For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at one of the most innovative and unique machines of the late eighties and early nineties, ATK’s 406 two-stroke.

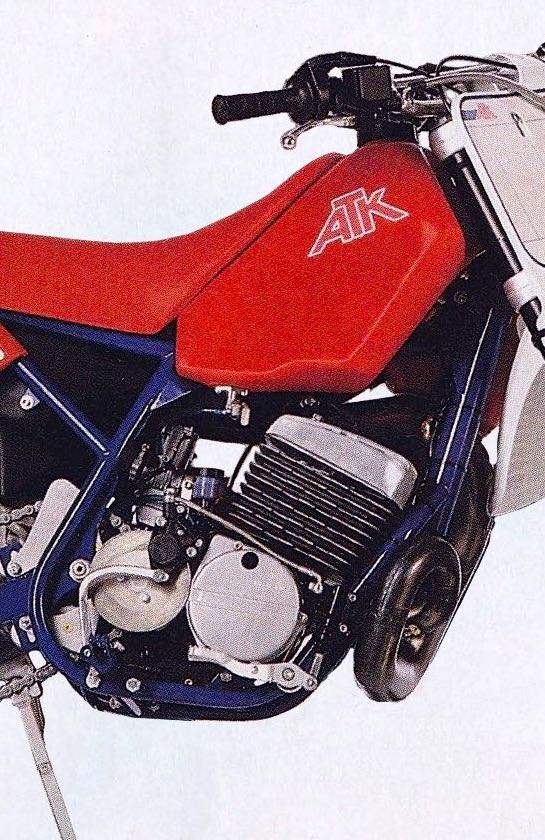

In the eighties and early nineties Horst Leitner’s ATK was one the most innovative brands in the industry. His eclectic lineup of boutique motorcycles combined old-school motor designs with the latest chassis technology to provide a wholly unique riding experience. Photo Credit: ATK

In the eighties and early nineties Horst Leitner’s ATK was one the most innovative brands in the industry. His eclectic lineup of boutique motorcycles combined old-school motor designs with the latest chassis technology to provide a wholly unique riding experience. Photo Credit: ATK

Today, the name ATK is nearly all but forgotten in the world of motocross. Like Maico, Bultaco, CZ, and Can-AM, ATK has faded from a position of prominence to a footnote in the annals of motocross history. Founded by Austrian-born engineer Horst Leitner in the early 1980s, ATK was once the most innovative brand in the sport. A grand Prix motocross racer in the 1960s, Leitner used his racing know-how and inventive mind to create some of the most unique designs of the seventies and eighties. While not all of his forward-thinking ideas have endured, his novel concepts on rear suspension design continue to influence the mountain bike industry to this day.

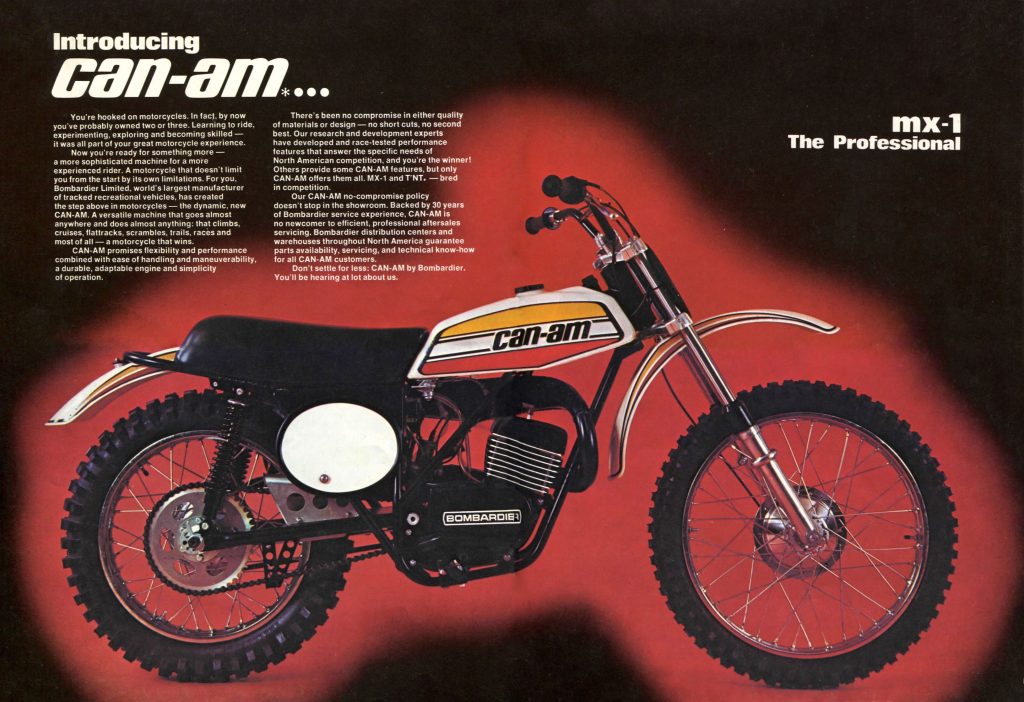

In the 1970s, Rotax motors like the one in this 1974 Can-Am MX-1 were the powerhouses of their respective divisions. For a time, this horsepower advantage was enough to push the poor-handling Canadian machines to the top, but by the early eighties, the new breed of machines from Japan had pushed Can-Am out of motocross prominence. Photo Credit: Can-Am

In the 1970s, Rotax motors like the one in this 1974 Can-Am MX-1 were the powerhouses of their respective divisions. For a time, this horsepower advantage was enough to push the poor-handling Canadian machines to the top, but by the early eighties, the new breed of machines from Japan had pushed Can-Am out of motocross prominence. Photo Credit: Can-Am

As Leitner’s racing career came to a close in the 1970s, he became interested in designing a way to reduce the effects of engine torque on his machine’s rear suspension. At the time, suspension travel was growing by leaps and bounds and engineers were having a difficult time overcoming the many new challenges these long-travel designs presented. Leitner believed that one of the major forces holding back suspension performance was the binding and squatting that occurred once power was applied to the rear wheel. As torque was applied to the rear wheel, the rear suspension compressed and reduced the travel available to deal with track obstacles. This squatting of the rear suspension also affected chassis balance and reduced the traction of the front wheel on the exit of turns. By reducing this squatting effect Leitner believed he could both improve the handing and rear suspension action of any machine.

