For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to look back at the machine that brought Japanese dominance to the open class, the 1976 Suzuki RM370A.

In 1976, Suzuki dropped a bomb on the motocross establishment with their works replica RM’s. The all-new RM250 and RM370 were so much better than the bikes that preceded them, it almost seemed like a crime to retain the TM’s color scheme. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1976, Suzuki dropped a bomb on the motocross establishment with their works replica RM’s. The all-new RM250 and RM370 were so much better than the bikes that preceded them, it almost seemed like a crime to retain the TM’s color scheme. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Prior to the mid-seventies, the world of motocross was exclusively the purview of the Old World European brands. Brands like BSA, Husqvarna, and CZ won all the races and took home all the titles. Then in 1965, a little upstart from Hamamatsu by the name of Suzuki made the bold decision to try their hand at Grand Prix motocross racing. Initially, their new RH works racers were woefully underpowered and comically overweight. They handled poorly, broke constantly and struggled to even finish a moto in the first few years of competition. By 1969, however, they had completely transformed their program. With the RH69, Suzuki had the most advanced machine on the track, and its first World title with Sweden’s Olle Petterson at the controls. In a mere four years, Suzuki had gone from laughing stock to World Champion.

Prior to the RM370, Suzuki’s entry in the Open class was the single most infamous machine in motocross history-the TM400 Cyclone. While Suzuki tried to play off the Cyclone as the same bike DeCoster rode in the GP’s, one ride on this widowmaker was enough to dispel those notions. The introduction of the RM’s would end nearly a decade of production futility by the boys from Hamamatsu. Photo Credit: Suzuki

Prior to the RM370, Suzuki’s entry in the Open class was the single most infamous machine in motocross history-the TM400 Cyclone. While Suzuki tried to play off the Cyclone as the same bike DeCoster rode in the GP’s, one ride on this widowmaker was enough to dispel those notions. The introduction of the RM’s would end nearly a decade of production futility by the boys from Hamamatsu. Photo Credit: Suzuki

During these remarkable years, Suzuki made the decision to put a motocross machine into production for the first time. The 1967 TM250 was a virtual copy of the RH67 factory racer and available in very limited quantities to the riding public. While this bike was based on a Factory racer, it was based on a very poor factory racer, and no great machine to own or race. Unfortunately for consumers, as Suzuki‘s Factory race program improved by leaps and bounds, its production TM racers continued to be poor performers. In the early seventies, Suzuki ads touted the TMs as being direct descendants of the Factory racers of Geboers and DeCoster, while in actuality they shared not a part in common. The RHs were everything the production TMs were not: fast, light and built to win. If someone bought a TM400 expecting to get The Man’s race machine, they were in for a rude (and often painful) awakening.

