For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s mighty CR500R for 1991.

Bold new graphics, updated bodywork, and some strategic motor and suspension updates added up to a much-improved CR500R for 1991. Photo Credit: Honda

Bold new graphics, updated bodywork, and some strategic motor and suspension updates added up to a much-improved CR500R for 1991. Photo Credit: Honda

Once the preeminent machine in motocross, the Open class fell out of favor in the late 1980s. A shift towards Supercross and the ever-improving performance of the smaller bore machines bled consumer interest and development dollars away from the big bore behemoths that once ruled the tracks of America and Europe. By 1991, both Yamaha and Suzuki had abandoned the Open class, leaving Honda and Kawasaki as the lone Japanese competitors doing battle in the 500 motocross division.

In 1989, Honda dialed up the last major update for their venerable CR500Rs. The updated chassis was stiffer, and the attractive new bodywork was much slimmer. The only change that was not a tremendous hit was the new inverted forks which proved to be disappointing in their performance. Photo Credit: Me

In 1989, Honda dialed up the last major update for their venerable CR500Rs. The updated chassis was stiffer, and the attractive new bodywork was much slimmer. The only change that was not a tremendous hit was the new inverted forks which proved to be disappointing in their performance. Photo Credit: Me

In 1989, Honda gave their CR500R what would turn out to be its last major update with a complete redesign that revamped the chassis and significantly improved the notoriously pudgy machine’s ergonomics. The new “low boy” layout slimmed the tank, flattened the seat, lowered the center of gravity, and improved the looks of the mighty Honda five-oh-oh. The new frame was lighter and stronger, with a slightly less aggressive geometry and a 12mm lower subframe in the rear. The suspension was just as all-new, with a move to the ’88 CR250R’s “Delta Box” linkage in the rear and the introduction of Showa’s works-like 45mm inverted cartridge forks up front.

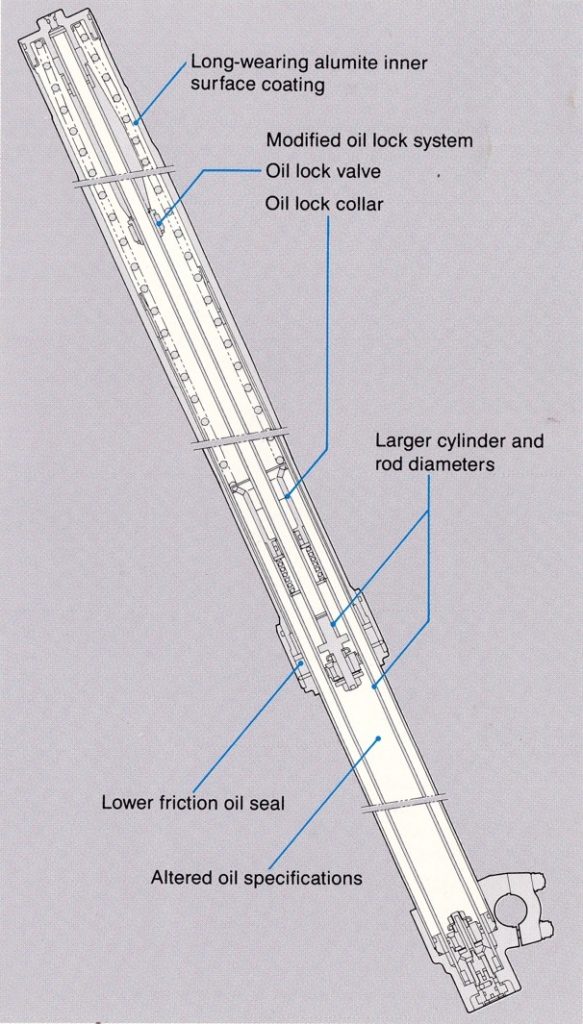

After two years of grim fork performance, Honda and Showa went back to the drawing board in 1991. The updated 45mm Showa units still lacked the adjustable rebound control of its rivals but a new enlarged cartridge system, redesigned bottoming system, and slick alumite coating looked to drag the CR’s forks out of last place in the 500 suspension sweepstakes. Photo Credit: Honda

After two years of grim fork performance, Honda and Showa went back to the drawing board in 1991. The updated 45mm Showa units still lacked the adjustable rebound control of its rivals but a new enlarged cartridge system, redesigned bottoming system, and slick alumite coating looked to drag the CR’s forks out of last place in the 500 suspension sweepstakes. Photo Credit: Honda

One area that was not all-new was the CR500R’s 491cc liquid-cooled powerhouse of a motor. Big, brawny, and bulletproof, this massive two-stroke single had been the brute of the Open class ever since its introduction in 1985. Despite lacking the KX500’s variable exhaust valve, the CR’s powerplant was blisteringly fast with an epically wide powerband and mountains of track rearranging torque. Some riders preferred the KX500’s smoother power delivery, but no one on this side of a loony bin or hill climb competition went looking for more power from the red machine’s fire-breathing mill.

