For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at how the 125 class of 1989 fared in the magazine shootouts of the time.

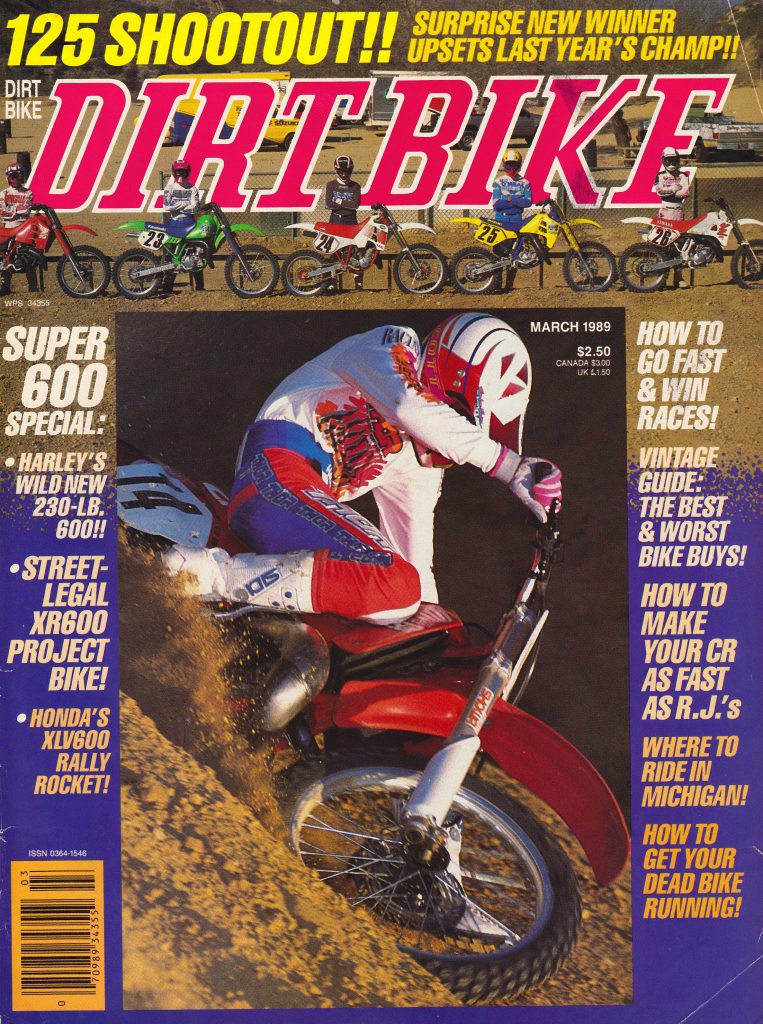

Three of the Big Five 125 contenders were all-new for 1989 with every one of them offering very different flavors on the track. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Three of the Big Five 125 contenders were all-new for 1989 with every one of them offering very different flavors on the track. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The 1989 season was a great time to be racing in the 125 class. This season, all the Big Four Japanese tiddlers received substantial upgrades with Yamaha, Suzuki, and Honda introducing all-new machines. Revamped in 1988, the KX125 did not receive the same glam-up for 1989, but it did adopt significant chassis upgrades and beefy new works-style forks for the new season. Over in Europe, KTM’s 125 added motor and suspension upgrades aimed at making it a mainstream contender against the dominant Japanese. All five machines were remarkably competitive and unlike most other seasons, there was not a real dog in the bunch.

Today, it would be inconceivable to leave KTM out of a motocross shootout, but in 1989, only Dirt Bike included the Austrian in its 125 comparison. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Today, it would be inconceivable to leave KTM out of a motocross shootout, but in 1989, only Dirt Bike included the Austrian in its 125 comparison. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

