For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new 1982 CR125R.

Handsome, fun, and competitive, Honda’s CR125R was much improved for 1982. Photo Credit: Honda

Handsome, fun, and competitive, Honda’s CR125R was much improved for 1982. Photo Credit: Honda

The early 1980s were a time of massive innovation in the motocross world. The long travel dual shocks of the 1970s were transitioning to the single shocks and complex suspension linkages of the 1980s. Water cooling, stout forks, and much-improved brakes were allowing riders to achieve speeds on the track that would have been unheard of a decade before.

In 1981, Honda swung for the fences with their radically new CR125R but grounded out to first base in the minds of most racers. Overweight, underpowered, and beset with a litany of reliability issues, the last of the Elsinores proved a colossal disappointment. Photo Credit: LeBig

In 1981, Honda swung for the fences with their radically new CR125R but grounded out to first base in the minds of most racers. Overweight, underpowered, and beset with a litany of reliability issues, the last of the Elsinores proved a colossal disappointment. Photo Credit: LeBig

While these innovations increased performance, they were not without their share of growing pains. Some early water-cooling setups affected handling, and they were often unreliable. Cold seizures, overheating, and leaking lines were common problems besetting these early innovators. Beefy forks and ever more capable shocks encouraged riders to push their machines to the point of overtaxing the metallurgy found in their frames and suspension components. As riders pushed the envelope of speed on these new machines, the engineers were often left playing catchup to keep their radical designs from failing under the pressure.

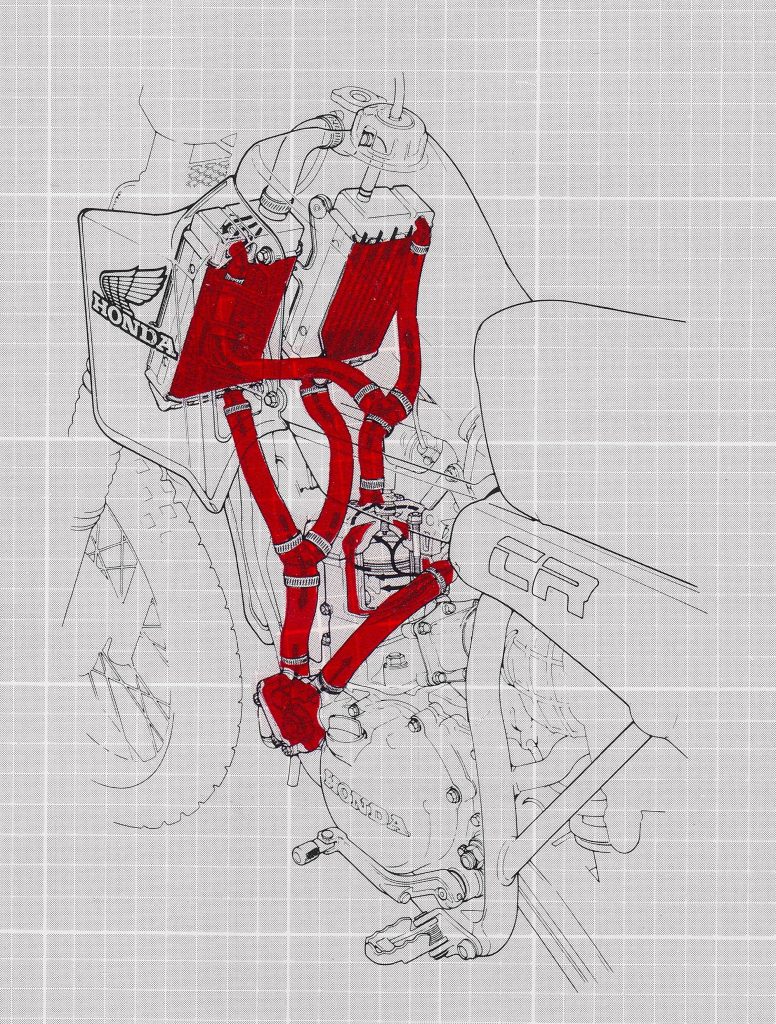

A redesigned “Dual Flow” cooling system for 1982 lowered the radiators on the chassis, improved the water pump’s efficiency, and reduced operating temperatures by circulating hot coolant through both radiators simultaneously. Photo Credit: Honda

A redesigned “Dual Flow” cooling system for 1982 lowered the radiators on the chassis, improved the water pump’s efficiency, and reduced operating temperatures by circulating hot coolant through both radiators simultaneously. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1981, this was exactly the scenario that played out in the Honda camp. The all-new CR125R Elsinore was easily one of the most radically redesigned machines in the 125 class. This season, Honda changed literally everything on their one-two-five, introducing their version of a single shock rear suspension and moving to water-cooling for their 122cc mill. The new Elsinore was bold in appearance, with its bright red motor and Buck Rogers bodywork. On paper, it seemed works bike trick, but on the track, it failed to hit the mark for most aspiring 125 pilots.

