For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at KTM’s 2001 125SX.

All-new bodywork and a redesigned motor made KTM’s rocket-fast tiddler a legitimate 125 contender in 2001. Photo Credit: KTM

All-new bodywork and a redesigned motor made KTM’s rocket-fast tiddler a legitimate 125 contender in 2001. Photo Credit: KTM

The 1990s were an up-and-down decade for Austria’s KTM. Bankruptcy in the early 1990s nearly sank the brand, but the resulting restructuring gave KTM new life in the marketplace.

The Austrians came back stronger than ever with unique products and a strategy of hitting the Japanese where they weren’t. Mid-sized Open bikes, thundering four-strokes, and a cornucopia of off-road entries helped bring the troubled brand back from the brink of extinction. By diversifying their lineup and focusing on being more agile than the conservative Japanese, KTM was able to carve out a niche of success in the latter part of the decade.

KTM’s 125 fortunes took a major turn for the better in 1998 with the introduction of their totally redesigned 125SX. All-new from the ground up, it featured high-quality components and an unconventional suspension design to set it apart from

KTM’s 125 fortunes took a major turn for the better in 1998 with the introduction of their totally redesigned 125SX. All-new from the ground up, it featured high-quality components and an unconventional suspension design to set it apart from

the ubiquitous Japanese. Photo Credit: KTM

In 1998, KTM took its biggest swing yet by introducing a lineup of all-new machines that broke with traditional chassis and suspension design. Redesigned from the ground up, the 1998 KTMs removed the rising rate linkages in use since 1982 and replaced them with a “no-link” design that allowed the engineers to save weight, simplify servicing, and improve airflow to the motors. All-new bodywork offered slim lines, attractive styling, and an end to the oddball squash pie hues of 1996 and 1997.

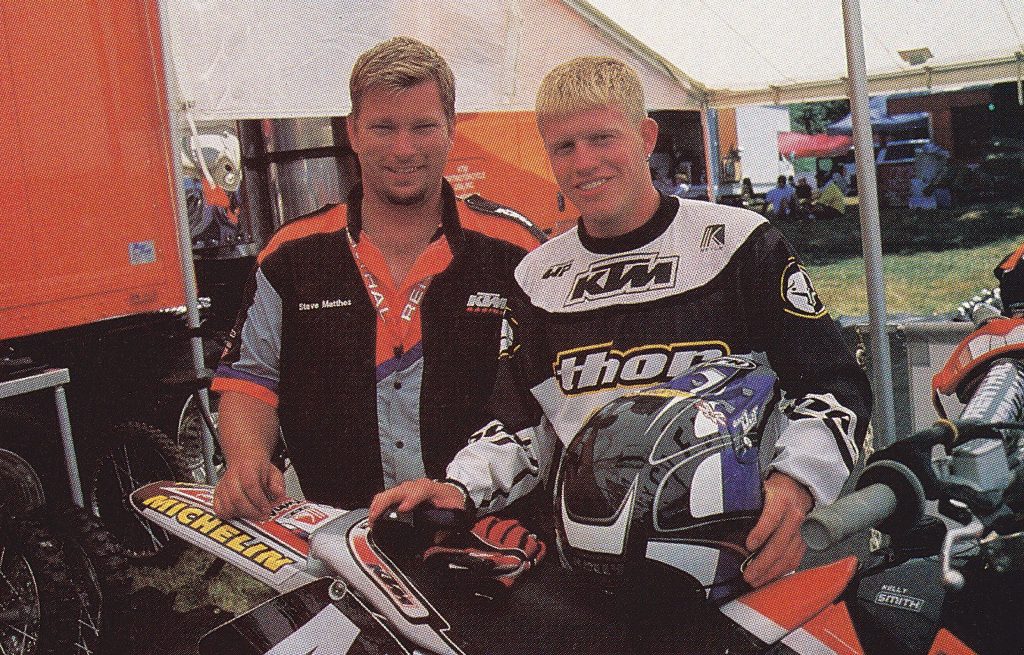

In 2000, Steve Matthes and Kelly Smith delivered KTM their first major US win with a victory at High Point.

In 2000, Steve Matthes and Kelly Smith delivered KTM their first major US win with a victory at High Point.

Of all the machines in KTM’s lineup, the one most in need of a major reboot was the 125SX. New bodywork in 1993 refreshed the 125 Katoom’s styling, but the basic 125SX package could trace its roots back to the late eighties. By 1997, none of the major magazines were even bothering to test the 125SX or include the outdated machine in their annual 125 shootouts. It was obvious that the 125SX was not a priority to KTM and this was reflected in its near invisibility in the enthusiast press.

