For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to look back at Suzuki’s revolutionary LT250R Quadracer for 1985.

In 1985, Suzuki upended the high-performance ATV hierarchy by releasing the industry’s first fully-suspended two-stroke quad, the LT250R Quadracer. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1985, Suzuki upended the high-performance ATV hierarchy by releasing the industry’s first fully-suspended two-stroke quad, the LT250R Quadracer. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The 1980s were a great time to be a high-performance ATV enthusiast. Starting in 1981, with the introduction of Honda’s first ATC 250R, the ATV world exploded with high-performance offerings designed to cater to customers looking to do more than just putter through the back forty. Honda’s ATC 250R, Yamaha’s Tri-Z 250, and Kawasaki’s KXT250 Tecate delivered an exhilarating performance to those with the skill to harness their elevated potential.

In 1981, Honda created the high-performance ATV category with the introduction of their all-new ATC250R. Powered by a potent two-stroke engine and featuring full suspension front and rear, the ATC 250R was a quantum leap forward in performance over every other ATV that had proceeded it. Photo Credit: Macworth Vintage ATVs

In 1981, Honda created the high-performance ATV category with the introduction of their all-new ATC250R. Powered by a potent two-stroke engine and featuring full suspension front and rear, the ATC 250R was a quantum leap forward in performance over every other ATV that had proceeded it. Photo Credit: Macworth Vintage ATVs

Unfortunately, however, as the speeds and popularity of these three-wheeled ATVs increased, so did the scrutiny placed upon them by consumer advocacy groups. Many people outside (and some inside) the industry felt that the inherent instability of the three-wheeled platform made them unsuitable to be sold to consumers who were ill-prepared for their potentially treacherous nature.

With Honda holding many of the patents specific to ATC design, it was difficult for the other Big Four Japanese brands to break into the three-wheeled market. Seeing an opportunity to hit them where they weren’t, Suzuki added a fourth wheel in 1983 and effectivity rendered the ATC obsolete. Featuring a mildly tuned four-stroke engine and no suspension, the LT-125 Quadrunner was no threat to the likes of Honda’s ATC 200X and 250R, but its inherently more stable chassis and ease of use were immediately apparent to anyone who had ridden any of its three-wheeled competition. Photo Credit: Suzuki

With Honda holding many of the patents specific to ATC design, it was difficult for the other Big Four Japanese brands to break into the three-wheeled market. Seeing an opportunity to hit them where they weren’t, Suzuki added a fourth wheel in 1983 and effectivity rendered the ATC obsolete. Featuring a mildly tuned four-stroke engine and no suspension, the LT-125 Quadrunner was no threat to the likes of Honda’s ATC 200X and 250R, but its inherently more stable chassis and ease of use were immediately apparent to anyone who had ridden any of its three-wheeled competition. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1983, Suzuki introduced their answer to this ATV issue in the form of the LT-125 Quadrunner. Powered by a 124cc four-stroke single, this mildly tuned four-wheeler added a second wheel to the front of the chassis and changed the ATV world moving forward. With high-floatation balloon tires as its only suspension and very modest power output, the original Quadrunner was no threat to machines like Honda’s all-new ATC 200X in performance, but its inherently better stability made it an attractive alternative to the entry-level three-wheelers being offered by Honda, Kawasaki, and Yamaha at the time.

In 1984, the high-performance ATV category heated up with the introduction of the first competitor to Honda’s omnipotent 250R. The all-new Kawasaki KXT250 Tecate offered a sportier take on the 250R formula with a powerful liquid-cooled motor, motorcycle-style twist throttle, and more aggressive handling. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

In 1984, the high-performance ATV category heated up with the introduction of the first competitor to Honda’s omnipotent 250R. The all-new Kawasaki KXT250 Tecate offered a sportier take on the 250R formula with a powerful liquid-cooled motor, motorcycle-style twist throttle, and more aggressive handling. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Despite its limited performance potential, consumers and magazine editors alike were immediately taken with the Quadrunner’s improved handling and stability. The little quad proved a big hit and in 1984, Suzuki added a Quadrunner 50 and 185 to the lineup. Like the LT125, the new LT50 and LT185 were aimed at an entry-level market, but Suzuki had bigger plans in store for 1985.

