For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s revamped 1987 CR80R.

Photo Credit: Honda’s CR80R was the fire-breather of the class in 1986 and Big Red had even more heat on tap for 1987. Photo Credit: Honda

Photo Credit: Honda’s CR80R was the fire-breather of the class in 1986 and Big Red had even more heat on tap for 1987. Photo Credit: Honda

Today, the product cycle of the average mini-class machine is measured in decades rather than years. Unlike their larger counterparts, which typically get a major revamp every 4-5 years, minis are regularly expected to carry on with little more than Bold New Graphics for an extraordinary amount of time. It is the only division still dominated by two-strokes and the one asked to accommodate the most varied spectrum of talent and size. The economics of mini-class racing just don’t support the relentless march of technology that has been the hallmark of modern motocross development.

Photo Credit: Honda’s first CR80R made its debut in 1980 to much fanfare. The smallest Elsinore packed tons of punch but its chassis was not up to running with the class leaders. Photo Credit: Honda

Photo Credit: Honda’s first CR80R made its debut in 1980 to much fanfare. The smallest Elsinore packed tons of punch but its chassis was not up to running with the class leaders. Photo Credit: Honda

In the 1980s, however, the landscape of mini-class development was very different. The advances made in the 80 class were moving hand-in-hand with the strides being made by their big bike cousins. Technological advances like linkage suspension, water-cooling, disc brakes, and variable exhaust ports were making their debut, and in many cases, the minis were getting them at the same pace as their bigger brothers. Today’s RM85 is little changed from the machine that Eli Tomac raced in the early 2000s, but in the 1980s, if you were on a two-year-old mini, there was a good chance you were bringing a knife to a gunfight.

In 1986, Honda finally broke Kawasaki’s stranglehold on the mini division with a rocket-fast CR80R. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1986, Honda finally broke Kawasaki’s stranglehold on the mini division with a rocket-fast CR80R. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the case of Honda’s CR80R, it started life as an overpowered and under-suspended also-ran of a machine. Initially introduced for the 1980 season, Honda’s first two-stroke mini pumped out tons of thrust from its fire engine red motor but its flimsy frame and underdamped suspension held it back from being a contender.

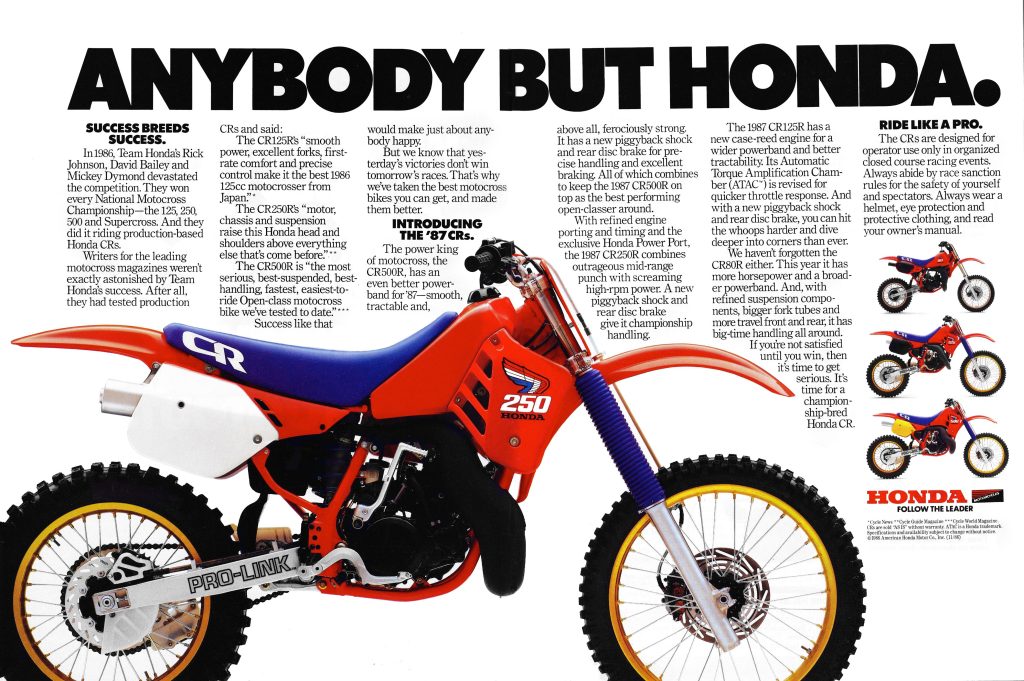

Honda’s 1986 motocross lineup was one of the most dominant in the history of the sport. Every machine from the pint-sized CR80R to the ground-pounding CR500R had the competition seeing red in ’86. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda’s 1986 motocross lineup was one of the most dominant in the history of the sport. Every machine from the pint-sized CR80R to the ground-pounding CR500R had the competition seeing red in ’86. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda quickly ramped up development on their smallest CR, adding a scaled-down version of their Pro-Link single-shock suspension in 1982 and liquid cooling in 1983. Suspension travel increased quickly in this era with the 1980 CR’s 30mm forks and 6.7 inches of travel growing to a beefy 33mm and 8.9 inches of movement by 1983. During this time, the CR80R became more competitive, adding Honda’s version of a “power valve,” the ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) in 1984 in yet another complete redesign of the red minicrosser. One year later, the CR80R was once again completely revamped with all-new bodywork, longer travel suspension, and a redesigned chassis. This marked the fourth complete redesign of Honda’s mini in as many years. The ATAC remained, but virtually everything else was all-new.

