For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at one of the most beloved Enduro machines of the late seventies and early eighties, Suzuki’s PE175.

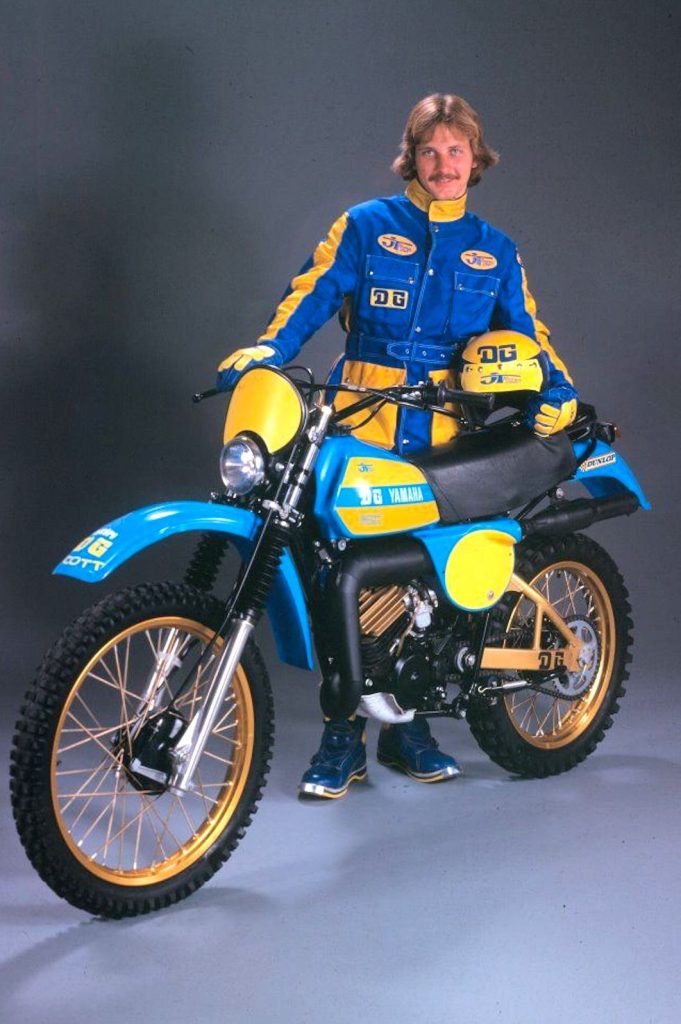

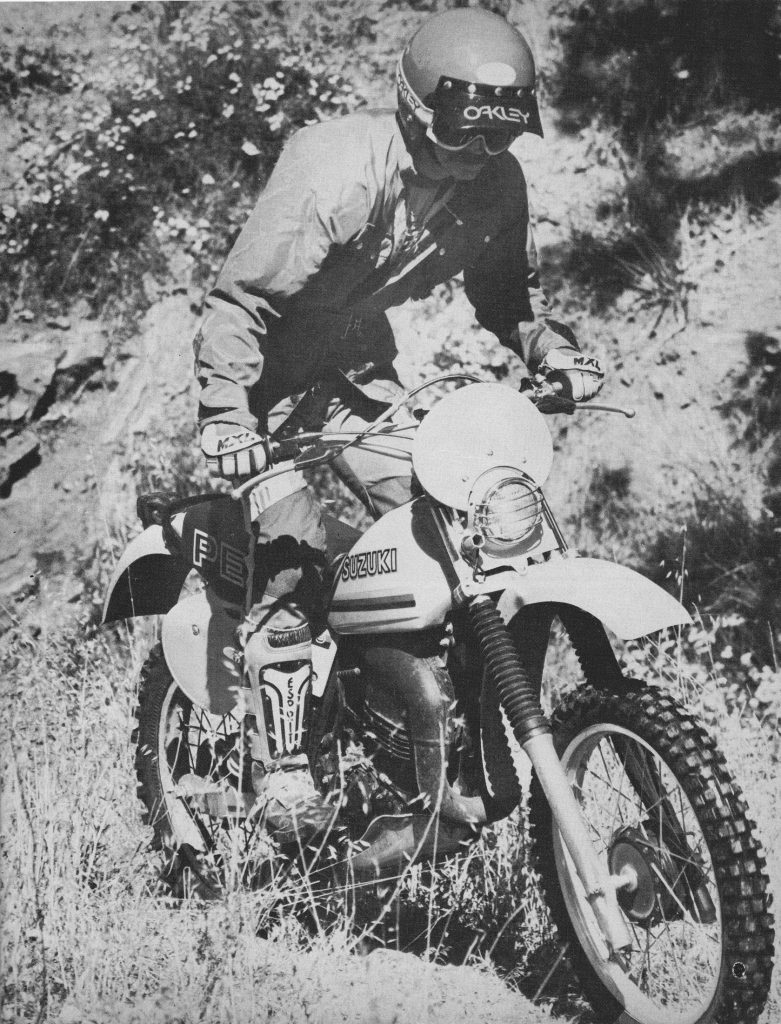

In 1978, Suzuki debuted its answer to Yamaha’s successful IT175. Based off of their award-winning RM125, the all-new PE offered excellent performance in a light and easy-to-ride package. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1978, Suzuki debuted its answer to Yamaha’s successful IT175. Based off of their award-winning RM125, the all-new PE offered excellent performance in a light and easy-to-ride package. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Originally launched in 1978, the PE175 was Suzuki’s answer to Yamaha’s popular IT175. At the time, the 175 Enduro class was just starting to heat up with the established contenders from Can-Am and Penton (KTM) just starting to be legitimately challenged by the Japanese. In 1975, Honda had introduced their entry into the 175 class with the MR175. Based loosely on their incredibly popular CR125M Elsinore, the MR was a capable trail bike, but not much of a performance player. It was badly underpowered compared to the competition and not much of a threat to machines like the Penton Jackpiner. Two years later in 1977, Yamaha threw their hat into the 175 Enduro ring by introducing a small-bore version of their 400cc “International Trials” machine. Once again based on a 125 motocrosser, the new IT175 proved incredibly popular with its advanced “monoshock” rear suspension and rock bottom $998 price tag. This sum was half what some of the IT’s European competitors were charging at the time and a screaming deal for anyone looking for a lightweight woods machine.

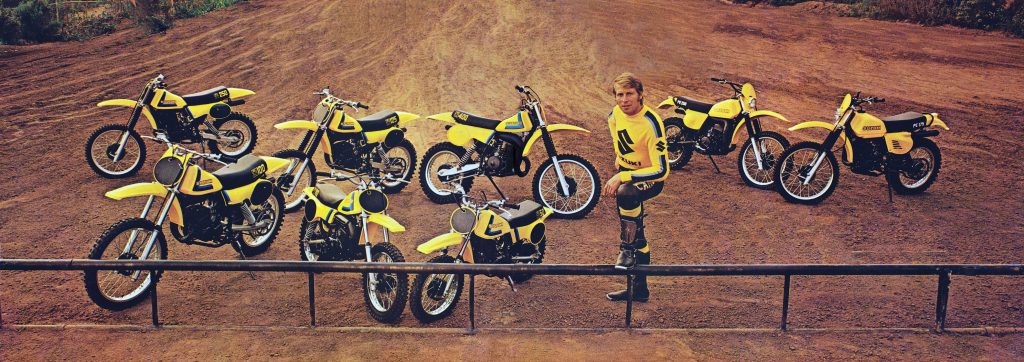

Originally launched in 1977, Suzuki’s “Pure Enduro” line capitalized off the success of their excellent motocross machines by bringing much of that winning technology to the off-road market. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Originally launched in 1977, Suzuki’s “Pure Enduro” line capitalized off the success of their excellent motocross machines by bringing much of that winning technology to the off-road market. Photo Credit: Suzuki

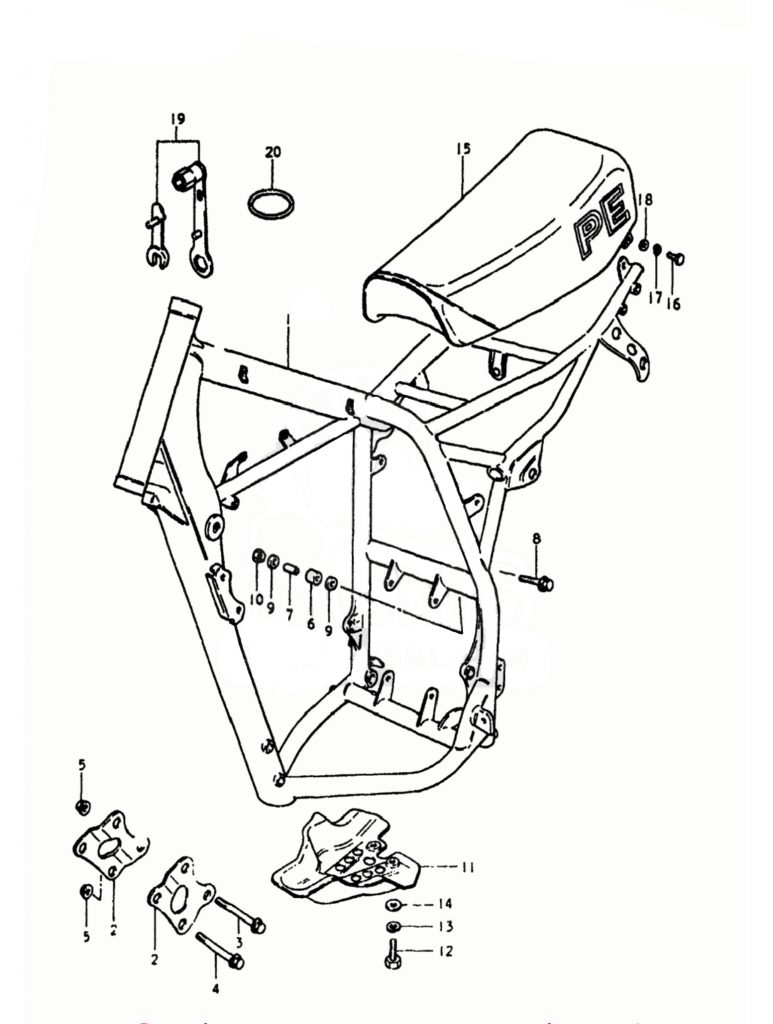

In 1978, Suzuki entered the 175 fray by following the Honda and Yamaha model and raiding their 125 parts bin. The all-new “Pure Enduro” 175 featured a frame and motor based on the hugely popular ’76 RM125A. Both the RM and PE shared the same 30-degree steering head angle and 130mm of trail. This geometry was less aggressive than the latest RM125 featured in 1978 but it was deemed more suitable for the PE’s intended purpose. The overall dimensions of the frames were nearly identical but the PE did feature a smaller-diameter swingarm in the rear and the use of mild steel instead of the RM’s chromoly for its construction. In the switch to off-road use, extra tabs were also added to the frame for the needed Enduro hardware, and a loop was welded on to the rear to secure the PE’s larger rear fender.