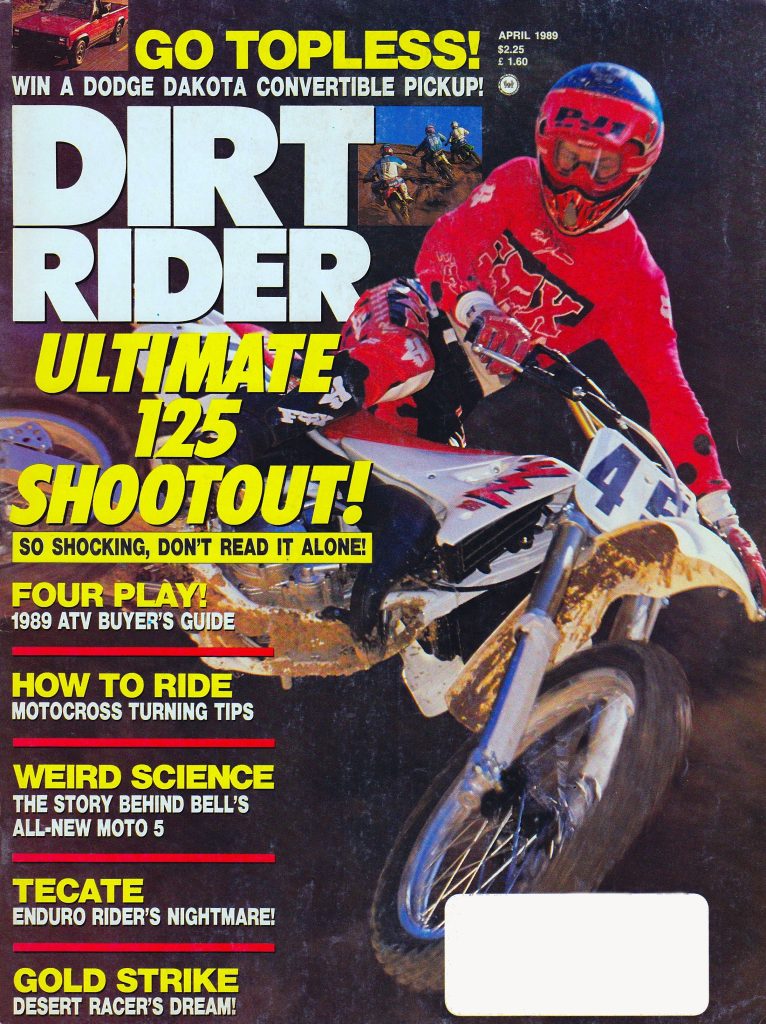

A casualty of the death of print media, the dearly departed Dirt Rider was once the most popular magazine in off-roading. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

A casualty of the death of print media, the dearly departed Dirt Rider was once the most popular magazine in off-roading. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

For this shootout rundown, we are going to look back at the surprisingly varied opinions the magazines had on the contenders in 1989. Today, I think most people would assume that Honda swept these comparisons, but it is interesting to see how much variety in opinion there was at the time. All four Japanese machines had their champions with MXA, Dirt Bike, and Dirt Rider coming to very different conclusions. In 1989, only Dirt Bike included the KTM in their shootout so only their rankings will be reflected in the standings.

As before, I will include a summary of each machine’s final shootout standings and provide a bit of extra information on each bike for additional context.

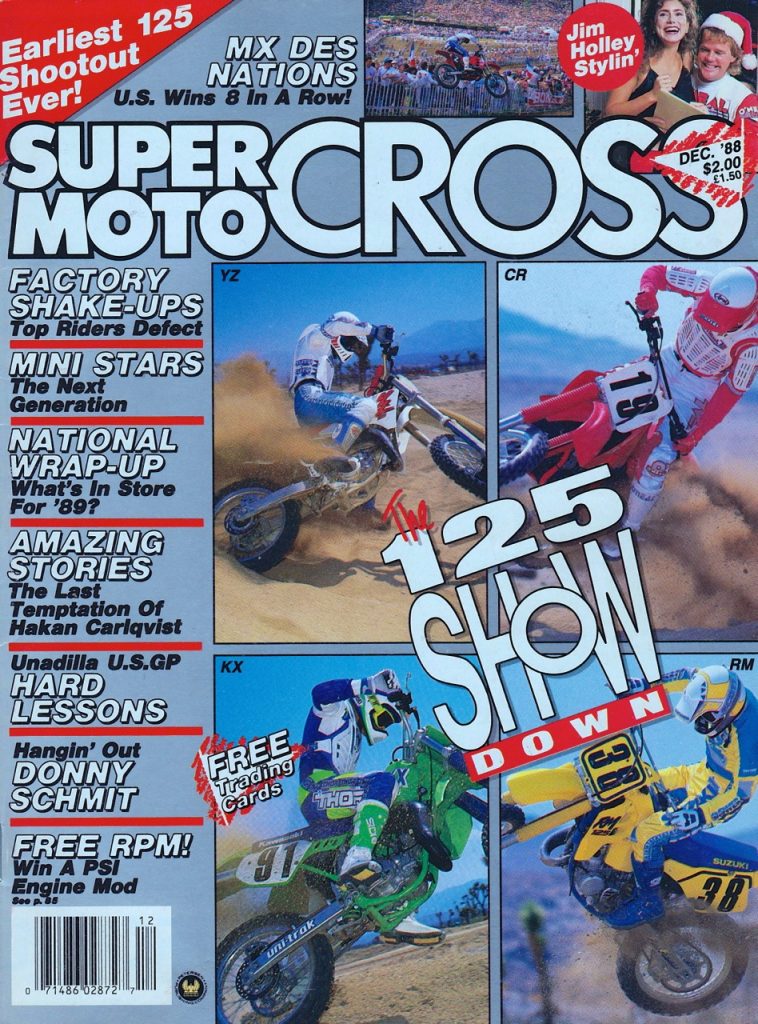

A motocross-focused offshoot of Dirt Rider, Super Motocross was one of my favorite magazines of the late eighties. Unfortunately, its run at the newsstands only lasted three years with Petersen Publishing deciding to fold SMX back into Dirt Rider at the end of 1989. Photo Credit: Super Motocross

A motocross-focused offshoot of Dirt Rider, Super Motocross was one of my favorite magazines of the late eighties. Unfortunately, its run at the newsstands only lasted three years with Petersen Publishing deciding to fold SMX back into Dirt Rider at the end of 1989. Photo Credit: Super Motocross