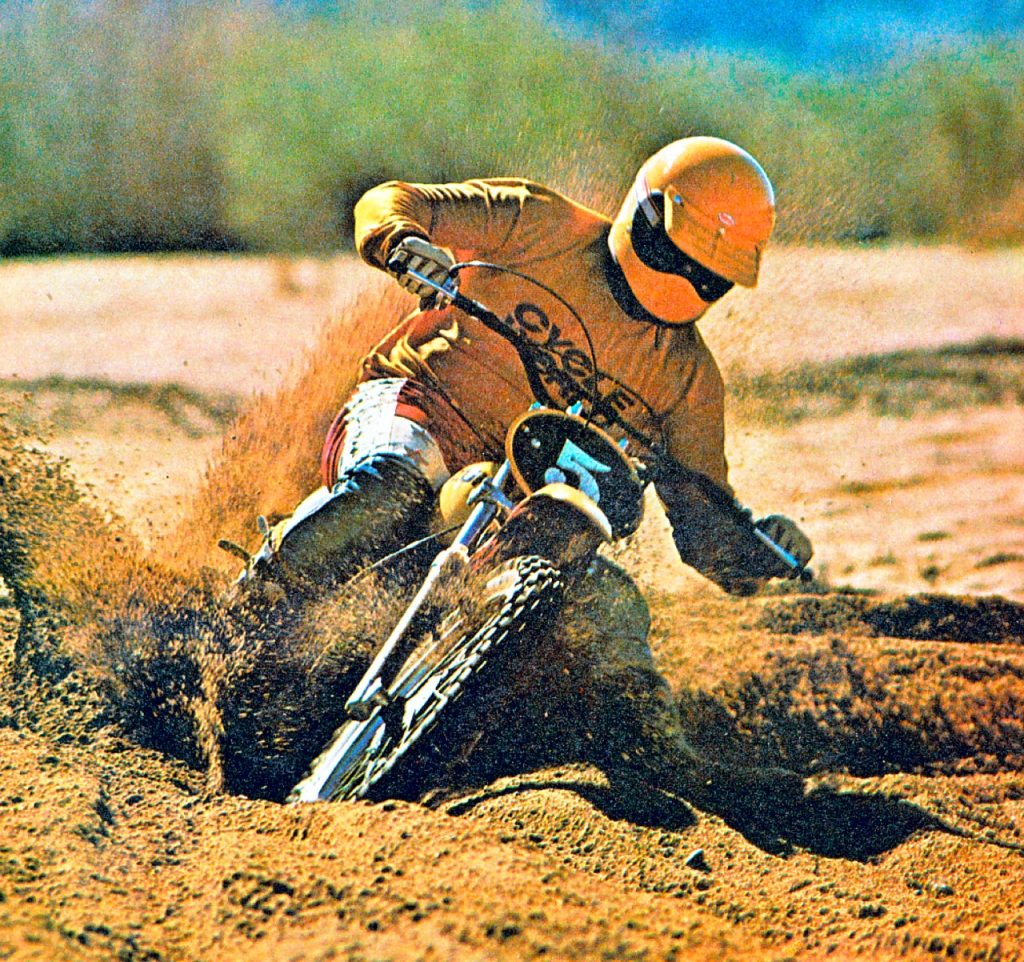

The RM370’s mill produced a torquey and strong flow of power from its 372cc’s. Low end and midrange were excellent, while the top end was merely adequate. It was not the fastest bike in the class (that honor fell to the Yamaha and Maico), but it was easy to ride and very competitive. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The RM370’s mill produced a torquey and strong flow of power from its 372cc’s. Low end and midrange were excellent, while the top end was merely adequate. It was not the fastest bike in the class (that honor fell to the Yamaha and Maico), but it was easy to ride and very competitive. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