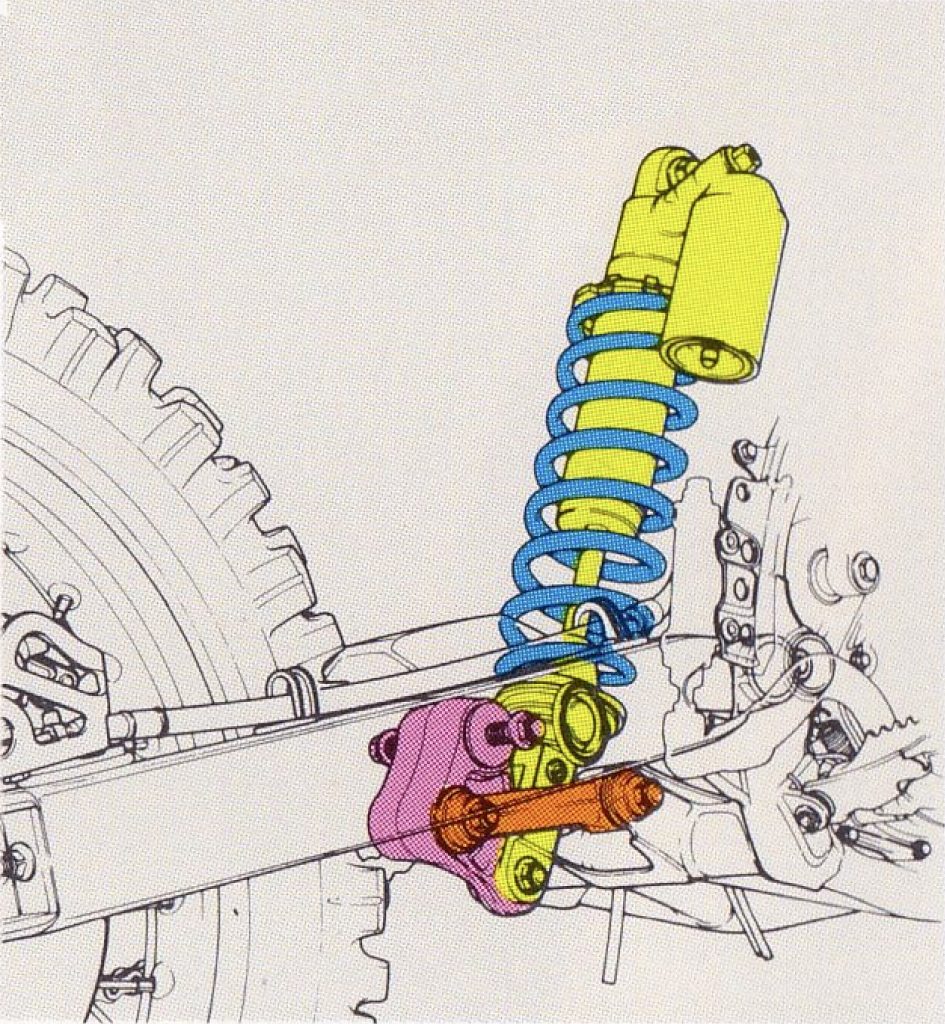

Big Switch: After a decade of using Showa dampers on their 500s, Honda made the move to Kayaba for the big CR’s shock provider in 1991. The new KYB shock was paired with a revamped Pro-Link linkage featuring a more progressive curve and new ultra-slick bushings that Honda claimed reduced friction in the rear end by 50%. Photo Credit: Honda

Big Switch: After a decade of using Showa dampers on their 500s, Honda made the move to Kayaba for the big CR’s shock provider in 1991. The new KYB shock was paired with a revamped Pro-Link linkage featuring a more progressive curve and new ultra-slick bushings that Honda claimed reduced friction in the rear end by 50%. Photo Credit: Honda

While 90% of the all-new CR500R proved to be an epic win, its new forks proved to be an even more epic failure. The 45mm Showa forks were undersprung, overdamped, and very harsh in action. The added weight and power of the 500 took a bit of a bite out of the midstroke spike that plagued the same forks on the CR250R, but no one was going to call the stock CR’s forks even remotely good. Aside from the grim forks, however, the all-new CR500R was a gem. It shredded turns, flew like an F-16, stopped on a dime, and dug massive trenches out of every turn. Without a power valve, the CR’s powerband was not as smooth and wide as the KX, but its turning and ergonomics were far superior to the green machine. For pro-level motocross racing it was an incredibly effective motocross package, but many less-skilled riders preferred the smoother power and far superior suspension of the 1989 KX500.