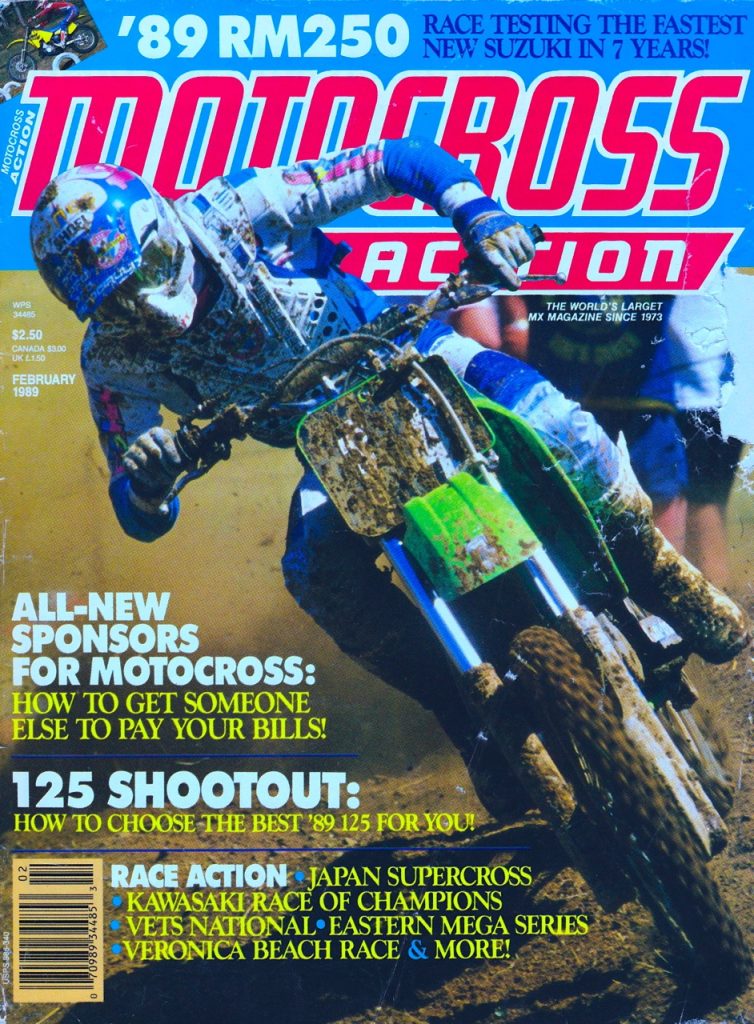

Longtime Wrecking Crew member and AMA pro Larry Brooks graces the cover of MXA’s 125 shootout issue for 1989. In 1988, Brooks raced a KX125 to 6th overall in the 125 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Longtime Wrecking Crew member and AMA pro Larry Brooks graces the cover of MXA’s 125 shootout issue for 1989. In 1988, Brooks raced a KX125 to 6th overall in the 125 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

1989 Honda CR125R Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 1st (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 3rd (out of 5) Dirt Rider – 3rd (out of 4) Super Motocross – 1st (out of 4 ) Photo Credit: Honda

1989 Honda CR125R Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 1st (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 3rd (out of 5) Dirt Rider – 3rd (out of 4) Super Motocross – 1st (out of 4 ) Photo Credit: Honda

1989 Honda CR125R Overview: All new for 1989, Honda’s CR125R adopted the sleek and sexy “low boy” layout introduced on the CR250R in 1988. This new bodywork lowered the machine’s center of gravity and provided the CR with the slimmest and most comfortable ergonomics in the class. Engine changes for ’89 included beefed-up gears, new timing for the ATAC, larger bearings for the connecting rod, improved piston lubrication, an enlarged reed valve, new porting, and a reshaped exhaust. Chassis updates added a new frame with slightly more rake and increased strength in critical areas. All-new rear suspension moved to the CR250R’s “Delta Box” linkage to provide improved performance on hard hits and was paired with a revamped Kayaba damper. Up front, the CR eschewed the trend toward beefier forks by sticking with the same 43mm Showa cartridge units it had employed since 1987. Initially a huge Honda advantage, these forks were quickly becoming a liability as larger 46mm conventional and inverted designs with greater external adjustability were becoming the class norm.

On the track, the 1989 CR125R was defined by one thing – power. The motor changes for 1989 brought back the boost missing the previous year and pleased riders who had been perplexed by the ’88 CR125R’s mellower delivery. There was still not much grunt down low, but once the Honda lit the fuse, it was rooster tails and white knuckles as the red ripper pulled you to the front. From the midrange to the rev limiter, none of the other Japanese machines were as fast as Honda’s CR125R. Novices sometimes struggled with its lack of low-end and potent delivery, but no one felt the CR was anything but a winner in the motor department.

Pro-level power and a feathery feel made the CR the darling of the go-fast set in 1989. Photo Credit: Mike Webb

Pro-level power and a feathery feel made the CR the darling of the go-fast set in 1989. Photo Credit: Mike Webb

Riders also loved the Honda’s new layout and comfy feel. The redesigned seat was taller in the middle and lower in the back, making it easier than ever to climb around the machine in the heat of battle. Excellent brakes, effortless shifting, and a bulletproof clutch also made the Honda’s list of significant advantages. Turning remained a CR strong suit with the red machine carving tight arcs with ease. Headshake under deceleration (also a Honda trademark) was ever present, but most riders felt it was a fair tradeoff for the CR’s nimble manners in the turns.

Where things went pear-shaped for the CR was on the suspension front. The 43mm forks that dominated racing in 1987 were noticeably flexy on hard hits and less accurate feeling than the larger conventional 46mm and inverted units of the competition. The stock spring rates were well sorted but the damping settings Honda chose caused the forks to skitter and deflect on small chop and holes. The forks delivered a harsh spike in the midstroke, and most riders rated them as the worst of the Japanese contenders.

