For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Yamaha’s pretty in pink YZ125 for 1992.

After a substantial redesign in 1991, Yamaha’s YZ125 was back for 1992 with a modest list of updates aimed at improving its back-of-the-pack standing. Photo Credit: Yamaha

After a substantial redesign in 1991, Yamaha’s YZ125 was back for 1992 with a modest list of updates aimed at improving its back-of-the-pack standing. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The early 1990s were a tough time to be riding a Yamaha in the 125 class. While the YZ250 was considered one of the best machines available, the stock YZ125 was more often the butt of jokes than the winner of laurels on the track. Once a punchy and competitive powerplant, its 124cc case-reed mill was beginning to show its age by the turn of the decade. All-new in 1986, the YZ125’s motor was a huge improvement over the motor it replaced, delivering a strong blast of power that rocketed the YZ from corner to corner. Its powerband was short, but the Yamaha was fast and fun to ride.

Originally introduced in 1986, Yamaha’s 124 case-reed mill started as a punchy and fun-to-ride alternative to the top-end screamers offered by Honda, Suzuki, and Kawasaki. By the early nineties, however, its one-dimensional power delivery and modest overall output were no longer capable of keeping up with the newer and more versatile motors offered by the competition. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Originally introduced in 1986, Yamaha’s 124 case-reed mill started as a punchy and fun-to-ride alternative to the top-end screamers offered by Honda, Suzuki, and Kawasaki. By the early nineties, however, its one-dimensional power delivery and modest overall output were no longer capable of keeping up with the newer and more versatile motors offered by the competition. Photo Credit: Yamaha

By 1991, however, the YZ’s engine was no longer considered competitive with its rivals. Its power valve system dated back to 1982 and it no longer offered the firepower to run with rockets like Honda’s CR125R. On the dyno, the YZ’s motor looked impressive with a very strong 30 horsepower on tap, but those ponies were far less impressive on the track. On hard soil, the YZ pulled reasonably well but once the track was ripped deep, the Yamaha struggled. There was not a lot of pull down low nor on top and its previously impressive midrange was no longer up to snuff against snappy rivals like Suzuki’s RM125. Add in a stubborn transmission and a propensity to sputter in the rough and bog on jump landings and you had the recipe for a resounding last-place finish in the 1991 125 standings.

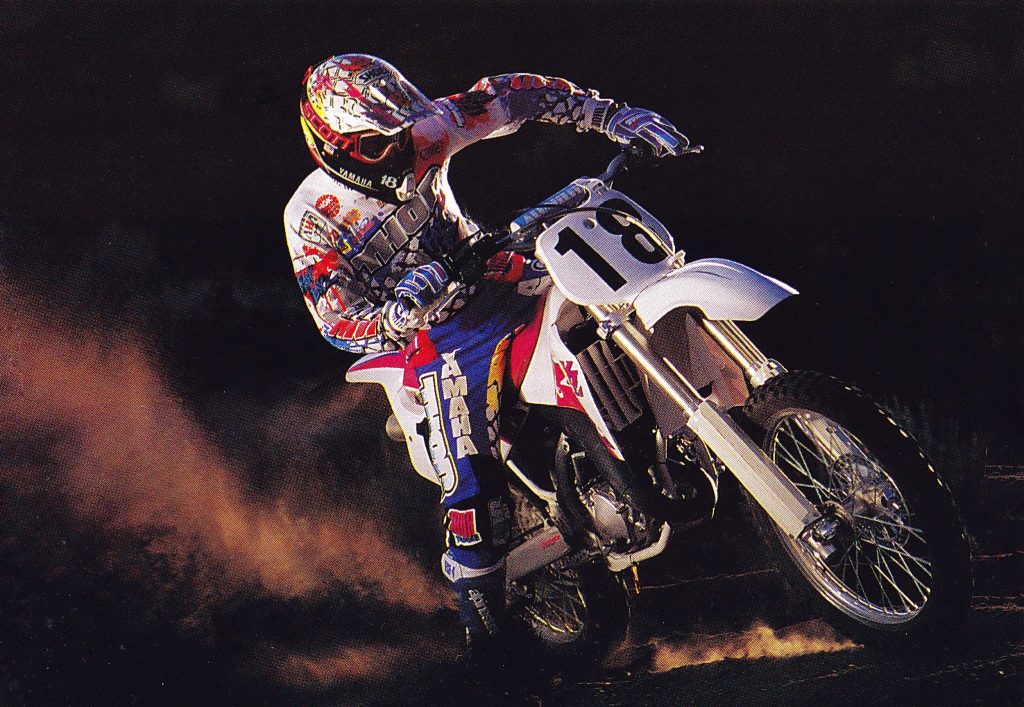

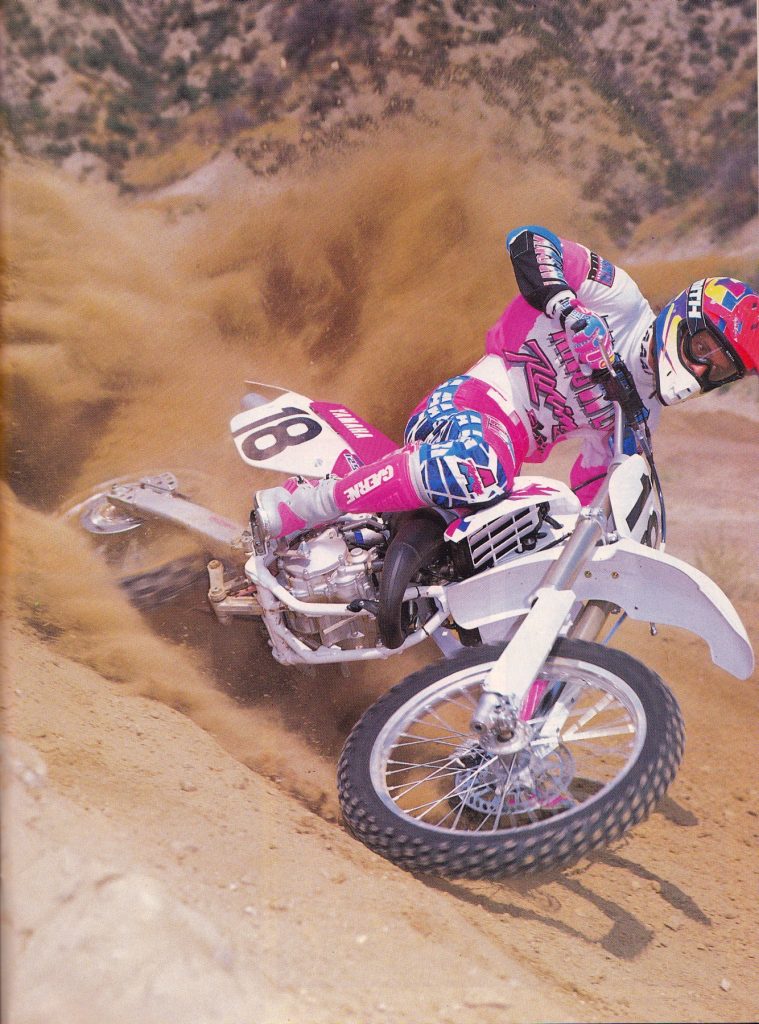

In 1992, Yamaha’s top gun in the 125 class was Jeff Emig. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1992, Yamaha’s top gun in the 125 class was Jeff Emig. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While the motor proved to be a massive disappointment, the rest of the 1991 YZ125 was a solid improvement over the 1990 machine. The new “magenta” color scheme and redesigned rear bodywork freshened up the Why-Zed’s looks and the revamped chassis offered excellent stability and good turning. Suspension action was middle of the pack, but the bike was comfortable, and novices liked its unintimidating power. Overall, it was a good machine in need of a serious power upgrade.

