For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new CRF250R for 2004.

All-new from the ground up, Honda’s first CRF250R proved so popular that Japan had to add a second production run to meet demand in 2004. Photo Credit: Honda

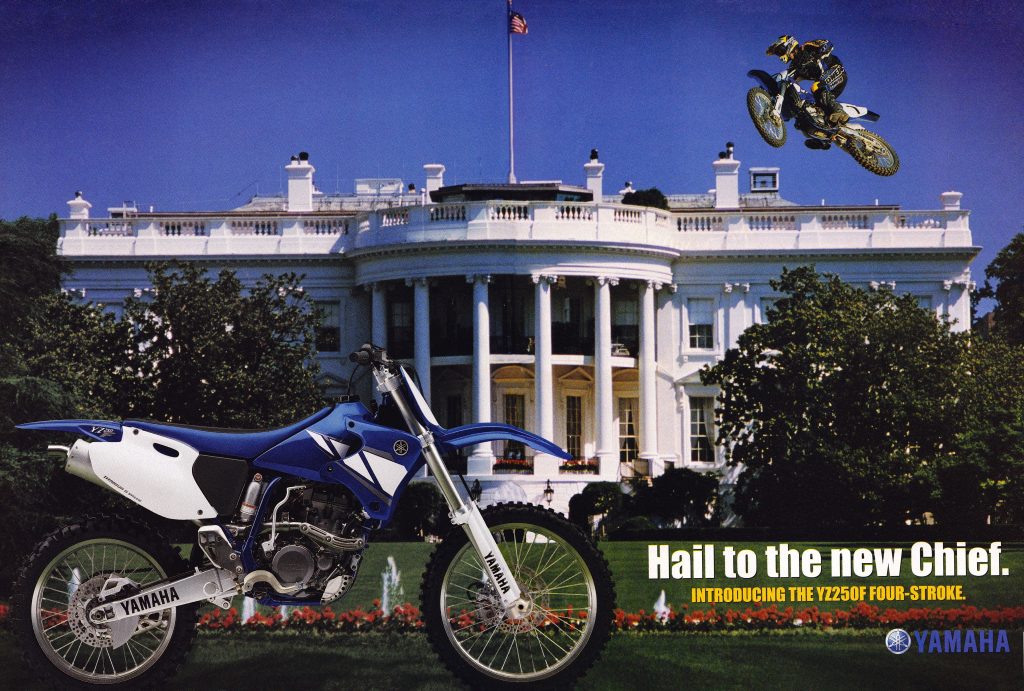

In 1997, Yamaha fired the shot heard around the motocross world with the news that they were releasing a production version of the works YZM400F four-stroke that carried Doug Henry to victory in the Las Vegas Supercross season finale. The production YZ400F turned out to share very little with Henry’s ultra-trick YZM, but its performance and popularity were no less revolutionary.

Before the introduction of Yamaha’s first YZ250F in 2001, no one outside of an XRs Only message board took racing a 250 four-stroke seriously. Once again, Yamaha had caught the industry (and AMA) napping as the little blue revver rewrote the rules of 125 racing in America. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Before the introduction of Yamaha’s first YZ250F in 2001, no one outside of an XRs Only message board took racing a 250 four-stroke seriously. Once again, Yamaha had caught the industry (and AMA) napping as the little blue revver rewrote the rules of 125 racing in America. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 2000, Yamaha once again shocked the industry by announcing the release of another all-new four-stroke motocross machine – the class-redefining YZ250F. Yamaha’s high-revving 250F proved far more controversial than the 400F had been due to the significant displacement and torque advantage it held over the 125s it was allowed to compete against. The all-new YZ250F was far heavier than a 125 and still prone to the traditional four-stroke bog and flame-out bugaboos, but if you could keep from stalling it, it was a tremendous advantage.

In 1997, Honda introduced the first production alloy perimeter frame to motocross. While incredibly trick, the first-generation aluminum frame suffered in comfort, handling, and feel compared to the steel frames it replaced. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1997, Honda introduced the first production alloy perimeter frame to motocross. While incredibly trick, the first-generation aluminum frame suffered in comfort, handling, and feel compared to the steel frames it replaced. Photo Credit: Honda

