For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s all-new KX125 A-6 for 1980.

All-new from the ground up, the 1980 KX125 was one of the most advanced machines in motocross in 1980 Photo Credit: Kawasaki

All-new from the ground up, the 1980 KX125 was one of the most advanced machines in motocross in 1980 Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Today’s Kawasaki is a motocross powerhouse with countless FIM and AMA titles to their credit. Over the last forty years the green machines have regularly found themselves at the front of the standings in multiple classes with excellent machines that captured victory in the magazines and on the track. In the early days of American motocross, however, that was not the case. Throughout most of the seventies, Kawasaki’s presence in the 125 class was all but nonexistent. The KX125s were well respected for their power, but derided for their handling and often an afterthought even to their dealers. Many of their dealers were not interested in carrying off-road machines and in 1977, Kawasaki did not even bother to offer a motocross lineup.

In 1980, Kawasaki’s new Uni-Trak rear suspension system introduced the buying public to the joys and hassles of a linkage-equipped rear suspension system. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1980, Kawasaki’s new Uni-Trak rear suspension system introduced the buying public to the joys and hassles of a linkage-equipped rear suspension system. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1978, the green team reentered the 125 motocross market with an all-new KX125 that proved far more competitive than their previously mediocre offerings. The new limited production KX125A-4 was incredibly trick but nearly impossible to find and little threat to Suzuki and Yamaha’s dominant positions in the 125 market.

