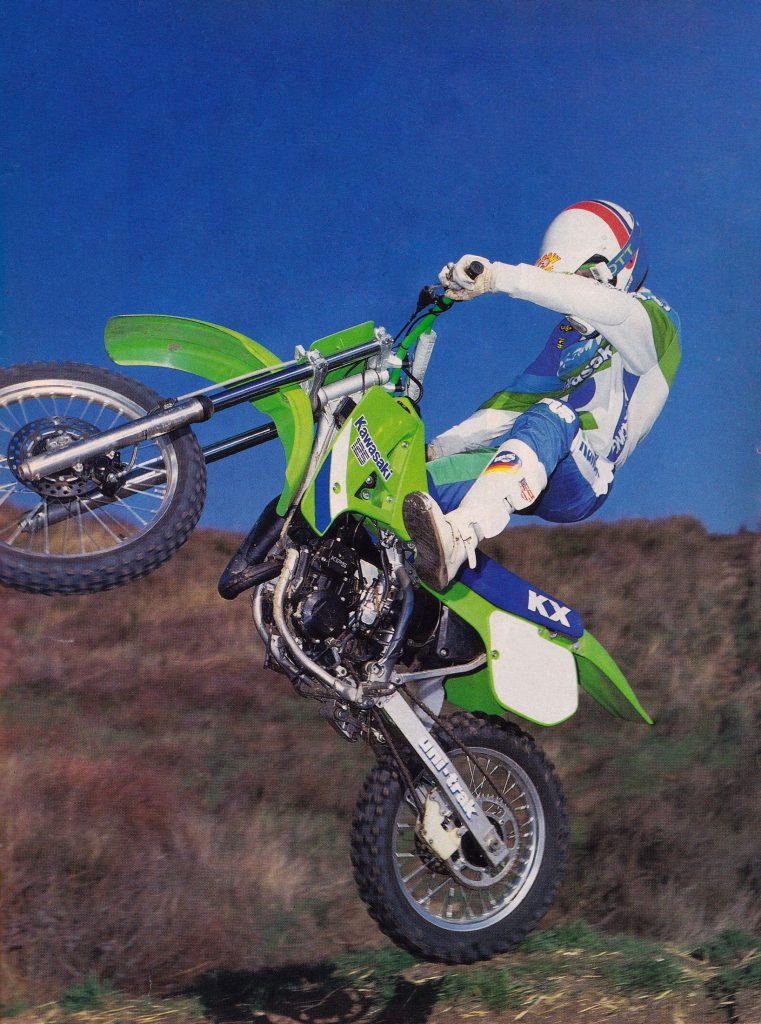

1987 Kawasaki KX125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 2nd (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 2nd (out of 4) Cycle World – 2nd (out of 5) Photo Credit: Kawasaki

1987 Kawasaki KX125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 2nd (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 2nd (out of 4) Cycle World – 2nd (out of 5) Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1987 Kawasaki addressed most of the issues that had torpedoed their 1986 effort but tried to save money in the suspension department and suffered for the decision. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1987 Kawasaki addressed most of the issues that had torpedoed their 1986 effort but tried to save money in the suspension department and suffered for the decision. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

1987 Kawasaki KX125 Overview: In 1984 and 1985 Kawasaki had waxed the 125 field with powerhouse motors that out-torqued the competition. They barked out of turns and went while the 125 competition was still trying to get spooled up. In 1986, Kawasaki abandoned its torquey roots and decided to go for revs. The result was a pro-focused motor that was faster on top and far harder to ride. Even pros found this change less than ideal and the previous champ got handed its lunch in the final standings by Honda’s far easier to ride CR125R.