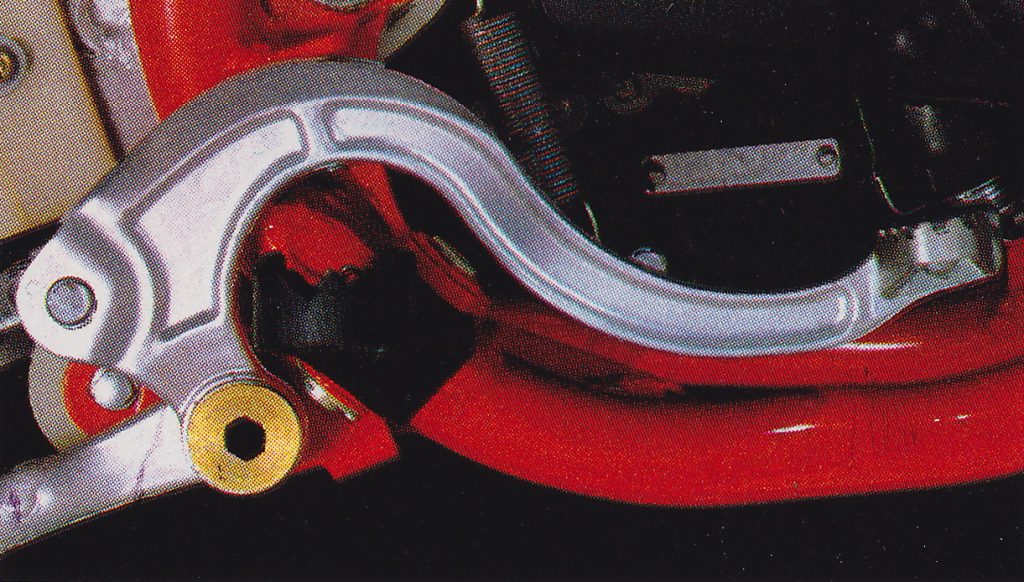

A redesigned Pro-Link rear suspension system for 1982 featured a stronger box-section swingarm, revamped linkage, and all-new compression-adjustable Showa damper. Photo Credit: Honda

A redesigned Pro-Link rear suspension system for 1982 featured a stronger box-section swingarm, revamped linkage, and all-new compression-adjustable Showa damper. Photo Credit: Honda

This season, Suzuki’s equally radical new RM125-X stole most of the Honda’s thunder with a stronger motor and far superior suspension. The Suzuki’s Full-Floater rear suspension wowed riders with its ability to smooth out the track while the Honda’s trick new Pro-Link suffered from fading shocks, cracked swingarms, and a penchant for blowing the hose off its remote reservoir. The red machine’s liquid-cooled motor was equally disappointing with tons of top-end but very little else. Its clutch dragged and lurched and its new water-cooling system overheated. At 218 pounds it was the porker of the 125 class and even with the added heft, its frame proved fragile and prone to failure. As a showcase for new technology, the 1981 CR125R Elsinore was a hit, but by most other metrics, the spacy Honda proved a serious disappointment.

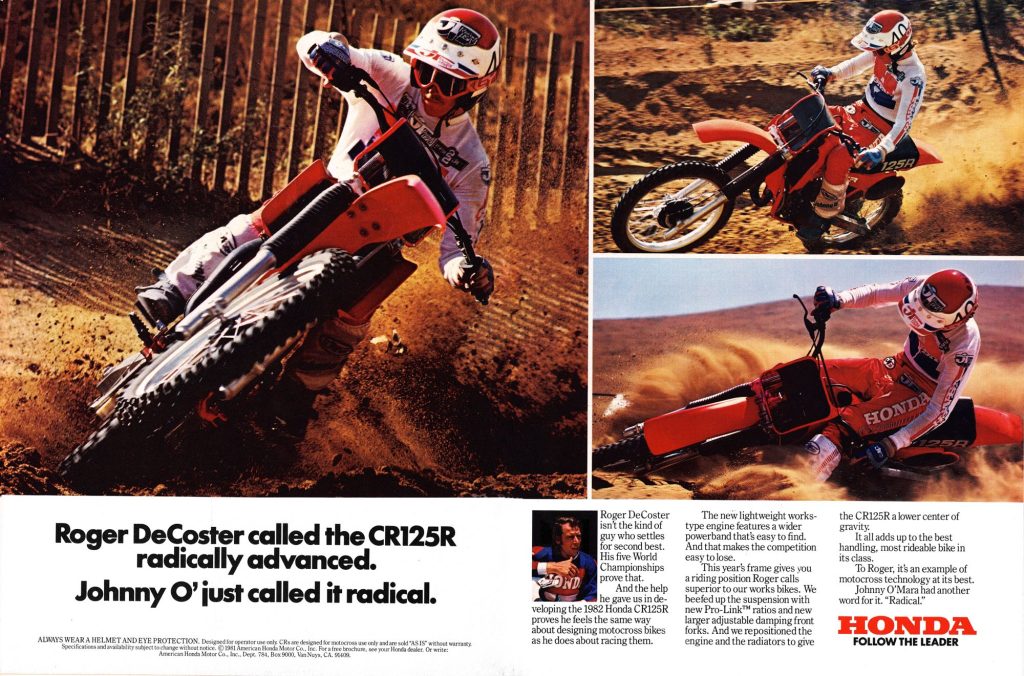

After a seriously disappointing showing in 1981, the entire Honda motocross lineup was redesigned and much improved for 1982. Photo Credit: Honda

After having Suzuki ate their lunch in 1981, Honda was determined to provide a better showing in 1982. This model year was the first to enjoy the full benefits of Roger De Coster’s input after he retired from full-time racing in 1980. The De Coster-supervised CRs looked to address the reliability and performance concerns that plagued the ’81 machines by trimming weight, increasing strength, boosting power, and improving durability. Literally every component was put under the engineering microscope for 1982 to improve performance.

An all-new frame for 1982 offered a stronger construction and much more aggressive geometry to improve the red 125’s turning manners. Photo Credit: Moto Journal

An all-new frame for 1982 offered a stronger construction and much more aggressive geometry to improve the red 125’s turning manners. Photo Credit: Moto Journal

First up on the chopping block for 1982 was the CR’s longtime moniker “Elsinore”. Originally introduced on the 1973 CR250M, the Elsinore name was a tip of the cap to Southern California’s Elsinore GP. A major event at the time, the Elsinore GP’s prominence in the sport had faded greatly in the decade since the first CR’s introduction. In 1982, Honda’s motocross lineup dropped the “Elsinore” from their name and signaled the beginning of a new era for the red machines.