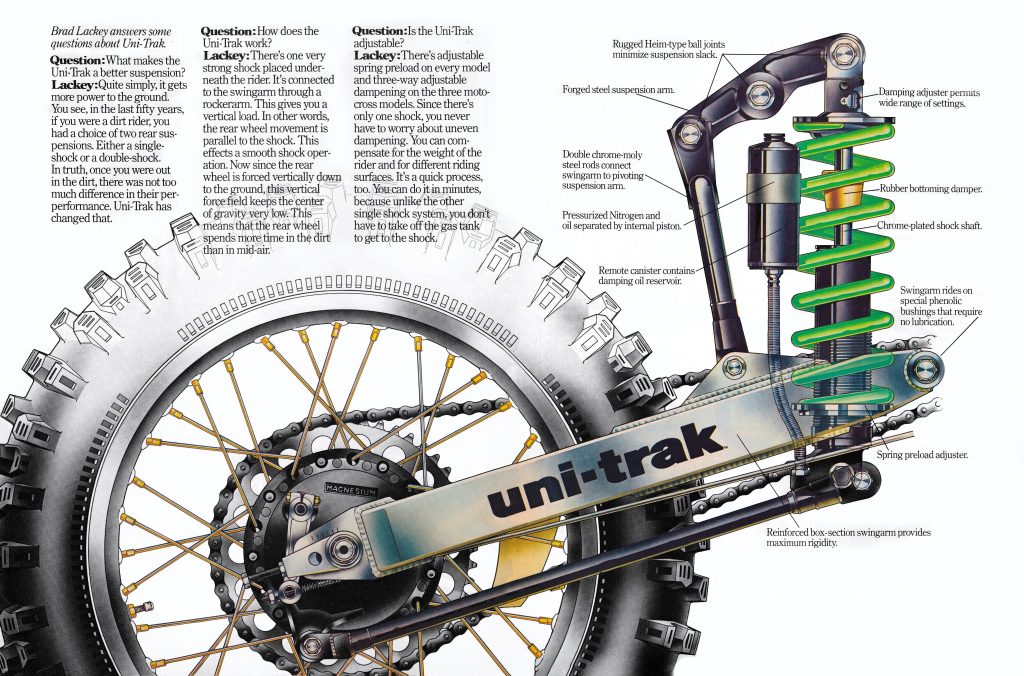

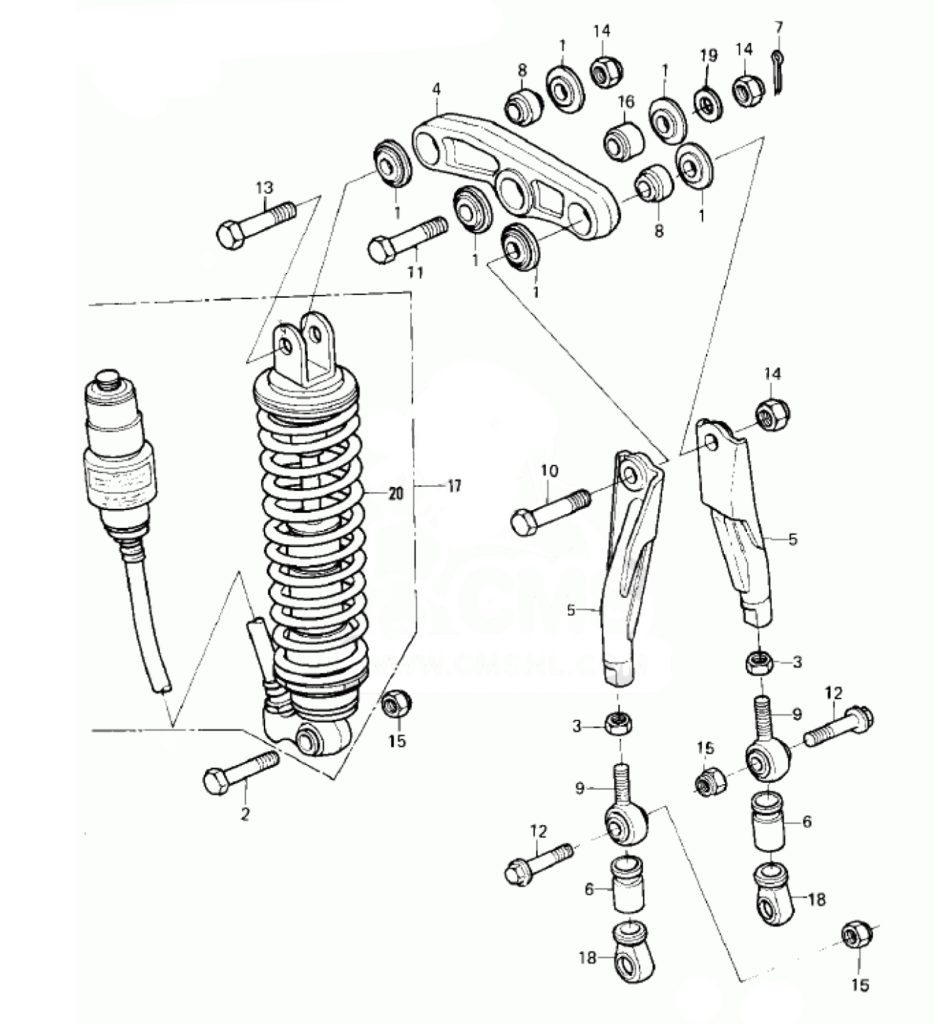

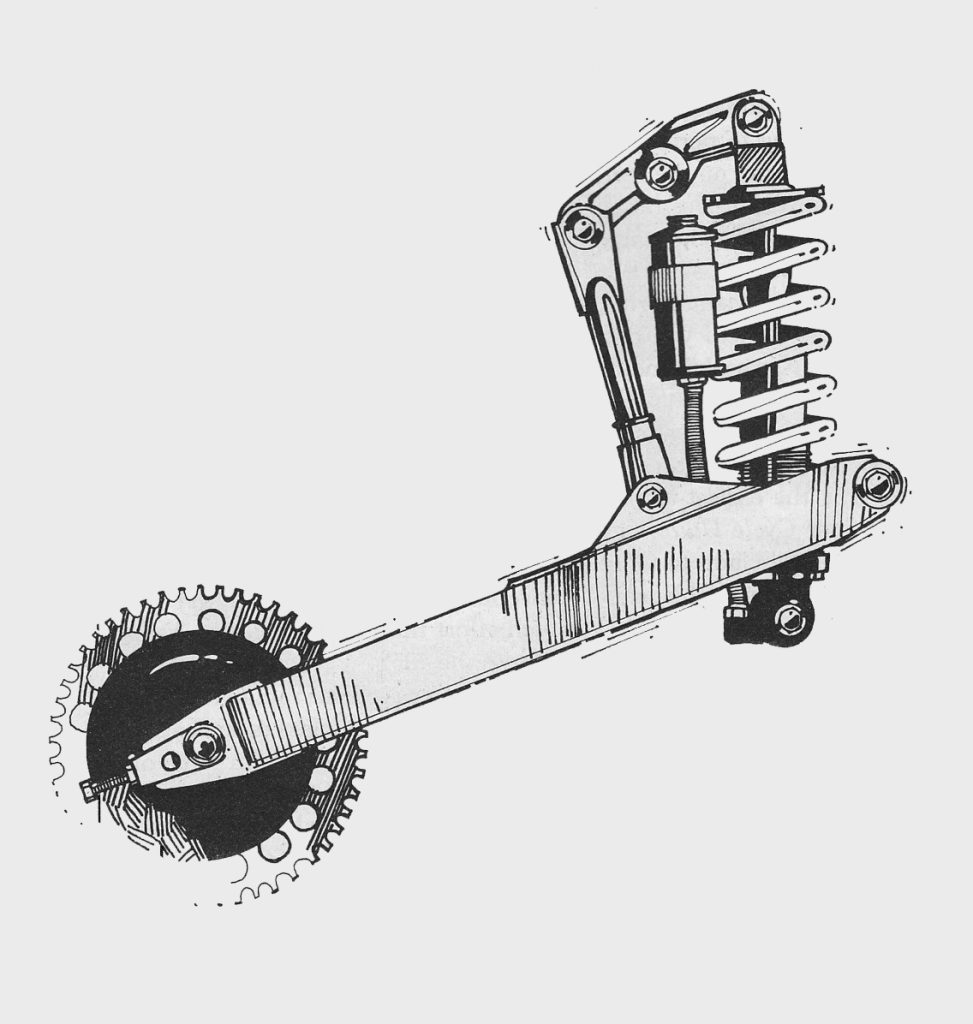

The key component to Kawasaki’s new Uni-Trak system was the large bell crank linkage arm that compressed the single KYB damper. While this first version lacked the rising rate linkage curve of later designs, it still provided a significant step forward in performance over the traditional dual-shock systems of the time. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The key component to Kawasaki’s new Uni-Trak system was the large bell crank linkage arm that compressed the single KYB damper. While this first version lacked the rising rate linkage curve of later designs, it still provided a significant step forward in performance over the traditional dual-shock systems of the time. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1979, Kawasaki was back with another highly regarded but still very limited production 125 offering. The new KX125A-5 brought long-travel suspension and a powerful motor to the class with “works replica” styling that made the Kwacker stand out in a sea of yellow 125 machines. Trick, potent, and thoroughly competitive, the new A-5 signaled that Kawasaki was getting serious about making a dent in the motocross market share of its rivals.