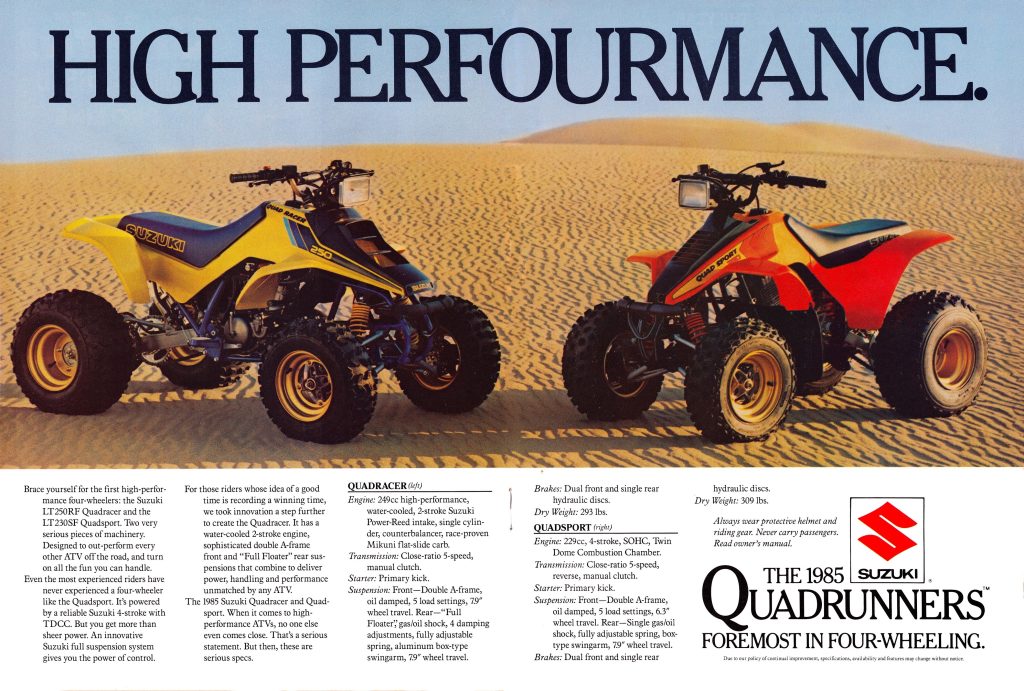

In 1985, Suzuki changed the ATV game forever with the launch of a pair of four-wheelers aimed directly at Honda’s dominant market position. The all-new LT250R Quadracer and LT230S Quadsport were not faster or better suspended than ATCs already on the market, but their superior stability gave them a handling advantage that was impossible to ignore. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1985, Suzuki changed the ATV game forever with the launch of a pair of four-wheelers aimed directly at Honda’s dominant market position. The all-new LT250R Quadracer and LT230S Quadsport were not faster or better suspended than ATCs already on the market, but their superior stability gave them a handling advantage that was impossible to ignore. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The 1985 season was a huge one for ATV enthusiasts with the introduction of Honda’s all-new liquid-cooled ATC 250R and big-bore four-stroke, the ATC 350X. Yamaha finally entered the high-performance ATV game in 1985 as well with the unveiling of the all-new Tri-Z 250. All three of these machines were praised for their excellent performance, but all three also suffered from the inherent limitations of the three-wheeled platform. High speeds and uneven terrain presented challenges to three-wheeled pilots that even the most talented and experienced riders could often find difficult to navigate safely. The new breed of high-performance three-wheelers was faster and had better handling than ever before, but they still required a tremendous amount of skill to operate safely.