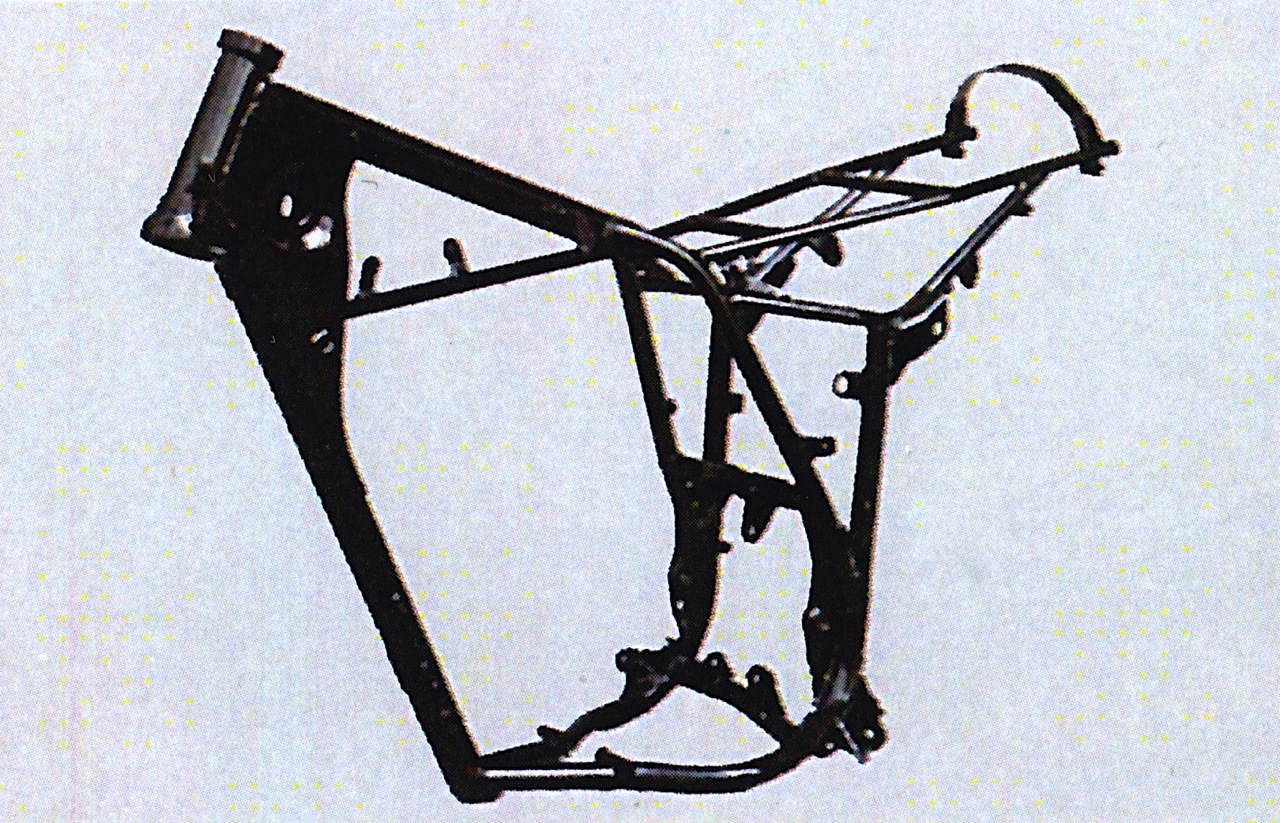

While the new RM chassis shared many of the same dimensions of the outgoing TM frame, its light and strong chrome-molly steel construction made it a much better motocross platform than its carbon steel predecessor. Photo Credit: Suzuki

While the new RM chassis shared many of the same dimensions of the outgoing TM frame, its light and strong chrome-molly steel construction made it a much better motocross platform than its carbon steel predecessor. Photo Credit: Suzuki

All that changed in 1975, with the introduction of Suzuki’s first RM125. The new RM was a revelation at the time. It offered long-travel shocks that dwarfed the performance of the class dominating Honda Elsinore and took the class by storm. For once, the works bike hyperbole held a grain of truth, and local racers could actually buy Factory bike performance in a production Suzuki. In 1976, Suzuki followed up the success of the RM125 with 250 and Open class versions of the works replica RMs. The new RM250A and RM370A looked to be nearly exact copies of the factory RH race bikes and a quantum leap ahead of the unloved TMs they replaced. With the introduction of the new RMs, Suzuki was poised to create a motocross dynasty that would dominate late seventies American motocross.

With the new RM370A, Suzuki had set out to build a no-compromise production racer. Gone was the heavy and flex prone carbon steel frame from the TM400 Cyclone, to be replaced with a genuine chrome-moly steel chassis like the Factory racers. The chrome-moly chassis was both lighter and stronger than the old frame and went a long way towards taming the old TM’s notoriously wicked handling. The suspension on the RM was all-new as well and featured massive long-travel units front and rear. The motor was a trick “power-reed” design that stole the case-reed technology right off Roger’s RN370 and mated it to a slick shifting five-speed trans. The new RM was pure performance, plain and simple.

