For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Suzuki’s 2000 RM125.

Suzuki’s RM125 entered the 2000 season in the last year of its current design cycle. With an all-new machine on tap for 2001, Suzuki’s engineers focused on refining rather than redesigning their proven 125 package. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Suzuki’s RM125 entered the 2000 season in the last year of its current design cycle. With an all-new machine on tap for 2001, Suzuki’s engineers focused on refining rather than redesigning their proven 125 package. Photo Credit: Suzuki

During the 1990s, few machines in motocross were as successful as Suzuki’s venerable RM125. During the grunge decade, team Yellow Magic often struggled in the 250 class, but their 125s were always at or near the top of the 125 standings. The eighth-liter RMs were rarely the fastest bikes in the class, but their combination of excellent handling, well-sorted suspension, and easy-to-use power often outclassed faster, but more flawed rivals. If you bought an RM125 in the nineties, you knew you were getting a machine that could win right out of the crate.

Majorly revamped in 1996, Suzuki’s late nineties RM125s were loved for their lithe handling and snappy power. Never the fastest machines in the class, their blend of sharp handling, supple suspension, and excellent power placement won them many fans during this era of 125 racing. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Majorly revamped in 1996, Suzuki’s late nineties RM125s were loved for their lithe handling and snappy power. Never the fastest machines in the class, their blend of sharp handling, supple suspension, and excellent power placement won them many fans during this era of 125 racing. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Launched in 1996, Suzuki’s late nineties RM125 platform was a radical departure from the machine it replaced. Redesigned from the ground up, the 1996 RM featured an all-new frame, revamped motor, sleek new bodywork, and a radical departure in suspension design. After half a decade of experimenting with inverted forks, Suzuki chose to return to a conventional fork in ’96 and its return was met with endless pages of gushing praise. Riders and magazine editors alike loved the performance of the all-new Showa conventional forks with the redesigned RM taking the win in Dirt Bike’s 1996 125 shootout.

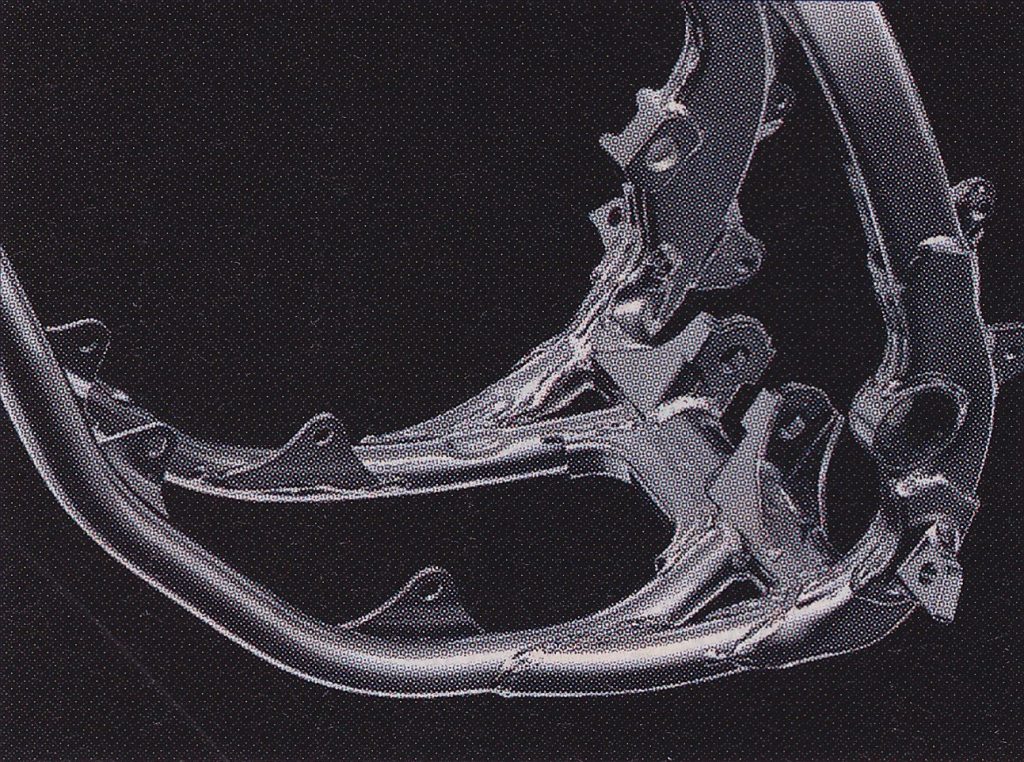

A new lower frame cradle for 2000 provided increased strength by adding additional gusseting and repositioned the main frame tubes closer to the linkage mount to reduce flex. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A new lower frame cradle for 2000 provided increased strength by adding additional gusseting and repositioned the main frame tubes closer to the linkage mount to reduce flex. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While the return to conventional forks was praised by the masses, its appeal at the professional level was far less resounding. The ultra-plush feel that Average Joes adored was the exact opposite of what riders like Mike LaRocco, Jeremy McGrath, and Greg Albertyn were looking for out of their front end. They needed the additional rigidity that the inverted designs provided and by 1999, Suzuki had given up the good fight and retired the beloved 49mm conventional Showa forks for good.