Early 1980s 125 racing was dominated by Suzuki and their revolutionary Full Floater RM125. Some other bikes were faster, but no other 125 put all the pieces together like the screaming yellow Zonker. Photo Credit: Cycle World

Early 1980s 125 racing was dominated by Suzuki and their revolutionary Full Floater RM125. Some other bikes were faster, but no other 125 put all the pieces together like the screaming yellow Zonker. Photo Credit: Cycle World

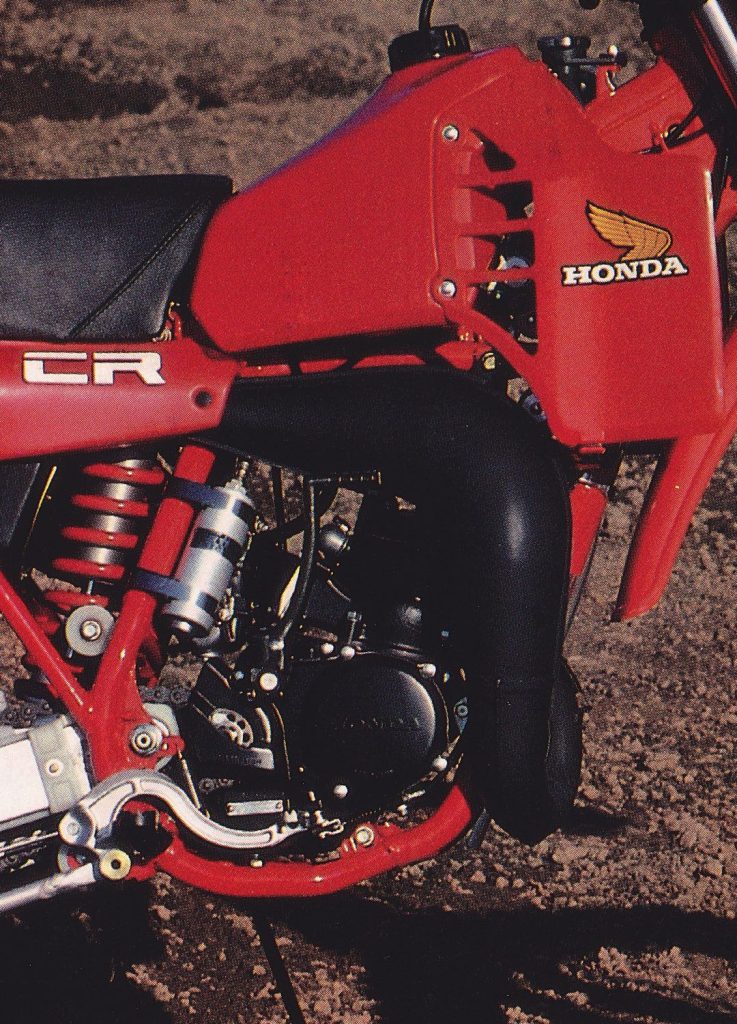

In addition to the new name, the 1982 CR125R received serious upgrades in nearly every facet of its design. In 1981, one issue that had plagued the 125 Honda was overheating. The new water-cooling system pumped all the hot coolant coming out of the motor into the right radiator, then circulated that coolant into the left, before returning it to the water pump. In practice, this proved inefficient at removing heat from the high-strung 122cc mill.

In 1982, Honda rethought the entire cooling system for their 125. First up was an all-new water pump tucked that in 6mm tighter and offered a slowed impeller speed to allow coolant to flow more efficiently. Secondly, they added a splitter to the hose coming out of the head and all-new radiators that allowed the coolant to circulate through both radiators simultaneously. To prevent the loss of coolant in long motos, the radiator cap was also upgraded in 1982 to resist three more pounds of pressure before venting coolant. These new “Dual Flow” radiators were then relocated to sit 60mm lower on the chassis for improved ergonomics and better mass centralization.