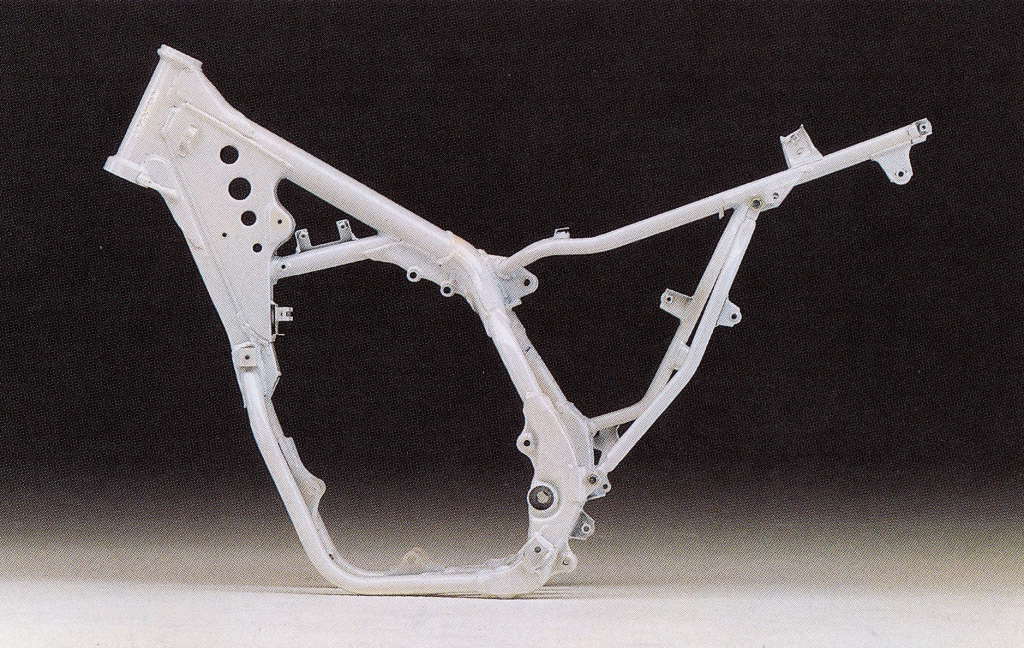

The YZ125’s frame for 1992 was largely a carryover from the year before with the only significant change being a new triple clamp that offered increased strength and a repositioning of the forks to be 5mm farther apart. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The YZ125’s frame for 1992 was largely a carryover from the year before with the only significant change being a new triple clamp that offered increased strength and a repositioning of the forks to be 5mm farther apart. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While the YZ clearly could have used an all-new motor, that was not in the cards for 1992. Instead, Yamaha once again tried to massage, tweak, and squeeze a few extra ponies out of their slightly geriatric mill. First up was an all-new top end with revised porting that Yamaha hoped would boost mid-range performance. Both the transfer and exhaust ports were reshaped, and the head was reconfigured from a dome to a flat configuration. The original rotating drum power valve remained but Yamaha reshaped its profile and reduced the diameter of the drum by 3mm to reduce heat-related deformation. An all-new ignition added digital control and increased capacity for a fatter spark and more precise control. The new ignition featured a revised profile to increase low-end response and boost top-end pull. Internally, the seams of the exhaust pipe were smoothed to provide improved flow. The carburetor remained a Mikuni 35mm TMX flat-slide and despite many people blaming the ’91 YZ’s sputtering issues on the reeds, they remained unchanged for 1992. The Yamaha’s notoriously stubborn six-speed transmission remained unchanged but a new clutch mechanism reduced effort and improved feel by redesigning the actuation arm and reducing the number of teeth on the pinion gear from 12 to 11.

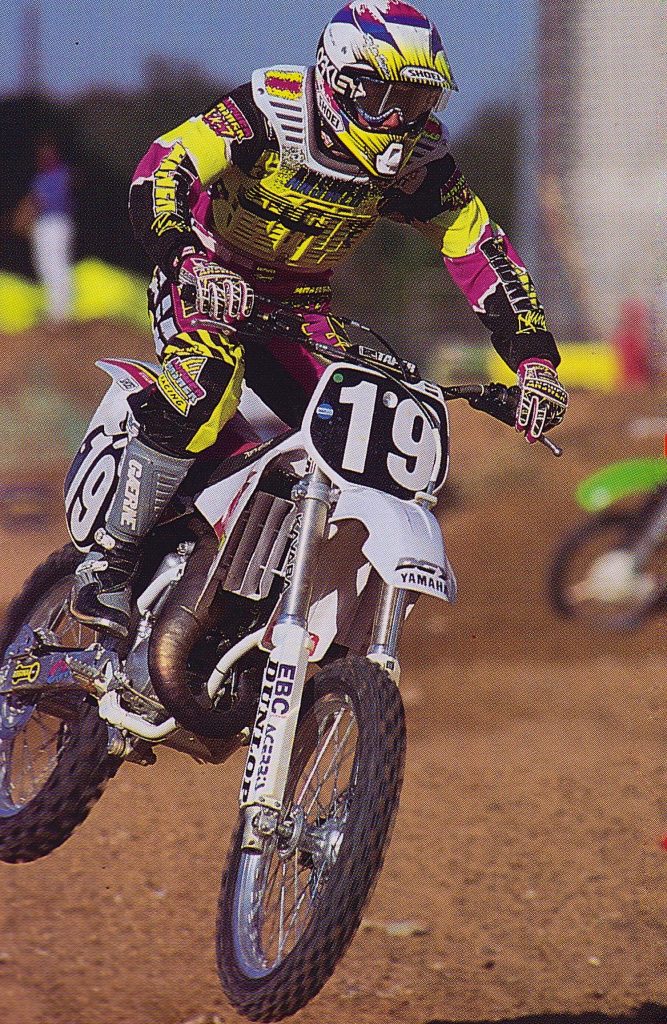

In addition to Jeff Emig, Yamaha’s 125 lineup included Doug Henry (pictured) and Jimmy Button on DGY-backed YZ125s. Photo credit: Jeff Ames