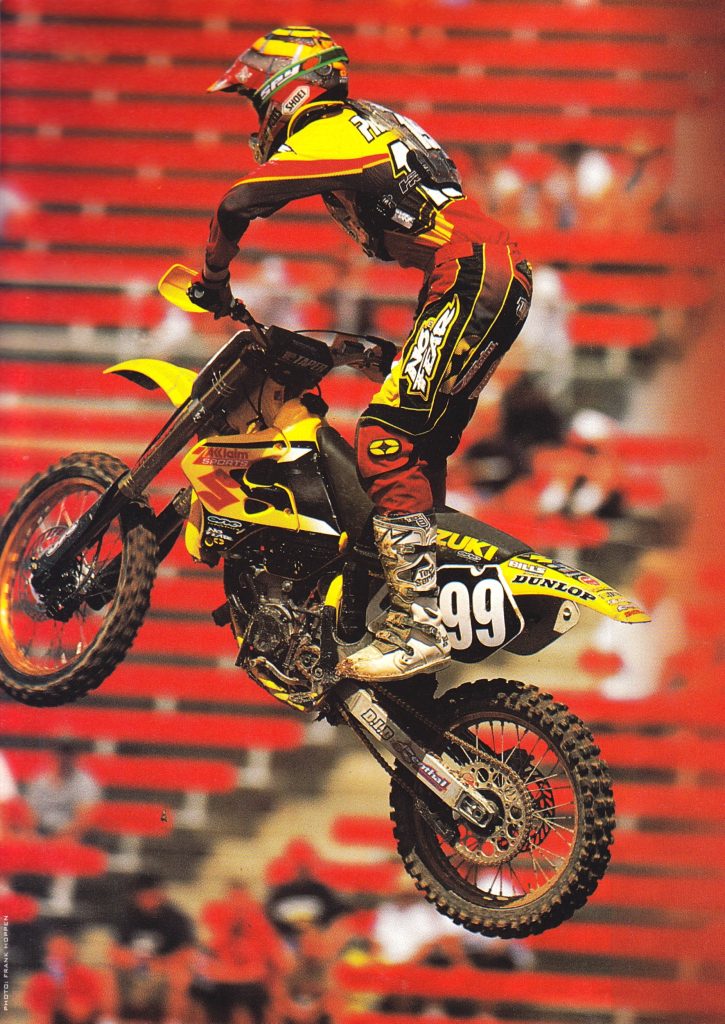

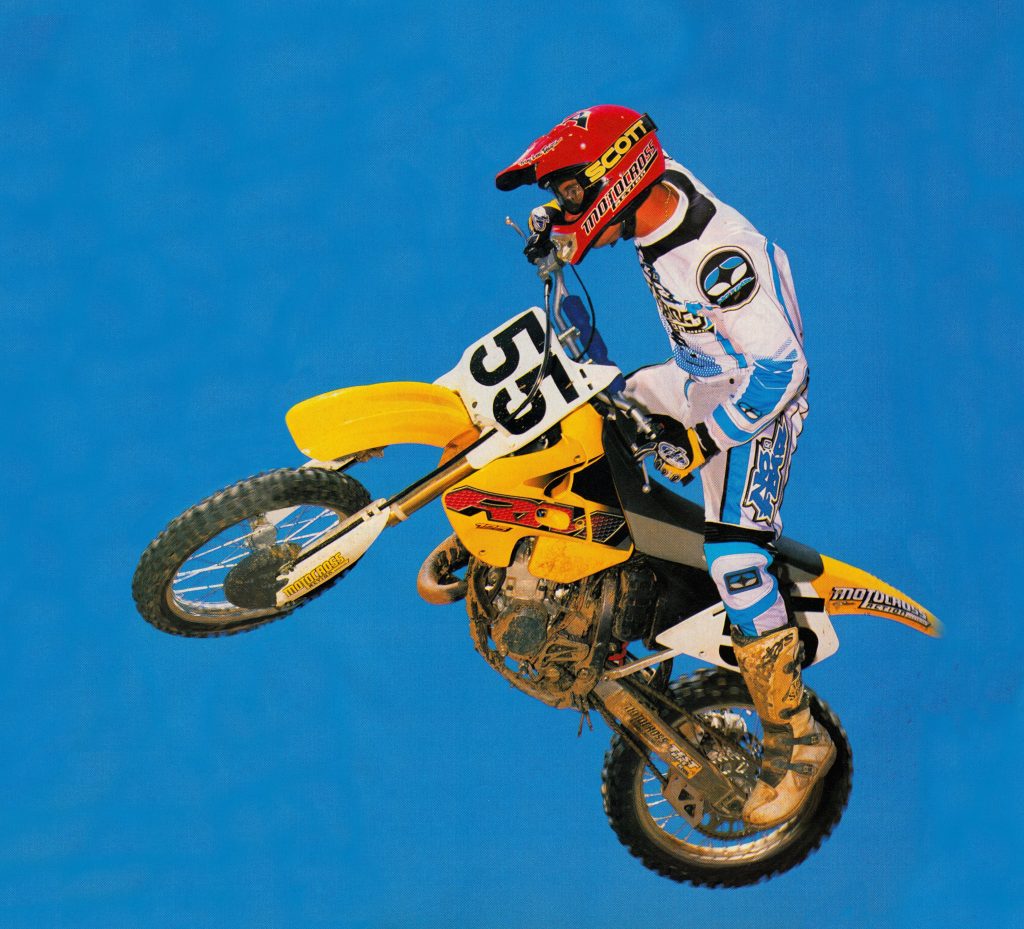

One of the biggest stories of the 2000 season was the arrival of freestyle and motocross phenom Travis Pastrana to the pro ranks. Travis’ flashy style and charismatic personality had many pegging him as the sport’s next superstar before he even entered his first pro race. Photo Credit: Frank Hoppen

One of the biggest stories of the 2000 season was the arrival of freestyle and motocross phenom Travis Pastrana to the pro ranks. Travis’ flashy style and charismatic personality had many pegging him as the sport’s next superstar before he even entered his first pro race. Photo Credit: Frank Hoppen

In addition to returning to an inverted fork in 1999, Suzuki also made one of the strangest styling choices since the introduction of Honda’s infamous ‘hangnail” front numberplates in 1981. From 1996 through 1998, the RM125 had been one of the cleanest and most attractive machines in the class. While some derided its looks as being a clear Honda knock-off, there was no denying that Suzuki RMs were handsome machines.

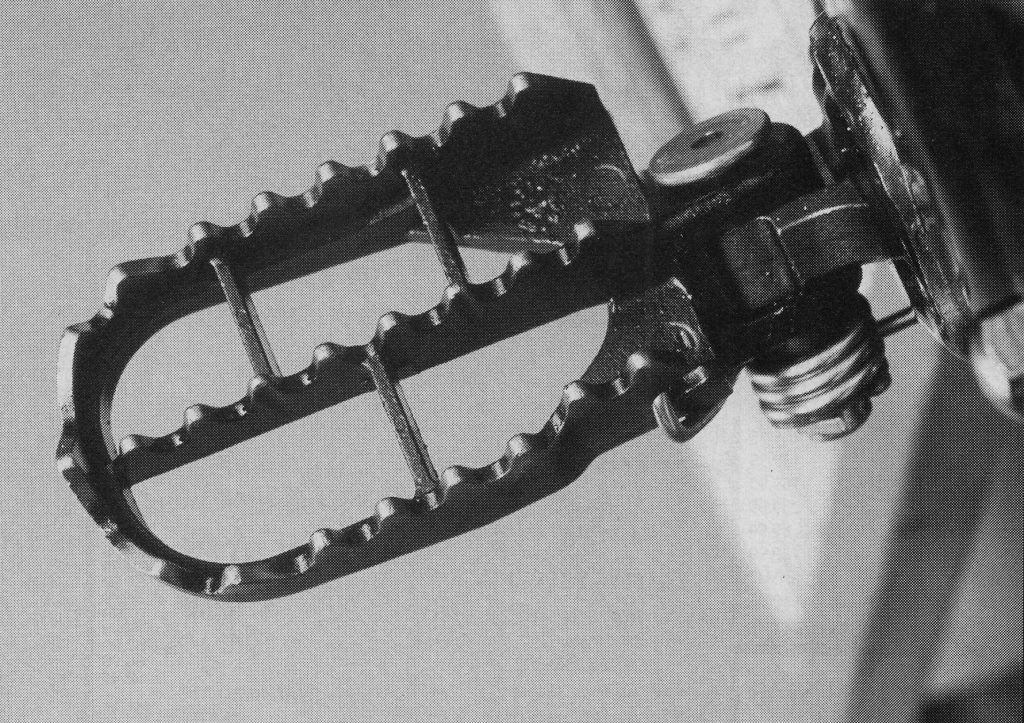

New pegs for 2000 increased rider comfort by adding a third reinforcement down the middle and extending the with of the pegs by 6mm. Photo Credit: Suzuki

New pegs for 2000 increased rider comfort by adding a third reinforcement down the middle and extending the with of the pegs by 6mm. Photo Credit: Suzuki