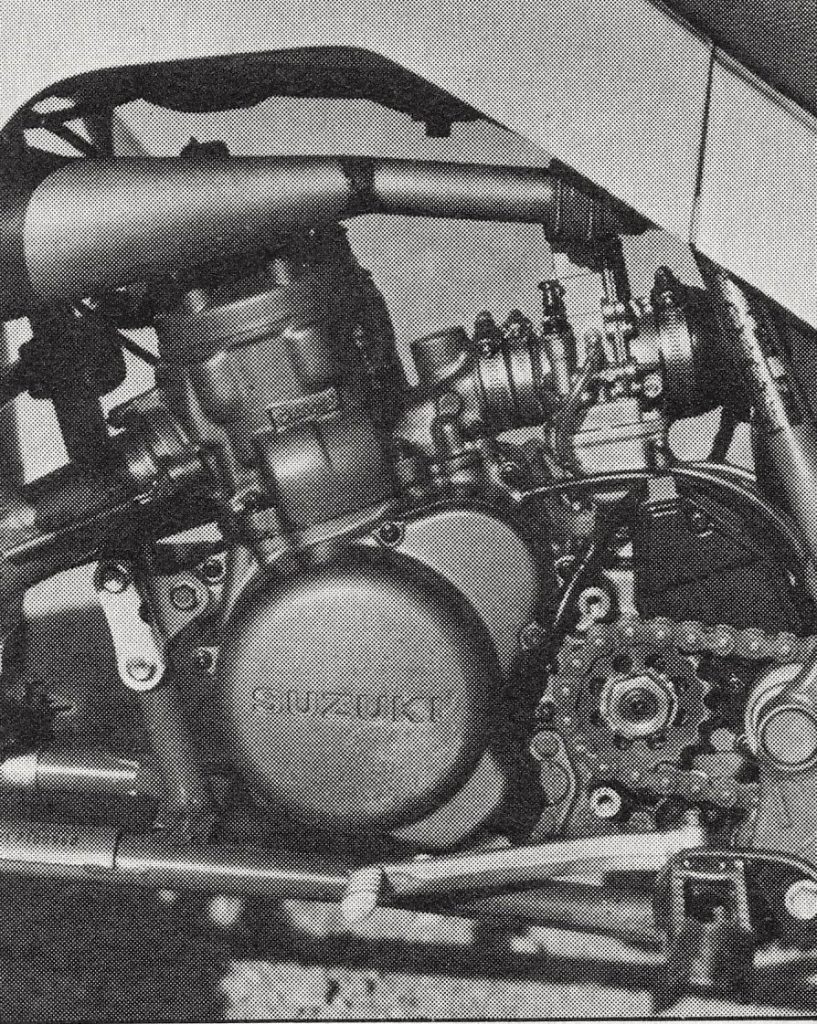

The 249cc liquid-cooled two-stroke motor employed on the new Quadracer looked like the engine found in the RM250 but it shared more in common with the mildly tuned dual-sport motor found in the street-legal RH250 in Japan. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

The 249cc liquid-cooled two-stroke motor employed on the new Quadracer looked like the engine found in the RM250 but it shared more in common with the mildly tuned dual-sport motor found in the street-legal RH250 in Japan. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

Just as the high-performance ATV market was heating up in 1985, Suzuki was once again preparing to reshape its landscape with the introduction of another revolutionary all-new machine – the LT250R Quadracer. Targeted at the enthusiast market, the Quadracer was a direct competitor to the Honda ATC 250R, Yamaha Tri-Z250, and Kawasaki KXT250 Tecate. Like its three-wheeled competitors, the new Quadracer employed a liquid-cooled two-stroke single for power, with a five-speed gearbox, primary kickstarting, and a manual clutch. While the motor looked a bit like the RM engines of the time with its works-like silver paint scheme, the engine shared most of its DNA with Suzuki’s Japanese market RH250 dual-sport motorcycle. That meant less horsepower than the motocross versions, but more versatility with a wider ratio gearbox and a counterbalancer to reduce vibration. The new motor displaced 249cc and employed Suzuki’s semi-case-reed “Power Reed” intake mated to a 32mm “flat slide” Mikuni mixer and Suzuki’s Pointless Electronic Ignition (PEI). A thumb throttle handled fuel delivery duties leaving the Tecate as the only performance ATV in the class to offer a motorcycle-like twist throttle as standard equipment. The top end of the motor lacked any sort of variable exhaust mechanism and was low-tech aside from its liquid cooling. Like the other ATVs in its class, its mission as a “do-it-all” machine dictated the use of a large spark-arrested muffler and a well-sealed but choked-off intake system. This kept the machine quiet and allowed it to handle water crossings with little issue but did hinder its maximum power output significantly.