In addition to Jeff Emig, Yamaha’s 125 lineup included Doug Henry (pictured) and Jimmy Button on DGY-backed YZ125s. Photo credit: Jeff Ames

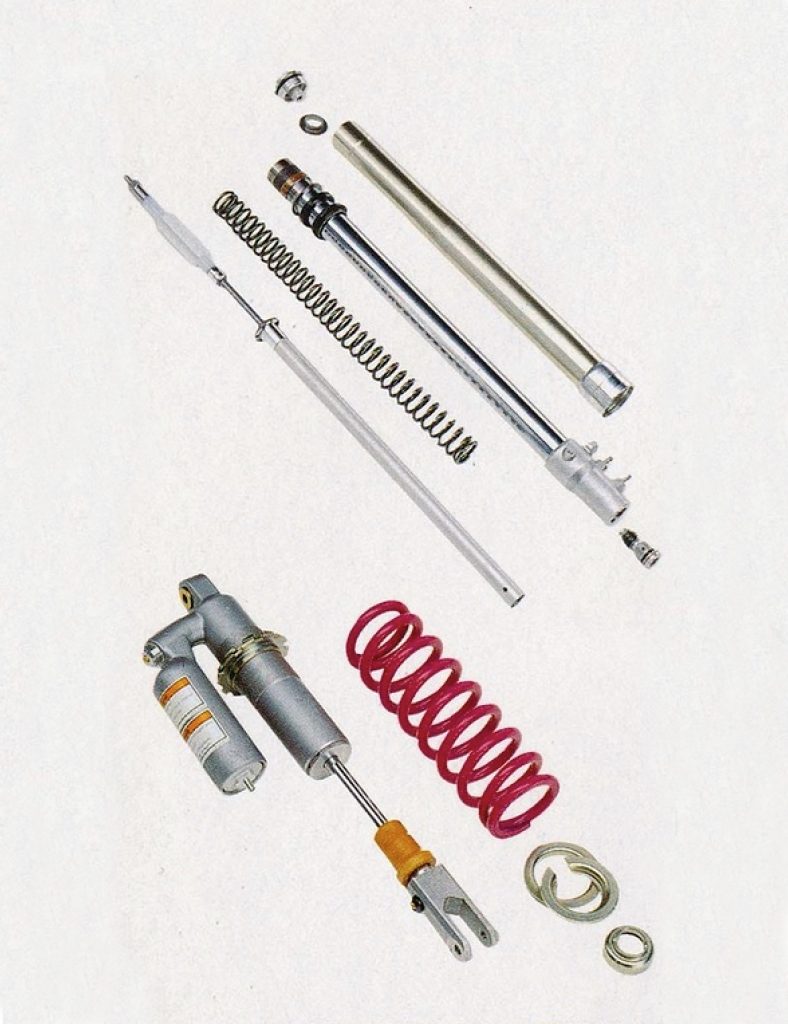

All-new suspension for 1992 included redesigned KYB cartridge forks with new internal damping and increased travel and a revamped Kayaba shock that featured a new valving system designed to reduce heat-related fade. Photo Credit: Yamaha

All-new suspension for 1992 included redesigned KYB cartridge forks with new internal damping and increased travel and a revamped Kayaba shock that featured a new valving system designed to reduce heat-related fade. Photo Credit: Yamaha

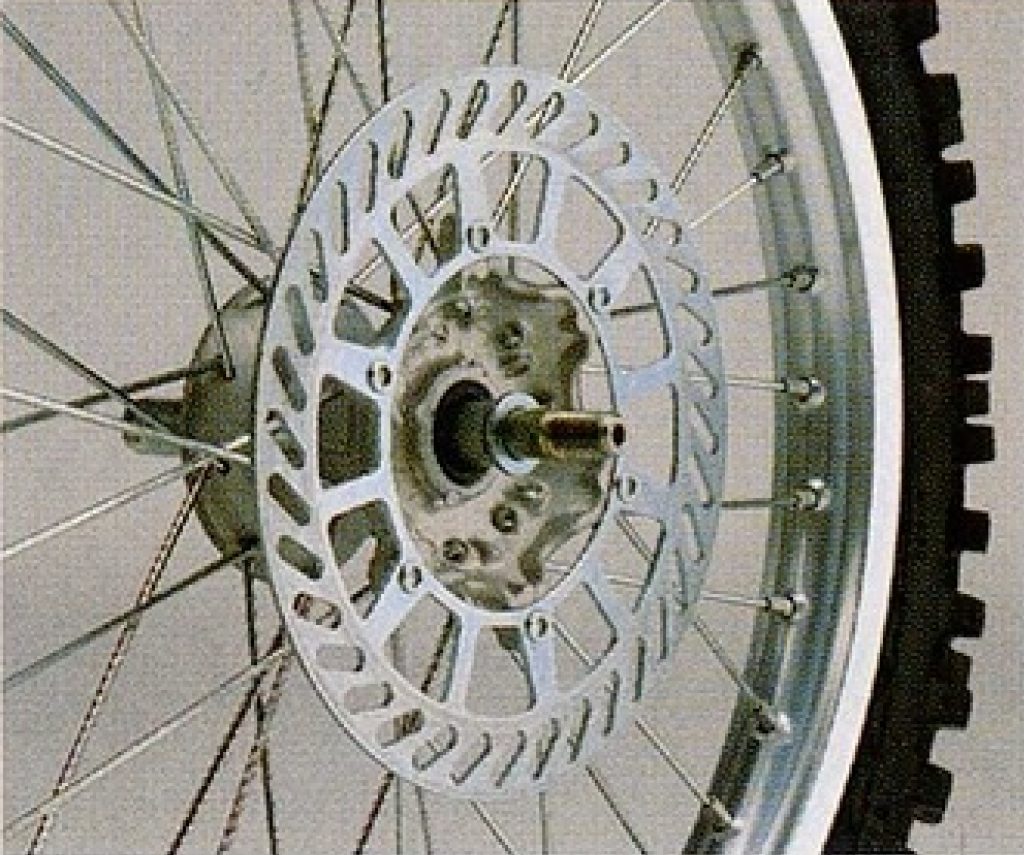

On the suspension front, the YZ featured all-new cartridge forks and a revised shock for improved performance. The Kayaba forks remained 43mm in diameter but featured new internals and an additional 10mm of travel. Overall travel was set at 12.2 inches with external adjustments available for compression and rebound damping. A redesigned clamp was added that increased strength and repositioned the forks 5mm farther apart for improved steering precision. To further increase front-end rigidity the diameter of the front axle increased from 15mm to 17mm as well.