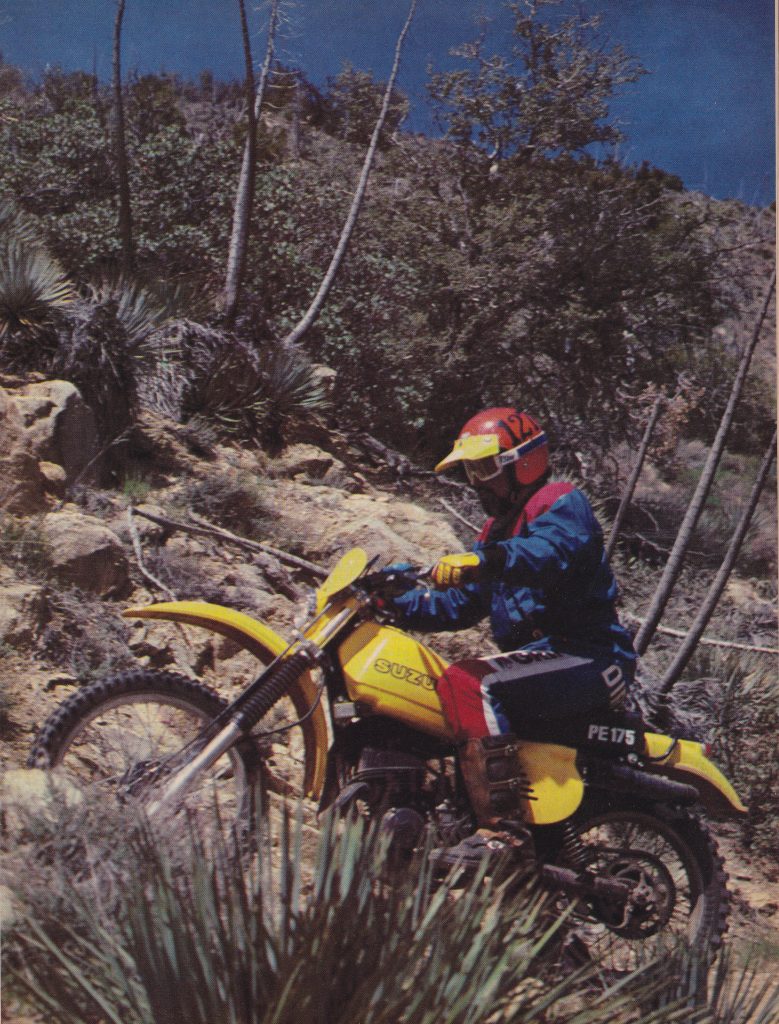

Small Enduro bikes such as the IT175, PE175, KDX175, and XR185 were hugely popular in the late seventies and early eighties due to their light weight, affordable price, and easily accessible performance. Photo Credit: Cycle World

Small Enduro bikes such as the IT175, PE175, KDX175, and XR185 were hugely popular in the late seventies and early eighties due to their light weight, affordable price, and easily accessible performance. Photo Credit: Cycle World

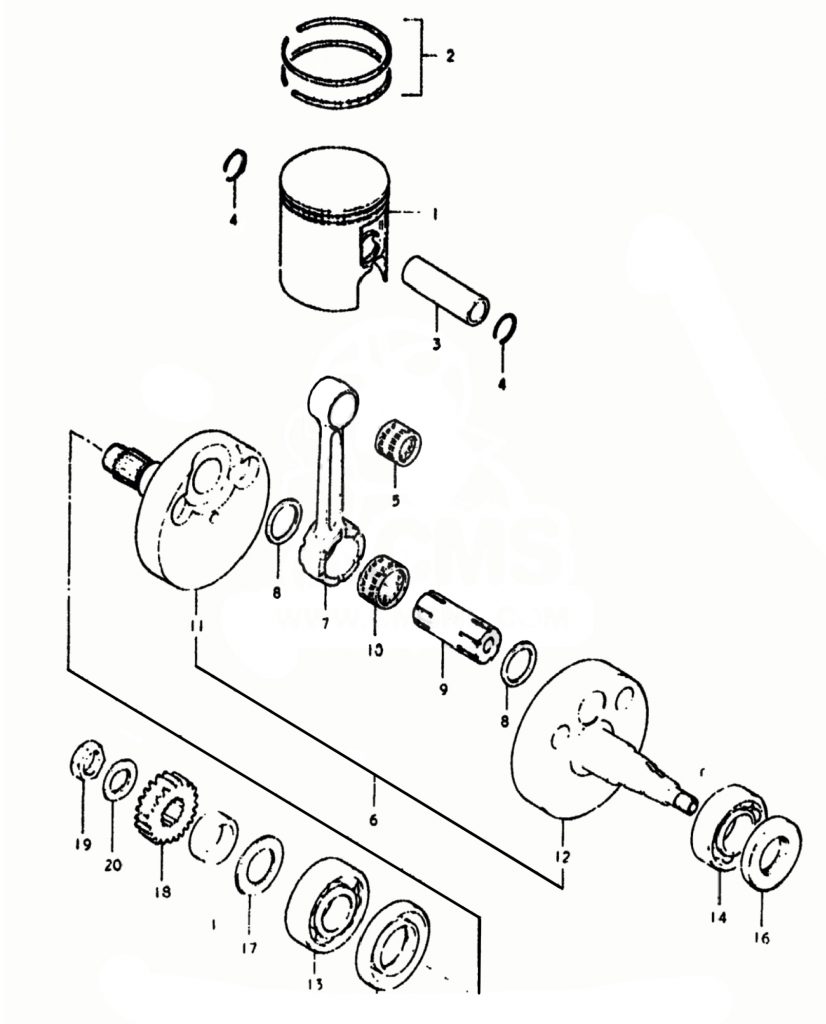

On the engine side, the PE175 featured a bored and stroked version of the air-cooled “Power Reed” motor employed on the RM125. In use since 1976, the Power Reed consisted of a hybrid piston-port and reed-valve induction setup that looked to combine the advantages of both to provide the widest possible spread of power. In addition to offering more displacement, the new PE mill featured beefed-up components throughout. Both the connecting rod and crankpin were enlarged, with the small and big end bearings also receiving an upgrade in size. The wrist pin was increased 2mm in diameter and the piston skirt was lengthened to increase reliability and prevent rocking within the cylinder. With the increase in bore and stroke, the PE’s overall displacement bumped up to a full 172cc. The porting was also exclusive to the PE with the new profile favoring low-end torque over the motocrosser’s shrieking revs. Both machines shared the same 32mm Mikuni VM32SS carburetor and Suzuki’s Pointless Electronic Ignition (PEI), but the PE featured a new external-rotor flywheel to provide additional mass and enough juice to power a set of lights.

Established European Enduro mounts like this KTM (or Penton depending on where you bought it) offered higher performance than the Japanese but at a substantially greater price. Photo Credit: KTM

Established European Enduro mounts like this KTM (or Penton depending on where you bought it) offered higher performance than the Japanese but at a substantially greater price. Photo Credit: KTM

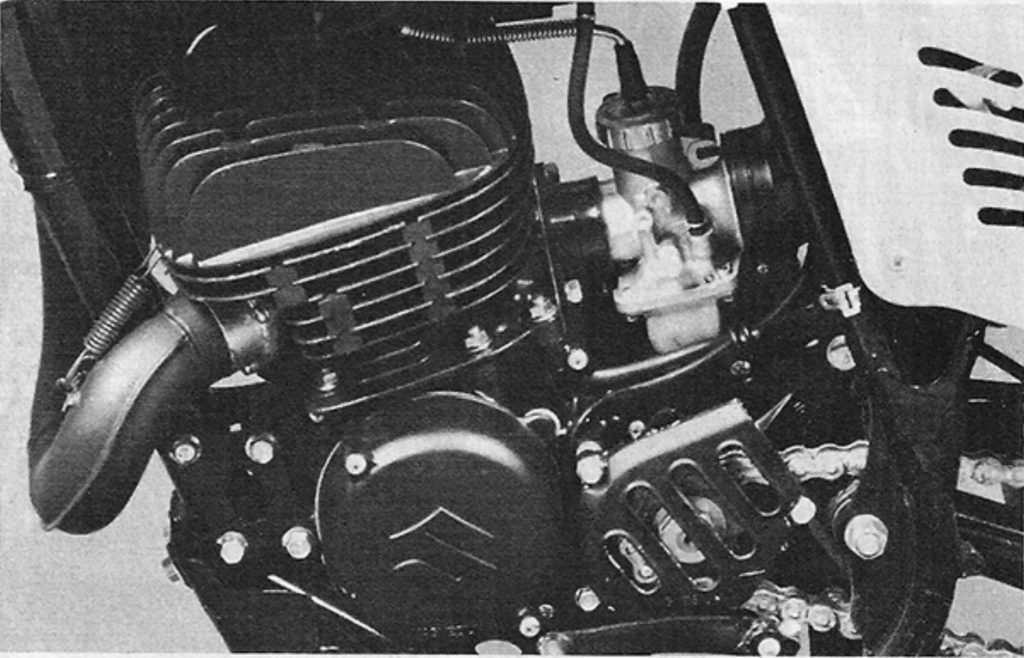

To be certified as EPA legal, the PE had to meet strict sound standards so both the airbox and exhaust were far more restricted than the units found on the RM. This helped make the PE more waterproof but did nothing to assist the bike’s power. The PE’s exhaust system featured a baffle midway down the expansion chamber and a very restrictive spark-arrested silencer. This made the bike very quiet and kept Smokey the Bear happy, but also severely neutered the stock machine’s performance.