In stock trim, the ’85 LT250R Quadracer was no fire breather, but its superior handling and stability made it more than a match for its three-wheeled competition in most situations. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In stock trim, the ’85 LT250R Quadracer was no fire breather, but its superior handling and stability made it more than a match for its three-wheeled competition in most situations. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

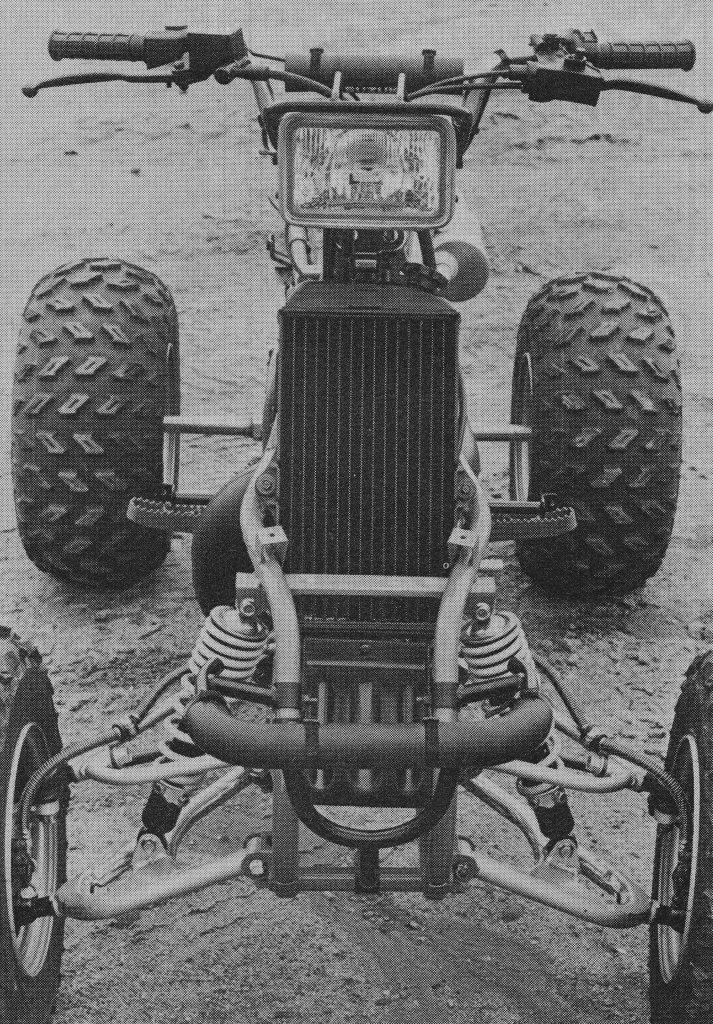

A massive single radiator, dual A-arms, and a powerful halogen headlight highlighted the front end of the all-new Quadracer in 1985. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

A massive single radiator, dual A-arms, and a powerful halogen headlight highlighted the front end of the all-new Quadracer in 1985. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

