For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to look back at one of the more controversial machines of the 1990s, Suzuki’s 1997 RM250.

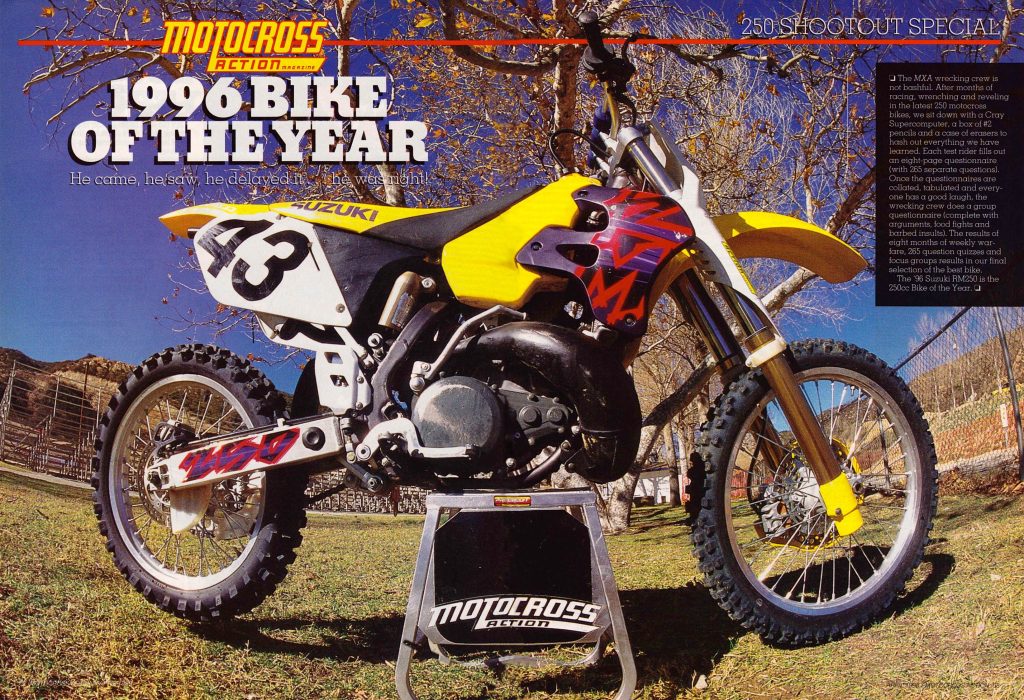

Aside from a slight change in graphics, the 1997 RM250 looked nearly identical to its shootout-winning predecessor. While visually similar, the two machines turned out to perform very differently on the track. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Aside from a slight change in graphics, the 1997 RM250 looked nearly identical to its shootout-winning predecessor. While visually similar, the two machines turned out to perform very differently on the track. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Today, the 1997 Suzuki RM250 is largely remembered as a disappointment by the moto masses. Mostly due to high-profile drama at the professional level, the ‘97 RM250’s reputation has been permanently tainted by the perception of failure. In reality, however, the 1997 RM250 was far from the roach of a machine many today would have you believe. It was a bike with many virtues and one fatal flaw that ended up taking the fall for a poorly planned season that ended in disappointment. Fairly or unfairly, the 1997 RM250 with forever be remembered as the machine that broke Jeremy McGrath’s incredible streak of Supercross dominance. While that had very little to do with the machine’s competitiveness below the AMA professional level, this perceived failure has forever colored the public’s perception of the 1997 RM250.