A larger bore, longer stroke, and beefed-up bottom end boosted the torque and increased the durability of the PE’s RM-based motor. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A larger bore, longer stroke, and beefed-up bottom end boosted the torque and increased the durability of the PE’s RM-based motor. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the bottom end, the PE175 once again used a set of modified RM cases. Many internal parts inside the transmission were interchangeable but the PE did feature wider ratios to better suit its off-road aspirations. Many of the clutch components were also interchangeable but the PE’s clutch did feature two additional plates for improved durability. With its wide-ratio gearbox, top speed was set at an RM-dusting 69 mph.

Suzuki’s Enduro lineup consisted of a lightweight 175 and a middleweight 250 in 1978. Photo Credit Suzuki

Suzuki’s Enduro lineup consisted of a lightweight 175 and a middleweight 250 in 1978. Photo Credit Suzuki

The bodywork on the new PE was similar in looks to the RM, but the Enduro version featured larger fenders, a 3.2-gallon plastic tank (double the capacity of the RM), and lights front and rear. Remarkably, overall suspension travel remained very close to the travel offered on the motocross model with 9.1-inches up front and 9.0-inches in the rear. This was in contrast to competition like the IT175, which lopped a full two inches off the travel enjoyed on the YZ125. While the suspension travel was similar, the two machines did not share the same components. Up front, the PE lacked the RM’s air-adjustable fork caps and in the rear, the shocks did not enjoy the same remote reservoirs as the motocross model. Internally, both the springs and damping settings were also much softer than those employed on the RM.

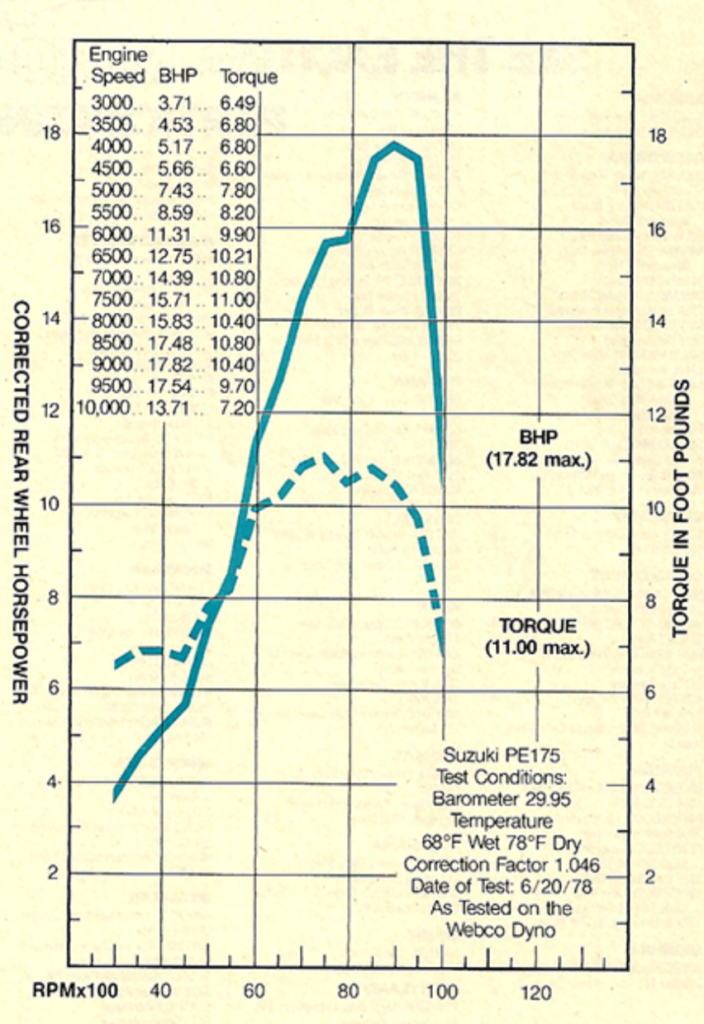

With only 17.82 horsepower and 11 foot-pounds of torque on tap, the stock ’78 PE175 was not going to win any stump-pulling contests, but its motor was pleasant, torquey, and easy to manage. Photo Credit: Cycle

With only 17.82 horsepower and 11 foot-pounds of torque on tap, the stock ’78 PE175 was not going to win any stump-pulling contests, but its motor was pleasant, torquey, and easy to manage. Photo Credit: Cycle

On the trail, the new PE turned out to be an excellent performer in every category but one. Its RM-based chassis and long-travel suspension provided one of the best handling packages in the class. Its turning manners were very good in the woods and everyone praised its light feel and excellent ergonomics. That feel was not just an illusion either as the PE tipped the scales at a very light 216-pounds. That made it the lightest bike in the class (by more than twenty pounds in some cases) and helped every facet of the PE’s handling. Both the forks and shock were ultra-plush and well-suited for plonking down the trail or snaking through the trees at speed. The longer-travel suspension also gave it more than a two-inch ground clearance advantage over the IT, with the Suzuki gliding over obstacles that the Yamaha bashed into. If high-speed desert work was in the cards then the PE’s suspension was going to be too soft but for most traditional Enduro applications the little Suzuki was an excellent choice.

If you removed the PE’s corked-up stock exhaust system and replaced it with an aftermarket alternative the power of the little Suzuki improved immensely. Photo Credit: Cycle

If you removed the PE’s corked-up stock exhaust system and replaced it with an aftermarket alternative the power of the little Suzuki improved immensely. Photo Credit: Cycle

Where the PE’s domination went somewhat astray was in the engine category. Mostly because of its absurdly choked-off exhaust, the PE was badly underpowered compared to its rivals. In 1978, nothing was close to the power being pumped out by the Can-Am’s rocket-fast rotary-valve Rotax, but even compared to the IT175 the PE was a 216-pound weakling. On the dyno, it gave up a whopping 3.3 horsepower to the IT and almost 5 horsepower to its little brother the RM125. On the bright side, the PE was far torquier than the IT and very pleasant on the trail. Tight trees, rocks, and roots were its wheelhouse and there the PE excelled. Once the trail opened up, however, the stock PE was likely to be left in the dust. When Cycle magazine tested the PE and IT in 1978, the Yamaha pulled a five-to-six bike length lead every time in a run to top speed. On steep hills and fast wide-open sections, this power deficiency was very noticeable, but in the woods, it was less of a hindrance. Thankfully, this power inadequacy was easily addressed by ditching the stock pipe and silencer for something without a massive baffle in it. This did make the bike a bit louder but also really woke up its powerband.

High-flying antics were not its forte, but the PE’s light weight, long-travel suspension, and RM-based chassis made it an able flyer when necessary. Photo Credit: Cycle

High-flying antics were not its forte, but the PE’s light weight, long-travel suspension, and RM-based chassis made it an able flyer when necessary. Photo Credit: Cycle

Overall, the 1978 PE175 was an excellent first effort for Suzuki and by far the most competitive Enduro machine offered up to that point by the Japanese. There were certainly faster machines available, and ones with more storied pedigrees, but if you were looking for the best do-it-all small-bore Enduro of 1978 you could not go wrong with the Suzuki PE175.

For 1979, the PE175 received several small changes aimed at improving servicing and increasing performance. Photo Credit Suzuki

For 1979, the PE175 received several small changes aimed at improving servicing and increasing performance. Photo Credit Suzuki

For 1979, the small-bore Enduro market got even more interesting with the return of Honda to the class. After two years off, Big Red was back with a new four-stroke designed to do battle in the woods. The all-new XR185 featured a rugged two-valve motor, dual shocks, and full Enduro hardware. Not at all related to its two-stroke motocross brethren this time, the new XR was easily the most unique machine available in the ’79 small-bore Enduro division.

Honda’s all-new XR185 added a little variety to the lightweight Enduro class in 1979. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda’s all-new XR185 added a little variety to the lightweight Enduro class in 1979. Photo Credit: Honda

While the new XR185 was not much of a powerhouse, its meager output was actually not much behind a stock PE175. Knowing this power deficiency was the main complaint of riders the year before, Suzuki set about uncorking their 175 somewhat for 1979. First to go was the overly baffled pipe which had been the main culprit in the ’78 model’s meager top-end performance. In its place, Suzuki installed a new “fuzzy walled” expansion chamber that replaced the solid baffle of 1978 with a new layer of mesh encircling the interior of the pipe. The hope was that this new mesh design would provide the same level of sound deadening as the ’78 design without the penalties in power output. In addition to the new pipe, Suzuki also installed a new larger carburetor for 1979. The new mixer grew from 32mm to 34mm and aimed to cajole a bit more top end out of the PE’s 172cc. Lastly, the engineers upped the weight of the crank slightly to boost the PE’s chug factor for 1979.

