For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at the second generation of Yamaha’s ground-breaking four-stroke racer, the 2000 YZ426F.

In 2000, Yamaha launched a bigger, badder, and just a bit better version of their revolutionary YZ-F motocross four-stroke. The rebadged YZ426F offered more performance and a harder-edged personality than the original YZ400F. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 2000, Yamaha launched a bigger, badder, and just a bit better version of their revolutionary YZ-F motocross four-stroke. The rebadged YZ426F offered more performance and a harder-edged personality than the original YZ400F. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1998, Yamaha forever changed the motocross landscape with the introduction of the first YZ400F. Once the dominant machines in motocross, big four-stroke singles had fallen out of favor in the mid-sixties with the introduction of lighter and nimbler two-strokes from Husqvarna and CZ. The new oil burners quickly pushed the booming British four-strokes to the side as riders like Torsten Hallman, Joël Robert, Bengt Åberg, and Paul Friedrichs put the new two-strokes at the front.

The updated motor on the 426F retained the same stroke as the 400F but added a 3mm larger piston, 1mm larger wrist pin, and beefed-up crank to boost torque and improve reliability. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The updated motor on the 426F retained the same stroke as the 400F but added a 3mm larger piston, 1mm larger wrist pin, and beefed-up crank to boost torque and improve reliability. Photo Credit: Yamaha

By 1970, the shift to two-strokes was complete with new competitors from Japan joining the Old-World motocross powers of Europe. Over the next twenty years, two-stroke development progressed exponentially with liquid-cooling, reed valves, variable exhaust ports, and high-tech digital ignitions turning the peaky motors of the sixties into the broad and easy-to-use powerhouses of the nineties.

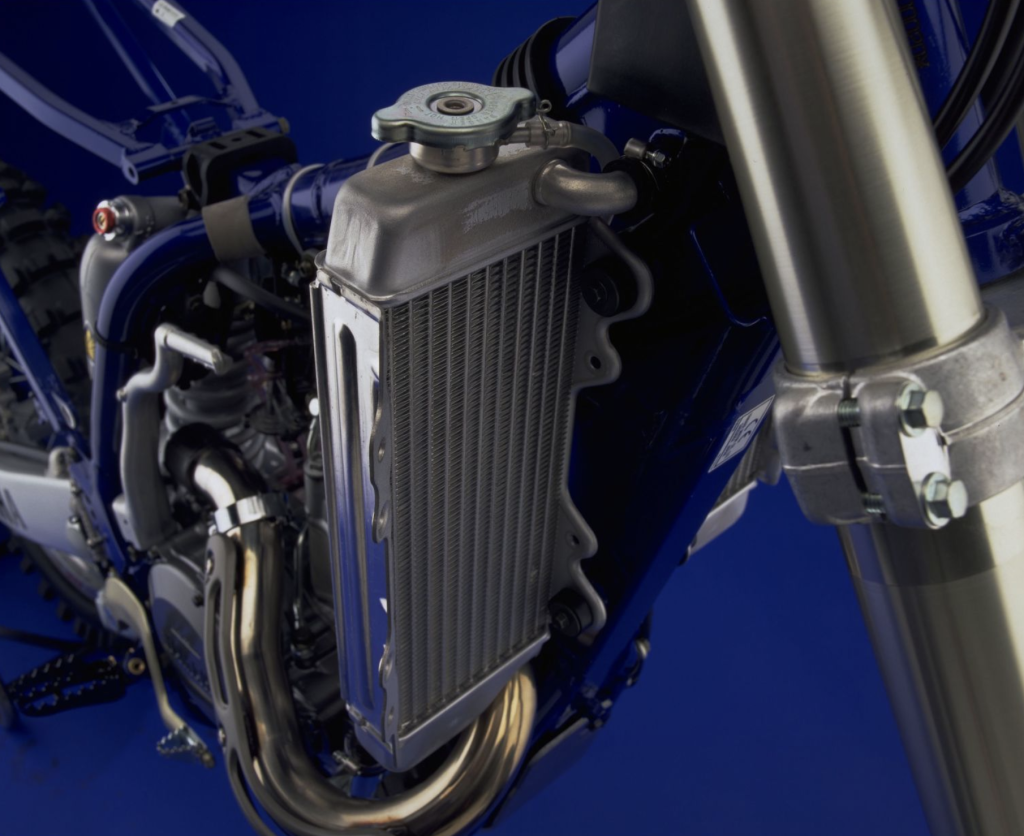

An all-new radiator for 2000 added 1mm larger tubes and an additional 10mm of width to improve cooling. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new radiator for 2000 added 1mm larger tubes and an additional 10mm of width to improve cooling. Photo Credit: Yamaha

During this explosion in two-stroke technological growth, the motocross four-stroke remained more of a sideshow than a mainstream product. Yamaha’s HL500, Husqvarna’s 510, and ATK’s super thumpers offered valve and cam aficionados an alternative to the ubiquitous smokers, but their high cost, hefty weight, and often quirky personalities held them back from being anything but playthings for well-heeled vet riders.

