For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the magazine shootouts for the 125 class of 2001.

The 125 class was still alive and thriving in 2001, but there was a troubling rumbling on the horizon. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The 2001 season stands as one of the most momentous in the history of modern motocross. That season, Yamaha upended the power structure in the 125 class by introducing the very first YZ250F four-stroke. Yamaha’s super thumper took advantage of the AMA’s questionable displacement rules to deliver a one-two punch to the tiddler division. While the YZ-F’s peak horsepower figures were not out of line with the top 125s of the time, its ultra-wide powerband and excellent bottom-end torque certainly were. It was faster out of corners, easier to ride, and smooth as glass. With the arrival of the YZ250F, every two-stroke in the class was put at a significant disadvantage.

The original Yamaha YZ400F was a huge hit, but its impact on the sport was nothing compared to the knockout punch the YZ250F delivered to the 125 class in 2001. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The original Yamaha YZ400F was a huge hit, but its impact on the sport was nothing compared to the knockout punch the YZ250F delivered to the 125 class in 2001. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While the new YZ250F was certainly a game-changer, it remained an outlier in a class full of screaming 125s. In 2001, it was the sole 250F on the market and only MXA included it in their 125 shootout. At the time, many people still considered the four-stroke Yamaha a bike without a class and it was not clear how the Yamaha thumper would fit into racing moving forward. With that in mind, Dirt Bike, Dirt Rider, Transworld MX, and Cycle News all excluded the YZ250F from their 2001 125 shootouts. While it is impossible to know exactly how the YZ250F would have fared in those contests, it is a fair bet that the four-stroke would have been very hard to beat.

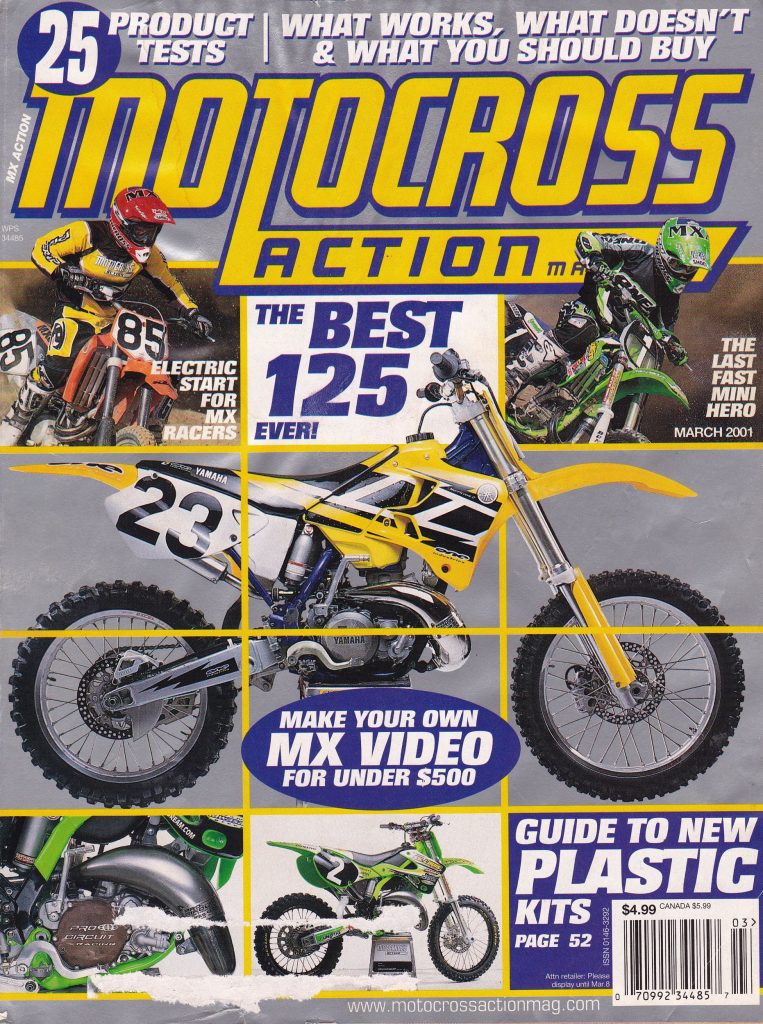

Motocross Action was the only major magazine to include Yamaha’s four-stroke “cheater” bike in its 125 shootout for 2001. Photo Credit Motocross Action.

Motocross Action was the only major magazine to include Yamaha’s four-stroke “cheater” bike in its 125 shootout for 2001. Photo Credit Motocross Action.