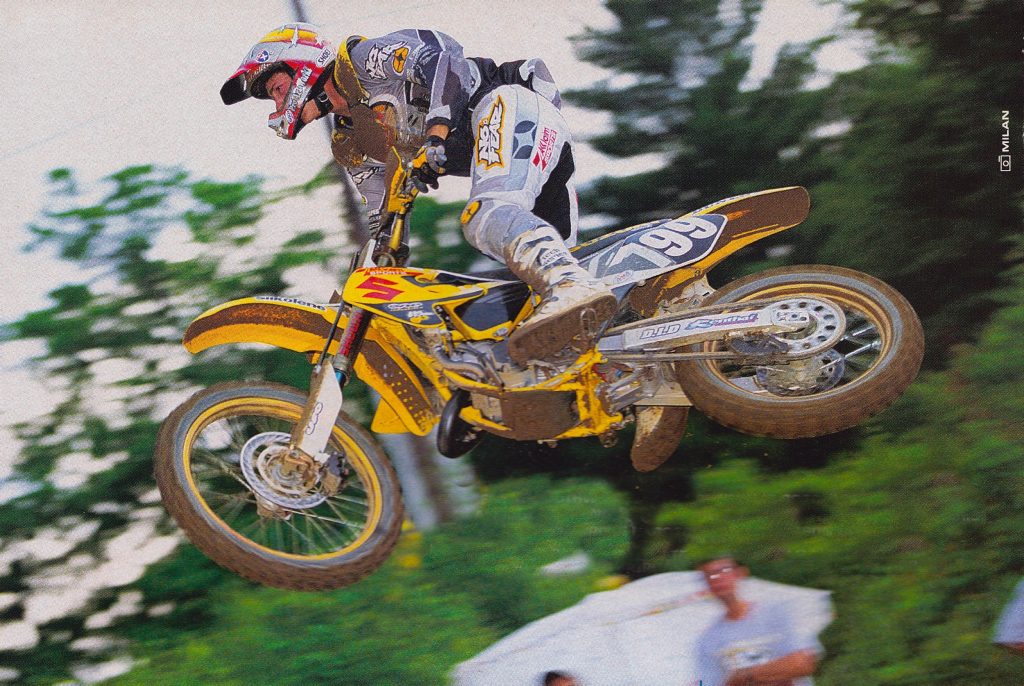

In 1999, one of the more controversial changes made to the RM was the addition of a set of very large radiator shrouds designed to funnel more air to the radiators. While effective at this task, their wide profile and unsubtle looks were not a huge hit with many who preferred the cleaner looks and narrower profile of the 1996-1998 design. In 2000, the factory Suzuki squad went back to the pre-’99 design and the difference in the shroud’s width can be seen in this photo from Washougal by comparing the Suzukis of Travis Pastrana (199) and Lance Smail (71). Photo Credit: Chris Greenberg

In 1999, one of the more controversial changes made to the RM was the addition of a set of very large radiator shrouds designed to funnel more air to the radiators. While effective at this task, their wide profile and unsubtle looks were not a huge hit with many who preferred the cleaner looks and narrower profile of the 1996-1998 design. In 2000, the factory Suzuki squad went back to the pre-’99 design and the difference in the shroud’s width can be seen in this photo from Washougal by comparing the Suzukis of Travis Pastrana (199) and Lance Smail (71). Photo Credit: Chris Greenberg

For 1999, Suzuki removed the trim and stylish radiator shrouds in use since ’96 and bolted on a set of massive ram scoops that looked more akin to a pair of garden shovels than anything that belonged on a slim and sleek racer. The new shrouds were designed to funnel more air to the radiators but overheating was not an issue on the old RMs so this change seemed an odd one to most. In addition to radically altering the lines of the bodywork, the new shrouds gave rise to the “ROM” era of RM styling with Suzuki adding a large “RM” graphic that flowed from the seat to the front of the massive new shrouds. If you closed one eye and squinted, then the “RM” could be seen, but to most casual observers it looked like the decals spelled out “ROM” due to the large hole in the shroud designed to let air pass through. Thankfully, at least, the stock graphics were of terrible quality and quickly removed themselves, saving riders the indignity of explaining what exactly a ROM125 was to their trackmates.

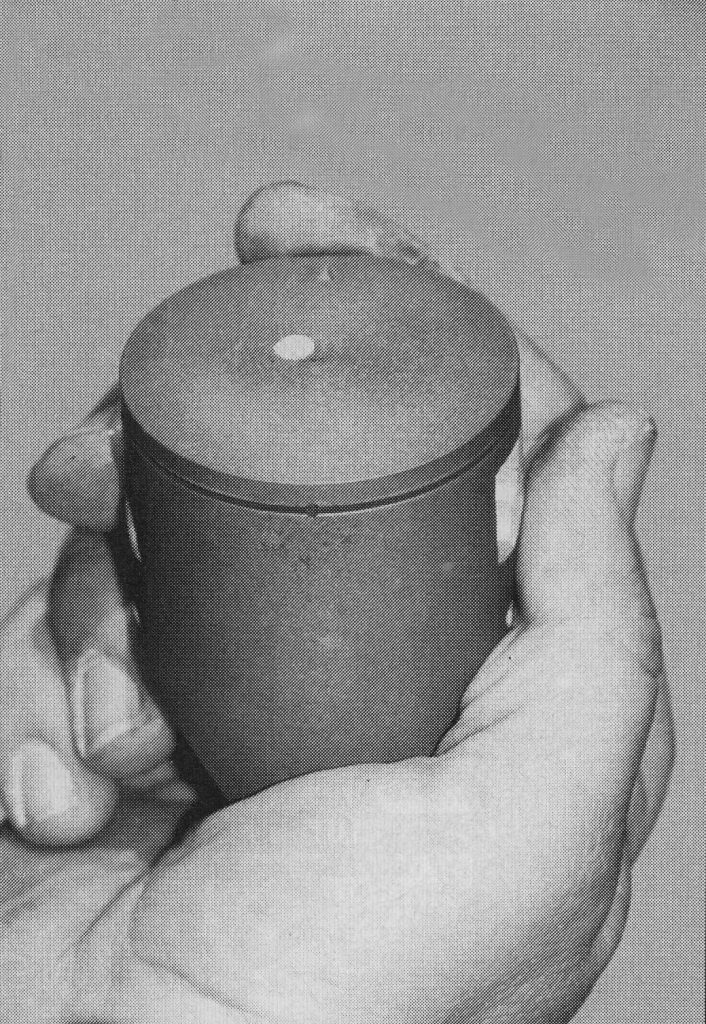

An all-new piston for 2000 repositioned the ring locating pin to the rear to reduce the chance of snagging a ring on the exhaust port. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

An all-new piston for 2000 repositioned the ring locating pin to the rear to reduce the chance of snagging a ring on the exhaust port. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 2000, the biggest news in the 125 class was the arrival of Honda’s second-generation alloy frame and redesigned CR125R. While the CR was much improved, its horsepower deficit to Yamaha’s YZ125 held it back from reclaiming the top spot in the minds of many. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 2000, the biggest news in the 125 class was the arrival of Honda’s second-generation alloy frame and redesigned CR125R. While the CR was much improved, its horsepower deficit to Yamaha’s YZ125 held it back from reclaiming the top spot in the minds of many. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In addition to the new forks and the fighter jet ram scoops, Suzuki added several motor updates and a new 38mm “Power Jet” carburetor to boost power for 1999. The result was a very competitive 125 racer. The revamped motor was not as brawny as the YZ or as shrieking on top as the rev-it-to-the-moon KTM, but its powerband was snappy, well-placed, and easy to ride. The new inverted forks were not as well-loved as the old conventional Showas, but they got the job done and were good enough in stock condition for most rider’s tastes. The RM’s turning was without peer and the yellow machine could carve under, over, and around any of its rivals. At speed, it remained slightly schizoid, but this was an RM trait that most riders had become accustomed to by 1999. No one much cared for the new shrouds which bulged out at the front and caught rider’s boots in the turns, and finding neutral remained an aggravating game of roulette, but overall, the 1999 RM125 was a capable racer.