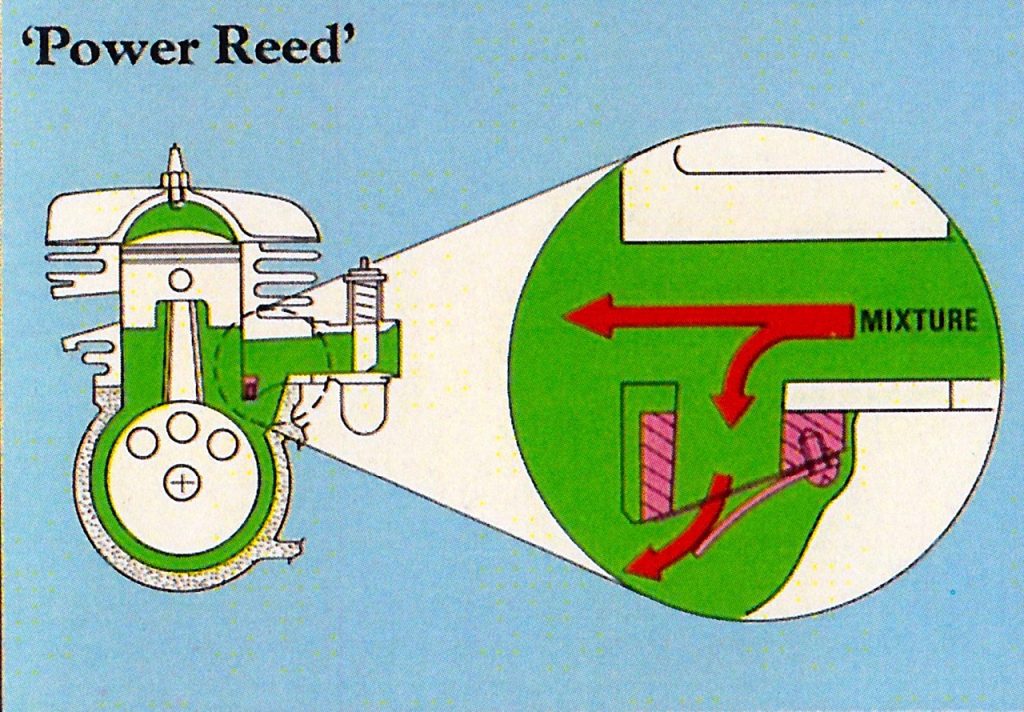

In 1976, the RM370 mill used a unique semi case-reed intake system Suzuki coined “Power Reed”. The Power Reed intake consisted of two distinct intake tracts, both designed to complement the other. While it did not quite live up to its promise powerful low-end and shrieking top-end, it did produce a solid Open class powerband. Photo Credit: Suzuki

In 1976, the RM370 mill used a unique semi case-reed intake system Suzuki coined “Power Reed”. The Power Reed intake consisted of two distinct intake tracts, both designed to complement the other. While it did not quite live up to its promise powerful low-end and shrieking top-end, it did produce a solid Open class powerband. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The heart of the new RM370A was its under-square 77 x 80mm 372cc mill. The air-cooled two-stroke single featured a 6.9:1 compression ratio, upswept works style “through” pipe and Suzuki‘s maintenance free PEI (Pointless Electronic Ignition) system. While the basic motor design was fairly conventional for the time, its intake system was unique to the RM. In 1976, Suzuki introduced an innovative semi-case-reed intake design they dubbed “Power Reed”. The Power Reed consisted of a hybrid combination of the traditional piston-port and case-reed intakes into one cylinder. On the RM370, there were actually two separate intake tracts, one above the other. The theory behind the Power Reed was to combine the excellent top-end power flow characteristics of an unobstructed piston-port intake, with the low-end response and superior torque of a reed-valve intake. By providing both intakes in one design, Suzuki hoped to achieve the best of both worlds-low-end grunt and top-end power.

While the RM’s powerband was well liked by testers, its transmission drew a lot of complaints in ‘76. The five speed’s gears were well spaced, but the detent between them was not firm enough to prevent missed shifts. Even the slightest nudge of the shifter could cause an unintended shift at the most inopportune moment. While false neutrals we common, actually fining it intentionally was often a difficult task. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While the RM’s powerband was well liked by testers, its transmission drew a lot of complaints in ‘76. The five speed’s gears were well spaced, but the detent between them was not firm enough to prevent missed shifts. Even the slightest nudge of the shifter could cause an unintended shift at the most inopportune moment. While false neutrals we common, actually fining it intentionally was often a difficult task. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

On the track, the RM370’s Power Reed motor produced a very “Maico” style of power. This meant a very tractable flow of low-to-mid-torque that was easy to get hooked up and well suited to Open class racing. Off idle, the RM picked up quickly and pulled strongly into a strong midrange blast. Past the midrange hit, the RM slowly tapered off as it approached the rev limiter. At 38.50 horsepower, the RM370 had the power to run with the best in the class in ’76. It preferred to be lugged and torqued around the track, instead of being revved like a big 250. While its output was a shade less than the Maico 450, its delivery was very similar.

