Over the years there have been many unsuccessful attempts by well-respected manufacturers to break into the motocross business. Harley-Davidson, Buell, BMW, and Aprilia have all dabbled in trying to translate street bike success into off-road glory. Today, it is Triumph with an eye towards bringing 120 years of motorcycle heritage to the stadiums of America. On the surface, these moves have all seemed like solid bets. Each of these manufacturers enjoyed loyal followings and a move to off-road racing promised an influx of interest and, hopefully, an increase in sales.

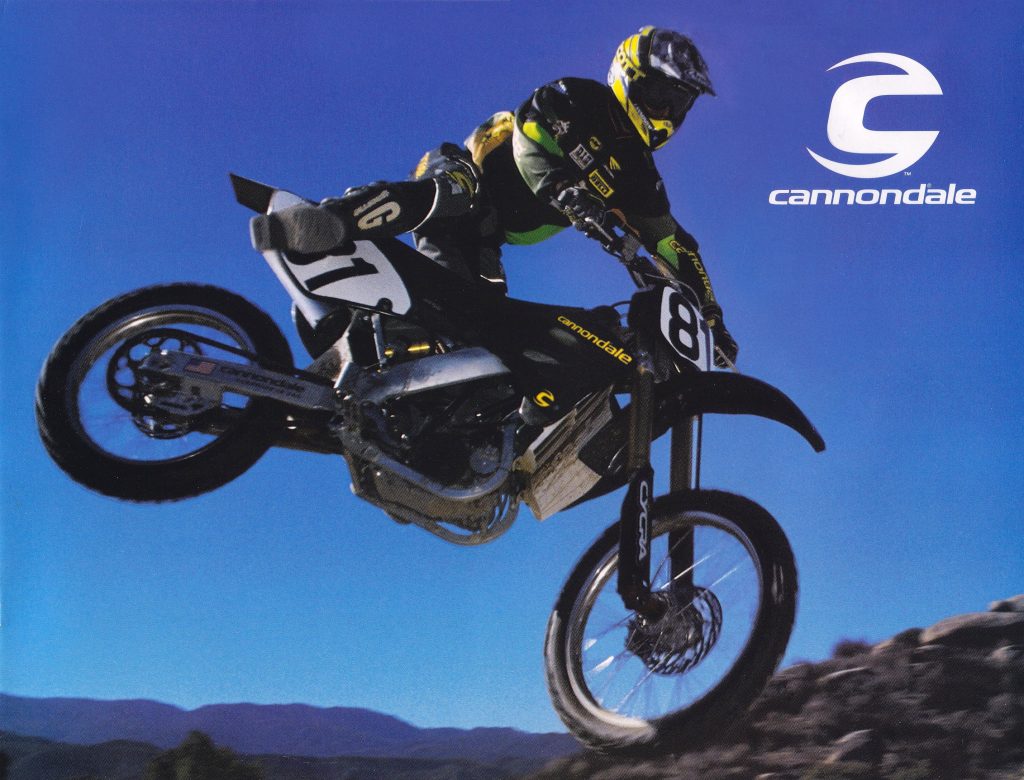

Initially, there was an incredible amount of hype around the new Cannondale motocross machine, but by the time the bike finally made its debut for 2001 the enthusiasm for it had cooled considerably.

Initially, there was an incredible amount of hype around the new Cannondale motocross machine, but by the time the bike finally made its debut for 2001 the enthusiasm for it had cooled considerably.

As history would prove, however, that equation was far from a sure bet. On-road expertise does not guarantee off-road success and many a legendary manufacturer have found the motocross world a difficult one to break into. Motocross is a very specific discipline, and technology and innovation can often be a double-edged sword in off-road racing. Pushing too far and too fast to break new ground can backfire in a sport where reliability and ease of use often win out over absolute performance.

The Cannondale was an incredibly innovative machine that tried to reinvent motocross design in too many ways at once.

The Cannondale was an incredibly innovative machine that tried to reinvent motocross design in too many ways at once.

In the late 1990s, this was just the scenario that played out when mountain bike pioneer Cannondale tried to leverage its aluminum chassis know-how and stellar cycling reputation into a successful motocross operation. At the time, Honda’s all-new aluminum-framed CR250R and Yamaha’s innovative YZ400F four-stroke were the talks of the industry and Cannondale saw an opportunity to capitalize on the hype for both with an all-new machine that combined their best traits into an American-made alternative.