As impressive as the ’86 Hondas were, Big Red had even more firepower on tap for 1987. All four of the CRs received significant updates with the ’87 versions of the red machines proving even more dominant than the year before. Photo Credit: Honda

As impressive as the ’86 Hondas were, Big Red had even more firepower on tap for 1987. All four of the CRs received significant updates with the ’87 versions of the red machines proving even more dominant than the year before. Photo Credit: Honda

Unfortunately, despite all of this rapid development, Honda’s smallest racer failed to capture the coveted top spot in the mini-class standings. The CR was competitive, but it never captured the devotion of Kawasaki’s powerhouse KX80. From 1982 through 1985, Kawasaki’s little green ripper was the unanimous choice as the best mini-class racer available. The KX80’s suspension was not as supple as the RM80, and it failed to handle with the finesse of the CR80R, but its overwhelming horsepower advantage gave it an unbeatable edge in a class dominated by motor performance.

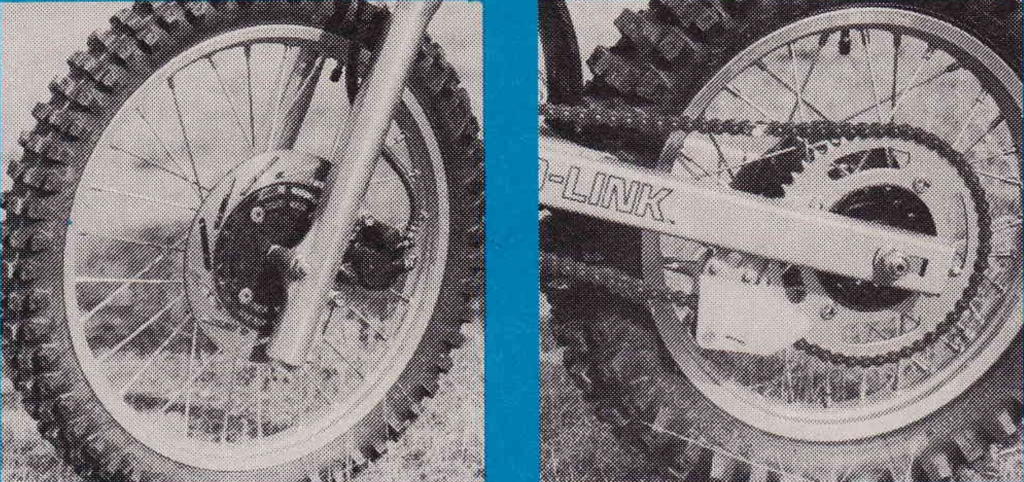

An all-new front end for 1987 included beefed-up clamps, 2mm larger fork tubes, and a 0.6-inch increase in suspension travel. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new front end for 1987 included beefed-up clamps, 2mm larger fork tubes, and a 0.6-inch increase in suspension travel. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1986, Honda finally broke Kawasaki’s stranglehold on the mini division by introducing an all-new motor that propelled the CR to the top of the top of the 80cc horsepower hierarchy. Visually, the ’86 CR80R looked nearly identical to the ’85 version, but on the track, the Honda was a very different machine. The heart of this transformation was the CR’s all-new 83cc power plant which deleted the ’84 and ’85 model’s ATAC exhaust device in favor of a much simpler design. Kawasaki’s KIPS (Kawasaki Integrated Power-valve System) would eventually prove the worth of exhaust resonance chambers like the ATAC when used in conjunction with a variable exhaust valve like the YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System), but its effectiveness as a stand-alone system was far less conclusive. By deleting the ATAC, Honda was able to lower costs, simplify maintenance, a provide a less encumbered exhaust design. The all-new cylinder also featured Honda’s first production application of Mahle’s “Nikasil” nickel silicon-carbide cylinder coating. In use on their works racers for several years, Nikasil was prized for its extreme hardness, reduced friction, superior oil retention, and improved heat transfer properties. It was also lighter than a traditional iron cylinder liner. These improvements allowed Honda to run tighter tolerances and higher compression in the top end without fear of heat or friction-related failures. In addition to the new motor, the ’86 CR80R featured subtle changes to the riding compartment to provide more room for larger riders, increased strength in the frame, a larger and stronger swingarm, upgraded wheels, a larger airbox, a new front disc brake, and updated graphics.