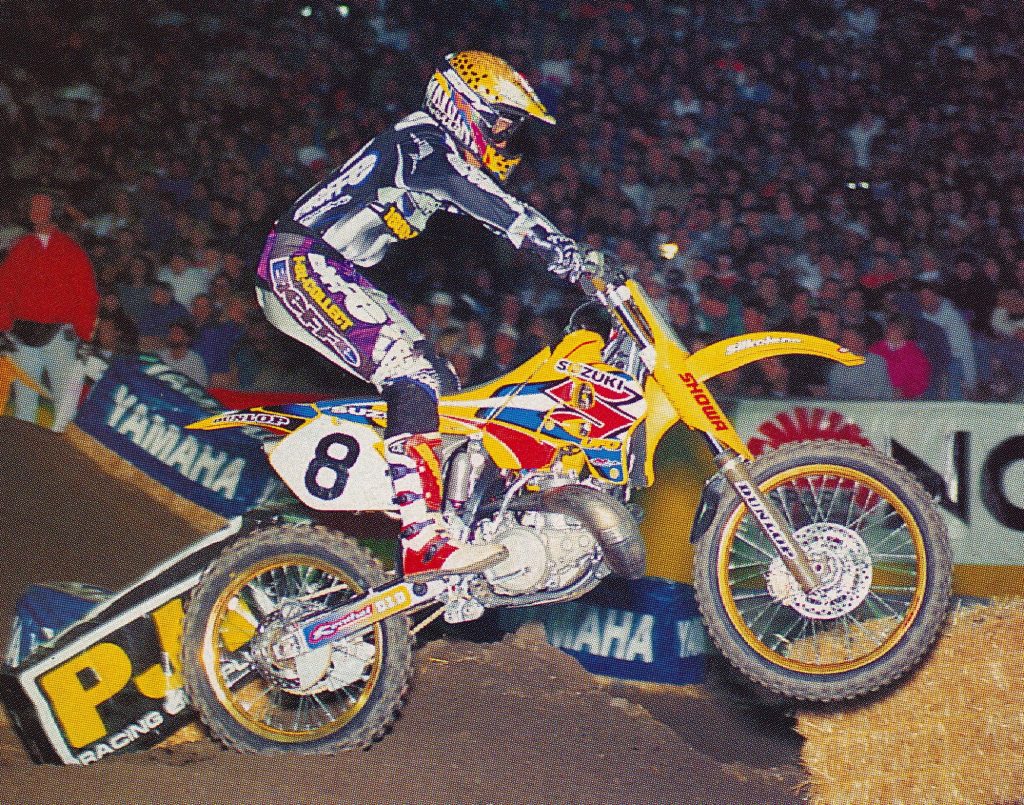

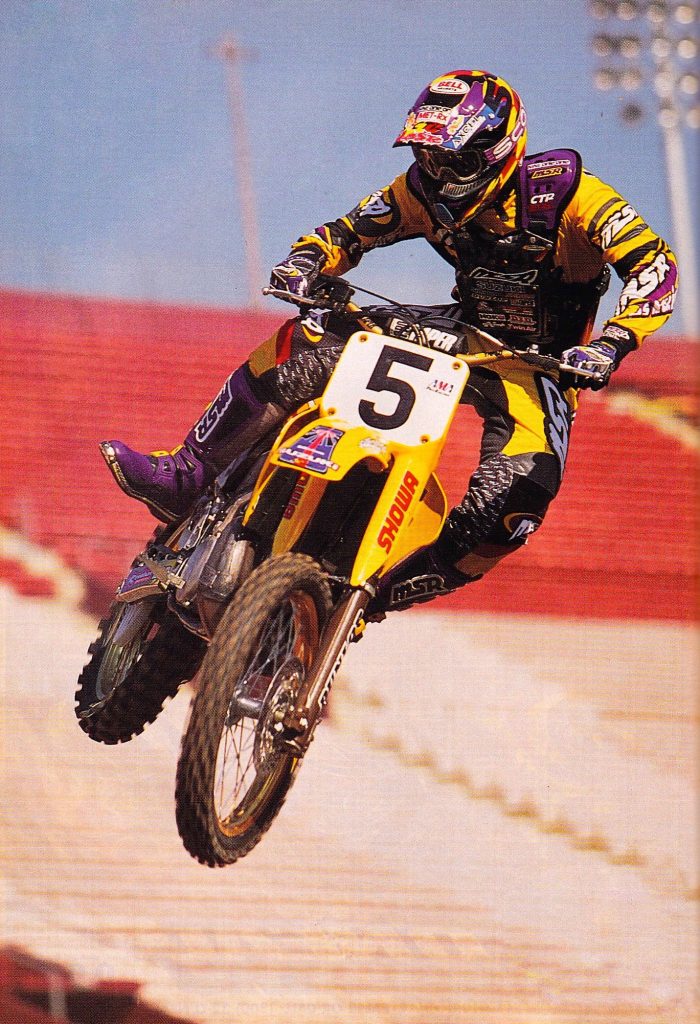

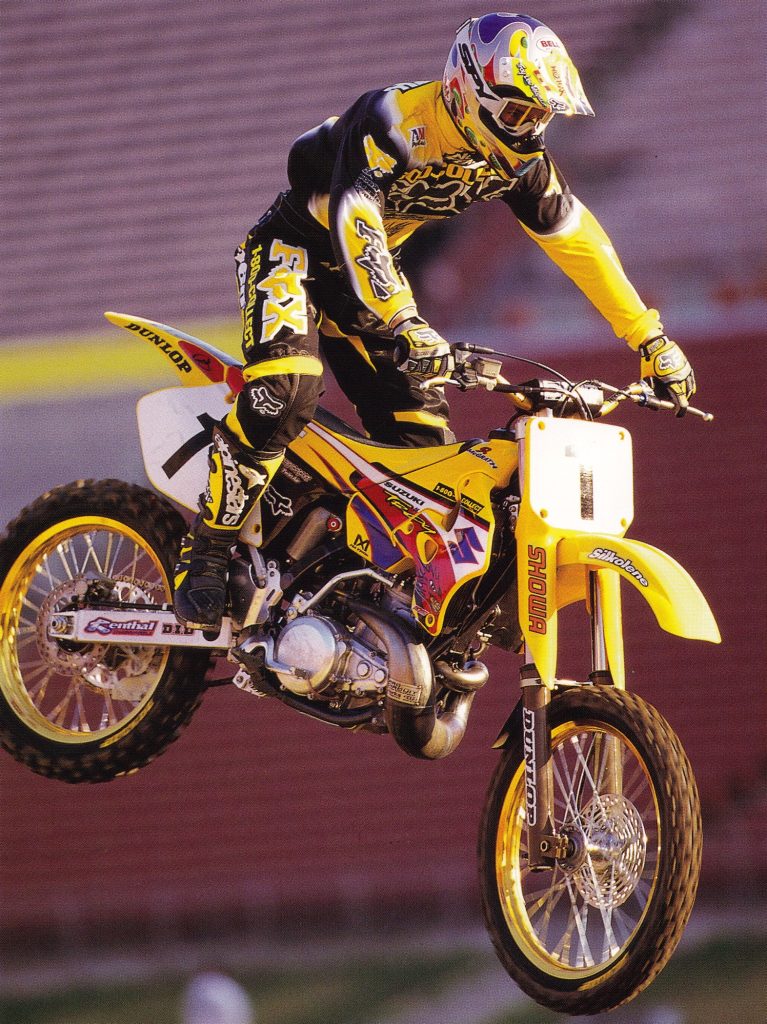

Today, most of the 1997 RM250’s bad press can be traced back to Jeremy McGrath’s last-minute switch to the yellow team. After an eleventh-hour falling out with the Honda squad, McGrath teamed up with Phil Alderton and Roger De Coster to campaign the 1997 Supercross season. A lack of prep, unfamiliarity with the machine, and internal drama within the team all contributed to a lackluster season that tarnished the reputation of the brand. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

Today, most of the 1997 RM250’s bad press can be traced back to Jeremy McGrath’s last-minute switch to the yellow team. After an eleventh-hour falling out with the Honda squad, McGrath teamed up with Phil Alderton and Roger De Coster to campaign the 1997 Supercross season. A lack of prep, unfamiliarity with the machine, and internal drama within the team all contributed to a lackluster season that tarnished the reputation of the brand. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

For Suzuki, the early nineties were a tough era in the 250 class. After garnering accolades in 1988 with a much-improved RM250, the yellow team had taken a big gamble by introducing an all-new machine in 1989. The redesigned RM made major strides in appearance, ergonomics, and overall design, but met with rather mixed reviews in the magazines. Its new case-reed motor was long on punch but short on the breadth and its ultra-aggressive new chassis was great for Supercross but sketchy at anything else. Riders loved the RM’s looks, turning, and feathery feel, but were more lukewarm on its power characteristics and utter lack of stability. Abrupt, twitchy, and at times unpredictable, the RM250s of the early nineties were Supercross bred machines that put off as many riders as they pleased.

While history has been largely unkind to this generation of RMs, they were far from thought of as failures at the time. In 1996, the all-new RM250 was ranked by several magazines as the best overall machine available in the 250 class. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While history has been largely unkind to this generation of RMs, they were far from thought of as failures at the time. In 1996, the all-new RM250 was ranked by several magazines as the best overall machine available in the 250 class. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

By 1995, Suzuki was ready to finally scrap their aging 250 platform in favor of an all-new design. That season they lured five-time World Motocross champion Roger De Coster out of retirement to help right their ship and he was very keen to get their team an improved machine for 1996. Originally, this new platform was slated to make its debut in 1997, but De Coster pushed the brass in Japan to move that timetable forward. While it would be a late-season release, Suzuki agreed to fast-track the new RM and get it to the race team and in the hands of consumers ahead of schedule.