With its supple suspension, sharp handling and snappy motor, the RM370A was a machine bred to win races. Photo Credit: Cycle World

With its supple suspension, sharp handling and snappy motor, the RM370A was a machine bred to win races. Photo Credit: Cycle World

While most testers loved the RM’s powerband in ’76, all was not perfect with the Suzuki mill. By far its most annoying deficiency was its five-speed transmission. The gears themselves were well spaced for motocross, but the RM’s shift detents were too small and missed shifts were common. The slightest nudge of the shifter was enough to select the next cog (if you were lucky), or a false neutral (if you were not). Once stopped, actually finding true neutral could be a chore, regardless of whether the motor was running or not. Worst of all, unlike its 250 sibling, the 370 did not get the benefit of primary kick starting. This meant it was necessary to find neutral every time the bike needed to be started. A major pain if you happened to stall the 370 mid-race.

While the alloy tank on the RM was light, it was very thin walled and easily damaged. At 2.1 gallons, it held enough fuel for a 45-minute moto. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While the alloy tank on the RM was light, it was very thin walled and easily damaged. At 2.1 gallons, it held enough fuel for a 45-minute moto. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

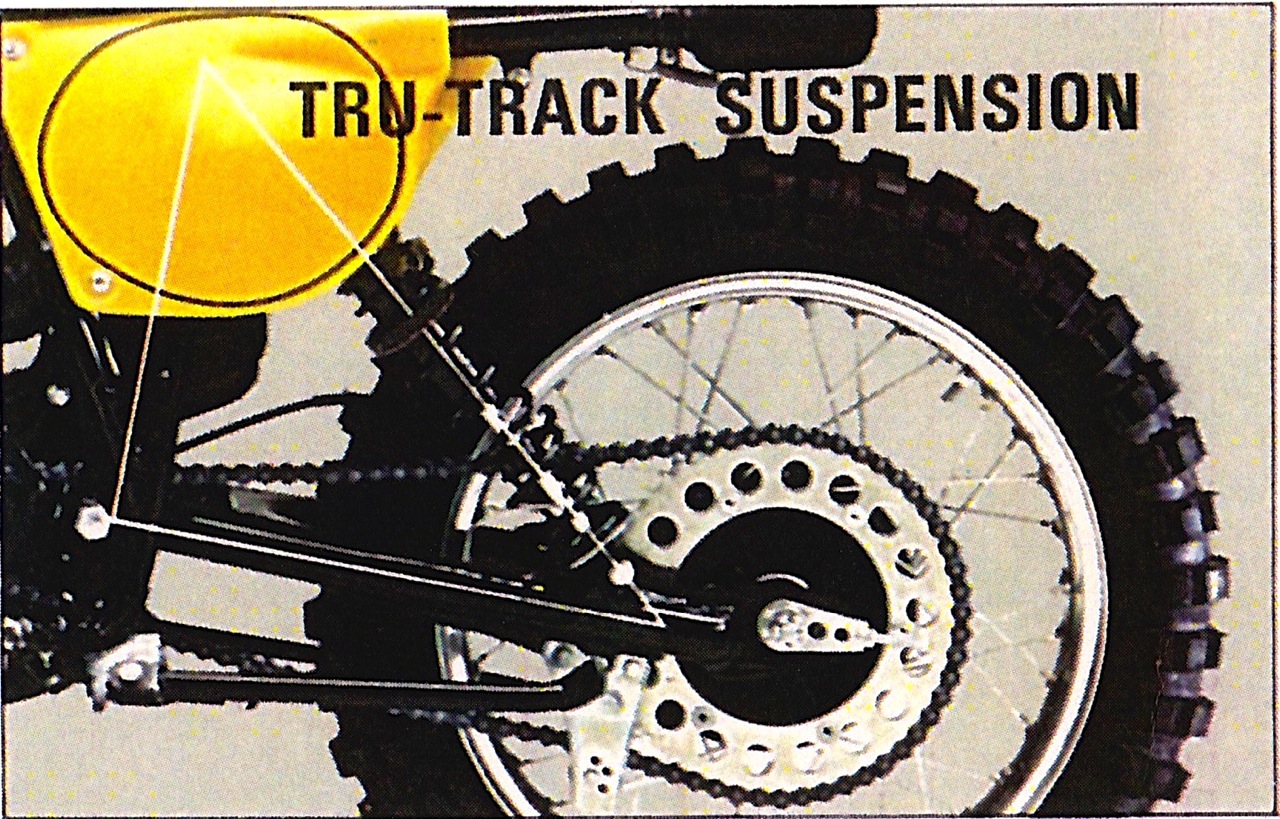

While the motor on the new RM was good, its remarkable suspension was the true star of the package. In 1975, Yamaha had introduced its radical new “Monoshock” YZs to rave reviews. The new bikes doubled the suspension travel of the YZs and ushered in a new era of suspension performance. For 1976, Suzuki struck back with a long-travel rear suspension system of their own. Unlike the Yamaha, which used a single large shock mounted to the frame backbone to gain travel, The RM stuck with a simpler and more straightforward approach (Suzuki had been offered the original Tilkens monoshock design first, but passed on it). The RM retained the dual shocks of the TM400 but moved their mounting points forward on the