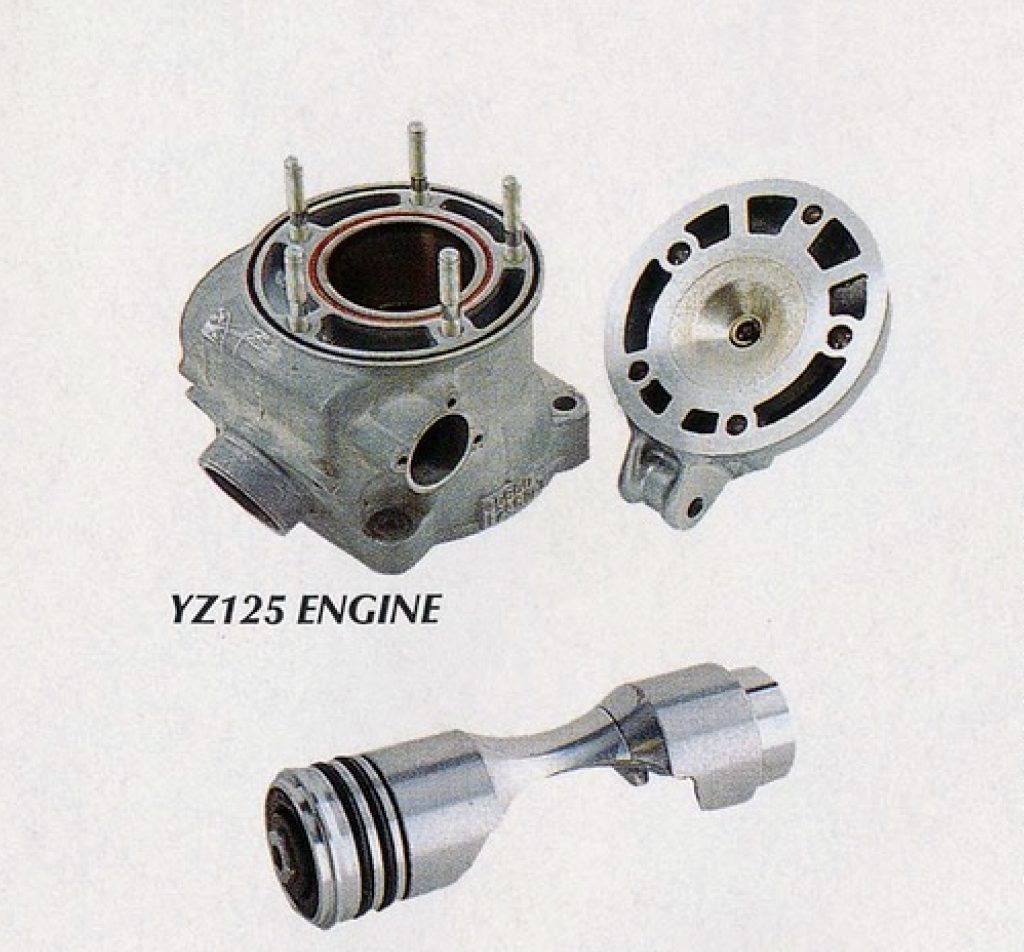

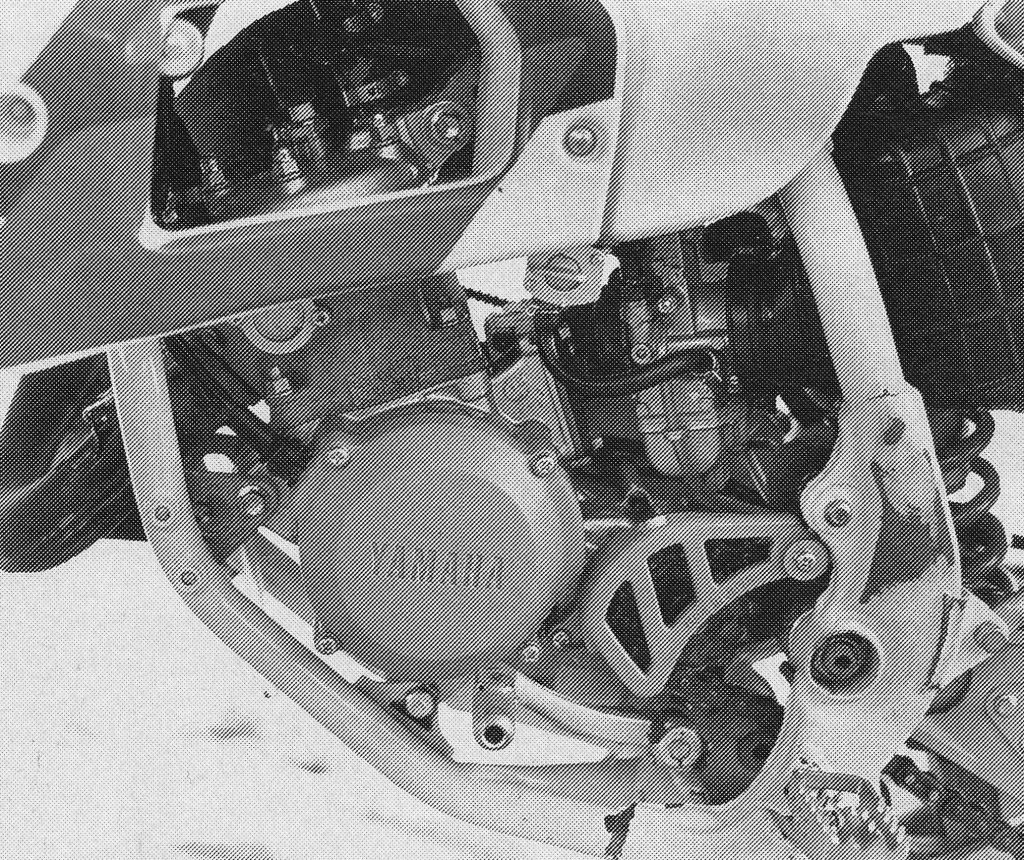

Motor changes for 1992 included an all-new cylinder with revised porting, a reshaped head, and a 3mm smaller YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) drum to reduce heat-related deformation. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Motor changes for 1992 included an all-new cylinder with revised porting, a reshaped head, and a 3mm smaller YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) drum to reduce heat-related deformation. Photo Credit: Yamaha