On the chassis front, the Quadracer broke new ground by replacing the single wheel and forks found on the competition with a set of dual wheels connected to the frame using a fully independent A-arm arrangement. Dual shocks handled the damping with 7.9 inches of travel available and spring preload as their only external adjustment. In the rear, the new Quadracer used a version of Suzuki’s Full Floater single-shock rear suspension to provide 7.9 inches of travel with a four-way rebound as its only external damping adjustment. A large box-section alloy swingarm provided strength and kept the weight down while powerful hydraulic triple-disc brakes allowed the Quadracer to dive to the inside line with ease. Despite its additional wheel, the new Quadracer’s weight was remarkably low with the machine clocking in a at very svelte 293 pounds. This was less than the Yamaha’s Tri-Z250 weighed in 1985 and only two pounds more than the class-leading ATC 250R. At 50.8 inches, the Quadracer’s wheelbase was slightly shorter than the Yamaha and Honda trikes, but .3 inches longer than the Kawasaki. In a nod to stability and steering precision, the front wheels of the Quadracer were spaced out as far as possible with the LT250R sitting wider at the front than in the rear. Previous Suzuki quads had placed the gas tank below the seat to keep the center of gravity as low as possible, but the addition of the Full Floater rear suspension necessitated a repositioning of the tank to a more traditional location. Like the other ATVs in the class, the Quadracer featured tall and narrow tires at the front and lower profile balloon tires at the rear.

In stock trim, the LT250R’s Power Reed motor produced a smooth and easy-to-manage flow of power from its 249cc. Most of its thrust was found in the midrange with decent torque down low and not much pull on top. Photo Credit: Mecum

In stock trim, the LT250R’s Power Reed motor produced a smooth and easy-to-manage flow of power from its 249cc. Most of its thrust was found in the midrange with decent torque down low and not much pull on top. Photo Credit: Mecum

On the track and trail, the all-new Quadracer was a revelation in handling performance. The addition of the second front wheel gave the Quadracer a tremendous advantage in stability and steering precision that was impossible to ignore. Even hard-core ATC enthusiasts were immediately impressed with the stability and predictability of the Suzuki platform. Off-cambers and uneven terrain that were treacherous to navigate on a three-wheeled ATV were complete no-drama affairs on the Quadracer. Off jumps, the Suzuki was a neutral flyer, and it was far more forgiving if you happened to get out of shape when landing. In the turns, it essentially went where it was pointed which was a significant improvement over the often-arcane handling manners of the trikes. At speed, it was exponentially more stable than its competitors and required far less body English to maintain control. In terms of handling, its only real disadvantage was the weight of its front end which made it more difficult to loft the front end over obstacles. Wheelies with the Quadracer were certainly possible, but it took a stronger tug at the bars and more throttle to get the front end off the ground.

On a track the Quadracer’s handling advantages became readily apparent with the four-wheeled platform handling uneven terrain much easier than its three-wheeled competition. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

On a track the Quadracer’s handling advantages became readily apparent with the four-wheeled platform handling uneven terrain much easier than its three-wheeled competition. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

Interestingly, this improved stability turned out to be the only real performance advantage the Quadracer had over its ATV competitors in 1985. The new motor was smooth and easy to ride but not particularly powerful. Low-end torque was decent, and the motor pulled well through the midrange but there was very little excitement once the RPMs climbed. The choked-off intake and exhaust and small 32mm carburetor (the RM250 used a 38mm mixer in ’85) produced a quiet, pleasant, and mellow spread of power that was fun but not particularly exhilarating. The counterbalancer quelled most of the motor’s vibration and the Suzuki was far more pleasant to be on than the balancer-less Yamaha and Kawasaki on a long ride. The clutch offered a light pull, but several riders commented that the Suzuki’s transmission was notchy and stubborn at times. Some riders also mentioned a disconcerting squeak emanating from the clutch basket under hard use in the dunes.