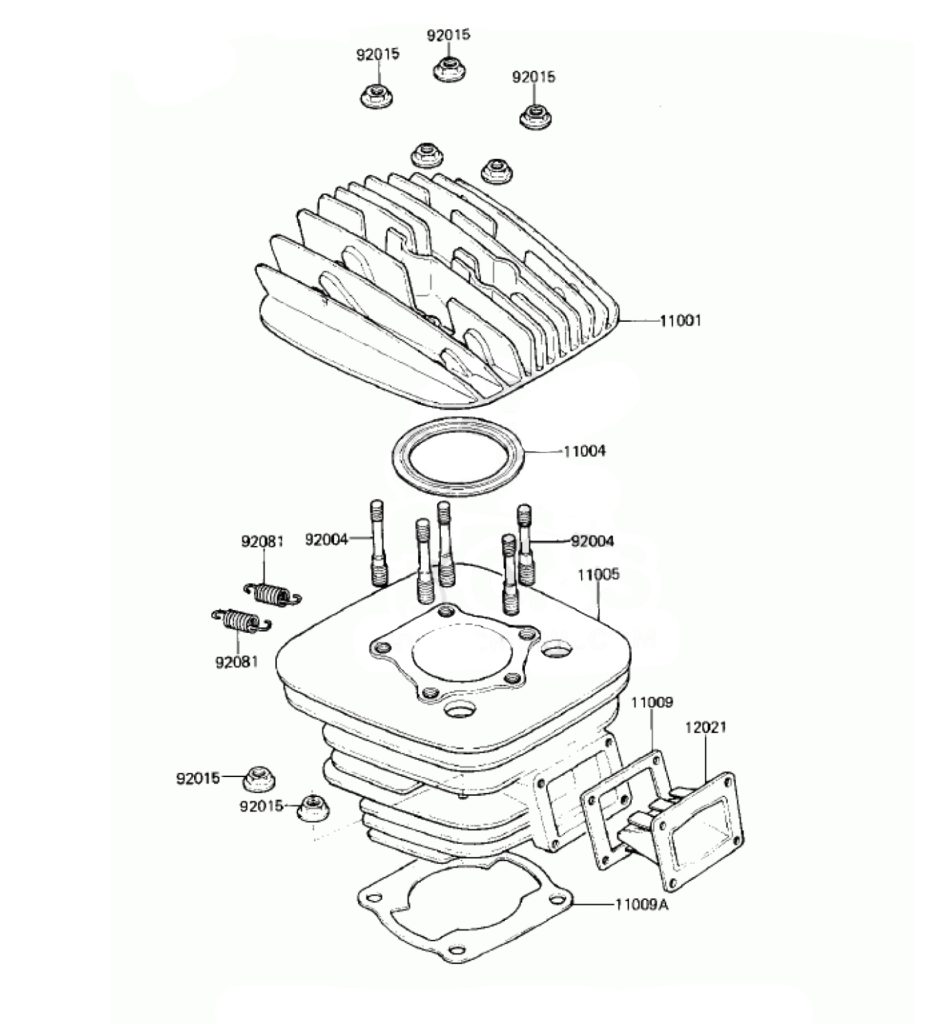

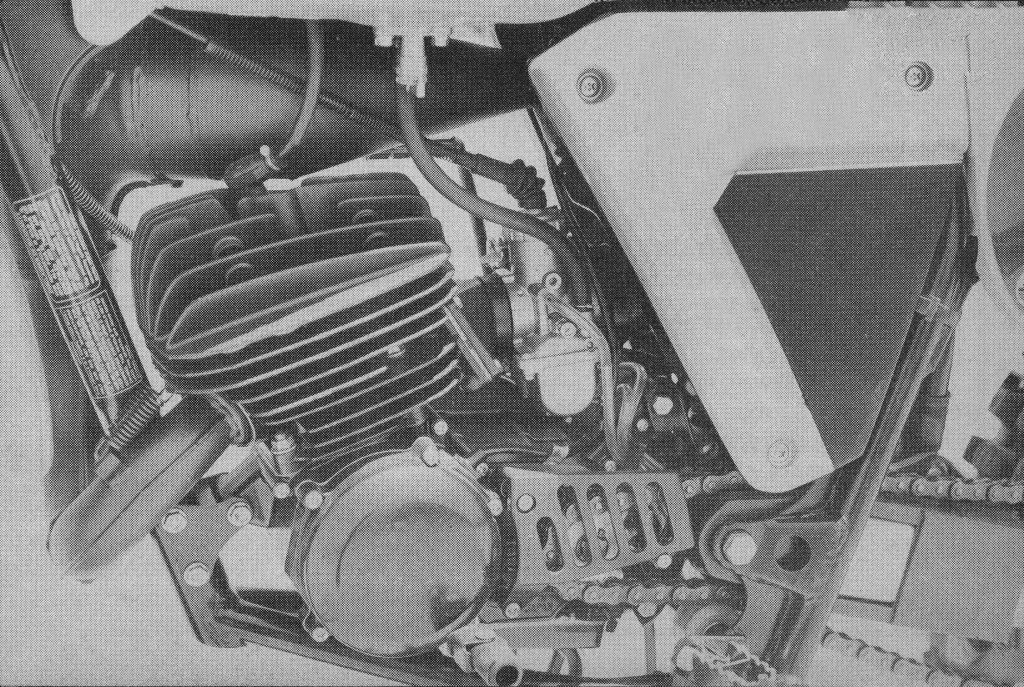

An all-new cylinder for 1980 featured porting cribbed from the road-race department in an effort to boost top-end power. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

An all-new cylinder for 1980 featured porting cribbed from the road-race department in an effort to boost top-end power. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

After two years of dipping its toes into the 125 class with super-low volume offerings, Kawasaki was finally ready to make a push back into the motocross mainstream with a radically redesigned KX125 for 1980. Headlining the changes for ’80 was the introduction of the most significant suspension innovation since the unveiling of Yamaha’s original monoshock YZ in 1975. Dubbed the “Uni-Trak,” Kawasaki’s new monoshock design was a complete departure from anything else offered on a production machine up to that point. Unlike the Yamaha mono, which laid its shock down horizontally along the frame’s backbone, the new Kawasaki design placed the shock vertically behind the motor and attached it to a bell-crank linkage through a set of strut arms. Interestingly, this first version of the Uni-Trak did not offer the rising rate leverage curve that modern linkage-equipped suspension systems have become famous for. Due to patent issues, this was left off of the original Uni-Trak design, but it still offered several advantages over both the Yamaha Monocross and the traditional dual shock designs of the time.