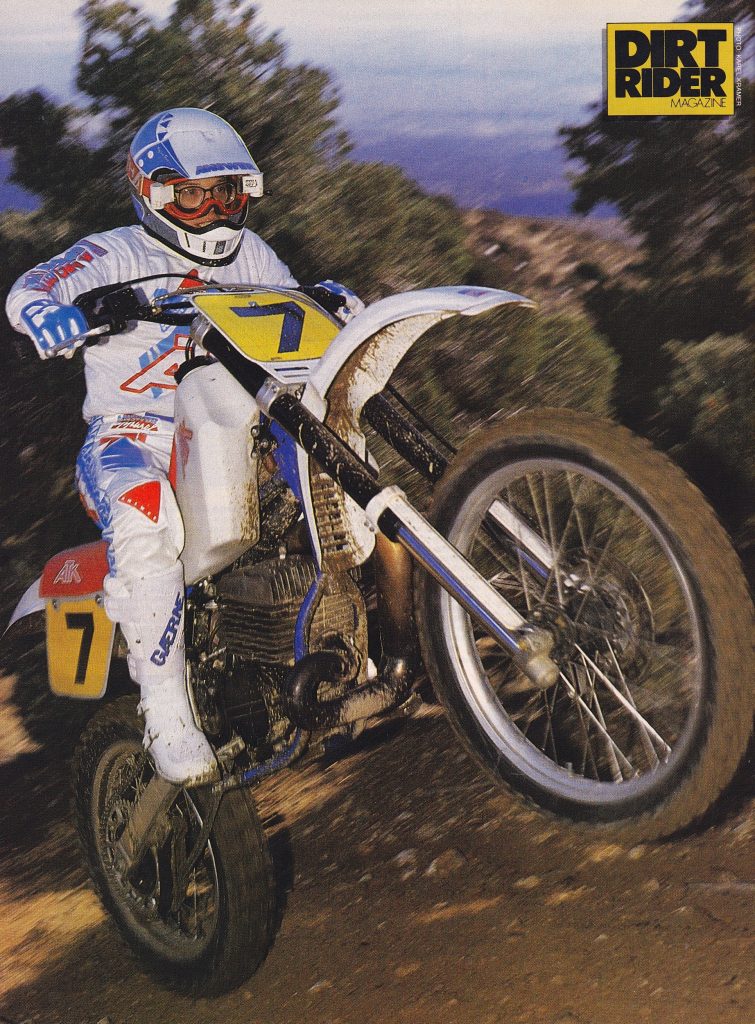

Before venturing into full-scale motorcycle production, ATK made a name for itself by offering a motocross-ready chassis designed to accommodate motors from Honda’s popular line of XR four-strokes. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

Before venturing into full-scale motorcycle production, ATK made a name for itself by offering a motocross-ready chassis designed to accommodate motors from Honda’s popular line of XR four-strokes. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

Patented in 1981, Leitner’s answer was the Anti-Tension Kettenantrieb (from which ATK derived its name), which reduced torque on the rear suspension by rerouting the chain over a pair of rollers above and below the swingarm. Sold commercially as the “A-TraK Torque Eliminator”, the device could be bolted onto street and dirt machines to improve handling and suspension performance.

In 1985, ATK took their motocross project one step further by offering a ready-built version using Rotax’s proven 562cc SOHC four-stroke mill. At $4590, it cost nearly double what a comparable two-stroke from Japan would set you back in 1985, but people snapped them up faster than ATK could churn them out. Photo Credit: ATK

In 1985, ATK took their motocross project one step further by offering a ready-built version using Rotax’s proven 562cc SOHC four-stroke mill. At $4590, it cost nearly double what a comparable two-stroke from Japan would set you back in 1985, but people snapped them up faster than ATK could churn them out. Photo Credit: ATK

After the A-TRAK proved a commercial success, Leitner and his team broadened their sights by developing a complete ready-built chassis that could accept motors from the immensely popular XR350R and XR500R four-strokes. At the time, four-strokes were mostly a novelty in motocross with ancient TT500-powered Pro-Tec Yamahas still garnering much of the racing market. The arrival of ATK’s ready-built racer immediately upped the state of the art in four-stroke motocross design with modern ergonomics and suspension finally available to racers who preferred not to mix their gas and oil.

Made In The USA: While ATKs were fashioned out of components from all over the world, its final assembly in California was a source of pride to many who paid the extra premium the brand commanded. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Made In The USA: While ATKs were fashioned out of components from all over the world, its final assembly in California was a source of pride to many who paid the extra premium the brand commanded. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

Once more, ATK had a hit on their hands, and it was not long before Austrian automobile and motorcycle manufacturer Puch approached Leitner about building an ATK-branded motorcycle. At the time, Puch was out of the motocross business but the manufacturer had enjoyed a brief run of racing success in the mid-seventies with Harry Everts at the controls. Everts and Puch took home the 1976 250 World Motocross Title on an ultra-exotic twin-carbed machine that is still renowned for its blazingly fast motor performance.

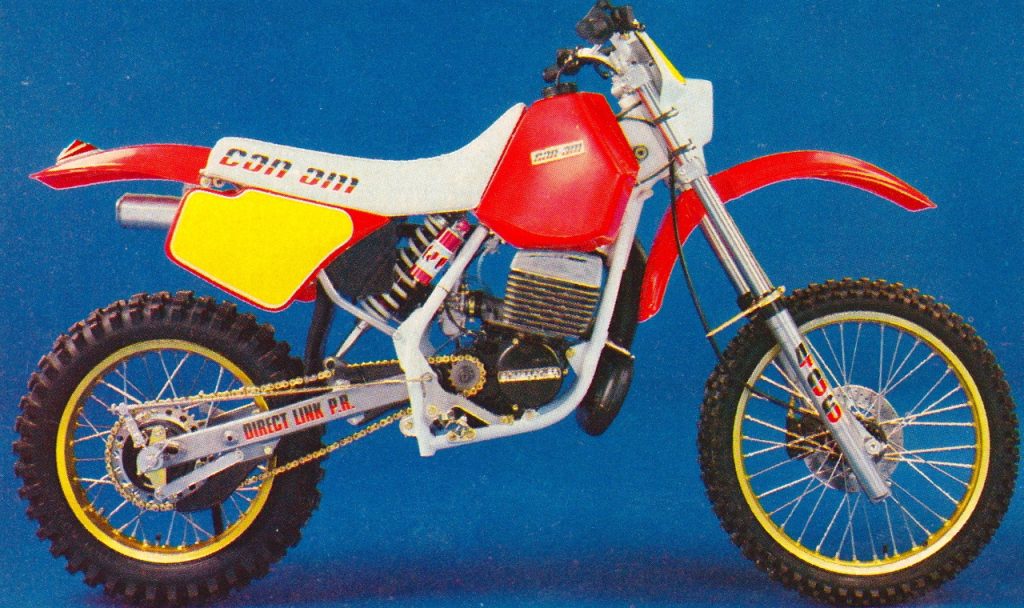

After several years of struggling to sell outdated designs, Can-Am finally stopped production of their two-wheeled lineup after the 1987 season. With a backlog of unused Rotax motors in inventory and a struggling dealer network to satisfy, Can-Am’s parent company Bombardier turned to ATK to develop a pair of new machines they could sell through their existing Can-Am network. Photo Credit: Can-Am

After several years of struggling to sell outdated designs, Can-Am finally stopped production of their two-wheeled lineup after the 1987 season. With a backlog of unused Rotax motors in inventory and a struggling dealer network to satisfy, Can-Am’s parent company Bombardier turned to ATK to develop a pair of new machines they could sell through their existing Can-Am network. Photo Credit: Can-Am

Puch promised backing to get the ATK operation up and running and helped facilitate access to Austrian-built Rotax motors. Throughout most of the 1970s, the name Rotax was synonymous with serious motocross power. Their rotary-valve two-stroke power plants were as much as 20% more powerful than their competitors and renowned for their eye-opening performance. Unfortunately, however, the chassis they were bolted to were rarely up to harnessing their impressive performance.