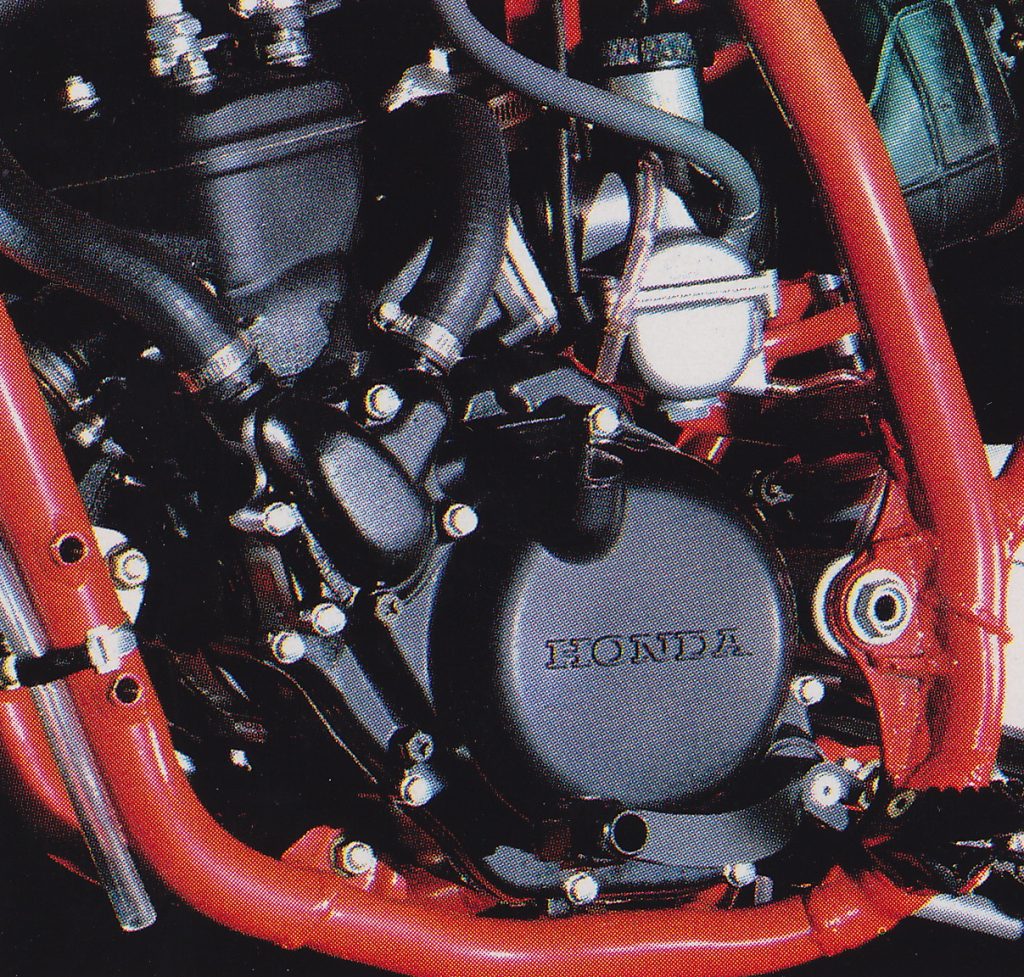

All-new in 1981, the CR’s 122cc motor featured a list of significant refinements for 1982. Improved cooling, all-new porting, more responsive reeds, a revamped ignition, and an all-new exhaust aimed to boost low-to-midrange power and improve the peaky ’81 motor’s usability. Photo Credit: Honda

All-new in 1981, the CR’s 122cc motor featured a list of significant refinements for 1982. Improved cooling, all-new porting, more responsive reeds, a revamped ignition, and an all-new exhaust aimed to boost low-to-midrange power and improve the peaky ’81 motor’s usability. Photo Credit: Honda

In addition to the improved cooling, the new CR125R motor had all-new porting that aimed to beef up its high-strung 1981 powerband. The cylinder offered a steel liner, an improvement in the eyes of many over the unborable chrome liners found on many CRs of the past. This was a bit of extra insurance with many early liquid-cooled machines suffering from “cold seizures” as riders unaccustomed to the new “warm up” procedure hit the track before letting their water pumpers get up to temp. If you did lock up your new CR, its liner could be bored, rather than having to pop for an all-new jug. Eventually, the engineers would figure out the right combinations of alloys for the cylinder, piston, and rings to eliminate this problem, but in 1982, liquid cooling was still at the bleeding edge of motocross design.