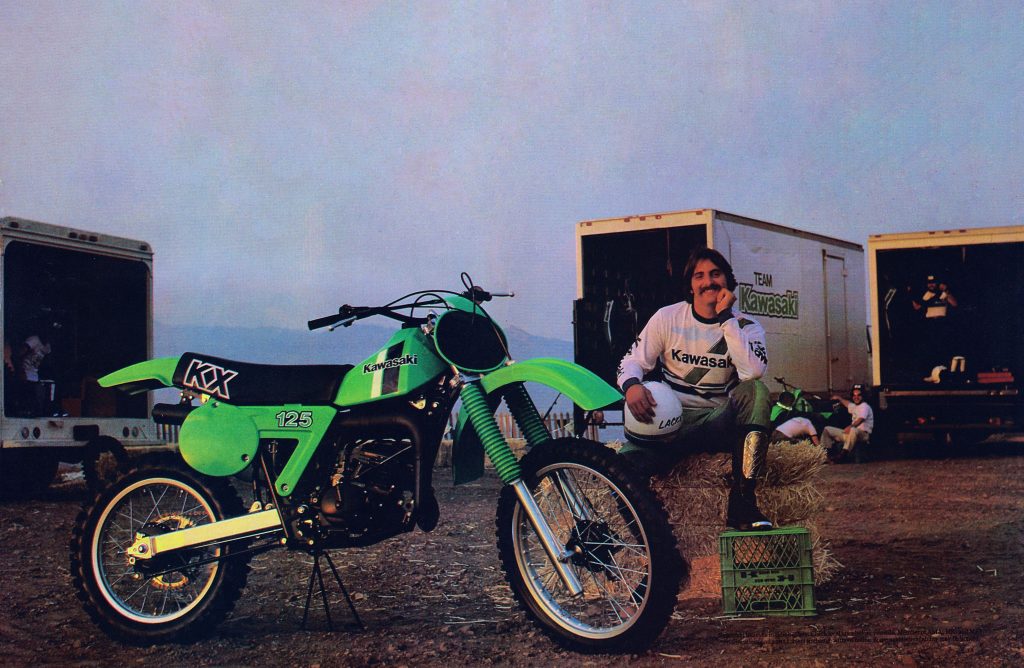

In 1980, Jeff Ward was Kawasaki’s ace in the 125 class. Ward’s SR125 did bear a passing resemblance to the production bike but the stocker did not get the benefit of Wardy’s liquid cooling. Photo Credit: Unknown

In 1980, Jeff Ward was Kawasaki’s ace in the 125 class. Ward’s SR125 did bear a passing resemblance to the production bike but the stocker did not get the benefit of Wardy’s liquid cooling. Photo Credit: Unknown

By moving the shock down and rearward the Uni-Trak offered a much lower center of gravity and a much more compact layout than the Yamaha design. The addition of a linkage and vertical arrangement of the shock also cured many of the odd handling quirks that had plagued the Yamaha monoshock machines from their inception. There was none of the top-heavy feel and weird weight transfer issues found on the YZs. Instead, the new Uni-Trak followed the ground consistently and helped make the bike feel lighter and nimbler than its 201 pounds would have indicated. The Uni-Trak’s shock location also allowed a great deal more cooling air to reach the damper than on the Yamahas and helped alleviate much of the fading that had been a problem on the YZs.

The Uni-Trak’s many levers and pivot points required regular servicing to keep them in proper working order. If neglected, the linkage would develop play and eventually crack the frame at the upper mounting. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The Uni-Trak’s many levers and pivot points required regular servicing to keep them in proper working order. If neglected, the linkage would develop play and eventually crack the frame at the upper mounting. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

When compared to a traditional dual-shock arrangement, the new Uni-Trak also offered several advantages. Ergonomically the move to the single shock allowed Kawasaki to significantly slim the midsection of the KX. The adoption of a single shock also alleviated any issues that might arise from having production variances in two individual shocks. If two shocks were far enough apart in their individual damping, they could actually work against each other and adversely affect the suspension’s performance. By placing the shock vertically, the damper was also put under less stress on hard impacts. This in turn should have resulted in improved reliability and longer-lasting performance.