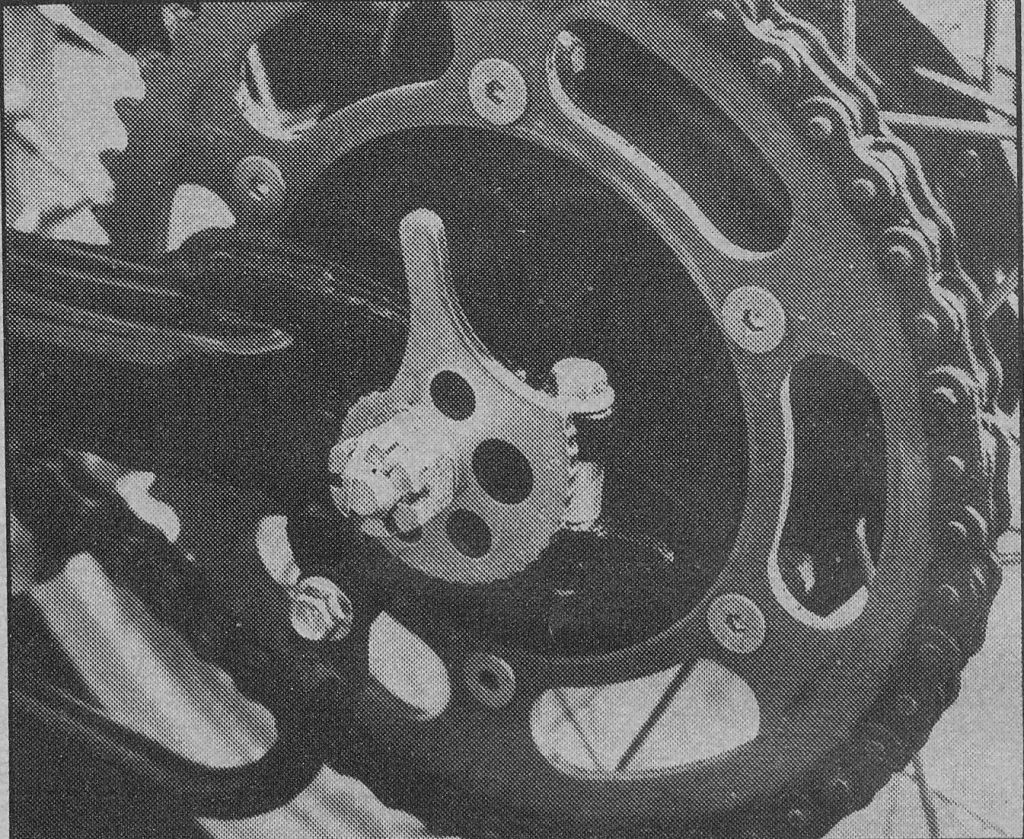

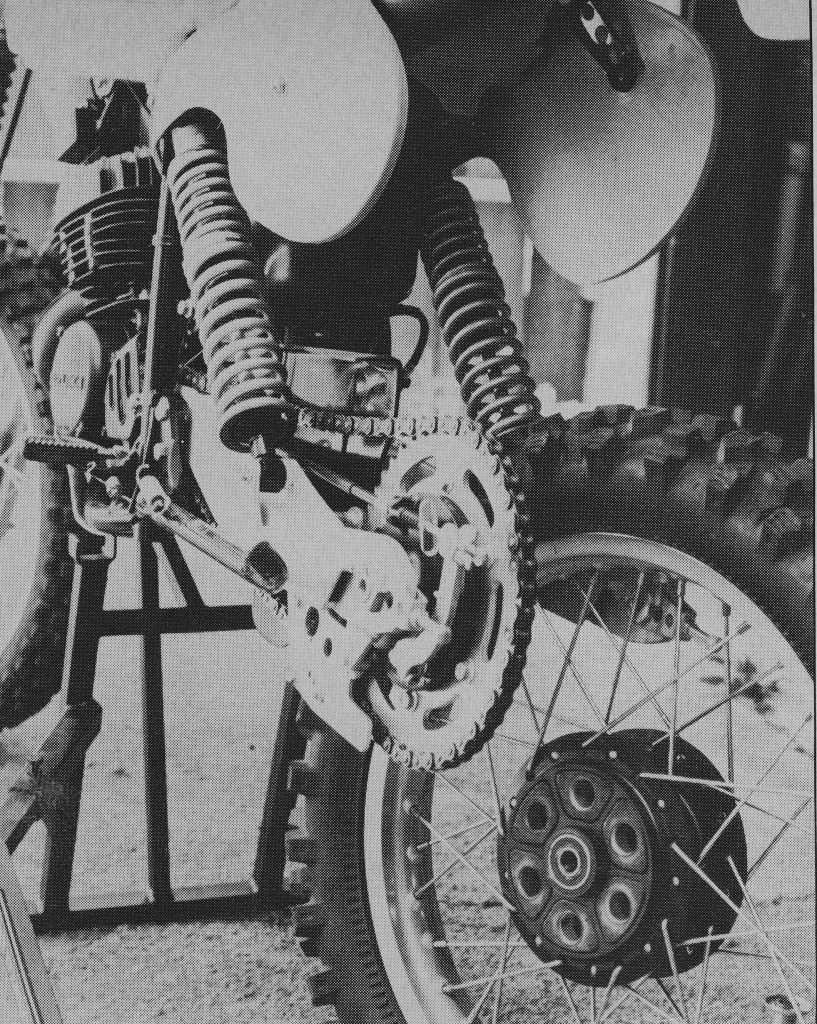

A new “snail-type” chain adjuster aided trail-side servicing in 1979. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

A new “snail-type” chain adjuster aided trail-side servicing in 1979. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the chassis front, the PE remained largely unchanged but there were a few upgrades aimed at making the PE more race-ready. Chief among these was a redesigned rear axle that incorporated a quick-change feature for the first time. The ’78 model’s motocross-style adjusters were replaced with all-new snail-type units that made trailside adjustments much easier.

Yellow Magic: Suzuki was a performance powerhouse in 1979. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Yellow Magic: Suzuki was a performance powerhouse in 1979. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In terms of actual performance, the changes made for 1979 were a bit of a mixed bag. The new pipe did perform slightly better on top but the PE continued to be pretty flat through the middle and actually worse down low. The new larger carburetor proved difficult to jet cleanly and many testers believed the bike ran better with the smaller mixer. The heavier crank and poor jetting muted the bike’s low-end response and most riders preferred the snappier ’78 power plant. Once again, ditching the stock exhaust and fiddling with the jetting helped immensely but the PE remained a great bike in need of a few more ponies. Other than the motor, the PE’s performance remained unchanged. Fast guys thought the suspension was too soft but most log-hoppers liked its performance. The bike’s handling split the difference between turning and stability nicely and the bike’s controls and overall feel were praised for their comfort. On the demerits side were the PE’s continued use of a non-folding brake and shift levers (curious and nearly unforgivable on a bike made for Enduro use), slightly stubborn shifting (bring a big boot), water-flummoxed brakes (once wet, it was best to just drag your feet), and power-robbing exhaust. Overall, the 1979 PE175 was still very competitive but with additional competition on the horizon, Suzuki’s smallest Enduro would need to up its game if it had any intention of staying at the front.

Even though the PE175 was more at home in the woods than out West, its predictable handling and plush suspension made it a fun desert explorer. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Even though the PE175 was more at home in the woods than out West, its predictable handling and plush suspension made it a fun desert explorer. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

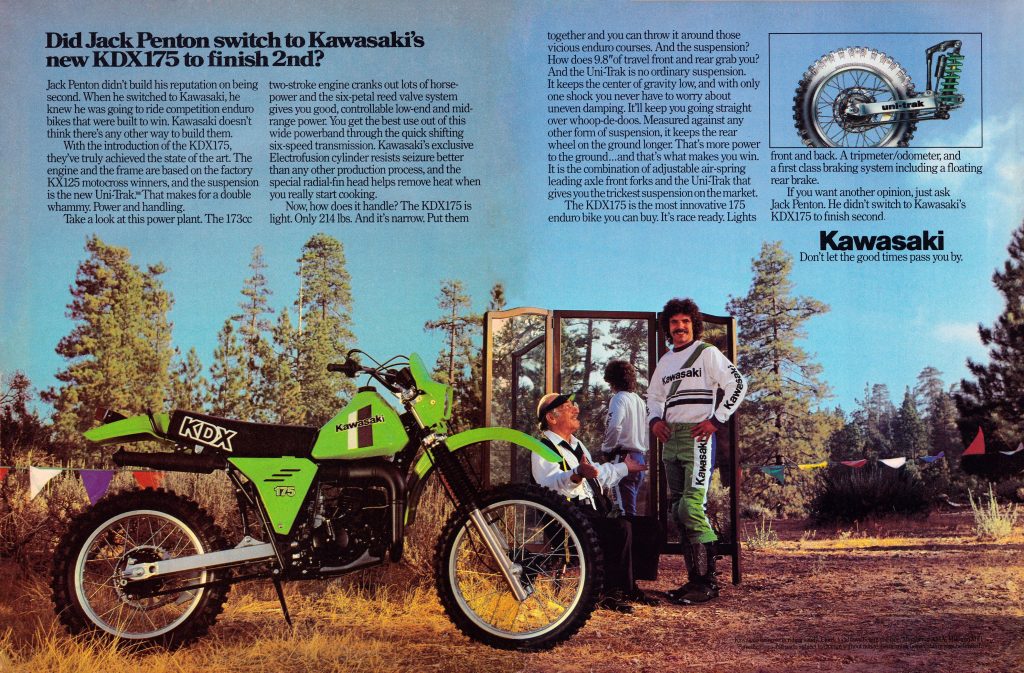

For 1980, the 175 division got even more crowded with the introduction of Kawasaki’s new entry, the ground-breaking KDX175. Based on the all-new monoshock KX125, the KDX featured a cutting-edge chassis, powerful motor, and the most sophisticated rear suspension in the class. Its new Uni-Trak single-shock rear suspension and KX-style Kayaba forks provided nearly 10 inches of excellent travel and an all-new 173cc single pumped out a stump-thumping 24 horsepower. With its strong motor, state of the art suspension, and motocross-level chassis, the KDX felt far more serious than most of its rivals. It was a potent machine made for going fast in the woods.

Kawasaki’s all-new KDX175 was at the very cutting edge of suspension design in 1980. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Kawasaki’s all-new KDX175 was at the very cutting edge of suspension design in 1980. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

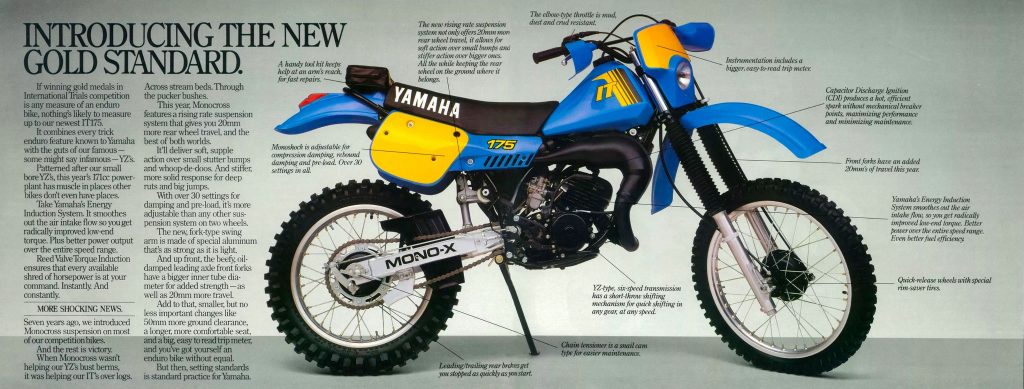

In addition to a new Kawasaki, the PE also had to contend with a completely redesigned IT175 for 1980. After several years of short-legged machines, Yamaha finally upgraded the suspension on the IT to match most of the performance found on the latest YZ125. An all-new monoshock with a huge remote reservoir and external rebound damping adjustability was taken directly off the YZ and paired with a new set of air-adjustable 36mm Kayaba forks. With just short of 10 inches of travel front and rear, the new IT was right back in the ballpark with its rivals.