For 1987, Kawasaki aimed to recapture its lost glory by shifting the powerband out of the stratosphere. An all-new cylinder shifted the exhaust to a centerport design and featured revised porting and a new concave piston for a more uniform burn. The Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System (KIPS) was also massaged and featured larger valves and lighter aluminum construction. There was a new frame to accommodate the change from a sideport to a centerport exhaust which featured an enlarged steering stem and increased bracing to prevent the frame breakages of 1986. While the new chassis maintained the same geometry as 1986, its increased strength promised improvements in on-track precision. Bodywork remained largely unchanged aside from an alteration in the side plates to accommodate the 1987’s new airbox.

On the suspension front, Kawasaki chose to save a few dollars by neglecting to install Kayaba’s new cartridge system in the forks and instead went with a modified version of the unloved Travel Control Valve (TCV) system used in 1986. A new shock was also added that deleted the high-low compression adjuster of 1986 in favor of a simpler single-knob design. The shock body was also hard-coated to increase durability and the lever ratio of the Uni-Trak was altered slightly to provide a more progressive action.

On the track, the 1987 KX125 was a significant improvement in nearly every respect. The new centerport motor pulled much better down low and carried through a solid midrange and decent top-end hook. It was far easier to ride than the peaky ’86 version and a major improvement in all respects. Pros still preferred the hard hit and endless pull of the CR but for most riders the KX offered a winning motor package.

On the handling front the KX was improved as well with the new stronger frame offering a much more solid feel than in the past. It was less lithe in the turns than the CR but also far less terrifying at speed in the rough. There was none of the Honda’s violent headshake and the KX could be bombed down rough straights that would have the CR pilot wishing he had packed a second set of undershorts. The KX’s layout was also slightly larger than the other machines and taller riders found the green machine a better fit in most situations.

Where things came undone for the Kawasaki was in the suspension department. Both ends were badly undersprung and underdamped for anyone above an absolute novice. Medium-sized jumps and large whoops crashed the KX to the stops and its old fashioned TCV forks were just not up to handling the wide variety of terrain that Honda and Suzuki’s more sophisticated forks absorbed with ease. With stiffer springs and Kawasaki’s optional cartridge upgrade kit installed the KX was capable of running with anyone in the class, but in stock condition, it was a fork away from the top spot in all of the shootouts.