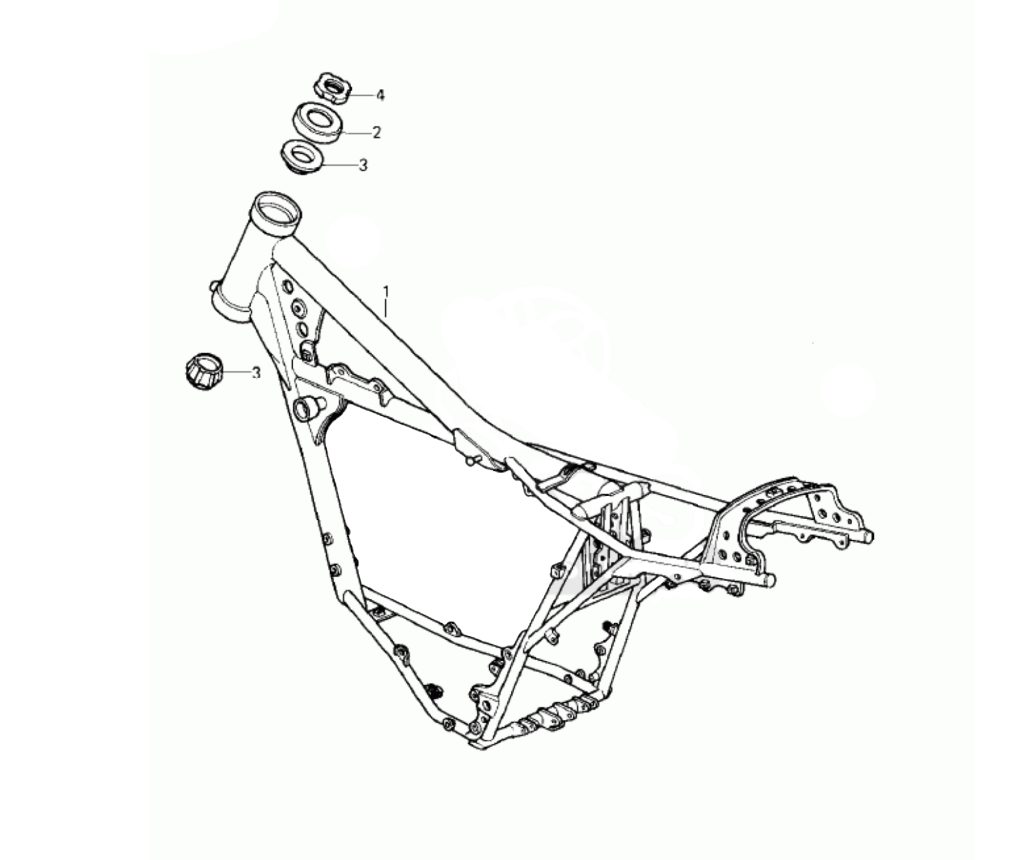

The KX125’s frame was crafted of tough chromoly steel and featured a conventional design aside from the unique mounting points required by the Uni-Trak suspension. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

The KX125’s frame was crafted of tough chromoly steel and featured a conventional design aside from the unique mounting points required by the Uni-Trak suspension. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

As to the rest of the 1980 KX125 package it was a thoroughly conventional design. The chromoly steel chassis featured a large single backbone and a single downtube that spit into a dual cradle below the motor. The motor maintained the air-cooling of 1979 and added new porting designed to boost top-end performance. Internally, the cylinder featured Kawasaki’s exclusive electrofusion coating which was lighter than iron and allowed for better heat transfer. While the coating was very durable, if the motor sucked dirt or suffered a catastrophic failure it could not be bored and required a costly replacement. Being 1980, the cylinder’s design was extremely simple and lacked any sort of variable exhaust valve. This was par for the course at the time and not any sort of disadvantage in relation to its competitors.

On the intake side, the new KX125 featured a 32mm Mikuni round-slide carburetor and a set of class-exclusive Boyesen reeds as standard equipment. While not the popular “dual-stage” reeds that were a common upgrade at the time, the lightweight fiber reeds had helped provide the ’79 KX125 with the snappiest low-end power in the class. Finishing off the motor package for 1980 was an electronic CDI ignition, redesigned expansion chamber, and a close-ratio six-speed transmission.

The new 124cc mill turned out to be the most disappointing part of the 1980 KX125 package. Over-ported and under-carbureted, it produced a listless delivery that failed to impress even novice pilots. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The new 124cc mill turned out to be the most disappointing part of the 1980 KX125 package. Over-ported and under-carbureted, it produced a listless delivery that failed to impress even novice pilots. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Up front, the 1980 KX125 used a set of 38mm Kayaba forks to deliver 11 inches of travel. This was the least movement in the class and nearly an inch less than what was offered on the CR and YZ. While offering somewhat less travel, their 38mm stanchions were beefier than the 37mm units found on the Honda and considered quite stout for the time. External adjustability was limited to air pressure through a pair of Schrader valves at the top of each fork. By varying air pressure, oil height, and viscosity, the fork’s performance could be dialed in to a wide range of riders.

While it was slower than most 100s, at least the 1980 KX125 was a handsome machine. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While it was slower than most 100s, at least the 1980 KX125 was a handsome machine. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Complementing the mechanical changes for 1980 was all-new bodywork that gave the KX an updated appearance. Both the front and rear fenders were restyled and the tank offered a new profile that not everyone was a fan of. The new seat was also firmer for 1980 and contributed to a flatter riding compartment. With its hidden single shock and long alloy swingarm some people thought the new KX was a bit odd looking at the time but most people felt the redesigned bodywork was handsome overall.

Suzuki’s Mark Barnett (10) had Jeff Ward (19) and the rest of the 125 class covered in 1980. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

Suzuki’s Mark Barnett (10) had Jeff Ward (19) and the rest of the 125 class covered in 1980. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

On the track, the all-new KX turned out to be an impressive performer in every category but one. Riders raved about the KX’s handling and suspension but wondered what happed to the ’79 bike’s excellent power. In stock condition, the 1980 version produced a slow-revving and unimpressive flow of power. It was mild down low, sleepy in the middle, and lethargic on top. On the dyno it gave up two horsepower to the CR125 and in the real world of ruts and roost it felt like even more. The motor had to be constantly pinned to the stops to have any shot at keeping up with its rivals. Thankfully, the clutch and transmission worked well and aided in keeping the narrow powerband percolating. If the rider was skilled and the track was hard, the KX could turn competitive laps, but if you added in a little deep soil and some hills then the KX was in serious trouble.