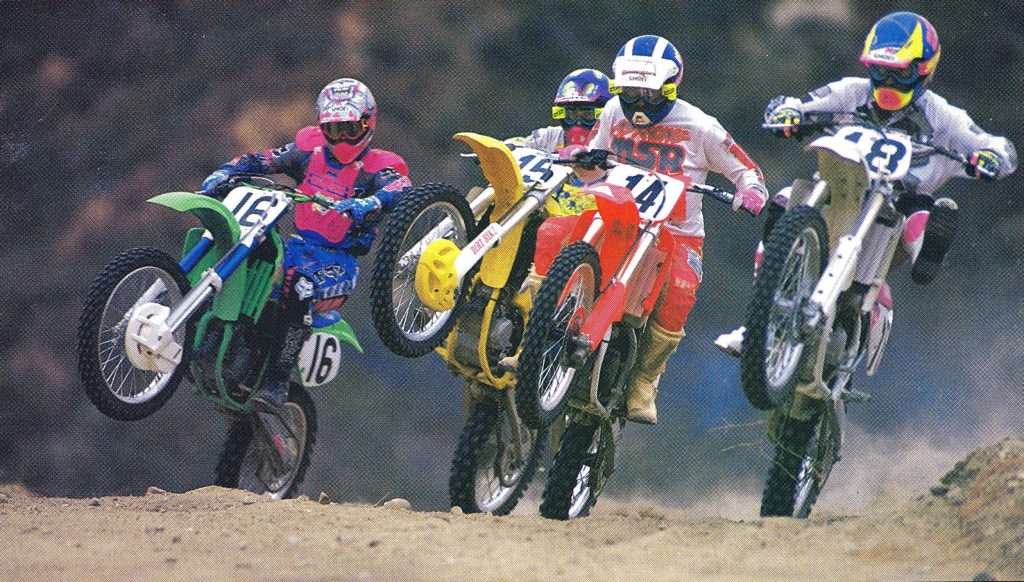

While all the 125s were capable of winning in 1992, putting the YZ at the front required favorable track conditions, quick reflexes, and a talent for keeping the magenta machine in the meat of its razor-thin power profile. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While all the 125s were capable of winning in 1992, putting the YZ at the front required favorable track conditions, quick reflexes, and a talent for keeping the magenta machine in the meat of its razor-thin power profile. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the rear, a revamped Kayaba shock offered 3mm more travel and a new damping system that featured a temperature-compensating valve that was designed to provide more consistent damping performance as the shock heated up. Overall travel clocked in at 12.8 inches with external adjustments available for compression and rebound damping. All-new in 1991, the Monocross linkage returned unchanged for 1992.

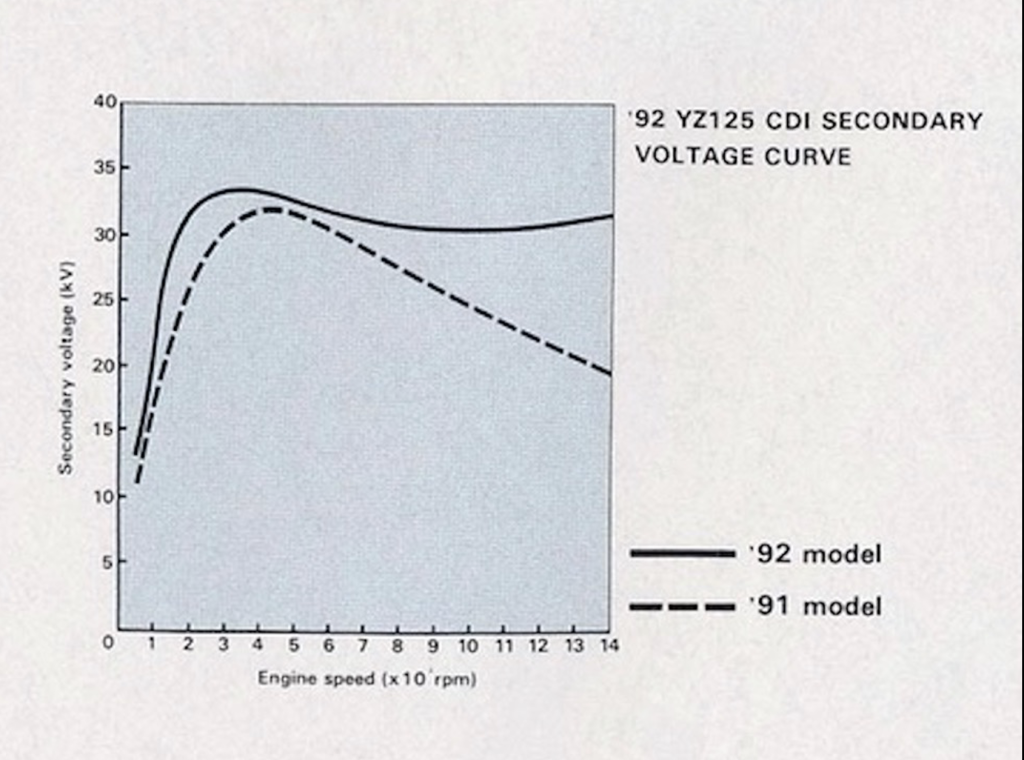

An all-new ignition for 1992 added digital control and a revamped curve aimed at improving throttle response and boosting top-end performance. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new ignition for 1992 added digital control and a revamped curve aimed at improving throttle response and boosting top-end performance. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the chassis front, the YZ125 was mostly a carryover from the year before. The frame was unchanged and featured the same geometry as in 1991. The tank, shrouds, side plates, seat, and rear fender were also 1991 parts. An all-new front fender and number plate freshened up the looks with an appearance many compared to Yamaha’s iconic Y-Zinger minibike. This new front end was more in line with the sleek looks of the rear bodywork and gave the YZ a more cohesive appearance than the 1991’s odd mix of old and new. Both brakes were updated with new reinforced nylon lines for improved feel and redesigned rotors that were more resistant to heat distortion. New pads were also added to provide improved bite and increased longevity. A new front wheel featured straight-pull spokes and a redesigned hub to accommodate the larger front axle. Footpeg width still trailed the massive platforms found on the Kawasaki KX125 but new pegs for 1992 did offer 6mm of additional width for improved comfort. The magenta color scheme of 1991 remained with a subtle change in shroud graphics and the new front bodywork being the only significant visual updates for 1992.

While the YZ was no powerhouse, its chassis was well-regarded for its excellent handling and light feel. Photo Credit: Karel Cramer

While the YZ was no powerhouse, its chassis was well-regarded for its excellent handling and light feel. Photo Credit: Karel Cramer