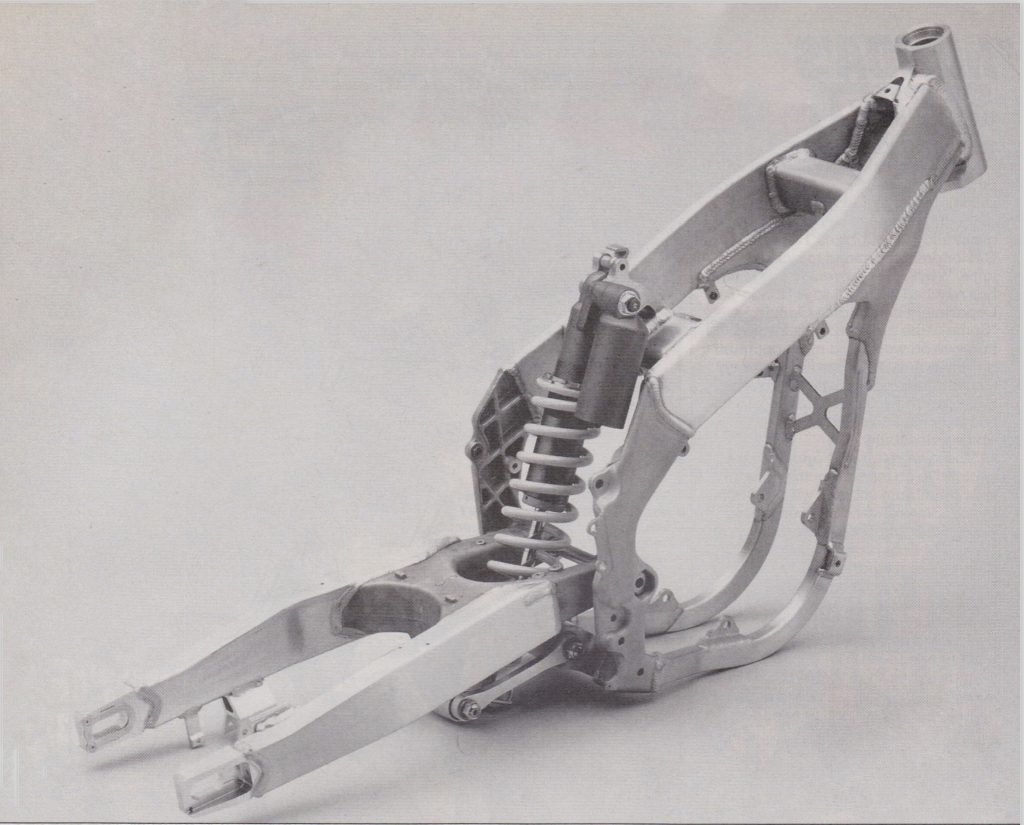

The all-new CRF250R introduced the fourth generation of Honda’s alloy frame. The new frame shortened and slimmed the width of the main spars and beefed up the swingarm pivot plates to increase comfort and optimize the chassis’ flex characteristics. Photo Credit: Honda

Remarkably, it would take Yamaha’s competitors a full five years to introduce a response to the original YZ400F. In 2002, Honda finally fired back with a four-stroke 450 of their own, the original CRF450R. Honda’s new big-bore addressed many of the complaints riders had with the YZ-F by simplifying starting, lowering weight, and reducing the motor’s prodigious compression braking. The new Honda was not as fast as the YZ426F, but it hiccupped less, felt lighter, and started much easier. The all-new CRF450R proved an incredible hit with consumers with the red machines flying out of Honda showrooms as fast as Big Red could build them.

Like the CRF450R, the all-new CRF250R employed a lightweight, short skirt “slipper” piston. Photo Credit: Honda

While the CRF450R and KTM’s 525SX provided the YZ426F with legitimate competition in 2002, the 125/250F class remained the sole domain of the high-revving YZ250F. Ultra-talented pilots like James Stewart could still outduel the Yamaha, but the writing was clearly on the wall for the traditional 125. Unless the AMA rewrote the rules to add displacement to the 125s or took steps to reduce the performance of the four-strokes, the 125s days were numbered.

With its automatic decompression system and handlebar-mounted “hot start” trigger, the CRF was an easy and reliable starter. Photo Credit: Honda

In 2004, competition finally came to the 250F division with the introduction of three all-new competitors to Yamaha’s YZ250F. To fast-track the development of a YZ-F competitor, Suzuki and Kawasaki teamed up to create an all-new machine that could be sold through both dealer networks. The new machine utilized a Suzuki-developed motor housed in a Kawasaki chassis. Kawasaki handled the final assembly with the new KX250F and RM-Z250 sharing 99% of their components aside from a swap in color and slight deviation in the shape of each machine’s radiator shrouds.

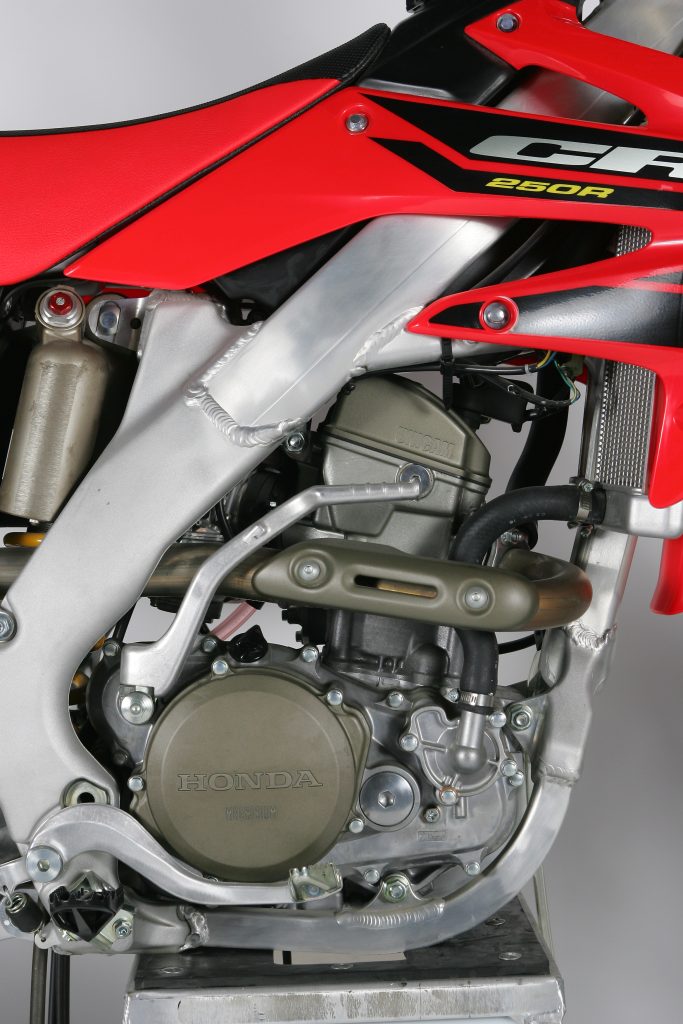

With its single overhead cam and dual-chamber oil system, the CRF250R was the most unique engine in the 2004 250 four-stroke division. Photo Credit: Honda