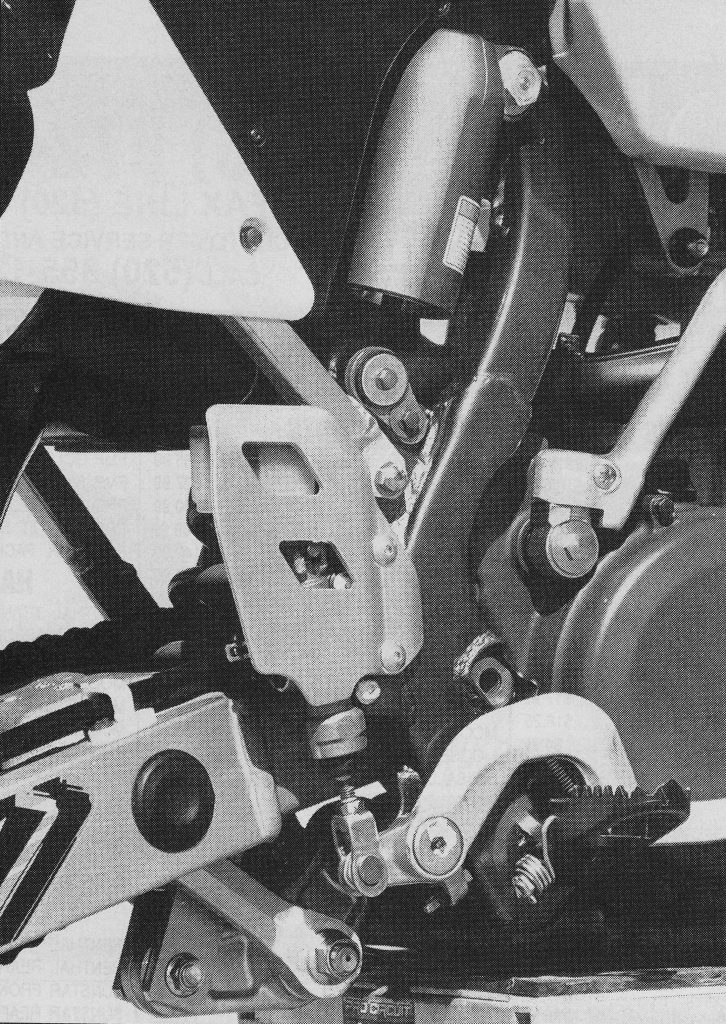

An all-new shock and “works style” linkage highlighted some of the most significant changes on the RM250 for 1997. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

An all-new shock and “works style” linkage highlighted some of the most significant changes on the RM250 for 1997. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

Unlike the 1993 refresh, this new machine was set to be a complete reimagining of the RM250 platform. At the time, many considered Honda’s CR250R to be the gold standard in the 250 class and the new Suzuki design was set to crib more than a few design cues from the highly successful red machines. A new motor did away with the old RM’s controversial case-reed intake and replaced it with a more conventional (for a 250) direct cylinder induction. The chassis was all-new as well and aimed at taming much of the old machine’s unruly behavior. On the suspension front, the new RM250 broke new ground by eschewing the conventional wisdom of the time and introducing an all-new 49mm conventional fork that aimed to combine the precision of the inverted designs with the compliance of the old-school conventional forks of the eighties. This “New Conventional” design combated flex by increasing the diameter of the legs significantly and reducing the underhang below the axle to address the other major complaints riders had voiced about the older designs. Internally, the forks were less of a departure, retaining Showa’s excellent twin-chamber cartridge design for their damping control.

An upside-down world: Today, Suzuki’s switch back to conventional forks in the mid-nineties is largely thought of as a misstep, but at the time it provided a significant advantage in performance. Their excellent combination of comfort, compliance, and control garnered rave reviews from consumers and magazine editors alike. Eventually, discontent with their performance at the professional level and a lack of adoption by the other manufacturers would lead Showa and Suzuki to discontinue their development. Photo Credit: Suzuki

An upside-down world: Today, Suzuki’s switch back to conventional forks in the mid-nineties is largely thought of as a misstep, but at the time it provided a significant advantage in performance. Their excellent combination of comfort, compliance, and control garnered rave reviews from consumers and magazine editors alike. Eventually, discontent with their performance at the professional level and a lack of adoption by the other manufacturers would lead Showa and Suzuki to discontinue their development. Photo Credit: Suzuki

For Suzuki, the move to the new platform was a tremendous success. The new RM was very well-reviewed by the press, taking home victories in both Motocross Action and Dirt Bike magazine’s 250 shootouts. Riders loved the performance of the new Showa conventional forks, and they were praised for their incredible comfort and compliance. With sleek bodywork, great ergonomics, and a stout chassis, the new RM’s handling was a tremendous improvement over 1995. The machine was a dream on the track with sharp turning, a feather-light feel, and surpassingly good stability.