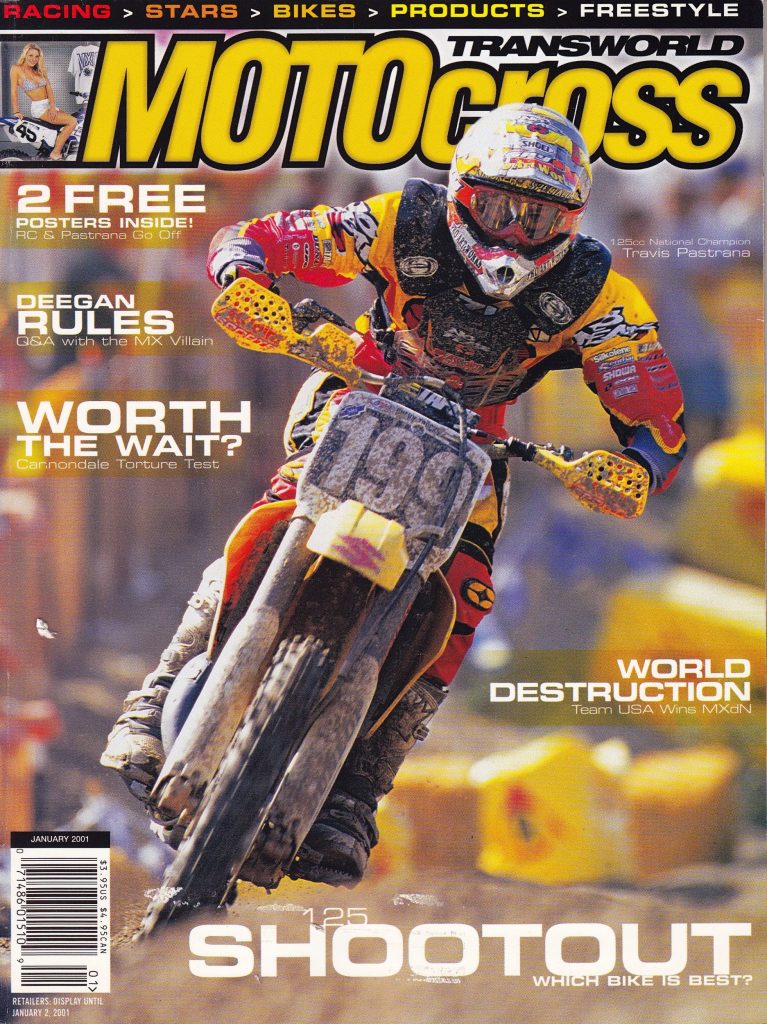

Transworld MX’s shootout stuck to the Big Four Japanese 125 competitors and KTM in 2001: Photo Credit: Transworld MX

Transworld MX’s shootout stuck to the Big Four Japanese 125 competitors and KTM in 2001: Photo Credit: Transworld MX

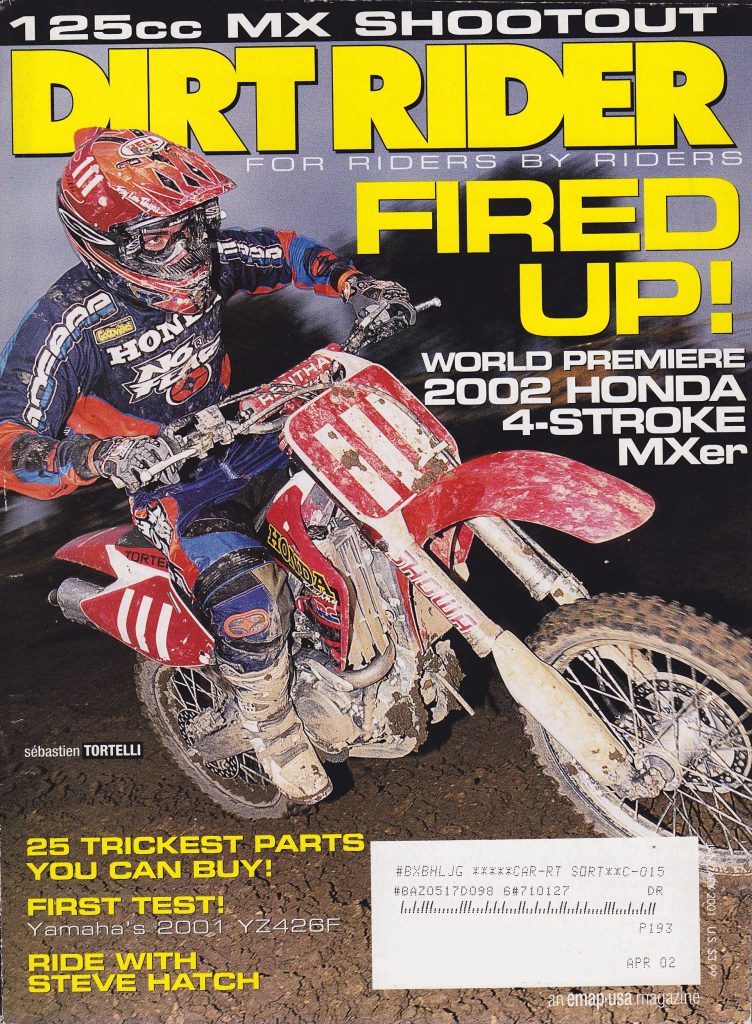

Dirt Rider opened things up a bit by adding Husqvarna’s CR125 to the shootout mix in 2001. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Dirt Rider opened things up a bit by adding Husqvarna’s CR125 to the shootout mix in 2001. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

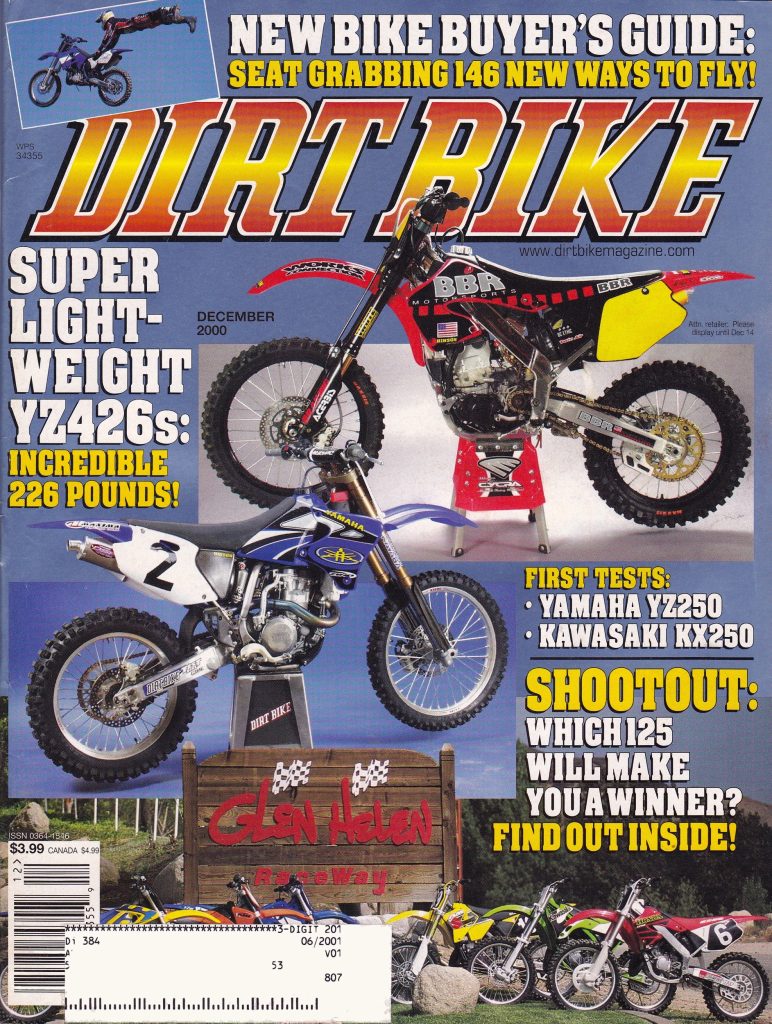

Like Dirt Rider, Dirt Bike allowed Austria’s KTM and Italy’s Husqvarna to come to play with the Japanese 125s in 2001.