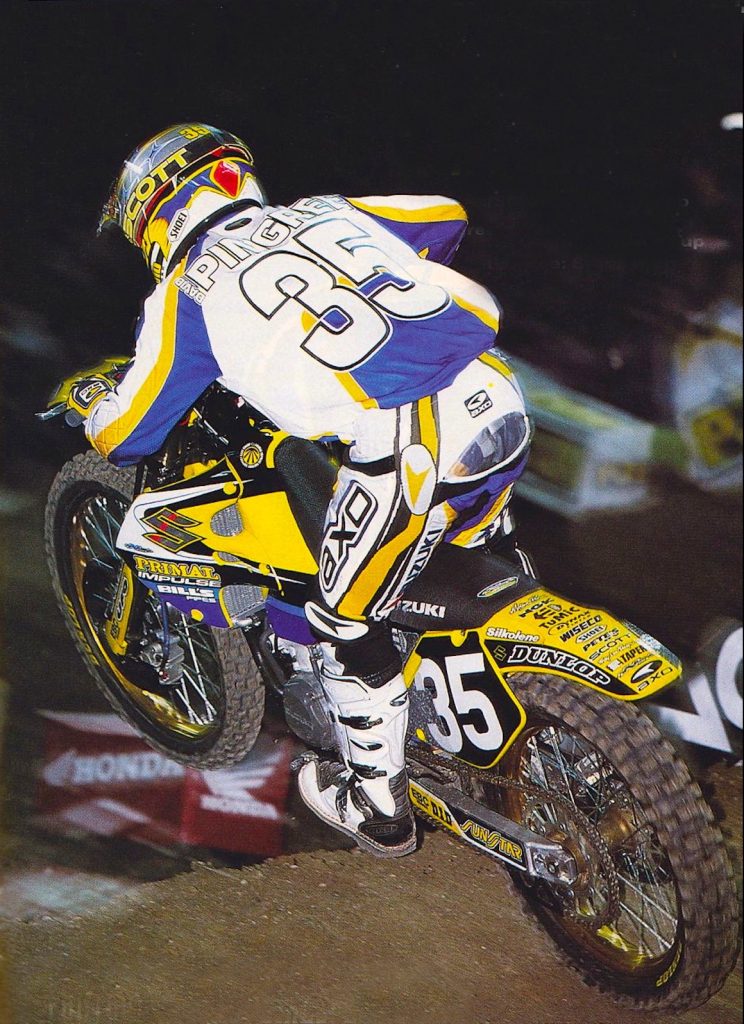

While Travis Pastrana garnered the majority of Suzuki’s press in the 125 class he was far from their only star in 2000. Primal Impulse’s David Pingree put his RM125 consistently at the front winning Anaheim One and missing out on the 125 West Supercross title by a mere 2 points to Pro Circuit’s Shae Bentley. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While Travis Pastrana garnered the majority of Suzuki’s press in the 125 class he was far from their only star in 2000. Primal Impulse’s David Pingree put his RM125 consistently at the front winning Anaheim One and missing out on the 125 West Supercross title by a mere 2 points to Pro Circuit’s Shae Bentley. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With an all-new machine in the wings for 2001, Suzuki entered the last year of the 1996 RM’s design cycle with a list of refinements for their proven 125 platform. Riders already loved the RM’s feathery feel and quick handling, so the chassis updates were limited to additional reinforcements to the lower cradle to increase rigidity. The shock mounting was also beefed up to reduce flex and the detachable alloy subframe was shortened by 10mm to improve ergonomics. A new swingarm was added with a 10mm increase in the height of the cast portion for added strength and the diameter of the rear axle was enlarged by 2mm to provide a more precise handling feel.

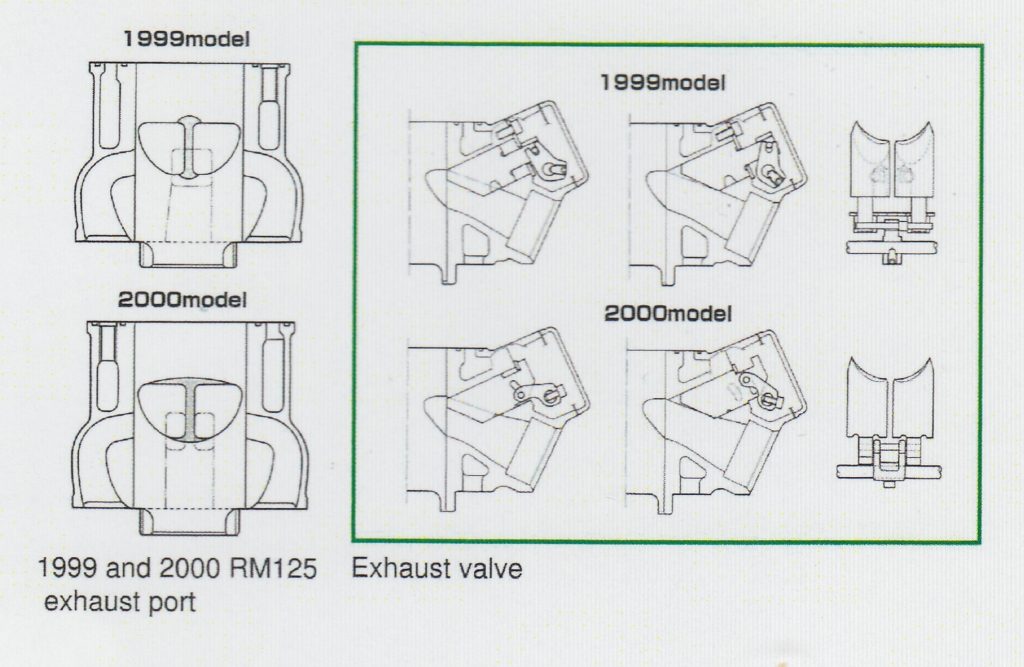

Revised porting and a redesigned exhaust valve looked to boost the RM’s modest power output for 2000. Photo Credit Suzuki

Revised porting and a redesigned exhaust valve looked to boost the RM’s modest power output for 2000. Photo Credit Suzuki

On the motor front, the RM marched into 2000 with a list of minor updates aimed at boosting its top-end pull and improving reliability. In 1999, no other 125 from Japan was close to the power output of Yamaha’s YZ125 but machines like the RM could run with the YZ by providing the right kind of power that put every one of its horses to the ground. For 2000, Suzuki aimed to keep its excellent power delivery while hopefully narrowing the three-horsepower deficit it gave up to the omnipotent Yamaha. To do that, Suzuki dialed up new porting specs that reshaped the main exhaust port and increased the surface area of the variable exhaust valves. The power valve mechanism moved to a new “L-arm” design cribbed from the RM250 to provide better sealing and a more precise engagement. The scavenging ports were reshaped for improved flow and the ring pin was moved from the front to the rear of the piston for improved sealing and a reduced chance of snagging the exhaust port. To further improve durability, the chamfering of the exhaust port ridge was modified to reduce wear on the rings and increase the life of the cylinder plating. In 1999, Suzuki coated their pistons with a “Black Floro” compound that increased piston hardness and reduced friction for improved durability.