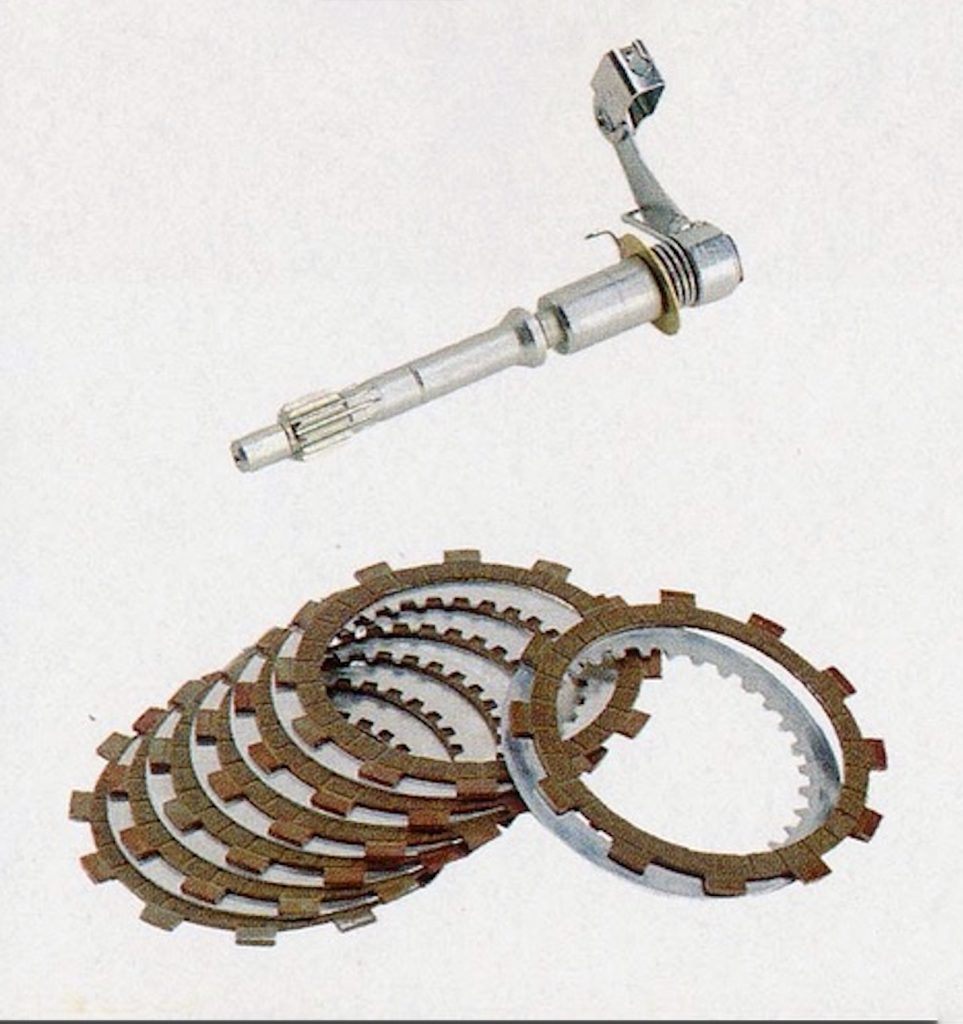

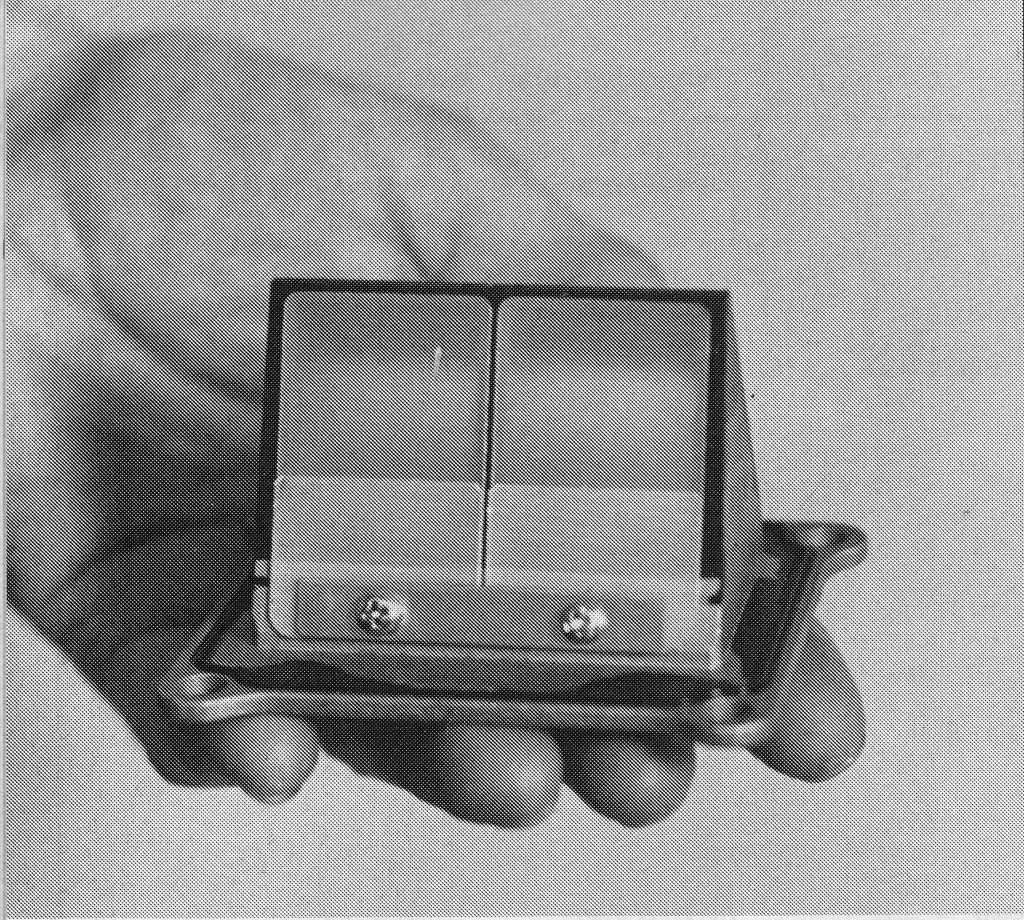

An all-new clutch for 1992 employed a redesigned mechanism for smoother operation and a lighter feel. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new clutch for 1992 employed a redesigned mechanism for smoother operation and a lighter feel. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the track, the new YZ125 turned out to be improved but still quite a bit behind its rivals in the horsepower department. Despite the cylinder and head modifications, the midrange blast of old was still missing in action. What power it did have was still found dead center in the midrange, but it was a far cry from the hard-hitting blast that the YZ125s of the late eighties were known for. This new version of Yamaha’s case reed mill was lethargic off the line, mildly perky in the middle, and lazy on top. To make the YZs narrow powerband work a rider had to fry the clutch out of turns, pin it to the stops, and work the shifter like a cat on a hot tin roof. If you shifted too soon it would bog, and if you revved it out too far, it would throw out the anchor like a chipmunk had chewed threw the sparkplug wire. Making the YZ’s razor-thin powerband work was a delicate operation that required skill and impeccable timing. All three of the YZ125’s competitors were faster and even the notoriously peaky CR125R was easier to keep on the pipe than the one-dimensional Yamaha. The new clutch did work well, but the YZ’s shifting remained the notchiest of the Big Four. The changes made to the transmission in 1991 had improved its action but it was still reluctant to shift under full power and far more stubborn than the silky-smooth cog boxes found on the RM and CR.