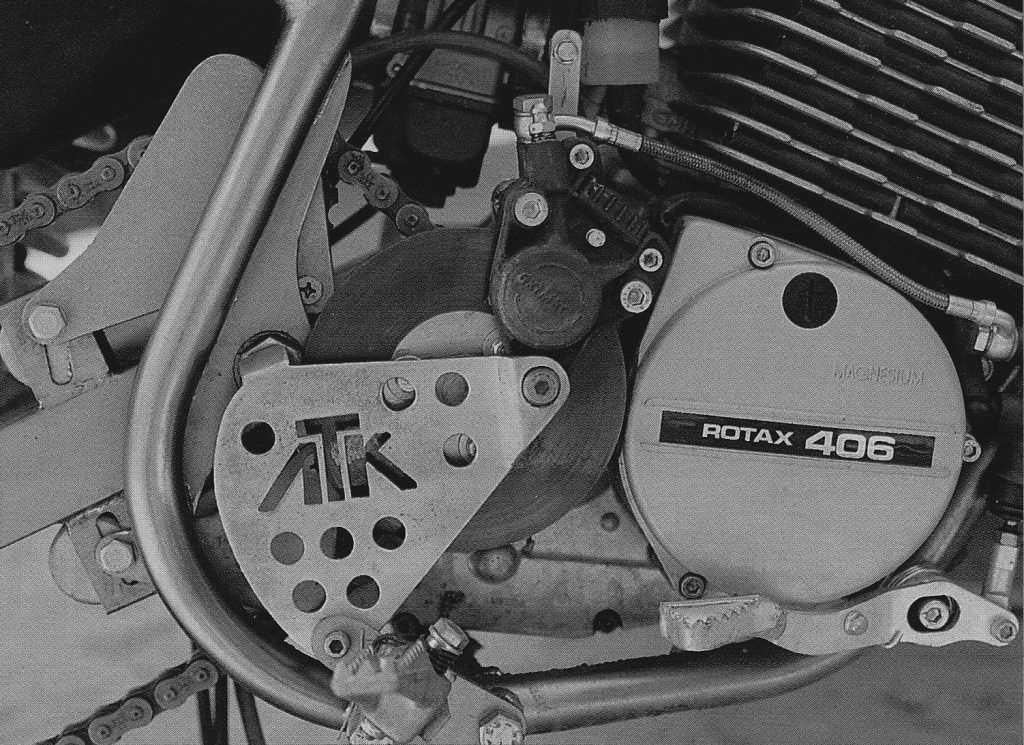

While the chassis on the all-new ATK 406 was at the cutting edge of design, its motor dated back to Can-AM’s 1980 MX-6. While lightweight, rugged, and simple to service, the motor’s utter lack of modern performance features handicapped it against its more powerful rivals. Photo Credit: Bonhams

While the chassis on the all-new ATK 406 was at the cutting edge of design, its motor dated back to Can-AM’s 1980 MX-6. While lightweight, rugged, and simple to service, the motor’s utter lack of modern performance features handicapped it against its more powerful rivals. Photo Credit: Bonhams

By the early eighties, innovations by the Japanese had eclipsed their two-stroke’s performance, but the power of the thundering Rotax thumpers remained unassailed. Because of this and Leitner’s desire to sell a unique and premium machine, the ATK was slated to employ Rotax’s 562cc SOHC four-stroke motor and a built-to-order chassis. Each bike was built specifically to the desires of its owner with a selection of suspension components available. All ATKs featured a link-less rear suspension design and their patented A-TraK anti-torque system. Shock duties were handled by a premium White Power (today known as WP) damper valved to the size, speed, and intended use of the buyer. Up front the customer could choose between a set of 43mm conventional Showa forks or for an additional $195, White Power’s very trick all-new inverted alternatives. Once again, the spring rates and valving would be meticulously set up for each customer before delivery.

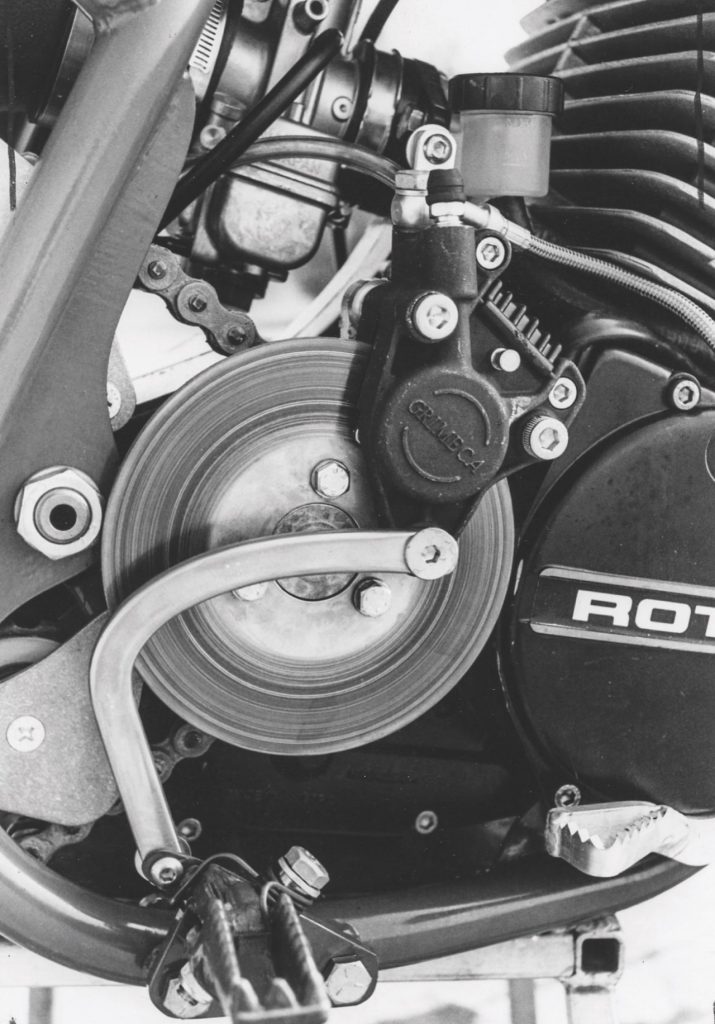

Never afraid to think outside of the box, the engineers at ATK were always looking for innovative ways to secure a performance advantage. By moving the rear brake to the countershaft and reversing the brake pedal, ATK was able to reduce unsprung weight and prevent most damage to the braking system. While the brake was quite effective in most conditions, the unique placement of the disc and the smaller overall size of the braking system led to fading issues under hard use. Photo Credit: ATK