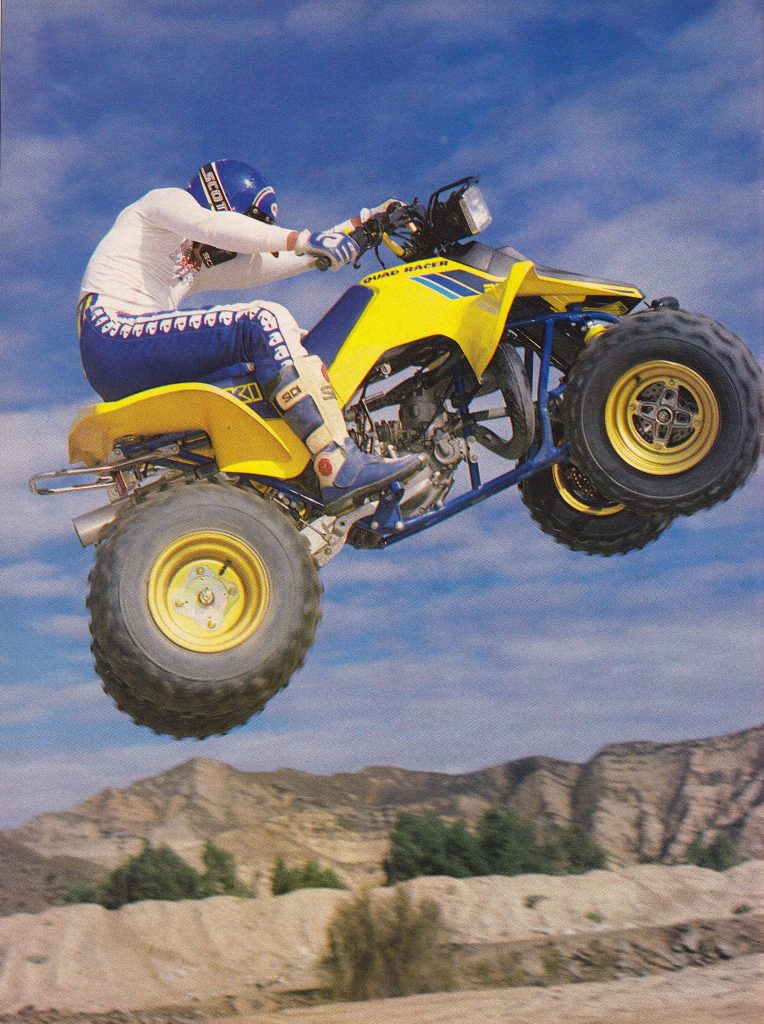

Getting out of shape on a jump was much less of a concern on the Quadracer than on any of its three-wheeled competitors in 1985. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

Getting out of shape on a jump was much less of a concern on the Quadracer than on any of its three-wheeled competitors in 1985. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

In terms of the ATV power hierarchy of 1985, the Quadracer sat towards the back of the pack. It was on par in potency with the Yamaha Tri-Z, but a step behind the hard-hitting Kawasaki and broad Honda. Most people felt the Honda’s 249cc six-speed mill offered the best combination of horsepower and usability, with the Kawasaki’s strong top-end appealing to the three-wheeled throttle jockeys. All four were plenty fast enough to be fun but if horsepower was your main concern the Quadracer was not going to blow off your boot gators.

The Kayaba front shocks on the Quadracer delivered 7.9 inches of travel and lacked any sort of external damping adjustment. Harsh in action and prone to bottoming on hard hits, they were one of the biggest disappointments with the Quadracer’s performance. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The Kayaba front shocks on the Quadracer delivered 7.9 inches of travel and lacked any sort of external damping adjustment. Harsh in action and prone to bottoming on hard hits, they were one of the biggest disappointments with the Quadracer’s performance. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the suspension front, the Quadracer was once again a middle-of-the-pack performer. None of the hot rod ATVs available in 1985 offered the same sort of suspension sophistication found on their motocross cousins, but one definitely did a better job of smoothing out the bumps than all the others. For most riders, it was the ATC 250R with its beefy 39mm front forks and Pro-Link rear that did the best job of taking the bite out of the track in 1985. With a class-leading 9.8 inches of travel front and rear and well-sorted damping, the Red Rooster lapped the field with an excellent combination of comfort and control.