Like Dirt Rider, Dirt Bike allowed Austria’s KTM and Italy’s Husqvarna to come to play with the Japanese 125s in 2001.

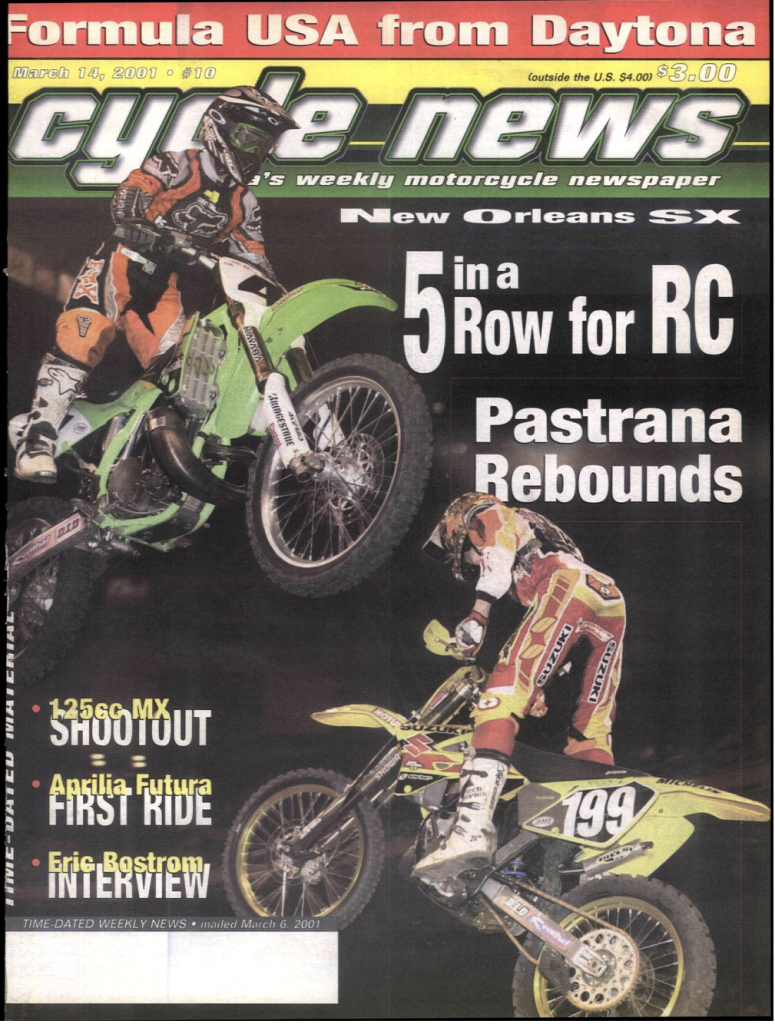

Cycle News offered the most wide-ranging 125 shootout in 2001 with three Europeans taking on the traditional Japanese tiddlers. Photo Credit: Cycle News

Cycle News offered the most wide-ranging 125 shootout in 2001 with three Europeans taking on the traditional Japanese tiddlers. Photo Credit: Cycle News

For those unwilling to take the four-stroke plunge in 2001, there was still a great selection of very competitive 125 machines available. Honda, Kawasaki, Yamaha, and Suzuki all offered updated racers, with the Suzuki featuring the most changes for 2001. Over in Europe, Austria’s KTM, Italy’s TM, and Italy’s Swedish import Husqvarna provided riders with a taste for the exotic an alternative to the ubiquitous Japanese. In the right hands, any of them could win, but three of the machines in 2001 made that task easier.

Here is a look back at the 125 class of 2001 and how the machines stacked up in the enthusiast magazines of the time.

2001 Yamaha YZ250F Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 1st (out of 6) Dirt Bike – N/A Dirt Rider – N/A Transworld MX – N/A Cycle News – N/A Photo Credit: Yamaha

2001 Yamaha YZ250F Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 1st (out of 6) Dirt Bike – N/A Dirt Rider – N/A Transworld MX – N/A Cycle News – N/A Photo Credit: Yamaha

Relatively light, super smooth, excellent handling, and blessed with a powerband as wide as Montana, Yamaha’s baby thumper changed people’s perception of what a small four-stroke could do. Photo Credit: Corey Neuer

Relatively light, super smooth, excellent handling, and blessed with a powerband as wide as Montana, Yamaha’s baby thumper changed people’s perception of what a small four-stroke could do. Photo Credit: Corey Neuer

2001 Yamaha YZ250F Overview: Before the introduction of Yamaha’s YZ250F, the thought of a truly competitive 250 four-stroke seemed like a valve-and-cam lover’s pipe dream. No one outside of Yamaha’s testing department took it seriously, least of all the AMA. In a world filled with modified XRs, DRs, and KLXs, a 250cc four-stroke displacement limit seemed perfectly reasonable in the 125 class. Even fully modded 250 four-strokes had a difficult time keeping a good-running 125 in their sights.

With the introduction of the YZ250F, however, that double displacement advantage seemed more like a lack of foresight than any real attempt at parity. The Yamaha’s road race-inspired five-valve 249cc power plant delivered far more power and torque than any production 250 four-stroke ever had. It was 15-17 pounds heavier than its 125 competition, but that felt like less of a penalty on the 250F than it did on the sometimes unwieldy YZ400F/YZ426F. Racing 125s were light, fun, and fast, but none of them possessed the 250F’s unbeatable combination of low-end grunt and limitless rev. One ride on the YZ250F was usually enough to convince most riders that it had no business racing in the 125 class.