Never afraid to think outside of the box, the engineers at ATK were always looking for innovative ways to secure a performance advantage. By moving the rear brake to the countershaft and reversing the brake pedal, ATK was able to reduce unsprung weight and prevent most damage to the braking system. While the brake was quite effective in most conditions, the unique placement of the disc and the smaller overall size of the braking system led to fading issues under hard use. Photo Credit: ATK

Launched in 1985, the ATK 560 proved to be a tremendous hit with well-heeled buyers looking to race a unique and highly competitive four-stroke machine. With a price tag two to three times that of a typical Japanese 500, the ATK was a premium machine aimed at a very targeted market. Produced in limited numbers (around 200 per season) out of their small Southern California factory, the ATK 560 quickly became one of the most-coveted motocross machines of the mid-to-late eighties.

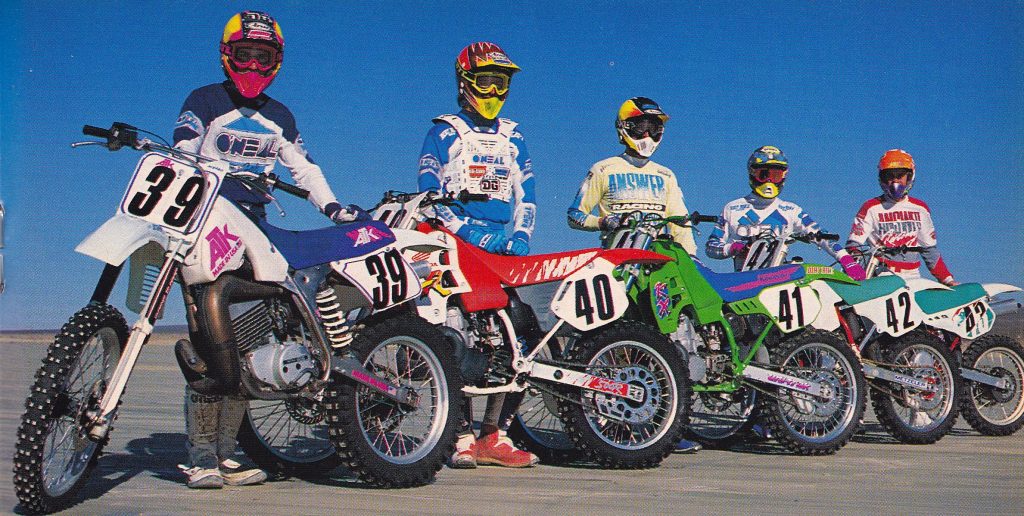

Knowing they were starting with a performance handicap, ATK looked for novel ways to extract more performance out of their 250 and 406 two-strokes. Both machines used ATK’s patented A-TraK system to isolate their rear suspension from engine torque and chose a linkless design to keep weight to an absolute minimum. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Knowing they were starting with a performance handicap, ATK looked for novel ways to extract more performance out of their 250 and 406 two-strokes. Both machines used ATK’s patented A-TraK system to isolate their rear suspension from engine torque and chose a linkless design to keep weight to an absolute minimum. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Just as the ATK was emerging as America’s motocross power, Can-Am was preparing to shut its doors. Owned by Canadian snowmobile pioneer Bombardier inc., Can-Am had been founded in 1971 as an effort to fill out their snowmobile dealer’s summer lineups. Leveraging their ownership of Rotax, Bombardier hit the ground running with a lineup of blisteringly fast machines that immediately scored success on the national and international stage. The new Can-Am motocross and off-road models captured gold in the International Six-Day Trial and took home National Motocross and Supercross titles with riders like Gary Jones and Jimmy Ellis at the controls. With their powerful Rotax motors, the Can-Ams of the seventies were revered for their power and feared for their often-evil handling.

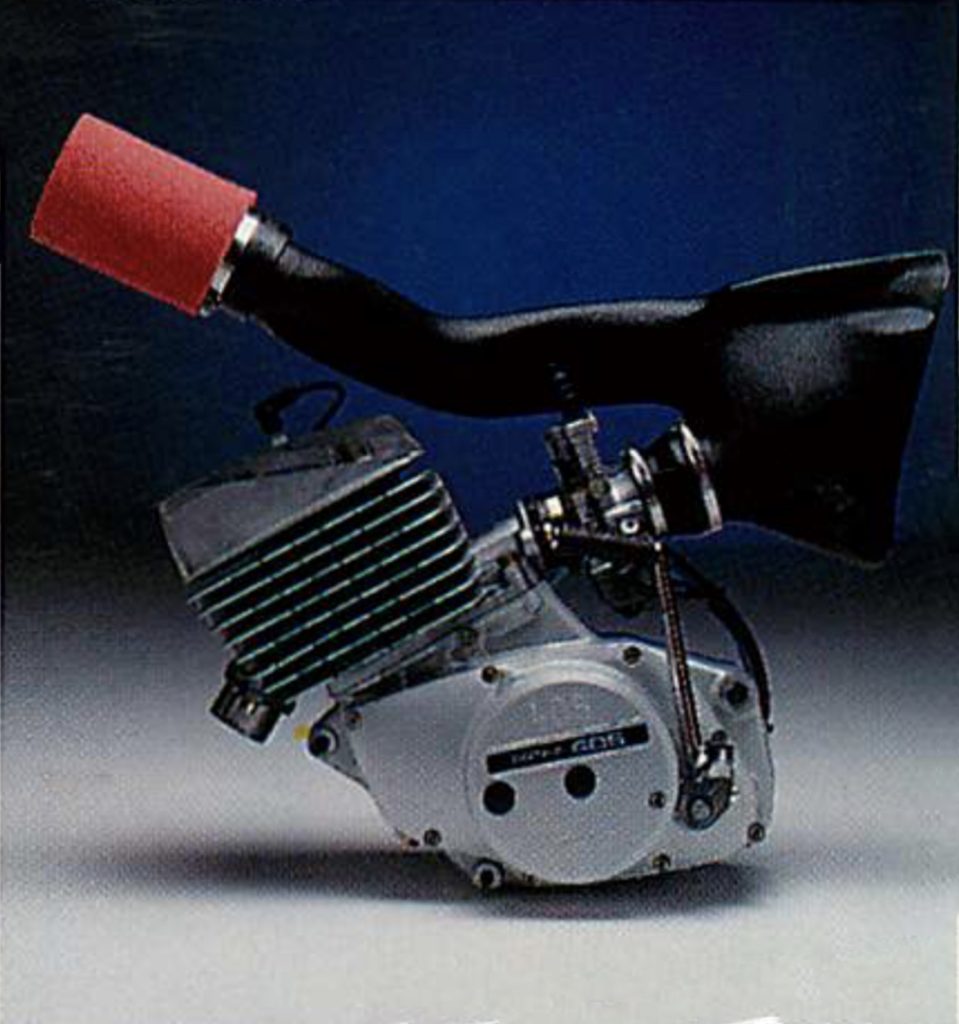

To increase horsepower and improve the off-road utility, ATK designed a unique airbox design for their new two-stroke racers. Both machines placed the air filter up high next to the tank and used a “ram-scoop” arrangement that funneled lots of cool air into the motor. This combined with new porting and a more modern carburetor offered significantly improved performance for the proven Rotax designs. Photo Credit: ATK