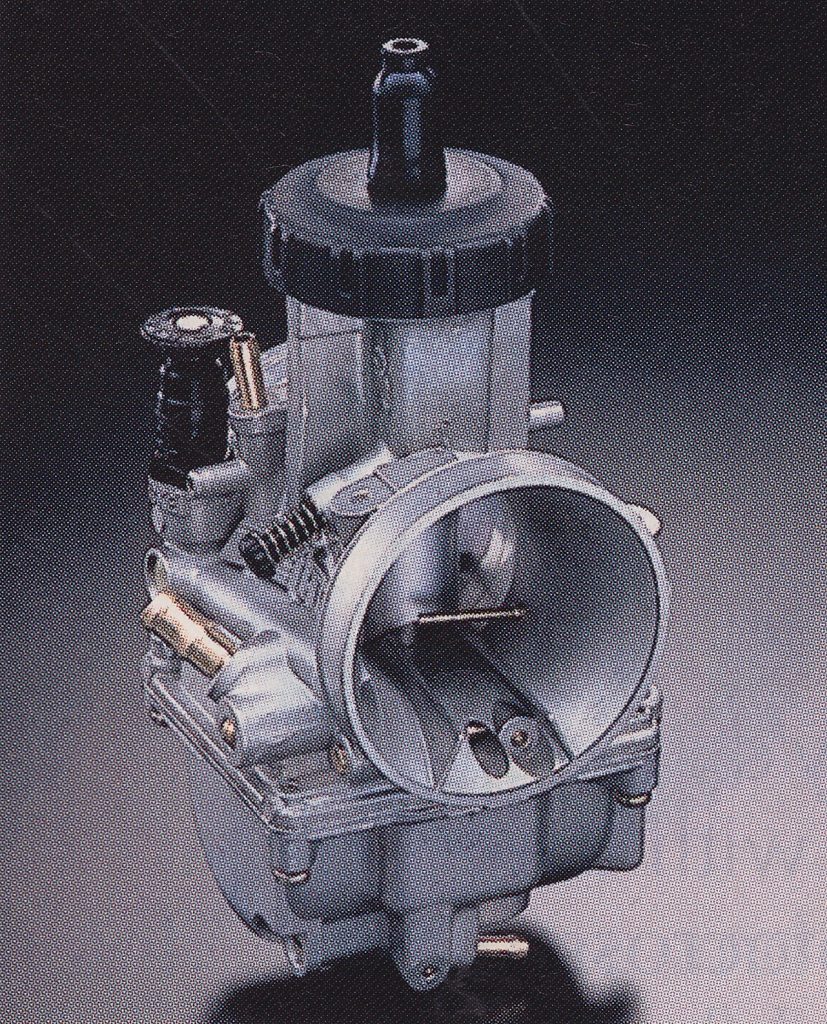

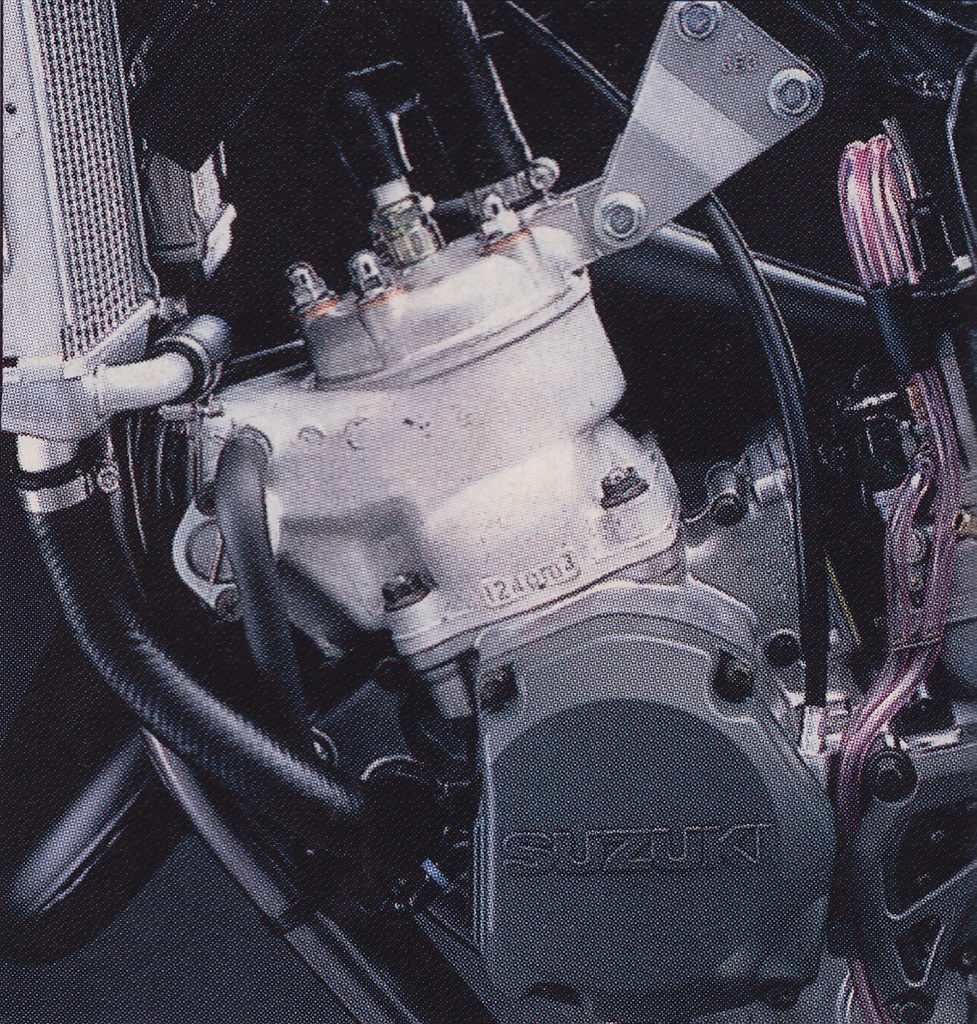

In 2000, the RM125’s 38mm Keihin mixer was one of the biggest in the class. It was the same carburetor used on the RM250 and helped give the RM125 the high-RPM power enjoyed by true 125 enthusiasts. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 2000, the RM125’s 38mm Keihin mixer was one of the biggest in the class. It was the same carburetor used on the RM250 and helped give the RM125 the high-RPM power enjoyed by true 125 enthusiasts. Photo Credit: Suzuki