Fairness debates aside, there was no denying the fact that Yamaha’s revolutionary 250F was one phenomenal racing motorcycle. Its motor was smooth, powerful, and incredibly flexible. Its suspension was well sorted and its chassis was remarkably precise. Riders loved Yamaha’s comfortable ergonomics, razor-sharp turning, and rock-solid stability. The motor was bulletproof and the whole bike was built with Yamaha’s typical attention to detail. Its only real downsides were its sometimes problematic starting and a sinking feeling that you were getting away with something by racing it against true 125s. As long as you did not stall it, it was as close to cheating as any self-respecting racer could get. Many riders still preferred the sound, smell, and feathery feel of a screaming 125, but the results on the track would quickly prove that the YZ250F broke the 125-class paradigm in a way that the original YZ400F had not.

2001 Suzuki RM125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 3rd (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 1st (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 1st (out of 6) Transworld MX – 1st (out of 5) Cycle News – 2nd (out of 6) Photo Credit: Suzuki

2001 Suzuki RM125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 3rd (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 1st (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 1st (out of 6) Transworld MX – 1st (out of 5) Cycle News – 2nd (out of 6) Photo Credit: Suzuki

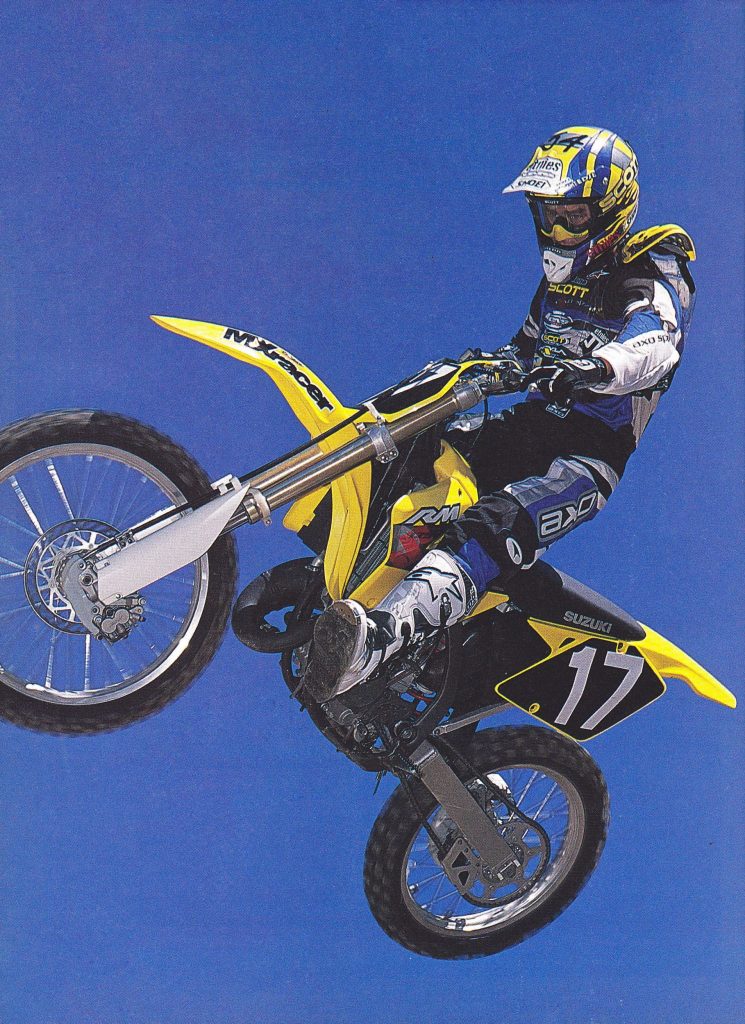

All-new from the ground up, the Suzuki RM125 was the very definition of what made a 125 great in 2001. Photo Credit: MX Racer

All-new from the ground up, the Suzuki RM125 was the very definition of what made a 125 great in 2001. Photo Credit: MX Racer

2001 Suzuki RM125 Overview: In 2001, Suzuki’s RM125 was coming off a 125 National Motocross championship with Travis Pastrana at the controls. The Wunderkind of motocross made the five-year-old RM look like a world beater, but its performance in stock condition was less unanimously praised. Experts loved its stratospheric revs, but those of lesser talent struggled with its demanding powerband, nervous handling, and cramped feel. In a class dominated by the chunky powerbands of Yamaha and KTM, the RM’s old-school screamer personality seemed like a throwback to a 125 era whose time had passed.

In 2001, Suzuki scrapped everything about the old RM125 platform and dialed up an entirely new design. The new bike featured an innovative “semi-perimeter” frame, redesigned motor, revamped suspension, and flashy new “Champion Yellow” bodywork. The new layout was super slim and very comfortable with lots of room to climb all over the bike. Styling was drop-dead gorgeous with a modern look that made the old machine appear like the throwback to the nineties that it was. The new bike was lighter, faster, and much better suspended with a solid powerband and the best turning in the class. The new motor offered better torque than the 2000, but it was still no match for the Yamaha and KTM in the midrange. As before, its best work was done on top where the RM pulled and pulled until your right wrist ran out of throttle to twist.

Riders loved the RM’s ultra-light feel, excellent ergonomics, plush suspension, silky-smooth clutch, effortless jumping, and strong powerband. For Dirt Bike, Dirt Rider, and Transworld MX, this was enough to propel the screaming yellow zonker to the top of the 125 division. For MXA and Cycle News, the RM’s nervous high-speed handling and less pronounced hit placed it behind its brawnier blue rival.