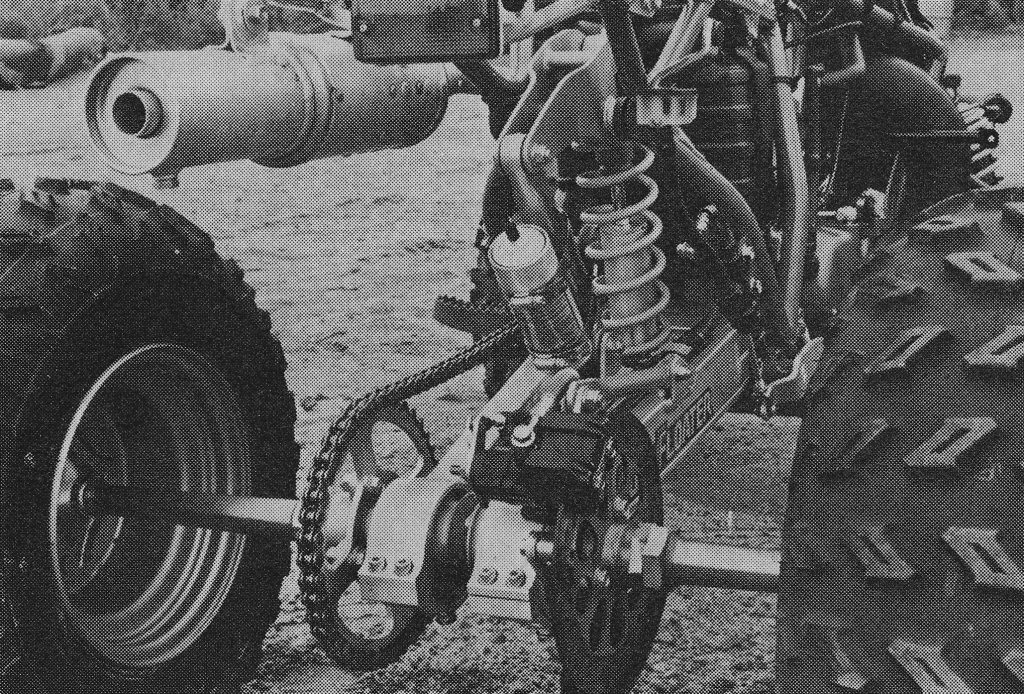

In the rear, the Quadracer employed a custom version of their unique Full Floater rear suspension system. Not as sophisticated as the shocks found on their RMs, the Quadracer’s Kayaba damper lacked a compression damping adjuster and only offered four settings for rebound control. While its action was better than the front shocks, most pilots found its performance disappointing. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

In the rear, the Quadracer employed a custom version of their unique Full Floater rear suspension system. Not as sophisticated as the shocks found on their RMs, the Quadracer’s Kayaba damper lacked a compression damping adjuster and only offered four settings for rebound control. While its action was better than the front shocks, most pilots found its performance disappointing. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

Moderately-sized jumps were taken in stride, but major sky shots were inadvisable with the Quadracer’s stock suspension in place. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

Moderately-sized jumps were taken in stride, but major sky shots were inadvisable with the Quadracer’s stock suspension in place. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

With only 7.9 inches of travel and no adjustments aside from spring preload available, the front shocks on the Quadracer were painfully average performers. Harsh at low speed and prone to bump-steer, the front end of the Quadracer transmitted far more of the track to the rider’s wrists than most pilots appreciated. Serious leaps showed the limits of their modest performance and most riders considering racing their Quad would have been well advised to consider aftermarket upgrades.

Big fun is what ATVs are all about and the new Quadracer was an excellent partner for playing in the sand, snow, and mud. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

Big fun is what ATVs are all about and the new Quadracer was an excellent partner for playing in the sand, snow, and mud. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

In the rear, the Full Floater showed much better performance with a decent ride that worked well under most circumstances. Its relative lack of travel held it back in comparison to the excellent Honda Pro-Link, but for most applications shy of the track it was a good performer. The overall ride of the rear shock was much smoother than the front units and most riders could find an acceptable setting with its limited adjustments. Just as with the front, big jumps could overwhelm its stock settings, but the machine was never intended for racing in stock condition. If racing was in your plan, the Floater’s heavy rebound could become an issue as it tended to pack down on repeated hits. For trail riding and playing in the dunes, this was no issue, but any decently long set of whoops was likely to flummox its overzealous damping.