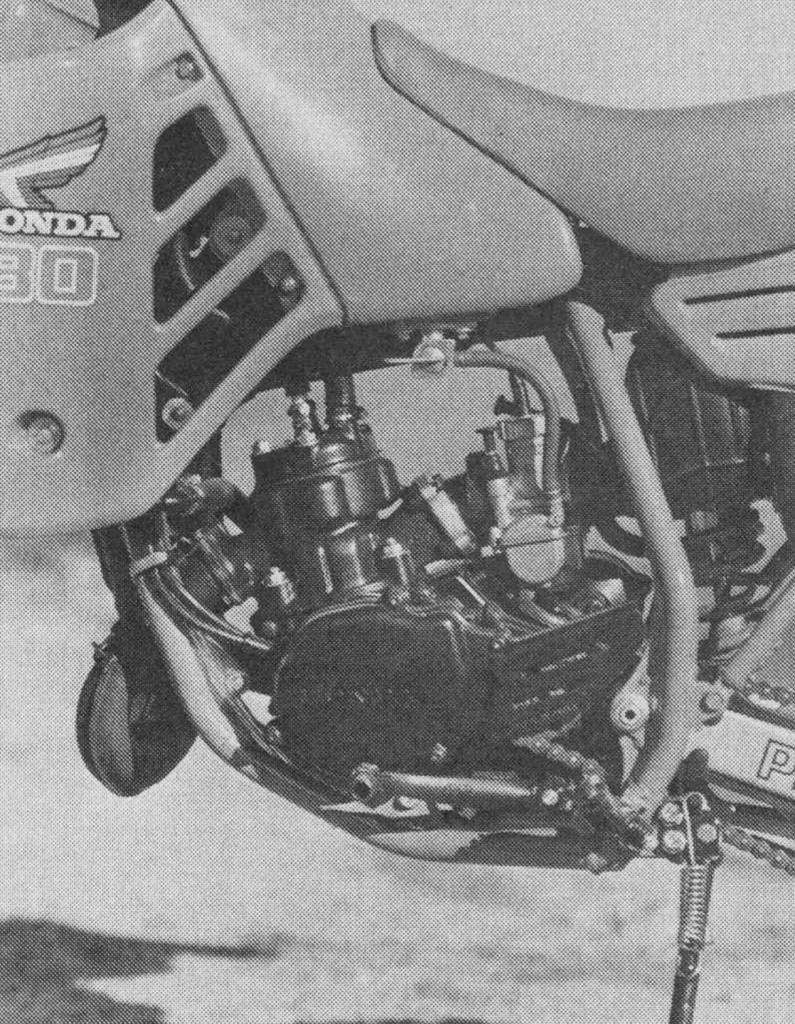

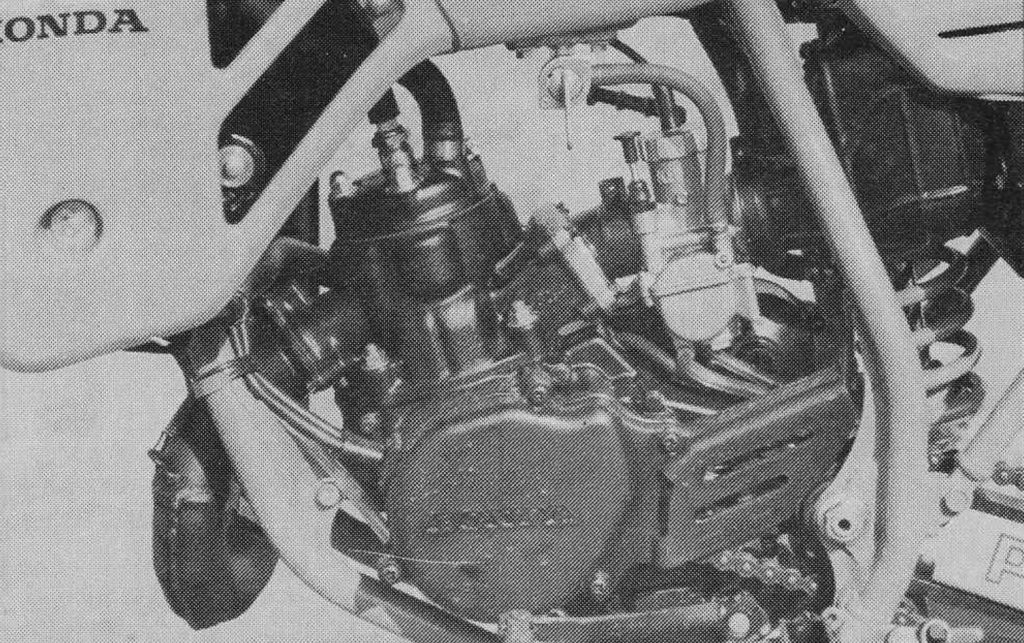

In 1986, Honda moved to an all-new motor design that deleted the ATAC “power valve” employed on the ’84 and ’85 CR80R. The new engine was lighter, easier to service, and far more powerful than the old design. Photo Credit: MOTOCross

In 1986, Honda moved to an all-new motor design that deleted the ATAC “power valve” employed on the ’84 and ’85 CR80R. The new engine was lighter, easier to service, and far more powerful than the old design. Photo Credit: MOTOCross

On the track, the ’86 CR80R proved to be by far the best mini-class racer Honda had ever offered. Its power was incredibly broad, with tons of snap off the line, a massive hit in the middle, and just enough on top to keep the competition sucking its vapor trail. Its clutch action and shifting were the best in the class and the motor was both incredibly fast and easy to ride. Fast guys loved its blistering acceleration and many felt the CR was faster than some of the competition’s 125s. It was an absolute rocket that demanded respect, and this did make it a handful at times for less experienced riders. Smaller and slower riders were probably a better fit on Yamaha’s more novice-friendly YZ80. As before, its suspension action was less stellar than Suzuki’s RM80, but for most serious racers, the CR80R was the ultimate mini-class machine in 1986.