Like the YZ250F, the new Kawazuki twins relied on a short-stroke dual-overhead-cam design that allowed for high revs and quick-building power. Unlike the five-valve Yamaha, the twins chose to rely on a traditional four-valve head (two intake and two exhaust) to get fuel and air in and exhaust out. To reduce weight, the twins eschewed the Yamaha’s external oil tank in favor of a new “semi-dry-sump” configuration. The Suzuki-designed motor stored all its oil internally, which limited capacity but allowed the engineers to make the motor lighter and more compact. The semi-dry-sump design placed the crank very low in the chassis for optimal handling and stored most of its oil in the upper transmission compartment.

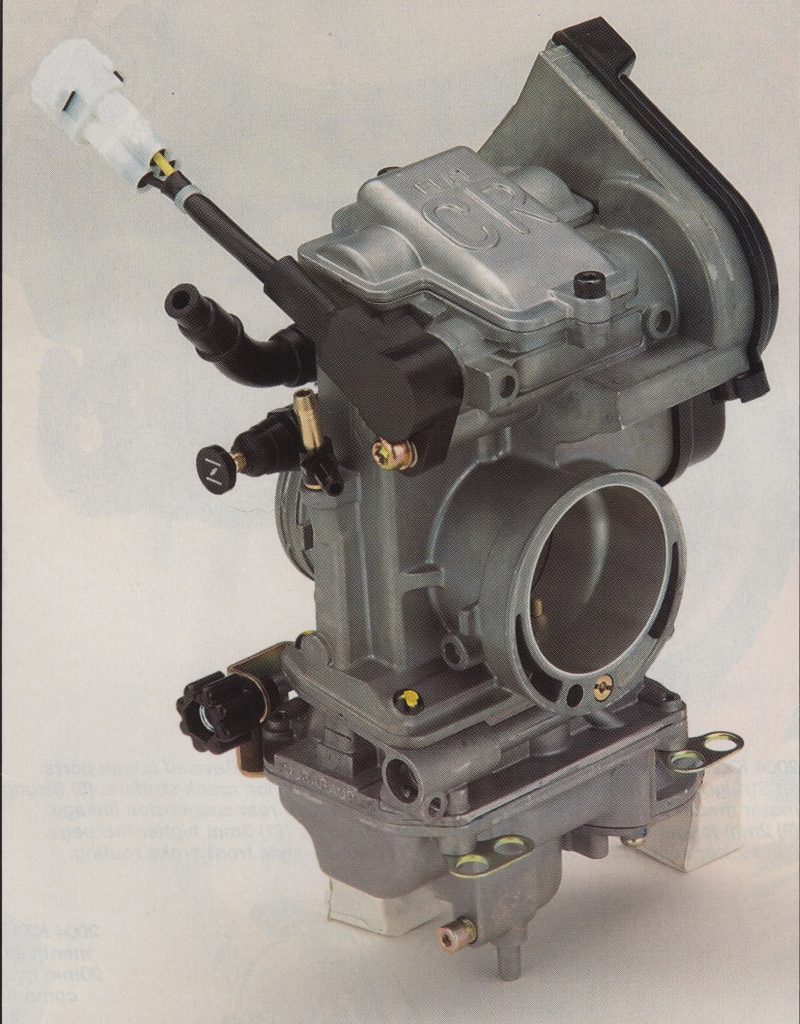

Before the introduction of fuel injection, Keihin’s road-race-inspired FCR carburetor was the gold standard of high revving four-stroke performance. A 37mm FCR provided the smaller CRF with crisp and responsive performance. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Before the introduction of fuel injection, Keihin’s road-race-inspired FCR carburetor was the gold standard of high revving four-stroke performance. A 37mm FCR provided the smaller CRF with crisp and responsive performance. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

After the success of the CRF450R, Honda was anxious to get their slice of the 250 four-stroke pie, and in 2004 they finally unveiled their entry into the 250F sweepstakes. All-new from the ground up, the 2004 CRF250R featured the first use of Honda’s fourth-generation aluminum frame, redesigned bodywork, and an all-new 249cc four-stroke power plant. Like the CRF450R, the new CRF250R employed a very different motor design than its Japanese competitors. Instead of relying on a traditional DOHC layout, Honda’s engineers focused on making the CRF motor as compact as possible by choosing a smaller and lighter single-overhead-cam layout. Dubbed the “Unicam” by Honda, the CRF250R head relied on a single carburized camshaft to activate two 31mm titanium intake valves and two 26mm steel exhaust valves. The use of titanium for the intake valves allowed Honda to employ smaller valve springs to keep the height of the motor as low as possible. A 12.5:1 compression “slipper” piston kept reciprocating mass low and an ultra-hard Nikasil liner provided excellent durability and optimal heat dissipation.