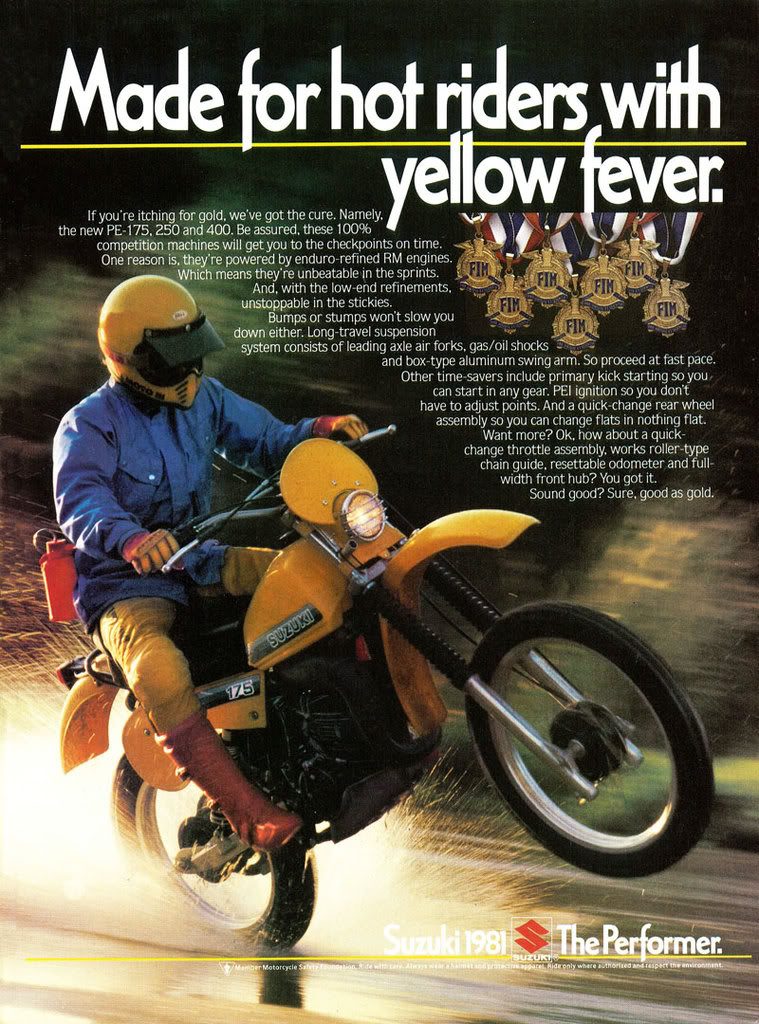

Not content to get blown off the trail in 1980, Suzuki was also back with an all-new 175 designed to go toe-to-toe with its Enduro competition. Visually, the bike was largely unchanged aside from a new set of FIM-legal side plates and a slightly smaller fuel tank (0.4-gallons less than 1979). These changes improved the PE’s

ergonomics and freshened up its appearance. While the new side plates did give the bike more of an “RM look,” the jury was still out in 1980 whether this was actually an improvement over the old machine’s more purposeful appearance.

Major improvements to chassis strength and power highlighted the PE’s 1980 redesign.

Major improvements to chassis strength and power highlighted the PE’s 1980 redesign.

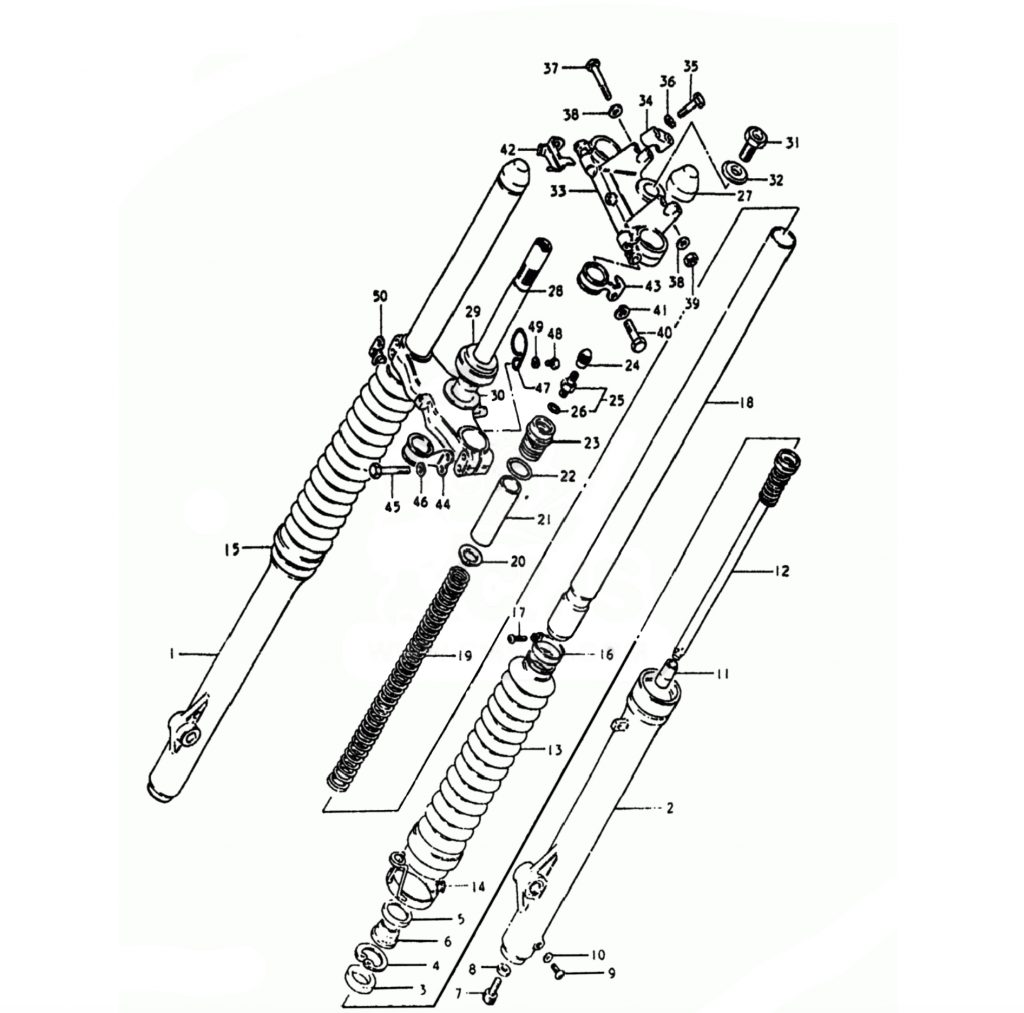

Underneath the slightly stale bodywork, there was an all-new chassis that maintained the dual-shock arrangement of ’79 but added a beefy alloy swingarm and all-new Kayaba shocks that upped the travel to 9.7-inches. The front forks were also new and added air adjustability for the first time. Travel was increased 0.74 inches for a total of 9.84 inches of available movement. This put it right in line with the all-new IT and KDX. The chassis’ geometry was altered for 1980 to improve the PE’s steering response; while most riders liked the old bike’s handling, some had complained of a bit of a front-end push in loose conditions. Overall chassis strength was greatly increased as well with a move away from mild steel of previous PEs to the same chromoly steel used on the RM line. With the move to larger forks, the steering stem was also enlarged to better handle the forces the longer travel was likely to subject the frame to.

In the late seventies and early eighties Suzuki was aggressively involved in the Enduro market, capturing several gold medals in international competition. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the late seventies and early eighties Suzuki was aggressively involved in the Enduro market, capturing several gold medals in international competition. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Complementing the revised chassis was a completely redesigned motor for 1980. In an effort to get the PE out of the horsepower doghouse the Suzuki engineers ditched the complete top end of the ’79 machine and bolted on an all-new cylinder and head for 1980. The exhaust system was redesigned as well and tuned to allow the PE to breathe better without being too obnoxious on the sound front. The bore, stroke, and displacement remained unchanged at 62.0 x 57.0mm for a total of 172cc.

All-new forks for 1980 increased travel and added air caps to offer an additional level of trail-side tunability. Photo Credit: Suzuki

All-new forks for 1980 increased travel and added air caps to offer an additional level of trail-side tunability. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the dyno, all of those changes added up to a massive 25% increase in horsepower over 1979. The redesigned engine pumped out 4.56 more horsepower at its peak and even outclassed the RM125 in 1980. That put it right up there with powerhouses like the KDX and easily outpaced the rather disappointing power plant in the redesigned IT175. Low-end response was improved for ’80, with the Mikuni carburetor offering much cleaner jetting than the year before. The PE was still no stump-puller, but it was more than adequate to power you through the tight sections. Both the midrange and top-end were greatly improved with the PE no longer falling off a power cliff when revved. This made it much easier to catch the next gear on long climbs and mitigated the annoying hesitation previous PE’s had suffered from when shifting to the upper gears under a load.

An all-new frame for 1980 offered more aggressive geometry and a major upgrade in strength through the use of tough chromoly steel. Photo Credit: Suzuki

An all-new frame for 1980 offered more aggressive geometry and a major upgrade in strength through the use of tough chromoly steel. Photo Credit: Suzuki