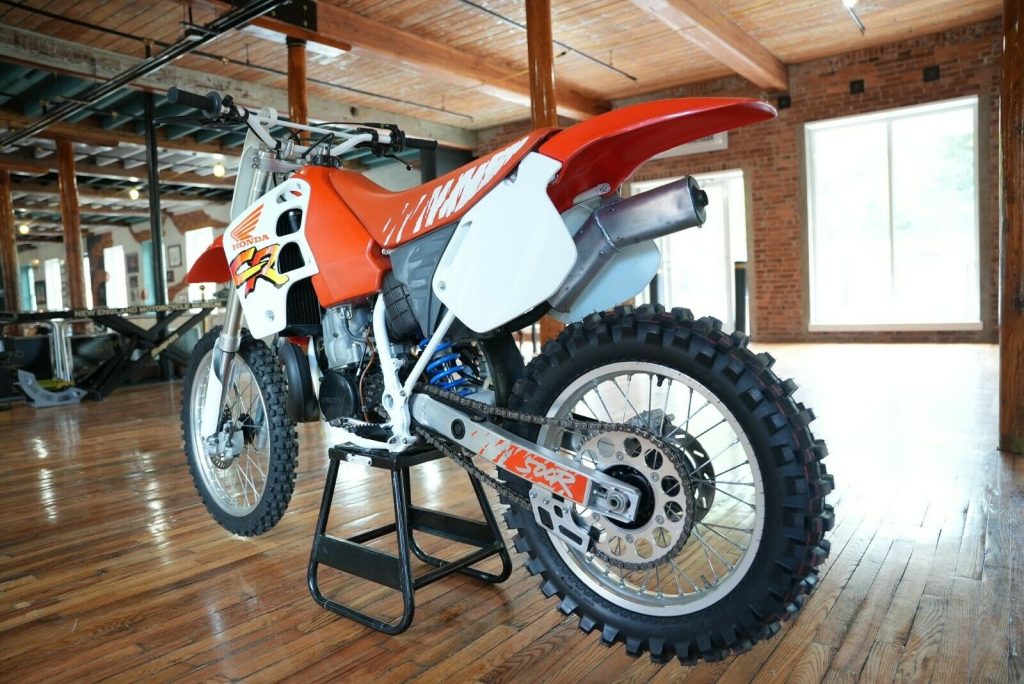

The 1991 season was the year for really Bold New Graphics in the moto world and conservative Honda did not prove immune to this aesthetic trend. The white shrouds, tiger stripes, and cartoony graphics were polarizing in their appeal and a serious departure from previously understated Honda designs. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

The 1991 season was the year for really Bold New Graphics in the moto world and conservative Honda did not prove immune to this aesthetic trend. The white shrouds, tiger stripes, and cartoony graphics were polarizing in their appeal and a serious departure from previously understated Honda designs. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

In 1990, Honda looked to broaden the power, improve stability, and refine the suspension package on their half-liter beast. A revamped frame altered the geometry slightly to reduce the Honda’s penchant for headshake and an all-new crank added more weight for a bit of additional chug. A new reed valve and reshaped head looked to further broaden the Honda’s arm-stretching delivery. Big changes in the forks included all-new internals that reduced friction by 30%, revised valving, and a redesigned oil-lock system designed to reduce bottoming and provide smoother action. Cosmetically, the CR500R’s bodywork was unchanged aside from a switch back to the “Flash Red” color of 1987 and a new coat of white paint for the frame.

Aside from its liquid cooling, the Honda’s big 491cc mill was not much different than what Roger De Coster was racing more than a decade before. This simplicity played into the CR500R’s incredible track record for reliability and made the machine’s infrequent top-end services much less complicated than those of its green competition. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

Aside from its liquid cooling, the Honda’s big 491cc mill was not much different than what Roger De Coster was racing more than a decade before. This simplicity played into the CR500R’s incredible track record for reliability and made the machine’s infrequent top-end services much less complicated than those of its green competition. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

Once again, the battle for 500-class dominance in 1990 came down to a battle between the Honda and Kawasaki. Yamaha’s YZ490 had its champions as a do-it-all machine, but most serious racers had written off its chances sometime during the Reagan administration. KTM’s 500 Motocross had tons of motor, but its poorly set-up suspension made even Honda riders avert their eyes. Big power and poor suspension were not a great racing combination, but the KTM could be competitive if you could find a knowledgeable tuner to sort out its Dutch White Power components.

Early on in his career Michigan’s Jeff Stanton was considered a 500 specialist. His rides on the outdated air-cooled YZ490 chasing Rick Johnson were legendary. Ironically, however, that big bike skill never translated to a 500 National title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Early on in his career Michigan’s Jeff Stanton was considered a 500 specialist. His rides on the outdated air-cooled YZ490 chasing Rick Johnson were legendary. Ironically, however, that big bike skill never translated to a 500 National title. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In the end, most riders once again picked the Kawasaki as the king of the 500 motocross division. Its new inverted KYB forks and updated Uni-Trak suspension were far superior to the lackluster Showa components found on the Honda and its powerband continued to be the broadest in the class. Motor changes for 1990 boosted the Honda’s low-end response and smoothed out its hit, but its lack of a power valve was noticeable when ridden back-to-back with the incredibly broad Kawasaki. The Honda’s turning and ergonomics were far superior to the bulky-feeling KX, but this was not enough to overcome the CR’s harsh suspension, predilection for headshake, and less-forgiving power.