Thumb throttles were never on the list of most pilots’ favorite ATV features and the Quadracer’s was one of the worst in the class in 1985. Its heavy return spring assured things got shut down quickly upon its release, but also gave riders cramps in their right hand on long rides. Photo Credit: Mecum

Thumb throttles were never on the list of most pilots’ favorite ATV features and the Quadracer’s was one of the worst in the class in 1985. Its heavy return spring assured things got shut down quickly upon its release, but also gave riders cramps in their right hand on long rides. Photo Credit: Mecum

On the detailing front, the Quadracer proved very good overall. The under-stressed motor was reliable and held up well to abuse in stock condition. For those looking for more power, replacing the stock exhaust, rejetting the carb, and opening up the airbox unlocked a significant amount of performance without impacting reliability. The Quadracer’s new bodywork was handsome, and most riders found its ergonomics spacious and comfortable. The stock thumb throttle was panned by nearly everyone and several testers commented that its return spring was far too strong, leading to premature thumb fatigue. Even without a battery, the standard halogen headlight worked well and the Quadracer was a ton of fun to ride long after the motocross guys headed back to the truck. The stock alloy silencer was super trick and a nod to the machine’s performance intentions. It was slightly louder than the steel units found on the competition but much lighter and still off-road legal. The triple-disc brakes worked extremely well, and several testers commented that they wished the RMs had come with similarly powerful units. Underbody protection was all but nonexistent with the only coverage being a flimsy cover for the rear rotor. Bent sprockets, busted rotors, and cracked cases were a major concern for anyone planning to ride their Quadracer in a rocky environment. Unless you only rode in the dunes, aftermarket skid plates were a must.

In 1985, all the Big Four Japanese manufacturers had high-performance ATVs looking to claim your hard-earned dollars. Honda remained the King of the three-wheelers, but even the most jaded of ATC enthusiasts had to admit there was a new sheriff in town. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

In 1985, all the Big Four Japanese manufacturers had high-performance ATVs looking to claim your hard-earned dollars. Honda remained the King of the three-wheelers, but even the most jaded of ATC enthusiasts had to admit there was a new sheriff in town. Photo Credit: Dirt Wheels

Even with a bit of bump steer to deal with the all-new Quadracer was the best-turning ATV available in 1985. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Even with a bit of bump steer to deal with the all-new Quadracer was the best-turning ATV available in 1985. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the final analysis, the Quadracer’s mild-mannered motor and mediocre suspension were not nearly enough to overshadow its inherent handling advantages. Despite being slower and harsher in the rough than Honda’s ATC 250R, the Quadracer proved nearly unbeatable on the track. It was easier to ride slow, safer to ride fast, and impressively light despite the added complexity of its four-wheeled layout. Even long-time ATC devotees found its charms difficult to overlook. Within two years of the Quadracer’s debut, the high-performance three-wheeler would be all but a memory with Kawasaki finally retiring the KXT250 Tecate in 1987. Even without government pressure, however, the excellence of Suzuki’s inspired design was hard to ignore, and the market would have certainly moved toward a four-wheeled future in short order. Bold, innovative, and game-changing, Suzuki’s 1985 Quadracer stands as one of the truly iconic machines from the golden age of high-performance ATVs.

The 1980s were an era of big changes in the ATV world and very few machines had as big of an impact on the industry as Suzuki’s revolutionary Quadracer. Part racer and part plaything, the Quadracer pointed the way forward for an industry embroiled in controversy and helped assure the joys of sporting ATVs would continue to be enjoyed for many decades to come. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The 1980s were an era of big changes in the ATV world and very few machines had as big of an impact on the industry as Suzuki’s revolutionary Quadracer. Part racer and part plaything, the Quadracer pointed the way forward for an industry embroiled in controversy and helped assure the joys of sporting ATVs would continue to be enjoyed for many decades to come. Photo Credit: Suzuki