In the rear, the picture was only slightly better with the new Pro-Link delivering a harsh ride that only smoothed out when pushed. Riding the CR like Mike Kiedrowski delivered acceptable results but everyone below his speed found the damper harsh and busy. Braking bumps and small chop flummoxed its damping, and the CR was only happy when in full attack mode. For Sky Cooper and the MX Kied, this was ideal, but for Average Joes, its stock performance was disappointing.

In the end, the CR’s incredible power, sharp turning, and feathery feel were enough to cause MXA and SMX to overlook its other shortcomings. The CR was by far the best bike for pros who loved its endless pull and were unconcerned with its lack of suspension compliance. At Dirt Bike and Dirt Rider, the Honda’s demanding powerband and harsh suspension were enough to knock it out of the top spot against its easier-to-ride rivals.

1989 Suzuki RM125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 3rd (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 2nd tied with the YZ (out of 5) Dirt Rider – 1st (out of 4) Super Motocross – 2nd (out of 4 ) Photo Credit: Suzuki

1989 Suzuki RM125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 3rd (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 2nd tied with the YZ (out of 5) Dirt Rider – 1st (out of 4) Super Motocross – 2nd (out of 4 ) Photo Credit: Suzuki

1989 Suzuki RM125 Overview: Another all-new machine for 1989, Suzuki’s revamped RM125 was a serious return to glory for the beleaguered brand. After dominating 125 racing in the late seventies and early eighties, Suzuki hit hard times with a run of lackluster offerings in the mid-eighties. Quirky styling, flighty powerbands, and poor-quality construction put the once-winning brand on the ropes during this era.

In 1989, however, Suzuki came roaring back with an all-new design that had been developed with the help of six-time AMA champion Bob Hannah. Bob had been hired in 1986 to help turn around Suzuki’s flagging race development team and the 1989 RMs marked the first all-new machines to bear the Hurricane’s stamp of approval.

All-new from the ground up, the 1989 RM125 featured a revamped frame, redesigned power plant, beefed-up suspension, and cutting-edge styling. The new bodywork did away with the oddball shapes and wide panel gaps of previous RMs and replaced them with a sleek and modern design that was as beautiful and up-to-date as anything in the class.

The new chassis was just as thoroughly modern with a fully boxed swingarm pivot, a removable alloy bar for shock access, and much stronger construction. An all-new Kayaba fork was introduced that increased the diameter of the stanchions from 43mm to 46mm for improved flex resistance. As before, the new forks offered a full range of external adjustments for compression and rebound damping. In the rear, a redesigned Full Floater replaced the steel linkage of 1988 with alloy components to save weight and added an all-new Kayaba shock and revamped swingarm. The new swingarm finally moved to a “push style” mechanism for easier and more reliable chain adjustment.

The revamped motor moved to a “case reed” design for 1989 to allow for a straighter and shorter intake tract and added 0.5mm to the motor’s stroke. An all-new cylinder featured revised porting and continued to use Suzuki’s Automatic Exhaust Timing Control (AETC) to vary exhaust port height using a pair of sliding guillotine valves. Carburation duties remained the task of Mikuni’s 35mm “crescent-slide” TMX “Slingshot” design and an all-new “semi-low-boy” pipe and large alloy silencer were employed to move spent gases out of the cylinder.

All the controls were upgraded in 1989 to improve comfort by redesigning the grips, reshaping the levers, and reducing the drag within the cables. All-new brakes increased stopping power by increasing the diameter of the discs by 10mm, enlarging the pads, and moving to a grippier pad material. Bolt and fastener selection for 1989 was much improved with the RM finally moving to a more uniform selection of sizes and designs. This made maintenance much easier than in the past with the RM finally feeling as if it was designed by one cohesive team instead of a bunch of committees that never met each other.