One interesting choice Honda made in the early nineties was to stick with an 18” rear wheel long after the rest of the sport had moved on to 19” hoops. Since no sane person was likely to race a CR500R in a stadium, this was no serious disadvantage at the time. The 18” wheel gave the big CR excellent tire selection, a bit of extra cushion in the rough, and some additional insurance against flats. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

One interesting choice Honda made in the early nineties was to stick with an 18” rear wheel long after the rest of the sport had moved on to 19” hoops. Since no sane person was likely to race a CR500R in a stadium, this was no serious disadvantage at the time. The 18” wheel gave the big CR excellent tire selection, a bit of extra cushion in the rough, and some additional insurance against flats. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

After two seasons of losses in the shootouts and on the track at the hands of Jeff Ward, the CR500R was back with a significant list of updates for 1991. Visually, the most striking change was the all-new rear bodywork which was first introduced on the CR250R in 1990. The revamped rear section added a larger airbox, reshaped seat, restyled the side plates, and a sleeker rear fender design. The 500 did not get the 125 and 250’s new tank design, instead sticking with the larger 2.4-gallon unit introduced in 1989. New shrouds for 1991 kept the old shape but swapped the color from red to white and added a bold set of graphics to match the equally bold set of tiger stripes on the seat.

While thicker at the tank than its 125 and 250 siblings, the CR500R remained the slimmest and most comfortable machine in the class. Its seat was near perfection and its 2.4-gallon tank did a much better job of staying out of the rider’s way than the fuel cells on the KX500 and off-road-focused WR500.

While thicker at the tank than its 125 and 250 siblings, the CR500R remained the slimmest and most comfortable machine in the class. Its seat was near perfection and its 2.4-gallon tank did a much better job of staying out of the rider’s way than the fuel cells on the KX500 and off-road-focused WR500.

In addition to the new look, the CR featured an all-new suspension for 1991. Up front, the Showa forks were completely redesigned with a new “spring-above-cartridge” layout, which featured a larger cartridge unit, new valving, stiffer springs, and a revamped bottoming system. The fork tubes remained 45mm in diameter, but a new anodizing process was added to reduce friction and prevent the material contamination that had befouled the CR’s damping in the two previous seasons. As in the past, the fork offered external adjustments for compression, but no external way to adjust the rebound damping. Overall fork travel was set at 12 inches.