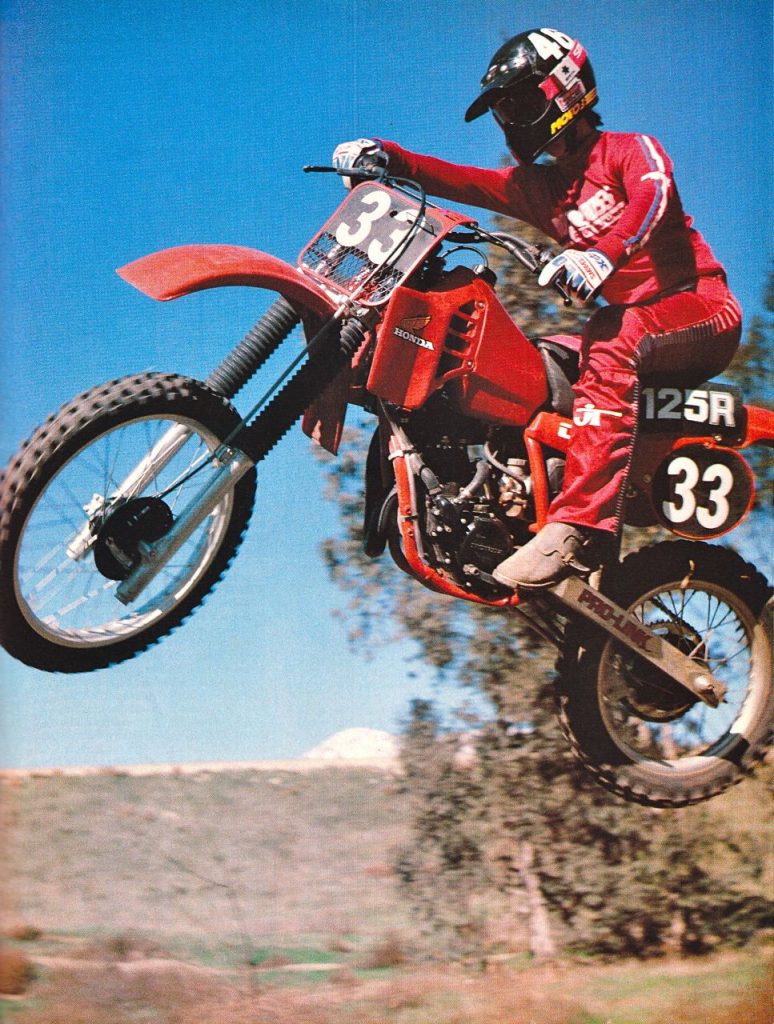

The ’82 CR125R was no lightweight, but its nimble chassis, comfortable ergonomics, and snappy power made it a fun bike to jump and ride. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The ’82 CR125R was no lightweight, but its nimble chassis, comfortable ergonomics, and snappy power made it a fun bike to jump and ride. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The new porting specs for 1982 raised the intake port 0.5mm and paired that with a similarly shorter piston. Bore and stroke remained unchanged at 55.5mm x 50.7mm for an overall displacement of 122cc. The CR125R retained the 34mm round-slide Keihin carb used in 1981 but added all-new reeds that moved to fiber for their construction from the steel employed in 1981. The ignition for 1982 was modified to provide a bit less advance and a new expansion chamber offered a revised shape for improved ground clearance and beefed up low-to-mid power. Unlike Yamaha’s new YZ125, the Honda’s motor lacked any sort of variable exhaust valve to broaden its power. In 1982, only the YZ125 offered this important advancement, and it gave the yellow machine a significant power advantage over its rivals. A new clutch for 1982 added one additional plate to improve the durability and feel of the poorly received 1981 basket.

After retiring from full-time racing at the end of the 1980 season, 5-time World Motocross champion Roger De Coster moved in-house to help develop Honda’s production motocrossers. The much-improved 1982 CRs were the first to benefit from The Man’s wisdom and expertise. Photo Credit: Honda

After retiring from full-time racing at the end of the 1980 season, 5-time World Motocross champion Roger De Coster moved in-house to help develop Honda’s production motocrossers. The much-improved 1982 CRs were the first to benefit from The Man’s wisdom and expertise. Photo Credit: Honda

On the chassis front, the CR’s frame was all-new for 1982. The new frame featured a stronger chromoly steel construction, a significant change in geometry, and a half-inch extension to the CR’s wheelbase. The ’82 chassis increased rake by three degrees and reduced trail by nearly an inch. The revamped frame relocated the mountings for the Pro-Link rear suspension and repositioned the pegs to be 10mm higher and 70mm forward. The updated linkage featured a new progression curve and was paired with an all-new Showa damper. The redesigned shock deleted the four-way rebound control offered in 1981 in favor of four external adjustments for compression damping. The new shock retained an external reservoir to fight fading and featured a slightly longer stroke for 1982 at 12.2 inches of overall travel. A revamped swingarm moved to a “box-section“ design for increased strength and added “insert type” chain adjusters for improved reliability.

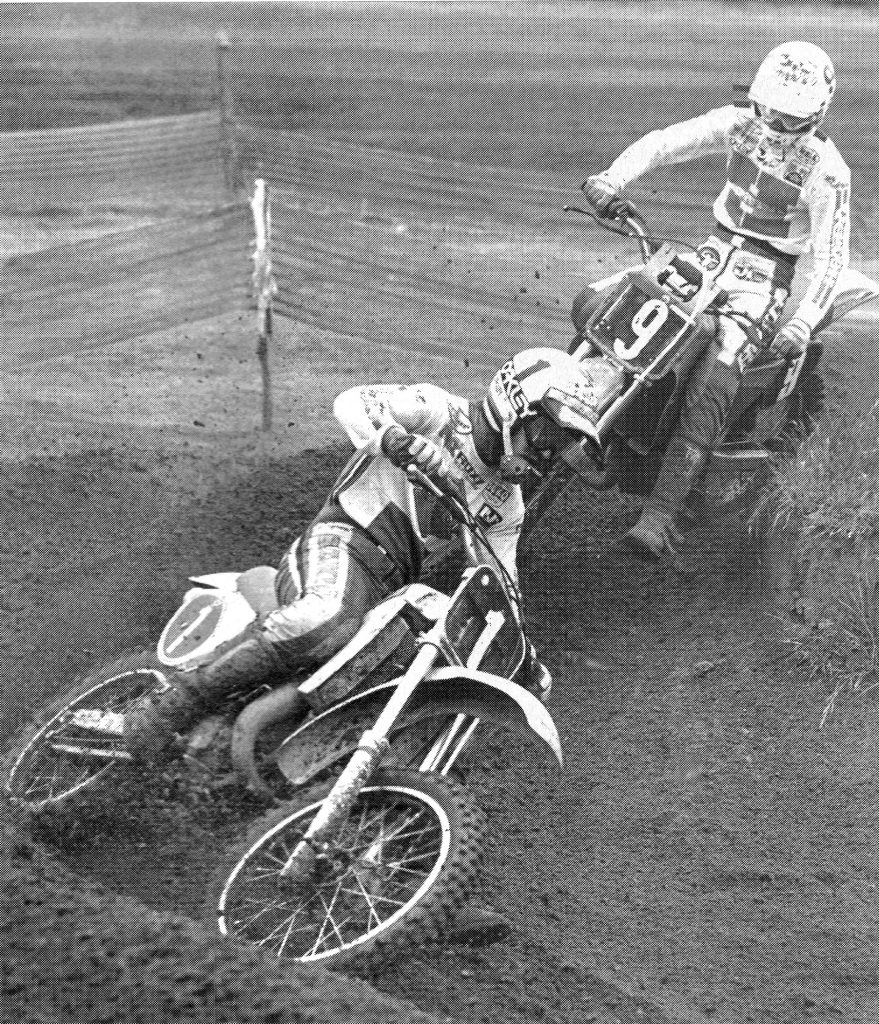

Johnny O’Mara (9) had a solid season in 1982 on a works version of the CR125R taking two overall victories on his way to second behind Mark Barnett (1) in the final 125 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Johnny O’Mara (9) had a solid season in 1982 on a works version of the CR125R taking two overall victories on his way to second behind Mark Barnett (1) in the final 125 National Motocross standings. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Up front, the 1982 CR125 added an all-new set of 38mm Kayaba forks. In 1982, these were significantly smaller than the 41mm forks found on the Kawasaki KX125, but par for the course in the 125 class. The new forks offered all-new valving and three external adjustments for compression damping, a significant upgrade for the time. There was no available adjustment for rebound control, but most forks in 1982 offered little if any external adjustments aside from air pressure. The new forks protruded 20mm less below the axle to prevent them from catching in ruts and featured 12.6 inches of overall travel.