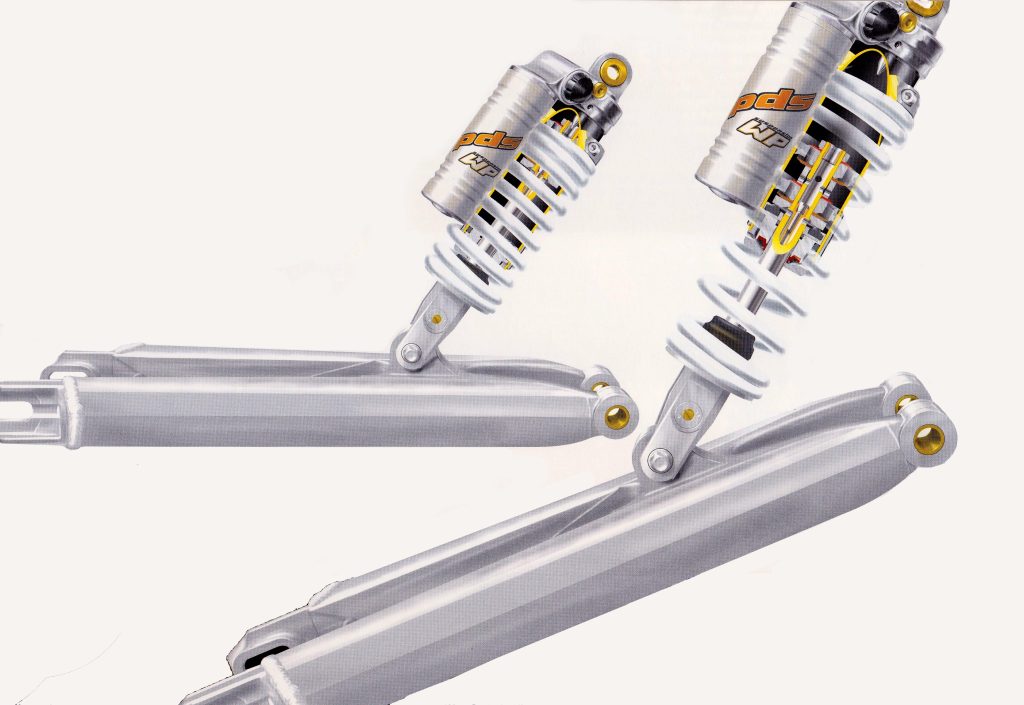

In 1998, KTM moved to an all-new linkless rear suspension design that they believed offered substantial advantages over the traditional rising rate linkages in use since the early eighties. The new PDS (Progressive Damping System) was lighter, simpler to service, and offered packaging advantages that provided better airflow to the motor. Photo Credit: KTM

In 1998, KTM moved to an all-new linkless rear suspension design that they believed offered substantial advantages over the traditional rising rate linkages in use since the early eighties. The new PDS (Progressive Damping System) was lighter, simpler to service, and offered packaging advantages that provided better airflow to the motor. Photo Credit: KTM

In 1998, all of this changed with the introduction of KTM’s redesigned no-link 125SX. The new machine was an absolute rocket with tons of top-end power and a much-improved layout. The redesigned ergonomics were slim and comfortable, and the bike was awash with trick features and high-quality components. Its hydraulic clutch was works bike trick and its no-link rear suspension made servicing the air filter and shock a breeze. Most riders liked the old-school Marzocchi conventional forks but not everyone could come to terms with the feel of the WP PDS (Progressive Damping System) shock. Overall, it was still a tick behind the Japanese, but for the first time since the days of Penton, the Austrians were a legitimate contender in the 125 division.

In 2001, 125s were still the hottest-selling segment in the sport but the arrival of Yamaha’s all-new YZ250F would prove to be the first of many four-stroke nails in the 125’s competitive coffin. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 2001, 125s were still the hottest-selling segment in the sport but the arrival of Yamaha’s all-new YZ250F would prove to be the first of many four-stroke nails in the 125’s competitive coffin. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

By the 2000 season, KTM’s 125SX was firmly entrenched as a threat to the domination of the Japanese in the 125 division. The 125SX’s 124.8cc case-reed mill pumped out the most peak power in the class and delivered it to the ground with the buttery smooth action of its hydraulic clutch. This season saw KTM finally abandon the conventional fork fight with the retirement of WP’s well-regarded 50mm Extreme silverware. In their place, KTM bolted on a new 43mm inverted WP design. In the rear, the 2000 125SX continued to use WP’s no-link PDS damper to moderate success. While raceable, most riders felt that the KTM’s stock suspension was still its biggest handicap against the Japanese. It worked well off-road but delivered a different feel on the track that not everyone was comfortable with. The new forks were not as well-liked as the old conventional units and the shock’s unique feel continued to prove polarizing. Handing was decent, but the KTM was more adequate than impressive in this regard. The relationship of the seat, tank, pegs, and bars still struck some as “Euro” and the KTM never felt as glued to the track as handling standouts like the RM and CR. Overall, it was a very competitive package despite its disappointing suspension. No other 125 could outduel it in a test of pure speed and in the 125 class that tended to cover up a mountain of other sins.