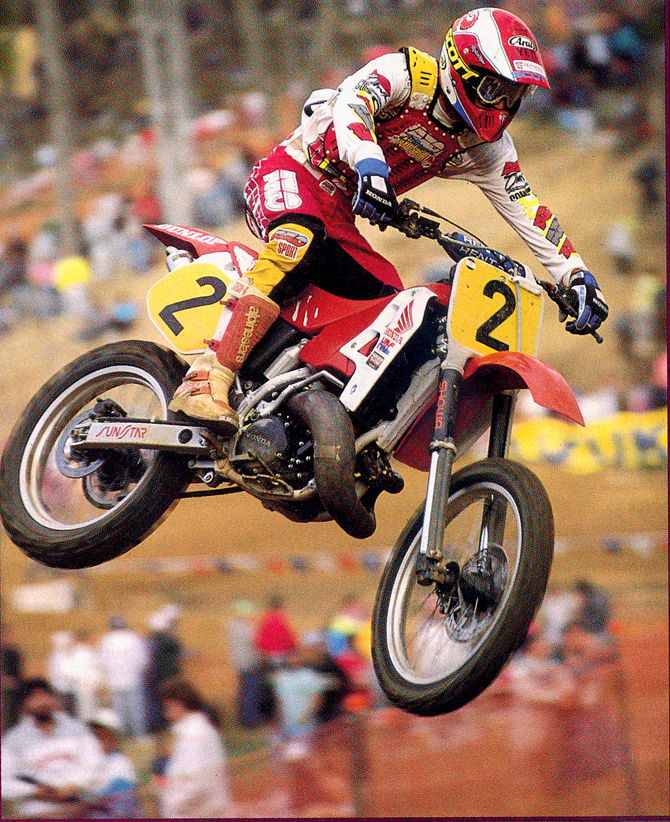

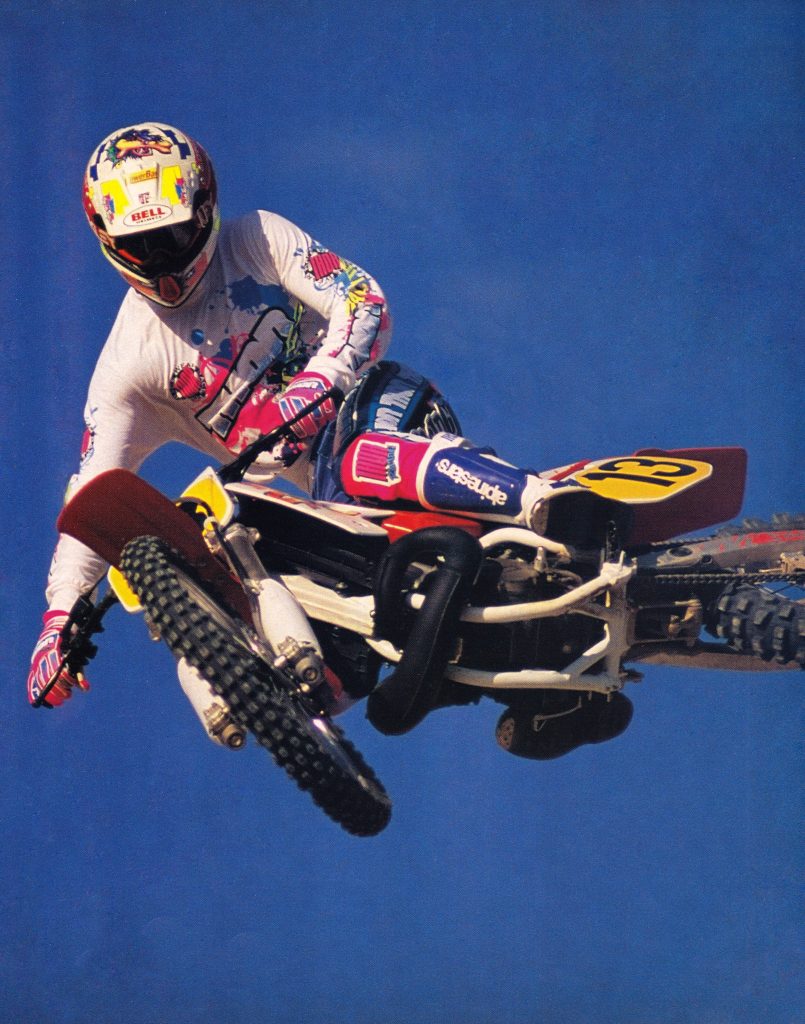

For a 60 horsepower 236-pound machine the 1991 CR500R was an absolute shredder. Tight turns and off-cambers that gave the Honda’s competition fits were carved up with ease on the big red five-honey. Headshake at speed remained a constant companion, but if the track was tight the CR had no peer. Photo Credit: Chris Hultner

For a 60 horsepower 236-pound machine the 1991 CR500R was an absolute shredder. Tight turns and off-cambers that gave the Honda’s competition fits were carved up with ease on the big red five-honey. Headshake at speed remained a constant companion, but if the track was tight the CR had no peer. Photo Credit: Chris Hultner

In the rear, Honda chose to ditch Showa completely and go with a Kayaba damper for 1991. The new shock offered 12.6 inches of travel with 22 adjustable compression settings and 20 selectable settings for rebound control. The new shock was paired with a revamped linkage which offered a more progressive ratio and new Teflon bushings that Honda claimed reduced friction by 50%.

Open-class bikes are about big power and the CR500R had that base covered in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Open-class bikes are about big power and the CR500R had that base covered in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Frame updates for 1991 included an all-new subframe to accommodate the revamped rear bodywork and an update to the geometry designed to further quicken the Honda’s already excellent turning. The rake was pulled in from 28.3 to 27.8 degrees and the trail was reduced from 4.7 to 4.5 inches. The CR’s wheelbase was also reduced by .02 inches moving from 59.1 to 58.9 inches.

Subtle changes to the combustion chamber, intake, and carburetor yielded impressive results for the CR500R in 1991. The revamped powerband was easier to control off the bottom and smoother through the middle. This more friendly power delivery made it less tiring to ride and more effective at finding traction if the track was slick. Really fast guys missed some of the old motor’s hit, but most riders felt the new smoother powerband was a significant improvement. Photo Credit: Honda

Subtle changes to the combustion chamber, intake, and carburetor yielded impressive results for the CR500R in 1991. The revamped powerband was easier to control off the bottom and smoother through the middle. This more friendly power delivery made it less tiring to ride and more effective at finding traction if the track was slick. Really fast guys missed some of the old motor’s hit, but most riders felt the new smoother powerband was a significant improvement. Photo Credit: Honda

On the motor front, the 1991 CR500R continued to feature the same basic design it had employed since the move to liquid cooling in 1985. The 491cc mill eschewed any sort of variable exhaust valve trickery with liquid cooling and a digital ignition being its only nods to modern two-stroke design. For 1991, Honda reshaped the combustion chamber and shaved 0.1mm off the carburetor slide to improve low-end response. Aside from these small updates, the big single was unchanged from the year before.