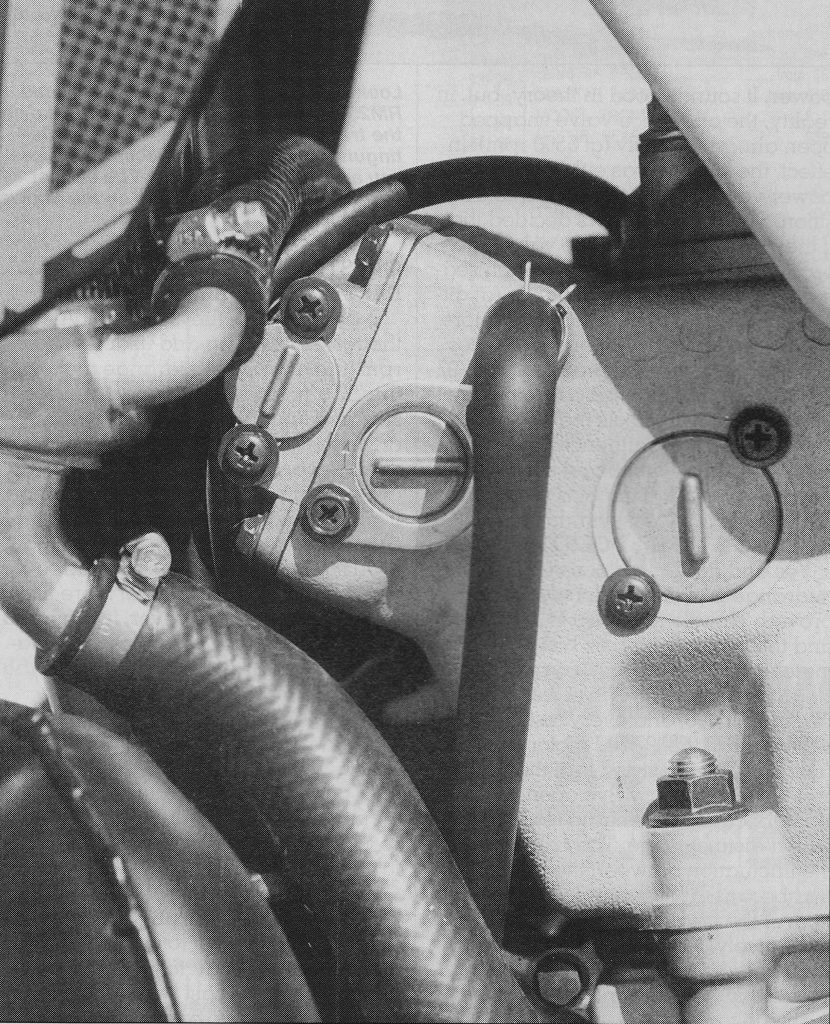

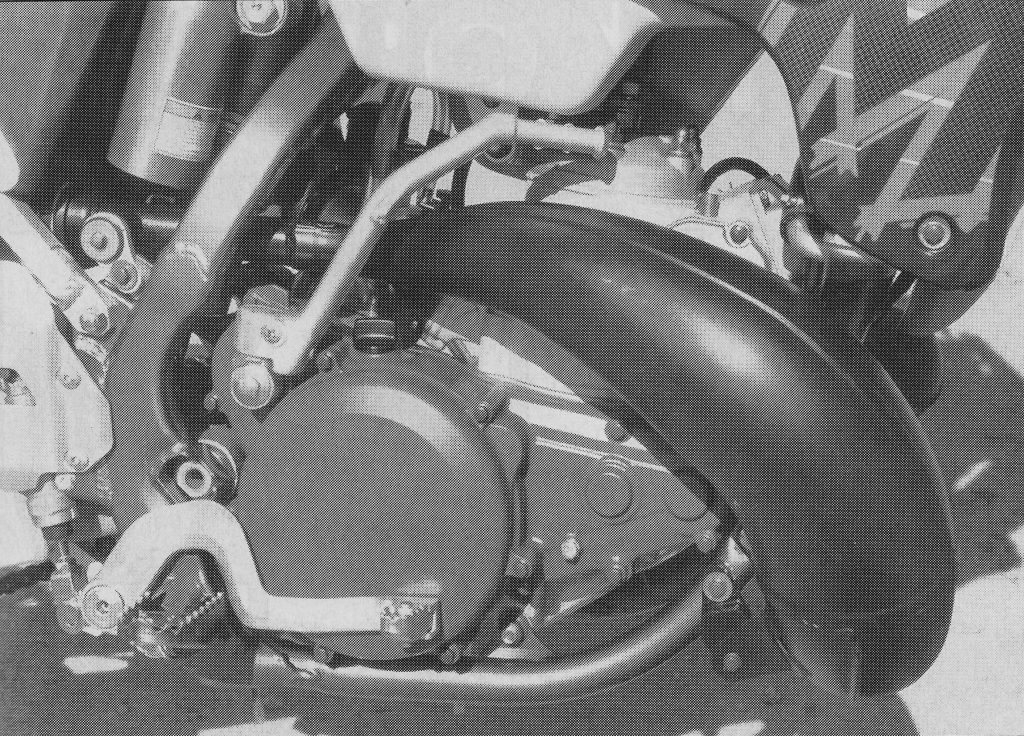

An all-new triple-stage power valve for 1997 looked to broaden the RM’s punchy powerband. Photo credit: Motocross Action

An all-new triple-stage power valve for 1997 looked to broaden the RM’s punchy powerband. Photo credit: Motocross Action

While the new chassis was the star of the show, the RM’s revamped motor was far from a handicap for most riders. The redesigned powerplant mimicked the omnipotent CR250R’s internal dimensions and delivered a reasonable facsimile of the red machine’s performance. Low-end torque and top-end power were much improved with the RM delivering a wide and easy-to-use spread of power. It was still not as powerful as the brawny CR and torque-monster KX, but it easily outpowered the anemic YZ and outgoing RM.