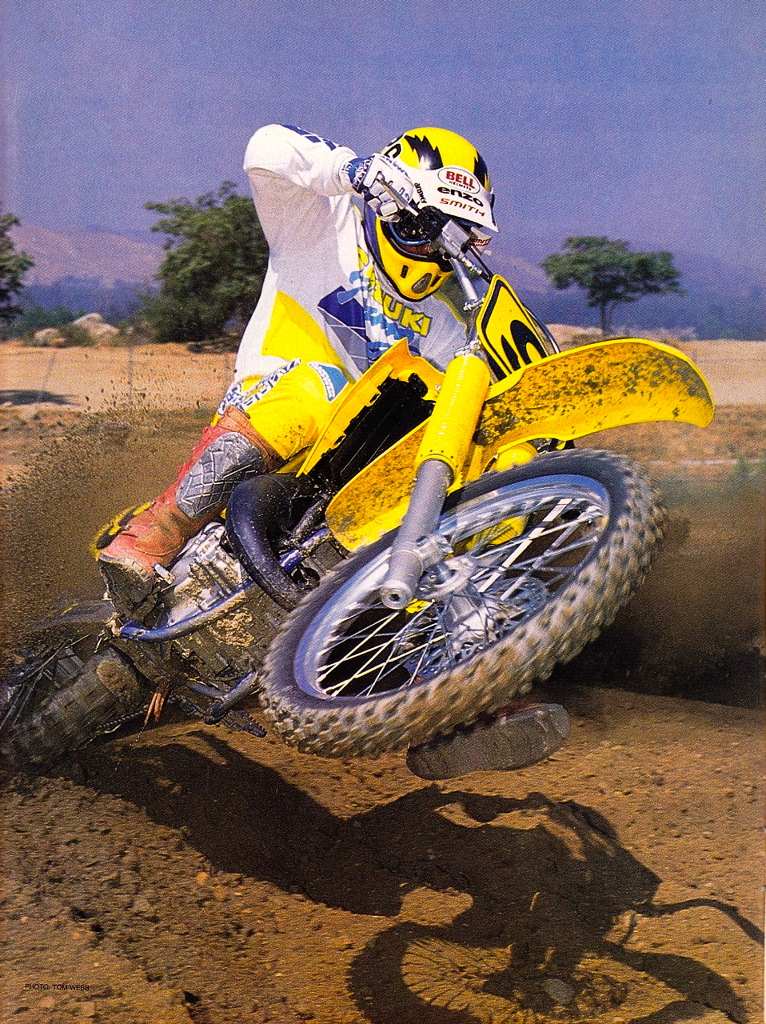

In 1989, nothing in the 125 class was as “right now” fast as Suzuki’s all-new RM125. It ripped out of the hole but threw in the towel too early for fast guys like Bob “Hurricane” Hannah. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

In 1989, nothing in the 125 class was as “right now” fast as Suzuki’s all-new RM125. It ripped out of the hole but threw in the towel too early for fast guys like Bob “Hurricane” Hannah. Photo Credit: Tom Webb

On the track, the new RM125 proved to be a hugely upgraded machine. Riders loved the new layout, super-slick controls, and snappy power. Unlike the ’88 RM125, which was a mid-and-up screamer, the new bike barked out of the hole and pulled super hard into the midrange. This made the RM a great fit for less experienced riders who loved its excellent torque and immediate response. Top-end power, however, was unimpressive and the new bike ran out of steam just as the ’88 RM was getting started. Once past its abrupt low-to-mid hit, the ’89 RM125 had very little power on tap. Revving the yellow machine only made it go slower and it was far more effective to grab another gear rather than try and play rev-limiter roulette with the CR125.

While the new RM was impressively quick from corner to corner, its lack of top-end pull put it at a disadvantage if the track was fast and the straights were long. It was far easier to keep on the pipe than the Honda, but skilled riders often found its short and punchy powerband frustrating. It required twice the shifts per lap compared to the CR, but its clutch was super light and its transmission was buttery smooth. If you kept the shifts coming then the RM was competitively fast, but if you needed to wring it out to the next corner or mistimed a shift, then the Honda was likely to eat you up.

On the chassis front the RM was immensely improved. The new frame was far stronger than in the past and that imparted a solid feel that made the RM a joy to ride, jump, and race. The new Zook offered the sharpest handling in the class with excellent turning that could carve arcs around even standout turners like the CR125. At speed, the RM was quite unsettled, however, and the bike was busy and slightly disconcerting at first. Unlike the CR, it rarely broke out into headshake and most riders got used to its loosey-goosey feel at speed after a bit of saddle time.

As in the past, suspension remained an RM strong suit with the new forks and shock providing some of the best performance in the class. The 46mm KYB forks were noticeably stouter than the 43mm Honda units and provided an excellent feel on the track. Big hits were taken well, and most riders thought they were second only to the ultra-plush Kawasaki forks in performance. In the rear, the new Full Floater proved just as adept at taming the track with a plush feel and excellent control. Johnny O’Mara types felt it was a bit soft for major aerial work, but for most riders below the pro class, it was an excellent stock damper.

In the final standings, it was the RM’s lack of top-end pull that hurt it the most in the magazine rankings. Dirt Rider felt its punchy delivery, razor-sharp turning, excellent suspension, and flickable feel outweighed this deficiency, but all of the other magazines felt it was too big of a handicap to overlook. On looks alone, the RM could have won, and it easily ranked as the most improved machine of the year. For less experienced riders it was an excellent choice, but for expert level 125 racing its lack of fire-breathing horsepower was hard to ignore.

1989 Kawasaki KX125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 4th (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 1st (out of 5) Dirt Rider – 3rd (out of 4) Super Motocross – 3rd (out of 4 ) Photo Credit: Kawasaki

1989 Kawasaki KX125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 4th (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 1st (out of 5) Dirt Rider – 3rd (out of 4) Super Motocross – 3rd (out of 4 ) Photo Credit: Kawasaki

1989 Kawasaki KX125 Overview: In 1989, no other 125 proved as polarizing as Kawasaki’s KX125. Every magazine except Dirt Bike picked it third or fourth, while Super Hunky, Eddie Arnett, and Torquin’ Tim picked it first. Perhaps this was due to their off-road roots where stability and suspension comfort were often valued over outright power. Here the ’89 KX125 excelled, with the best overall suspension package and the most well-rounded handling in the class. Its new 46mm conventional forks were copies of the works forks run by Jeff Ward and Ron Lechien in 1988 and they were excellent in every regard. Fast guys loved their flex-free feel and superb control while mere mortals gushed about their plush action. In the rear, the KX’s Uni-Trak gobbled up the track and floated over bumps and holes that thudded the backside of pilots on the Honda. Big hits and small were taken in stride and the Kawasaki could be pinned through sections that had riders on the other machines puckering up and saying a Hail Mary.