Excellent 38mm Kayaba front forks graced the front of the KX125-A6 in 1980. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Excellent 38mm Kayaba front forks graced the front of the KX125-A6 in 1980. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

After the punchy and very competitive power the ’79 KX125 produced, this step back in performance was quite a surprise to most. Dirt Bike magazine was so puzzled that they went looking for the culprit and discovered several possible answers. After tearing down their test machine and doing some research with several tuners they concluded that the porting changes for 1980 that were aimed at boosting top end power had been too aggressive. They also surmised that the single-stage Boyesen reeds Kawasaki used were too thin and prone to fluttering at high speed. Some tuners also felt the 32mm Mikuni carburetor was too small and the bike would have performed much better with a 34mm or larger mixer. Aware of these power concerns, Kawasaki went so far as to issue an updated expansion chamber mid-year that was designed to reclaim some of the lost performance. While an improvement, this new pipe was not nearly enough to offset the motor’s deeper structural deficiencies.

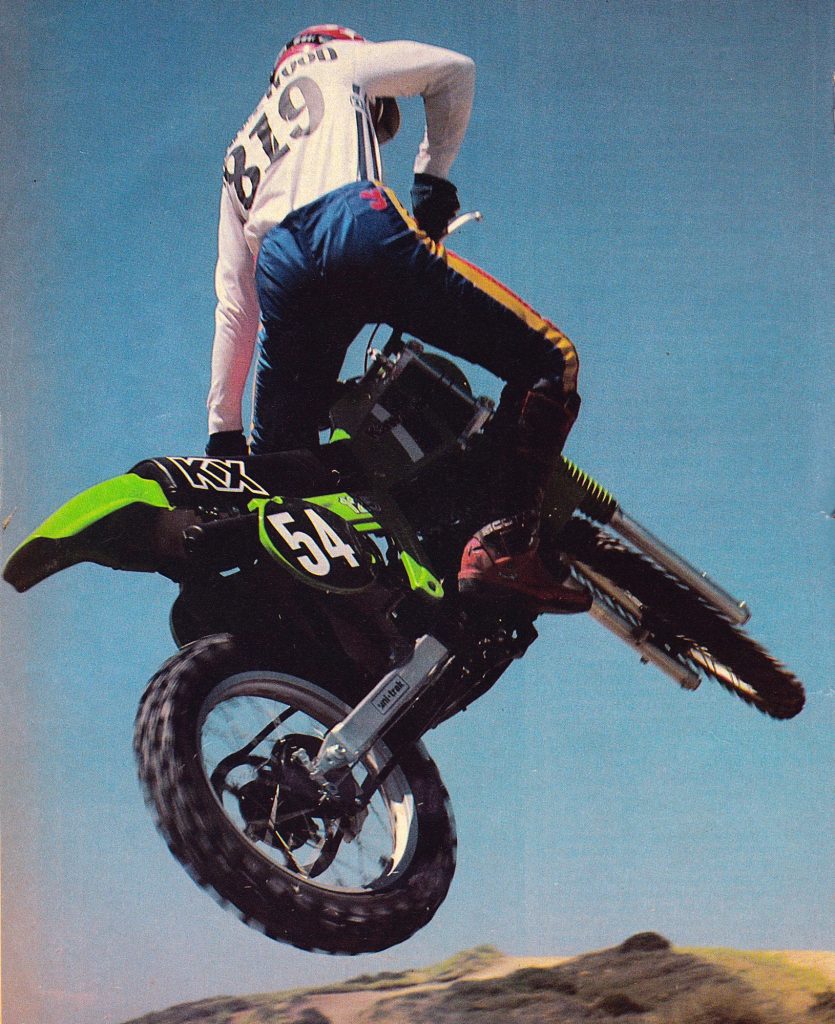

While down on power, most riders found the handling and aerial manners of the KX excellent in 1980. Here Wrecking Crew member Lance Moorewood gets loose on MXA’s test bike. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While down on power, most riders found the handling and aerial manners of the KX excellent in 1980. Here Wrecking Crew member Lance Moorewood gets loose on MXA’s test bike. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1980, the hot setup turned out be the new pipe, a thinner base gasket, a shaved head, a larger carb, and a set of dual-stage reeds. By firming up the reeds, lowering the cylinder, bumping up the compression, and giving the motor more fuel, the power perked up considerably. Even after all of these modifications the KX was still the slowest bike in the class, but at least it was no longer going to get blown off the track by your little brother’s YZ80.