To increase horsepower and improve the off-road utility, ATK designed a unique airbox design for their new two-stroke racers. Both machines placed the air filter up high next to the tank and used a “ram-scoop” arrangement that funneled lots of cool air into the motor. This combined with new porting and a more modern carburetor offered significantly improved performance for the proven Rotax designs. Photo Credit: ATK

By the early eighties, however, Rotax’s horsepower advantage had faded and Can-Am was no longer interested in going toe-to-toe with the Japanese. In 1983, Bombardier licensed the brand and outsourced the development of Can-Am to British manufacturer Armstrong/CCM. While this led to more modern designs, the Can-Ams of the 1980s remained largely uninspired performers. By 1987, Bombardier was ready to pull the plug and shut down their motorcycle operation. With the departure of Can-Am, Bombardier’s dealer network was once again left without machines to sell in the warm summer months.

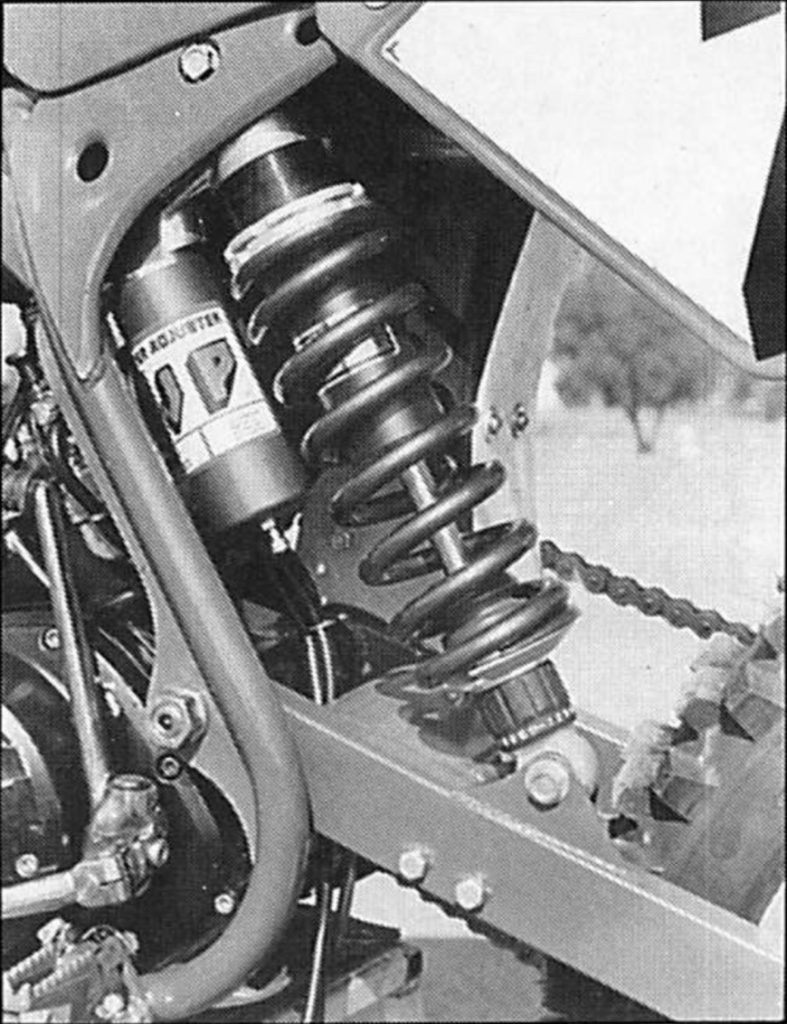

The use of expensive White Power components for the suspension duties set the ATK apart as a premium off-road machine. Photo Credit: ATK

The use of expensive White Power components for the suspension duties set the ATK apart as a premium off-road machine. Photo Credit: ATK

Seeing this as a potential problem moving forward, Bombardier reached out to their American motorcycle partner ATK for a solution. As the supplier of the Rotax motors used on the 560 thumpers, Bombardier already had a relationship with Leitner and his team. Bombardier planned to commission ATK to produce a line of off-road machines based around their aging lineup of air-cooled two-stroke Rotax motors. If successful, this would allow Bombardier to offload a ton of left-over motors and beef up the inventory of their dealer’s stock. Seeing this as an opportunity to further expand his brand, Leitner took on the challenge of turning a decade-old motor into a winning motocross and off-road package.