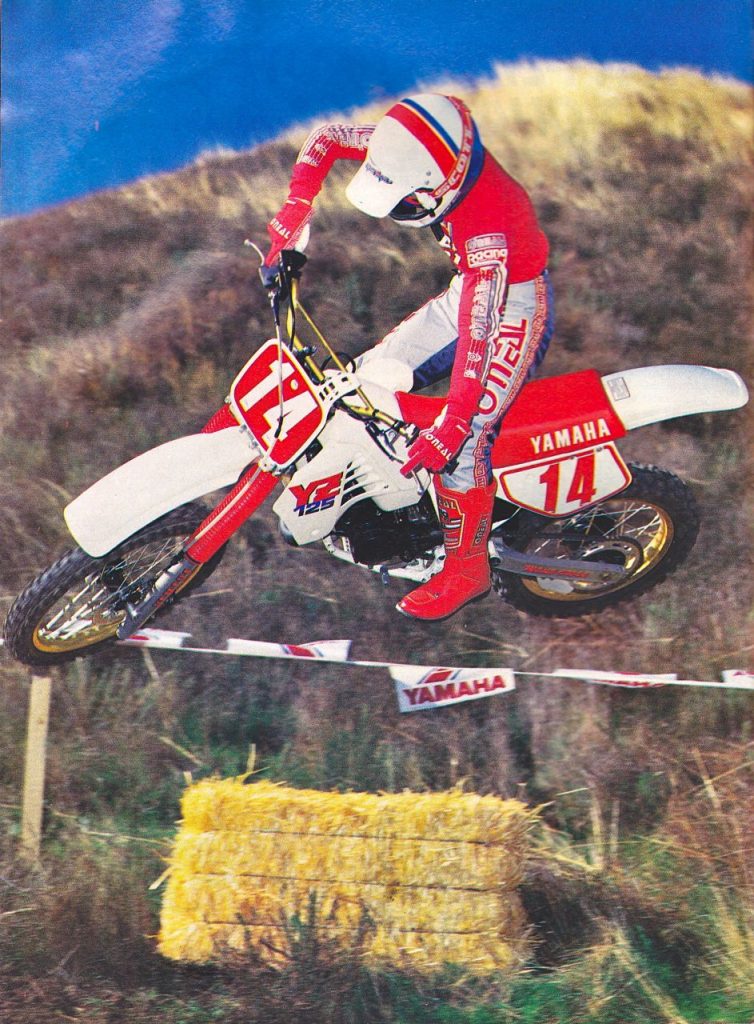

1987 Yamaha YZ125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 3rd (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 4th (out of 4) Cycle World – 5th (out of 5) Photo Credit: Yamaha

1987 Yamaha YZ125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 3rd (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 4th (out of 4) Cycle World – 5th (out of 5) Photo Credit: Yamaha

Like Kawasaki, Yamaha went the budget suspension route in ’87 and paid the price. Its punchy motor was fun but not nearly enough to make up for its truly abysmal suspension action. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Like Kawasaki, Yamaha went the budget suspension route in ’87 and paid the price. Its punchy motor was fun but not nearly enough to make up for its truly abysmal suspension action. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

1987 Yamaha YZ125 Overview: In 1986, Yamaha took a huge step forward from 125 class whipping boy to legitimate contender. The all-new ’86 YZ featured a slim new layout and a fun-to-ride powerband. It was short on breadth but long on punch and easily the most competitive Yamaha tiddler in half a decade. For 1987, Yamaha chose to focus on refinement rather than reinvention on their YZ125. The ’86 model had suffered from an annoying bog when landing off of jumps and a weak clutch that chattered and slipped when abused. To rectify this Yamaha made several changes to the engine cases and clutch mechanism to increase oil flow. They also massaged the porting and swapped out the carb in an effort to exorcise the bog and boost the top-end pull.

Like Kawasaki, Yamaha chose to keep costs down and go one more year without adding cartridge internals to their forks. This saved a few dollars but yielded predictably poor results for the tuning fork team. The YZ’s Variable Damping (VD) Kayaba forks were grim in action and easily the worst performers in the class. Unfortunately, the shock’s action was not much better, and this utter suspension ineptitude handicapped the YZ in all the magazine’s standings. In addition to its punishing ride the YZ suffered from notchy shifting, an overly light front end, and a complete lack of top-end power.

With its snappy low-to-mid power and a light feel, Motocross Action thought the YZ held a lot of potential and ranked it third behind the KX and CR. For the others, however, its narrow power spread, recalcitrant shifting, and stone-age suspension action relegated the Yamaha to last. In the case of Cycle World, that meant it even lost out to Cagiva’s Italian Stallion the WMX125. With some suspension work the YZ could certainly run at the front but in stock condition it was too unrefined to threaten the best machines in the class.