Today, beefy alloy swingarms are commonplace, but in 1980, the KX’s large aluminum lever struck many as overkill. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Today, beefy alloy swingarms are commonplace, but in 1980, the KX’s large aluminum lever struck many as overkill. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

As to the rest of the 1980 KX125 package, it was an unqualified success. Nearly every rider raved about the smooth action of the new Uni-Trak suspension. It offered 11 inches of travel with adjustments available for spring preload and rebound damping. While this was appreciated, the fact that the shock had to be removed to actually make these adjustments was not. This was in direct contrast to the Yamaha Monocross, which made these settings accessible without removing any bodywork. While a pain to adjust, the Uni-Trak’s performance was excellent, offering a plush and well-controlled ride. The new rear end did a great job of putting every one of the KX’s modest ponies right to the track and riders raved about its ability to follow the terrain.

Hills and deep sand were the KX’s worst enemies in 1980. Any sort of resistance was enough to drag down its narrow powerband. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Hills and deep sand were the KX’s worst enemies in 1980. Any sort of resistance was enough to drag down its narrow powerband. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Up front, the new KX’s 38mm Kayaba forks offered a similarly plush ride that won over testers in 1980. In spite of offering less travel than its rivals, its action was rated ahead of them by most testers who found its supple action an excellent match to the Uni-Trak rear. Bottoming was not a major issue but some fast guys found their action a bit soft overall. For them, raising the oil height slightly and adding a few pounds of pressure in each leg would firm up the action enough to be acceptable. While not as unanimously loved as the shock, the KX125’s front suspension was still rated as one of the best available in 1980.

By far the biggest advantage the KX had over its competition in 1980 was the action of its rear suspension system. Smooth and well-controlled, the Uni-Track pointed the way forward for suspension design into the 1980s. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

By far the biggest advantage the KX had over its competition in 1980 was the action of its rear suspension system. Smooth and well-controlled, the Uni-Track pointed the way forward for suspension design into the 1980s. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Like the suspension, the handling on the new KX had a lot of supporters in 1980 but not everyone was enamored with the layout of the new machine. Several riders commented that the foot pegs felt too far forward and virtually no one liked the stock bar bend. Some riders also felt the front end was a bit low and liked the bike much better once the forks were raised slightly in the clamps. Once you raised the forks, ditched the bars, and acclimated to the pegs the KX was capable of turning some fast lap times. With its light weight, mild motor, and excellent suspension the little Kawasaki could be pinned to the stops and ridden with reckless abandon. It tracked great in the rough and stuck like glue in the corners. Flat turns, off-cambers, and ruts were all conquered with ease on the green machine. High-speed runs were not really its forte, but the KX was stable in the rough and confidence inspiring at speed. Overall, the KX125 chassis was rated the best handler of the 1980 125 field.

With able handling and excellent suspension the 1980 KX125 was capable of generating competitive lap times but it took a talented rider like Jimmy Weinert to make the most of its narrow power spread. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With able handling and excellent suspension the 1980 KX125 was capable of generating competitive lap times but it took a talented rider like Jimmy Weinert to make the most of its narrow power spread. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the detailing front the KX125 was not a real standout in 1980. No one liked the low-boy bars, slightly odd ergonomics, or mushy and underpowered brakes. Thankfully, the bike was slow, so the anemic brakes were not too much of an issue. Overall motor reliability turned out to be good but there were some issues with leaking crank seals and if you sucked dirt into the motor the electrofusion cylinder coating made the repairs more costly than the others. The fact that you had to tinker with the motor and swap several parts to get even moderate performance out of the engine was also a major demerit. The motor mounts were problematic as well and in need of constant attention. After investigating the issue Dirt Bike found that Kawasaki had installed bolts that were too small for the holes. Upgrading these to a larger diameter reduced vibration and prevented them from constantly coming loose. Some of the reasoning behind the smaller diameter bolts may have been an attempt to offset the weight of the Uni-Trak. At 201 pounds the KX was 14 pounds heavier than the YZ125 and the heaviest bike in the class. In addition to adding a significant amount of weight, the new Uni-Trak upped the KX’s maintenance demands significantly. The struts, rocker arms, and shock all had pivot points that needed to be serviced regularly to prevent them from wearing out. If you neglected this maintenance then the Uni-Trak developed play in the linkage that would eventually lead to cracks at its mounting points. More than a few KXs suffered frame breakages from this neglect in 1980.

As a showcase for new suspension technology the 1980 KX125-A6 was a standout, but as a racer, it lacked the motor performance to be a legitimate contender in the cutthroat 125 class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

As a showcase for new suspension technology the 1980 KX125-A6 was a standout, but as a racer, it lacked the motor performance to be a legitimate contender in the cutthroat 125 class. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Overall, the radically new KX125 A-6 for 1980 turned out to be a leap forward in one area and a leap back in another. Its Uni-Trak rear suspension wowed riders with its ability to gobble the track while its anemic motor puzzled and frustrated with its inability to back up its suspension prowess. Bold, innovative, and groundbreaking, the 1980 KX125 was a beautiful design exercise fatally handicapped by a lack of horsepower.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com