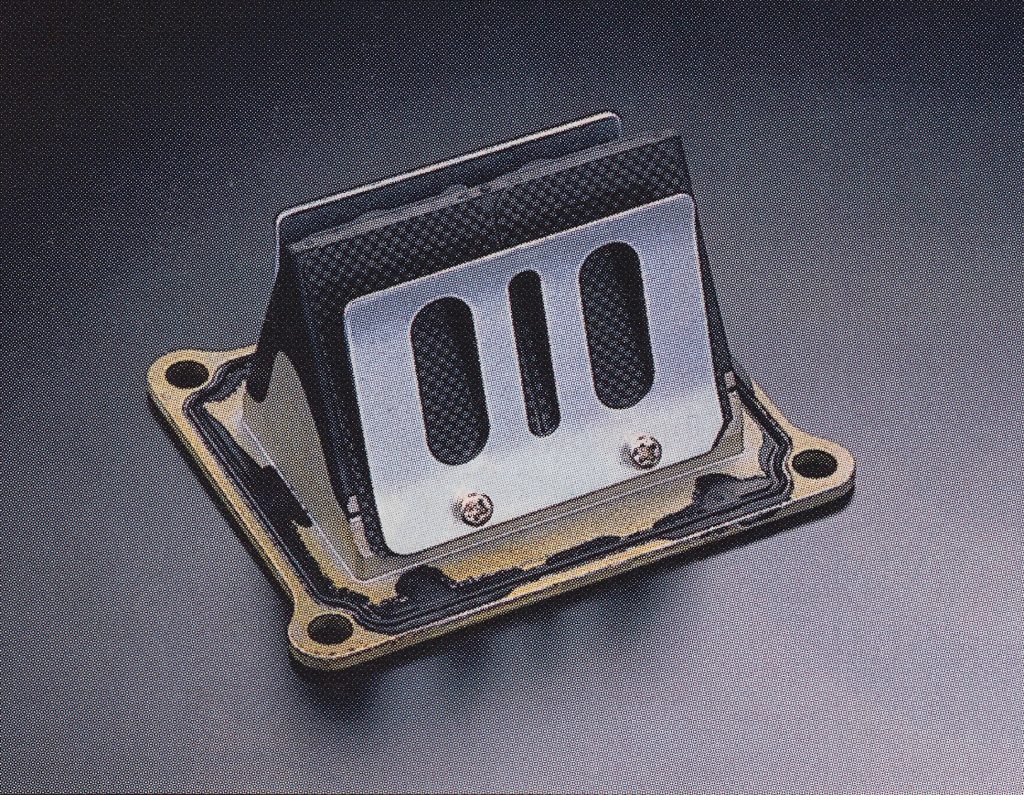

A move from resin to carbon fiber for the reeds promised improved throttle response for 2000. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A move from resin to carbon fiber for the reeds promised improved throttle response for 2000. Photo Credit: Suzuki

A new crank was spec’d for 2000 with 1.6-percent-higher inertia and a 2-percent higher primary compression to improve motor tractability and increase power. The CDI magneto was relocated inside the airbox to reduce the chance of mud or water causing a malfunction and the mapping was modified to work with the revamped porting. Transmission changes for 2000 were limited to modifications designed to make the 1999 model’s mystery neutral easier to find.

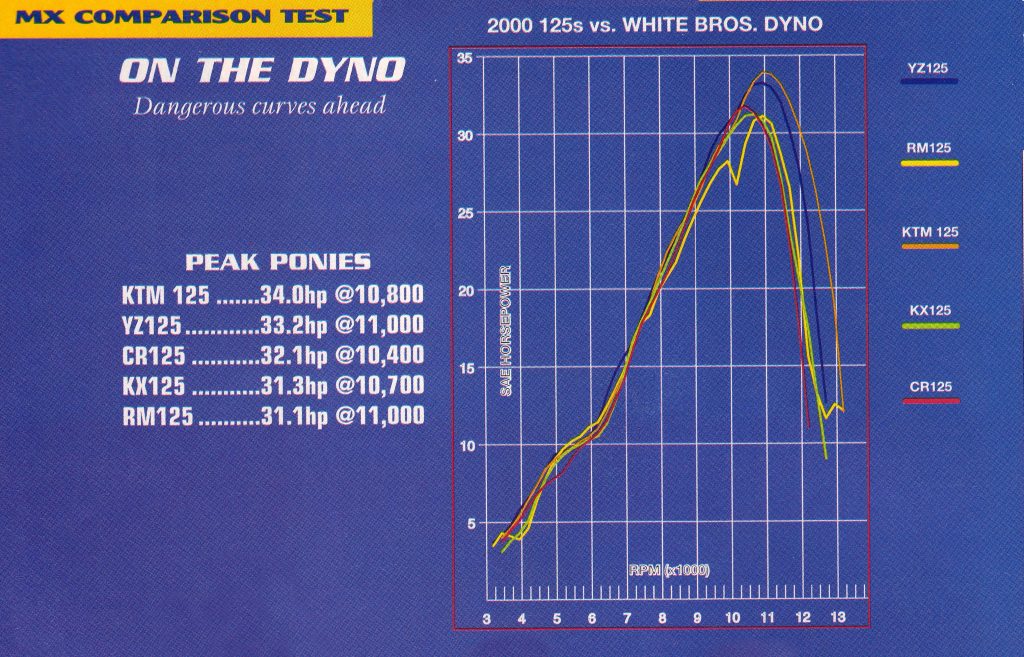

While the RM’s power was improved for 2000, it remained the 212-pound weakling of the 125 class. At its peak, it gave up nearly three horsepower to KTM’s 125SX and over two to Yamaha’s YZ125. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the RM’s power was improved for 2000, it remained the 212-pound weakling of the 125 class. At its peak, it gave up nearly three horsepower to KTM’s 125SX and over two to Yamaha’s YZ125. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the intake side, the RM continued to be fueled by Keihin’s massive 38mm PKW Power Jet mixer. This was the same carb employed on the RM250 and it provided the RM with the deep breathing necessary to keep throttle-happy 125 pilots grinning. In 2000, Suzuki added a new “bypass starter” circuit to improve low-end response and a redesigned reed valve with quicker-reacting carbon fiber reeds. Paired with the revised intake was an all-new exhaust that Suzuki claimed mimicked the shape of the 1999 factory hardware.

Despite its modest power output, the stock RM remained a very fun bike to ride. Its powerband was wide and its turning and jumping skills were unmatched. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Despite its modest power output, the stock RM remained a very fun bike to ride. Its powerband was wide and its turning and jumping skills were unmatched. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

After returning to inverted forks for 1999, the suspension changes on the RM were relatively modest for the 2000 season. The forks remained Showa’s 49mm Twin-Chamber cartridge design with stiffer springs and updated valving being the main updates for 2000. The coils were moved from 0.40 to 0.42 to increase bottoming resistance and the rebound spring was modified to improve the fork’s action at full extension.

In 2000, the biggest challenge to Suzuki’s golden boy Travis Pastrana was Yamaha of Troy’s French import Stephane Roncada. Indoors, Roncada outdueled Pastrana to the 125 East Supercross title and looked to be on his way to backing it up outdoors before a late-season charge by Pastrana snatched the title away by two points at the season finale. Photo Credit: Scott Hoffman

In 2000, the biggest challenge to Suzuki’s golden boy Travis Pastrana was Yamaha of Troy’s French import Stephane Roncada. Indoors, Roncada outdueled Pastrana to the 125 East Supercross title and looked to be on his way to backing it up outdoors before a late-season charge by Pastrana snatched the title away by two points at the season finale. Photo Credit: Scott Hoffman

In the rear, the shock was updated slightly to match the stiffer frame and beefier swingarm. The revamped shock featured revised valving and a new compression adjuster system designed to provide a less-obstructed oil flow for smoother action. A new spring was mounted that featured a slightly higher rate to fight bottoming and match the new stiffer settings up front. Lastly, new dust seals were added to the shock mounts that featured reduced friction and better sealing for smoother performance.