In 1989, many pit pundits had Honda’s new 250 Supercross and Motocross champ Jeff Stanton pegged for his first 500 National Motocross title. Instead, it was Kawasaki’s long-time veteran Jeff Ward who took home his first 500 championship on his KX500. After a successful title defense in 1990, Ward was back with an attempt to make it three in a row in 1991. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

In 1989, many pit pundits had Honda’s new 250 Supercross and Motocross champ Jeff Stanton pegged for his first 500 National Motocross title. Instead, it was Kawasaki’s long-time veteran Jeff Ward who took home his first 500 championship on his KX500. After a successful title defense in 1990, Ward was back with an attempt to make it three in a row in 1991. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

On the track, the 1991 Honda CR500R turned out to be a much-improved machine. The subtle motor changes yielded surprisingly dramatic results with the revamped mill delivering a much smoother power delivery than in the past. Low-end response was less abrupt, and the motor no longer exploded in the midrange. The CR was still incredibly fast, but its powerband was smoother, torquier, and more electric. For most riders below the pro class, the mellower delivery was an improvement. The updated power plant was easier to manage on slick surfaces and less tiring to ride. There was not a ton of pull past the midrange, but most non-pros did not lament the relative lack of revs. In most cases, it was far saner and more effective to keep it a gear high and short shift the big Honda rather than hold it wide open like a 125. This prevented the big motor from binding up the chassis and allowed the CR to stay hooked up and in the meat of its power.

In 1991, France’s Jean-Michel Bayle moved up from the 125 class and proceeded to dominate the big bike standings. His ultra-smooth style was a perfect match to the power of 500s as he raced to victory in three of the six 500 series rounds. His victory in the 1991 500 National Motocross series would cap the first three title sweep in the sport’s history. Photo Credit: Racer X

In 1991, France’s Jean-Michel Bayle moved up from the 125 class and proceeded to dominate the big bike standings. His ultra-smooth style was a perfect match to the power of 500s as he raced to victory in three of the six 500 series rounds. His victory in the 1991 500 National Motocross series would cap the first three title sweep in the sport’s history. Photo Credit: Racer X

Keeping the CR in the right gear was easy with its bulletproof clutch and excellent transmission. Both worked flawlessly aside from a slightly hefty pull at the lever. Keeping the cable well-lubed helped but the Honda’s clutch pull was fairly heavy compared to most Japanese machines of the time. The tradeoff for this hefty pull was a remarkable ability to take abuse and the CR’s clutch was positive in its engagement and more than up to the antics of most hammerheads. The transmission was equally dependable with well-matched gears, a slick feel, and a positive engagement. Most tracks could be ridden in two gears and the Honda never missed a shift or left you wanting for more ratios.

The updates to Showa’s 45mm inverted forks delivered improved results for 1991. They were far from plush, but they did a decent job of dealing with most track obstacles. The added power and weight of the 500 seemed to reduce much of the harshness of the same forks delivered on the CR250R. Photo Credit: Honda

The updates to Showa’s 45mm inverted forks delivered improved results for 1991. They were far from plush, but they did a decent job of dealing with most track obstacles. The added power and weight of the 500 seemed to reduce much of the harshness of the same forks delivered on the CR250R. Photo Credit: Honda

In an outright drag race, the KIPS-equipped KX500 still had a slight advantage over the Honda in 1991. The Kawasaki offered more top-end power and a slightly wider powerband, but the new CR mill closed the gap significantly in rideability on the track. The wider powerband and smoother delivery produced what many considered to be the best Open class Honda powerband since the glory days of the CR480R. Really fast guys missed the old bruiser’s tire-shredding hit, but for riders not named Stanton or Bayle, it was a fantastic Open-class power plant.

The Gold Standard: On a bike as fast as a 500, great brakes were vital, and in 1991, no brakes in motocross were as powerful, reliable, and easy to modulate as Honda’s excellent Nissin components.

The Gold Standard: On a bike as fast as a 500, great brakes were vital, and in 1991, no brakes in motocross were as powerful, reliable, and easy to modulate as Honda’s excellent Nissin components.

On the Suspension front, the CR500R was once again improved in 1991. In 1990, the 500 delivered by far the best suspension performance of all the full-sized CRs. It was still not very good, but the big power and hefty weight of the five-honey seemed to be a better fit with the stock Showa components. In 1991, this was once again the case with the new Showa/Kayaba combo delivering Honda’s best suspension performance since 1988. The revamped Showa forks were far less harsh feeling than the same units found on the 250 and most riders could race them without the need for a revalve. The stock spring rates were right in the ballpark for most 500 racers and the stock valving did a good job of taking the bite out of most track obstacles. No one was going to call them plush, and the lack of adjustable rebound damping handicapped them slightly vs the more versatile KYB units found on the Kawasaki, but for hardcore motocross racing they worked well.