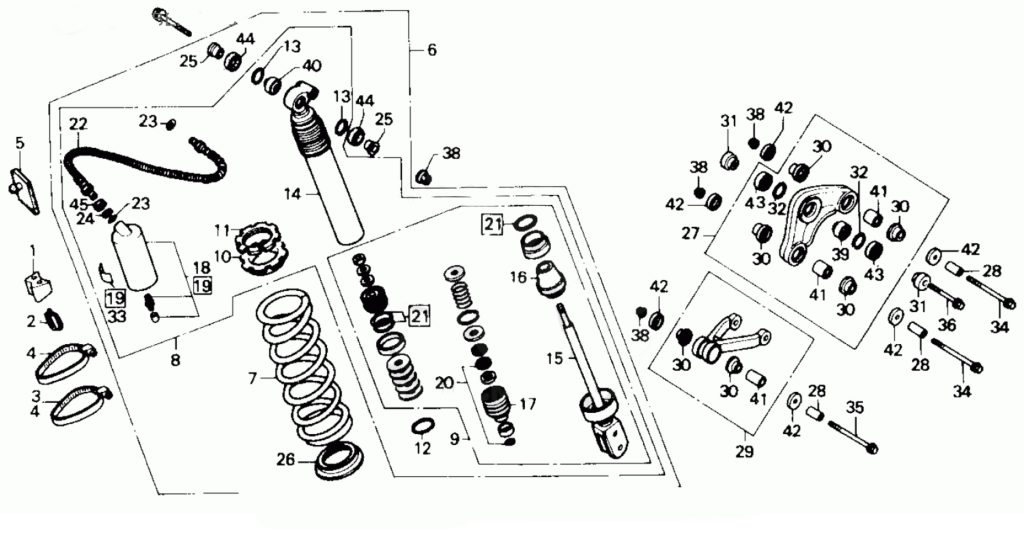

An all-new shock for 1987 added a “Bilstein type” damping system, a revamped leverage ratio for the Pro-Link, and an additional 0.4-inches of travel. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new shock for 1987 added a “Bilstein type” damping system, a revamped leverage ratio for the Pro-Link, and an additional 0.4-inches of travel. Photo Credit: Honda

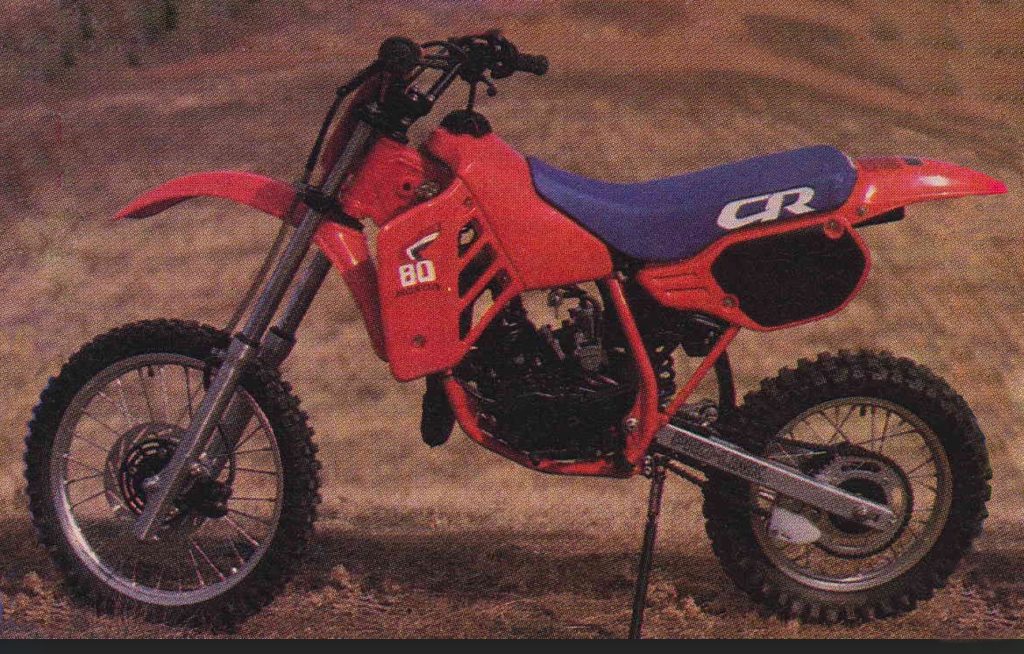

After wresting the mini class laurels from Kawasaki in 1986, Honda was determined to keep the 80cc division seeing red in 1987. Once again, visual changes were minimal, with updated graphics being the most prominent update for ’87. All of the bodywork was a carryover, with the same Flash Red and blue color scheme Honda had been featuring on their motocross machines since 1983. Chassis changes for 1987 centered around the updated suspension which offered slightly more travel, improved damping, and increased rigidity. All-new forks improved handling by increasing the diameter of the tubes from 33mm to 35mm and by adding 0.6 inches of travel. New clamps offered increased rigidity and repositioned the forks 2.0mm farther apart for an improved steering feel. Internally, the Showa forks featured all-new settings, but they lacked the more sophisticated cartridge damping system and external adjustability found on the CR’s larger siblings.

Motor changes for 1987 included revamped porting, a reshaped head, freer-flowing reeds, a remapped ignition, a redesigned piston, and a retuned exhaust. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Motor changes for 1987 included revamped porting, a reshaped head, freer-flowing reeds, a remapped ignition, a redesigned piston, and a retuned exhaust. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the rear, an all-new Showa shock added a Bilstein-style damping system that separated the damping chores into two separate valving stacks. This new “dedicated function” setup passed fluid through one set of washers on the compression stroke and a separate stack on the rebound. The new shock delivered 0.4 inches more travel than in 1986 and featured external adjustments for compression and rebound control. Bolted to the revamped shock was a Pro-Link linkage that was redesigned to provide a more progressive action and less bottoming for 1987. Frame changes for ’87 were minimal, with most being aimed at fine-tuning the geometry to match the new longer-travel suspension. Honda felt the smallest CR was already the best-handling machine in the class and the aim was to maintain that advantage rather than change any of the machine’s basic handling traits.