While the RM was less than impressive on the dyno, it was still competitive on the track. Its powerband was wide and the power that it did make was well placed. It was at its best on hard and slick tracks but if the soil was deep its lack of peak power became readily apparent. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While the RM was less than impressive on the dyno, it was still competitive on the track. Its powerband was wide and the power that it did make was well placed. It was at its best on hard and slick tracks but if the soil was deep its lack of peak power became readily apparent. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The bodywork for 2000 remained largely unchanged except for a new seat cover and updated graphics. The new graphics retained the basic design of the ’99 model with a new silver seat and honeycomb pattern in the “ROM” graphic standing as the only significant differences. While the bike’s midsection remained the slimmest in the class, the gigantic batwing radiator shrouds returned to snag boots and scoop tons of air. New footpegs for 2000 offered increased comfort by adding 6mm of width and an additional center rail for more support. New clamps increased room in the pilot’s compartment by repositioning the bars 10mm forward and new “half-waffle” grips improved comfort by smoothing out the portion of the grips that contacted the rider’s palms.

In stock condition, the 2000 RM125 was a bit of an ugly duckling but with a swap in shrouds and some updated graphics, she became a beautiful swan. Even today, Pastrana’s 2000 Factory RM125 is one great-looking motorcycle. Photo Credit: MX Racer

In stock condition, the 2000 RM125 was a bit of an ugly duckling but with a swap in shrouds and some updated graphics, she became a beautiful swan. Even today, Pastrana’s 2000 Factory RM125 is one great-looking motorcycle. Photo Credit: MX Racer

On the track, the 2000 RM125 once again proved to be a competitive if not class-leading machine. As in 1999, the Yamaha and KTM remained the powerhouses of the 125 class, and it was tough to overcome their power advantage. On the dyno, the KTM bested all comers with an output that outpaced even Yamaha’s broad and brawny YZ125. At its peak, the revamped RM gave up a 2.1 horsepower to the YZ and nearly 3 full ponies to the KTM. For many, that was all it took to knock the RM down in the final 125 standings.

After a few rough outings to start the season, Pastrana found his mojo at round four in Southwick and started his charge to the front of the 125 standings. Seconds at rounds five, six, and seven were backed up by a string of four victories in a row to close out the season and deliver the rookie his first (and only) 125 National Motocross championship. Photo Credit: Garth Milan

After a few rough outings to start the season, Pastrana found his mojo at round four in Southwick and started his charge to the front of the 125 standings. Seconds at rounds five, six, and seven were backed up by a string of four victories in a row to close out the season and deliver the rookie his first (and only) 125 National Motocross championship. Photo Credit: Garth Milan

While the RM’s power plant was not the fastest in the class, its powerband found many fans in 2000. It was responsive off idle, strong in the midrange, and pulled well on top. Much like the YZ, its powerband was quite wide and it felt like it pulled over one of the broadest ranges in the class. At no point on the curve did it have as much oomph as the YZ, but there was always some boost on tap and the RM’s powerband was very quick and flexible. On hard-packed terrain, the RM felt very fast, and it was fun and competitive in these conditions. Where things got tough for the Suzuki pilot, however, was in deep sand and heavy loam. Here, the RM’s lack of ponies became apparent, and it was easy to fall off the pipe if the shifts were not timed perfectly. Deep soil put a lot of strain on the RM’s modest output, and it was tough to keep up with the YZ and KTM in these conditions. With skill and commitment, the RM was certainly fast enough to win but its rider would need to rely on more than outright horsepower to put them at the front.

In 1999, Suzuki returned to an inverted fork design and most riders outside the pro class felt it was a step back in performance. In stock condition, the inverted 49mm Showa Twin-Chamber forks were far from the best forks in the class. They dove under braking, blew through their travel and generally moved around more than most riders were comfortable with. With some spring fiddling, oil adjustment, and clicker spinning they could be made raceable, but they were never going to outperform the best forks in the class without more extensive internal reworking. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1999, Suzuki returned to an inverted fork design and most riders outside the pro class felt it was a step back in performance. In stock condition, the inverted 49mm Showa Twin-Chamber forks were far from the best forks in the class. They dove under braking, blew through their travel and generally moved around more than most riders were comfortable with. With some spring fiddling, oil adjustment, and clicker spinning they could be made raceable, but they were never going to outperform the best forks in the class without more extensive internal reworking. Photo Credit: Suzuki

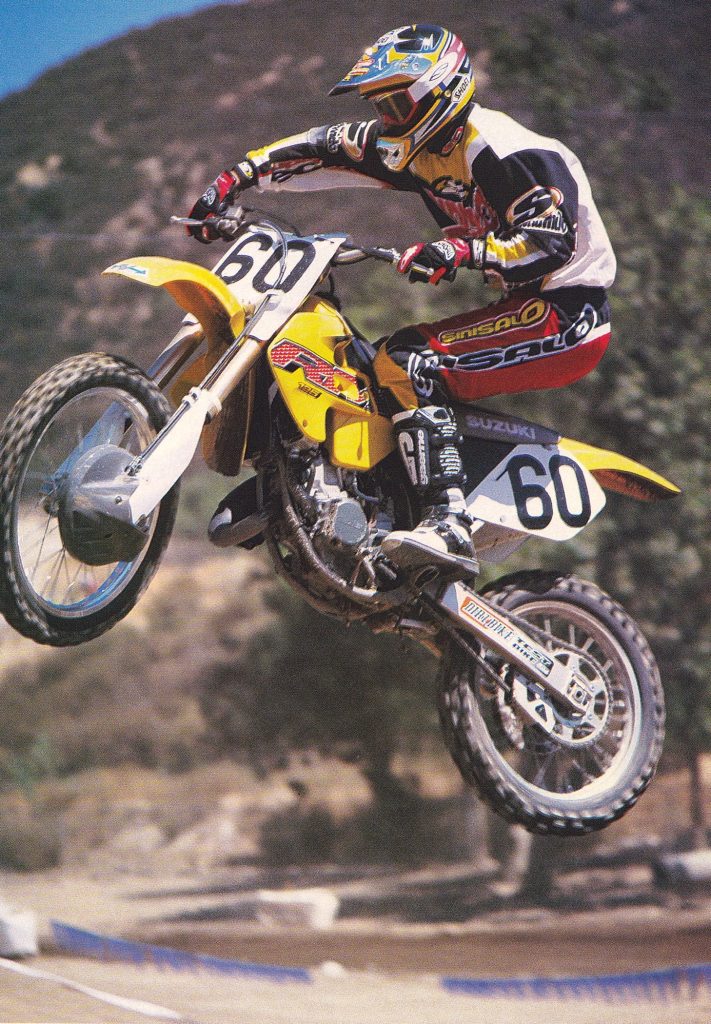

For most riders, the RM’s biggest advantage was its handling. On tight tracks, the RM had no peer and it loved to slice under its rivals when the course got twisty. Front-end traction was excellent and there was never a fear that the front wheel would wash out or do anything unexpected. Jumping was also a Suzuki strong suit with the RM’s snappy power and excellent ergonomics giving it a feathery feel in the air. It was easy to place the RM exactly where you wanted it and easy to whip it back into shape if things got a bit off course. Shredding corners and launching off doubles was an absolute blast on the RM and riders of all skill levels loved its light and airy feel.

While the internal motor modifications for the 2000 season did yield improved top-end life, the RM’s motor continued to be disappointingly fragile. Crank reliability was quite suspect, and it was important to run high-quality oil and keep a close eye on internal clearances if you hoped to keep your $5000 investment on the track. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While the internal motor modifications for the 2000 season did yield improved top-end life, the RM’s motor continued to be disappointingly fragile. Crank reliability was quite suspect, and it was important to run high-quality oil and keep a close eye on internal clearances if you hoped to keep your $5000 investment on the track. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While the RM was a terror in the turns, it often elicited more than a bit of terror of its own at speed. High-speed stability remained elusive, and the RM could be a bit disconcerting once the track opened up. Once out of the twisties, the RM suffered from a busy feel that unsettled riders unaccustomed to the Suzuki’s aggressive geometry. Longtime RM pilots barely noticed the Suzuki’s wandering but riders jumping off the Yamaha and Kawasaki found its loosey-goosey feel unsettling.