A redesigned rotor and a larger front axle graced the front of the YZ125 in 1992. Photo Credit: Yamaha

A redesigned rotor and a larger front axle graced the front of the YZ125 in 1992. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The new forks, beefed-up clamps, and larger front axle paid major dividends for the YZ’s handling in 1992. Front-end traction and feel were greatly improved while high-speed stability remained excellent. It was nimbler than the Kawasaki and far more stable than the Honda or Suzuki. If you were looking for a chassis that could do it all in 1992, then the Yamaha was your best bet. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The new forks, beefed-up clamps, and larger front axle paid major dividends for the YZ’s handling in 1992. Front-end traction and feel were greatly improved while high-speed stability remained excellent. It was nimbler than the Kawasaki and far more stable than the Honda or Suzuki. If you were looking for a chassis that could do it all in 1992, then the Yamaha was your best bet. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In addition to its unimpressive power and clunky shifting, the ’92 YZ’s motor retained the 1991 model’s irritating habit of sputtering in the rough and bogging when landing off jumps. Thankfully, however, this annoyance was easily remedied by replacing the stock reeds with an aftermarket option or by modifying the stock reeds by adding a second set of peddles to prevent flutter. This easy mod perked up the YZ’s low-end response and stopped the annoying sputter and potentially dangerous bog. With a Boyesen Rad Valve installed and an aftermarket pipe, the Yamaha was considerably easier to ride, but if serious power was your goal, extensive cylinder and head mods were the only way to coax competitive power out of the little Yamaha. Jeff Emig’s ultra-fast works YZ125 was proof that there were ponies to be found inside the mill, but they were not going to reveal themselves without a significant amount of work by a knowledgeable tuner.

Despite the numerous motor changes Yamaha threw at the YZ125 in 1992, it remained a disappointing overall performer. Low-end power was barely adequate while top-end power remained non-existent. All of its modest power output was found dead center on the curve with very little available at the extremes. Once on the pipe, it was fairly competitive, but keeping it in the meat of its narrow powerband was tricky and often frustrating. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Despite the numerous motor changes Yamaha threw at the YZ125 in 1992, it remained a disappointing overall performer. Low-end power was barely adequate while top-end power remained non-existent. All of its modest power output was found dead center on the curve with very little available at the extremes. Once on the pipe, it was fairly competitive, but keeping it in the meat of its narrow powerband was tricky and often frustrating. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

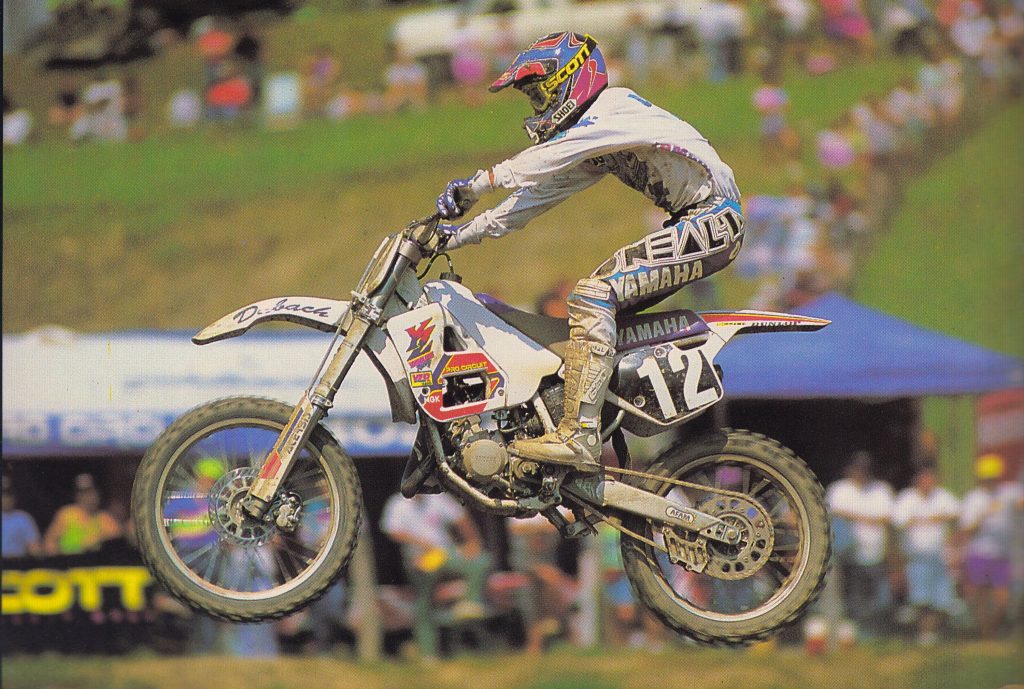

With no Open class machine in the showroom, Yamaha sent Doug Dubach back down to the 125 class in support of Jeff Emig once the 250 Nationals were completed. Doug’s best finish on the 125 would be a 6th place at Steel City in September. Photo Credit: John Valdez

With no Open class machine in the showroom, Yamaha sent Doug Dubach back down to the 125 class in support of Jeff Emig once the 250 Nationals were completed. Doug’s best finish on the 125 would be a 6th place at Steel City in September. Photo Credit: John Valdez

On the handling front, the new YZ125 was significantly improved despite the rather modest list of chassis changes for 1992. Steering precision was much improved, and the bike was admirably adept at changing direction. Most of this improvement could be traced to the new front end which featured stronger clamps, improved damping, and a beefier front axle. These upgrades alleviated much of the previous YZ’s vague front-end feel and provided a good combination of steering precision and high-speed stability. Both the Honda and Suzuki turned sharper but neither one came close to the YZ’s confidence at speed. In the air and on the ground, the YZ felt light and was easy to throw around. Most riders liked the ergonomics and the YZ was a comfortable machine in most respects. It is often said that slow bikes handle well and the YZ’s modest output may have helped it in this category. Overall, the YZ proved to be an admirable handler that comfortably split the difference between the nervousness of the RM and CR and the stubborn turning of the KX.

Pic #16 Noleen Racing’s Kyle Lewis was another hot shoe racing the YZ125 in 1992. Lewis’ best finish of the year would be a 3rd place at Seattle in February behind the Peak Honda duo of Jeremy McGrath and Buddy Antunez. Photo Credit: Jeff Ames

The all-new forks on the YZ for 1992 offered a substantial improvement in performance over the ones found on the 1991 machine. While the stock springs were a bit soft for hard chargers, their overall performance was plush and well-regarded. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The all-new forks on the YZ for 1992 offered a substantial improvement in performance over the ones found on the 1991 machine. While the stock springs were a bit soft for hard chargers, their overall performance was plush and well-regarded. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Some of the credit for the YZ’s capable handling went to its new suspension, which proved a substantial upgrade over 1991. The new 43mm Kayaba forks had none of the ’91 model’s mid-stroke harshness and offered a plush feel that did a great job of gobbling up the kind of small chop that flummoxed the Showa units found on the CR125R. The bottoming feel was good but faster and heavier riders felt stiffer springs were necessary for optimal performance. Overall, they ranked slightly below the Suzuki and Kawasaki forks, but significantly ahead of the harsh forks found on the Honda.