With Cannondale’s excellent reputation in the cycling world many thought the MX400 would deliver America its first legitimate motocross contender.

With Cannondale’s excellent reputation in the cycling world many thought the MX400 would deliver America its first legitimate motocross contender.

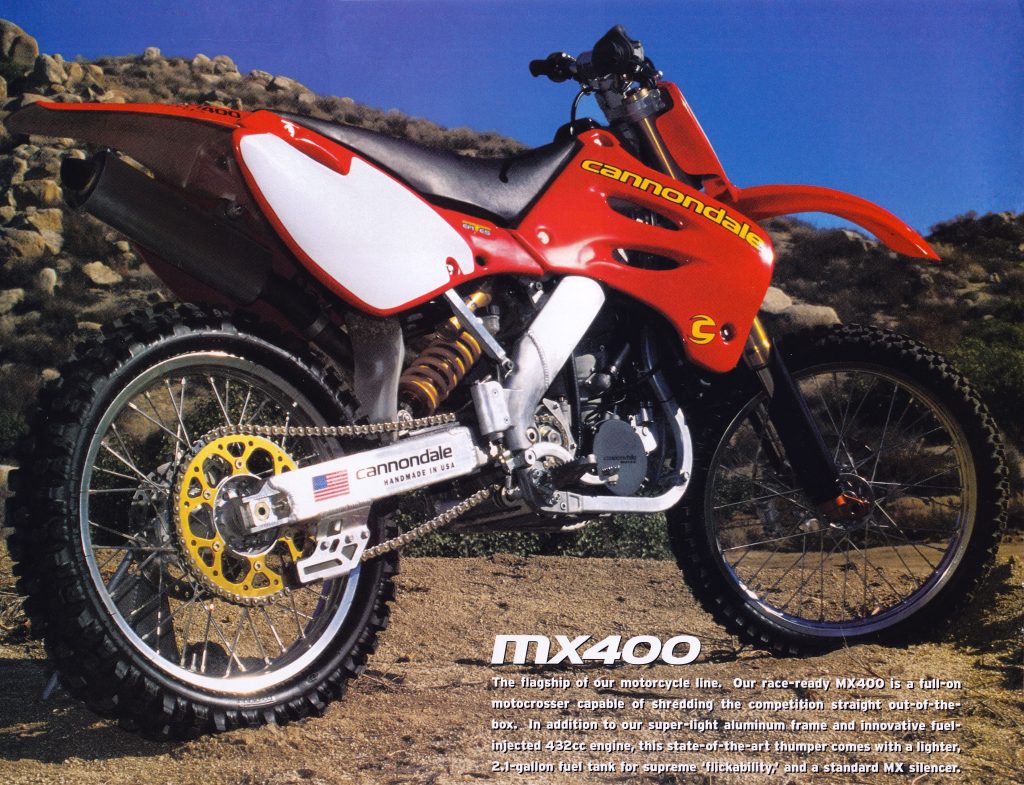

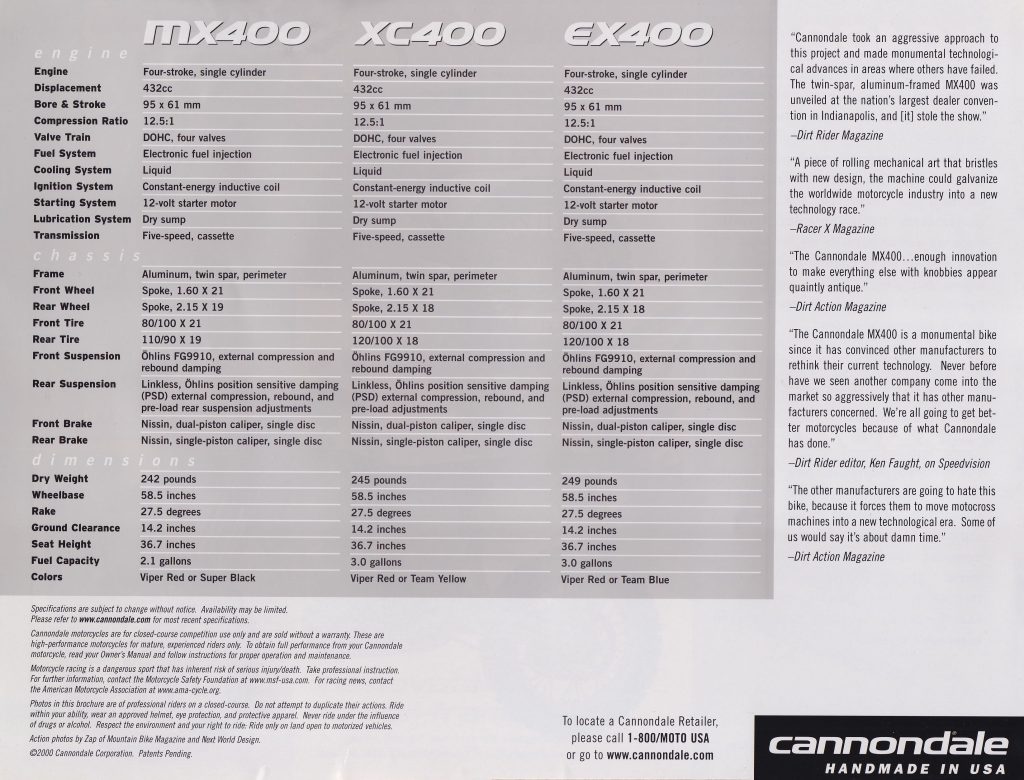

For Cannondale, the promise of a clean sheet design meant that they were free to rethink everything from the chassis to the motor design on their machine. In cycling they had made their reputation with innovation and this ethos to push the envelope forward made its way into every element of the Cannondale motorcycle’s design. The Cannondale engineers decided to reverse the cylinder to allow a straighter intake for improved airflow into the motor and settled on fuel injection for the fuel delivery system. The MX400 featured electric starting as well to alleviate the major complaint riders had with most four-strokes of the time. Today, all these features are seen on Yamaha’s lineup of four-stroke machines, but in the late 1990s, these were very avant-garde ideas.

With fuel injection, electric start, a cassette-style transmission, and reversed cylinder, the MX400’s motor was the most innovative design in motocross in 2001.

With fuel injection, electric start, a cassette-style transmission, and reversed cylinder, the MX400’s motor was the most innovative design in motocross in 2001.

At the time, Cannondale’s ace in the hole was thought to be their proficiency with aluminum chassis construction. Honda’s 1997 CR250R had proven that aluminum could be a viable chassis alternative, but the first generation of their design was far from perfect. Cannondale felt that their years of experience crafting mountain bike frames would give them an advantage in the delicate art of metallurgical design.