frame. By “laying down” the rear shocks, the RM gained more wheel travel without greatly increasing the seat height of the machine (the rear axle was also offset an inch higher in the swingarm to help keep the seat height as low as possible). The new design was called “Tru-Track” and used a set off 15.25-inch long Kayaba shocks to handle the damping. The shocks used high-pressure nitrogen gas and oil for damping, with a floating piston employed to prevent the two from mixing and causing foaming of the fluid (a major problem at the time and a cause of premature shock fade). While they lacked the fancy remote reservoirs of DeCosters’ works bike, they were considered state-of-the-art for a 1976 production machine.

The Kayaba forks on the RM punched out an excellent for the time 8.66 inches of plush travel. As delivered from the factory, they were too soft for heavy or fast riders but improved greatly with the addition of stiffer springs. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

The Kayaba forks on the RM punched out an excellent for the time 8.66 inches of plush travel. As delivered from the factory, they were too soft for heavy or fast riders but improved greatly with the addition of stiffer springs. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

With the new Tru-Track (spelling on this seems to vary, as some literature calls it “Tru-Track”, while others list the suspension as “Tru-Trac”) suspension, fine-tuning was limited to three positions of preload on the springs. There was no adjustability available to the rebound or compression damping characteristics. Since most shocks in 1976 were non-adjustable, riders typically opted for aftermarket units if better performance was desired. Thankfully for RM pilots, there was no need for an upgrade. The RM370A’s Kayaba shocks punched out 8.41 inches of travel that ate up everything in their path. They were soft initially, following small undulations and bumps with ease. Once into the latter part of the travel, they stiffened up nicely and took jumps in stride. They were both plush on small chop and well controlled in big hits. In 1976, this was the best rear end in the Open class.