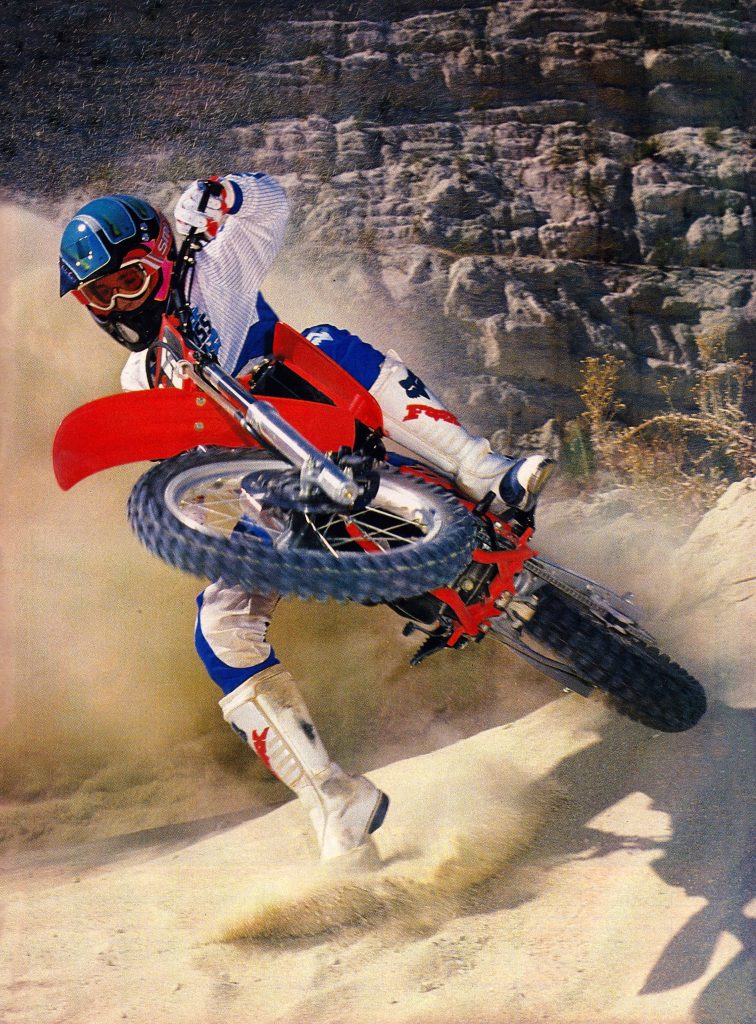

Power is the name of the game in the mini division and Honda had the firepower to take skilled riders to the front in 1987. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Power is the name of the game in the mini division and Honda had the firepower to take skilled riders to the front in 1987. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the motor front, Honda looked to build on the ’86 machine’s momentum by boosting top-end power and improving reliability. In 1986, one of the CR80R’s few weak spots was the motor’s durability. The new single-ring piston Honda transitioned to tended to wear out very quickly and the motor’s performance noticeably suffered if its maintenance was neglected. Clutch life was also disappointingly short with the stock components in place. The action was buttery smooth, but the stock springs and aluminum drive plates had a hard time holding up under the abuse the little motor’s prodigious power output delivered.

The mini class of 1987 offered a broad assortment of chassis sizes and performance levels to accommodate the wide range of aspiring racers found in the 80 class. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The mini class of 1987 offered a broad assortment of chassis sizes and performance levels to accommodate the wide range of aspiring racers found in the 80 class. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

To boost durability and performance, Honda made several upgrades to the CR80R’s clutch in 1987. First up was an all-new assembly that moved from aluminum to steel for the CR’s drive plates. This increased longevity and added a bit of additional inertia to the Honda’s drivetrain. All-new fiber plates for 1987 offered additional grooving for improved oil flow and new stiffer springs provided a more positive engagement. Changes to the lower cases also allowed the CR to carry an additional 50cc of gear oil to keep everything in the bottom end cooled and lubricated. Aside from the additional oil capacity, the CR’s excellent close-ratio six-speed transmission was unchanged for 1987.

In 1987, nothing in the 80 class had the CR’s combination of broad power and blistering performance. Faster than some 125s, and blessed with a flawless transmission and clutch, the CR’s 83cc powerhouse of an engine was the ultimate in mini-class performance. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1987, nothing in the 80 class had the CR’s combination of broad power and blistering performance. Faster than some 125s, and blessed with a flawless transmission and clutch, the CR’s 83cc powerhouse of an engine was the ultimate in mini-class performance. Photo Credit: Honda