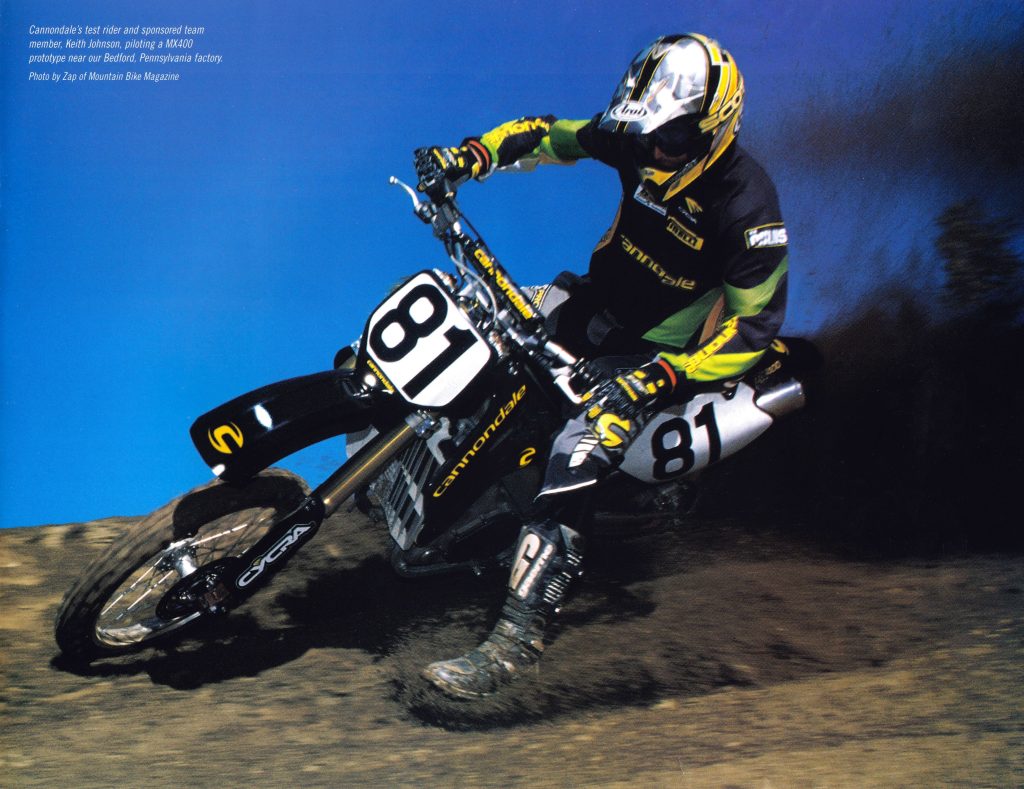

In 2000, Cannondale test rider Keith Johnson raced pre-production versions of the MX400 in the outdoor Nationals. Unfortunately for Keith and Cannondale’s reputation, the bikes proved extremely fragile and unable to finish many of its motos.

In 2000, Cannondale test rider Keith Johnson raced pre-production versions of the MX400 in the outdoor Nationals. Unfortunately for Keith and Cannondale’s reputation, the bikes proved extremely fragile and unable to finish many of its motos.

While Cannondale was quite experienced in frame construction, they were utterly out of their depth in engine design. This led them to contract out the development of the motor for the new machine. Originally, this job went to the Swedish design firm Folan, who crafted a prototype based largely on existing Husaberg designs. Eventually, however, Cannondale moved the development of their motor to a North Carolina-based NASCAR engine builder who executed their vision for an utterly unique reverse-engine design.

The Cannondale’s aluminum chassis featured many interesting features like its air-channel through the steering head, no-link rear suspension, and removable frame rails to aid motor servicing.

The Cannondale’s aluminum chassis featured many interesting features like its air-channel through the steering head, no-link rear suspension, and removable frame rails to aid motor servicing.

For the suspension, Cannondale turned to Swedish manufacturer Öhlins and Cycra was tapped to craft the bodywork. Early targets for the machine had it undercutting Yamaha’s YZ400F by as much as 15 pounds, but by the time the MX400 made it to production three years later its weight had bloated to an XR-like 260 pounds on Dirt Bike magazine’s scale. This placed it 10 pounds north of Yamaha’s already portly YZ426F and 20 pounds more than the KTM 520SX.

With its mellow power, soft suspension, and hefty weight, many people thought the Cannondale’s off-road variants made more sense than its motocross version.

With its mellow power, soft suspension, and hefty weight, many people thought the Cannondale’s off-road variants made more sense than its motocross version.

In addition to the weight, the Cannondale suffered from several issues tied to its innovative design. The air passage built into the steering head of the frame failed to provide enough air flow to the motor and the ultra-short exhaust header necessitated by the reversed cylinder proved difficult to tune. The new fuel injection system also proved problematic and the bike was beset with starting and fueling issues.

Today, people make fun of the Cannondale for its shortcomings, but the press quotes here turned out to be prophetic in some respects. While the MX400 did not rewrite the record books, many of its innovations can be seen on the bikes we ride today.

Today, people make fun of the Cannondale for its shortcomings, but the press quotes here turned out to be prophetic in some respects. While the MX400 did not rewrite the record books, many of its innovations can be seen on the bikes we ride today.

In terms of performance, the MX400 proved to be rather disappointing in most respects. The motor offered a mellow delivery that was pleasant but unremarkable. Flameouts were common and the MX400’s battery was often not up to the task of getting things re-lit once the machine was hot. The premium Öhlins suspension offered tons of promise but was set up far too softly for the machine’s prodigious girth. Reliability was also an issue with early MX400s suffering from a myriad of gremlins that quickly soured the public and press on the unproven machine. It probably did not help that the bike cost $7900 as well, which was $2000 more than a YZ426F would have set you back in 2001.

In hindsight, the original MX400 probably should have been a more conventional design.

Cannondale’s desire to innovate in so many ways all at once put them on a path that was destined to fail. Today, we have seen that many of the design elements found on the original MX400 can work very well in a motocross environment, but it has taken 20 years of development to make that a reality. In many ways, Yamaha’s current YZ450F is an improved vision of what Cannondale was trying to accomplish with the original MX400. While this does not lessen the financial sting of the Cannondale’s failure, it should offer some comfort to the brave and bold engineers who were trying to push forward the state of the art in motocross design back in 2001.