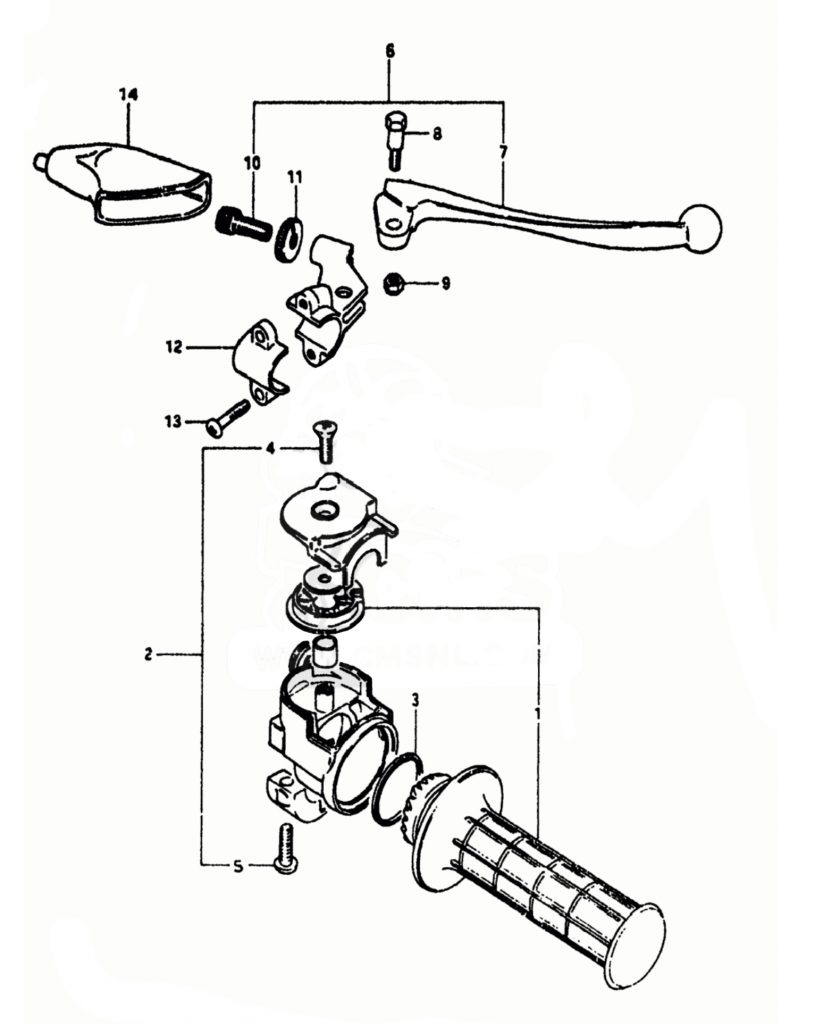

On the chassis side, the PE was also improved but the competition was quickly surpassing the limits of its less-sophisticated suspension. Both the forks and shocks were stiff and harsh compared to the ultra-plush Kawasaki and trail-gobbling IT. The bulging dual shocks also detracted from the feel of the PE when compared to the slim mono layouts found on the other two. New items like the side-pull throttle and improved quick-change wheel were appreciated, but the continued lack of a folding tip on the levers was starting to feel like a plot to support the aftermarket by 1980. With its newfound power, it was once again a contender, but if you were looking for the best 175 available in 1980 the smart money was on green.

A new Gunner Gasser-style “whirlpool” throttle and a set of split perches were all welcome additions to the PE in 1980. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A new Gunner Gasser-style “whirlpool” throttle and a set of split perches were all welcome additions to the PE in 1980. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Major handling and power gains for 1980 were offset slightly by a step back in suspension performance. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Major handling and power gains for 1980 were offset slightly by a step back in suspension performance. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

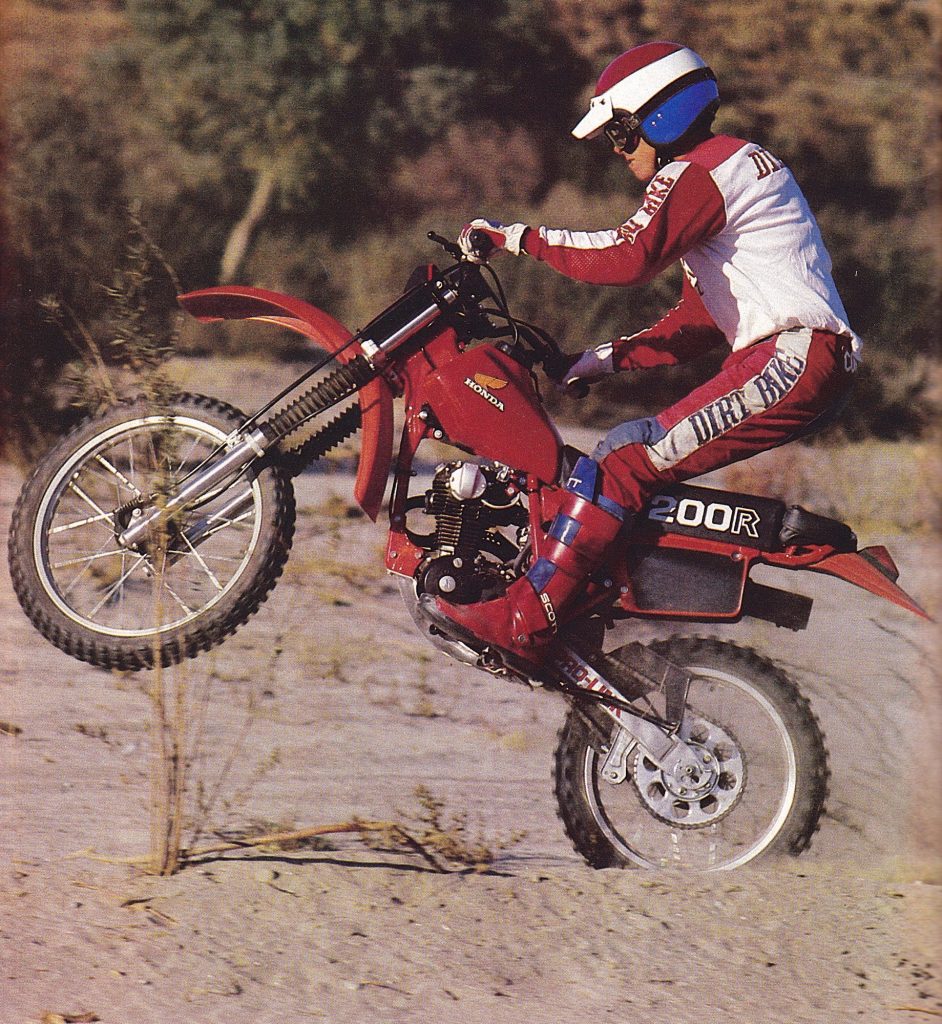

For 1981, the PE175, KDX175, and IT175 were all back with only minor updates. All three featured an array of refinements but no major changes. In the small-bore Enduro class, the only really big news was the arrival of Honda’s all-new Pro-link XR200R. While still down significantly on power compared to its rivals, the new XR offered one of the most advanced chassis in the class in ’81. Its Pro-Link suspension and gutsy motor made it a viable Enduro mount in the tighter Eastern events and the little XR started to garner quite a cult following among those who prized reliability and ease of use over outright power.

A slight change in graphics and the deletion of a skid plate were the only obvious visual changes to the PE175 for 1981. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A slight change in graphics and the deletion of a skid plate were the only obvious visual changes to the PE175 for 1981. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In the case of Suzuki’s PE175, most of its changes for 1981 were not apparent to the naked eye. Aside from a slight tweaking of the graphics and the deletion of a skid plate, the ’80 and ’81 models appeared virtually identical. Instead of a skid plate, ‘81 PE owners received a set of bash bars welded to the frame. These were lighter and less prone to becoming clogged with mud but afforded much less protection to the bottom of the motor. Depending on the type of riding you were doing this may or may not have been an issue.

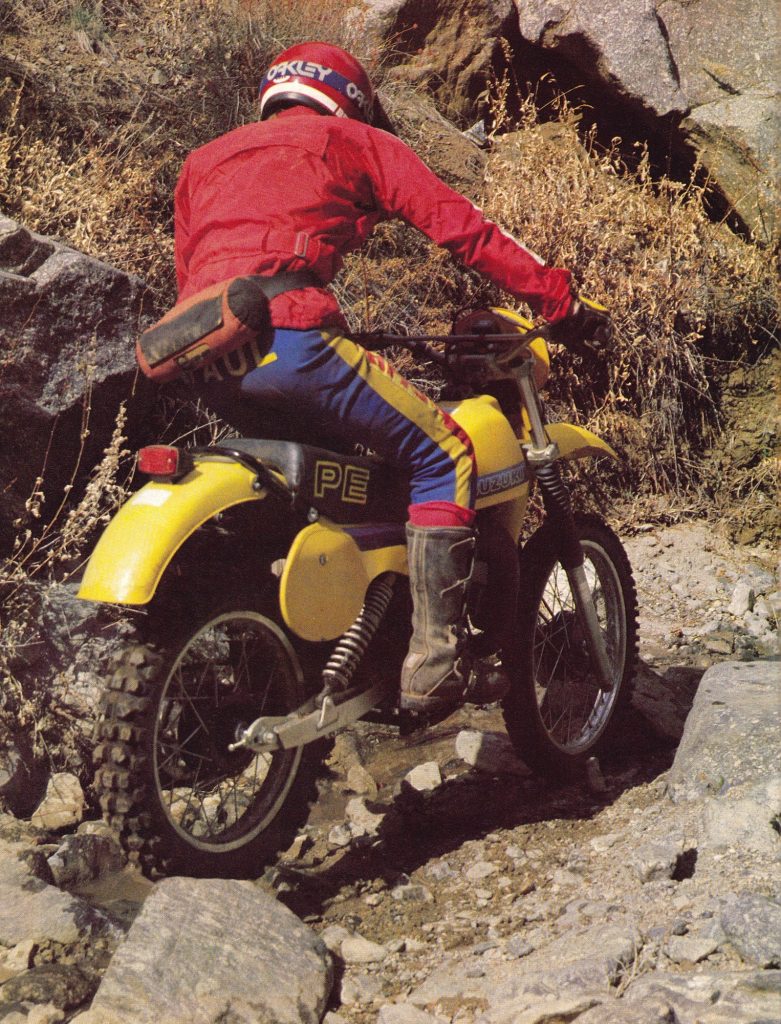

With smooth power and a nimble chassis the 1981 PE175 made an excellent rock-hopper. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With smooth power and a nimble chassis the 1981 PE175 made an excellent rock-hopper. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Other than the deletion of the skid plate the most significant changes for the ’81 model year were a 1mm lowering of the exhaust port, a thicker head gasket, and another minor revision of the exhaust system. The jetting was also leaned out slightly to match the new porting and a set of split perches were added to aid servicing. On the chassis front, there were no changes for 1981. This meant the PE still used the same non-adjustable gas-charged dual shocks and 36mm air/oil-assisted front forks. As in 1980, these units were rather stiffly sprung and harsh on small rocks and roots. This made the PE more suitable for western work but detracted from its appeal as an Eastern machine. Both the KDX and IT offered a smoother ride that was more comfortable on the trail.

Suzuki’s excellent quick-change wheel assembly remained the best system in the class in 1981. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Suzuki’s excellent quick-change wheel assembly remained the best system in the class in 1981. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the engine front, the PE remained a solid performer. As in 1980, the KDX was the powerhouse of the class but the PE was closer than ever. The minor motor mods beefed up the low-end slightly and the mill was even more responsive than before. Snappy, torquey, and reasonably powerful, it was an excellent Enduro power plant.

