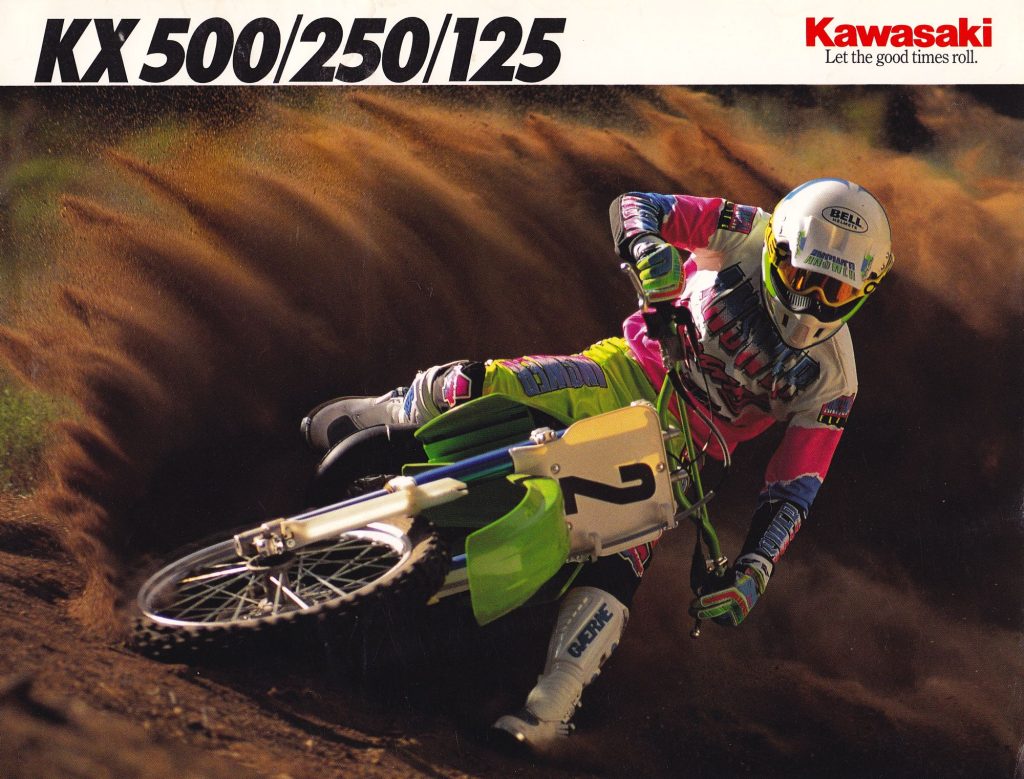

For this edition of Classic Ink, we are going to take a look back at Kawasaki’s 1992 motocross lineup.

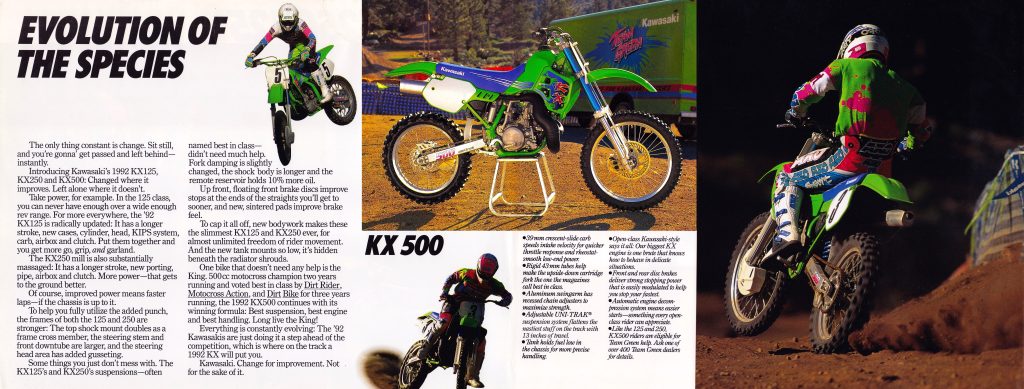

After only two years on the market, Kawasaki revamped their KX125 and KX250 for 1992 with a huge list of updates. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

After only two years on the market, Kawasaki revamped their KX125 and KX250 for 1992 with a huge list of updates. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1990, Kawasaki introduced its first perimeter-framed KX125 and KX250 to much fanfare. The two machines broke major ground in styling and frame design. The new chassis borrowed heavily from the street bike world with its ultra-rigid twin-spar frame design that mimicked the chassis found on many high-performance street machines. Its appearance was just as Avant-guard with bold graphics, bright colors, and spacy bodywork that many credited with kicking off the motocross world’s early nineties fascination with over-the-top styling.