An all-new airbox provided the CRF250R with improved breathing over the CRF450R design. Photo Credit: Honda

Another unique feature of the CRF motor was its use of separate oils for the motor and transmission. By separating the transmission oil from the other engine components, Honda felt they could use the ideal lubricant for each application, reduce the size of the oil pump, and diminish engine wear by preventing particles sloughed off by the clutch and transmission from making their way into the motor’s top end. While these were significant benefits, the CRF carried much less oil in reserve than Yamaha’s 250F, so it was imperative to keep a close eye on oil usage and stick to a very strict maintenance schedule.

The CRF’s stainless steel and alloy exhaust system debuted the new FIM-mandated closed-end cap for 2004. To Honda’s credit, this was the least obnoxious of the stock exhausts in the 250F division. Photo Credit: Honda

A 37mm Keihin FCR carburetor handled mixing duties and featured a Throttle Position Sensor (TPS) to optimize motor response and four rollers built into the flat slide to provide a light and smooth pull at the throttle. A gear-driven counter-balancer powered the water pump and quelled most of the motor’s vibration. This was a nice feature not found on the new Kawazuki twins. As with the CRF450R, an automatic decompression system was built into the kickstarter and the new Honda did not require an elaborate starting drill to get the fun started. The CRF’s exhaust header was crafted out of lightweight stainless steel for durability and the rebuildable muffler was constructed out of aluminum to save weight. A close-ratio five-speed transmission and eight-plate manual clutch finished off the all-new motor package. All these features added up to a very light 52.7lb dry weight for the motor, only pounds heavier than the CR250R two-stroke mill.

No Monkey butt: With its excellent shape, comfy foam, and non-slip cover, the CRF’s seat was the unanimous pick for the best stock motocross saddle of 2004. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1997, Honda introduced the first generation of their aluminum frame to much fanfare. The all-new ’97 CR250R looked like an exotic works bike from Japan but often performed like an unfinished product. The first-gen frame was built with reliability as a cornerstone of its design and this proved detrimental to many aspects of its performance. The overbuilt chassis acted like a tuning fork transmitting inordinate amounts of vibration back to the rider and most of the CR’s legendary handling was no longer apparent. Riders snapped up the ultra-trick machines in droves, but many found life with the alloy chassis did not live up to the hype.

Providing Renthal’s highly-regarded 971 alloy bars as standard equipment was an excellent value-add to the new CRF250R. Photo Credit: Honda

In 2000, Honda introduced the second generation of their alloy chassis on the all-new CR125R and CR250R. The new frames dialed back the rigidity and slimmed down the ergonomics considerably and offered improved ergonomics and handling over the bulky first-gen designs. They were still a bit wide and transmitted too much vibration, but everyone agreed they were a huge step in the right direction for the red machines.

Honda’s unique Unicam design allowed the engineers to keep the height and weight of the CRF motor extremely low. At 52.7 pounds, the CRF250R engine clocked in at only two pounds more than the existing CR250R two-stroke mill. Photo Credit: Honda

By 2002, Honda was beginning to get a firm handle on the complexities of alloy chassis design. The all-new CR125R, CR250R, and CRF450R featured the third generation of Honda’s alloy chassis and virtually everyone agreed that the bugs and compromises found on earlier alloy CRs were no longer apparent. The third-generation alloy CRs offered excellent ergonomics, sharp handling, minimal vibration, and an ultra-light feel. The all-new CRF450R had some riders who questioned its turning prowess, but everyone loved its comfy chassis and rock-solid stability.

Nate Dog: Honda’s four-stroke ace Nathan Ramsey was picked to race the all-new CRF250R indoors and out. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Nate Dog: Honda’s four-stroke ace Nathan Ramsey was picked to race the all-new CRF250R indoors and out. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

With the all-new 2004 CRF250R, Honda was set to unveil the fourth generation of their alloy frame design. As with previous updates, the gen four redesign was set to improve handling, ride quality, and comfort by adjusting the metallurgy, refining the construction methods, and reshaping and repositioning the major frame elements. As with the previous generation frame, Honda’s new “type four” chassis used a mixture of castings and extruded elements to make up its construction. Both main frame spars were made shorter and slimmer in cross-section with varying thickness to optimize the flex characteristics of the chassis. The frame’s castings were both smaller and lighter than the old frame design with large swingarm pivot plates added for strength. The new frame offered improved rigidity at the steering head but more flex at other points of the chassis. This was done to optimize steering precision while also improving ride comfort.