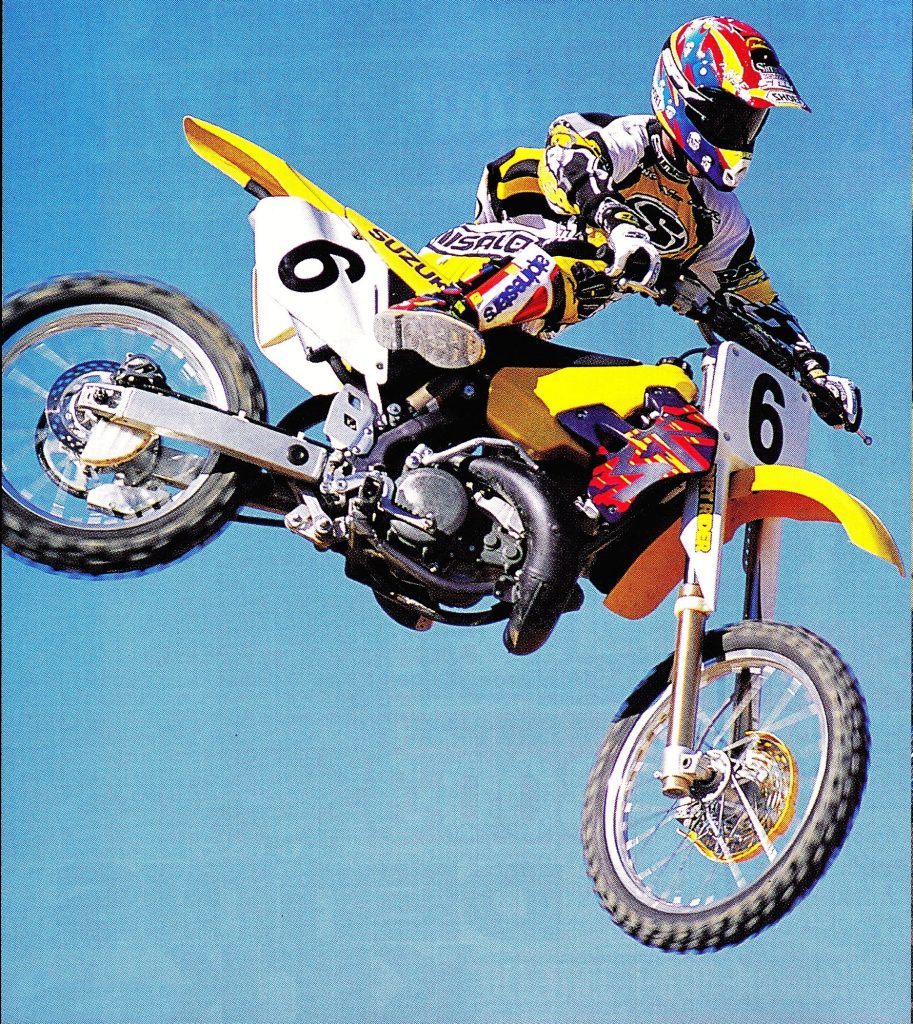

By far the biggest surprise of the 1997 Supercross season was the out-of-nowhere victory by Greg Albertyn at the season opener. After two crash-filled and disappointing seasons in the stadiums, the popular South African rider finally put things together to give Suzuki its first 250 Supercross win since Mike LaRocco in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

By far the biggest surprise of the 1997 Supercross season was the out-of-nowhere victory by Greg Albertyn at the season opener. After two crash-filled and disappointing seasons in the stadiums, the popular South African rider finally put things together to give Suzuki its first 250 Supercross win since Mike LaRocco in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Where things went wrong for the RM was in the quality department. The production rush led to many failures that probably could have been avoided with a little more time and testing. Kickstarters, transmissions, clutches, linkages, and wheels all proved fragile and prone to failure. Some of these issues were handled by dealers and some of them were left to the consumer to grin and bear. If you were slow and easy on your machine, you were likely to love your new RM. If, however, you were a pro-level hammerhead, you were likely to rack up quite an extensive repair bill keeping the fragile Suzuki on the track.

After stealing the lion’s share of the press in 1996, Suzuki was relegated to yesterday’s news by the debut of Honda’s revolutionary all-new alloy framed CR250R in 1997. In the end, neither machine was as successful on the track as Kawasaki’s less flashy but more proven KX250. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

After stealing the lion’s share of the press in 1996, Suzuki was relegated to yesterday’s news by the debut of Honda’s revolutionary all-new alloy framed CR250R in 1997. In the end, neither machine was as successful on the track as Kawasaki’s less flashy but more proven KX250. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

At the factory level, this fragility was less of an issue, but De Coster’s squad endured their own myriad of issues in 1996. While the move to the new conventional forks was lauded by magazine editors and consumers alike, it was less loved by AMA pros like Mike LaRocco and Greg Albertyn who found its built-in compliance a hindrance rather than a blessing. For elite riders like LaRocco and Albee, the new conventional forks displayed too much flex for proper control. For them, the new motor was also far too mellow, and its all-new design meant that Suzuki was behind its rivals in developing high-performance parts to extract the desired performance. Unfortunately, this internal discontent within the factory team made its way to several moto media outlets and this only served to further tarnish the reputation of Suzuki’s all-new machine.

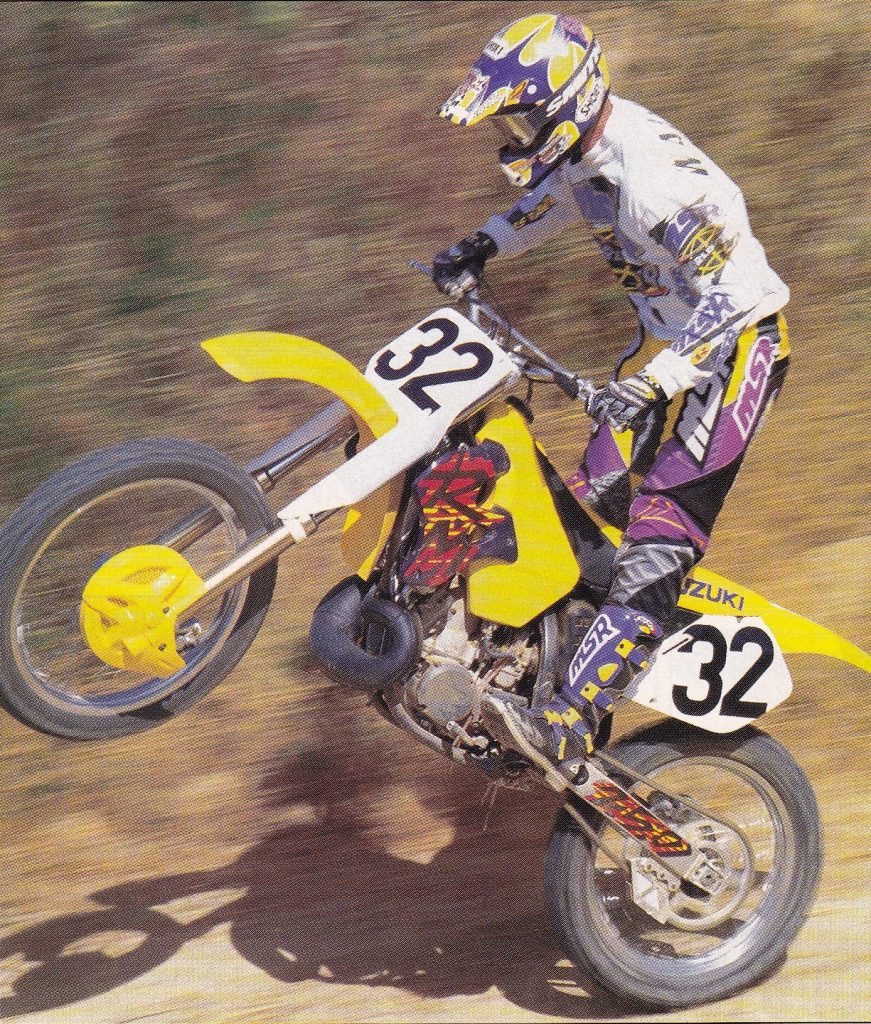

Few pairings in the sport have been as volatile as Mike LaRocco’s two-year stint with Factory Suzuki in the mid-nineties. Unhappiness with the bike, accusations of favoritism, and internal clashes between Mike’s family and Suzuki management led to Mike leaving the team at the end of the 1997 season. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

Few pairings in the sport have been as volatile as Mike LaRocco’s two-year stint with Factory Suzuki in the mid-nineties. Unhappiness with the bike, accusations of favoritism, and internal clashes between Mike’s family and Suzuki management led to Mike leaving the team at the end of the 1997 season. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

For 1997, Suzuki set out to address many of the ’96 model’s shortcomings with a slew of minor to modest updates. First up was a redesigned cylinder that aimed to boost power by redesigning the power valve system. In 1996, the RM new motor featured a single-stage power valve that slid open using a pair of guillotine-style valved placed at the top of the exhaust port. While effective at giving the RM a solid ‘hit” in the midrange, their “on-or-off” action made the transition into the midrange rather abrupt. In 1997, Suzuki modified the AETC (Automatic Exhaust Timing Control) system to allow the valve to open in stages. This was done by dividing the guillotine valves into two separate sections. At low rpm, the valve remained closed, but now as the RPM rose, the valves opened gradually in two steps. In theory, this staging would provide a smoother transition as the AETC engaged.