The KX’s handling was equally praised for its do-it-all versatility and confidence-inspiring feel. Geometry updates for ’89 improved turning by steepening the steering angle and a new 19” rear wheel improved tracking and traction out of turns. The new larger forks further improved steering precision with the ’89 KX125 providing notably more accuracy than in the past. Compared to machines like the twitchy RM, the KX was rather slow handling, but very few riders complained about its turning which was something that could not be said of previous KX125s. At speed, the Kawasaki was rock solid and far less anxiety-inducing than the Honda, Suzuki, and KTM. It never shook its head, swapped suddenly, or did anything weird. It just went where it was pointed, whether on the ground or in the air.

With supple suspension, excellent handling, and a broad powerband, the KX125 was competitive, but most riders found it capable rather than captivating in 1989. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With supple suspension, excellent handling, and a broad powerband, the KX125 was competitive, but most riders found it capable rather than captivating in 1989. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For the KX, most of its criticisms centered around its bulky bodywork and uninspired motor. All-new in 1988, the KX’s bodywork and layout were larger and roomier than its competitors. This was great for big guys, but most 125-sized pilots found it gave the KX a heftier feel than its 198 pounds deserved. Aesthetically, the KX’s bodywork also did it no favors but its old-school single radiator and gargantuan rear fender did not affect performance.

On the motor front, porting and KIPS changes for ’89 looked to broaden the ’88 KX’s punchy midrange delivery but most people felt the new motor was a step back from the year before. The new powerband was super smooth and wide but there was absolutely no hit or burst anywhere on the curve. At its peak, it gave up nearly two horsepower to the CR and was even outmuscled by the rather asthmatic RM. It was easy to keep on the pipe and novices liked its broad delivery but even they thought the bike needed a bit more excitement.

On the track, the KX remained competitive despite its mellow delivery. The sure handling, excellent suspension, and electric powerband made it easy to go fast and less tiring than some of the more dramatic machines in the class. It hooked up well out of corners and allowed you to charge the turns and maintain momentum in the rough. Skilled riders could go very fast on the KX but most of them found it less entertaining to ride than the zestier Honda and Suzuki. For MXA, SMX, and Dirt Rider, this lack of verve was enough to knock the competent but slightly boring KX to the back of the standings. At Dirt Bike, the KX’s virtues seemed to find more champions and they ranked at the Kwacker at the top of the class despite the motor’s milk toast personality.

1989 Yamaha YZ125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 2nd (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 2nd tied with the RM (out of 5) Dirt Rider – 4th (out of 4) Super Motocross – 4th (out of 4 ) Photo Credit: Yamaha

1989 Yamaha YZ125 Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – 2nd (out of 4) Dirt Bike – 2nd tied with the RM (out of 5) Dirt Rider – 4th (out of 4) Super Motocross – 4th (out of 4 ) Photo Credit: Yamaha

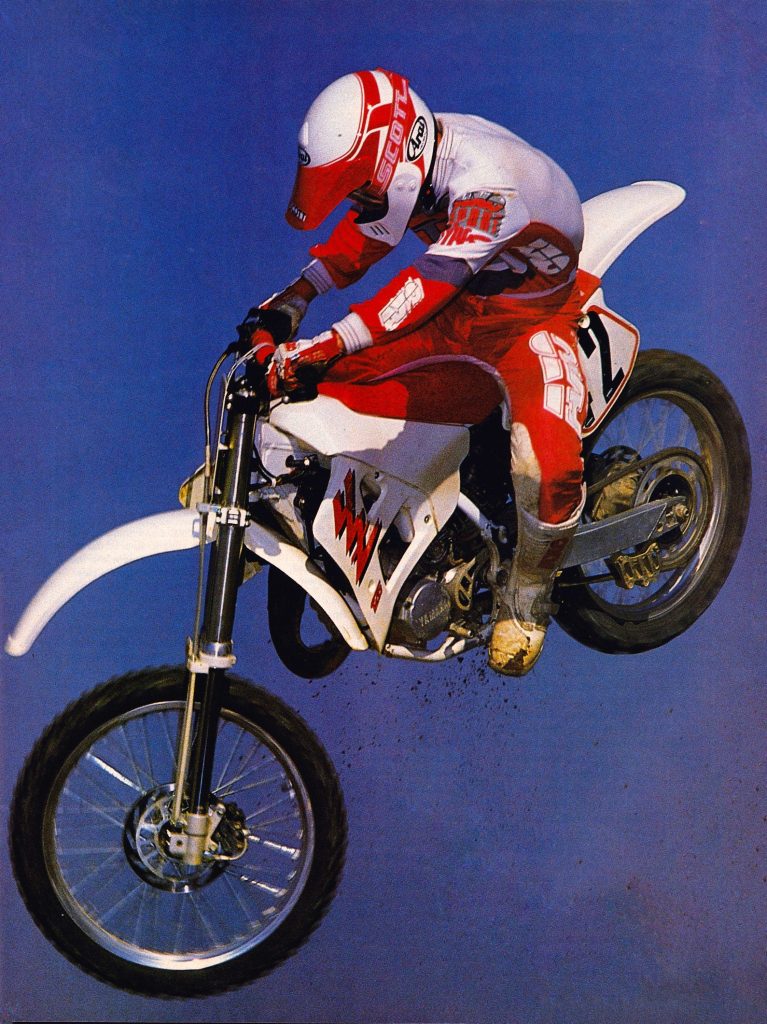

1989 Yamaha YZ125 Overview: Another all-new machine, the YZ125 was an acquired taste in 1989. If you gelled with its unique handling and power characteristics then it was a winner, but if you had difficulty keeping it at a full boil then it was a frustrating bike to ride. In 1988, the YZ had been similarly polarizing with a unique powerband that came on hard in the midrange but turned over very quickly. When it was on the pipe, it was wicked fast, but that burst was short-lived and tricky to use in the heat of battle.