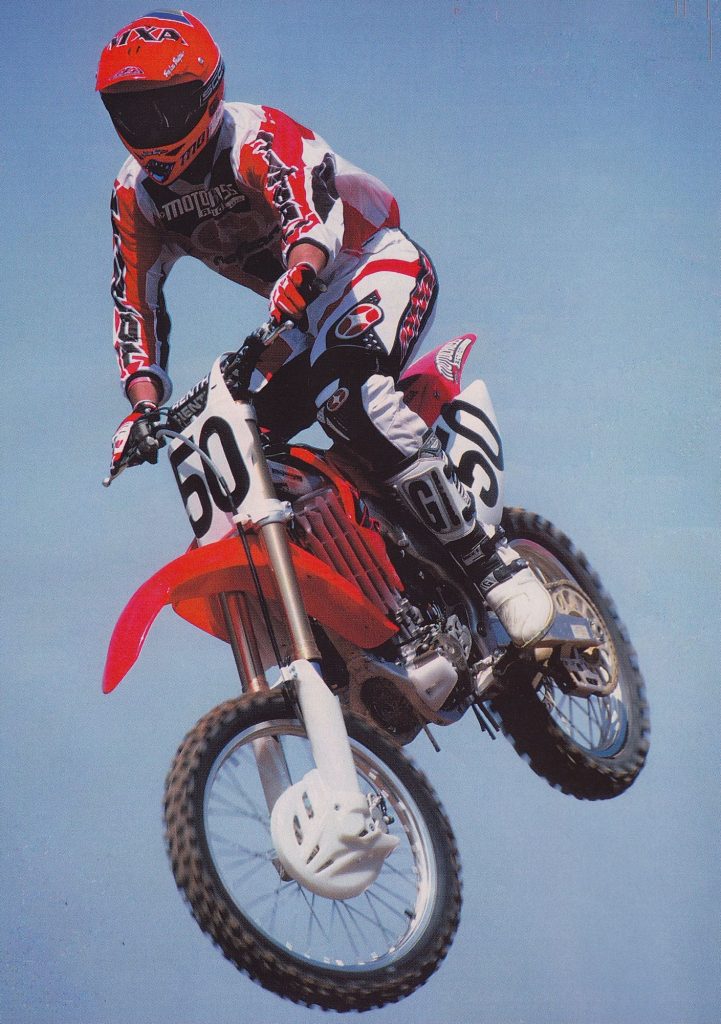

While the all-new CRF250R was not the fastest bike in the class, talented riders like 7-time Supercross champ Jeremy McGrath could turn incredibly fast laps on the high-revving thumper. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While the all-new CRF250R was not the fastest bike in the class, talented riders like 7-time Supercross champ Jeremy McGrath could turn incredibly fast laps on the high-revving thumper. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Paired with the all-new frame was revised bodywork that slimmed the CRF’s lines and improved comfort. The overall look was similar to the CRF450R, but all the bodywork aft of the front fender was all-new. The new sideplates offered cleaner lines and improved airflow and an all-new seat featured a flatter profile and trick non-slip cover. In a first for Honda, the CRF250R received Renthal’s highly-regarded 971 alloy bars as standard equipment. This was a nice touch that added value to Honda’s new $5799 super thumper. The front clamps were rubber mounted for comfort and offered three available bar positions to tailor the ergonomics to different-sized riders. Both the front and rear rotors were 240mm in diameter with a powerful twin-piston Nissin caliper up front and a “works style” integrated rear master cylinder in the rear.

The 47mm Showa Twin-Chamber forks on the CRF250R shared most of their internals with the two-stroke CR250R and both machines delivered very good fork performance. Some riders preferred the smoother feel of the Yamaha’s 48mm KYBs, and fast guys felt the Showas needed stiffer springs, but both forks worked very well without the need for serious modification. Photo Credit: Honda

On the suspension front, the CRF250R shared most of its components with its two-stroke 250 sibling. Up front, the CRF250R featured a set of 47mm Showa twin-chamber cartridge forks offering 12.4 inches of travel. The forks were externally adjustable for compression and rebound damping with 16 selectable settings available for both adjustments. In the rear, the CRF used a single Showa damper bolted to an all-new Pro-Link linkage. The damper offered external adjustments for both high and low-speed compression damping as well as rebound control. Overall travel was set at 12.4 inches with 13 positions available for low-speed compression, 3.5 turns of high-speed control, and 17 available settings for rebound damping.