The CR’s all-new 38mm Kayaba forks offered three levels of external compression adjustment. Despite this innovation, however, their performance was grim. Softly sprung, underdamped, and harsh in action, they were ranked the worst stock forks in the 1982 125 class. Photo Credit: Honda

The CR’s all-new 38mm Kayaba forks offered three levels of external compression adjustment. Despite this innovation, however, their performance was grim. Softly sprung, underdamped, and harsh in action, they were ranked the worst stock forks in the 1982 125 class. Photo Credit: Honda

One of the major focuses of all the CRs for 1982 was weight loss. In 1981, the entire Elsinore lineup had been disappointingly overweight. The addition of liquid cooling and the Pro-Link rear suspension ballooned the CR125’s weight by an eye-popping 18 pounds in 1981 and that added suet severely impacted the Honda’s performance on the track.

In 1982, Honda put their red tiddler on a diet and the result was a trimmer, if not exactly feathery machine. All-new brakes moved to magnesium for the backing plates and brake shoes. Magnesium was also picked for the engine side cover to shave a few ounces. All the brake levers, switchgear, mountings, and brackets were crafted out of aluminum and both front and rear wheels were redesigned to be smaller and lighter. All told, these efforts added up to a four-pound weight savings for 1982.

The motor changes for 1982 delivered a completely different powerband than the year before. Top-end power was reduced, but the CR’s motor was much stronger everywhere else. It was far easier to ride and a better motor in the eyes of most testers. Photo Credit: Honda

The motor changes for 1982 delivered a completely different powerband than the year before. Top-end power was reduced, but the CR’s motor was much stronger everywhere else. It was far easier to ride and a better motor in the eyes of most testers. Photo Credit: Honda

Visually, the 1982 CR125R was a significant upgrade in the minds of most riders of the time. The bizarre “hangnail” front fender found on the US-bound ’81 CRs was retired in favor of a much more traditional vented design and the red motor and white radiator wings were replaced with a more serious red and black motif. Much of the bodywork was a carryover from 1981, but the black motor, slimmer tank, new shrouds, and lack of a snow shovel on the front clamps changed the CR’s appearance significantly for the better.

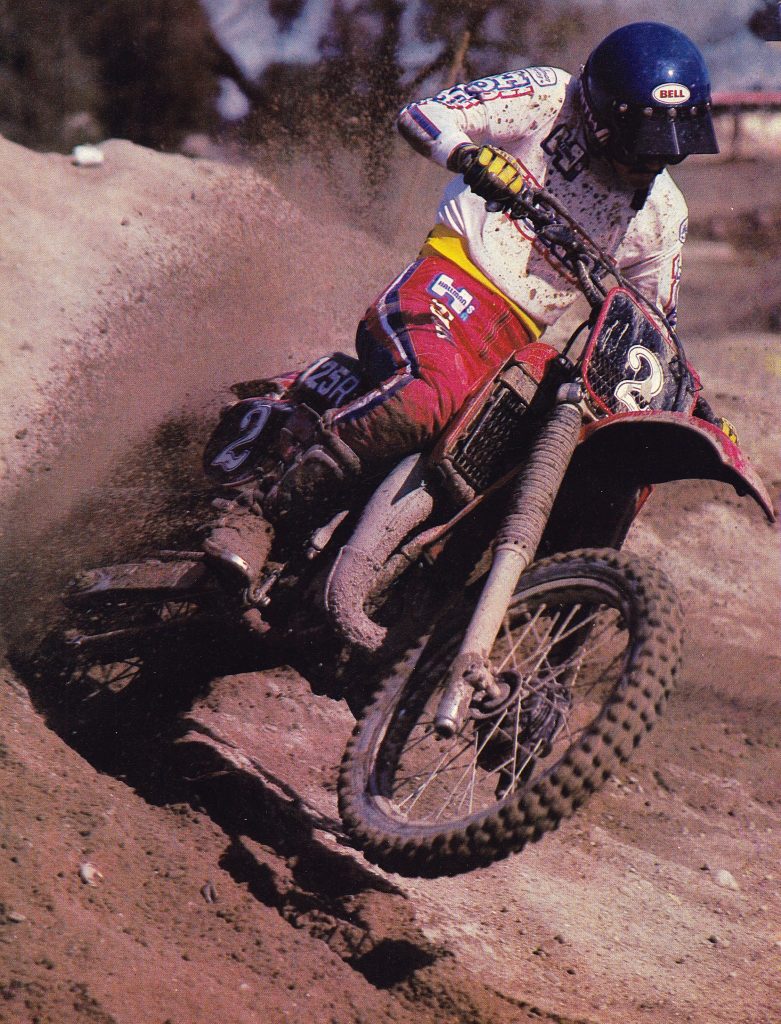

The 1982 CR125R was far from the fastest or best-suspended machine in the class but talented riders like Johnny O’Mara could shred on the nimble red tiddler. Photo Credit: Honda

The 1982 CR125R was far from the fastest or best-suspended machine in the class but talented riders like Johnny O’Mara could shred on the nimble red tiddler. Photo Credit: Honda

On the track, the 1982 CR125R was a much-improved machine. The more aggressive geometry, updated motor, and improved ergonomics turned the Honda from a back-of-the-pack performer into one of the most fun machines in the class. The modest motor updates transformed the Honda’s powerband from a gutless revver into a snappy low-to-midrange machine that came on strong down low (for a 125) and lofted the front end at will. It was quick to respond, rarely bogged, and potent through the middle. Its close-ratio six-speed transmission did a great job of keeping the Honda in its sweet spot and the new clutch was far more effective at putting that power to the ground than the year before.