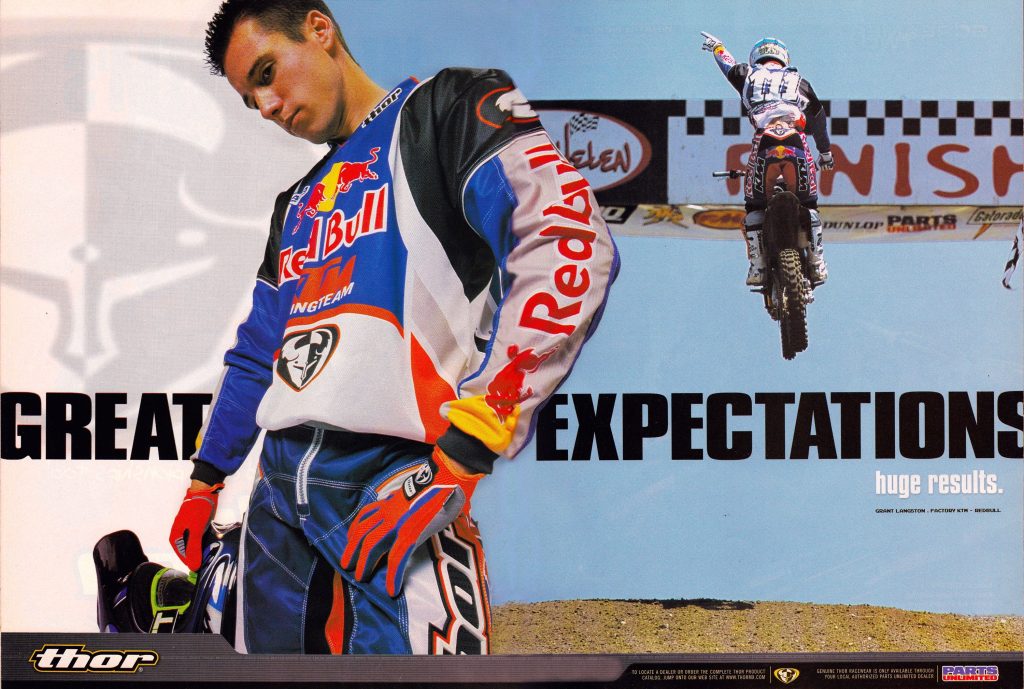

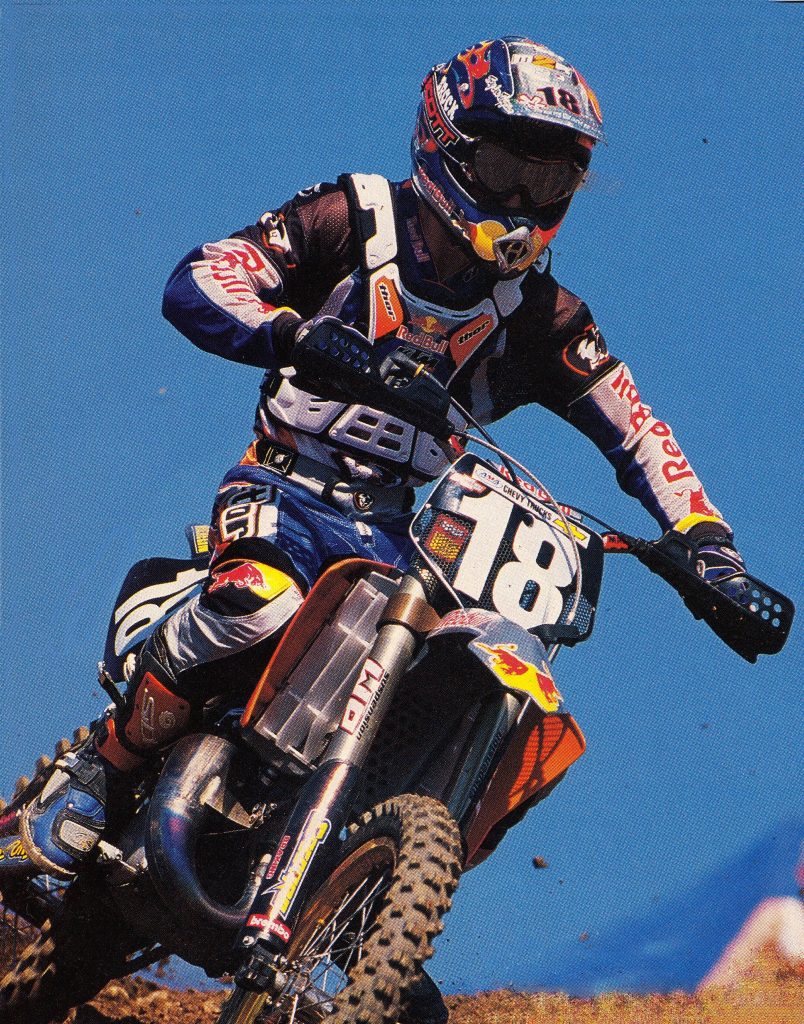

The Zulu Warrior: After several decades of flirting with the US racing market, KTM finally got serious about putting forth a legitimate championship effort in 2001. The arrival of 2000 World Motocross champion Grant Langston immediately upgraded the team’s expectations and results. Photo Credit: Thor

The Zulu Warrior: After several decades of flirting with the US racing market, KTM finally got serious about putting forth a legitimate championship effort in 2001. The arrival of 2000 World Motocross champion Grant Langston immediately upgraded the team’s expectations and results. Photo Credit: Thor