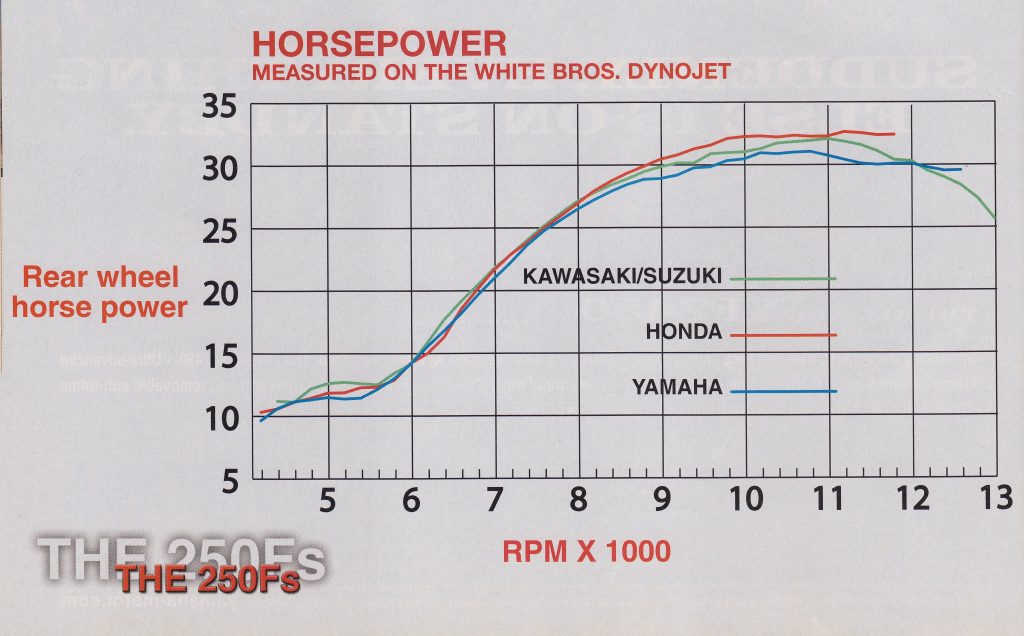

On White Brother’s dyno, the new CRF250R was a very impressive performer boasting the highest peak horsepower figures of the four contenders. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On White Brother’s dyno, the new CRF250R was a very impressive performer boasting the highest peak horsepower figures of the four contenders. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Riders of all sizes praised the new CRF for its slim, sleek, and comfortable feel. Photo Credit: Honda

Goldilocks: While its dyno numbers were impressive, its seat-of-the-pants feel was not quite as awe-inspiring. The CRF’s 249cc SOHC mill delivered a broad and easy-to-use powerband that hooked up well and pulled strongly through the midrange, but its power tapered off noticeably at the upper reaches of its rev range. Fast and aggressive riders preferred the longer pull of the Yamaha, but the CRF was a great do-it-all engine that split the difference between the torquey Kawasuki twins and the higher-revving YZ-F. Photo Credit: Le Big

Goldilocks: While its dyno numbers were impressive, its seat-of-the-pants feel was not quite as awe-inspiring. The CRF’s 249cc SOHC mill delivered a broad and easy-to-use powerband that hooked up well and pulled strongly through the midrange, but its power tapered off noticeably at the upper reaches of its rev range. Fast and aggressive riders preferred the longer pull of the Yamaha, but the CRF was a great do-it-all engine that split the difference between the torquey Kawasuki twins and the higher-revving YZ-F. Photo Credit: Le Big

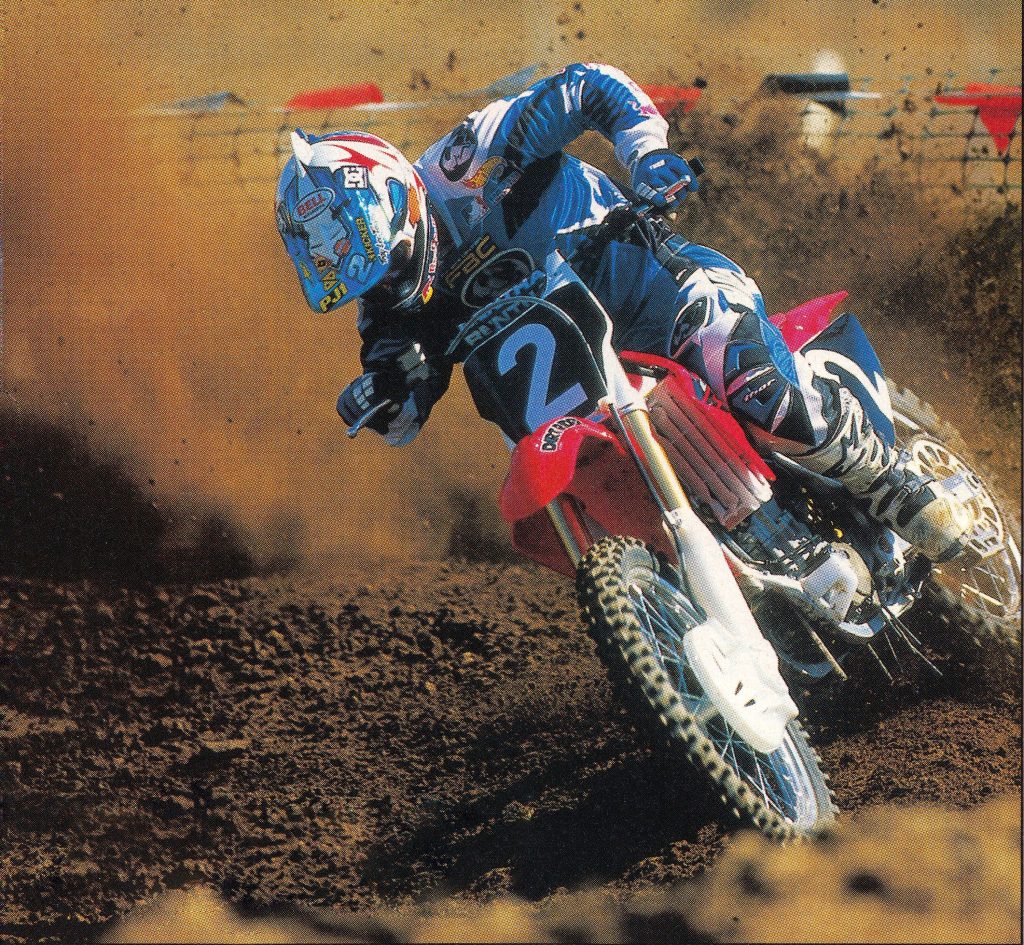

On the track, the CRF250R was competitive, but not quite the slam dunk the CRF450R had been two years before. The smaller Unicam motor delivered a wide and effective powerband that split the difference between the torquey Kawazuki twins and rev-happy Yamaha. The KX-F and RM-Z had most of their power focused on the lower portion of the rev range with chunky deliveries that were familiar to traditional four-stroke pilots. The twins revved slower and signed off sooner than the Honda and Yamaha, but all three motor designs were competitive if ridden correctly.