2001 Yamaha YZ125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 2nd (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 2nd (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 2nd (out of 6) Transworld MX – 2nd (out of 5) Cycle News – 1st (out of 6) Photo Credit: Yamaha

2001 Yamaha YZ125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 2nd (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 2nd (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 2nd (out of 6) Transworld MX – 2nd (out of 5) Cycle News – 1st (out of 6) Photo Credit: Yamaha

After five years at the top, Yamaha made a bid for more top-end in 2001 that some felt reduced its overall appeal. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

After five years at the top, Yamaha made a bid for more top-end in 2001 that some felt reduced its overall appeal. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

2001 Yamaha YZ125 Overview: Long the whipping boy of the 125 class, Yamaha’s YZ125 made a major leap to the front of the class in 1996. The all-new machine offered a broad and torquey powerband that made going fast easy. Over the next five years, Yamaha rode this power advantage to a string of impressive victories on the track and in the press. The YZ’s remarkable motor and excellent do-it-all chassis made it the 125 to beat at the tail end of the last century.

In 2001, Yamaha decided to chase a bit more top end for their 125 powerhouse by reconfiguring the porting, moving to a six-peddle carbon fiber reed valve, and upping the size of the carburetor by 2mm. The new 38mm TMX was the same size mixer found on the YZ250 and Yamaha hoped it would give the YZ the firepower to outgun KTM’s new horsepower champ – the 125SX.

The result of these changes was a YZ125 that delivered a stronger and longer pull on top, but less punch down low. The bike was by no means as difficult to ride as some of its competitors, but it was more challenging than in the past. It was no longer just enough to grab a handful of throttle to get the YZ going out of turns. This new power plant required a healthy stab of the clutch and more careful gear selection to get the party going. The less forgiving powerband was no issue for experts, who enjoyed the added boost on top, but less experienced riders could find the new power profile frustrating.

While the new motor proved somewhat polarizing, the rest of the YZ was aces in 2001. The suspension was excellent with a plush feel and good control. The brakes stopped on a dime and the front end went exactly where it was pointed. It was not quite as sharp in the turns as the scalpel-like RM, but it was far more predictable at speed. Overall, it was an excellent bike that was just a bit harder to ride than in the past. For Cycle News and Motocross Action, that was enough to land the YZ in the top true 125 spot of 2001. For Dirt Bike, Dirt Rider, and Transworld MX, the YZ’s new more demanding personality was enough to slot it behind the all-new RM in the final standings.

2001 KTM 125SX Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 4th (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 3rd (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 4th (out of 6) Transworld MX – 5th (out of 5) Cycle News – 3rd (out of 6) Photo Credit: KTM

2001 KTM 125SX Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 4th (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 3rd (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 4th (out of 6) Transworld MX – 5th (out of 5) Cycle News – 3rd (out of 6) Photo Credit: KTM

KTM’s 2001 125SX lacked the handling finesse of many of its rivals but made up for it with gobs of berm-bashing horsepower. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

KTM’s 2001 125SX lacked the handling finesse of many of its rivals but made up for it with gobs of berm-bashing horsepower. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

2001 KTM 125 SX Overview: In 2001, KTM had been a legitimate contender for the best 125 in the land. Its PDS “no-link” rear suspension was mediocre, and its chassis was unrefined, but its 124.8cc case-reed mill was so fast that many riders were willing to overlook its other shortcomings. For riders who prioritized power over all else, the KTM offered a compelling 125 package.

For 2001, KTM dialed up an all-new motor, revamped suspension, and a redesigned pilot’s compartment in a bid to finally topple the Big Four’s stranglehold on the 125 division. The new motor maintained its case-reed configuration but rejiggered the bore and stroke to match the European works machines of Jamie Dobb and Grant Langston. The new motor featured a lighter crank, new porting, and a redesigned piston. Chassis changes were limited to a revamped setting for the 43mm WP forks and PDS shock while all-new bodywork cleaned up the looks and slimmed down the ergos.

Thankfully for KTM fans, the motor changes for 2001 did nothing to diminish the Katoom’s reputation for horsepower. Unlike some manufacturers, who chose to chase the YZ125’s wide powerband, the men from Mattighofen took the approach of focusing on what they did best. For KTM, that meant a mid-and-up power curve that came on strong in the midrange and pulled hard on top. There was not a lot of grunt down low, but if you feathered its excellent hydraulic clutch the KTM snapped to life and flat ripped. On the dyno, it pumped out two more peak horsepower than the YZ125 and a full three ponies more than the highly-regarded RM. It even outpowered the all-new YZ250F four-stroke on the dyno. Torque of course was another matter, but in the peak pony race, the KTM was king in 2001.

On the track, that horsepower advantage was immediately apparent and everyone who rode the Austrian commented on its remarkable power. The orange machine rocketed out of corners and howled up steep hills. The hydraulic clutch meant no adjustments in the heat of battle and the transmission, while not silky smooth, was improved and more than capable of catching the next cog when necessary. Add in the easiest airbox access and you had what most people considered to be by far the best 125 motor package available in 2001.

As to the rest of the KTM’s performance, it was not as unanimously loved as its motor. The WP forks and PDS no-link shock continued to rank last among its competitors. The shock felt both stiff and was prone to harsh bottoming. The forks transmitted way too much of the track through the trick Magura fat bars and were generally far busier feeling than riders liked. The KTM was super light and felt that way on the track, but its overall handling was disappointing in most respects. The front end felt disconnected from the rest of the chassis, and it was hard to trust it in low-traction situations. Stability was also not a standout with the KTM being prone to unpredictable fits of headshake from time to time. These issues were less of a problem than they would have been on a heavier and more powerful machine, but they did detract from the KTM’s overall appeal.

On the plus side was the KTM’s new bodywork which was slimmer and more handsome than before. Riders liked the new riding position but continued to complain about the concrete KTM tried to pass off as seat foam. The Magura oversized alloy bars were super trick, the hydraulic clutch was sano, the plated pipe was durable, and the Brembo brakes stopped the orange missile with authority. The rims, sprockets, and chain were also a cut above the typical Japanese fare in quality.

With all this going for it the best the KTM could manage was a third overall in any of the final standings. Even riders who gave the KTM a perfect 10 for motor performance could not find a way to overlook its other peccadillos. MXA, Dirt Bike, and Cycle News ranked it as the third-best 125 available in 2001, but even those magazines who slotted it lower conceited that the excellent motor was hard to overlook. Unfortunately, however, even in a class where the motor is everything, you need a little help from the chassis to harness all of those wild ponies.