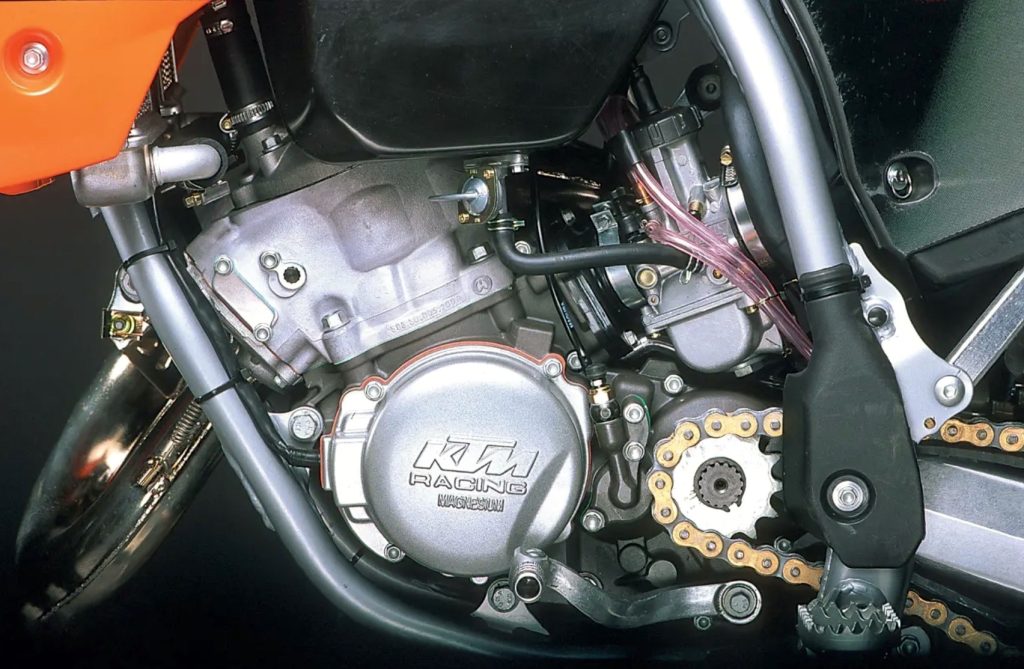

For 2001, KTM’s goal for its 125 was to broaden its already impressive power, refine its controversial suspension, and bring its ergonomics more in line with its Japanese rivals. To accomplish these goals KTM dialed up a list of significant changes for 2001. First up was an all-new engine that borrowed heavily from the experience the factory team in Europe had gained on the way to winning the 2000 125 World Motocross Championship. The new motor mimicked the bore and stroke of Grant Langston and Jamie Dobb’s 2000 works machines and moved the 125SX to a more under-square 54mm x 54.5mm configuration. The new cylinder featured revised porting and a lightened single-ring piston. A new crank was lighter and slightly wider to increase crankcase pressure and allow the motor to spin up more freely. Carburetion duties remained the responsibility of Keihin’s massive 39mm PKW mixer. This deep breather was the same unit found on Kawasaki’s KX500 and certainly played a part in the KTM’s shrieking top-end performance. A new shifter was added with a 12mm longer shaft and a 6mm larger offset. This was done to provide more room for the rider’s boot and deliver a more positive shifting feel.

An all-new seat and tank for 2001 slimmed the bike’s midsection, flattened the riding position, and lowered the fuel placement to improve comfort and handling. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

An all-new seat and tank for 2001 slimmed the bike’s midsection, flattened the riding position, and lowered the fuel placement to improve comfort and handling. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

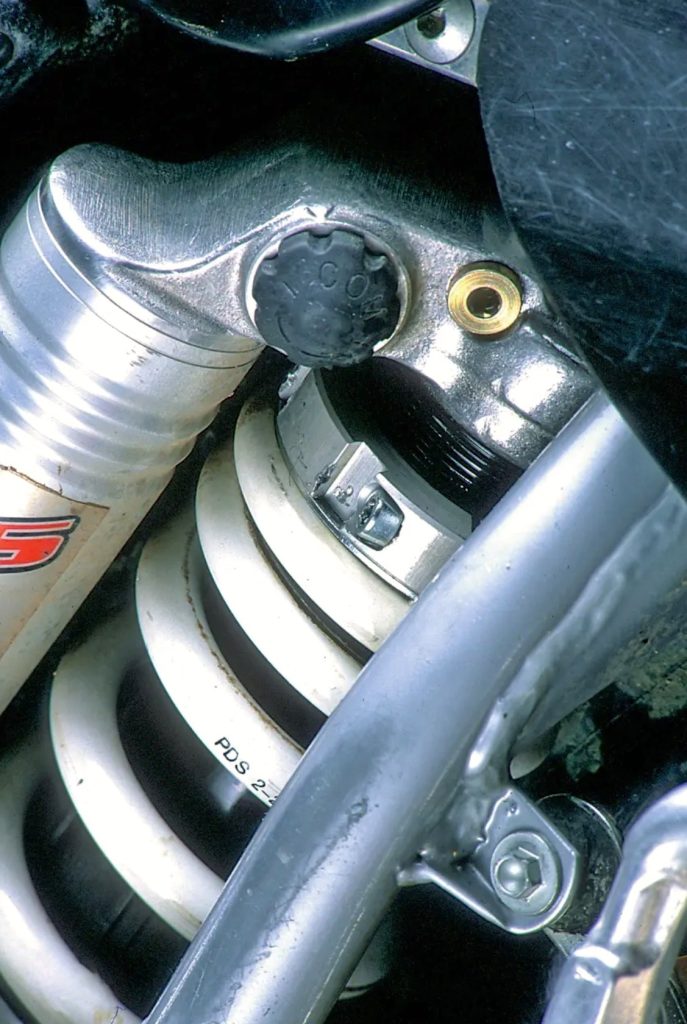

On the chassis front, the 125SX was largely a carryover from the year before. The frame was unchanged and continued to eschew the rising rate linkages of the Japanese. By eliminating the linkage, the Austrians were able to move the shock to the side and place the airbox and air intake in the optimal position to provide unobstructed airflow into the motor. The no-link design also provided easier access to the shock and eliminated the annoying task of servicing and greasing the linkage. As before, KTM relied on WP’s PDS “smart shock” to compensate for the lack of a rising rate linkage. The PDS design relied on careful shock placement and a pair of pistons within the shock to react to varied track conditions and provide small bump compliance and hard-hit resistance. An all-new swingarm for 2001 featured a “one piece” construction that offered increased strength through the elimination of any welds. For 2001, WP revised the damping of the PDS shock and replaced the rebound valve with a needle to reduce the thermal load on the piston and provide a more consistent damping response. Shock travel was set at 13.4 inches with external adjustments available for high and low-speed compression as well as rebound damping.