For most riders, the only real complaint voiced with the CR’s motor was its lackluster pull on top. Unlike the high-strung ’81 motor, this revamped version was much happier being short-shifted rather than revved to the moon. If you kept it pinned it would keep revving but there were not a lot of ponies to be found in the RPM stratosphere. If the track was tight then the CR was in its element, but if things opened up, the Honda was at a noticeable disadvantage.

For 1982, Honda dropped the adjustable rebound damping on their shock and went with a less common adjustment for compression damping control. Most riders found this adjustment of negligible value and were highly unimpressed with the action of the overstressed rear damper. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1982, Honda dropped the adjustable rebound damping on their shock and went with a less common adjustment for compression damping control. Most riders found this adjustment of negligible value and were highly unimpressed with the action of the overstressed rear damper. Photo Credit: Honda

With its high-tech power valve, Yamaha’s YZ125 offered the most power and widest powerband in the 1982 125 class. The stock YZ was a bit overgeared but anyone who rode the Yamaha could tell its works-style motor was the fastest by a wide margin. By most estimates, the KX was second, with a punchy delivery that mimicked the Honda somewhat but offered more punch. Suzuki’s RM, the bike that dominated 125 racing in 1981, came back with an ultra-smooth powerband that was decently fast but felt disappointingly slow. When pitted against its rivals, the RM did not prove to be slow, but its lack of hit left many longing for the ’81 version of the Suzuki mill.

This left the CR125R as the head-scratcher of the 125 field. Many riders picked it as their favorite motor to ride, but their least favorite to race. It was the exact opposite of the RM125, which felt slow but was fast. The Honda felt quick but tended to get eaten up on the start and down long straights. The CR was super quick from turn to turn and easy to keep on the pipe, but most riders felt it needed more ponies on top to be competitive for serious racing.

Lightweight alloy components helped shave four pounds of unwanted weight off the CR125R for 1982. Photo Credit: Honda

Lightweight alloy components helped shave four pounds of unwanted weight off the CR125R for 1982. Photo Credit: Honda

On the suspension front, the 1982 CR125R was improved but still not particularly good compared to its rivals. The revamped Pro-Link rear suspension flummoxed many pilots with its new-fangled compression damping adjustments. Many riders felt the adjuster was a gimmick that offered no discernable difference in the shock’s performance. The new damper was set up softly and it did a good job of gobbling up small chop, but once the bumps got bigger it bottomed and struggled to keep up. Fading remained a problem with the Showa shock petering out the quickest and staying overheated the longest. Adding a stiffer spring helped with the bottoming, but the disappearing damping was something that could not easily be addressed.

At a slower pace the CR’s stock suspension did a decent job of smoothing out the track, but once the speeds ramped up and the bumps got bigger both ends struggled to keep from marring the underside of their fenders with large strips of black rubber. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

At a slower pace the CR’s stock suspension did a decent job of smoothing out the track, but once the speeds ramped up and the bumps got bigger both ends struggled to keep from marring the underside of their fenders with large strips of black rubber. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Up front, the KYB forks were even more disappointing and rated the poorest stock legs in the 1982 125 class. Like the shock, most riders found that the new three-stage compression adjuster had little to no effect on their performance. Spinning the dial did nothing to improve their harsh action, while square-edged bumps were felt right through the handlebars and none of the magazine testers were impressed with their action.

On the handling front, the 1982 CR125R was improved considerably over the 1981 machine. The all-new frame featured a much more aggressive geometry than the year before and the quicker steering was quite noticeable. The lowered radiators and slimmer tank also improved the steering feel and overall handling of the CR. Front end traction was quite good and the bike could hold the inside line with ease. For most riders, the most common complaint was the CR’s light front end, which tended to loft the front wheel out of turns. When sitting on the bike, the front end felt low, but once power was applied it liked to wheelie. The low front end made riders want to keep their weight back and this only exacerbated the bike’s wheelie-prone nature.

Serious changes to the CR’s frame geometry for 1982 added up to one of the sharpest-turning machines in the class. High-speed stability was unimpressive, but the Honda could cut under, over, and around most other machines with ease. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

Serious changes to the CR’s frame geometry for 1982 added up to one of the sharpest-turning machines in the class. High-speed stability was unimpressive, but the Honda could cut under, over, and around most other machines with ease. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

If you could get used to the light front end, then the CR was a good-handling machine. The bike felt light, despite being one of the heaviest 125s. Its snappy power, slim ergonomics, and aggressive geometry made for a bike that was responsive and fun to ride. It turned well, flew straight, and generally went where it was pointed. At speed, the aggressive rake and trail numbers had the Honda feeling quite busy and there were more than a few riders who were unsettled by the CR’s wandering nature. Like the motor, the CR’s handling made it a fun bike to ride. The quick-turning and light front end made for cool shots as you shredded corners and lofted the front wheel for your buddies, but a bit better chassis balance and a more refined suspension package would have made going fast on the track easier.