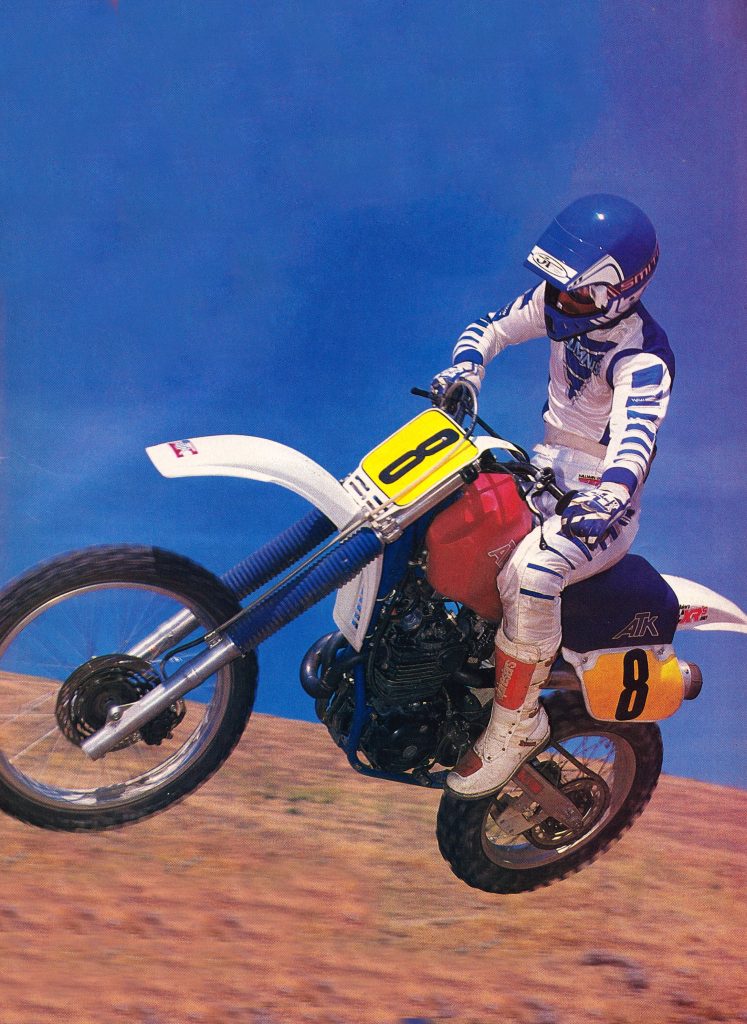

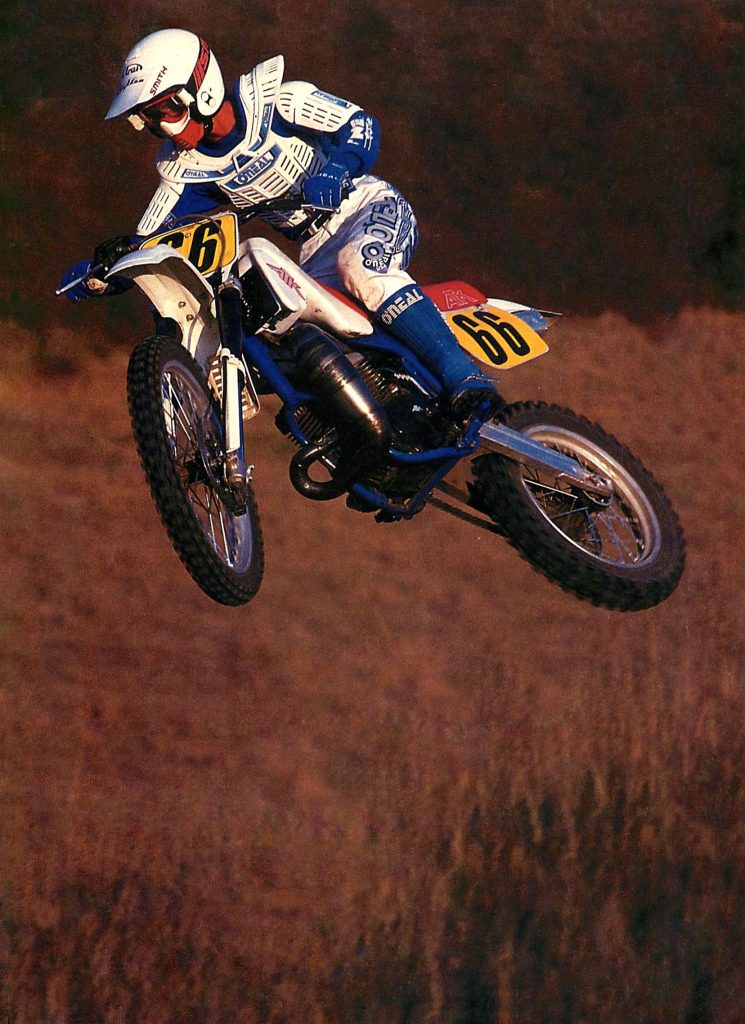

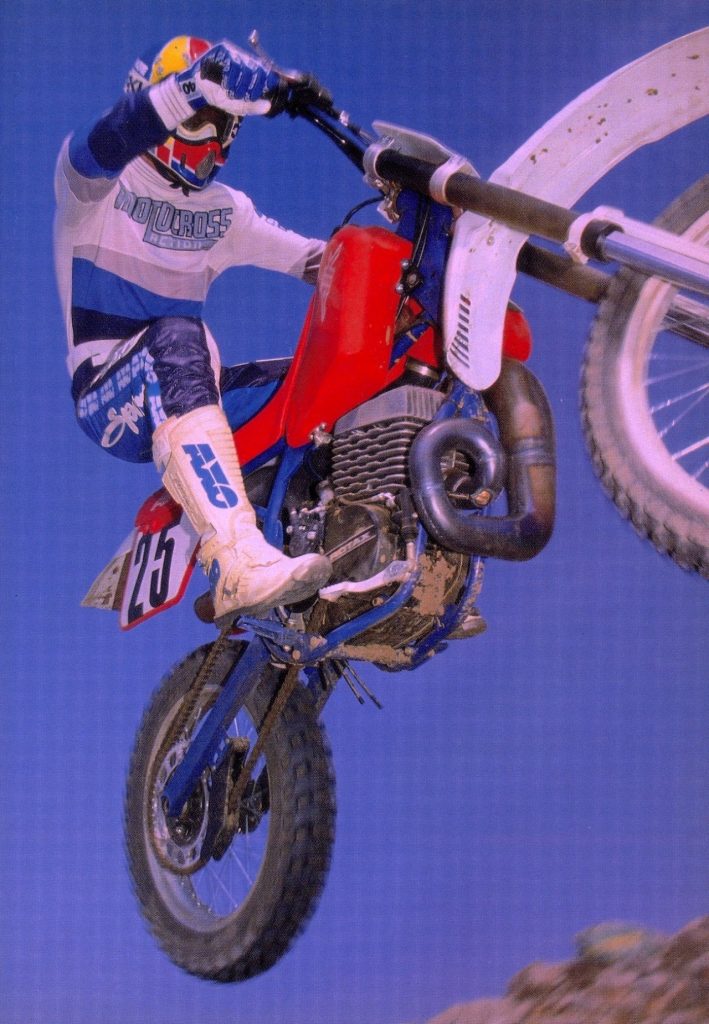

At 215 pounds the 1988 ATK 406 was by far the lightest machine available in the Open class at the time. This light weight paid dividends on the ground and in the air and made the machine one of the easiest-to-handle fliers in the big-bore division. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

At 215 pounds the 1988 ATK 406 was by far the lightest machine available in the Open class at the time. This light weight paid dividends on the ground and in the air and made the machine one of the easiest-to-handle fliers in the big-bore division. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

As with the 560 four-stroke, the true innovation in ATK’s new two-stroke models was its chassis design. By 1988, all of the major manufacturers had moved on to a single-shock rising-rate linkage design for their rear suspension systems. These linkage designs allowed the engineers to develop rear suspension systems that could cope with the small chop and massive hits with equal aplomb. For the ATK, Leitner and his team had focused on simplicity in their rear suspension design. They believed that by using careful shock placement and their patented A-TraK, they could produce better results while saving six pounds and reducing complexity. Knowing their bikes were going to be down on power compared to the competition, the ATK engineers realized that they were going to have to leverage every asset in their arsenal to extract competitive performance.