The RM’s innovative “New Conventional Twin Chamber Cartridge Forks” used massive 49mm stanchions to combat flex while still providing an ultra compliant ride. They worked excellently for outdoor motocross but even with an additional brace, top-tier pros found them too flexy for stadium use. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The RM’s innovative “New Conventional Twin Chamber Cartridge Forks” used massive 49mm stanchions to combat flex while still providing an ultra compliant ride. They worked excellently for outdoor motocross but even with an additional brace, top-tier pros found them too flexy for stadium use. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Mated to the revised power valve was an all-new cylinder with revised porting to further broaden the power. A new ignition was added that Suzuki claimed would provide a more even burn by delivering a series of small sparks instead of a large single one. For 1997, the RM adopted the KX250’s 38mm Keihin PWK38 carburetor which featured small “winglets” in its venturi to reduce intake turbulence at low throttle settings. A new exhaust was added that was reshaped to boost low-to-midrange torque.

The motor changes for 1997 ended up narrowing the power of the RM’s 249cc mill. Midrange power was up but that came at the expense of low-end torque. The new “burst” powerband was a throwback to the Suzuki motors of the early nineties and not everyone was enthused about its return. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The motor changes for 1997 ended up narrowing the power of the RM’s 249cc mill. Midrange power was up but that came at the expense of low-end torque. The new “burst” powerband was a throwback to the Suzuki motors of the early nineties and not everyone was enthused about its return. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

To address the durability concerns of 1996, Suzuki beefed several of the components in the RM clutch and transmission. The redesigned clutch featured a switch from aluminum to steel for the drive plates and a softer compound for the friction plates. This was done to increase longevity, reduce fluctuations in play at the lever, and deliver a more positive engagement. In the transmission, both second and fourth gear was increased in strength and the final drive was lowered by adding an additional tooth to the rear sprocket (13/50 vs 13/49 in 1996). As in 1996, the water pump continued to be housed inside the outer cases. This allowed Suzuki to use magnesium for their construction without the corrosion concerns that had plagued Honda in the mid-eighties. This design also reduced the chances of damaging the water pump in a crash. Finally, the rigidity of the crankcase was increased by redesigning the mounting of the sprocket cover to no longer share the same bolt as the center cases.

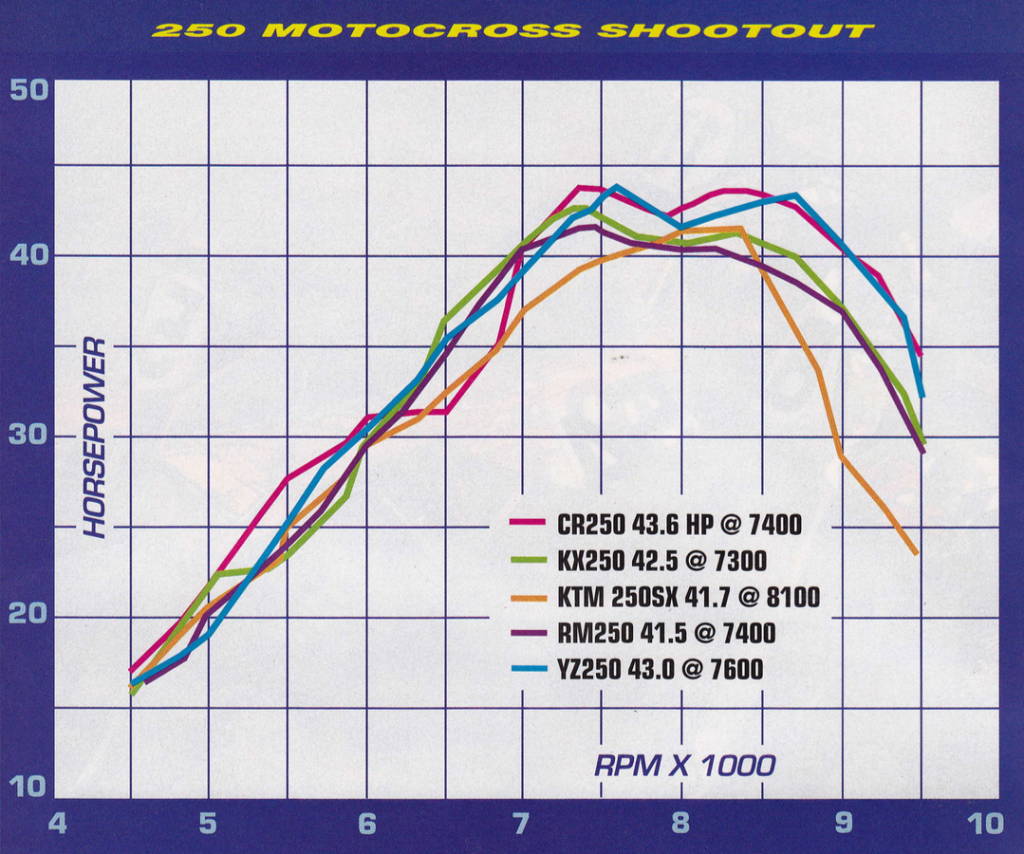

At a peak of 41.6 horsepower the RM250 was the runt of the 1997 power rankings. With its potent midrange, the RM was still competitive in the right hands, but many riders preferred the prodigious grunt of the KX and endless pull of the CR to the Suzuki’s brand of gun and run. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

At a peak of 41.6 horsepower the RM250 was the runt of the 1997 power rankings. With its potent midrange, the RM was still competitive in the right hands, but many riders preferred the prodigious grunt of the KX and endless pull of the CR to the Suzuki’s brand of gun and run. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Despite getting off to a late start Jeremy McGrath’s otherworldly talent almost propelled him to a fifth straight Supercross title in 1997. If not for a flat tire in Charlotte and a calamitously bad fifteenth in the series opener (after multiple run-ins with his former teammate Steve Lamson), McGrath might well have been able to bring Suzuki its first 250 Supercross title since 1981. As it was, two wins and a second place in the final series standings were the best the multi-time champ could muster. Photo Credit: Joe Bonello