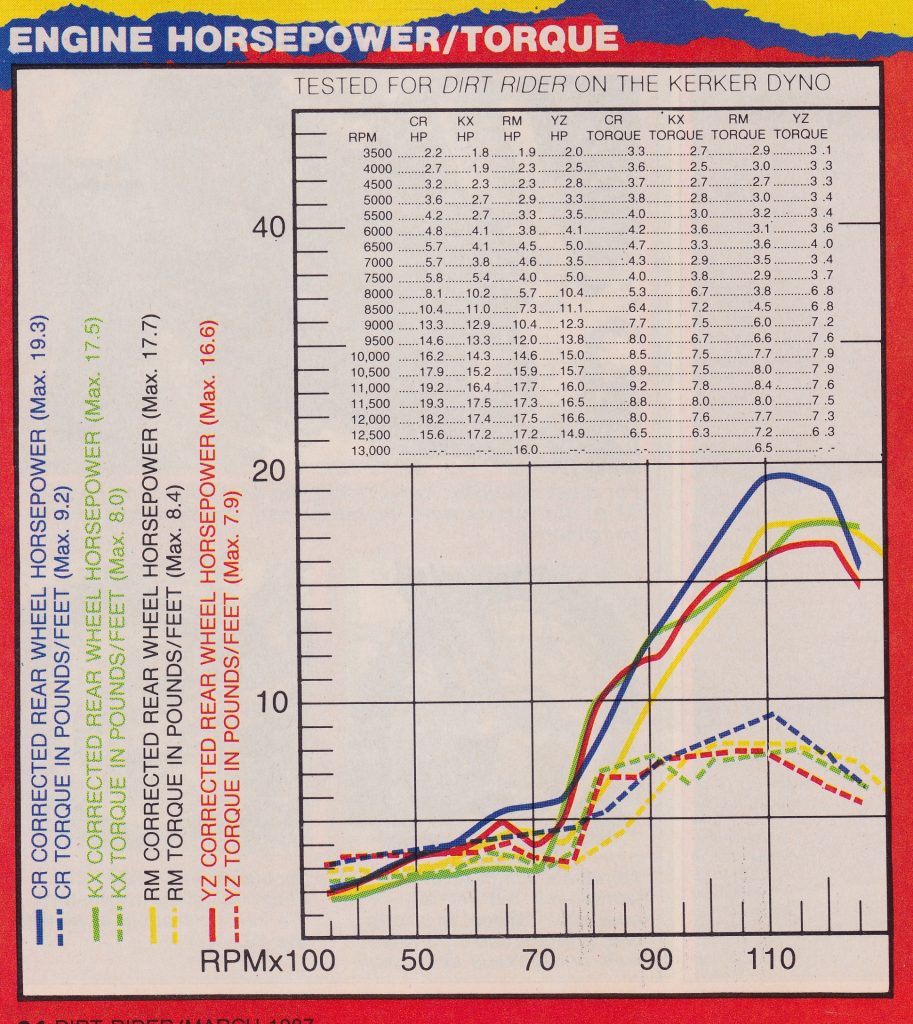

The top end of the motor was updated as well with all-new porting, a reshaped head, a redesigned piston, and an enlarged intake with reeds that opened wider for increased flow. The piston remained a single-ring design but the ’87 version offered improved sealing and increased durability. The new head lowered compression slightly with the ’87 version coming in at 8.1-to-1 compared to the ’86 CR’s 8.4-to-1. An all-new expansion chamber featured a reshaped profile designed to provide a stronger pull on top and a retimed ignition looked to fill in any dips in the Honda’s powerband. All told, these changes added up to a whopping 19.3 horsepower on Dirt Rider’s dyno. This was one horsepower more than the 1986 CR80R and nearly 2 horsepower more than any of the Honda’s 80cc competitors.

Kerker’s dyno told the tale of Honda’s motor dominance in 1987. The CR out-torqued its rivals down low and ripped past them to the tune of nearly 2 horsepower on top. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Kerker’s dyno told the tale of Honda’s motor dominance in 1987. The CR out-torqued its rivals down low and ripped past them to the tune of nearly 2 horsepower on top. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the track, this power advantage was immediately apparent with the little Honda once again laying waste to its competitors in any contest of speed. Low-end power was strong for a mini of the time with the CR pulling hard from the first crack of the throttle. The midrange power was just as explosive as the year before with tons of hit and white-knuckle acceleration. Top-end power was stronger than in 1986 with the CR pulling harder and longer. For experienced riders, it was the perfect power band; broad, flexible, and incredibly fast. It was still a bit too aggressive for less experienced pilots but for anyone aspiring to victory, the CR offered the ultimate motor of doom in 1987.

The CR’s all-new 35mm front forks offered reduced flex and improved damping over the year before. Faster and heavier riders would have benefited from heavier springs, but they worked well for most riders in the CR’s target demo. Photo Credit: Honda

The CR’s all-new 35mm front forks offered reduced flex and improved damping over the year before. Faster and heavier riders would have benefited from heavier springs, but they worked well for most riders in the CR’s target demo. Photo Credit: Honda

Despite using bodywork that dated back to 1985, the CR remained one of the best-looking machines in its class. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

Despite using bodywork that dated back to 1985, the CR remained one of the best-looking machines in its class. Photo Credit: Karel Kramer