With only 399cc and no power valve, the ATK 406 was at a pretty steep power disadvantage compared to its Open class competition. Aside from a strong surge in the midrange, its powerband was quite mellow and better suited to off-road riding than hardcore motocross. Photo Credit: Unknown

With only 399cc and no power valve, the ATK 406 was at a pretty steep power disadvantage compared to its Open class competition. Aside from a strong surge in the midrange, its powerband was quite mellow and better suited to off-road riding than hardcore motocross. Photo Credit: Unknown

With that in mind, the ATK team scrutinized every component and rethought conventional wisdom to optimize performance. To reduce unsprung weight, the rear disc brake was downsized and relocated to the countershaft. This both lowered the mass of the wheel and reduced the chance of damaging a rotor. To further lessen the chance of a brake-related failure, the rear master cylinder was relocated to in front of the motor and the rear brake pedal was reversed to point rearward. Because the brake received less cooling air in this position, ATK employed specially insulated pads and a temperature-resistant fluid developed for Formula One car racing to reduce fading.

While the ATK 406 was probably better suited as a do-it-all play bike than a full-time motocross racer, its excellent chassis and high-quality suspension allowed it to turn competitive laps in the right hands. Photo Credit: American Dirt Bike

While the ATK 406 was probably better suited as a do-it-all play bike than a full-time motocross racer, its excellent chassis and high-quality suspension allowed it to turn competitive laps in the right hands. Photo Credit: American Dirt Bike

On the chassis front the ATK was fairly conventional aside from its lack of a rear linkage. The frame tubes were crafted by C&J Racing Frames out of tough chromoly steel and paired with a sturdy alloy swingarm built by Cal Fab. As with the 560 four-stroke, White Power was selected as the suspension supplier with their Super Adjuster shock and 4054 inverted forks handling the track-taming duties. To save development costs, the wheels, hubs, and complete front brake assembly were KTM units with some slight modifications made to accommodate the lack of a rear caliper and slightly different axle sizes employed on the ATK. The bodywork was sourced from Italian plastic giant Acerbis and featured a slim profile that riders appreciated. Being a sort of “do-it-all” machine designed for motocross and off-road use, the new 406 featured a large 2.7-gallon tank that made it more suitable for Enduro and off-road racing.

While the ATK 406 was no beauty, its odd mix of old and new technology and minimalistic bodywork gave the machine a unique visual appeal. Photo Credit: ATK

While the ATK 406 was no beauty, its odd mix of old and new technology and minimalistic bodywork gave the machine a unique visual appeal. Photo Credit: ATK

While the chassis on the new ATK 406 was cutting edge, its motor was anything but. Dating back to the late seventies, this air-cooled two-stroke offered simplicity, light weight, and reliability as its main virtues. Displacing 399cc, the Rotax mill featured a case-reed design that employed a 38mm Keihin for its fuel delivery. To extract more performance, the ATK’s engineers developed a large “ram-air” intake that placed the airbox up high next to the gas tank. This both allowed the machine to draw in the maximum amount of fresh air and increased its ability to ford deep water safely. As was common when the motor was developed, the Rotax mill lacked any sort of variable exhaust port to broaden its power. This simplified maintenance, but further hindered its performance on the track. Aside from new porting, the fancy airbox, and a modern carburetor, the 406’s motor was largely the same as what Can-Am had used on its MX-6 in 1980.

While the ATK 406 was not a superstar on a motocross track, fast off-roaders like National Hair Scrambles champ John Martin (father of current motocross stars Alex and Jeremy Martin) could make it shred in the trees. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

While the ATK 406 was not a superstar on a motocross track, fast off-roaders like National Hair Scrambles champ John Martin (father of current motocross stars Alex and Jeremy Martin) could make it shred in the trees. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

On the track, the ATK was a very different sort of Open class machine. Compared to its 500cc rivals the 406 was positively mellow. Without the benefit of a power valve, the powerband was narrower than Kawasaki’s ultra-broad KX500 and the motor did not hit nearly as explosively as Honda’s shoulder-straining CR500R. Off the line, the 406 was torquey and smooth with its Enduro origins evident in its highly tractable delivery. This meant that riders could be far more aggressive with the throttle without the fear of the machine getting out of sorts or trying to loop over backward. In the midrange, there was a strong surge of power that tapered off noticeably as the machine pulled into the top end. Its best power was to be found in the midrange, but the bike could be revved out in a pinch. In truth, the 406 was only slightly more powerful than a good running 250 and only for a short spurt in the midrange. In 1988, Kawasaki’s broadly powered and burly new KX250 bested the 406 at most points on the dyno curve. The KX was snappier out of the hole and more powerful on top, but 406 was still capable of producing enough power for most situations.

In 1988, the inverted White Power 4054 cartridge forks found on the ATK were the absolute state of the art in suspension design. With proper setup these units provided the best combination of comfort and control in the Open division. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

In 1988, the inverted White Power 4054 cartridge forks found on the ATK were the absolute state of the art in suspension design. With proper setup these units provided the best combination of comfort and control in the Open division. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