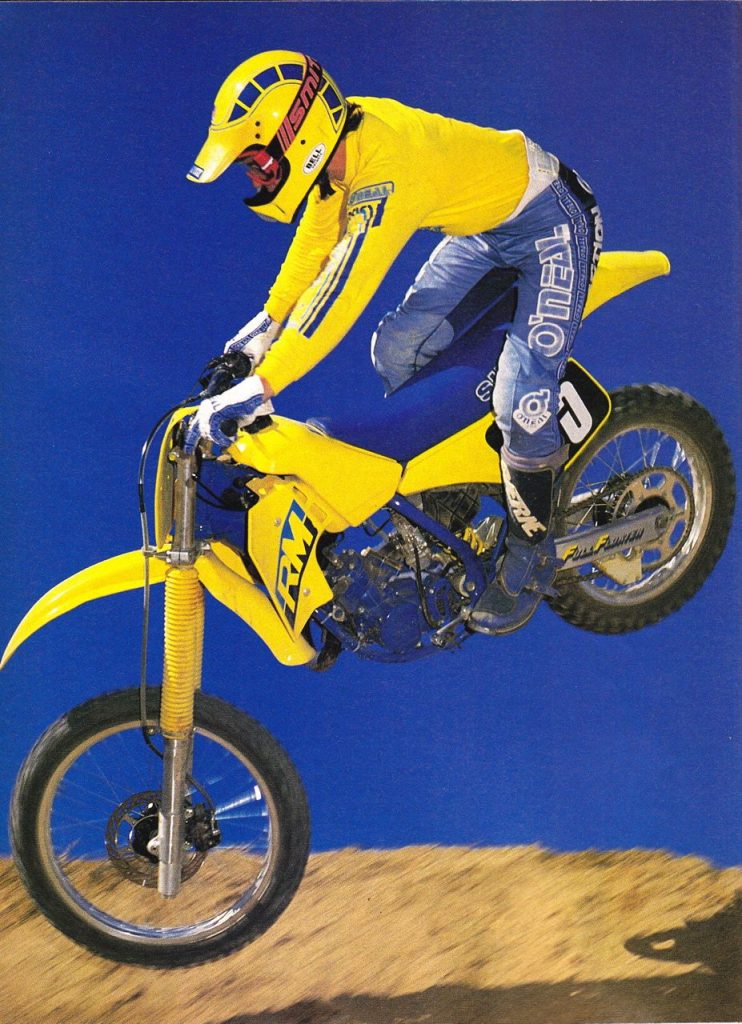

1987 Suzuki RM125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 4th (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 3rd (out of 4) Cycle World – 4th (out of 5) Photo Credit: Yamaha

1987 Suzuki RM125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 4th (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 3rd (out of 4) Cycle World – 4th (out of 5) Photo Credit: Yamaha

The RM125 made huge strides forward in suspension performance in 1987 but continued to lack the power to be a legitimate contender.

The RM125 made huge strides forward in suspension performance in 1987 but continued to lack the power to be a legitimate contender.

1987 Suzuki RM125 Overview: In 1986, Suzuki swung for the fences on their RM125 and struck out miserably. The all-new, but old-look RM suffered from gutless power, poor ergonomics, a sticky shock and cranky handling. It offered a “seventies style” of 125 power that was all-rev and no grunt. This made the bike far too difficult to ride for most riders below the pro class and relegated the RM to last in the majority of the ’86 shootouts.

For 1987, Suzuki once again threw the kitchen sink at the RM125 in an attempt to pull the yellow machine out of the basement of the 125 standings. There was an all-new motor with a completely redesigned power valve, all-new suspension that ditched the stiction-prone eccentric cam linkage of ’86 in favor of a more traditional link-arm design, all-new forks that incorporated Kayaba’s version of Honda’s cartridge fork system, and a new frame narrowed the midsection for an improved feel. About the only thing that Suzuki did not change was the bodywork, which continued to look like a holdover from 1984.

On the track, the RM was a major improvement in one category and a push in all the others. The new cartridge forks and redesigned Full Floater were fantastic and gave the RM the best overall suspension package in the class. It was supple, well controlled, and capable of handling novices and pros with equal ease. Aside from that, however, the RM was little more than a recycle of 1986. The chassis felt hinged in the middle and inaccurate at all times. The new motor was stronger on top but still pathetic anywhere else. If you could keep it at full boil it was fast, but if you hesitated for a split second it fell off the pipe and demanded two downshifts and a flogging of the clutch to get back going. The cramped ergonomics were panned by all and the bike continued to look as if the bodywork was designed by two different committees that never bothered to talk to each other.