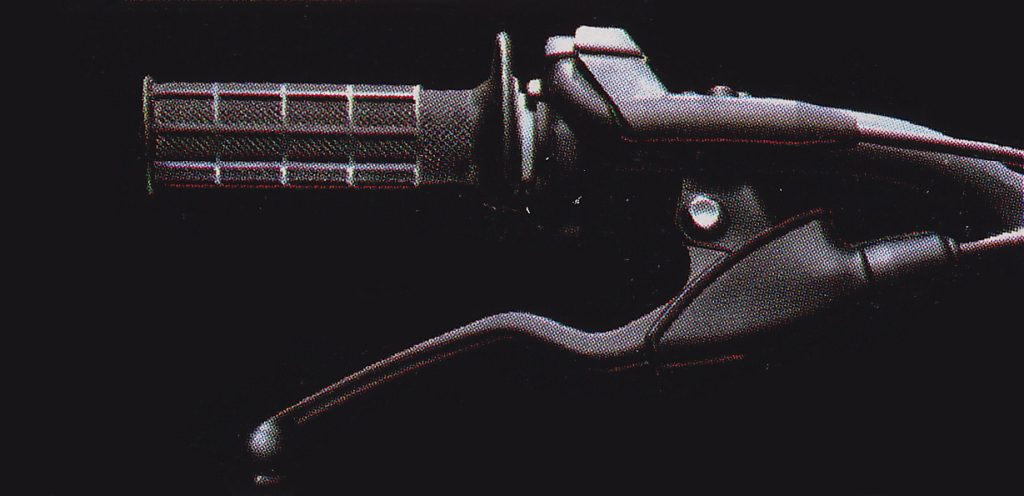

Component quality was excellent on the Honda with high-quality grips, levers, and fasteners throughout. Photo Credit: Honda

Component quality was excellent on the Honda with high-quality grips, levers, and fasteners throughout. Photo Credit: Honda

On the detailing front, the CR125R was improved but far from perfect. The 1981 machine had proven very unreliable and prone to several failures and Honda addressed many of those issues for 1982. The new Dual Flow coolant system kept the little Honda from boiling over and the revamped clutch no longer tried to take off before the lever was released. Piston and ring wear remained excessive, and it was vital to keep a close eye on the top end. If you neglected top-end maintenance, the bike would start to get pretty ratty feeling and eventually go bang. Air leaks at the intake manifold were also a common problem and this may have played a role in the prematurely expiring top ends. It was vital to properly torque the intake manifold to prevent a potentially disastrous air leak. The stock air filter was also made of recycled tissue paper so springing for an Answer, Uni, or Twin Air aftermarket filter was a good idea.

In 1982, all of the Japanese 125s had their fans, but none proved omnipotent in the final standings. Most riders felt the Honda was the most fun to ride, but its lack of suspension finesse and mediocre top-end pull hurt its appeal. The high-tech YZ125 ruled the horsepower wars but was held back by poor handling and too much pork. The Kawasaki handled the best overall and offered the most powerful brakes, but its ergonomics were odd and its powerband was too short. In the opinion of most magazine testers, Suzuki’s RM125 remained the best 125 available in 1982. Its revamped motor was rather unimpressive, but its ultra light weight, great handling, and superb suspension made it the machine to beat for hardcore 125 racing. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

In 1982, all of the Japanese 125s had their fans, but none proved omnipotent in the final standings. Most riders felt the Honda was the most fun to ride, but its lack of suspension finesse and mediocre top-end pull hurt its appeal. The high-tech YZ125 ruled the horsepower wars but was held back by poor handling and too much pork. The Kawasaki handled the best overall and offered the most powerful brakes, but its ergonomics were odd and its powerband was too short. In the opinion of most magazine testers, Suzuki’s RM125 remained the best 125 available in 1982. Its revamped motor was rather unimpressive, but its ultra light weight, great handling, and superb suspension made it the machine to beat for hardcore 125 racing. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

There were fewer reports of hoses blowing off the shock reservoir, but many riders found that the hoses continued to leak. This did not help the fading issues and serious racers found that going with aftermarket options were the best fixes for the Honda’s ongoing suspension woes. The new swingarm was much stronger than in 1981 and it no longer cracked at regular intervals. The chunky welds on the new frame were a bit amateurish looking, but it proved far more robust and willing to take punishment than the year before. The drum front brake was a far cry from the Kawasaki’s trick front disc, but it was on par with the drum on the YZ and far better than the RM’s weak front stopper. The rear drum was powerful, but many riders felt it was a bit grabby. The stock steel bars were the toughest in the class but no one cared much for the stock bend. The grips and levers, however, were the class of the field and outstanding in comfort and quality.

After several years of sub-par offerings, Honda’s iconic CR125R made major strides back toward respectability in 1982. Punchy, nimble, and fun to ride, Honda’s 125 motocross Renaissance had officially begun. Photo Credit: Honda

After several years of sub-par offerings, Honda’s iconic CR125R made major strides back toward respectability in 1982. Punchy, nimble, and fun to ride, Honda’s 125 motocross Renaissance had officially begun. Photo Credit: Honda

Overall, the 1982 CR125R turned out to be a big step in the right direction, but not quite the elite racer that Honda fans were longing for. The bike was snappy and fun to ride, but its disappointing suspension and lack of high RPM pull held it back against the cream of the 125 crop. Riders looking for the fastest or best-suspended one-two-five would have been happier riding yellow, but if you wanted a machine that was fun to ride, then the Honda had a ton to offer. Its motor was responsive, its chassis turned on a dime, and it could impress your friends with wheelies for days. The glory days of Honda’s 125 dominance were still a few years away, but the era of red tiddlers being the whipping boys of the 125 class was finally coming to an end.