Shock performance on the 2000 RM125 was only slightly better than the stock forks. Most riders felt it could be raced in stock condition, but the action was busy in the rough and not particularly plush. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Shock performance on the 2000 RM125 was only slightly better than the stock forks. Most riders felt it could be raced in stock condition, but the action was busy in the rough and not particularly plush. Photo Credit: Suzuki

On the suspension front, the RM was once again a middle-of-the-pack performer. The updated settings for 2000 provided a bit more control than in 1999 and the forks were less prone to bottoming, but riders still complained that the action was very busy. There was a noticeable amount of dive under braking and the forks felt underdamped on braking bumps and small chop. The forks never quite felt settled, and this certainly played a role in the RM’s hyperactive feel at speed. Most riders felt the forks could be raced with some fine-tuning of the clickers, but they were never going to perform as well as the front ends of its Japanese rivals without a spring swap and revalve.

Going big and getting loose were the RM’s strong suit in 2000. Its compact ergos, slim midsection, and feathery feel made the Suzuki the ideal partner for Pastrana-style antics on and off the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Going big and getting loose were the RM’s strong suit in 2000. Its compact ergos, slim midsection, and feathery feel made the Suzuki the ideal partner for Pastrana-style antics on and off the track. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the rear, the story was very much the same with the RM continuing to deliver middling performance. Once again, the biggest complaint was its busy feel that never seemed to settle down and let the RM follow the track. It was hacky in the breaking bumps and blew through the stroke on hard hits. Many riders blamed the RM’s new progressive rate spring which seemed to be flummoxed by both small chop and large leaps. Going with a stiffer straight-rate spring helped considerably but the RM’s shock remained less well controlled than the shocks found on the Honda and Yamaha 125.

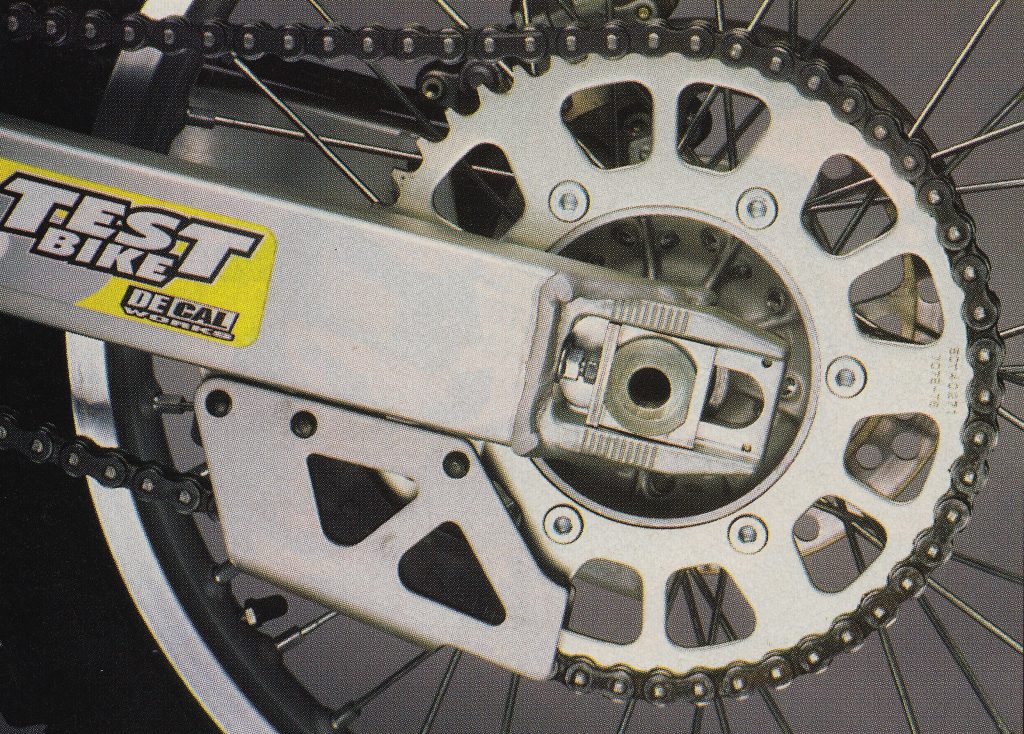

Adding a tooth or two to the rear sprocket was the best way to keep the RM’s motor singing in 2000. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Adding a tooth or two to the rear sprocket was the best way to keep the RM’s motor singing in 2000. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the detailing front, the RM was a significant step behind the best machines in the class in 2000. While most riders were not sad to see them go, the lack of durability of the stock graphics was rather alarming to many who just shelled out their hard-earned $5000 for a new 125. The quality of the stock bars, graphics, fasteners, chain, and switchgear was all disappointing. Just looking sideways at the bars was enough to bend them and levers began rattling shortly after break-in. The stock chain and sprockets were made of recycled butter and best used as a paperweight or bit of garage decoration. While replacing the stock pot metal components, it was a good idea to add a tooth or two to the rear sprocket to punch up the motor’s modest oomph. The RM’s motor sounded beat even when new due to the excessive amount of clatter it produced. While this did not affect power, it did contribute to the generally worn-out feel the bike had compared to the Honda, Yamaha, and KTM. While the engine sounded rattly, the motor changes for 2000 did improve reliability with fewer snagged rings and improved cylinder life over the year before. The clutch was buttery smooth in action but perpetually on the verge of slipping if hammered. The shifting feel was excellent but finding neutral remained elusive with the engine running. The braking feel was improved for 2000 with the rear feeling less grabby and both ends offering excellent power. Riders loved the new wider pegs and slightly more roomy riding compartment, but the RM remained a bit cramped for Travis Pastrana-sized pilots. A taller seat and bars were the easiest fix for the Big Bird set.

Pastrana capped off his incredible 2000 motocross season by helping to bring Team USA its first Motocross des Nations title in four years at St. Angely in France. Photo Credit: Jim Sanderson

Pastrana capped off his incredible 2000 motocross season by helping to bring Team USA its first Motocross des Nations title in four years at St. Angely in France. Photo Credit: Jim Sanderson

Overall, the 2000 RM125 proved to be a fun but flawed racing package. If the conditions were right, the Suzuki had a fighting chance against its rivals but in stock condition, it gave up a significant amount of power and suspension finesse to its rivals. If the track was tight and hard the RM could fly but throw in some deep sand and a few long hills and the task got exponentially harder. Despite its lack of tire-shredding horsepower, the RM still had a lot of loyal devotees who enjoyed its feathery feel, razor-sharp handling, and snappy powerband. Any way you sliced it, the RM was a fun and engaging bike to ride, and with a little massaging, it had the performance to win at the national level indoors and out.

In 2000, there were faster and better-suspended 125s available, but nothing in the class handled and felt like Suzuki’s RM125. As long as you favored finesse over outright firepower, the RM was a fun and capable racing partner. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

In 2000, there were faster and better-suspended 125s available, but nothing in the class handled and felt like Suzuki’s RM125. As long as you favored finesse over outright firepower, the RM was a fun and capable racing partner. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider