For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new CR250R for 1985.

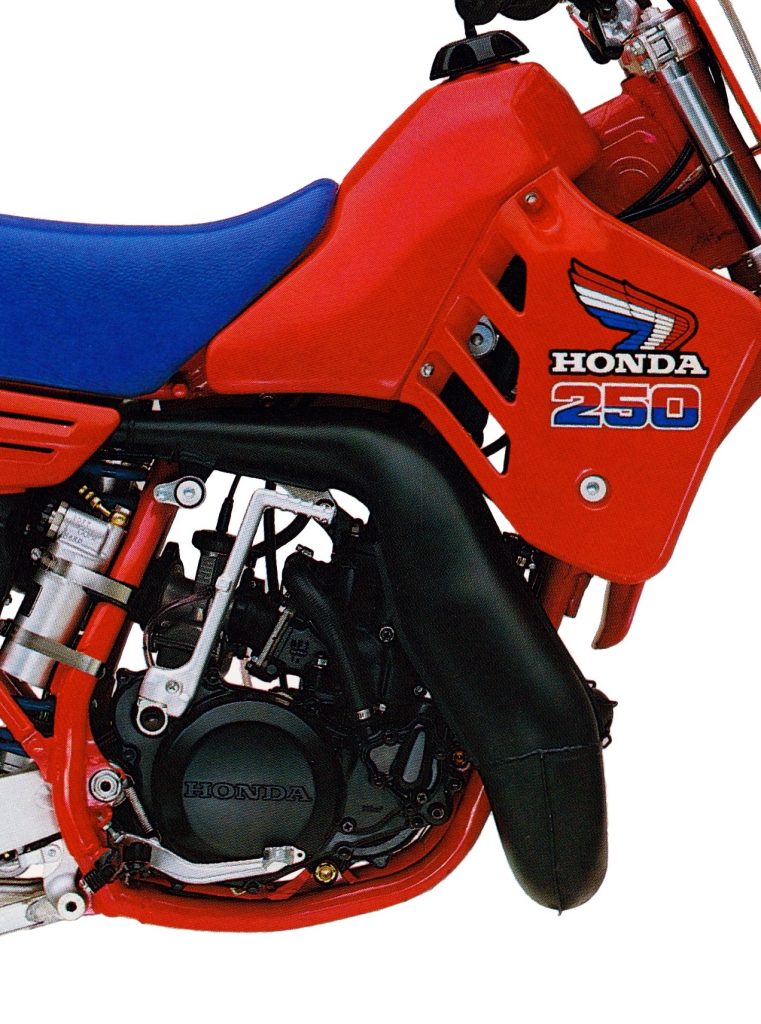

The all-new Honda CR250R was a real looker in 1985 and remains one of the most attractive machines of its era. Photo Credit: Honda

The all-new Honda CR250R was a real looker in 1985 and remains one of the most attractive machines of its era. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1984, Honda’s deuce-and-a-half featured the fastest motor in the 250 division. The fire-breathing 246cc mill rocketed out of turns with an explosive midrange blast that just kept on pulling until the CR was at the front. It was head and shoulders faster than the other machines in the class and a huge advantage on the track. With its impressive horsepower advantage, the CR was the unanimous pick for the best 250 in the MX magazine shootouts despite its mediocre suspension and suspect reliability.

Tick Tick BOOM: Honda’s CR250R was the rompin’ stompin’ master blaster of the 250 class in 1984. Its motor was considerably faster than any other machine in the class, but its numerous reliability issues made ownership a bittersweet experience. Photo Credit: Honda

Tick Tick BOOM: Honda’s CR250R was the rompin’ stompin’ master blaster of the 250 class in 1984. Its motor was considerably faster than any other machine in the class, but its numerous reliability issues made ownership a bittersweet experience. Photo Credit: Honda

Today, Honda’s brand is synonymous with reliability, but its motocross machines were not always the paragons of dependability they are today. In the early eighties, all the brands faced reliability and developmental issues as engineers pushed the boundaries of design and performance. Long-travel suspension, liquid-cooling, and variable exhaust ports all boosted performance while also introducing new engineering challenges to be overcome.

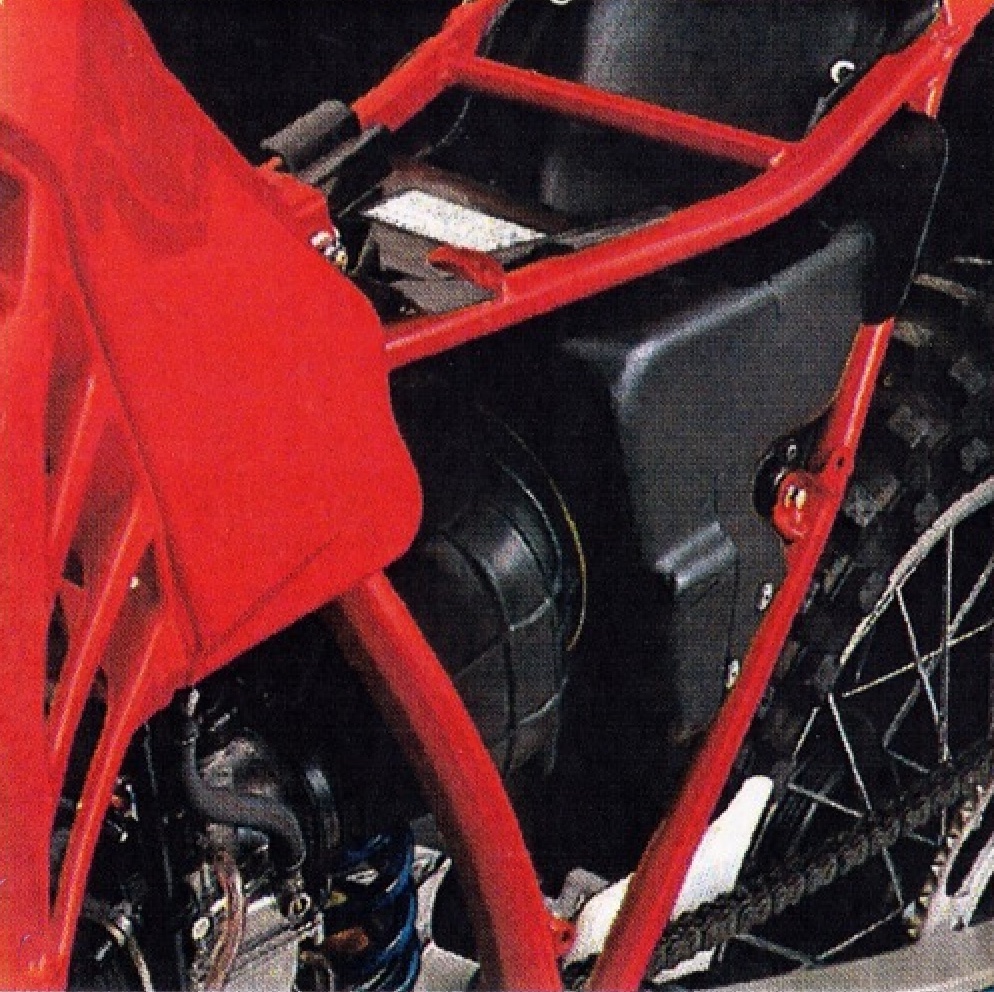

An all-new frame for 1985 was stronger with a new square downtube, beefed-up cross-members, and strategically placed reinforcements. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new frame for 1985 was stronger with a new square downtube, beefed-up cross-members, and strategically placed reinforcements. Photo Credit: Honda

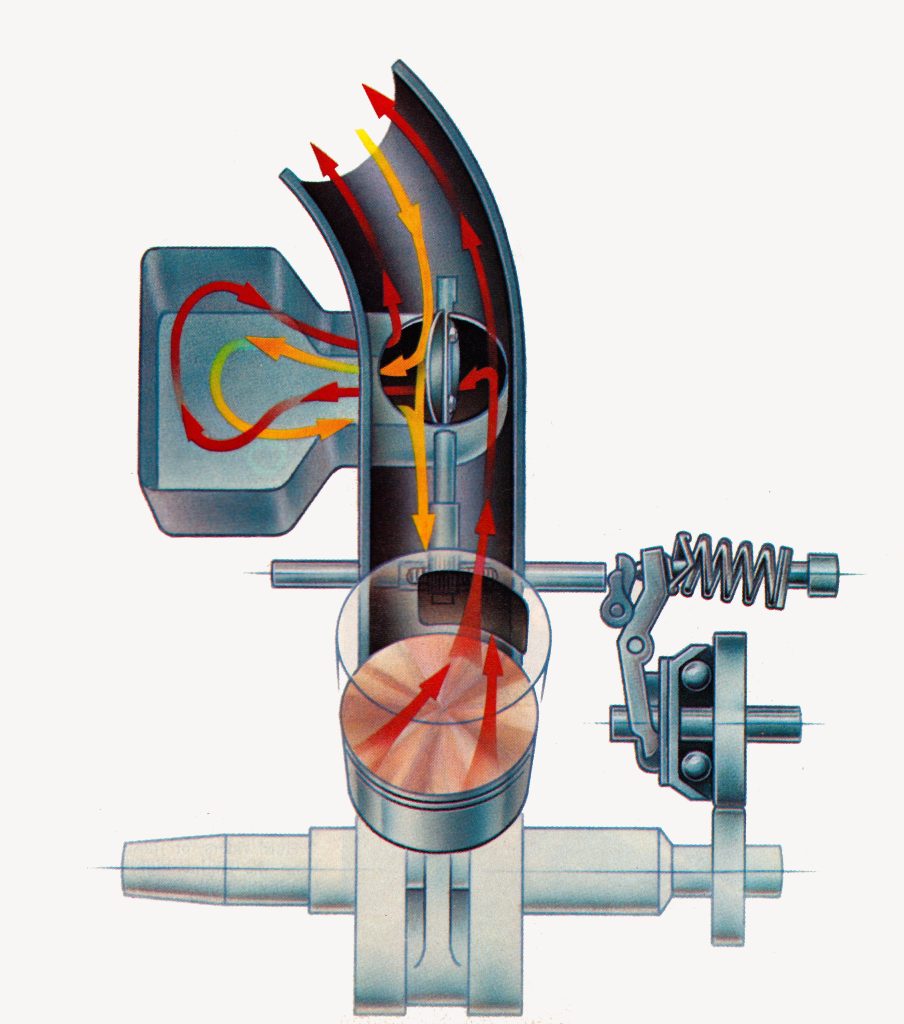

In 1984, Honda’s motor team nailed the performance end of the equation but fell short on the durability side of the scale. The new motor introduced Honda’s first “power valve” in the form of an exhaust sub-chamber built into the side of the cylinder, designed to boost low-end torque by increasing head pipe volume at low RPM. Dubbed the Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber (ATAC), Honda’s system did not alter exhaust port timing, but rather focused on finetuning power by allowing the stock expansion chamber to act as two pipes in one. Aside from the ATAC system, Honda’s 1984 CR250R motor was quite conventional for the time with liquid-cooling, a solid-state CDI electronic ignition, a six-pedal cylinder-reed intake, and a 36mm round-slide Keihin carburetor.

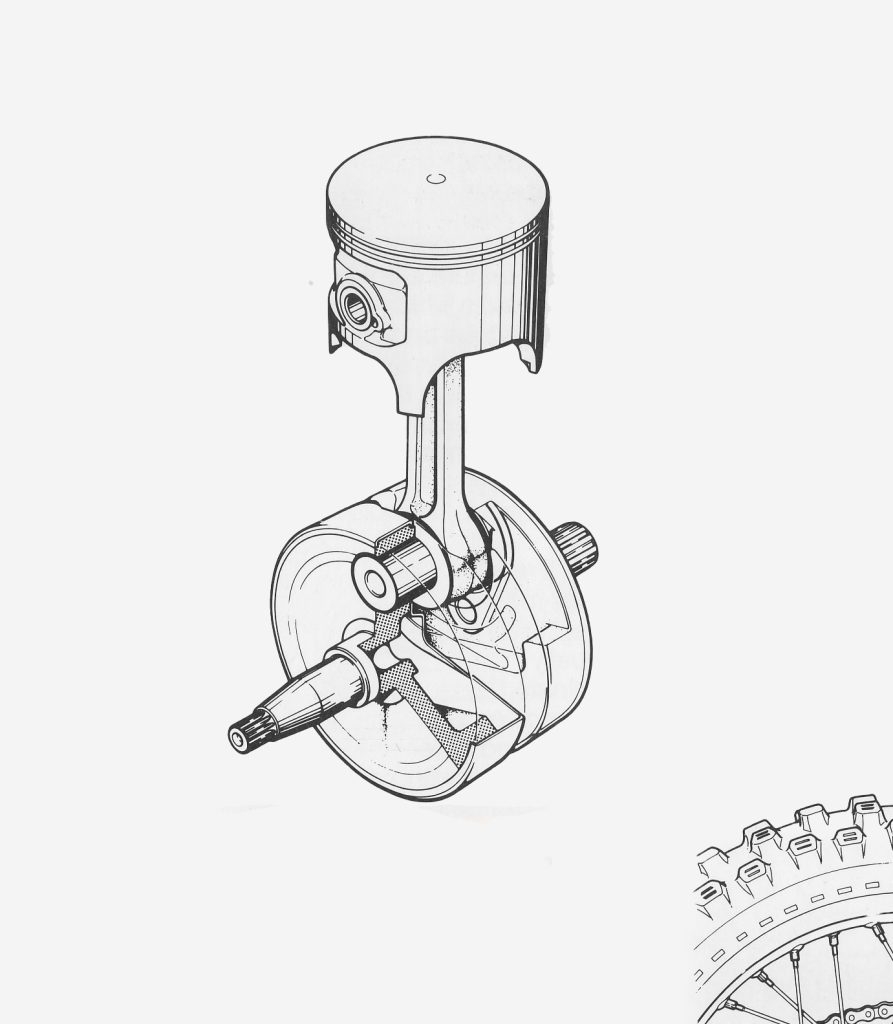

In 1984 the CR’s crankshaft had been a common point of failure, so in 1985 Honda removed the failure-prone plastic bearing separators and replaced them with more durable steel components. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1984 the CR’s crankshaft had been a common point of failure, so in 1985 Honda removed the failure-prone plastic bearing separators and replaced them with more durable steel components. Photo Credit: Honda