An all-new Pro-Link XR200R for 1981 upped the suspension game in the small-bore Enduro class. As with previous XRs, it remained a great tight woods machine that suffered once the trail opened up and its competitor’s power advantage came into play. Photo: Dirt Bike

An all-new Pro-Link XR200R for 1981 upped the suspension game in the small-bore Enduro class. As with previous XRs, it remained a great tight woods machine that suffered once the trail opened up and its competitor’s power advantage came into play. Photo: Dirt Bike

With its short wheelbase and aggressive geometry, the PE continued to handle well in the trees but suffered somewhat at speed compared to the longer and better suspended KDX. Neither machine was really the hot setup for bombing across the desert but if the occasional Hair and Hound was in your future you were likely to be happier on the green machine. By 1981, the bodywork and overall feel of the PE were also starting to show their age. The wide and square tank, short seat, and bulging side plates all felt old-fashioned compared to the more modern Honda and Kawasaki layouts. No one particularly liked the bend of the bars as well but that was a pretty easy fix. Overall, the PE was a great seventies machine up against eighties competition. It made a decent racer and fun play bike but if winning was your aim there were once again better machines available in 1981.

Big changes for 1982 included an all-new chassis that incorporated Suzuki’s renowned Full Floater single shock rear suspension for the first time. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Big changes for 1982 included an all-new chassis that incorporated Suzuki’s renowned Full Floater single shock rear suspension for the first time. Photo Credit: Suzuki

For 1982, Suzuki decided to contract its U.S. PE lineup by discontinuing both the PE250 and PE400. Apparently, neither model had proven as popular as the 175 in America so Suzuki decided to put all of their eggs in the smaller machine’s basket for ’82. Thankfully, with this renewed focus came a much-improved machine.

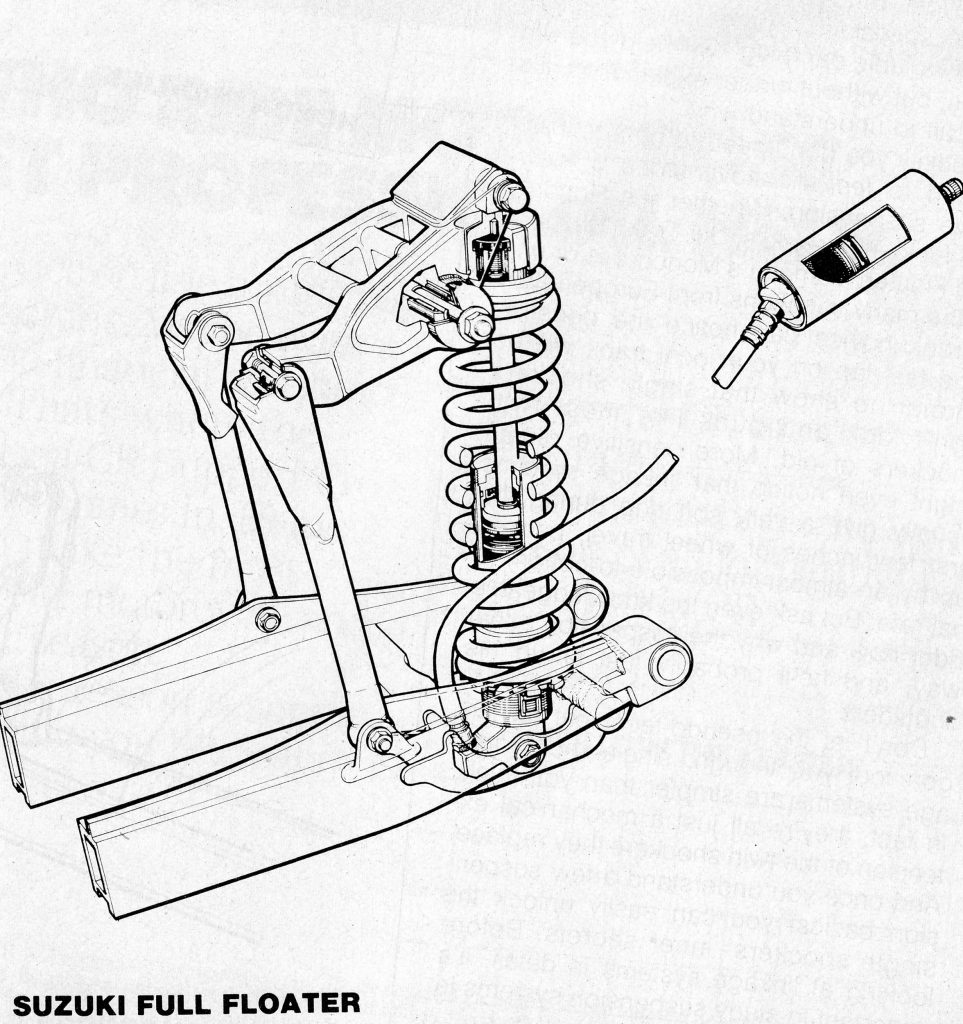

Suzuki’s original Full Floater system was unique for its use of two linkages to isolate the shock and allow it to “float” independently from the rest of the chassis. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Suzuki’s original Full Floater system was unique for its use of two linkages to isolate the shock and allow it to “float” independently from the rest of the chassis. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In terms of competition, the PE’s main foes for 1982 remained the Kawasaki KDX175 and Yamaha IT175. After taking the crown of the top 175 in 1981, the KDX was back with only minor changes while the Yamaha marched into 1982 with an all-new design. The loveable XR200R was back as well, but Bold New Graphics and some minor damping updates were not enough to overcome its relative lack of power compared to its rivals.

Yamaha’s IT175 joined the PE with a major upgrade for 1982. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Yamaha’s IT175 joined the PE with a major upgrade for 1982. Photo Credit: Yamaha

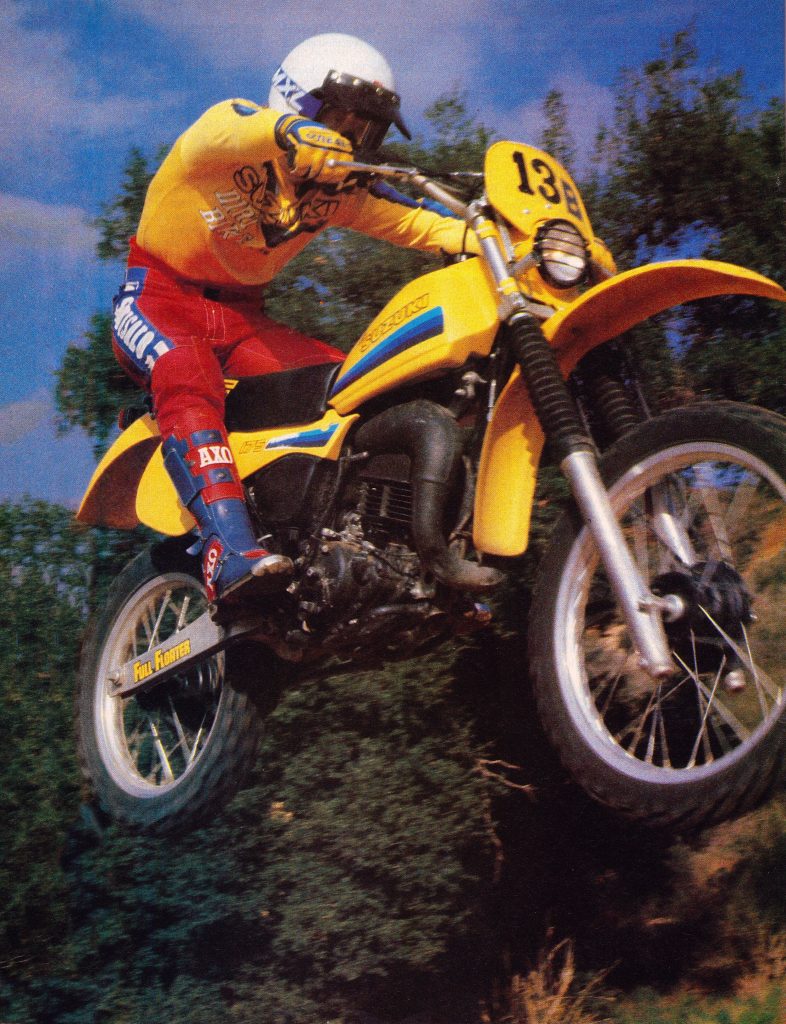

In the case of the PE, Suzuki came to the plate in 1982 with a complete redesign of the chassis on their 175 Enduro. This all-new design incorporated Suzuki’s revolutionary Full Floater rear suspension system for the first time and finally brought the PE up to date with its single-shock rivals. Introduced in 1981 on the motocross line, the Full Floater consisted of a large single damper connected to the frame and swingarm by a set of pull rods and linkages. By having a linkage at both the top and bottom of the shock, the Full Floater allowed the shock to be isolated from the rest of the chassis and “float” independently. In Suzuki’s estimation, this design would allow the suspension to be more responsive by keeping the angle of the shock consistent thus preventing binding as it moved through its travel. In 1981, the RM’s Full Floater suspension had proven to be the best-performing of the new linkage-equipped systems so its appearance on the PE175 was a welcome addition.