2001 Honda CR125R Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 5th (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 5th (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 3rd (out of 6) Transworld MX – 4th (out of 5) Cycle News – 4th (out of 6) Photo Credit: Transworld MX

2001 Honda CR125R Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 5th (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 5th (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 3rd (out of 6) Transworld MX – 4th (out of 5) Cycle News – 4th (out of 6) Photo Credit: Transworld MX

Well suspended, with excellent handling and beautifully built, Honda’s CR125R had everything but the horsepower to take the class by storm in 2001. Photo Credit: Transworld MX

Well suspended, with excellent handling and beautifully built, Honda’s CR125R had everything but the horsepower to take the class by storm in 2001. Photo Credit: Transworld MX

2001 Honda CR125R Overview: Once the purveyors of the fastest 125s in the land, Honda and their iconic CR125 fell on hard times in the late nineties. Starting with the switch to an aluminum frame in 1998, the once fire-breathing alpha male of the class was turned into an asthmatic 207-pound weakling. Add in a chassis that buzzed, bucked, and beat you to death and harsh suspension and you had a recipe for one of the most precipitous falls from grace in modern motocross history.

Knowing they had made a major misstep in 1998 with the first-generation alloy-framed CR125R, Honda set about fixing the little CR’s many failings in 2000. The second-generation alloy frame was more compact, less rigid, and designed to bring back some of the legendary turning prowess that was neutered by the first-generation alloy chassis. An all-new motor finally retired the Honda Power Port in use since 1990 and went with a road-race inspired “flapper valve” design cribbed from their NSR Grand Prix machine. The all-new bodywork, revamped suspension, and a slight color change finished off the reimagined CR125R for 2000.

On the track, the new CR turned out to be a huge improvement in every way but one. The new chassis handled great, and the suspension provided some of the best performance in the class. The redesigned frame was far less harsh, and everyone praised the CR’s comfortable feel. About the only thing that turned out to be disappointing was the motor, which continued to pale in comparison to its rivals. The new motor hit hard in the middle but offered very little at the extremes. Its midrange punch was fun, but it was very hard to keep the Honda in its narrow sweet spot on the track. Shift too soon, and it bogged. Shift too late, and it stopped pulling like the spark plug wire fell off. If you could keep it pinned and row the gearbox like a man possessed, then the Honda was competitive, but there were far easier ways to go fast in 2000.

For 2001, Honda looked to up the competitiveness of their one-two-five by increasing the size of the air intakes into the airbox by 20%, enlarging the intake tract, redesigning the reed valve (four pedals instead of six), reconfiguring the porting, lengthening the stroke of the power valve governor, reshaping the flapper valve, bolting on a new exhaust pipe, and adding 8% of additional mass to the flywheel. On the chassis front the alloy frame was adjusted to offer a half-degree slacker head angle and the suspension was updated with all-new valving, a stiffer set of springs up front, and an inch shorter shock in the rear.

Thankfully for the Honda faithful, these changes added up to an improved 125 machine. The motor changes for ’01 broadened the CR’s pull with a longer powerband that no longer fell off a cliff past the midrange. The top-end pull was no threat to a KTM (or probably a 1997 CR125R either), but there was enough there to get the job done if you needed to leave it on just a bit longer. Low-end power remained nonexistent with the CR requiring lots of clutch and more skill out of turns than most of its rivals. Lowering the gearing helped but the Honda was never going to be as easy to ride as the YZ or RM. As in the past, the shifting and clutch action on the Honda were flawless, but the continued use of a five-speed transmission puzzled testers.

The updated suspension and chassis were roundly praised, and many testers felt the Honda was the most comfortable bike in the class with its excellent ergonomics, quality components, and comfy seat. There was still a bit too much vibration coming through the alloy frame, but everything you touched, turned or twisted felt like it was built to last.

In the end, the Honda’s placing came down to one factor – power. Everything about the red machine except its motor was at or near the top of the class, but that one factor was just too much of a handicap in the eyes of most of the magazine testers. If it had had more bottom and a stronger pull on top it would have been the best 125 in the land, but as it was, the Honda was a very fun and super well-built bike that was not quite up to bringing back the glory days of Big Red in the 125 class.

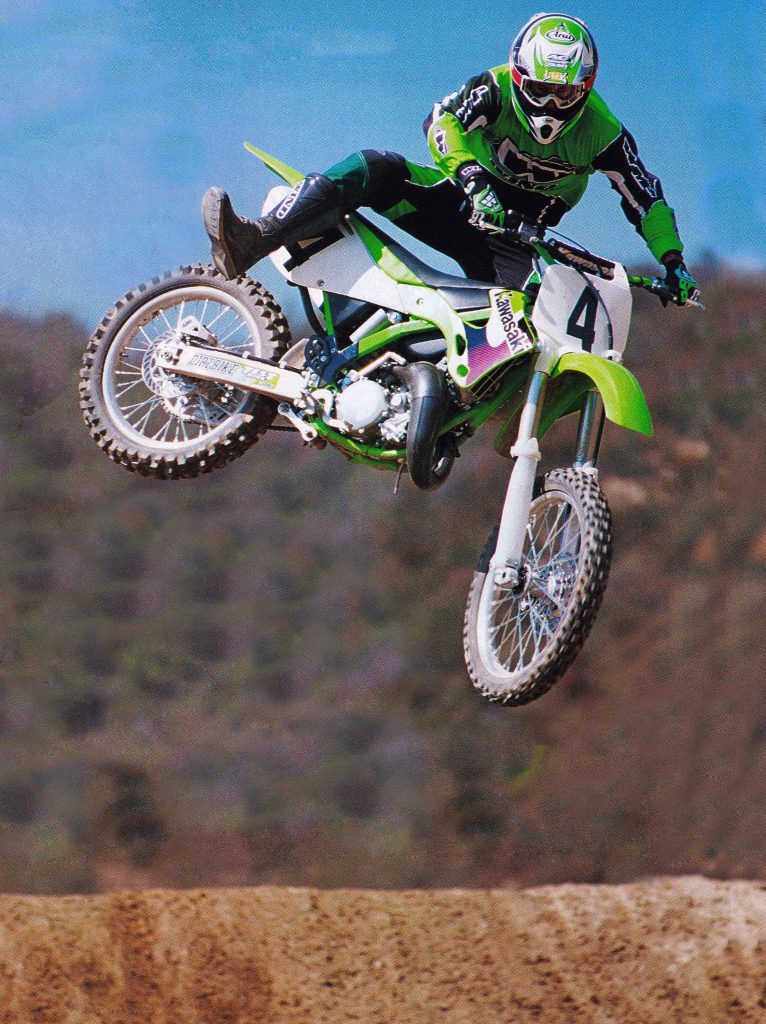

2001 Kawasaki KX125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 6th (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 4th (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 5th (out of 6) Transworld MX – 3rd (out of 5) Cycle News – 5th (out of 6) Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