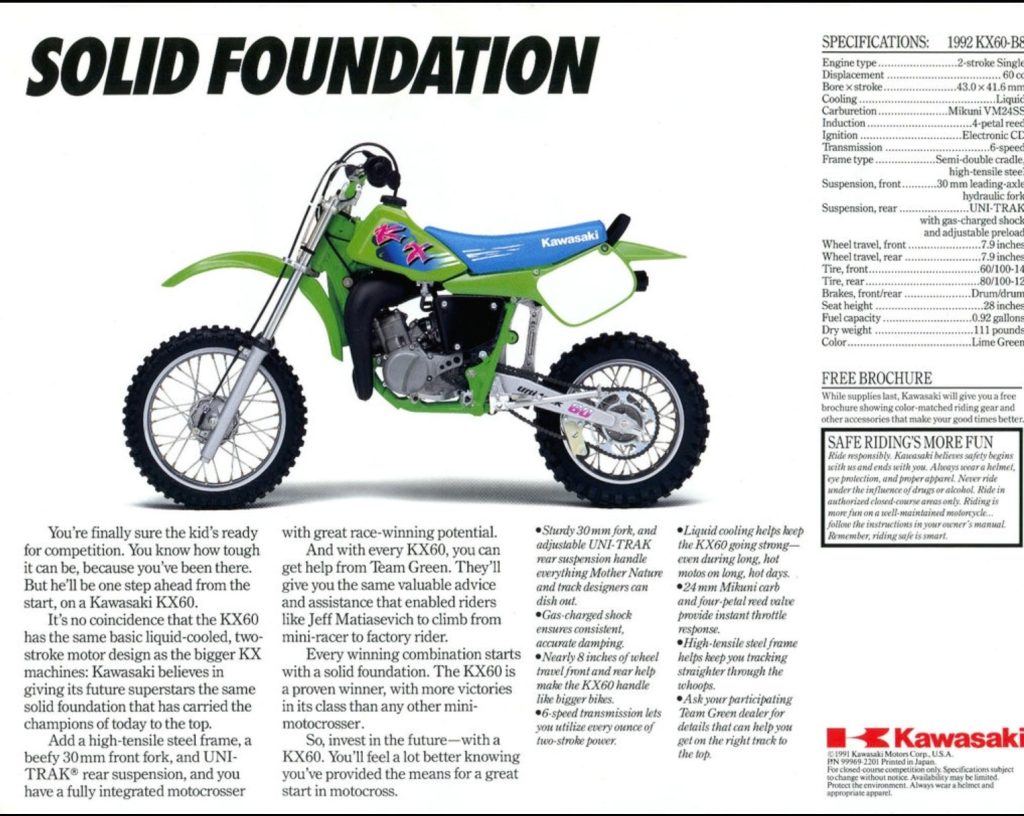

Basically unchanged since 1985, the KX60 remained one of the most successful machines in motocross. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Basically unchanged since 1985, the KX60 remained one of the most successful machines in motocross. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

These new machines proved incredibly popular with riders snapping up the perimeter-framed KXs in droves. While they were a big hit with fans, they were not without their drawbacks. The new chassis was very large and the trick bolt-on alloy shock tower turned out to be a fragile point of failure. Tall riders appreciated the KX’s Paul Bunion feel, but many smaller riders found the trick-looking machines large and unwieldy.