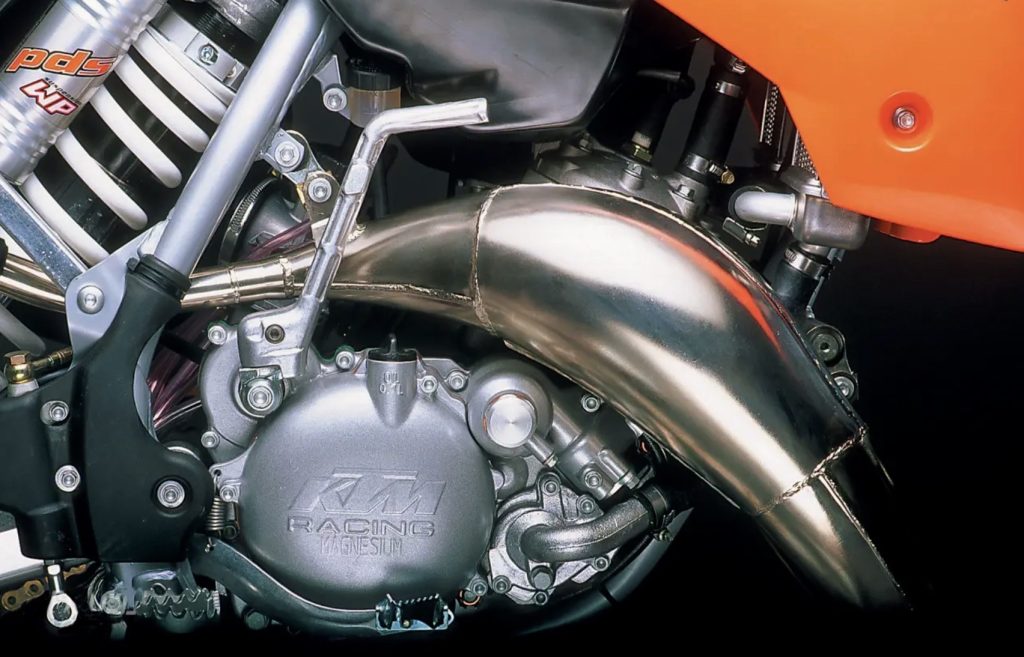

An all-new motor for 2001 extended the stroke .5mm, reshaped the ports, lightened the crank, and increased its diameter to up primary compression. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

An all-new motor for 2001 extended the stroke .5mm, reshaped the ports, lightened the crank, and increased its diameter to up primary compression. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Up front, the 125SX continued to employ WP’s 43mm Multi Adjuster inverted forks. Changes for 2001 included stiffer damping settings and a 1.5mm increase in the diameter of the cartridge rod. The spring rates remained unchanged featuring the same 0.38kg/mm coils found in 2000. Overall travel was set at 11.8 inches with external adjustments available for compression and rebound damping.

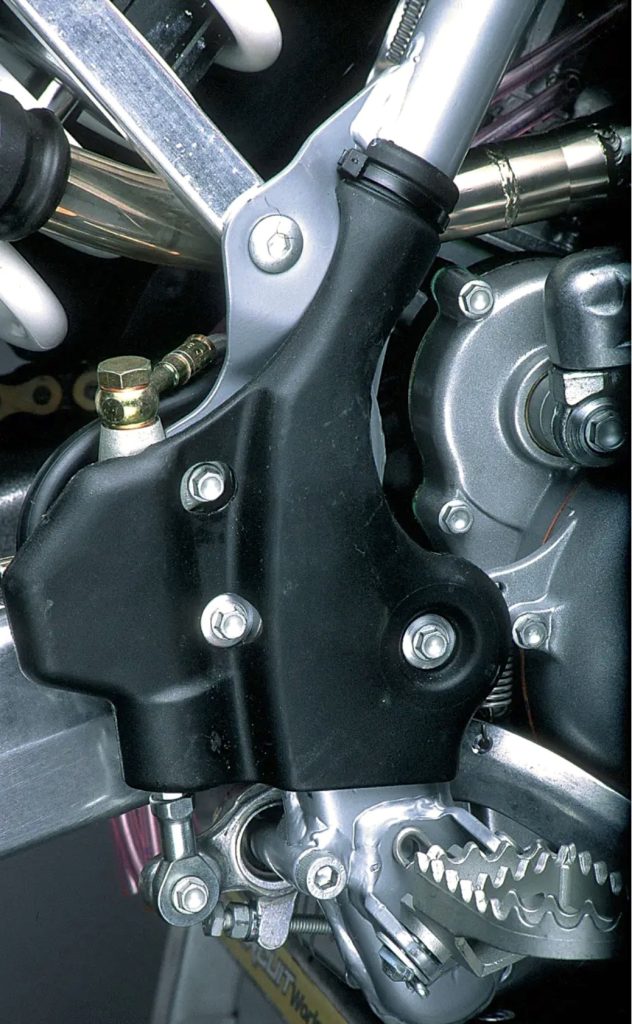

An all-new rear brake for 2001 improved feel and did away with most of the 2000 model’s grabby engagement. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

An all-new rear brake for 2001 improved feel and did away with most of the 2000 model’s grabby engagement. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

One of the major complaints riders had voiced over the years with KTM’s machines was their unique ergonomic feel. Oversized controls, concrete seats, and very different bar/seat/peg relationships often made European machines a hard sell to racers raised on the ubiquitous Japanese machines. In 1998, KTM made major strides in this area, but many riders still felt the Austrians felt more like off-roaders than svelte motocross racers.