Despite getting off to a late start Jeremy McGrath’s otherworldly talent almost propelled him to a fifth straight Supercross title in 1997. If not for a flat tire in Charlotte and a calamitously bad fifteenth in the series opener (after multiple run-ins with his former teammate Steve Lamson), McGrath might well have been able to bring Suzuki its first 250 Supercross title since 1981. As it was, two wins and a second place in the final series standings were the best the multi-time champ could muster. Photo Credit: Joe Bonello

On the chassis front, most of the changes were aimed at the rear suspension. In 1996, the majority of testers had liked the handling of the RM but the shock was less loved. It was stiff in action and prone to kicking at times. In 1997, Suzuki lengthened the swingarm 10mm and redesigned the linkage to mimic the “works” linkages used on their ’96 factory machines. The new linkage was both stronger and designed to be more progressive in its action. The engineers also bolted on an all-new Showa shock that featured a 3mm increase in overall stroke for smoother action.

In 1997, the RM250’s 49mm Showa conventional twin-chamber cartridge forks were the best forks in motocross. Ultra-plush on small chop and silky smooth on big hits, they were unparalleled in comfort and control. As long as stadium whoops were not on your agenda, you could not get a better set of forks than this in 1997. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1997, the RM250’s 49mm Showa conventional twin-chamber cartridge forks were the best forks in motocross. Ultra-plush on small chop and silky smooth on big hits, they were unparalleled in comfort and control. As long as stadium whoops were not on your agenda, you could not get a better set of forks than this in 1997. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Up front, the New Conventional Twin Chamber Cartridge Forks were back with a few changes aimed at refining their performance and further mitigating any anti-conventional concerns. One of the significant concerns about old-school conventional designs was the protrusion of the fork below the axle line. This caused the fork to catch in ruts and potentially affect cornering performance. One of the advantages of the New Conventional design was a significant reduction in this protrusion. In 1997, Suzuki made this even less of a concern by reducing this overhang by an additional 20mm. Internally, the size of the cartridges was also increased to increase plushness and provide smoother action. To further refine the handling of the RM and alleviate wheel reliability concerns, the diameter of the front hub was increased, and the spoke sets were changed from sets of four to sets of six. This both strengthened the wheel and stiffened the front end to increase steering precision. Overall steering geometry was slightly changed for 1997 with the new frame adding half-a-degree less rake. In addition to the revised geometry, the ’97 frame increased chassis strength by enlarging the diameter of the main frame downtube by 3.2mm.

With plenty of snap, a great chassis, and a comfortable feel, the RM was a lot of fun to ride in 1997. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With plenty of snap, a great chassis, and a comfortable feel, the RM was a lot of fun to ride in 1997. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Visually, the new RM looked nearly identical to the ‘96 model, with only a slight change in graphics and a shorter fork being external clues. The bodywork, all-new the year before remained unchanged for 1997, and more than a few people continued to feel the RM looked like a yellow Honda. With the 1997 CR250R moving to a radical new design, this was a less apt comparison, but there was no denying the RM remained a handsome machine.

Adding an aftermarket pipe and silencer helped broaden the RM’s narrow powerband and upgrade its exhaust note but no amount of accessory fiddling ever did away with the odd sounds generated by the RM’s internal water pump. Many people compared the sound to a bunch of ball bearing ratting around inside the motor and felt it made the RM seem prematurely clapped out compared to its competition. Photo Credit: Pro Circuit

Adding an aftermarket pipe and silencer helped broaden the RM’s narrow powerband and upgrade its exhaust note but no amount of accessory fiddling ever did away with the odd sounds generated by the RM’s internal water pump. Many people compared the sound to a bunch of ball bearing ratting around inside the motor and felt it made the RM seem prematurely clapped out compared to its competition. Photo Credit: Pro Circuit

On the track, the 1997 RM250 ran quite a bit differently than the 1996 model that had captured several shootout victories. The new triple-stage power valve gave the powerband a very “stagey” feel that many riders felt was a step back from 1996. Instead of providing a smoother flow of power, the new AETC gave the powerband a segmented feel as the valves slid open. Low-end power was noticeably softer than ’96, with an even stronger hit in the midrange as the valves engaged. Top-end power was improved but the RM did its best work through the middle. With the softer low-end and more abrupt midrange, the RM did feel faster, but it was harder to extract this performance. In many ways, this was a move back to the controversial RM250 powerbands of the early nineties and not everyone was on board with this change. Pros appreciated the hard-hit and increased overrun, but less skilled pilots thought the broader power and smoother transition of the ’96 motor was preferable. Regardless of how you came down on the powerband issue, there was no denying that the RM lacked the firepower of the class-leading Honda and Kawasaki machines. Both the CR and KX outmuscled the Suzuki by a significant margin in 1997. At 41.5 peak horsepower, it gave up over two horsepower to the blazing fast CR250R and offered far less grunt than the ultra torquey KX. In the lower classes, the RM made more than enough power for most riders, but pros were going to need some motor work to keep the CR and KX in sight.

By far the biggest disappointment on the 1997 RM250 was its abysmal rear suspension. The new linkage and shock delivered a busy and punishing ride that ruined the handling of the RM’s otherwise excellent chassis. Photo Credit: Suzuki

By far the biggest disappointment on the 1997 RM250 was its abysmal rear suspension. The new linkage and shock delivered a busy and punishing ride that ruined the handling of the RM’s otherwise excellent chassis. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the suspension front, the ‘97 RM250 was a real tale of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1997. The New Conventional forks continued to garner raves for their ultra-smooth performance. On an outdoor track, they were without peers and riders fast and slow gushed about their incredible ability to soak up obstacles big and small. Overall damping performance was skewed toward faster riders with firm settings that offered excellent control on hard hits while still providing decent comfort on small chop. On hard hits and slap-down landings, the conventional forks were noticeably less harsh than the inverted competition and all three major magazines picked the 47mm Showas as the best forks in motocross. On a Supercross track, ultra-fast pros like Mike Healey noted the increased flex the front-end exhibited but this was only an issue for the one-half of one percent of riders capable of pushing the RM to its limits on such a demanding track. For the vast majority of riders likely to race the RM, the forks were near perfection.