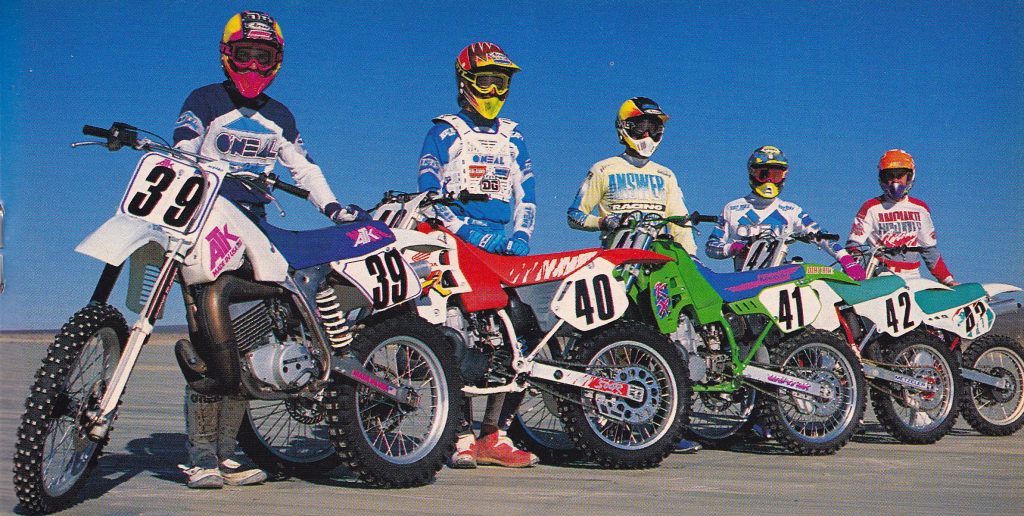

In 1991, the Open Class offered quite a diverse assortment of machines looking to satisfy a rider’s penchant for big power. Traditional 500 torque monsters like Honda’s CR500R, KTM’s 500MX, and Kawasaki’s KX500 did battle with middleweights like the ATK 406 and KTM’s tweener 300MX. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1991, the Open Class offered quite a diverse assortment of machines looking to satisfy a rider’s penchant for big power. Traditional 500 torque monsters like Honda’s CR500R, KTM’s 500MX, and Kawasaki’s KX500 did battle with middleweights like the ATK 406 and KTM’s tweener 300MX. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In the rear, the new KYB damper was once again an improvement but the upgrade from 1990 was not as dramatic. There was still a bit of choppiness in the rough and the shock was not super plush, but it did a decent job of smoothing out the track in most situations. Big hits were taken well, and the shock could be charged into whoops without fear of the CR kicking or doing anything crazy. For play riding and the occasional off-road excursion, the plusher Kawasaki damper was superior, but for motocross racing their performance was comparable.

The new KYB damper for 1991 performed well overall but it lacked the plushness of the Kawasaki’s rear end. Photo Credit: Honda

The new KYB damper for 1991 performed well overall but it lacked the plushness of the Kawasaki’s rear end. Photo Credit: Honda

On the handling front, the CR continued to be the most aggressive machine in the class. Compared to the big and stable KX and KTM, the Honda felt like a 125 in the turns. It loved the inside line and had little trouble carving in, under, and around its big-bore competition. Turning was effortless and the Honda could be trusted to stick like glue in slick turns and on tricky off-cambers that required concentration and careful body placement on the competition. Jumping was also excellent, and the CR was about as nimble as a heavy and overpowered machine could be expected to be. With the heavy vibes and serious gyro effect of that big piston, the CR was no freestyler, but the Honda could be whipped and aired out without concern for it doing anything scary or unexpected.

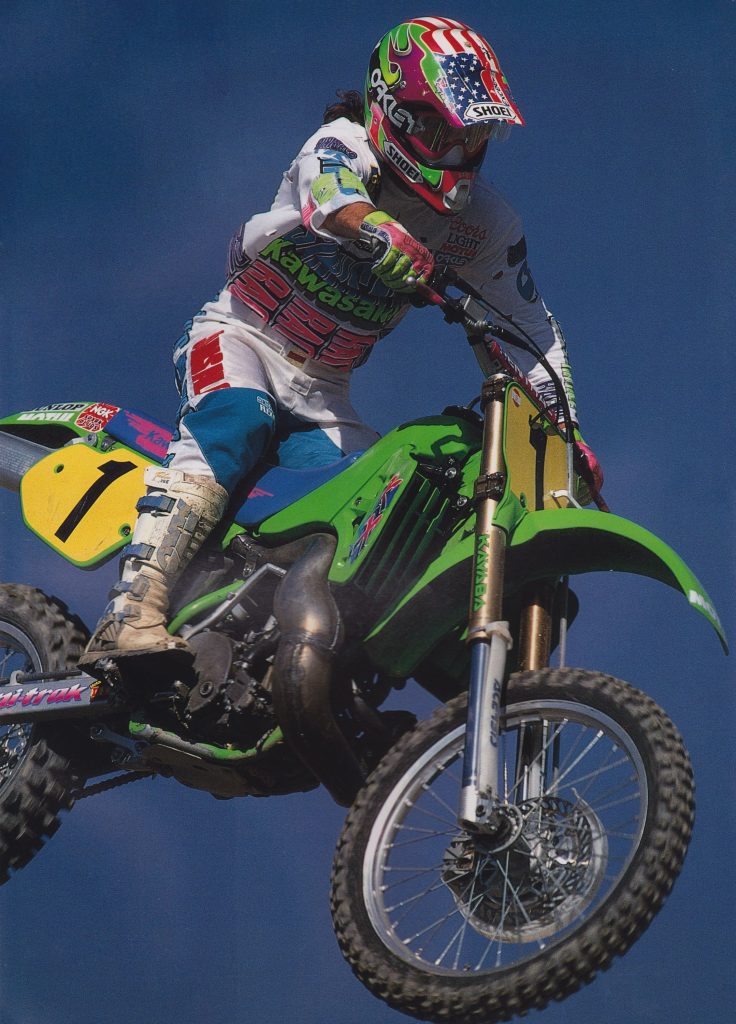

Talented riders like Honda’s Ricky Johnson could get pretty stylish on the CR500R. With its big power, large size, and hefty weight the red machine was never going to be mistaken for a 125, but if you had the skill to handle its potent delivery it was an excellent jumper. Photo Credit: Thor