After throwing away the win with a last-lap crash in Houston, Grant Langston finally delivered KTM its long-sought first Supercross victory with a resounding win at round two in Dallas. Photo Credit: TWMX

After throwing away the win with a last-lap crash in Houston, Grant Langston finally delivered KTM its long-sought first Supercross victory with a resounding win at round two in Dallas. Photo Credit: TWMX

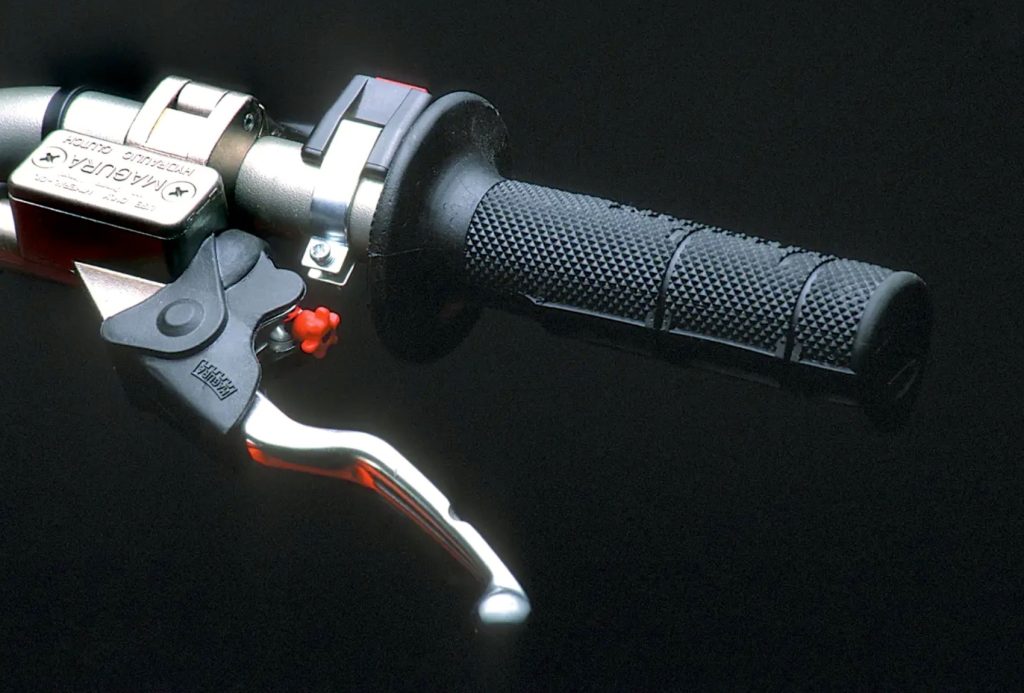

For 2001, KTM looked to eliminate the “Euro feel” stigma by redesigning the pilot’s compartment on the 125SX. The front and rear fenders, side plates, and front number plate were carryovers from 2000, but the tank, shrouds, and seat were all-new for 2001. The new tank was lower, slimmer, and sleeker than in the past giving the bike a whole new feel. The new seat was flatter on top, lower at the front, longer overall, and covered with a new “non-slip” material designed to keep the rider in place under acceleration. The new shrouds were smaller overall and featured a trick embossed graphic instead of traditional decals. An all-new Magura “Fat Bar” was added that featured a taller and straighter bend designed to suit the new more forward riding position. The awesome hydraulic clutch remained and was paired with a redesigned front brake with a shorter lever and revised leverage ratio. Race-proven Brembo components were featured front and rear with a smaller rear caliper added to improve the braking feel and reduce the chance of an unwanted stall.

High-quality Magura controls, comfortable half-waffle grips, 4-position reversible bar mounts, and a trick oversized alloy handlebar made the KTM feel premium in 2001. Photo Credit: KTM

High-quality Magura controls, comfortable half-waffle grips, 4-position reversible bar mounts, and a trick oversized alloy handlebar made the KTM feel premium in 2001. Photo Credit: KTM

Big power made the KTM a real blast to ride in 2001. Shredding berms were easy work and KTM was one of the few 125s with the cajones to go head-to-head with Yamaha’s 250F cheater and not come away eating roost. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Big power made the KTM a real blast to ride in 2001. Shredding berms were easy work and KTM was one of the few 125s with the cajones to go head-to-head with Yamaha’s 250F cheater and not come away eating roost. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