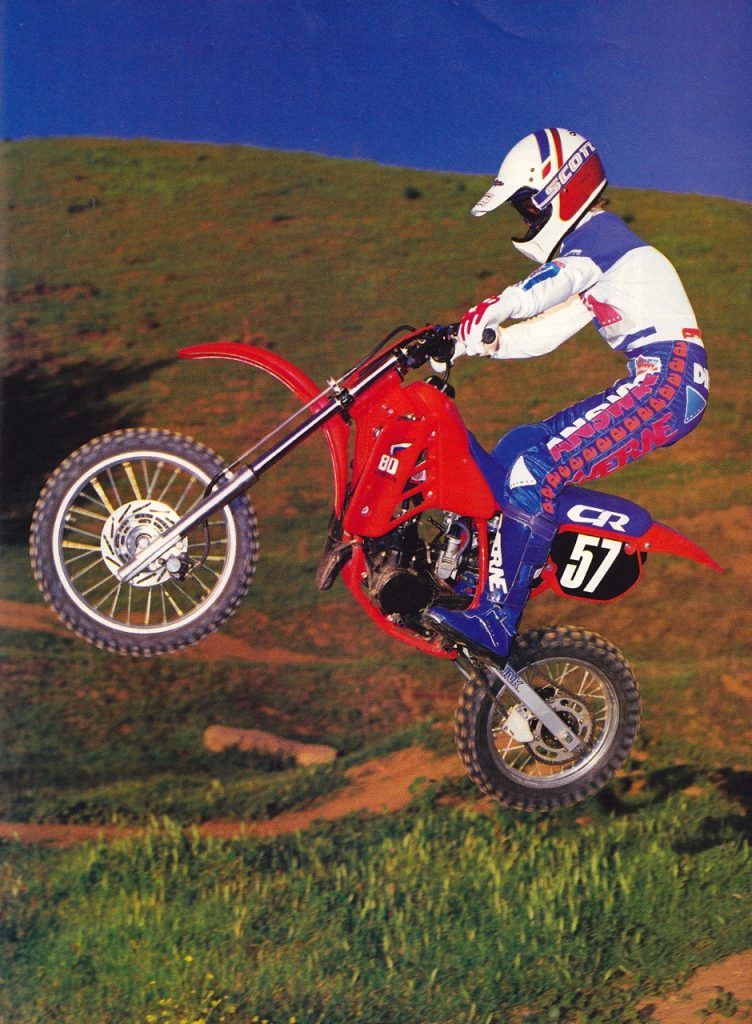

On the chassis front, the CR was considered an excellent handler in 1987. Today, the bike would feel tiny, but in 1987, the Honda offered a mid-sized package that was roomier than the Yamaha but less spacious than the larger Kawasaki and Suzuki minis. This made it a good fit for a wide variety of kids. Overall handling was very aggressive with the CR offering the tightest and most sure-footed turning in the class. Like its larger brothers, the CR craved the inside line and could carve under all of its mini competition with relative ease. The new larger 35mm forks and stronger clamps addressed the flex faster riders had complained about in 1986 and the Honda felt far more precise when pushed. Aerial manners were superb, but care had to be taken not to grab a bit too much boost on takeoff. With its massive hit and short wheelbase, it was very easy to loop out the Honda, a fact less experienced riders quickly discovered. High-speed stability was never one of the CR80R’s strong suits and the ’87 version continued this trend. The machine’s aggressive geometry meant the Honda could be a bit twitchy at speed, but it was far less of a Tilt-A-Whirl than its big brothers. It was not as rock solid at speed as the KX and RM, but it was stable enough to not terrify Junior and generally did not break out into violent fits of headshake like the full-sized CRs.

Goldilocks: With its midsized chassis the CR slotted in between the diminutive YZ and more spacious KX and RM. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Goldilocks: With its midsized chassis the CR slotted in between the diminutive YZ and more spacious KX and RM. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The other half of the Honda’s handling equation was its new suspension. In 1987, half the class was still using 33mm forks (YZ and RM) while the other half had moved on to the beefier 35mm tubes (KX and CR). While this did give the Honda and Kawasaki an advantage in handling accuracy under heavy loads and on hard impacts, it did not guarantee the best overall damping performance. In this case, that award went to the RM80 and its “old school” 33mm Kayaba forks which delivered the smoothest damping and best overall performance in the class. Fast guys still noticed a fair amount of flex in the front end but nothing in the class was as plush and well-controlled as the forks found on the RM in 1987.

When fresh, the CR’s new Showa shock delivered a well-controlled ride in most conditions. Unfortunately, its performance deteriorated quickly if you neglected to have it serviced regularly. Photo Credit: Honda

When fresh, the CR’s new Showa shock delivered a well-controlled ride in most conditions. Unfortunately, its performance deteriorated quickly if you neglected to have it serviced regularly. Photo Credit: Honda

While the RM was a standout, the Honda’s new 35mm Showas were far from a disappointment. Overall damping control was very good, and the stock spring rate worked well for anyone short of a pint-sized Rick Johnson. In the rear, the new Pro-Link delivered a well-controlled ride that allowed riders to attack the track. The adjustable compression and rebound settings permitted the rear end of the CR to be dialed in for a wide variety of riders but testers did note that the damping performance of the CR’s shock seemed to deteriorate quickly with use. As with the forks, the shock was a bit softly sprung and underdamped for bigger and faster riders but most pilots within the CR’s target demo were likely to be happy with the stock suspension.