For Dirt Bike and Cycle World, the RM’s suspension prowess was enough to bump it above the wrist-busting YZ in the standings. Neither machine was a perfect handler, and both featured narrow power spreads (albeit at different extremes on the curve), but the RM’s superior suspension made going fast easier in their estimation. For Motocross Action the RM’s suspension advantage was just not enough to make up for its utter lack of low-end power. The bike was fine for pros but frustrating for anyone else and just too hard to ride to finish above the flawed but fun YZ.

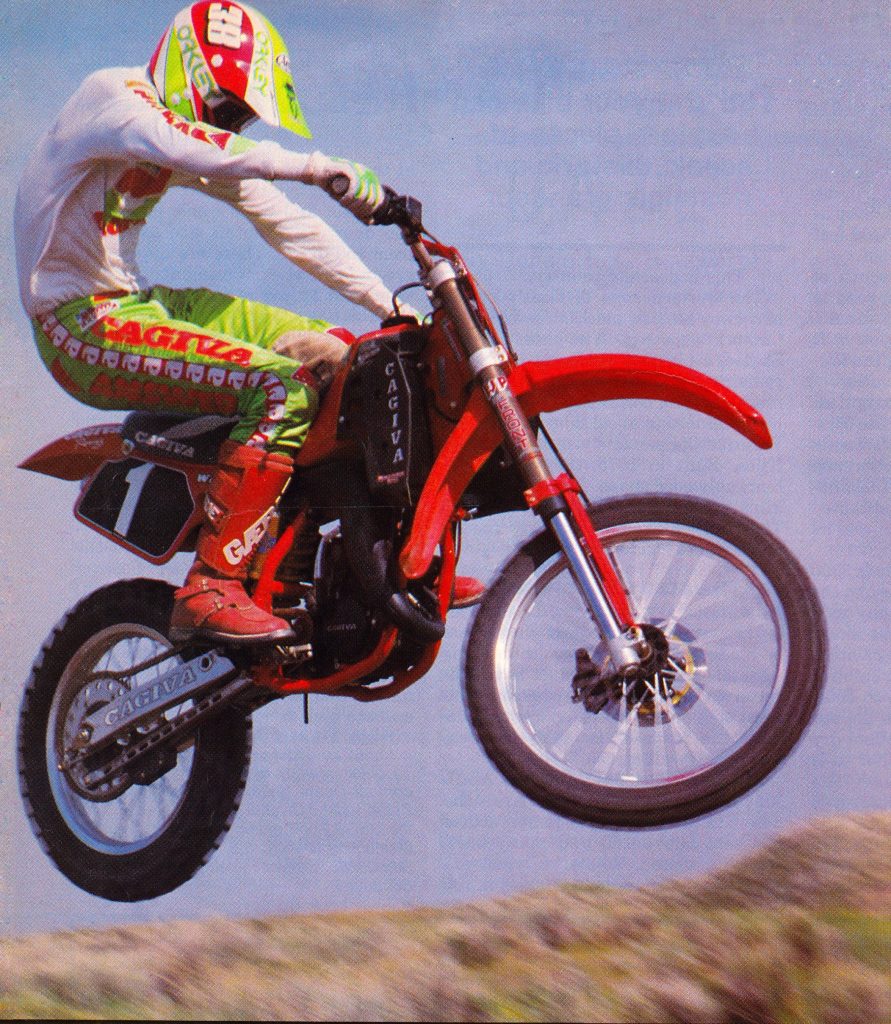

1987 Cagiva WMX125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – N/A Dirt Bike – N/A Cycle World – 3rd (out of 5) Photo Credit: Cagiva

1987 Cagiva WMX125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – N/A Dirt Bike – N/A Cycle World – 3rd (out of 5) Photo Credit: Cagiva

While more of a curiosity than a contender to most American riders of the time, Cagiva’s WMX125 had a lot to offer in 1987. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

While more of a curiosity than a contender to most American riders of the time, Cagiva’s WMX125 had a lot to offer in 1987. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

1987 Cagiva WMX125 Overview: Today the Cagiva name is mostly forgotten in motocross circles but the brand has a long heritage that dates all the way back to Harley-Davidson’s failed motocross experiments of the 1970s. After the MX-250 failed to catch on, AMF/Harley-Davidson decided to cut their losses and sell their Italian motorcycle holdings to Claudio and Gianfranco Castiglioni in 1978. The brothers founded Cagiva soon after and set about turning Harley’s failure into an Italian motocross success. By 1985, Cagiva had a 125 World Motocross title to their credit with Finnish rider Pekka Vehkonen at the controls.