2001 Kawasaki KX125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 6th (out of 6) Dirt Bike – 4th (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 5th (out of 6) Transworld MX – 3rd (out of 5) Cycle News – 5th (out of 6) Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Kawasaki’s KX125 was one of the winningest machines of the late nineties and early 2000s despite the stock machine’s inability to capture shootout victories. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Kawasaki’s KX125 was one of the winningest machines of the late nineties and early 2000s despite the stock machine’s inability to capture shootout victories. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

2001 Kawasaki KX125 Overview: Throughout the nineties and early 2000s, Kawasaki’s KX125 was one of the winningest machines in motocross. Multiple AMA National and Supercross titles attested to the potential offered by Kawasaki’s little green machine, but that professional success rarely translated to victories in the enthusiast press. With Mitch Payton’s motor wizardry and Ricky Carmichael’s riding skill the KX was a winner, but in stock condition, it was an often-flawed package.

In 2000, the KX125 offered a short and punchy powerband very similar to the one found on the CR125. When it was on the pipe, the green machine was fast, but that burst was very short in duration. The hard-hitting powerband was fun to ride but difficult to use in the heat of battle. Its larger overall size, lackluster turning, and mushy brakes also hindered its appeal to many. The KX offered potential, but you needed a skilled tuner to sand off its rough edges.

For 2001, Kawasaki dialed up several engine changes aimed at broadening the KX’s narrow powerband. New cases increased primary compression and repositioned the carburetor to be closer to the crank. An all-new cylinder featured updated porting, a better-sealing KIPS valve, and slightly more compression. The flywheel was lightened and a new ignition curve was installed to work with the revamped motor settings. The power jet Keihin carburetor of 2000 was retired in favor of a conventional 36mm Mikuni and the silencer was shortened by two inches.

On the chassis front, the 2001 KX125 was largely a carryover over with the only significant changes being a new linkage, straight-rate shock spring, stiffer fork springs, and an assortment of upgrades for the front and rear calipers. The frame, bodywork, and even the graphics remained largely unchanged from the year before.

In the end, the engine changes made for 2001 did improve the KX’s powerband slightly, but it remained narrower than most of its rivals. The new motor picked up a bit sooner off the bottom and pulled a tiny bit farther on top, but most of its power remained dead center in the power curve. Gearing it down helped slightly, but it was never going to snap out of turns like the orange, blue, or yellow machines.

The updated suspension worked better than in 2000 but some riders noted that the chassis felt unbalanced with the forks feeling stiffer than the shock. The KX’s big bike feel and slow handling also felt out of step in a class dominated by quick-twitch carvers. If you were tall, fast on the shifter, and hated headshake, then the KX had something to offer, but that narrow demographic limited its appeal in the final shootout standings. A few of the magazines rated it above the similarly horsepower-impaired Honda, but none of them were willing to place the KX above the more potent RM and YZ.

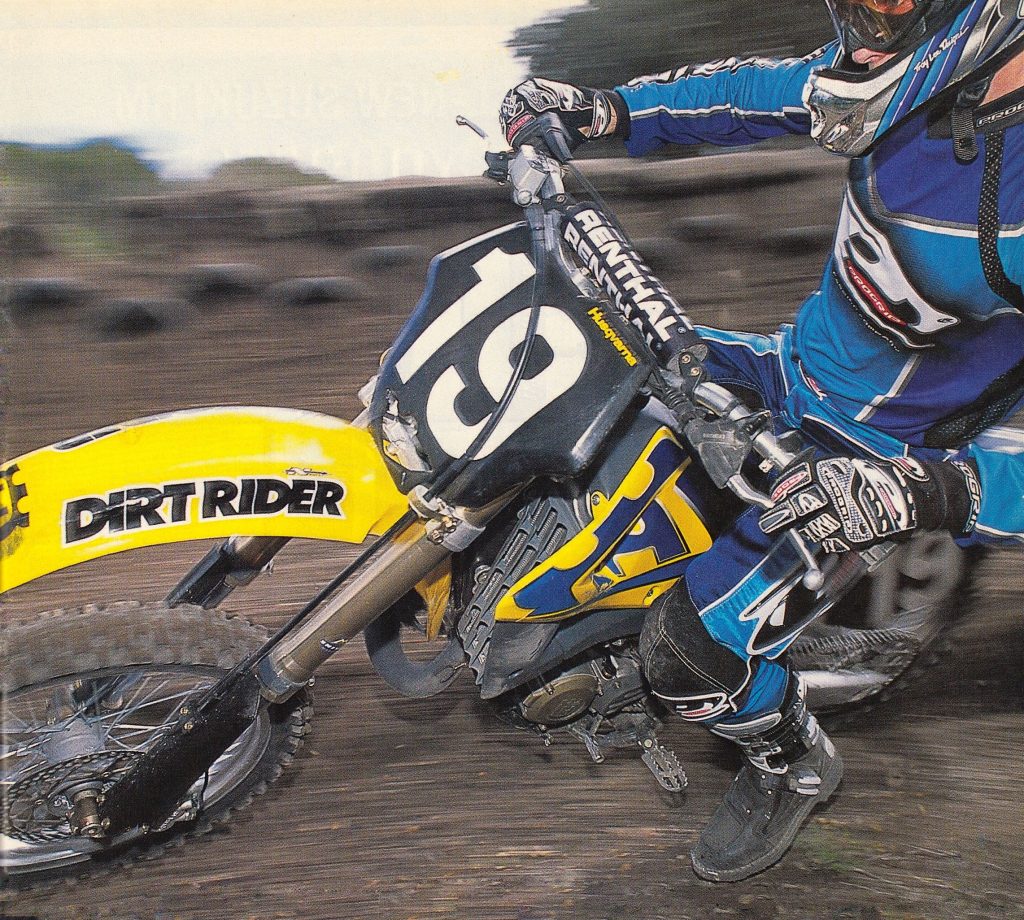

2001 Husqvarna CR125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – N/A Dirt Bike – 6th (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 6th (out of 6) Transworld MX – N/A Cycle News – N/A Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