With its explosive power delivery, the CR could prove to be quite a handful for inexperienced riders. The Honda liked to loft its front end out of every turn and grabbing a bit too much throttle on takeoff was a sure-fire recipe for a loop out. Phot Credit: Motocross Action

With its explosive power delivery, the CR could prove to be quite a handful for inexperienced riders. The Honda liked to loft its front end out of every turn and grabbing a bit too much throttle on takeoff was a sure-fire recipe for a loop out. Phot Credit: Motocross Action

On the detailing front, the 1987 CR80R was a mix of typical Honda excellence with a few un-Honda-like disappointments. On the plus side were the excellent shifting, flawless clutch, perfectly fitting bodywork, fully removable subframe, high-quality fasteners, comfortable controls, excellent ergonomics, crisp jetting, and matinee idol looks. There was no power valve to mess with and the new clutch was much more durable than the overworked ’86 version. In 1987, nothing looked, fit, or felt as refined as a Honda.

In 1987, the RM was the best suspended, the CR was the fastest, the Yamaha was the best for beginners, and the Kawasaki was the best machine for larger kids trying to squeeze out one more year on the minis. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1987, the RM was the best suspended, the CR was the fastest, the Yamaha was the best for beginners, and the Kawasaki was the best machine for larger kids trying to squeeze out one more year on the minis. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the flip side of that coin were the CR’s lackluster brakes and disappointing reliability. At the time, these were categories typically dominated by Honda, so their inclusion in the CR’s faults was doubly disappointing. Neither of the CR’s brakes was very impressive with the front being most notable for its mushy feel. The rear drum got the job done, but by 1987, Kawasaki had already moved on to a much more powerful disc for the rear of the KX80. Adding insult to injury was the fact that some CRs were reportedly produced with improperly manufactured brake shoes leading to broken shoes and destroyed rear hubs. Ugh…

Typically a Honda strength, the disc/drum combination found on the CR80R in 1987 was surprisingly mediocre. Most testers blamed the Honda’s flexy plastic brake line for delivering its mushy feel and lackluster power. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Typically a Honda strength, the disc/drum combination found on the CR80R in 1987 was surprisingly mediocre. Most testers blamed the Honda’s flexy plastic brake line for delivering its mushy feel and lackluster power. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Up front, the CR’s braking performance was mainly hampered by the flexy plastic line Honda spec’d for the machine. It delivered a spongy feel at the lever that detracted from an otherwise excellent system. The disappointing front disc and mediocre drum in the rear were not a great combination to have to slow down the fastest bike in the class. If you replaced the front line with a braided steel alternative then the braking feel improved greatly, but in stock condition, the CR’s front and rear braking performance was disappointing.

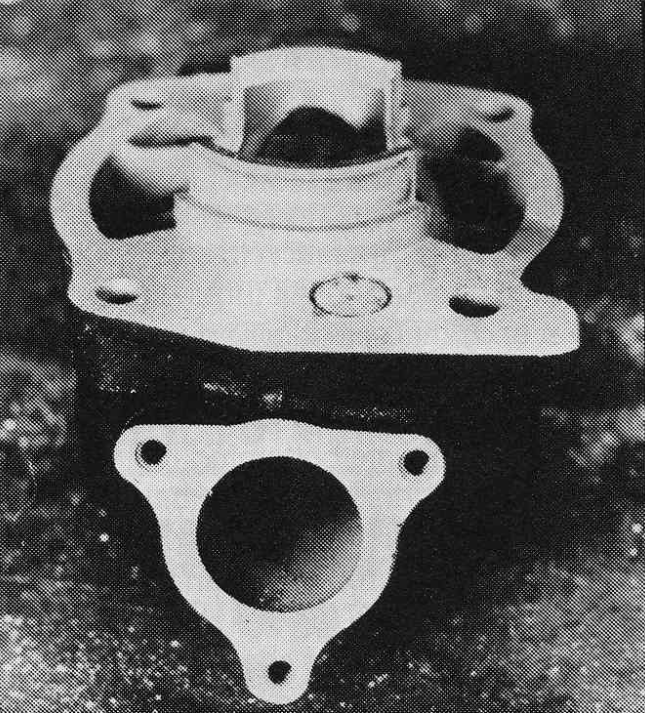

Some CR cylinders in 1987 suffered from machining issues and it was advisable to have your cylinder inspected and the ports chamfered before hitting the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Some CR cylinders in 1987 suffered from machining issues and it was advisable to have your cylinder inspected and the ports chamfered before hitting the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In addition to the unsatisfactory brakes, the Honda’s motor proved to be disappointingly fragile. The CR’s plated cylinder could not be bored if damaged and the single-ring piston continued to wear out exceedingly quickly. If ignored, the Honda’s performance deteriorated quickly and more than a few (including magazine test units) were known to grenade for no apparent reason. Improperly chamfered ports at the factory may have been the culprit and it was advisable to have your CR’s cylinder looked at by a knowledgeable tuner before taking it to the track. Once the cylinder was cleaned up, the CR’s motor was largely trouble-free as long as it was torn down and inspected regularly. If you kept the air filter clean, ran good quality oil, and religiously serviced the top-end, the Honda was a decently reliable machine.

Blazing fast, excellent handling, well suspended, and beautiful to behold, the CR80R was the machine of choice for aspiring mini pros in 1987. Photo Credit: Honda

Blazing fast, excellent handling, well suspended, and beautiful to behold, the CR80R was the machine of choice for aspiring mini pros in 1987. Photo Credit: Honda

In the end, the 1987 CR80R turned out to be an expert-level machine that demanded an expert level of care. An absolute rocket of a bike, it was faster than some 125s and too much machine for some mini pilots. For them, the white, yellow, or green machines may have been a better choice, but if you were looking to ride the fastest, nastiest, and gnarliest mini around, then going red was the obvious choice in 1987.