The addition of Honda’s CRF250R and Kawasaki/Suzuki’s fraternal twins finally brought competition to the 250F division in 2004. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The addition of Honda’s CRF250R and Kawasaki/Suzuki’s fraternal twins finally brought competition to the 250F division in 2004. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

At the opposite end of the powerband spectrum was Yamaha’s YZ250F. Its powerband was fairly soft down low, racy in the middle, and quasar on top. The YZ spooled up quickly, hit hard, and kept right on pulling until the cows came home and the valves started to float. It was the perfect powerband for experienced 125 pilots who liked to twist the throttle to the stops and leave it pinned out of every corner.

I picked up the first all-new 2004 CRF250R my local dealership received in the fall of 2003, trading in my 2002 CRF450R I had bought from them two years prior. I had also bought the all-new YZ250F in 2001 and loved everything about it except its absurd refusal to start at random intervals. The CRF450R had solved the starting frustrations, but I really missed the light and revvy feel of the 250F so I decided to give the sexy new Honda 250 a try. Unfortunately, this was one machine that I never did come to terms with. Unlike the YZ-F, this Honda always made me feel like I was in the wrong gear somehow. The powerband was stronger down low but less willing to rev out on top. I adored the looks, flawless build quality, and comfy ergos, but just never felt in sync with the smaller Unicam mill. I only kept this bike one year and traded it in on the all-new 2005 CRF450R a year later. Photo Credit: Me

I picked up the first all-new 2004 CRF250R my local dealership received in the fall of 2003, trading in my 2002 CRF450R I had bought from them two years prior. I had also bought the all-new YZ250F in 2001 and loved everything about it except its absurd refusal to start at random intervals. The CRF450R had solved the starting frustrations, but I really missed the light and revvy feel of the 250F so I decided to give the sexy new Honda 250 a try. Unfortunately, this was one machine that I never did come to terms with. Unlike the YZ-F, this Honda always made me feel like I was in the wrong gear somehow. The powerband was stronger down low but less willing to rev out on top. I adored the looks, flawless build quality, and comfy ergos, but just never felt in sync with the smaller Unicam mill. I only kept this bike one year and traded it in on the all-new 2005 CRF450R a year later. Photo Credit: Me

Compared to the blue, yellow, and green machines, the new Honda was a bit of a mix of both approaches. The CRF revved quicker than the twins, but not as aggressively as the YZ-F. It was less torquey than the green and yellow machines, but easier to get hooked up than the higher-strung Yamaha. The midrange power was comparable on all three, but once the revs started to climb the twins quickly threw in the towel. Both the CRF and Yamaha were far happier bouncing off the rev limiter but only the Yamaha kept pulling all the way to the outer limits.

Nathan Ramsey took the new CRF250R to several top-five finishes during the 2004 season including its first Supercross win at San Francisco. Photo Credit: Garth Milan

Nathan Ramsey took the new CRF250R to several top-five finishes during the 2004 season including its first Supercross win at San Francisco. Photo Credit: Garth Milan

The CRF’s biggest motor advantage was its flexibility. It offered a bit of the twin’s grunt and a smidge of the YZ-F’s rev. The CRF was slower on top than the Yamaha, but its powerband came on sooner and pulled over a broader range than the blue machine. It was torquier out of turns and chunky through the middle. The Honda was super easy to get hooked up and plenty fast enough for most riders below the pro class. Its clutch worked well, and the transmission was buttery smooth. Some riders had issues with the stock transmission ratios and fast guys preferred the more potent YZ-F motor, but most riders felt the Honda’s motor was competitive and impressive for a first-year design.

The CRF250R’s Showa damper was well-sorted and plush in action. For most riders below the pro class, the stock shock was an excellent performer. Photo Credit: Honda

On the chassis front, the new Honda was a very well-rounded machine. On the track, it felt noticeably lighter than the Yamaha despite both machines clocking in at the same 216 pounds. It was no 125 two-stroke, but riders praised its excellent ergonomics and tossable feel. The fourth-generation frame was slim, stout, and comfortable. The CRF was stable at speed, nimble in the air, and decent in the turns. Jumping the Honda was a dream, and the bike flew straight and never did anything unexpected. Like the CRF450R, some riders felt that the front end was less accurate than the Yamaha, while others seemed to love the turning of the CRF. The ones who had issues with the Honda complained of a touch of understeer at turn-in. The CRF250R was still a very good turner, but there was just not the flypaper-like stick to the front wheel that riders loved about the YZ-F. The Honda was sharper in the turns than the twins but just not quite as accurate and confidence-inspiring as the YZ-F if the track was tight and traction was at a premium.