For 1989, Yamaha looked to broaden the YZ’s power spread by reshaping the profile of the power valve, revising the porting, flattening the dome of the piston, increasing the stroke, streamlining the intake tract, and moving to Nikasil for the cylinder liner. A 1mm larger carburetor was added and paired with an all-new exhaust and freer-breathing airbox. A redesigned clutch aimed to improve the old unit’s grabby action and a redesigned transmission altered the primary gear ratio to improve shift action and revised ratios to optimize performance.

In addition to the extensive motor changes the YZ125 adopted an all-new look for 1989. Originally debuted on the YZ250 in 1988, the 125’s new YMZ-inspired bodywork lowered the radiators and fuel cell to better centralize mass and improve rider comfort. The new layout was lower and longer, with a flatter seat and repositioned bars and pegs.

An all-new frame underpinned the YZ and featured revised geometry and much greater strength using a rectangular downtube and fully boxed swingarm pivot.

On the suspension front, Yamaha became the first Japanese manufacturer to go inverted with the addition of Kayaba’s all-new 41mm inverted cartridge fork. Yamaha claimed the inverted design was superior to the old 43mm conventional forks due to its larger diameter clamping area and an additional 30% internal overlap which produced much less flex under a load. In addition, the inverted design also reduced the chance of catching the forks in a rut due to its reduced underhang below the front axle.

Good looks, high-tech suspension, and a potent midrange engine were not enough to outshine the YZ’s competition in 1989. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

Good looks, high-tech suspension, and a potent midrange engine were not enough to outshine the YZ’s competition in 1989. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

In the rear, the YZ featured a redesigned Mono Cross linkage with a more progressive leverage ratio and beefed-up swingarm. The shock duties were handled by Kayaba with a full range of adjustments for compression and rebound damping. As with the Kawasaki, Yamaha decided to move to a larger 19” rear hoop for ’89 to provide an improved feel and increased traction on hard surfaces.

On the track, the YZ was much improved over the 1988 machine. The new layout was comfy and easy to move around on, but some taller riders found the relationship of the bars, seat, and pegs to be a bit cramped. The YZ’s handling was improved as well but most riders felt it was the least precise of the four Japanese machines. In soft terrain, it would occasionally tuck the front end and on hardpack to was prone to a push. It was generally a very stable machine at speed, but some riders reported a very un-Yamaha-like headshake under deceleration. None of the ‘89 125s were terrible handlers, but most riders seemed to agree that the Yamaha was the most unpredictable of the Big Four in 1989.

On the motor front, the Yamaha continued to be a rocket in the midrange but there was not a lot of excitement above or below this pop in the middle. It was a bit less torquey down low and pulled a bit farther on top than the1988 Why Zed, but the Yamaha remained more or less the same midrange mauler it had been since the case reed motor was introduced in 1986. When it was on the pipe, the YZ was as fast or faster than anything else in the class, but that burst was very short and it was critical to time each shift perfectly to prevent falling off the pipe.

Unfortunately, however, the YZ’s transmission was not up to being a willing partner in this endeavor. The transmission updates for ’89 improved the shifting feel considerably but the Yamaha’s cog box remained the most stubborn shifter of the Japanese machines. It was nearly impossible to shift under power without backing off the throttle and feeding in a bit of clutch. This was not ideal on a 125 with a notoriously narrow power spread.

Despite the trick new forks, the YZ turned out to be a disappointing suspension performer in 1989. The inverted KYB forks offered decent damping, but the stock springs were too soft for most riders’ taste. In stock condition, they ranked behind the CR, but with stiffer springs they passed the harsh Showas in the fork standings. Out back, the new Mono Cross was the exact opposite with a stiff feel that worked well on hard hits but jackhammered the pilot’s rear on small chop. In stock condition, the YZ was completely unbalanced, and this may have played a significant role in its slightly unpredictable handling.

In the end, the new YZ125 offered a lot of promise but it was too unpolished to challenge the other Japanese contenders for the top spot in the standings. MXA and Dirt Bike loved its hard-hitting power, but the other magazines found its narrow powerband and recalcitrant shifting too much of a handicap to overlook. With some suspension tuning and a Race Tech shifter, the YZ could be a winning package, but in stock condition it was a step behind its Nipponese rivals in 1989

1989 KTM 125MX Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – N/A Dirt Bike – 5th (out of 5) Dirt Rider – N/A Super Motocross – N/A Photo Credit: Yamaha

1989 KTM 125MX Shootout Rankings: Motocross Action – N/A Dirt Bike – 5th (out of 5) Dirt Rider – N/A Super Motocross – N/A Photo Credit: Yamaha