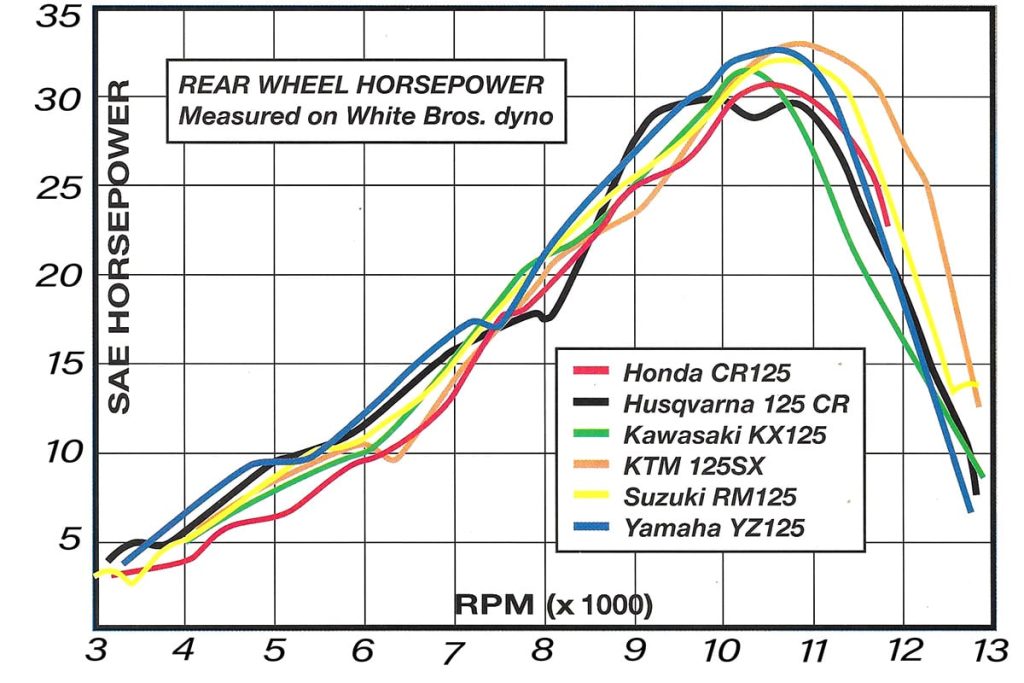

On the track, the 2001 KTM 125SX remained the rocket of the 125 class. It produced the most peak horsepower and did so at the highest RPM. At its peak, it outpaced its nearest rival by nearly two horsepower and buried machines like the RM125 by over five horsepower in the midrange. As before, its low-end power was not particularly impressive and KTM wasted no time chasing the “do-it-all” powerband of Yamaha’s YZ125. Instead, the Austrians went all-in on the style of power that made 125s the favorite of Rev Rangers everywhere. From the midrange on up was where the KTM did its best work and once it caught fire it was a hypersonic missile. The new motor boosted midrange slightly and it pulled a little cleaner down low, but for the most part, it ran the same as the year before. The hydraulic clutch worked excellently and gave the lever a super light pull that never varied in the heat of battle. Novices to pros loved the KTM’s motor and nearly everyone agreed that it was by far the best 125 racing engine of 2001.

In 2001, no other 125 was as potent as KTM’s case-reed powerhouse. Broad, powerful, and blessed with nearly endless rev, it was the ultimate 125 racing engine. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 2001, no other 125 was as potent as KTM’s case-reed powerhouse. Broad, powerful, and blessed with nearly endless rev, it was the ultimate 125 racing engine. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Unfortunately, however, it takes more than a fast motor to win a motocross race and here the KTM suffered against its rivals. The new ergonomics were a significant improvement with the 125SX offering the slimmest midsection in the class. Riders loved the slim tank, trick alloy bars, and four-position adjustable clamps but continued to pan the rock-hard seat and long and spread-out feel of the rider compartment. The bar/seat/peg relationship continued to seem foreign to riders jumping off the more compact Japanese machines, but this went away with a bit of time in the saddle. What did not go away, however, was the KTM’s slightly wayward handling.

Once the motocross wagon train hit the great outdoors it was quite apparent that Grant Langston and KTM were a legitimate threat for the 125 National Motocross title. Double moto wins at rounds one and two were backed up with wins at Unadilla, Spring Creek, and Broom-Tioga. If not for an unfortunate mechanical failure in the season finale Langston would have brought KTM their first 125 National Motocross title in 2001. Photo Credit: Garth Milan

Once the motocross wagon train hit the great outdoors it was quite apparent that Grant Langston and KTM were a legitimate threat for the 125 National Motocross title. Double moto wins at rounds one and two were backed up with wins at Unadilla, Spring Creek, and Broom-Tioga. If not for an unfortunate mechanical failure in the season finale Langston would have brought KTM their first 125 National Motocross title in 2001. Photo Credit: Garth Milan

A fragile wheel and a few broken spokes were all it took to torpedo a dream season for Langston and KTM. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

A fragile wheel and a few broken spokes were all it took to torpedo a dream season for Langston and KTM. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

The 125SX was very light and slim and generally fun to ride but its chassis could sometimes be unpredictable. The KTM’s turning was decent but it never imparted the same level of precision as the best of the Japanese. There was a push to the front end on hard pack and the bike never fully felt planted in the rough. At speed, the 125 Katoom was known to break out into violent headshake from time to time and generally wander more than many riders were comfortable with. Several testers found it hard to trust the KTM as it often reacted in different manners to the same input. Even riders accustomed to the KTM’s unique feel found this unpredictability disconcerting. Being an ultralight 125, it was far from a dump truck on the track, but when ridden back-to-back, it was clear that the KTM’s handing was a step behind its Big Four rivals in 2001.

Riders like Brock Sellards could make the 125SX shred, but its stock handling was not the sharpest and most predictable in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Simon Cudby

Riders like Brock Sellards could make the 125SX shred, but its stock handling was not the sharpest and most predictable in the 125 class. Photo Credit: Simon Cudby

In the minds of many, most of that unpredictability could be chalked up to the KTM’s unique chassis and suspension design. On paper, KTM claimed that the PDS should work just as well if not better than the linkage-equipped machines of the Japanese. Careful shock placement and the advanced damping capability of the PDS design were designed to mimic the benefits of a linkage without the drawbacks of its complicated and heavy construction. While this sounded great in KTM’s ad copy, it never really translated 100% to the track. Off-road riders praised the slower and less “live” action of the PDS damper, but many motocross guys never warmed to its unique feel. There was less “pop” when trying to clear obstacles and a dead feel when pounding whoops. Odd hops and sudden swaps were a PDS hallmark, and this contributed greatly to the KTM’s low marks for overall handling.