While Cagiva enjoyed plenty of success on the world stage they continued to struggle for acceptance in America. Very few machines made it into the US market and most magazines of the time largely ignored them. In spite of this, however, the Cagiva 125s of the mid-eighties were highly competitive machines. The motors were as fast as anything in the class and their high dollar Öhlins and White Power suspension components were some of the best available at the time. When tested, it was mostly the suspension setup and the unique “Euro” feel they exuded that held them back in the final standings. Rock-hard seats, “sit on” ergonomics, and suspension set up for Europe’s high-speed tracks all seemed weird to a generation of riders raised on Japanese machines.

For 1987, Cagiva once again took a stab at breaking into the American motocross market with an updated version of their 1986 “World Championship Replica” machine. Cagiva looked to boost power by adding new porting, reshaping the power valve, redesigning the exhaust, and ditching the ’86 model’s Dell’Orto in favor of an all-new “oval-slide” Keihin PJ carburetor. The 1986 model’s conventional Marzocchi 43mm forks were also replaced with White Power’s latest 4054 inverted forks. In 1987, these were some of the most advanced suspension components available and set the Cagiva apart from its ubiquitous rivals. In the rear, the ’87 WMX continued to use a premium Öhlins shock to handle the damping duties, but a heavier spring was added and new valving was installed to help smooth out the Italian’s suspension action.

On the track, the Cagiva continued to be a competitive but rather unique experience. Like the Yamaha, the motor was very fast when on the pipe but not very long on duration. It hit hard in the midrange but preferred to be shifted rather than wrung out like the CR or RM. Low-end power was sufficient to pull the WMX out of tight turns, but it lacked the “right now” snap of the YZ. Overall, it was a good 125 motor that required a deft hand and quick left foot to keep it in the meat of its usable power spread.

As with previous Italian machines, the majority of the complaints originated with the feel of the bike and its suspension action. Compared to the Japanese bikes in the test the Cagiva felt tall and its firm saddle gave the impression of sitting on top of the bike instead of “in” it. Today, this would seem perfectly normal but in 1987, the Cagiva felt rather out of place. The overall feel of the controls and layout were also different than the Japanese machines. This was something riders could adapt to, but it put the WMX at a disadvantage when compared back-to-back with more familiar machines from Japan.

On the suspension front the new 4054 inverted forks received rather mixed reviews. Some riders liked their action while others found them harsh. Nearly everyone found them too soft and jump-filled tracks quickly exceeded their stock settings. Both the forks and shock were lightly sprung, and the WMX could be easily bottomed on Supercross-style hits. These settings probably worked very well on the rolling natural terrain courses of Europe but they were a bit out of step with the jumpy US tracks of the time. As ATK had shown, both the White Power forks and Öhlins shock could be made to work flawlessly with proper setup but in stock condition they were in need of a bit of fine tuning.

Overall, the 1987 Cagiva was a thoroughly modern and highly competitive machine in need of a little fine tuning and a better dealer network. If more riders had been given the opportunity to race a Cagiva it is pretty certain they would have made a bigger dent in the States. With the acquisition of Husqvarna in 1987, the Cagiva brand would soon be transitioned to the more well-known Swedish name and go on to win several more World Motocross titles in the 1990s. While they would never become a mainstream hit in the USA, the Cagiva brand made good on the promise of the seventies Harley-Davidson motocross experiment and showed that the Italians were more than capable of building a machine that could take on the world’s best.