2002 125 West Coast Supercross champ Travis Preston campaigned the new CRF250R for the Amsoil Factory Connection team in 2004. Preston’s season was solid, capturing several top-three finishes, but he was not able to duplicate the title-winning effort he had enjoyed in 2002. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

2002 125 West Coast Supercross champ Travis Preston campaigned the new CRF250R for the Amsoil Factory Connection team in 2004. Preston’s season was solid, capturing several top-three finishes, but he was not able to duplicate the title-winning effort he had enjoyed in 2002. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the suspension front, the CRF was very good overall. The Showa Twin-Chamber forks were well set up for most riders in the CRF’s target demo with spring rates that delivered a compliant feel without sacrificing big hit capability. They were plush overall, with just a hint of midstroke harshness in certain situations. Overall damping was excellent, and most riders could find an agreeable setup with the compression and rebound adjustments available. Serious aerial work was no problem and the CRF could be launched into the stratosphere without any concerns of excessive bottoming or wrist-busting spikes in the damping upon return to the terra firma.

With smooth power, excellent ergonomics, and a solid chassis the CRF250R was a nimble and confident flyer. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With smooth power, excellent ergonomics, and a solid chassis the CRF250R was a nimble and confident flyer. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the rear, the Showa damper was equally praised for its plush and well-sorted action. Fast guys complained a bit about the shock blowing through the stroke on serious G-outs and mega leaps, but most riders did not share this complaint. For them, dialing in a bit more high-speed compression seemed to get the damper settled and under control. It was plush on the small chop and suitably firm on big hits. Overall, the shock was smooth in action and comfy once dialed in. Some riders preferred the slightly firmer Yamaha damper but neither shock was a handicap on the track.

Honda motors are traditionally lauded for their reliability, but the first edition of the CRF250R powerplant suffered from a few concerning issues. Valve life was unimpressive and with its limited oil capacity and penchant for consumption, it was critical to keep a close eye on the motor’s dipstick. Even more concerning were reports of catastrophic engine failures caused by cracks in the lower cylinder skirt of several CRFs. Photo Credit: Honda

On the detailing front, the Honda was a mixture of excellent componentry and disappointing first-year bugaboos. On the plus side were the Honda’s plastic, seat, bars, grips, levers, and switchgear, which were of remarkable quality and easily the best in the class. The Honda used a better grade of bolts and a more uniform selection of sizes than the competition and that made the CRF easier to service. The alloy frame and bodywork looked great on the showroom floor and still looked great long after the blue, green, and yellow machines looked and felt beat. The motor was an easy and reliable starter, rarely hiccupped or flamed out, offered minimal compression braking, and never overheated. The stock muffler looked good and offered the least obnoxious exhaust note of the 250F contenders. The powerful Nissin brakes stopped on a dime, provided excellent feel, and rarely needed servicing. The clutch offered a light pull, stood up well to abuse, and rarely faded. The stock Renthal bars were sturdy, well-shaped, and one less thing a buyer had to immediately replace.

While the CRF250R was not the most aggressive handler in the class, its very capable chassis allowed riders to push the limits of traction, and their abilities, with confidence. Photo Credit: Honda

On the negative side of the equation, there were a few serious concerns that became apparent over time. Of these issues, by far the most troubling was a flaw in the CRF250R’s cylinder design that caused some motors to grenade when the lower skirt of the cylinder failed. This issue would be addressed on the CRF250R in 2005, but early adopters had to live with the possibility of a failure in 2004. The motor’s unique dual chamber oil system also made it imperative to keep a close eye on the little Honda’s thirsty oil consumption. There was not a lot of room for error with its meager capacity and it was critical to check the oil level before every ride. It was also important to make sure you put the two very different kinds of oils the CRF used in the right chambers. Top-end life was better than the on the Kawazuki twins, but far less robust than the nearly indestructible Yamaha. The YZ-F’s five-valve head required fewer services and less replacement of the internal components than the Honda’s less-robust Unicam setup.

Honda also unveiled an off-road version of the CRF in 2004. The all-new CRF250X offered much more performance than the XR250R it replaced in Honda’s lineup. Photo Credit: Honda

Honda also unveiled an off-road version of the CRF in 2004. The all-new CRF250X offered much more performance than the XR250R it replaced in Honda’s lineup. Photo Credit: Honda

The CRF’s stock air filter was of decent quality, but getting to it required tiny hands and a shoehorn to get it seated properly. The stock transmission shifted well and was reliable, but some riders felt the stock ratios were not perfectly in step with the CRF’s power output. There was a noticeable gap between 2nd and 3rd gear that left some riders flummoxed and in search of a different final drive ratio. Unfortunately, just swapping sprockets did not seem to fully address this problem as it adversely affected the CRF’s effectiveness at other points of the track. With time, most riders learned to carry second a bit longer or get a pipe and silencer to beef up the power and help the Honda pull the gap more effectively.

Honda’s all-new CRF250R took the 250F division by storm in 2004. Its impressive combination of easy-to-use power, great looks, solid suspension, and Honda cache were more than enough to make it a winner in the showrooms and on the track. Photo Credit: Honda

Overall, the 2004 CRF250R turned out to be a very competitive and incredibly popular machine. Much like the CRF450R two years before, the new red 250 was snapped up in droves by consumers. The CRF was not the fastest, sharpest turning, or most reliable bike in the class, but its combination of solid power, capable handling, and stellar looks was more than enough to turn it into a runaway sales success. Several magazines picked the CRF250R as the best all-around 250 four-stroke in 2004, but its wins were not unanimous. For riders making a living on their 250F, Yamaha’s faster and far more reliable YZ250F was probably a better choice in 2004. The CRF250R was a very capable first outing for Honda, but it still had a few bugs that needed to be worked out before it could truly unseat the reigning king of the deuce-and-a-half thumper division.