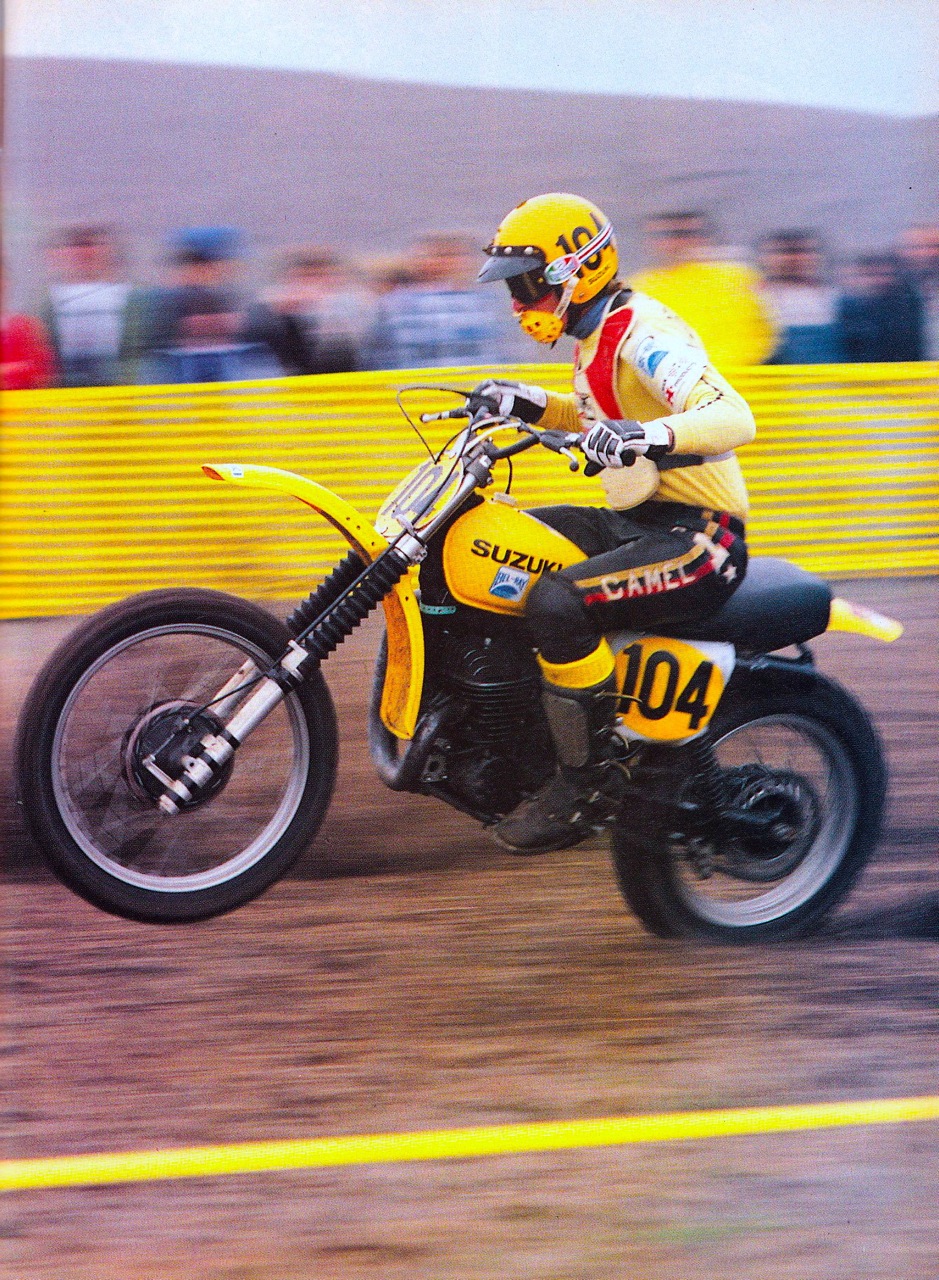

The new RM370A looked to be an exact copy of The Man’s RN370 works racer, and for once, that similarity was more than skin deep. While the RM weighed in at 20 pounds heavier than RN (due mainly to a heavy dose of titanium on the works bike), the basic machines were far more similar than previous Suzuki efforts. Photo Credit: Michael Stusiak

The new RM370A looked to be an exact copy of The Man’s RN370 works racer, and for once, that similarity was more than skin deep. While the RM weighed in at 20 pounds heavier than RN (due mainly to a heavy dose of titanium on the works bike), the basic machines were far more similar than previous Suzuki efforts. Photo Credit: Michael Stusiak

At the front, the RM offered an excellent 8.66 inches of travel from its Kayaba forks. The forks used an offset axle that placed the wheel slightly forward of the forks centerline. This was a trick that had been used by Maico for quite a while and it allowed for not only greater suspension travel, but also improved steering feel. The 370’s fork performance was considered very good, but not quite up to the standards set by its remarkable rear end. Most riders found the stock springs too soft for hard-core motocross work. They were plush over small bumps but would bottom too easily when pushed. With an upgrade in springs, they improved greatly and were considered excellent for the time. Overall, they were the second best front forks of ’76, behind only the remarkable air forks on the YZ400.