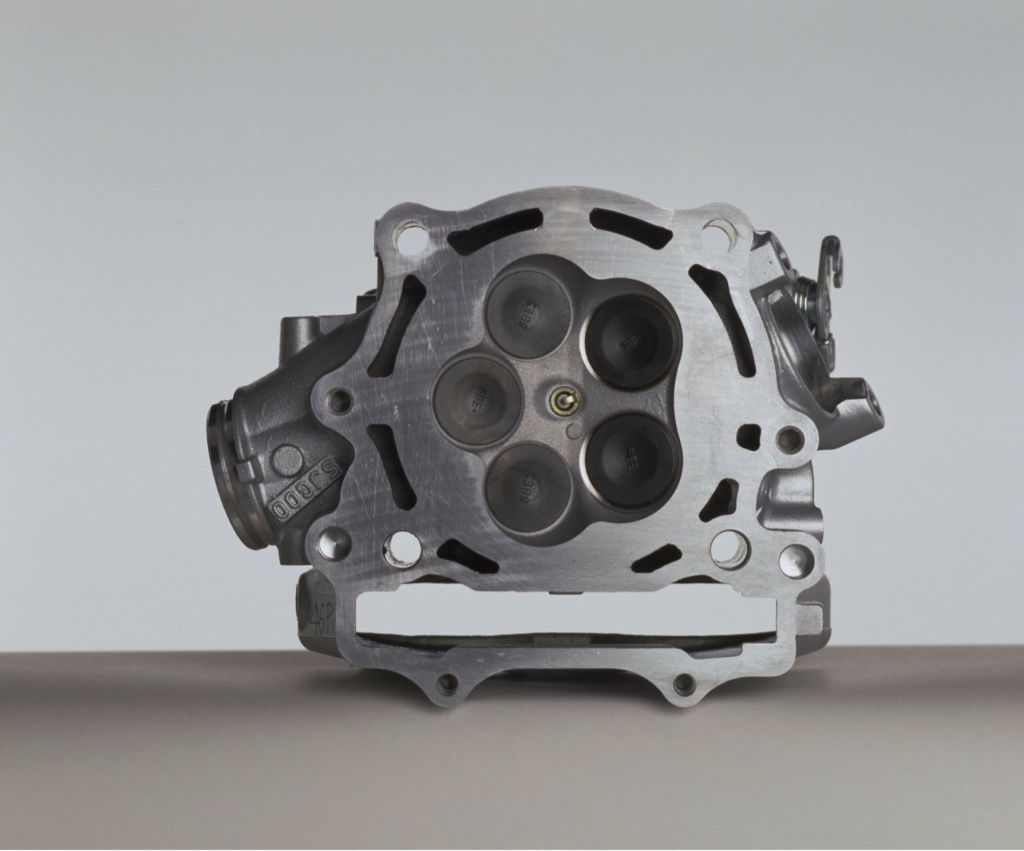

The YZ426F retained the five-valve Genesis head used on the original YZ400F. By using five smaller valves instead of four larger ones, Yamaha was able to keep the reciprocating mass of the top end as low as possible. This paid dividends in the free-revving feel of the YZ-Fs and helped provide the machines with excellent top-end longevity. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The YZ426F retained the five-valve Genesis head used on the original YZ400F. By using five smaller valves instead of four larger ones, Yamaha was able to keep the reciprocating mass of the top end as low as possible. This paid dividends in the free-revving feel of the YZ-Fs and helped provide the machines with excellent top-end longevity. Photo Credit: Yamaha

By the early nineties, Japan’s flagging interest in the Open Class left the door open for several manufacturers from Europe to bring the racing four-stroke back to prominence. Sweden’s Husaberg (led by a batch of former Husqvarna engineers), Italy’s Vertemati, and a reimagined Italian Husqvarna all led the charge to bring the four-stroke back to motocross.

An all-new frame for 2000 repositioned the steering head, shortened the wheelbase, and improved the metallurgy for improved strength. A switch from steel to aluminum for the rear subframe shaved a few precious ounces from the notoriously corpulent YZ-F. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new frame for 2000 repositioned the steering head, shortened the wheelbase, and improved the metallurgy for improved strength. A switch from steel to aluminum for the rear subframe shaved a few precious ounces from the notoriously corpulent YZ-F. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1993, Husqvarna’s Jacky Martens became the first rider to claim a World Motocross title on a four-stroke since Jeff Smith and his BSA in 1965. Two years later, Belgium’s Joël Smets raced a Swedish Husaberg to the title and he backed that up with two more 500 titles in 1997 and 1998. No longer a bit player, the Open class four-stroke was once again a power to be reckoned with in Grand Prix motocross.

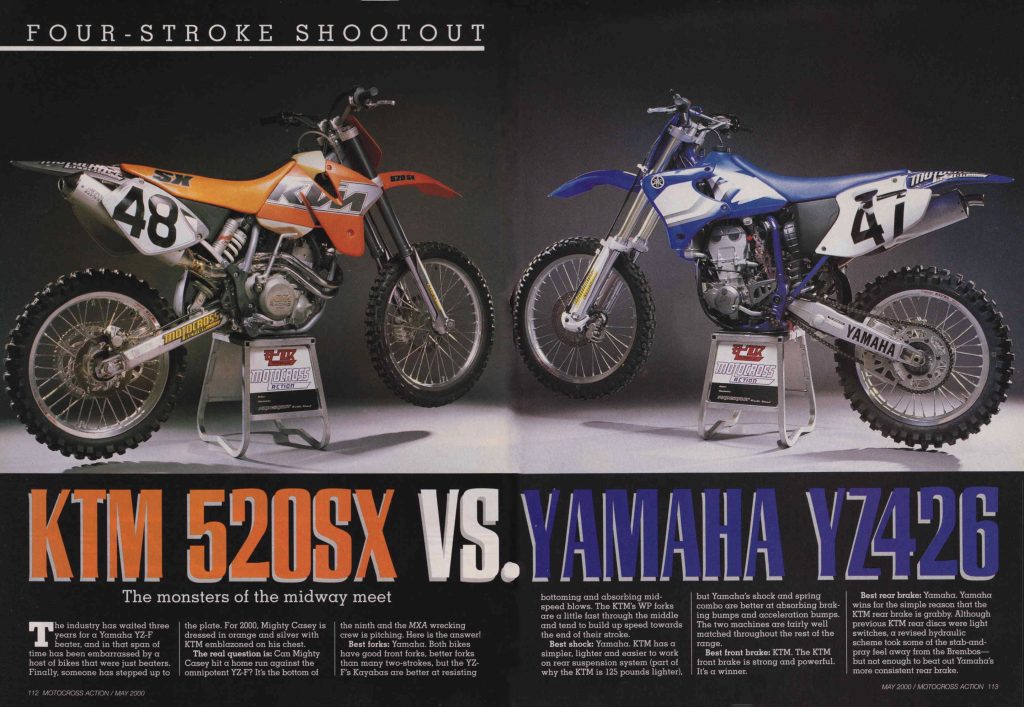

After two years of virtually unopposed Open class success, the YZ-F received its first real challengers in 2000. KTM’s all-new 520SX used the best of Austrian and Swedish knowhow to produce a very different but highly competitive alternative to the YZ426F. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

After two years of virtually unopposed Open class success, the YZ-F received its first real challengers in 2000. KTM’s all-new 520SX used the best of Austrian and Swedish knowhow to produce a very different but highly competitive alternative to the YZ426F. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the big booming four-stroke was enjoying a renaissance in Europe, it remained mostly a curiosity on this side of the pond. With the demise of the 500 National Motocross class in 1993 the big thumpers from Husqvarna, VOR (formerly Vertemati), Husaberg, and KTM were left without a real place in American racing. They were often popular in the off-road arena, but few American racers took them seriously for motocross competition.

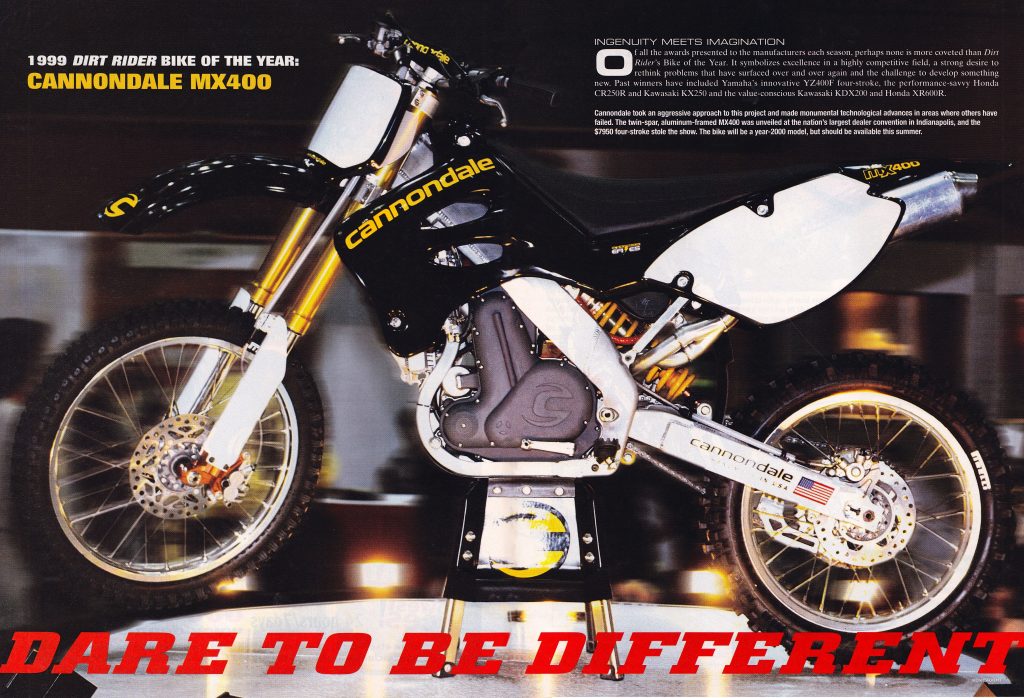

Even more hyped than the 520SX was America’s all-new four-stroke entry, the Cannondale MX400. Originally announced in 1998, the MX400 was incredibly innovative, but beset with engineering and production problems. By the time it hit the market in 2000, the Cannondale was overweight, underpowered, and woefully over budget. Today, many of its innovative ideas have made their way to the best four-strokes available, but in 2000 its push to be different was too far ahead of the curve to provide financial and market success. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Even more hyped than the 520SX was America’s all-new four-stroke entry, the Cannondale MX400. Originally announced in 1998, the MX400 was incredibly innovative, but beset with engineering and production problems. By the time it hit the market in 2000, the Cannondale was overweight, underpowered, and woefully over budget. Today, many of its innovative ideas have made their way to the best four-strokes available, but in 2000 its push to be different was too far ahead of the curve to provide financial and market success. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

In 1998, all of that changed with the introduction of Yamaha’s revolutionary YZ400F. Part YZ250 motocrosser and part YZF600R road racer, the YZ400F melded the broad power of a traditional four-stroke with the quick-revving and lithe handling of the best two-strokes. It’s 399cc short-stroke single used an ultra-light “slipper” piston and five-valve Genesis head cribbed from the YZF street bikes to provide a hybrid powerband that combined the best traits of two-and four-stroke designs. There was far less chug than the traditional four-strokes of the time and a lot more rev. The new Keihin FCR carburetor provided previously unheard-of throttle response and did away with ninety percent of the dreaded “hiccup and bog” that plagued most big four-strokes. With YZ-spec suspension, excellent handling, incredibly broad and easy-to-use power, Yamaha build quality and reliability, and a bargain basement price of $5799, the all-new YZ400F proved to be one of the most influential machines in motocross history.

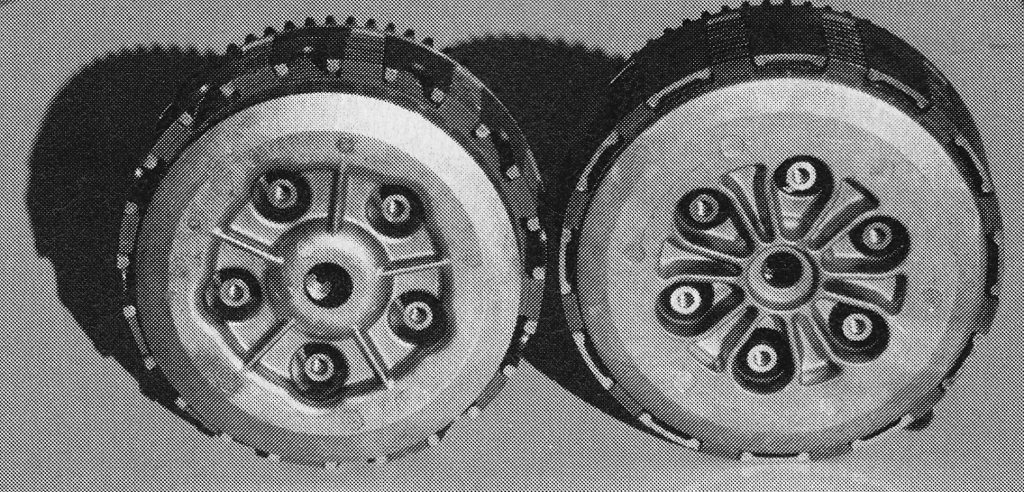

An upgraded clutch for 2000 (right) added an additional plate and a 7mm larger diameter for improved durability. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

An upgraded clutch for 2000 (right) added an additional plate and a 7mm larger diameter for improved durability. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

While the all-new YZ400F was incredibly successful in the showrooms and on the track, it was far from a perfect motocross machine. As with previous four-strokes, the YZ-F was quite portly, clocking in twenty-one pounds heavier than its YZ250 stable mate and as much as 30 pounds heavier than some of the lighter 250 two-strokes it was often dueling with. There was also a lot of compression braking to get used to and the occasional bog and flameout to contend with. If it did die in the heat of battle, getting the big single relit was no easy task due to the complex starting drill Yamaha had saddled the YZ-F with. Unlike a kick-and-go Honda XR, Suzuki DR, or any two-stroke, the YZ-F demanded you take it out of gear, find top dead center, engage a manual compression release, engage the “hot start” circuit on the carb (if the motor was hot), and give it a smooth solid kick with ABSOLUTELY no throttle. If you grabbed some throttle, forgot a step, or screwed up any of these procedures, you were left with a stubbornly unlit motor at best and a broken kickstarter at worst.

An all-new Kayaba shock for 2000 added updated valving and a new high/low compression damping adjuster. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new Kayaba shock for 2000 added updated valving and a new high/low compression damping adjuster. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Despite these quirks, however, the 1998 YZ400F proved a tremendous success. It was not immensely faster than the most powerful 250 two-strokes of the time, but its powerband was incredibly wide and extremely easy to use. It could find traction on any surface and cut under many lighter and more nimble machines due to the immense front wheel traction its hefty motor, smooth power, and tire-weighting compression braking provided. It was no RM125 in the air, but it did fly well for a 250-pound machine. If you did get out of sorts, however, it was much harder to rein it back in than a two-stroke. Sir Issac Newton aside, the first YZ400F was an incredibly competitive motocross machine and good enough to power Doug Henry to an AMA 250 National Motocross title in 1998.

The revamped Kayaba forks for 2000 added lighter internals, new valving, slicker seals, and a new low-friction treatment for the inner tubes. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The revamped Kayaba forks for 2000 added lighter internals, new valving, slicker seals, and a new low-friction treatment for the inner tubes. Photo Credit: Yamaha

After two very profitable years on the circuit and in the showrooms, it was finally time to give the YZ400F a substantial upgrade in 2000. Remarkably, the first YZ400F had proven such a shock to Yamaha’s Japanese competitors that even after two full years of production none of the other Big Four had anything close to coming out to challenge the Blue Boomer. On the Japanese side, it had the market to itself, and if you were looking to race or ride an Open bike anywhere but in the desert, the Yamaha was virtually unchallenged.

While the YZ400F caught its Japanese competitors with their pants down, things were quite a bit different in Europe. Husaberg, Husqvarna, and VOR continued to develop Open class thumpers designed for the track. They had all proven very competitive albeit with a very different feel than the road-race-inspired Yamaha. In 1995, KTM saw value in Husaberg’s four-stroke know-how and purchased the innovative but slow-selling Swedish brand. This allowed the Austrians to jump-start their stagnant four-stroke racing program which was thoroughly stuck in the eighties. At the time, their LC4 four-stroke motor was nearly a decade old and far behind the technology being implemented by their competition. By 2000, KTM finally had a new four-stroke racer ready to go and this new machine would provide the first real performance challenge to the dominance of the YZ400F.

One of the real keys to the success of the original YZ400F was its street bike-sourced Keihin FCR carburetor. The FCR pumper carb provided the YZ400F with a previously unheard-of four-stroke response and helped two-stroke converts make the transition without too many scary moments. For 2000, Keihin updated the FCR with a new straighter body, larger fuel reservoir, and simplified “hot start” circuit. Photo Credit: Yamaha

One of the real keys to the success of the original YZ400F was its street bike-sourced Keihin FCR carburetor. The FCR pumper carb provided the YZ400F with a previously unheard-of four-stroke response and helped two-stroke converts make the transition without too many scary moments. For 2000, Keihin updated the FCR with a new straighter body, larger fuel reservoir, and simplified “hot start” circuit. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Knowing that the competition in the Open class was about to get much stiffer, Yamaha set about upgrading their four-stroke superstar for 2000. Visually, the rechristened YZ426F looked nearly identical to the old 400F, but that recycled body hid a much-improved machine. The most significant of these upgrades was Yamaha’s all-new power plant which upped the YZ-F’s displacement from 399cc to 426cc. To accomplish this Yamaha maintained the same 60.1mm stroke from ’99 but upped the bore from 92mm to 95mm. In addition to growing 3mm in diameter, the new piston added a 1mm larger wrist pin for increased durability. A beefed-up crank and connecting rod featured larger bearings at both ends and a new weight balance to reduce vibration and provide a smoother power delivery. The head retained dual overhead cams and Yamaha’s unique five-valve Genesis design which allowed the valves to be smaller and lighter for excellent response and unmatched durability. A new ignition was added for 2000 with a slightly lighter flywheel to provide a freer-revving feel. As with the previous motor, the new 426F retained its dry sump configuration which carried most of its oil in a large tank inside the frame. This allowed the YZ-F to carry substantially more oil and keep that oil cooler than a wet sump design.

An all-new muffler for 2000 offered an enlarged core but no reduction in the exhaust note from the big thumper. Photo Credit: Yamaha

An all-new muffler for 2000 offered an enlarged core but no reduction in the exhaust note from the big thumper. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Matched to the new more potent top end was a revamped transmission and upgraded clutch. The new clutch featured one additional plate, an all-new hub, and a revamped basket. Each plate was increased in size by 7mm and paired with a beefed-up pressure plate. The new larger clutch required all-new side cases, but the new components could be retrofitted to the old YZ400F if you were willing to pop for the new side cases and cover as well. The transmission remained a five-speed, but the ratios were altered to match the updated power profile. The additional torque of the 426cc mill allowed Yamaha to raise the first and second gears slightly and tighten up the jump to third. The ratios for third through fifth remained unchanged.

Visually, the new 426F motor was virtually indistinguishable from the original 400F, but its performance on the track was remarkably different. The larger displacement, lighter crank, revised carburetion, and revamped transmission delivered a harder-hitting and much chunkier power delivery than the ultra-smooth original YZ400F. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Visually, the new 426F motor was virtually indistinguishable from the original 400F, but its performance on the track was remarkably different. The larger displacement, lighter crank, revised carburetion, and revamped transmission delivered a harder-hitting and much chunkier power delivery than the ultra-smooth original YZ400F. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1998, one of the keys to the success of the YZ400F had been its remarkably trouble-free carburetion. Carburetion had often been the undoing of big four-strokes with many suffering from a nasty bog if the throttle was applied too suddenly and an absolute refusal to start when hot. On the YZ400F, Yamaha substantially reduced these issues by stealing the carb straight off their YZF600R street machine. The street-bred FCR provided excellent carburetion and had no trouble keeping up with the high revs of the 400F. It still suffered from the occasional hiccup or bog, but it proved far less prone to this than most of its four-stroke competition.

For 2000, Keihin dialed up an all-new version of the FCR designed specifically for the YZ-F. Because the original FCR had come from a street machine, its body had been built at an angle to match the down-draft placement on the YZF600R. For the FCR2, Keihin recast the carb body to match its upright placement in the 426F, redesigned the hot-start circuit, and enlarged the float bowl.

Master Blaster: Riders accustomed to the electric power of the YZ400F were initially surprised by the more explosive punch of the YZ426F. The updated Yamaha thumper barked out of the hole and ripped into a blistering mid-range rush. The top-end pull was slightly more potent than the 400F, but the changes to the power profile were most notably lower down on the power curve. Fast guys loved this more potent delivery, but some more casual riders found the smoother powerband of the original 400F to be preferable to the hard hit of the 426F. Photo Credit: Corey Neuer

Master Blaster: Riders accustomed to the electric power of the YZ400F were initially surprised by the more explosive punch of the YZ426F. The updated Yamaha thumper barked out of the hole and ripped into a blistering mid-range rush. The top-end pull was slightly more potent than the 400F, but the changes to the power profile were most notably lower down on the power curve. Fast guys loved this more potent delivery, but some more casual riders found the smoother powerband of the original 400F to be preferable to the hard hit of the 426F. Photo Credit: Corey Neuer

With the larger displacement and higher power, the Yamaha engineers felt the YZ-F could use improved cooling so for 2000 they enlarged the radiators, dropped the black paint, upsized the hoses, and redesigned the louvers to direct more air to the cores. The exhaust was all-new as well with an enlarged head pipe and larger core for the muffler.

Frame changes for 2000 included updated geometry that repositioned the steering head rearward 5mm and reduced the wheelbase 5mm for improved turning. All-new metallurgy for the chromoly frame increased strength and reduced weight for 2000 with a switch from steel to aluminum for the subframe further trimming ounces. New clamps added additional bracing for the lower clamp and repositioned the bar mounts 10mm forward for improved ergonomics. A redesigned clutch perch for 2000 featured a revised ratio and a new on-the-fly adjuster. The clutch cable was also upgraded to a new stainless-steel design that Yamaha claimed would provide smoother operation.

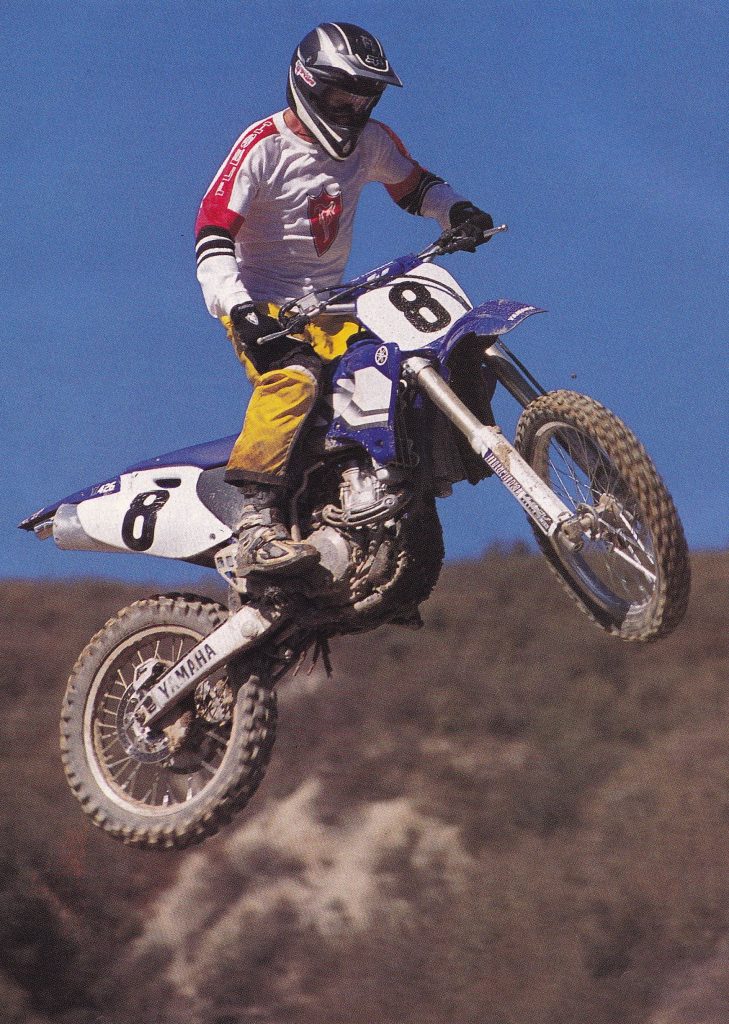

The YZ426F dropped two pounds for 2000, but it remained the plus-sized model of the Open Class. KTM’s new 520SX undercut it by fifteen pounds and every two-stroke it was likely to face bested it by at least twenty. While this weight disadvantage was not always an issue, it was impossible to ignore if the YZ426F stepped out of line or got a bit too sideways in the air. While antics like this were possible, the YZ426F was not the hot setup for the X-Games crowd in 2000. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

The YZ426F dropped two pounds for 2000, but it remained the plus-sized model of the Open Class. KTM’s new 520SX undercut it by fifteen pounds and every two-stroke it was likely to face bested it by at least twenty. While this weight disadvantage was not always an issue, it was impossible to ignore if the YZ426F stepped out of line or got a bit too sideways in the air. While antics like this were possible, the YZ426F was not the hot setup for the X-Games crowd in 2000. Photo Credit: Ken Faught

Most of the bodywork on the new YZ426F was a carryover from the year before, but there were a few updates of note. Cosmetically, the most obvious change was the new front fender which featured a sleeker profile and less angular shape. This was the first update to the YZ’s fender design since the debut of the “arrow” look in 1992. The front number plate was also revamped slightly with a new mounting point designed to work with the updated clamps. The radiator shrouds looked the same as the year before but ribs on the inside provided additional strength and prevented bowing at the rear mount. All-new graphics for 2000 increased the size of the Yamaha “strobe” on the tank and shrouds and mimicked the look of Jimmy Button’s factory YZ400F from 1999. Unlike the two-stroke YZs, which adopted a somewhat controversial white airbox for 2000, the 426F’s airbox remained the traditional grey of the previous model. In the minds of many at the time, this was to the 426F’s benefit.

The updated KYB “bumper” forks for 2000 did an excellent job of taming the track and were much better controlled on hard hits than the year before. Bottoming remained an issue for fast guys, but the overall action was in the ballpark for most riders below the pro class. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The updated KYB “bumper” forks for 2000 did an excellent job of taming the track and were much better controlled on hard hits than the year before. Bottoming remained an issue for fast guys, but the overall action was in the ballpark for most riders below the pro class. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the suspension front, the new 426F featured upgrades both front and rear. Up front, the YZ-F retained the same inverted Kayaba “bumper” fork as in 1999, but Yamaha made several refinements to the design to improve performance. Internally, Kayaba moved from steel to aluminum for the cartridge piston, added a new slicker coating to the upper stanchion tubes, installed special “low friction” fork seals, and updated the valving to provide better bottoming resistance. Spring rates remained unchanged with the stock coils coming in at 0.46kg/mm. Overall travel was set at 11.8” with external adjustments available for compression and rebound damping.

In the rear, Yamaha added an all-new Kayaba shock with increased adjustability and all-new valving. The new damper added a high/low-speed compression adjuster to go with the external rebound selector. All-new valving was added but the spring rate remained unchanged at 5.2kg/mm. Overall travel remained the same as in 1999 with 12.4” available.

While the rivalry with Cannondale never really materialized, the challenge from KTM proved quite legitimate. The new 520SX was slimmer, lighter, faster, and better finished than the Yamaha, but its chassis and suspension were less refined than the blue bullet. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While the rivalry with Cannondale never really materialized, the challenge from KTM proved quite legitimate. The new 520SX was slimmer, lighter, faster, and better finished than the Yamaha, but its chassis and suspension were less refined than the blue bullet. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

On the track, the YZ426F looked very similar to the year before but its performance was radically different. The increase in displacement and other motor updates transformed the YZ-F from a smooth and easy-to-ride revver into a fire-breathing beast of an Open class machine. When experienced two-stroke riders first rode the all-new YZ400F, they marveled at its untraditional “four-stroke” feel. At the time, most big four-stroke singles chugged, rumbled, and torqued around the track. They came on early with a huge mountain of torque, turned relatively few revs, and preferred to be short-shifted rather than pinned to the stops. With the new YZ400F, most of that chug was traded for an electric style of power that spun up fast, hooked up well, and revved to the moon. There was very little “hit” in the 400F’s powerband and that made it super flexible and easy to ride.

With the 426F, Yamaha chose to bring back a bit of that traditional big four-stroke bark to the YZ-F’s powerband. Where the old motor’s powerband was smooth and linear, this new version was bulging at the seams and ready to pounce. It barked off idle, blasted through the midrange, and shrieked on top. There was much more hit down low and a stronger pull in the middle. On top, it pumped out two more horses than the old 400F but most of its advantage was below the rev-limited stratosphere. Where the 400F purred, the 426F growled and its powerband was much more akin to a big BSA of the past than a high-powered Honda Civic.

The updated shock on the Yamaha delivered a more refined ride than the KTM and offered the best combination of comfort and control in the class. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The updated shock on the Yamaha delivered a more refined ride than the KTM and offered the best combination of comfort and control in the class. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While this change made many throttle jockeys happy, it did surprise and intimidate a few riders who traded in their mellow 400F for the Top Fuel 426F. The new powerband was much more abrupt and the bike felt more like a traditional Open class machine than the “tweener” 400F. It was still far more civil than a CR500R or KX500 two-stroke, but it demanded respect when the throttle was whacked open. Compared to the all-new KTM 520SX, the Yamaha hit harder, revved faster, and revved farther. It felt far more explosive, but many riders preferred the power of the larger and mellower KTM. Ironically, its new Husaberg-based motor provided a powerband closer to the old YZ400F, and to many this was preferable to the revamped Yamaha’s blast. Both were incredibly competitive but if you were looking for a more powerful YZ400F you might have been happier going orange in 2000.

Another significant key to the success of the original YZ400F/426F was its remarkable durability. Most racers at the time had significant and well-founded concerns about the long-term reliability of a motocross four-stroke and if the Yamahas had launched with the same issues the first-gen KX250F suffered from a few years later it might have spelled the end of the four-stroke Renaissance. Thankfully for Yamaha, however, the proven Genesis head design, adequate cooling, and generous oil capacity the Yamahas enjoyed allowed the YZ-Fs to avoid the four-stroke pitfalls that had plagued so many of its rivals. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Another significant key to the success of the original YZ400F/426F was its remarkable durability. Most racers at the time had significant and well-founded concerns about the long-term reliability of a motocross four-stroke and if the Yamahas had launched with the same issues the first-gen KX250F suffered from a few years later it might have spelled the end of the four-stroke Renaissance. Thankfully for Yamaha, however, the proven Genesis head design, adequate cooling, and generous oil capacity the Yamahas enjoyed allowed the YZ-Fs to avoid the four-stroke pitfalls that had plagued so many of its rivals. Photo Credit: Yamaha

If you could handle the increased hit, the 2000 YZ426F motor was an absolute gem. Its revamped ratios were a perfect match for the beefier power and every shift was silky smooth. The upgraded clutch proved more durable if pushed and the feel at the lever was excellent. Hammering the plates like it was a 125 was not advisable but as long as you remembered you were riding an Open classer it was a good clutch. Previous YZ400Fs had been pretty hot runners, and the new larger radiators did a good job of keeping the big single from boiling over. It was still not a great idea to let it idle too long on the line, but it was generally good at keeping its coolant where it belonged. If it did get hot, however, it remained a bit of a stubborn starter. The tedious starting drill remained, and the redesigned hot start circuit left many wondering if the FCR2 carb was an improvement. There was still a bit of the occasional hiccup and bog and the 426F often felt more stubborn to light than the old 400F. Once you got the drill down, it was a reliable starter, but everyone preferred the kick-and-go simplicity of the KTM to the arcane mysteries of the Yamaha.

On the suspension front, the YZ426F was much improved for 2000. The revamped KYB forks did a much better job of holding up and not blowing through their stroke on hard hits. They were well-damped and plush in action. Fast guys and high flyers still needed stiffer springs, but the YZ-F no longer felt like someone had stuck 125 forks on your 250-pound Open bike.

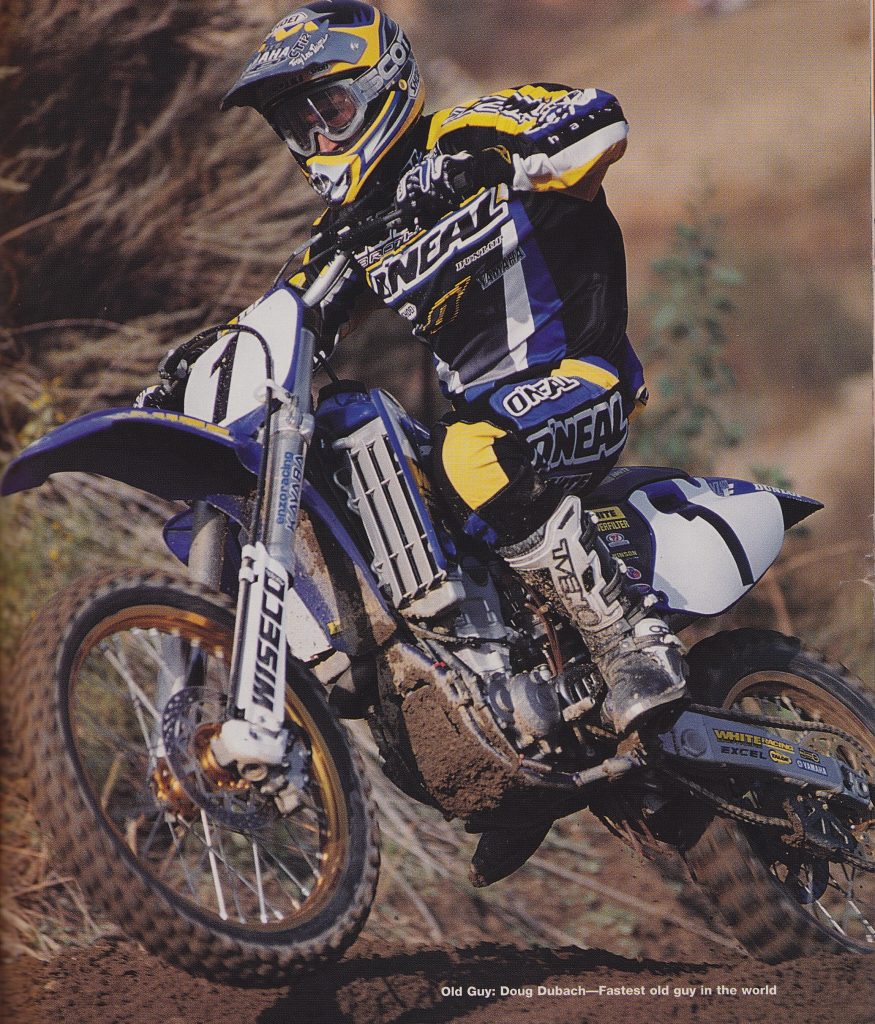

Long-time Yamaha stalwart Doug Dubach was the face of the all-new YZ-F, and he continued his PR tour by racing the redesigned YZ426F to another World Vet title in 2000. Photo Credit: Motocross Journal

Long-time Yamaha stalwart Doug Dubach was the face of the all-new YZ-F, and he continued his PR tour by racing the redesigned YZ426F to another World Vet title in 2000. Photo Credit: Motocross Journal

In the rear, the YZ426F was once again an excellent performer. The new multi-adjuster KYB shock offered tons of customizability and most racers were able to find a comfortable setting by playing with the available external adjustments. Spring rate and damping performance were in the ballpark for the 426F’s target demo and nearly everyone raved about its plush and well-controlled performance. Overall, it was the most well-rounded suspension package available in the Open class in 2000.

On the handling front, the YZ426F turned out to be another home run for Yamaha. The shorter wheelbase and changes in weight bias yielded an even sharper turner for 2000. The new bike was an absolute shredder and by far the most accurate turner in the Open class. Despite its girthy proportions, the big Yamaha had little trouble turning under, over, and around many of its 250 rivals. The front end stuck like the tire was made of fly paper and you could take lines that were nearly impossible to execute on a 250 smoker. Slick off-cambers that were a nightmare on other machines were a piece of cake on the mighty 426F. At speed, the 426F remained rock solid as well and it was nearly impossible to knock it off its line once it built up a head of steam.