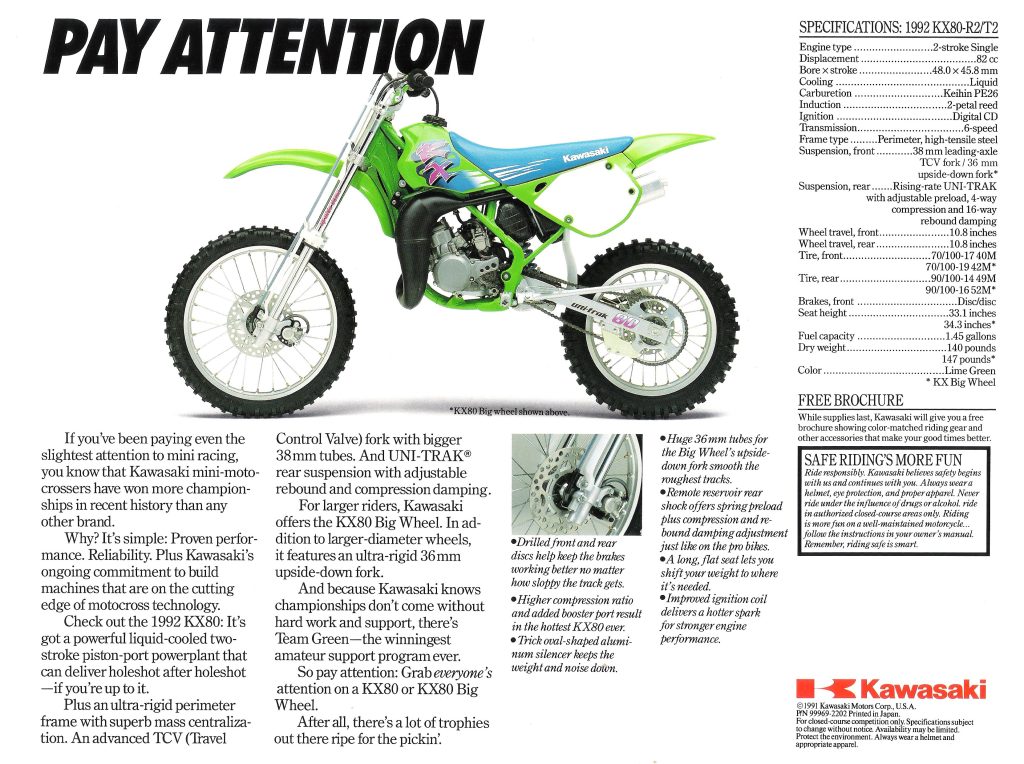

In a class known for slow-moving technology, the KX80 was at the cutting edge of design in 1992. Its stout perimeter frame and trick inverted forks (on the Big Wheel version) allowed skilled riders to push harder and fly higher than many of its competitors. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In a class known for slow-moving technology, the KX80 was at the cutting edge of design in 1992. Its stout perimeter frame and trick inverted forks (on the Big Wheel version) allowed skilled riders to push harder and fly higher than many of its competitors. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1992, Kawasaki retired their first-gen design and introduced another pair of all-new machines. After only two years, the KX125 and KX250 were completely revamped with a huge list of updates and improvements. Today, it would be hard to imagine such a costly update of an incredibly popular machine after only two seasons, but things moved at a much different pace in the eighties and nineties.