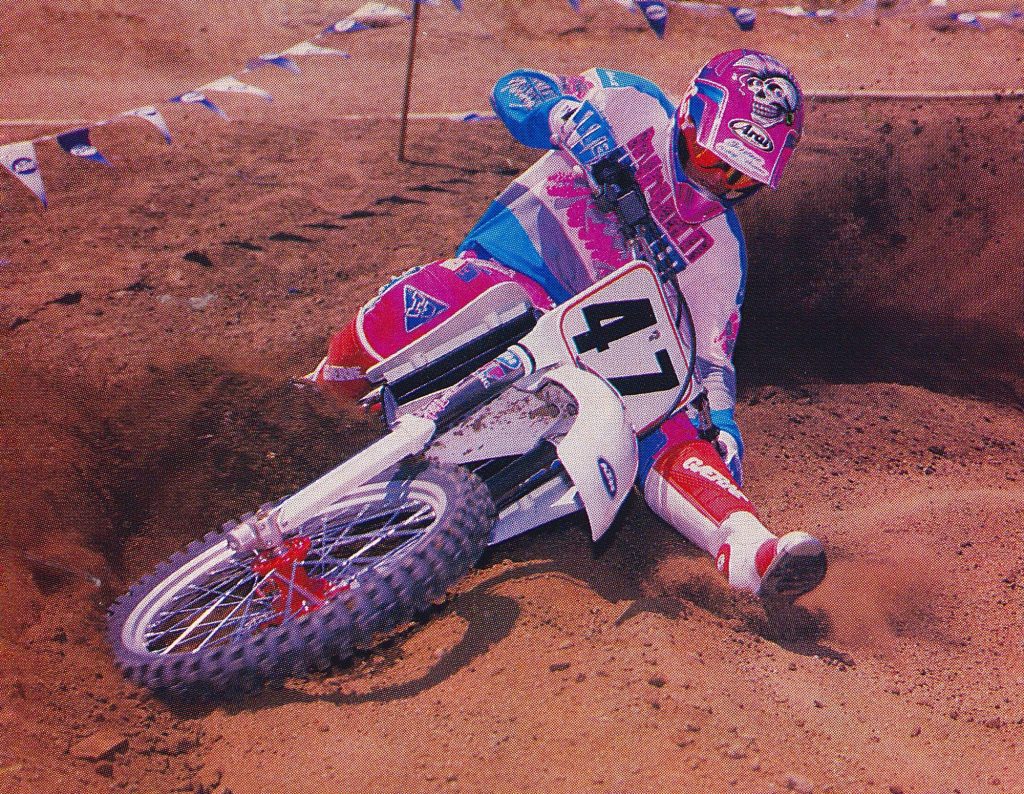

1989 KTM 125MX Overview: Today, KTM is a motocross powerhouse, but in 1989 they were largely an afterthought in the American motocross market. They were quite successful off-road and were well respected in Europe, but over here the magazines rarely included them in motocross shootouts and often did not even bother to test them. In 1989, only Dirt Bike included the KTM in their shootout despite the machine’s reputation for advanced technology and blistering horsepower.

All-new in 1987, KTM’s 125 received several significant improvements for 1989. New frame geometry pulled in the rake slightly, changed the fork offset, and repositioned the swingarm pivot to improve handling. Updated White Power 4054 inverted forks featured revised valving and external adjustments for compression and rebound damping. An updated Pro-Lever linkage and White Power Super Adjuster shock were added and paired with new Brembo calipers and an enlarged front rotor. Motor changes for 1989 included updated porting, beefed-up transmission gears, a stronger clutch, and a larger float bowl for the 37mm Dellorto carb.

On the track, the 1989 KTM 125MX was an absolute rocket. From the midrange on up it was the fastest 125 in the shootout and even outmuscled the blazing fast CR125R. Low-end power was unimpressive, but once the KTM caught fire it was the horsepower champ of 1989. Like the Yamaha, however, the KTM’s problem was converting all that firepower into forward thrust. Both the clutch and transmission were unrefined with a heavy feel and imprecise engagement. Shifting action was very notchy and it was hard to get a positive shift under power. The clutch pull felt like was more suitable for an Open-class bike and most riders found the KTM more tiring to ride than its competition. In a flat-out drag race the KTM was wicked fast, but once you threw in the hills, turns, and off-cambers of a motocross course its powertrain shortcomings became quite apparent.

KTM’s 125 was a bit of an underdog in 1989 but talented riders like Mike Healy could use the Austrian’s prodigious power output to give the Japanese a run for their money. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

KTM’s 125 was a bit of an underdog in 1989 but talented riders like Mike Healy could use the Austrian’s prodigious power output to give the Japanese a run for their money. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Like the motor, the KTM’s suspension was filled with potential, but the settings KTM chose for their 125 handicapped its appeal. Both the trick 4054 forks and Super Adjuster shock were set up too softly for Dirt Bike’s tastes. The soft springs and quick rebound damping probably worked well on the fast and smooth tracks of Europe, but they were out of step with what American testers were comfortable with.

On the handling front, the KTM was rather unpredictable with excellent front-end traction on hardpack but a vague steering feel on softer surfaces. It was hard to trust the front end in sand and mud and the KTM was known to break into Honda-like fits of headshake at speed. Bigger riders appreciated its roomy ergonomics, but its large and tall layout made the KTM feel heavier and less nimble than the Japanese 125s.

In Europe, the KTM proved its mettle by taking Trampas Parker to the 1989 125 World Motocross title, but over here it remained an underdog to the Japanese. Dirt Bike was impressed by its remarkable power output but everything else about the Katoom was a tick off its rivals. It was certainly competitive with a bit of fine-tuning, but that last bit of refinement was left up to the KTM’s owner to sort out.