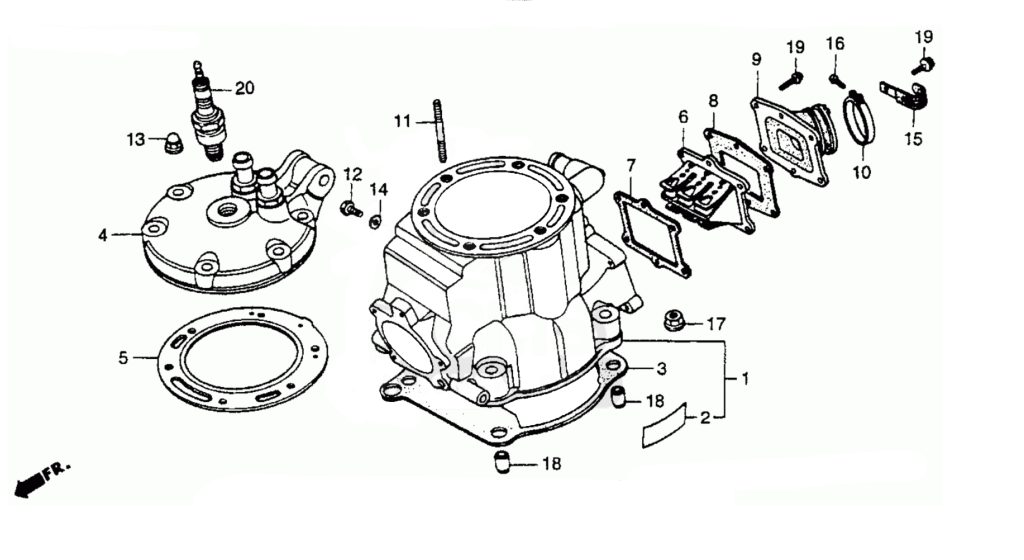

In 1984, Honda enlarged the main exhaust port and removed its support bridge to improve exhaust flow. This paid dividends on the dyno but caused the CR to catch rings and crack pistons. For 1985, an all-new cylinder offered redesigned porting and a return of the exhaust bridge. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1984, Honda enlarged the main exhaust port and removed its support bridge to improve exhaust flow. This paid dividends on the dyno but caused the CR to catch rings and crack pistons. For 1985, an all-new cylinder offered redesigned porting and a return of the exhaust bridge. Photo Credit: Honda

When designing the 1984 motor update, one fateful decision Honda’s engineers made was to enlarge the main exhaust port and eliminate the ’83 model’s support bridge. This was done to improve exhaust flow and increase top-end power. They also hollowed out the crank and lightened it considerably to increase the motor’s response. On the dyno, these changes proved to be a tremendous success, but riders quickly found that the increased power came with a commensurate drop in reliability. The large non-bridged exhaust port caused rings to snag and pistons to crack, and the new lighter crank liked to spin its main bearings. Hard-ridden CRs also suffered transmission issues that further soured riders on the red-ripper’s charms. While it was running it was amazing, but keeping it in one piece was often a challenge.

In 1984, Honda introduced its first version of a “power valve” in the form of the Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber or ATAC. The ATAC consisted of a centrifugal ball-ramp governor, exhaust valve, and small resonance chamber. By opening and closing this exhaust valve, Honda’s engineers were able to alter the volume of the exhaust header to optimize power and provide a boost of torque at low RPM. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1984, Honda introduced its first version of a “power valve” in the form of the Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber or ATAC. The ATAC consisted of a centrifugal ball-ramp governor, exhaust valve, and small resonance chamber. By opening and closing this exhaust valve, Honda’s engineers were able to alter the volume of the exhaust header to optimize power and provide a boost of torque at low RPM. Photo Credit: Honda

The 1984 motor’s many reliability issues were well documented, and Honda went into the 1985 redesign with the aims of improving its power delivery and exorcizing its many mechanical gremlins. The 1984 motor had an all-new design, adding the ATAC system and reversing the position of the output shaft and kickstarter. This change allowed Honda to reduce the size of the rear hub and please riders uncomfortable with the CR’s European-inspired left-side kicker. For 1985, Honda retained the right-side kicker and left-side output but redesigned virtually everything else.

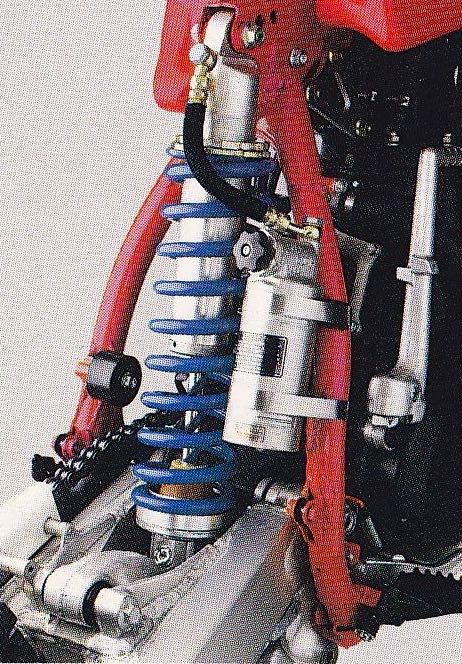

An all-new Showa damper offered more travel, increased oil capacity, and a larger shock body and piston for 1985. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new Showa damper offered more travel, increased oil capacity, and a larger shock body and piston for 1985. Photo Credit: Honda

First up was an all-new cylinder that repositioned the ATAC’s exhaust resonance chamber from inside the cylinder to an external position below the exhaust manifold. In 1984, the 250’s system was much more complicated to service than the ATAC used on the CR125R, so in 1985 Honda moved the CR250R to the 125’s design. The basic function of the ATAC was unchanged, but the new design moved the most maintenance-intensive parts of the exhaust valve mechanism and resonance chamber to the exhaust manifold, where they could be easily removed for servicing.

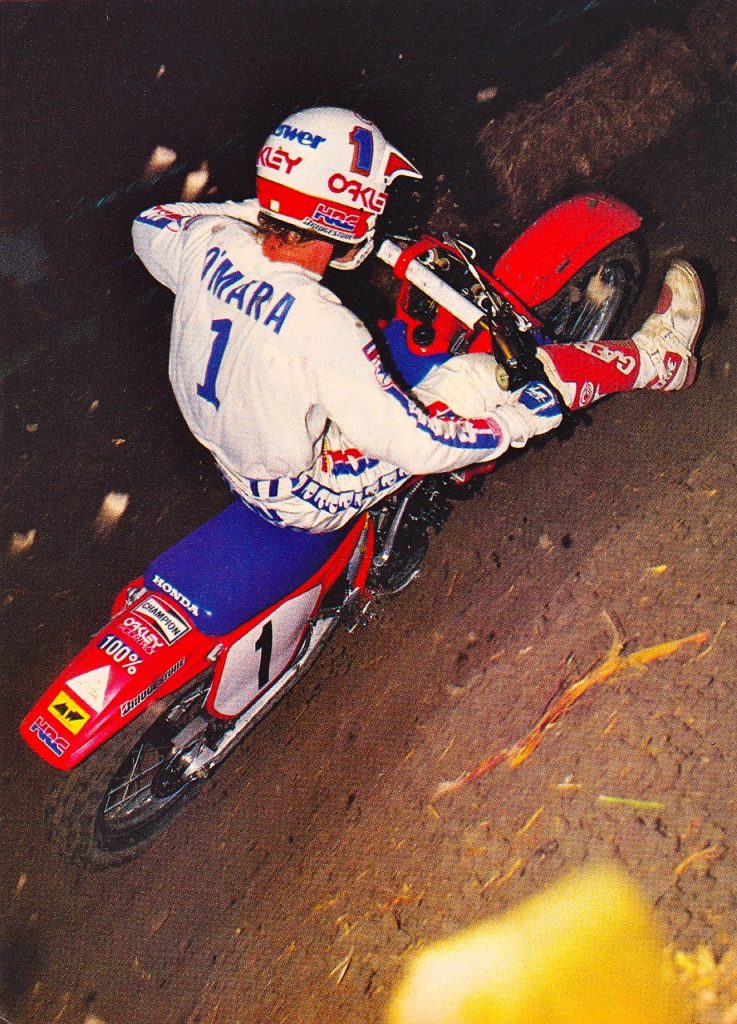

The Works: The 1985 season turned out to be the pinnacle of the works bike era in America. One-off factory machines like Johnny O’Mara’s RC250 shared not a single part with the production CR250R you could buy at your local Honda dealer. The introduction of the production rule for the 1986 season meant bikes like this were no longer legal for US racing. Photo Credit: David Dewhurst

The Works: The 1985 season turned out to be the pinnacle of the works bike era in America. One-off factory machines like Johnny O’Mara’s RC250 shared not a single part with the production CR250R you could buy at your local Honda dealer. The introduction of the production rule for the 1986 season meant bikes like this were no longer legal for US racing. Photo Credit: David Dewhurst

In addition to the redesigned ATAC, the 1985 cylinder featured all-new porting and a return of the exhaust bridge that had been sorely missed in the 1984 design. The bore and stroke remained unchanged at 66mm x 72mm with the same 8.6:1 compression ratio and 246cc of displacement as in 1984. A new crank for 1985 added revised main bearings with steel retainers in place of the problematic plastic retainers used in 1984. New cases for 1985 also offered reinforcements at the cylinder-case junction to reduce the chance of any leaks.

Upgraded wheels for 1985 featured larger spokes and beefed-up nipples to prevent the wheel failures that were common in 1984. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Upgraded wheels for 1985 featured larger spokes and beefed-up nipples to prevent the wheel failures that were common in 1984. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

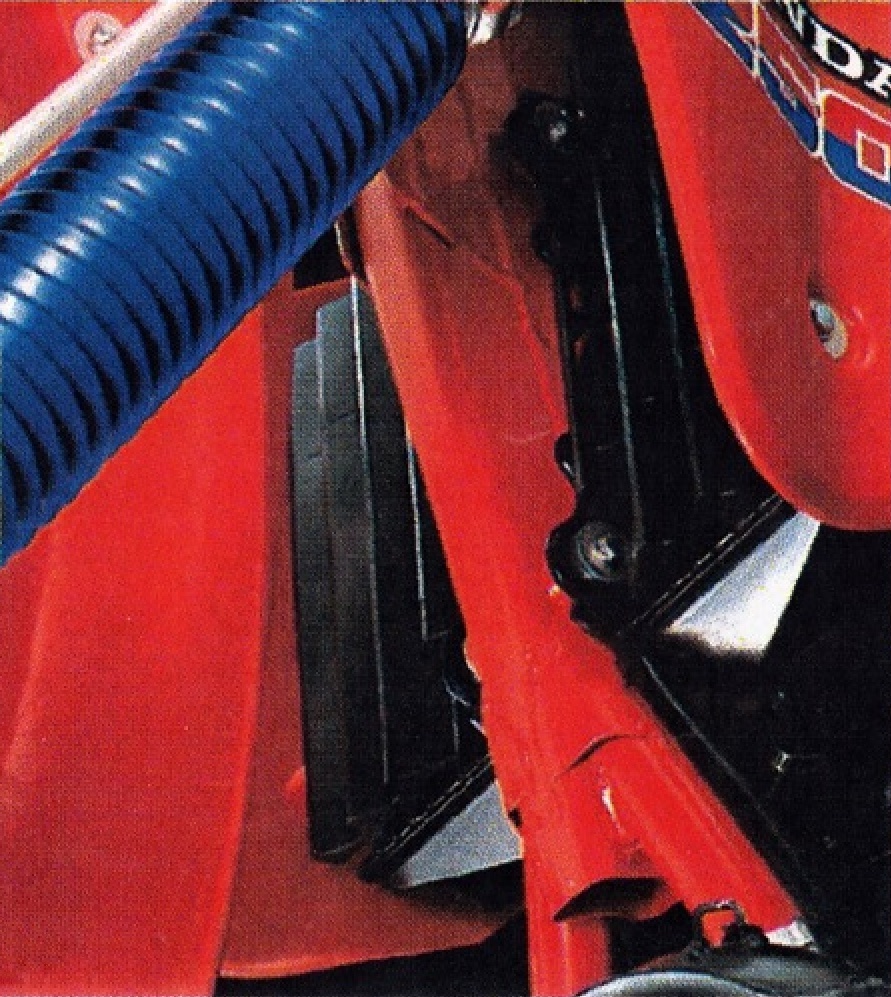

In a nod to further improving reliability, the coolant passages inside the cylinder and head were enlarged and reshaped to improve flow, and both radiators were increased in length by 0.7 inches. All-new angled louvers improved airflow to the radiators and protected them from roost, while an increase in the wall thickness of the radiators’ outer shell reduced the chances of damage or deformation in a crash. A third mount was also added to each radiator for improved durability and crash resistance. An all-new coolant line was injection molded into one piece instead of using three separate lines for increased durability and less chance of leaks. The seal for the water pump was also upgraded with Teflon for improved sealing and reliability.

All-new bodywork for 1985 (right) featured a slimmer tank to make getting forward in turns easier than on the 1984 (left) machine. Photo Credit Motocross Action

All-new bodywork for 1985 (right) featured a slimmer tank to make getting forward in turns easier than on the 1984 (left) machine. Photo Credit Motocross Action

The new motor continued to draw fuel from a six-pedal reed valve mounted to the rear of the cylinder. Feeding fuel and air to the intake was an all-new 36mm Keihin flat-slide PJ carburetor that was lighter than the old round-slide mixer that it replaced. The new carb offered an easy-to-adjust external idle circuit built into the choke and offered improved fuel metering and atomization for increased throttle response over the previous design. A new electronic ignition was paired with the revised top end, and a redesigned pipe was added to interface with the reconfigured ATAC and boost low-end performance. An all-new airbox offered deeper breathing through an enlarged inlet, and a new air filter featured denser foam and an updated sealing surface to reduce the chance of a filter-related failure.

Trick features like the CR’s fully removable rear subframe helped make maintenance easier than many of Honda’s competitors. Photo Credit: Honda

Trick features like the CR’s fully removable rear subframe helped make maintenance easier than many of Honda’s competitors. Photo Credit: Honda

In the bottom end, Honda revised the shift forks and engagement dogs of the five-speed transmission for increased durability and improved shifting feel. The new parts offered an updated heat treatment, and the spindle was hardened to allow for easier sliding of the internal components. The ratios of all five gears and the 14/51 final drive ratio remained unchanged from 1984.

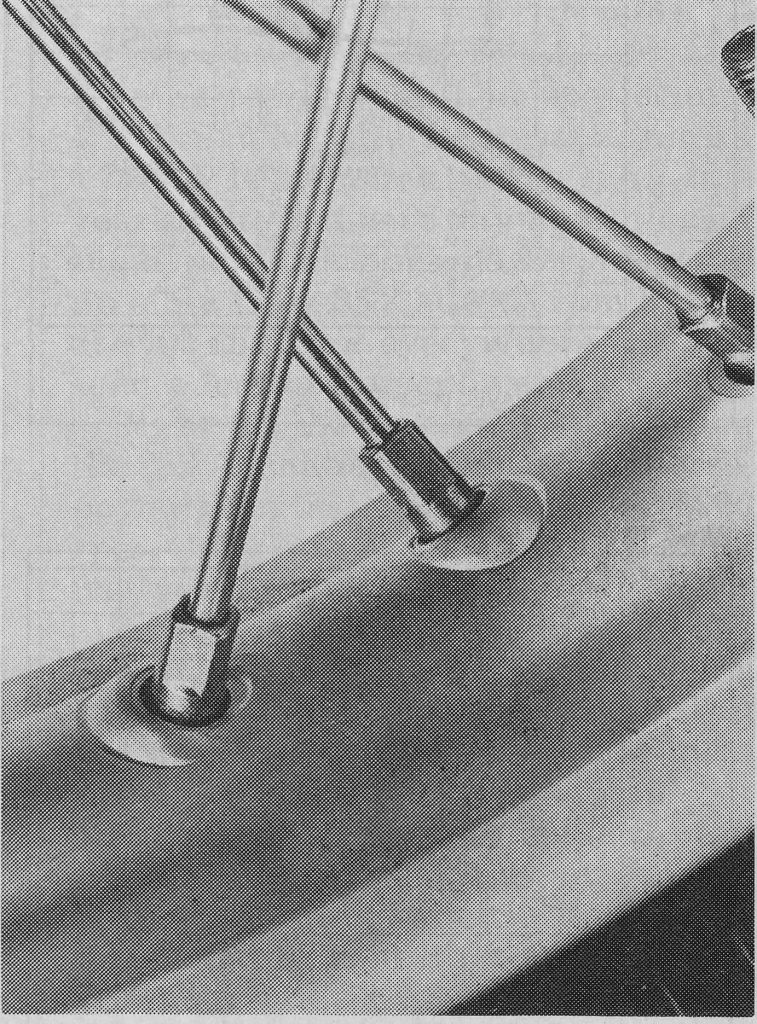

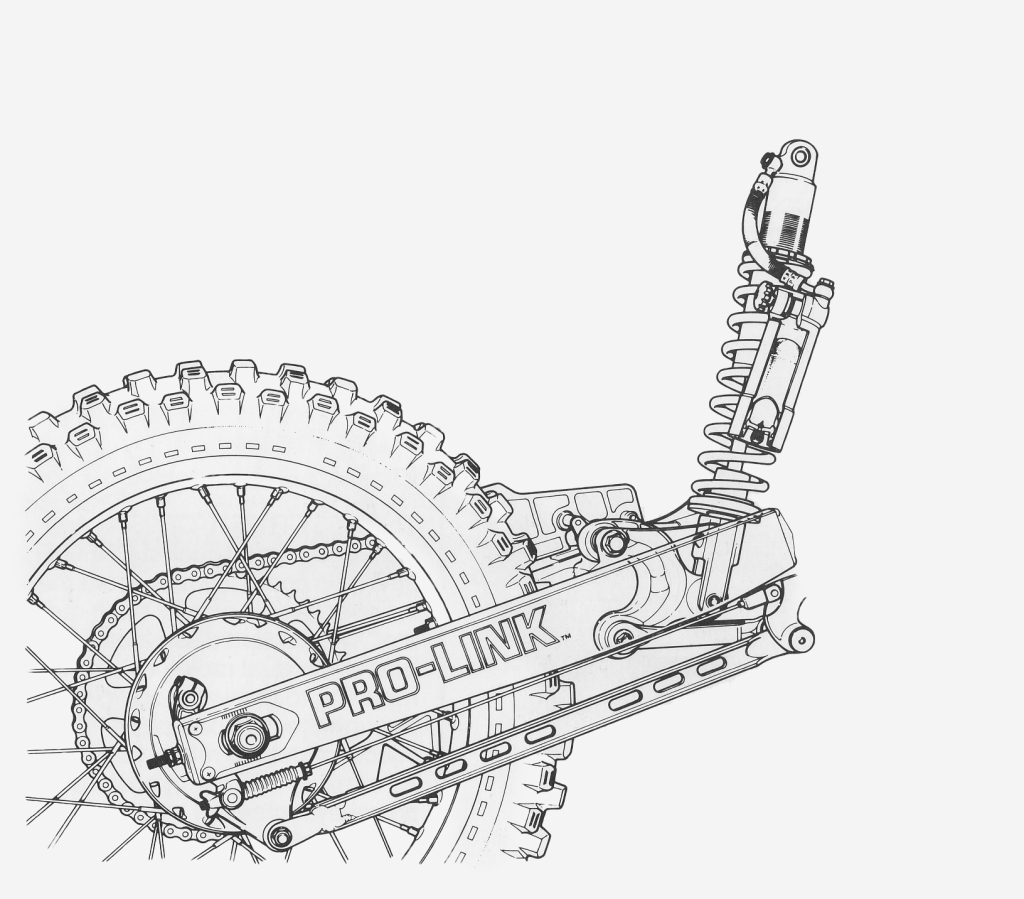

An all-new Pro-Link linkage featured upgraded bearings and a more progressive curve for improved action. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new Pro-Link linkage featured upgraded bearings and a more progressive curve for improved action. Photo Credit: Honda

On the chassis front, the CR was just as “all-new” for 1985. In 1984, the CR250R had been a turn-shredding fool that craved the inside line but shook its head like a soggy dog when coming down from speed. Riders loved the turning, but many pilots found its aversion to bumpy, high-speed straights more than a bit disconcerting.

An all-new 36mm Keihin “flat-slide” carburetor offered improved throttle response, easier idle adjustment, and a 20% reduction in weight over the round slide Keihin PE mixer used in 1984. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1985, Honda’s engineers spec’d an all-new chassis that they hoped would tone down the CR’s violent fits of schizophrenia without neutering its remarkable turning. This was no small order, but the CR’s developers felt they could find the perfect balance of handling traits by strengthening the bike’s frame, rejiggering its weight balance, altering its geometry, updating its suspension, and fine-tuning its riding position. The new frame remained crafted out of tough chromoly steel in a semi-double cradle configuration that pushed the steering head forward 10mm and repositioned it 5mm lower. The wheelbase was also altered to be 0.2 inches longer. The rake was increased slightly from 26.7 degrees to 27.5 degrees, and the chassis was strengthened in critical areas to reduce flex. The swingarm pivot was repositioned 0.4 inches forward and the front downtube was changed from round to square tubing for increased strength. The lower frame crosspipes were modified to provide additional resistance to torsional flex, and the footpeg brackets and head stay were changed to a forged steel construction for additional strength. The new chassis retained the trick removable subframe the CR250R had been offering since 1983, and this works-like feature greatly simplified the servicing of the machine.

1984 Supercross champion Johnny O’Mara could make the all-new CR look considerably faster than it really was. Photo Credit: Honda

1984 Supercross champion Johnny O’Mara could make the all-new CR look considerably faster than it really was. Photo Credit: Honda

In the rear, the new chassis featured a total revamping of the CR’s proven Pro-Link single-shock suspension system. An all-new linkage moved to a flatter progression curve and featured upgraded bearings throughout. All the main linkage pivots were changed from bushings to needle roller bearings to provide a smoother and more precise action. The Heim-type mounting point for the shock was also upgraded to reduce the play and annoying “clunk” riders felt when loading or unloading the suspension. An all-new extruded aluminum box-section swingarm featured a tapered design for the best combination of weight savings and strength.

All-new bodywork for 1985 slimmed the CR’s midsection, lowered the tank, and made moving forward in turns easier. Photo Credit: Honda

All-new bodywork for 1985 slimmed the CR’s midsection, lowered the tank, and made moving forward in turns easier. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda’s elder statesman Bob Hannah rekindled a bit of the old Unadilla magic in 1985 by racing his factory RC250 to the USGP first moto win. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Honda’s elder statesman Bob Hannah rekindled a bit of the old Unadilla magic in 1985 by racing his factory RC250 to the USGP first moto win. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Paired with the redesigned Pro-Link was an all-new Showa remote reservoir shock. The new damper featured longer shaft travel, all-new valving, increased oil capacity, a 4mm larger internal piston, and an “automatic temperature control valve” to fight fading. The new shock added 0.6 inches of additional travel for a total of 12.6 inches with 18 available settings for compression and 21 available adjustments for rebound control.

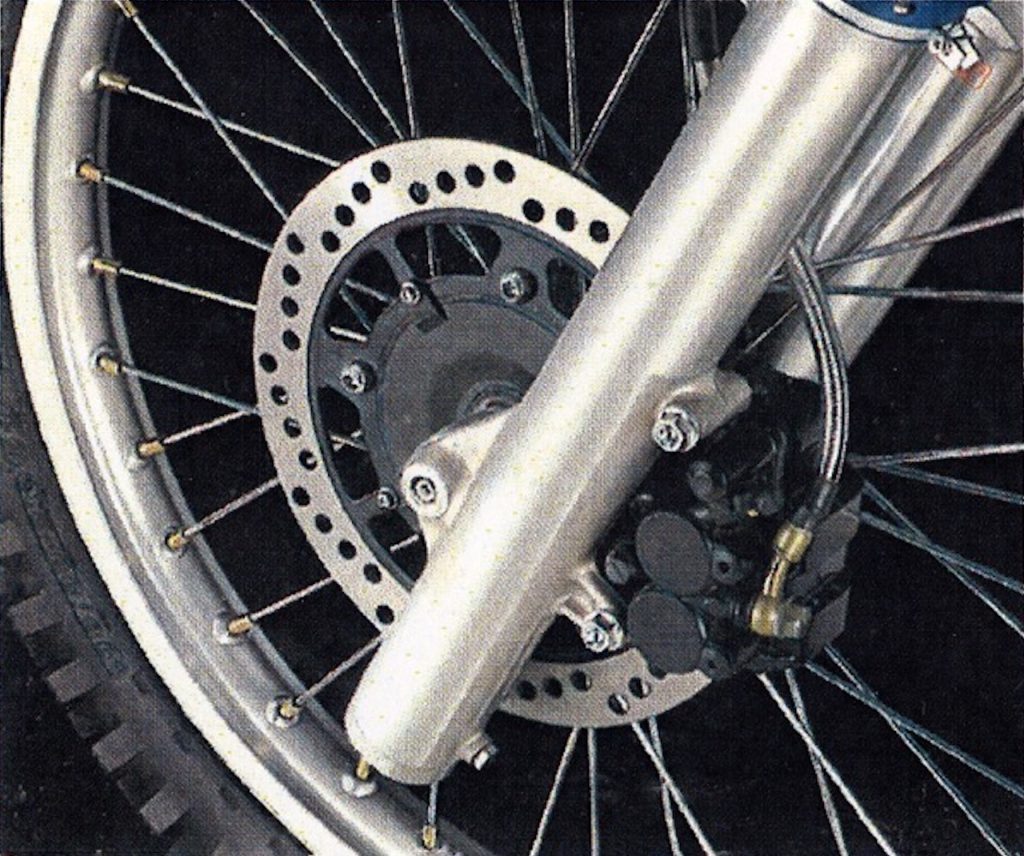

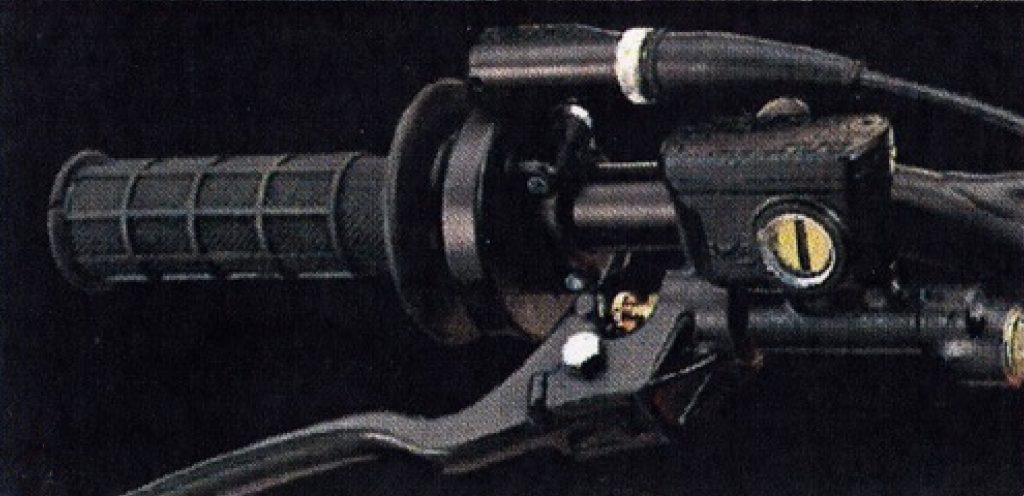

The CR’s dual-piston Nissin front binder offered the most power, best feel, and least need for maintenance in the 250 division. Photo Credit: Honda

The CR’s dual-piston Nissin front binder offered the most power, best feel, and least need for maintenance in the 250 division. Photo Credit: Honda

Up front, the CR250R continued to employ a set of 43mm conventional Showa damper-rod forks. At this point in time, Showa’s revolutionary works-type cartridge damping system was still a year away from its debut on the CR250R. Without the fancy wave washers, the CR had to make do with relatively minor upgrades in 1985. Visually, they looked quite different due to the switch from black to blue for the fork boots. This mimicked the look of the works Hondas in 1984 and better matched the seat and other graphics in ’85. Fork boots aside, the Showa components were largely unchanged, except for updates to the valving in 1985. Total travel remained at 12 inches with 12 external adjustments available for compression damping and a Schrader valve on each fork cap for adjusting air pressure.

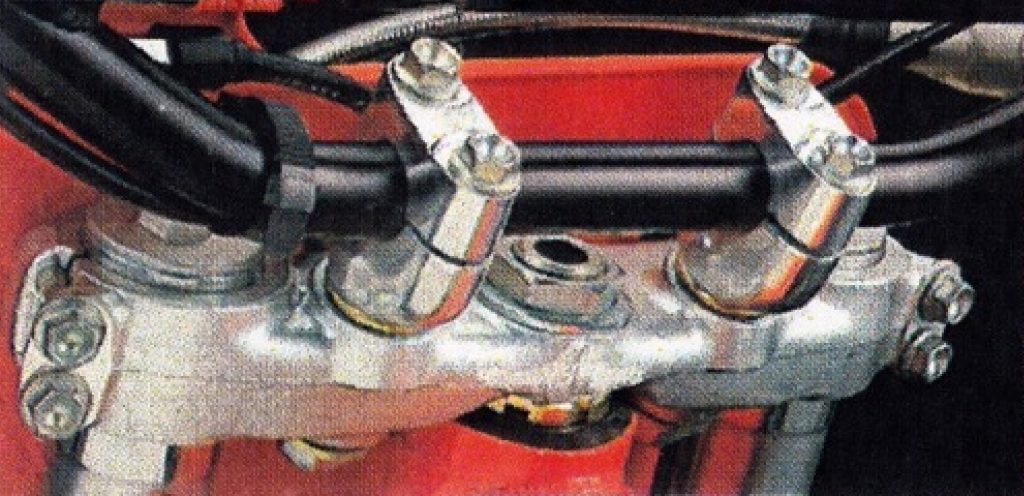

Rubber-mounted clamps helped quell vibration on the new CR. Photo Credit: Honda

Rubber-mounted clamps helped quell vibration on the new CR. Photo Credit: Honda

Visually, the most significant update to the ‘85 CR250R was its redesigned bodywork. Aside from the front fender and front number plate, all of the CR’s bodywork was significantly updated for 1985. The all-new tank was sleeker, slimmer, and slightly smaller with a reduction in capacity from 2.1 gallons to 1.9 gallons. The new tank was narrower at the seat/tank junction and flared out less at the top allowing easier rider movement to weight the front of the machine in turns. The redesigned shrouds were attractive, slightly larger, and featured enlarged vents to aid cooling. The new seat was shorter, with a revamped shape designed to interface with the smaller tank. Redesigned side plates offered a bit more room for numbers and an all-new rear fender was wider and a bit less tall for additional roost protection and improved aesthetics. The iconic Honda wing graphic remained on the shrouds, but its appearance was altered with a switch from its traditional yellow to a new red, white, and blue motif that worked very well with the CR’s new blue fork boots and works bike styling.

The CR250R’s all-new chassis continued Honda’s run of sharp handlers. If the track was tight, nothing in the class could out-carve the razor-sharp CR. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The CR250R’s all-new chassis continued Honda’s run of sharp handlers. If the track was tight, nothing in the class could out-carve the razor-sharp CR. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The 1984 CR250R’s brakes were some of the best in the business, but even Honda fanboys had to admit that the rear drum’s annoying habit of squealing when hot was not a selling point. In 1985, Honda upgraded the rear drum by replacing the magnesium shoes used in ’84 with aluminum replacements they claimed would stop the constant squealing. Up front, the CR continued to offer the only dual-piston disc stopper in the class, and it once again promised to deliver works bike power and feel. All-new wheels for 1985 featured larger spokes and beefed-up axles to prevent the wheel issues some hard-ridden CRs experienced in 1984. Lastly, an all-new three-piece throttle housing promised to make servicing the throttle and replacing the cable easier in 1985.

Largely unchanged from the year before, the CR’s 43mm damper-rod Showa forks continued to be mid-pack performers. Softy sprung, harsh in the midstroke, and prone to bottoming, they benefitted greatly from some aftermarket assistance. Photo Credit: Honda

Largely unchanged from the year before, the CR’s 43mm damper-rod Showa forks continued to be mid-pack performers. Softy sprung, harsh in the midstroke, and prone to bottoming, they benefitted greatly from some aftermarket assistance. Photo Credit: Honda

On the track, the all-new CR250R proved to be a significant downgrade in the minds of most testers. In the search for more torque and improved reliability, Honda’s engineers neutered the CR’s most significant performance advantage, and that made it a hard sell to racers expecting an improved version of the rocket-fast ’84 machine. Unlike the old engine, which hit hard in the midrange and pulled to the moon, this new version was more Massey Furguson than Ferrari.

The CR’s all-new motor transformed the red machine from a high-RPM screamer into a low-RPM torquer. The revamped ATAC motor was snappy off the bottom and easy to ride but utterly lacking in the top-end pull that fast guys loved in 1984. With some aftermarket upgrades, the new motor was a rocket, but in stock condition, it lacked the firepower to run at the front. Photo Credit: Honda

The CR’s all-new motor transformed the red machine from a high-RPM screamer into a low-RPM torquer. The revamped ATAC motor was snappy off the bottom and easy to ride but utterly lacking in the top-end pull that fast guys loved in 1984. With some aftermarket upgrades, the new motor was a rocket, but in stock condition, it lacked the firepower to run at the front. Photo Credit: Honda

The revamped ATAC mill put all its ponies down low with tons of grunt and virtually no rev. It was an absolute tractor out of the hole with instant snap that rocketed the CR out of tight turns but once it pulled past the midrange, the party was all but over. Just about the point where the old machine was getting started this new CR was ready to throw in the towel. If you tried to rev it out, it just made noise and lost speed like you had sucked a chipmunk into the carb. It was all torque and no rev, and most racers felt it was a serious downgrade from the year before. Some novices liked the grunty delivery but there was no getting around the reality that the new motor was slower.

Motocross Action set up a back-to-back comparison of a brand new 1984 and 1985 CR250R and the results showed the ’85 machine to be superior in every category but one. The new bike was more comfortable, stopped better, turned sharper, and came out of the hole harder, but once the bikes hit third gear, the older machine walked away every time. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Motocross Action set up a back-to-back comparison of a brand new 1984 and 1985 CR250R and the results showed the ’85 machine to be superior in every category but one. The new bike was more comfortable, stopped better, turned sharper, and came out of the hole harder, but once the bikes hit third gear, the older machine walked away every time. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

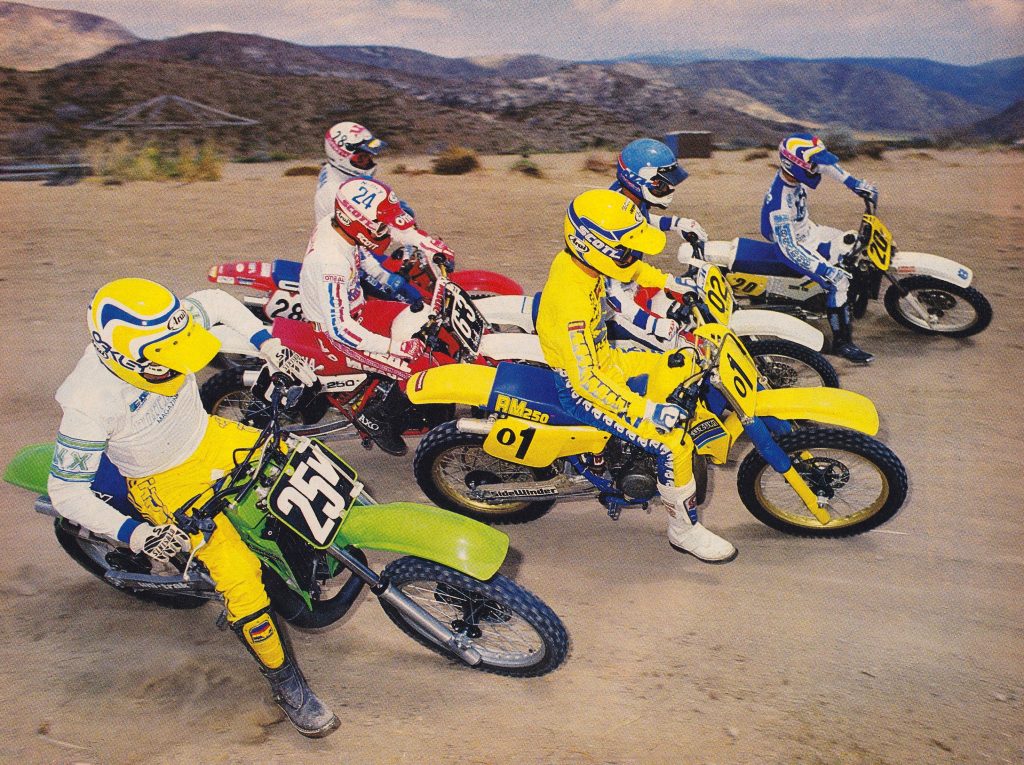

When MXA pitted a brand new ’84 CR250R against the revamped ’85, the old machine dusted it every time. Unfortunately for the CR, the outcome was not any better when facing its 1985 rivals. The ’85 Yamaha offered a similar grunt down low but romped on the CR in the midrange and pulled farther on top. The Kawasaki lacked the low-end punch of the CR and YZ but made up for it with tons of midrange and a strong pull on top. Even the Suzuki, with the least exciting powerband of the bunch, was more than a match for the CR. For play riding and novice level racing it was a good motor, but anyone looking to make it big on the track was likely to want a few motor upgrades.

In the 1985 250 sweepstakes, there were a ton of contenders but no obvious victors. All the machines were flawed in one way or another, but most testers seemed to feel Suzuki’s RM250 did the best job of delivering a race-winning package. Credit: Dirt Bike

In the 1985 250 sweepstakes, there were a ton of contenders but no obvious victors. All the machines were flawed in one way or another, but most testers seemed to feel Suzuki’s RM250 did the best job of delivering a race-winning package. Credit: Dirt Bike

On the handling front, the CR remained the shredder of the 250 division. The new chassis carved up turns with excellent front wheel traction and superb steering response. The Honda loved to dive to the inside and seemed to be an extension of the rider’s thoughts when it was time to change direction. The new tank and seat made it even easier to get forward in the turns and virtually everyone found the CR comfortable and easy to move around on. The bike felt light and nimble on the track and easy to throw around in the air. On a tight track, the CR was King, but open things up and the King turned into a pauper.

Excellent grips, smooth controls, and sturdy components helped give the CR a high-quality feel. Photo Credit: Honda

Excellent grips, smooth controls, and sturdy components helped give the CR a high-quality feel. Photo Credit: Honda

At speed, the CR was like a cat on a hot tin roof dancing, hopping, and weaving. Despite several chassis changes aimed at toning it down, the 1984 model’s epic headshake remained, and the bike could be a real handful if the track was fast and rough. Once the bars started dancing, the rider was largely along for the ride. Gripping the tank with your knees and holding on for dear life were the only real options. If you were tired and pumped up, this death wobble could result in quite a few brown trouser moments as the CR tried to eject its pilot like a honky-tonk mechanical bull. This handling compromise was perfect for Supercross where the CR’s aggressive turning and gonzo low-end torque allowed riders to shred the track and conquer tricky jumps out of turns. Outdoors, however, its short powerband and wayward high-speed manners were far more of a tough sell. Longtime Honda pilots became accustomed to its often-schizoid behavior, but riders jumping on the CR from other brands were frequently left wide-eyed and trembling as they exited the track.

An updated airbox and air cleaner for 1985 offered increased airflow and improved sealing. Photo Credit: Honda

An updated airbox and air cleaner for 1985 offered increased airflow and improved sealing. Photo Credit: Honda

On the suspension front, the CR was the same mid-pack performer it had been in 1984. The largely unchanged 43mm Showa conventional forks continued to deliver a decent ride with a touch of harshness in midstroke. The initial travel was a bit soft, and many riders did not care for the sudden ramp-up in resistance its valving provided. The stock springs could be ridden by most average-sized pilots, but fast guys needed stiffer coils. Serious sky shots bottomed them out harshly and even less aerial prone pilots felt they worked better with a bit more oil in each leg and an upgrade to the springs. For pros and Guy Cooper wannabes, the hot setup in 1985 was a set of stiffer springs from ATK or White Bros. and a Simons Anti-Cav kit to smooth out the damping.

Oingo Boingo: The all-new rear suspension for 1985 delivered discouraging performance on the track. The shock kicked in the rough, bottomed out on big hits, and continued to suffer from premature fading despite the new shock’s additional oil capacity. Photo Credit: Honda

Oingo Boingo: The all-new rear suspension for 1985 delivered discouraging performance on the track. The shock kicked in the rough, bottomed out on big hits, and continued to suffer from premature fading despite the new shock’s additional oil capacity. Photo Credit: Honda

In the rear, the new Pro-Link turned out to be severely disappointing. Fighting fade had been a major focus of the ’85 upgrades but the new larger shock continued to lose most of its damping control when hot. When fresh, it was prone to kicking in the rough and that unruly behavior only got worse once the shock heated up. It hated square-edged bumps and smacked the rider in the rear out of choppy corners. The action was so poor at times that it forced the rider to back off the throttle to keep the rear of the machine under control. It slammed to the stops on big hits and wallowed in the whoops. This pogo-like performance only exacerbated the Honda chassis’ high-speed unpredictability and certainly contributed to its white-knuckle-inducing fits of the shakes.

The updated CR was quick from corner to corner, but if the track was wide open and fast, then the Honda’s pilot needed a bit of luck and a very fast left foot to keep its rivals at bay. Photo Credit: Honda

The updated CR was quick from corner to corner, but if the track was wide open and fast, then the Honda’s pilot needed a bit of luck and a very fast left foot to keep its rivals at bay. Photo Credit: Honda

Unfortunately, unlike the forks, a simple spring swap and some oil fiddling were not enough to get the CR’s cantankerous shock up to snuff. Getting the shock re-valved helped sort its damping but did very little for its fading problem. The stock shaft was also not hard coated and prone to excessive wear. For serious racers, the best fix was to replace the Showa damper with an aftermarket unit. An Õhlins shock would set you back $419 in 1985 ($1251 in 2025 dollars) but for serious racers, it was a worthwhile investment.

The O’Show started his title defense with a victory at San Diego but was not able to outduel Kawasaki’s Jeff Ward for the 1985 Supercross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

The O’Show started his title defense with a victory at San Diego but was not able to outduel Kawasaki’s Jeff Ward for the 1985 Supercross title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action.

In the end, Honda’s success rate for the new CR turned out to be a bit of a mixed bag in the minds of most consumers and magazine editors at the time. First up on the home run list were the CR’s new bodywork and exceptional build quality. The new layout was unanimously praised for its looks and feel and the quality of materials was evident in everything you touched, twisted, or looked at. Riders loved the comfy saddle, excellent grips, well-shaped levers, silky throttle, and durable graphics. The front brake was the best in the business and the CR was well-thought-out and easy to work on. The new ATAC was much easier to service and the removable rear subframe made swapping out that grim shock much less of a chore. The new flat-slide carb delivered snappy performance and made adjusting the idle a snap. The CR felt tight when new and stayed looking and feeling that way longer than its competition.

The nimble CR250R was an excellent jumper in 1985. Photo Credit: MotoCross

The nimble CR250R was an excellent jumper in 1985. Photo Credit: MotoCross

Reliability was a serious black eye in 1984, but the new CR turned that weakness into a plus in 1985. The new motor was far slower, but it also proved exponentially more reliable. The revamped engine no longer cracked pistons and spun crank bearings and the transmission held together when ridden aggressively. Piston and ring wear was much better and the top end no longer tried to eject itself out the exhaust port once a month. As long as you kept the ATAC clean, ran good oil, checked the top end regularly, and cleaned the air filter, the CR was as reliable as any high-performance two-stroke could be expected to be.

Honda’s all-new ’85 CR250R cured the reliability issues that plagued the ’84 machine but lost most of the pizzazz that riders loved the year before. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda’s all-new ’85 CR250R cured the reliability issues that plagued the ’84 machine but lost most of the pizzazz that riders loved the year before. Photo Credit: Honda

On the “ground out to first base” list for 1985 were the CR’s butter-soft stock chain and sprockets, quick-wearing rear brake shoes, complete lack of revs, fade-o-matic rear shock, and utter aversion to high speeds. Many riders still loved the CR for its looks, feel, and potential, but its lack of horsepower and grim rear shock were hard to ignore.

In the end, the 1985 CR250R turned out to be a beautiful but flawed racer. Modified ’85 CRs were some of the fastest bikes on the track, but in stock condition, they fell short of the mark for most serious racers. With a few upgrades, the ’85 CR250R could be a world beater, but in stock condition, it was an unfinished product. With its razor-sharp manners, light feel, and torquey motor the stock CR250R could be a lot of fun, but if going fast on a track was your number one priority, the machine needed a bit more polish and performance to make it to the front.