Singing the high note: White Brother’s dyno told the tail of the tape in 2001. No other 125 pulled as hard or as far on top as KTM’s shrieking 125SX.

Singing the high note: White Brother’s dyno told the tail of the tape in 2001. No other 125 pulled as hard or as far on top as KTM’s shrieking 125SX.

While the 125SX was more than fast enough to win, its suspension was not always up to the task. The PDS damper was confused in action and often unpredictable on the track. Some riders appreciated its unique feel, but most seemed to feel its action was the biggest handicap to the KTM’s aspirations of 125 dominance. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the 125SX was more than fast enough to win, its suspension was not always up to the task. The PDS damper was confused in action and often unpredictable on the track. Some riders appreciated its unique feel, but most seemed to feel its action was the biggest handicap to the KTM’s aspirations of 125 dominance. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In terms of pure bump absorption, the KTM’s stock suspension components were mediocre performers in 2001. The PDS damper was praised by a few but mostly panned by the majority of others. There seemed to be very little consensus as to its performance aside from its inconsistent action. Some riders felt the shock was too stiff while others found it to be too soft. On small stuff, the shock felt uncompliant, but it still bottomed harshly on big hits. It was often prone to kicking on braking bumps and generally felt unsettled in the rough. This weird combination of too hard and too soft proved quite unpopular and most riders rated the PDS as the worst rear suspension in the 2001 125 class.

While more conventional than the PDS rear suspension, the KTM’s WP front forks proved no more successful at winning proponents on the track. Harsh, undersprung, and punishing in the rough, these forks were the least loved of the silverware choices in 2001. Photo Credit: KTM

While more conventional than the PDS rear suspension, the KTM’s WP front forks proved no more successful at winning proponents on the track. Harsh, undersprung, and punishing in the rough, these forks were the least loved of the silverware choices in 2001. Photo Credit: KTM

Easy access: While the PDS damper’s compression knob made setting changes easy, its placement on the shock body made accidental mid-moto adjustments common. Many riders felt a flat-head screw was a better choice to prevent unintentional knob spinning. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Easy access: While the PDS damper’s compression knob made setting changes easy, its placement on the shock body made accidental mid-moto adjustments common. Many riders felt a flat-head screw was a better choice to prevent unintentional knob spinning. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Up front, the outlook was no better with the 43mm WP forks receiving a unanimous thumbs down from the magazine testers. In stock condition, the forks were harsh and prone to bottoming. They blew through their stroke on jump faces and crashed to the stops with a clank on major sky shots. Despite their soft settings, they were not particularly plush on the small chop and generally pounded the pilot’s wrists to a pulp if the track was rough. Dialing up the compression and upping the spring rate helped but the WP components were never going to be in the same league as the excellent forks offered by the Japanese in 2001.

Even today, the 2001 KTM’s trick Magura hydraulic clutch is a feature not found on every motocross machine. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Even today, the 2001 KTM’s trick Magura hydraulic clutch is a feature not found on every motocross machine. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the detailing front, the KTM was a step above its rivals in 2001. The oversized aluminum bars, tough chain, and durable sprockets were all a quantum leap above the cheap pot metal components found on most of the Japanese bikes in 2001. The embossed graphics, Excel rims, Brembo brakes, toolless air filter access, hydraulic clutch, nickel-plated exhaust, and high-quality switchgear all spoke to KTM’s desire to set itself apart as a premium product. Everything you touched, looked at, or worked on felt high quality, and that helped justify its slightly higher $5098 cost. Not everyone loved the quirky orange/silver color combo and rock-hard stock seat, but for the most part, the KTM was a very well-built and excellently finished product.

Ohio’s Brock Sellards backed up Langston all season on his way to 5th overall in the 2001 125 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Simon Cudby

Ohio’s Brock Sellards backed up Langston all season on his way to 5th overall in the 2001 125 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Simon Cudby

In the end, the 2001 KTM 125SX was a very capable but slightly flawed racing machine. In the 125 class, a wickedly fast motor is often said to trump all other deficiencies, but many riders felt the KTM’s suspension and handling quirks were too hard to overlook in 2001. Despite its substantial power advantage, very few testers picked the KTM as the best stock 125 racer available that year. What was clear, however, was that the 125SX had what it took to win once its stock suspension was sorted. Riders like David Pingree, Brock Sellards, Kelly Smith, and Grant Langston put their KTMs at the front in 2001 and it was readily apparent that the Austrians were no longer content to play second fiddle to the Japanese in America. The 2001 KTM 125SX was not quite ready to unseat Japan’s top contenders, but that gap was no longer a gulf.

Slick, trick, and wickedly fast, KTM’s 2001 125SX was a rocket ship in need of a chassis overhaul. With better suspension and a bit of fine-tuning, it was a world-class winner, but in stock condition, there were easier paths to the victory circle in 2001. Photo Credit: KTM

Slick, trick, and wickedly fast, KTM’s 2001 125SX was a rocket ship in need of a chassis overhaul. With better suspension and a bit of fine-tuning, it was a world-class winner, but in stock condition, there were easier paths to the victory circle in 2001. Photo Credit: KTM