The YZ’s revamped shock for 1992 offered a well-sorted ride that was rated well ahead of the CR but slightly behind the excellent shocks found on the RM and KX. Like the forks, the spring was a bit light for faster and larger riders, but most pilots felt they could happily race the machine with the stock components in place. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The YZ’s revamped shock for 1992 offered a well-sorted ride that was rated well ahead of the CR but slightly behind the excellent shocks found on the RM and KX. Like the forks, the spring was a bit light for faster and larger riders, but most pilots felt they could happily race the machine with the stock components in place. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Out back, the updated shock once again proved an admirable performer. Overall comfort and control were very good with most riders being able to find an acceptable setting with the provided adjustments. It was not as plush as the ultra-smooth KX125 but most riders rated it very well in stock condition. In truth, the biggest hindrance to the YZ’s suspension action was probably its slow motor, which often caused the machine to thud into obstacles the other machines floated over. If you could keep it on the pipe and pulling, the suspension worked very well, but if you lost your drive, it was hard to get the YZ back up to speed.

After a slow start to the ’92 125 season, Yamaha’s Jeff Emig went on a tear in the latter part of the championship chase. Wins at Red Bud, Troy, Washougal, Spring Creek, Broome-Tioga, and Steel City and a rash of bad luck for series points leader Mike LaRocco brought Emig to within 1 point of the series lead going into the final round at Budds Creek. In MD, a broken shifter for Larocco in the first moto would effectively hand Emig the title as he roosted away to a double moto victory and his first 125 National Motocross title. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

After a slow start to the ’92 125 season, Yamaha’s Jeff Emig went on a tear in the latter part of the championship chase. Wins at Red Bud, Troy, Washougal, Spring Creek, Broome-Tioga, and Steel City and a rash of bad luck for series points leader Mike LaRocco brought Emig to within 1 point of the series lead going into the final round at Budds Creek. In MD, a broken shifter for Larocco in the first moto would effectively hand Emig the title as he roosted away to a double moto victory and his first 125 National Motocross title. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

In addition to being slow, the stock ‘92 YZ motor was notorious for sputtering and bogging at inopportune times. To remedy this reed flutter, it was advisable to add a second reed pedal behind the stock ones or replace them with an aftermarket alternative. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In addition to being slow, the stock ‘92 YZ motor was notorious for sputtering and bogging at inopportune times. To remedy this reed flutter, it was advisable to add a second reed pedal behind the stock ones or replace them with an aftermarket alternative. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

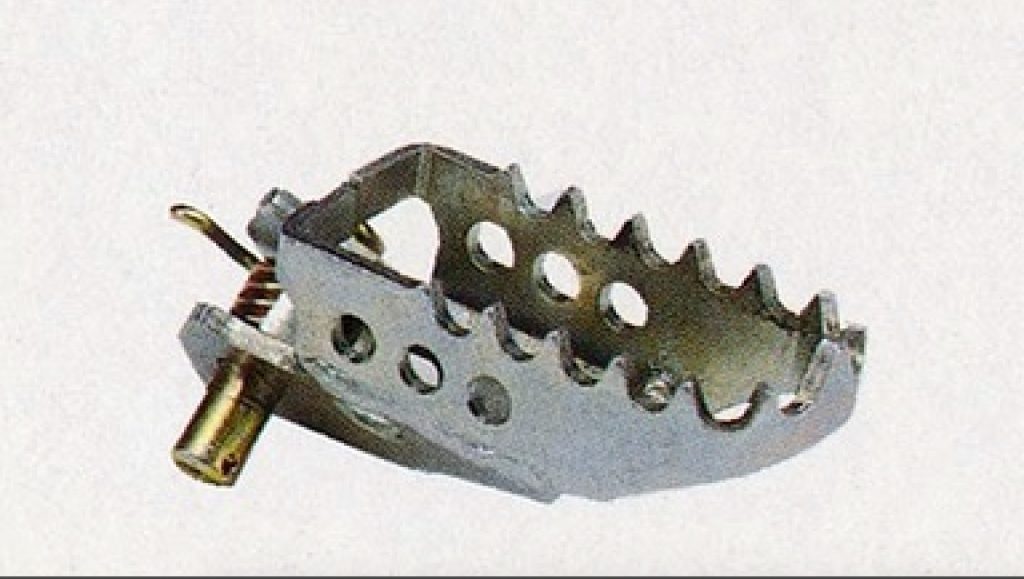

All-new pegs for 1992 added 6mm of width for increased rider comfort and control. Photo Credit: Yamaha

All-new pegs for 1992 added 6mm of width for increased rider comfort and control. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In the details department, the YZ125 was a decent overall performer. Riders praised the sano handholds built into the side plates, comfortable seat, wide pegs, handsome graphics, and updated bodywork. The revamped brakes lacked the “right now” bite of the Honda but performed well in most other respects. The lack of a removable rear subframe seemed like a glaring omission by 1992, but at least one side was removable to make shock access more convenient. The Monocross linkage worked well but it hung down well below the frame and it was possible to catch it on whoops and other obstacles. Thankfully, this was usually more of an annoyance than any real hindrance to performance. The YZ’s bar, lever, and grip quality were poor with the mild steel bars proving far more prone to bending than the tough chromoly units found on the Honda and Kawasaki. Any minor tipover was enough to pretzel the stock bars beyond usefulness. The grips were also notorious for chewing palms and thumbs and most riders replaced them with a Scott or Oakley alternative. Overall fastener quality was unimpressive as well and it was very easy to strip the bolts and Phillips screws holding the Why-Zed together. The stock chain and sprocket were cheap quality as well, but at least the anemic motor did not put a ton of pressure on them. While the engine was slow, it was quite reliable in most respects. As long as the air filter was kept clean and good quality oil was used, the Yamaha was happy to keep buzzing around the track. The tried-and-true YPVS (Yamaha Power Valve System) was also less complicated to service and harder to screw up than most of its competitors.

Kaleidoscope: The 125 class certainly had no lack of color available in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Kaleidoscope: The 125 class certainly had no lack of color available in 1992. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the stock 1992 was notoriously slow, Jeff Emig’s Steve Butler-tuned factory YZ was widely acknowledged to be the fastest machine in the class. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While the stock 1992 was notoriously slow, Jeff Emig’s Steve Butler-tuned factory YZ was widely acknowledged to be the fastest machine in the class. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In the end, the 1992 Yamaha YZ125 proved to be a very good machine in serious need of a heart transplant. The chassis and suspension had what it took to ride at the front, but the YZ’s geriatric mill was too old, too slow, and too hard to ride to keep up with the newer and more robust powerplants making their way into the class. With a savvy tuner at the ready and a talented rider at the controls, the YZ could be a world beater, but in stock condition, it was firmly the caboose of a very competitive 125 train.

Pretty, excellent handling, and well suspended, the 1992 Yamaha YZ125 had a lot going for it in 1992. Unfortunately, the one thing it lacked was the only thing that really mattered in the hotly contested world of 125 racing. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Pretty, excellent handling, and well suspended, the 1992 Yamaha YZ125 had a lot going for it in 1992. Unfortunately, the one thing it lacked was the only thing that really mattered in the hotly contested world of 125 racing. Photo Credit: Yamaha