While the long travel suspension revolution started with the original Yamaha Monoshock, the first company to really make it work was Suzuki. By moving the mounting points on the swingarm back and the top shock mount forward, the RM was able to achieve a remarkable (for the time) 8.44 inches of travel. The “Tru-Track” (or “Tru-Trac” depending on where you look) rear suspension was incredibly plush and ate up rough terrain in a way never before seen on a production motocross machine.

While the long travel suspension revolution started with the original Yamaha Monoshock, the first company to really make it work was Suzuki. By moving the mounting points on the swingarm back and the top shock mount forward, the RM was able to achieve a remarkable (for the time) 8.44 inches of travel. The “Tru-Track” (or “Tru-Trac” depending on where you look) rear suspension was incredibly plush and ate up rough terrain in a way never before seen on a production motocross machine.

Once the forks were stiffened up, the RM370A became a very fine handling motorcycle. The Maico-copied front end and strong flex-free chrome-molly chassis gave the Suzuki very sharp steering response and confident feel. With its remarkable suspension and snappy motor, the RM was an easy bike to go fast on. It could dive to the inside, or rail the outside berm with equal aplomb. Whoops and jumps were taken in stride by its strong chrome-moly swingarm and Kayaba suspenders. At 225 pounds, the RM was not the lightest Open bike available in ’76, but it strong chassis and excellent suspension made it the best handling one.

While many details on the RM were a huge improvement over previous offerings, it was not perfect. Things like the cool stock plastic fork guards were a nice touch, but the flex and failure-prone front brake cable was less appreciated. Worst of all was the RM’s butter soft and fragile wheels. They required constant attention and were notorious for bending rims and snaping spokes at alarming rates. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While many details on the RM were a huge improvement over previous offerings, it was not perfect. Things like the cool stock plastic fork guards were a nice touch, but the flex and failure-prone front brake cable was less appreciated. Worst of all was the RM’s butter soft and fragile wheels. They required constant attention and were notorious for bending rims and snaping spokes at alarming rates. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While the new RM was a thousand times better than the TM400 Cyclone it replaced, it was not without problems. The most glaring of its issues were its fragile stock wheels. The Takasago rims used on the RM were butter soft and not up to the demands of motocross competition. They bent easily and required constant attention. The spokes, in particular, were a real point of concern and needed to be tightened constantly to prevent breakage of the fragile stock wheels. The other issue most riders complained about was the RM’s problematic brakes.

While this particular RM370 has had its stock chrome-molly steel swingarm replaced with a beefy aftermarket alloy unit, it has retained the stock bike’s problematic rear brake system. On the RM, Suzuki chose to go with a cable instead of a rod for rear brake actuation. This led to problems, as the cable tended to pick up a great deal of dirt and debris, binding its action over time. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

While most of the RM was all new, one area that was a carryover from the TM was the cable and guide used for the front binder. This cable was known for flexing under hard use and gave the front brake a mushy feel at the lever. In the rear, Suzuki also decided to go with a cable for actuation. This created its own set of problems, as the cable tended to pick up a great deal of dirt and debris. Once this grit was in the cable, the rear brake became hard to engage and prone to sticking on. Not a great feature.

With the arrival of the RM370A, a new standard was set for Japanese Open class performance. It was fast, handled well and was blessed with the best suspension on the track. If you were looking to win races right off the showroom floor, The RM370 was the bike for you. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With the arrival of the RM370A, a new standard was set for Japanese Open class performance. It was fast, handled well and was blessed with the best suspension on the track. If you were looking to win races right off the showroom floor, The RM370 was the bike for you. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With the introduction of the RM line, Suzuki finally had a competitive production racer. After a decade of futility, Suzuki was no longer the door mat of the motocross world. The RM370A immediately erased the memory of the infamous TM400 Cyclone and its pitiful performance. It truly was a production replica of DeCoster’s works bike and closer than any Suzuki fan had a right to hope for. The RM’s would prove to be the body blow that would finally put the nail in the Europeans coffins. What Honda had started with the Elsinore, Suzuki would finish with the RM’s, transforming tracks across America into a see of yellow in the late seventies.