While the RM250s of the mid-nineties are often pilloried for their Supercross prowess, their success as an off-road machine is legendary. Suzuki off-road superstars Rodney Smith, Steve Hatch, and Randy Hawkins took the brand to countless victories during the decade. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the RM250s of the mid-nineties are often pilloried for their Supercross prowess, their success as an off-road machine is legendary. Suzuki off-road superstars Rodney Smith, Steve Hatch, and Randy Hawkins took the brand to countless victories during the decade. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Out back, things were not nearly as successful. The addition of the new shock and “works-replica” linkage took an already mediocre rear suspension system and made it much worse. Under acceleration, the rear of the RM bucked, chattered, and hopped as the shock struggled to keep the rear wheel in contact with the ground. There was way too much compression damping and a harsh spike in the midstroke that no amount of dial spinning seemed to alleviate. Out of slick and choppy turns, the RM was an absolute handful as the hard-hitting motor and hop-o-Matic shock struggled to find traction. Over large whoops and big jumps, the shock worked well, but its performance on smaller obstacles was abysmal. Just as unanimously as the forks had been praised, the ’97 RM’s shock was derided. Both novices and pros hated its performance, and it was rated by far the worst rear suspension in the 1997 field.

Aside from its poor rear suspension the RM was an excellent handler in 1997. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

Aside from its poor rear suspension the RM was an excellent handler in 1997. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

On the chassis front, the RM was an excellent handler once you got the shock sorted. The ultra-plush conventional forks, excellent ergonomics, and aggressive geometry allowed the RM’s pilot to place the machine exactly where they wanted. Front-end traction was excellent, and the RM was capable of cutting under most other machines in the class. With the stock shock in place, however, cornering and overall handling were much less predictable. Exiting turns and at speed, the busy rear shock upset the chassis’ balance making the bike far more of a handful than it should have been. While there was not a lot of headshake, the RM never quite felt planted until you did something to get the stock damper under control. With a revalve and some fine-tuning, the RM was a great handling machine but in stock condition, its poor shock handicapped an otherwise winning design.

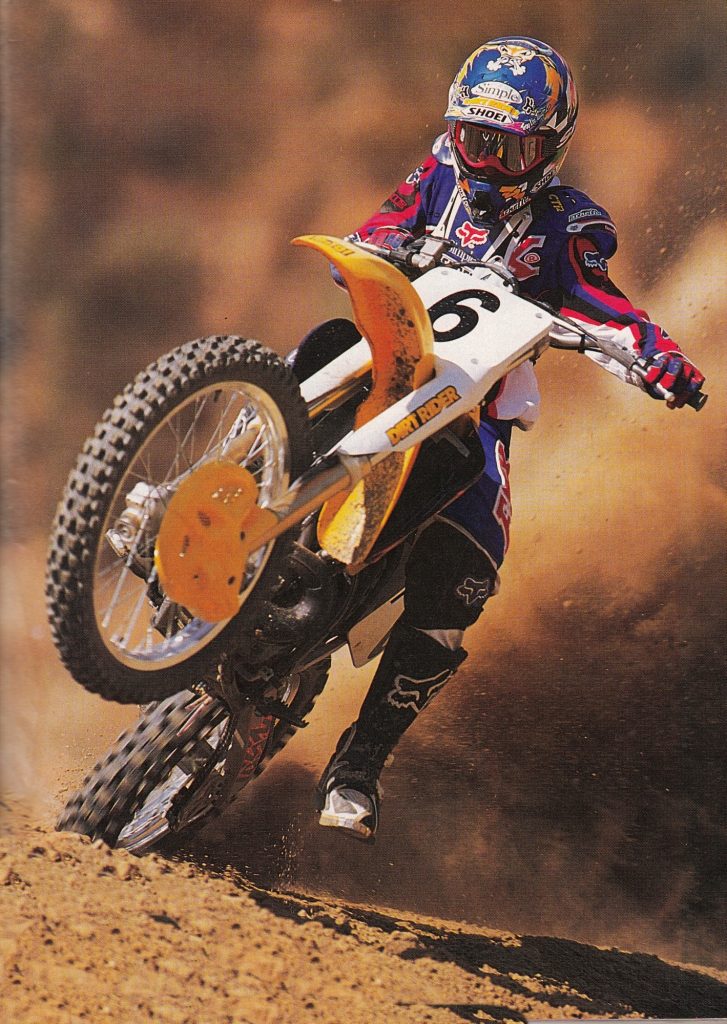

Big air and big whips were big fun on the light and flickable RM. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Big air and big whips were big fun on the light and flickable RM. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the detailing front, the RM was improved for 1997 but still a notch behind some of its competitors. The upgrades to the motor and chassis yielded improved reliability but the RM remained a machine that felt worn out much faster than its red and blue rivals. Excessive play in the levers, butter-soft bars, and an ever-present rattling sound from the motor gave the bike a clapped-out feel that many riders did not appreciate. On the plus side, transmission improvements yielded the slickest shifting cog box in the class and blown gearsets were much less common than the year before. The clutch pull was also super light, but hard-core abusers were likely to need some sort of upgrade to the springs and or plates to prevent fading in long motos. The brakes, ergonomics, and overall comfort of the machine were excellent and nearly everyone commented on how fun the RM was to ride. Its narrow power and wonky shock hindered its effectiveness for racing but if you were looking for a bike to play around on the RM was an excellent choice.

Today, the 1997 RM250 is one of the most misunderstood machines of the decade. Despite two decades of bad press, the machine’s actual performance on the track was not nearly as bad as many would have you believe. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Today, the 1997 RM250 is one of the most misunderstood machines of the decade. Despite two decades of bad press, the machine’s actual performance on the track was not nearly as bad as many would have you believe. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Overall, the 1997 Suzuki RM250 was a machine with many positive traits and one fatal flaw. It offered sano looks, slick ergonomics, a competitive motor, and the best forks in the sport. For the vast majority of the riders not paid to ride the machine, the RM’s next-generation conventional forks were a tremendous advantage. Unfortunately, its poorly setup shock was just as bad as the forks were good and that torpedoed any chance the RM had of repeating its 1996 shootout victories. Despite two decades of bad press aimed at the machine, the 1997 RM250 was not nearly as bad as the conventional wisdom would have you believe. With a shock revalve, the RM was an excellent motocross mount and more than competitive in any class below the AMA pro level. For the 2% of riders capable of pushing the RM to its limits, the motor, clutch, and conventional forks were a hindrance, but that only affected a tiny sliver of the buying public. For most riders, the 1997 RM250 was a fun, fast, and competitive machine capable of winning on any Sunday.