While the YZ426F was far from a feather, it was a very capable jumper. Its strong power, excellent chassis, and well-sorted suspension made most leaps a point-and-shoot affair in 2000. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the YZ426F was far from a feather, it was a very capable jumper. Its strong power, excellent chassis, and well-sorted suspension made most leaps a point-and-shoot affair in 2000. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Of course, the flip side to this was the fact that it was equally difficult to pull it back in line if something did upset its apple cart. The big weight and strong gyro effect of the motor made the 426F difficult to throw around and there was no denying the extra 20-30 pounds it was lugging around if things got a bit buck wild. The motor’s strong compression braking was also a bit tricky if you were accustomed to a free-wheeling two-stroke. Snapping the throttle shut on the face of a jump was a recipe for disaster and most riders quickly learned it was best to use a bit of trailing throttle to keep the big four-two-six pointed in the right direction. With its excellent suspension and big power, there wasn’t any gap the Why-Zed could not conquer. Excellent low-end power and superior traction made quick work of doubles out of turns that were tricky to execute on two-stroke. As long as you were smooth on the throttle, big air was easy peasy on the 426F. Sick whips and mega turndowns were not on the menu, but the bike was a remarkably good flier for such a big and heavy machine.

The YZ426F’s bars remained disappointingly buttery, but an all-new on-the-fly clutch adjuster improved the Yamaha’s feature set for 2000. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The YZ426F’s bars remained disappointingly buttery, but an all-new on-the-fly clutch adjuster improved the Yamaha’s feature set for 2000. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the detailing front, the YZ426F was a very well-thought-out machine. The stock steel bars were made of recycled butter and the decals were flimsy, but most of the components were well-built and nicely finished. The grips, seat, and ergonomics were comfortable and the 426F was generally an excellent place to do business. The brakes worked great, the transmission was silky smooth, and the motor was virtually without vibration.

Despite its girthy proportions, the YZ426F was a surprisingly adept handler. Turning was super sharp and the big thumper could hook up on nearly any surface. Deep sand and mud were not its perfect environment but the 426F was easily the best do-it-all handler in the Open class. Photo Credit Motocross Action

Despite its girthy proportions, the YZ426F was a surprisingly adept handler. Turning was super sharp and the big thumper could hook up on nearly any surface. Deep sand and mud were not its perfect environment but the 426F was easily the best do-it-all handler in the Open class. Photo Credit Motocross Action

Unlike many high-strung four-strokes, the YZ400F and its 426F successor proved remarkably reliable. The Yamaha four-strokes did not drink oil excessively, chew through valves, or constantly overheat. Their large external oil tanks kept things cool and allowed for a margin of error if the big thumpers burned some black gold in the heat of battle. Reliability was always a concern in racing four-strokes, but Yamaha’s super thumpers went a long way toward allaying those concerns. The 426F’s valvetrain and top end were virtually bulletproof, and it was not uncommon to race the YZ-F a full season before needing to dig into the top end. As long as you changed the oil and filters regularly and kept an eye on the dipstick, the big 426F was as reliable as any high-performance racing machine could hope to be.

Living with the 426F was generally a trouble-free affair, but there were still a few concerns native to its two extra strokes. Carburetion was generally well sorted on the 426F, but the FCR2 remained guilty of the occasional hiccup or flameout. Supercross-style obstacles were particularly concerning and best approached with care as the bike remained prone to the odd bog if the throttle was whacked open too suddenly. It was far less of an issue than on many old-school thumpers, but this classic four-stroke bugaboo was always there waiting to rear its ugly head at an inopportune moment. Aftermarket accelerator pumps with larger fuel reservoirs helped lessen this problem, but it remained a concern if you were planning to take your 426F anywhere near a Supercross track.

Jimmy Button was Yamaha’s Top Gun on the YZ426F in 2000. Unfortunately for Button, however, a practice crash in round three in San Diego would leave the Yamaha star temporarily paralyzed and out for the season. Button would eventually regain much of his movement, but the freak accident would signal the end of the popular veteran’s career. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Jimmy Button was Yamaha’s Top Gun on the YZ426F in 2000. Unfortunately for Button, however, a practice crash in round three in San Diego would leave the Yamaha star temporarily paralyzed and out for the season. Button would eventually regain much of his movement, but the freak accident would signal the end of the popular veteran’s career. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For many two-stroke converts, starting the 426F remained its biggest barrier to acceptance. Most riders could memorize the Yamaha’s elaborate starting drill but getting it right in the heat of the battle was not always easy. If you took your time, followed all the steps, and remembered to stay away from the throttle, then the 426F was a reliable starter, but if you panicked, skipped a step, left it in gear, or accidentally goosed the throttle, then you might be in for a lot of cursing as your competition rode by. Practicing the drill helped, but the dreaded mid-moto stall was always lurking in the wings, waiting to ruin your moto.

In 1998, Yamaha rewrote the four-stroke racing rulebook with their original YZ400F and in 2000, they added a second chapter with their revamped YZ426F. The new 426F was slightly harder-edged but still offered all the advantages that had made the original Yamaha thumpers such a runaway hit. Big, burly, and a bit of a pain to start, the YZ426F offered Open-class aficionados an excellent platform from which to chase motocross glory. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1998, Yamaha rewrote the four-stroke racing rulebook with their original YZ400F and in 2000, they added a second chapter with their revamped YZ426F. The new 426F was slightly harder-edged but still offered all the advantages that had made the original Yamaha thumpers such a runaway hit. Big, burly, and a bit of a pain to start, the YZ426F offered Open-class aficionados an excellent platform from which to chase motocross glory. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Overall, the 2000 Yamaha YZ426F turned out to be another home run for Yamaha. It was faster, better suspended, and sharper handling than before, but the competition was quickly catching up. Cannondale’s new MX400 turned out to be mostly vaporware, but the all-new 520SX from KTM proved to be a real contender. It undercut the Yamaha by fifteen pounds, was far easier to start, and just a bit faster. Its suspension was not as supple as the YZ-F, and its four-speed transmission limited its non-motocross appeal, but in the minds of many it was at least the Yamaha’s equal. No longer a quirky niche, the battle for four-stroke motocross supremacy had officially begun.