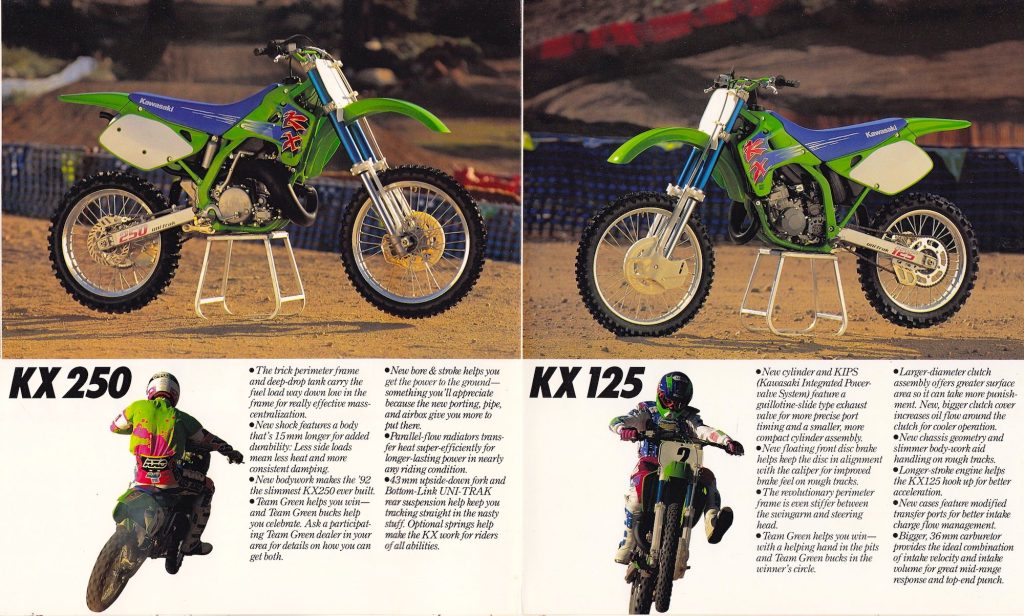

In 1992, Kawasaki made several changes to the KX250’s geometry in search of better stability. These alterations increased stability greatly at the expense of the old machine’s turning accuracy. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1992, Kawasaki made several changes to the KX250’s geometry in search of better stability. These alterations increased stability greatly at the expense of the old machine’s turning accuracy. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Both the 125 and 250 received all-new versions of Kawasaki’s perimeter frame design with several changes aimed at improving ergonomics, fine-tuning the handling, and increasing reliability. The new designs ditched the problematic alloy shock towers and added all-new bodywork that was slimmer and sleeker with graphics that bled from the shrouds right into the seat. All-new brakes moved to a full-floating design in the front that Kawasaki claimed would improve feel by allowing the rotors to “self-center” within the caliper. In the rear, larger 14mm pistons were added to increase power and improve feel. Both machines also received major motor updates that moved to longer-stroke configurations to boost torque and increase rideability. New forks were more rigid for ’92 and all-new shocks featured longer shock bodies with increased volume for reduced fading and more consistent damping performance.

Big changes in 1992 yielded mixed results for the KX125 and KX250. Most riders praised the improved ergonomics and loved the excellent suspension performance the machines enjoyed, but their mellow motors and sluggish turning held them back from topping their respective divisions. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Big changes in 1992 yielded mixed results for the KX125 and KX250. Most riders praised the improved ergonomics and loved the excellent suspension performance the machines enjoyed, but their mellow motors and sluggish turning held them back from topping their respective divisions. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

On the 80cc front, the Kawasaki offered the most up-to-date package in the class. All-new in 1991, the KX80 offered the most advanced chassis in the class and the only “big wheel” offering. Using a scaled-down version of the big bike’s perimeter steel frame, the KX80 offered a chassis capable of pushing the limits of most mini pilot’s skills. For 1992, the KX80 received a new ignition, increased compression, a trick rebuildable alloy silencer, larger forks, and a 20mm larger front disc. For the Big Wheeled version, a new 36mm inverted fork was added to allow big kids to go faster, farther, and harder on the track. Bigger, heavier, and more demanding than many of its competitors, the KX80 offered fast kids a lot of potential, but its lack of a power-valved motor had many preferring Suzuki’s easier-to-ride RM80 in 1992.