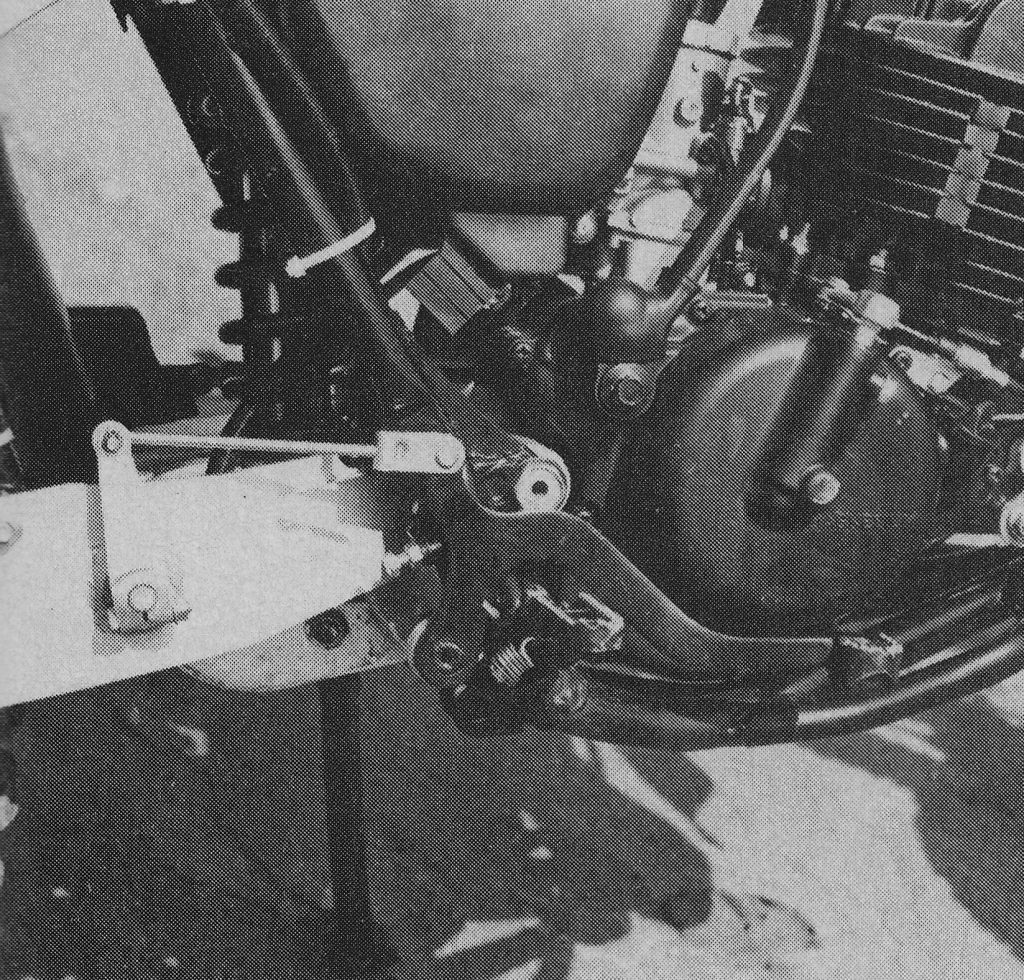

In order to allow the rear wheel to be removed without messing with the brake assembly, the Suzuki engineers had to design a unique crossover linkage that connected the lever on the right with the brake on the left. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In order to allow the rear wheel to be removed without messing with the brake assembly, the Suzuki engineers had to design a unique crossover linkage that connected the lever on the right with the brake on the left. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The PE’s new frame was once again constructed of tough chromoly steel and featured a slightly steeper geometry for 1982. To improve steering precision the angle of the head was pulled in from 29.5 degrees to 28 degrees and the diameter of the forks was increased from 36mm to the same 38mm found on the RM125. The new forks provided 10.6 inches of travel and offered air caps as their only external adjustment. In the rear, the all-new Full Floater offered the same 10.6 inches of movement as the front forks with external adjustments for spring preload and four selectable rebound settings. To further improve handling and overall feel, the PE’s rider compartment was redesigned for ’82 with a longer saddle and slimmer seat and tank. This made it easier to slide forward to weight the front wheel in turns and aided comfort on long rides. New straight-pull hubs were taken from the motocross line to increase wheel strength and improve braking feel. As in 1981, the rear wheel offered Suzuki’s excellent quick-change capability.

On the motor front, most of the improvements were due to the PE’s redesigned airbox. The new box offered a larger overall volume and improved breathing for 1982. Internally, the only changes to the motor were new ratios for third through sixth gear. All three were lowered slightly in hopes of reducing the bog riders had complained about on previous PEs when selecting taller gears under a load. To compensate for the new lower ratios, the final drive was altered as well with a switch from 48 teeth to 46 for the rear sprocket.

New bodywork for ’82 maintained the PE’s familiar looks but improved the ergonomics with a longer seat and slimmer layout. Photo Credit: Suzuki

New bodywork for ’82 maintained the PE’s familiar looks but improved the ergonomics with a longer seat and slimmer layout. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the trail, all of these changes added up to an all-new experience on the PE175. Overall motor performance was improved slightly, but the new gearing was too tall for anything other than wide-open trails. In the woods, first and second were too tall now and the bike responded much better if you went back to the ’81 machine’s larger rear sprocket. Once this was done, the PE offered the Goldilocks version of an Enduro powerband. It did not have as much grunt as the KDX or as much rev as the IT, but it offered the best midrange and just enough at the extremes to make it one of the best do-it-all engines in the class. As with previous PEs, the shifting remained rather notchy but the new ratios made better use of the bike’s available power. Overall it was an excellent small-bore Enduro motor.

With a strong motor, nimble chassis, and excellent suspension, the PE175 was one of the most competitive Enduro mounts available in 1982. Photo Credit: Cycle World

With a strong motor, nimble chassis, and excellent suspension, the PE175 was one of the most competitive Enduro mounts available in 1982. Photo Credit: Cycle World

On the handling front, the PE was once again excellent for woods use. The new chassis gave the bike RM-like manners that were an improvement in every way over 1981. The PE turned very well and could cut under every other machine except the super-short-wheel-based XR. The new larger forks and beefed-up frame also gave the bike a very solid feel that was confidence-inspiring at speed. The fork’s performance was excellent for most riders but really fast guys might have found them a bit too soft. For them, an increase in the oil level helped immensely. Out back everyone loved the performance of the new Full Floater suspension. As on the RMs, the Full Floater PE could be charged into obstacles that would give men on lesser machines pause. It gobbled up logs and roots with ease and absorbed whoops with nary a whimper.

While certainly not a motocrosser, the PE’s class-leading suspension made occasional flights a no-drama experience. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While certainly not a motocrosser, the PE’s class-leading suspension made occasional flights a no-drama experience. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

After two fairly disappointing outings in ’80 and ’81, the PE175 was officially back in contention with a majorly improved ‘82 machine. Nice features like the simplest quick-change wheel assembly, on-the-fly brake and clutch adjusters (super trick stuff in 1982), and a set of (finally!) folding brake and shift levers made the bike one of the most race-ready machines in the class. Once you geared it down and dialed in the forks, the ‘82 PE175 was easily the best Suzuki Enduro offering since the original in 1978. Of course, it still shed bolts at an alarming rate (Loctite everything or plan to go parts hunting), was no longer a lightweight (at 230 pounds it tied the XR for the most portly machine in the class), and offered brakes that were useless in water, but in terms of outright performance, the 1982 PE175 was a major step forward for the brand.

Revised graphics, yellow forks, a blue seat and some gearing changes were the only significant updates the PE received in 1983. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Revised graphics, yellow forks, a blue seat and some gearing changes were the only significant updates the PE received in 1983. Photo Credit: Suzuki

After the complete redesign in 1982, the PE175 was back for 1983 with a modest list of updates. Visually, the bikes were very similar with slightly updated graphics, a new blue seat, and yellow lower fork stanchions being the main giveaway that you had the latest model. In terms of actual performance, the only significant changes were another rejiggering of the transmission’s internal ratios and a switch back to the lower final drive ratio of 1981. This was done to alleviate the clutch frying and bellyaching of riders who had tried to ride the ‘82 machine with the stock gearing and found it a frustrating experience. In 1982, the new straight-pull hubs had proven even more susceptible to water infiltration than the PE’s previously porous designs so Suzuki added a new seal to the hubs for ’83 in hopes of preventing the ’82 model’s disappearing brake issues. Other than these minor updates the PE175 was the same solid performer it had been the year before.

In 1983, the 200 Enduro class was one of the most hotly-contested divisions in off-road racing. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1983, the 200 Enduro class was one of the most hotly-contested divisions in off-road racing. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While Suzuki was content with refinements for 1983, its biggest Enduro competitor was back with an all-new machine designed to bury its off-road competition. In 1982, the KDX175 had maintained its lead as the torquer of the class with a strong bottom-end motor that pulled harder and sooner than its rivals. Compared to the all-new IT and PE, its chassis was a bit outdated but it still made a viable mount for those who did not want to ride the clutch and scream the motor from check to check. For 1983, Kawasaki put those chassis doldrums in the rear mirror with a completely redesigned KDX. Bumping the displacement up to a full 198cc, the rechristened KDX200 romped on its competition with a burly blast of power that easily bested its rivals. The additional displacement gave the bike an advantage at every point on the power curve and made a huge difference in the rideability of the machine. The new chassis was a solid improvement as well but the redesigned Uni-Trak was still not as supple on the trail as the PE’s Floater.

In the right conditions the PE175 remained a competitive Enduro mount in 1983. Photo Credit: 1984

In the right conditions the PE175 remained a competitive Enduro mount in 1983. Photo Credit: 1984

As to the PE, the Full Floater remained the most significant advantage it had over its rivals. The new transmission ratios for ’83 spread out the power but made the bike slower to rev and more tame-feeling. Considering it was not really a rocket to begin with, this was not an improvement. Its 230 pound weight was 15 pounds porkier than the new KDX as well, thus further handicapping its forward thrust potential. As in previous years, the PE was certainly capable of winning in the right hands, but its excellent suspension and solid handling were no longer enough to keep it at the front versus much lighter and stronger competition.

Bold New Graphics and some additional blue paint were the limits of the updates on the PE for 1984. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Bold New Graphics and some additional blue paint were the limits of the updates on the PE for 1984. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1984, the beloved PE175 entered into what would become its swan song season with only a set of new “factory graphics” and a more waterproof throttle to account for its $49 increase in cost over 1983. While the PE was mechanically identical to the year before, the move to blue for the frame and fork boots brightened up the bike’s appearance considerably and gave the illusion that the Suzuki 175 was more changed than it actually was. Aside from the blue paint, there was a new set of yellow plastic guards for the lower forks, which were no longer painted, and some updated graphics. Other than that, the ‘84 PE175 was more or less an ’82 model with slightly different gearing. While that was not necessarily a bad thing, the competition did get decidedly steeper in 1984 with a complete redesign for the IT and XR. Both machines were greatly upgraded with a bump in displacement bringing the IT up to 200 status for 1984. This left the PE with the smallest motor and oldest chassis in the class. While neither of these detracted from its fun factor, it was clear that Suzuki was no longer interested in continuing to develop its Pure Enduro line. After seven years of production, the fun and feisty PE175 was finally put out to pasture at the end of the 1984 season.

With the PE175 riding off into the sunset at the end of 1984 it would take five more years for Suzuki to dip their toes back into the Enduro waters with the introduction of the all-new 1989 RMX250. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With the PE175 riding off into the sunset at the end of 1984 it would take five more years for Suzuki to dip their toes back into the Enduro waters with the introduction of the all-new 1989 RMX250. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com