Talented riders like Honda’s Ricky Johnson could get pretty stylish on the CR500R. With its big power, large size, and hefty weight the red machine was never going to be mistaken for a 125, but if you had the skill to handle its potent delivery it was an excellent jumper. Photo Credit: Thor

Once the speeds ramped up, however, the Honda was at a significant disadvantage to its rivals. The red machine’s excellent low-speed handling did not translate well to fast and rough tracks where the KTM and Kawasaki were far more at home. The Honda’s infamous headshake remained, and it could be pretty terrifying once that front end started dancing. Depending on the track, this was not always a problem, but if you were looking for a do-it-all machine to take off-road or out to the desert the Honda was not the best choice.

The stock bars, grips, levers, and controls on the CR500R were the class of the field in 1991. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

The stock bars, grips, levers, and controls on the CR500R were the class of the field in 1991. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

On the detailing front, the Honda was the class of the field in 1991. The lack of a power valve hurt it a bit in the power category, but it made the CR much less hassle to rebuild. Only the motors on ATK’s air-cooled 406 and Yamaha’s reimagined WR500 were simpler to take apart and put back together. The stock motor was incredibly durable and for most riders, it was a check it once a year affair. It was an easy starter (for a 500) hot or cold, was jetted well, and never fouled a plug. As long as you did not poke a hole in the radiator, it was as bulletproof as any motor could hope to be. The transmission and clutch worked flawlessly and held up to abuse well. Even when ridden hard, the clutch never faded, and the engagement remained consistent. Honda’s insistence on sticking with an 18-inch rear wheel was a bit controversial, but it provided some extra insurance against flats if you planned on venturing off the track. The CR’s brakes were super strong, never needed bleeding, and worked flawlessly. The selection and quality of bolts were by far the best in the class with more uniform sizes and a greater use of welded-on nuts. The quality, durability, and comfort of the bars, levers, grips, and seat foam all showed Honda’s commitment to producing the best-built machines in motocross.

Jeff Stanton may have missed out on the 1991 500 National Motocross title, but he played the hero role in Valkenswaard leading America to its eleventh straight Motocross des Nations title on his CR500R. Photo Credit: Unknown

Jeff Stanton may have missed out on the 1991 500 National Motocross title, but he played the hero role in Valkenswaard leading America to its eleventh straight Motocross des Nations title on his CR500R. Photo Credit: Unknown

While the overall build quality of the CR500R was excellent, it still had a few areas in need of improvement in 1991. In 1990, Honda recessed the stock graphics into the shrouds, which made them incredibly durable. In a cost-cutting measure, Honda went back to a standard decal for 1991 and they proved far less resistant to abuse. The new seat graphics also tended to wear off over time because of their placement where the rider gripped the machine most often. Of course, many riders did not care for the look of big orange CR graphics and tiger stripes in the first place so perhaps this was a feature, not a bug. The new airbox was roomier and easier to service, but the stock filter was not particularly durable. Investing in an aftermarket Twin Air or Uni filter was a good idea to keep your $4098 purchase running at its best. The stock rims were of decent quality, but cracked hoops were not unheard of on hard-ridden machines. Keeping a close eye on the spokes and regularly checking for cracks was a good idea to prevent a potentially painful failure. While you were checking the wheels, it was also a good idea to pack some grease into the linkage and steering head, as both came pretty dry from the factory.

In 1991, Honda offered a very competitive 500 package. It’s motor and suspension lacked some of the finesse of the class-leading Kawasaki, but the Honda countered with sharper handling, better brakes, slimmer ergos, and superior build quality. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

In 1991, Honda offered a very competitive 500 package. It’s motor and suspension lacked some of the finesse of the class-leading Kawasaki, but the Honda countered with sharper handling, better brakes, slimmer ergos, and superior build quality. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Overall, the 1991 Honda CR500R turned out to be an excellent Open class racer. Its updated motor was the tractor of the 500 division and riders loved its luscious vibes and smooth delivery. The Showa forks and Kayaba shock were not awe-inspiring, but they performed well enough to win races without sending them out for aftermarket upgrades. The CR’s turning, brakes, and overall quality were second to none. It was wicked fast, razor-sharp, and impeccably finished. If you were looking for a bit less moto in your Open class cocktail, then Kawasaki’s KX500 or Yamaha’s WR500 may have been a better choice, but for serious track work, it was hard to go wrong riding red in 1991.