2001 Husqvarna CR125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – N/A Dirt Bike – 6th (out of 6) Dirt Rider – 6th (out of 6) Transworld MX – N/A Cycle News – N/A Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

High-quality components and Italian workmanship were not enough to win over the majority of magazine testers to the Husqvarna camp in 2001. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

High-quality components and Italian workmanship were not enough to win over the majority of magazine testers to the Husqvarna camp in 2001. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

2001 Husqvarna CR125 Overview: In 2001, Husqvarna was having a bit of a moment in the US. After two decades off the AMA circuit, the all-new Fast By Ferracci team was set to bring the historic brand back to American motocross glory. With two-time AMA 125 Champion Steve Lamson and a team of young up-and-comers under the Ferracci tent, Husqvarna appeared ready to make a major splash in 2001.

While Husqvarna had all but disappeared from our shores after the sale of the original Swedish company to Cagiva in the late eighties, it had continued to thrive overseas. The new Italian Husqvarna developed a strong presence in the GPs with riders like Jackey Martens, Darryl King, Peter Johansson, and Alessio Chiodi piloting the machines to victory. Multiple World Motocross titles pointed to the competitiveness of the machines, but they remained more of a curiosity than a viable racing machine to most American riders in the 1990s.

With Husqvarna’s new push to get back into the US market the machines started to get a bit more attention in the press and at least two of the major magazines included the Husky in their shootouts for 2001. Both Dirt Bike and Dirt Rider included the Italian one-two-five in their rankings, but neither magazine saw fit to place it above the offerings from Austria or Japan. While the Husqvarna finished last in both comparisons, it was not without its virtues. Riders praised its high-quality components, impressive build quality, roomy layout, easy-to-ride power, and rock-solid stability. The suspension was also much improved for 2001 with a new Marzocchi fork and Sachs shock that performed better than the WP units found on the KTM.

Where things got tough for the Husqvarna was in its very European feel. When riding the Husky, it was clear that the bike was developed on different style tracks than we ride over here and that hurt it in the final rankings. The machine’s steering was very slow and its suspension was quite uncomfortable with big hits and sudden transitions. The motor was easy to ride but its shifting was notchy and it lacked the burst needed to clear tricky doubles out of tight turns. It was more of a momentum motor that was far happier flowing around fast Italian hillsides than going big out of turn one at A1. The machine was also the heaviest of the group and it felt that way on the track. In its native environment, the Husky was probably a solid performer, but to the US-based testers in 2001, there was a bit too much spaghetti in its recipe for their Western tastes.

2001 TM125 Cross Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – N/A Dirt Bike – N/A Dirt Rider – N/A Transworld MX – N/A Cycle News – 6th (out of 6) Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

2001 TM125 Cross Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – N/A Dirt Bike – N/A Dirt Rider – N/A Transworld MX – N/A Cycle News – 6th (out of 6) Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

A bike so exotic that it made the Husky look mainstream, the 2001 TM125 Cross offered impressive power and Italian verve to riders looking to buck the mainstream. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

A bike so exotic that it made the Husky look mainstream, the 2001 TM125 Cross offered impressive power and Italian verve to riders looking to buck the mainstream. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

2001 TM125 Cross Overview: In 2001, only one magazine saw fit to include Italy’s TM in their 125 shootout. Even more off the beaten path than the Husky, the other Italian was probably better known in the US for their rocket fast kart motors and gaudy pink plastic than their motocross performance. Despite their minuscule share of the US market, however, TM was building some of the trickest machines available in 2001. Their motor featured cooling jackets that extended into the lower cases to cool the intake charge as it entered the crankcase. The clutch was hydraulic, the engine cases looked “works,” the steel perimeter frame was unique, and the high-dollar Swedish Öhlins shock was premium. Everything from the billet brake pedal, to the Excel rims, to the tough Tecnosel graphics was premium in quality.

Like the Husky, however, the TM’s setup was more Matterley Basin than Muddy Creek. Well-known for making horsepower, the TM’s motor was extremely powerful but tricky to control. There was nothing down low, then an hard hit that rocketed the Italian Stallion forward. This worked well when you could keep up your momentum and row the gearbox but trying to play stop-and-go on a tight track left most riders frustrated. The plush Öhlins shock worked like a dream, but the grim Italian Paioli forks performed more like a nightmare. Harsh, jolting, and ultra-stiff, they made the KTM’s WP forks feel like a magic carpet by comparison. The Grimeca hydraulic clutch was trick, but its action was less liked than most of the traditional cable-actuated units from Japan. The TM’s handling was more precise than the Husky, but it remained more of a high desert hauler than a tight turn specialist. There was a pronounced understeer to the front end and the TM was far more comfortable railing the outside rather than trying to outduel the RM to the inside.

With its powerful motor, excellent shock, comfortable layout, and solid high-speed handling the TM125 Cross was a capable racer in the proper environment. It was faster than many of the other machines in the class but its light-switch power and cranky clutch made it difficult to master if the track was tight. The TM’s awful Paioli forks were probably the bike’s biggest downfall and finding someone to sort them out had to be the first item on any TM checklist. Once they were sorted, you were left with a wicked fast, super trick works bike for the masses. If you had the talent to make that work, then the Italian was your ticket to GP victories, but for most Americans, the TM was a bit too exotic to beat out the class’s more mainstream alternatives.