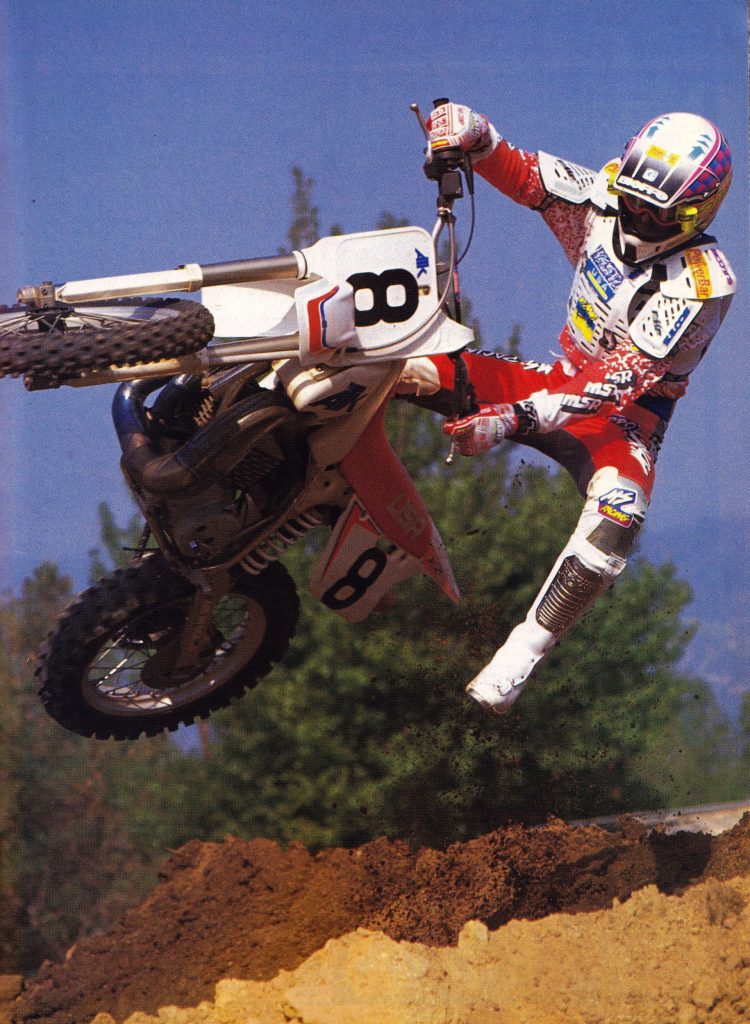

Helping the ATK make the most of its modest power was its light weight and excellent chassis. At 215 pounds it was 20 pounds lighter than most of its 500cc (and some 250cc) competitors and that light feel was apparent on the track. The ATK could be thrown around in a way that would put you on your head on most big bores. It was tossable in the air and nimble on the ground and felt much more like a strong 250 than a ground-pounding 500. This helped the ATK’s pilot keep up his momentum in turns and negate some of the power advantages of the traditional 500s. On the ATK you could keep the power on longer going in and roll it on sooner coming out. By riding the machine more like a 250 than a full 500, the 406 was capable of turning very competitive lap times.

Against the likes of the mighty CR500R and KX500, the mid-sized 406 did not stand much of a chance in any contest of outright speed but much like the modern KTM 350, the 406’s lighter weight and easier to manage power appealed to many riders who found the full-size 500s intimidating. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Against the likes of the mighty CR500R and KX500, the mid-sized 406 did not stand much of a chance in any contest of outright speed but much like the modern KTM 350, the 406’s lighter weight and easier to manage power appealed to many riders who found the full-size 500s intimidating. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the turns, the ATK’s smooth power, light feel, and well-thought-out chassis gave the 406 some of the best handling in the Open class. It was lithe in the corners and admirably stable at speed. There was far less of the headshake that plagued fierce wobblers like the CR500R and better front-wheel traction than the bullet-train-like KX500. It was a great do-it-all-chassis that was as happy turning laps as it was blasting across the desert.

The ATK 406’s light weight made stunts like this one by Jimmy Lewis much less death-defying than they would have been on a traditional 500. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The ATK 406’s light weight made stunts like this one by Jimmy Lewis much less death-defying than they would have been on a traditional 500. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the suspension front, the ATK 406 used premium Dutch components and careful set up to deliver one of the best suspension packages available in 1988. Each machine was individually set up for its intended rider and use case and this allowed the ATK to offer a level of performance not practical on a mass-produced machine. The A-TraK system and careful shock placement allowed the ATK’s engineers to provide a smooth ride that followed the terrain flawlessly in most off-road and track conditions. Without a traditional linkage and with the A-TraK taking out much of the “pop” in the shock’s action, it was not ideal for Supercross-style tracks, but the 406 was never designed to be a stadium machine. Off-road, it gobbled up rocks and logs and on the track, it laughed at chop coming out of turns. Up front, the White Power 4054 inverted cartridge forks were the absolute state of the art in 1988 and performed flawlessly with proper setup. The same units that received poor marks on the KTMs of the time garnered raves on the ATK. Once again, this was due to the individual attention each ATK received.

While certainly innovative, ongoing problems with the countershaft disc brake would lead ATK to abandon it for a more traditional setup in the early 1990s. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While certainly innovative, ongoing problems with the countershaft disc brake would lead ATK to abandon it for a more traditional setup in the early 1990s. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the detailing front, the ATK was excellent in some areas and a work in progress in others. The unique rear brake was popular for its damage resistance but panned for its propensity to overheat. When fresh it worked well, but once it heated up its power went away noticeably. Even with its high-tech fluid and special pads, the lack of cooling air funneled to the disc and its smaller overall size was difficult to overcome when pushed. Up front, the KTM-sourced front binder was likewise a middling performer. It offered decent power and feel but most riders rated it below the Nissin components found on the Japanese machines. The ATK’s unique airbox made the machine a virtual submarine but water and debris could find their way in under certain conditions. Thankfully, this problem would be addressed with a new airbox cover on later 406s. While most riders found the ergonomics comfortable, taller riders did complain that the pegs were too high, and the seat was too low. For those riders, ATK’s optional taller seat seemed to allay most of those issues.

With excellent handling and a strong midrange the 406 was more than capable of rearranging a berm when necessary. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With excellent handling and a strong midrange the 406 was more than capable of rearranging a berm when necessary. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the motor was not particularly powerful, its reliability was legendary. The Rotax motor was nearly indestructible and super simple to work on. Like the YZ490, this made the ATK a perfect mount for adventurers and enthusiasts who were more concerned with making it back to camp than getting there in any real hurry. For most riders, the biggest complaint with the 406’s motor was its old-school European clutch pull which hearkened back to the days when most riders ignored the left-hand lever entirely. While slightly easier to pull than its seventies counterparts due to a new lever ratio, it remained one of the heftiest pulls in the 1988 Open class. The frame, swingarm, seat, aluminum bars, plastic, and switchgear were all above average quality and in keeping with ATK’s intention to market the 406 as a premium machine. At $3895 the 406 cost nearly 25-percent more than its Japanese competitors and it was important that consumers felt they were getting good value for that extra cost.

With excellent suspension front and rear airtime was no problem on the ATK. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With excellent suspension front and rear airtime was no problem on the ATK. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Today, the ATK 406 remains one of the most interesting machines of its era. The product of a convergence of commercial necessity and a little “parts bin” engineering, the 406 turned out to be the jack-of-all-trades Can-Am’s dealers needed. While it was not destined to be a world-beater on the motocross circuit, its exclusivity and unique nature made it hugely appealing to riders looking for something different than the Universal Japanese Motorcycle. Even with its substantial cost premium over the Japanese, ATK sold out every 406 it could make in 1988 before the first machine rolled off the assembly line. Intended as a lifeline to its dealers, the 406 and its stablemates propelled ATK past KTM to fifth place in sales in North America in the early nineties.

Full of innovation and draped in the red, white, and blue, America’s Open class oddball was not for everyone, but for the discerning few who could appreciate its charms it was a unique and highly-versatile machine. Photo Credit: ATK

Full of innovation and draped in the red, white, and blue, America’s Open class oddball was not for everyone, but for the discerning few who could appreciate its charms it was a unique and highly-versatile machine. Photo Credit: ATK

With the departure of Leitner to start AMP Research in 1991, the ATK brand lost the visionary force that had driven it throughout the 1980s. The result of that loss would be a steady decline of the brand in the 1990s. Machines like the 406 would continue in the ATK lineup with minor changes for several years but the days of wild innovation were gone. In the 1980s, Leitner and his team created a brand based on doing things differently and the result of that out-of-the-box thinking was some of the most interesting machines of their time. Bold, brave, and just a bit bizarre, the ATK 406 and its siblings turned out to be machines that were greater than the sum of their parts.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com