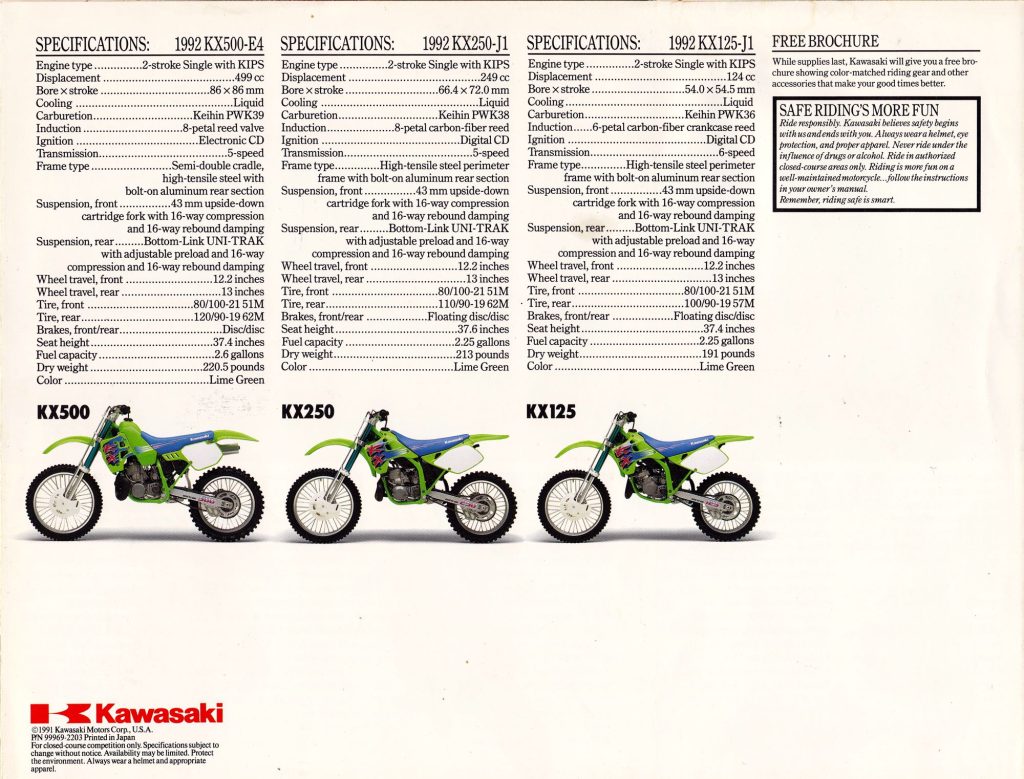

With the KX80, KX125, and KX250 receiving major updates for 1992, it was left to the KX60 and mighty KX500 to soldier on unchanged aside from some graphical changes. As the only Japanese 60 still in production, the KX60 remained stuck in a 1985 time warp. After vanquishing the CR60R, RM60, and YZ60 the KX was left without competition and Kawasaki no longer seemed to feel the need to update their pint-sized rocket. After its move to liquid cooling in 1985, the KX60 remained unchanged aside from Bold New Graphics for nearly two decades. For 1992, Kawasaki kept the status quo for their mighty mini with BNG being its only notable update.

Big, powerful, and cushy, the KX500 was the pussycat of the 500 class in 1992. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Big, powerful, and cushy, the KX500 was the pussycat of the 500 class in 1992. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

All-new in 1988, the 500 was newer, but already starting to look quite old by nineties moto standards. Many had thought the 500 might get the perimeter frame treatment for ’92, but that update never materialized for the green Open class machine. Kawasaki did race several perimeter-framed works versions in the GPs, but by 1992 the writing was on the wall for the traditional 500 class. The AMA was getting ready to phase out the class entirely and in Europe, the big-bore four strokes were starting to take prominence. In the desert the KX500 was king, and many people still loved it for its incredibly wide and tractable powerband, but for motocross, the 500s were no longer the “premier” division in most riders’ minds.

Kawasaki had one of the most well-rounded lineups in motocross in 1992. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

Kawasaki had one of the most well-rounded lineups in motocross in 1992. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

This shift in focus to the smaller displacement classes spelled doom for the KX500’s R&D budget and it would have to make do with only the most modest updates moving forward. For 1992, that meant Bold New Graphics and nothing else. Thankfully, the KX500 was already blessed with the best motor and suspension performance in the class. Its 499cc power plant was the only motor in the class with a power valve and this gave it an unbeatable combination of power and control. It was also blessed with the best suspension in the class, which was even more vital on a machine as heavy and powerful as the KX500. Its ergonomics were still far too pudgy and its brakes were not nearly powerful enough, but if you were looking to go fast in the desert or on the track it was hard to beat Kawasaki’s Jolly Green Giant.