For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the bike that took Mike Kiedrowski to his first AMA National title, the 1989 Honda CR125R.

For this week’s GP’s Classic Steel we are going to take a look back at the bike that took Mike Kiedrowski to his first AMA National title, the 1989 Honda CR125R.

|

|

Pro’s Choice: In the late 80’s, no manufacturer in motocross was as dominant as Honda. Their bikes captured motocross titles, shootout victories and market share at an astounding rate. In 1989, the CR’s were the most expensive bikes in every class by a wide margin, but for hard-core racers, it was hard to go wrong spending the extra cash to ride red. |

Today, parity is the name of the game in motocross. While there are certainly bikes that are better at some things than others, the days of truly terrible machines are largely in the past. That was certainly not the case in the early days of motocross, where there was often a massive gulf between the best and worst machines available.

|

|

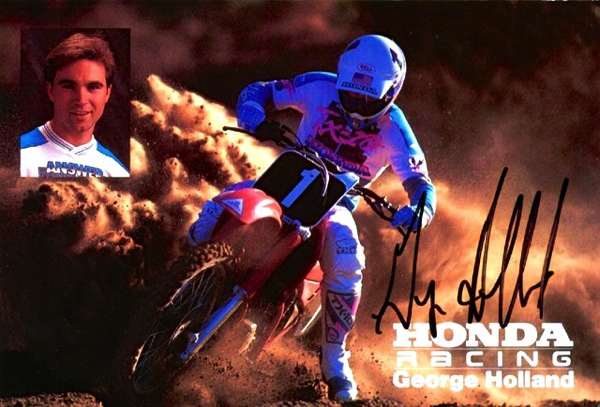

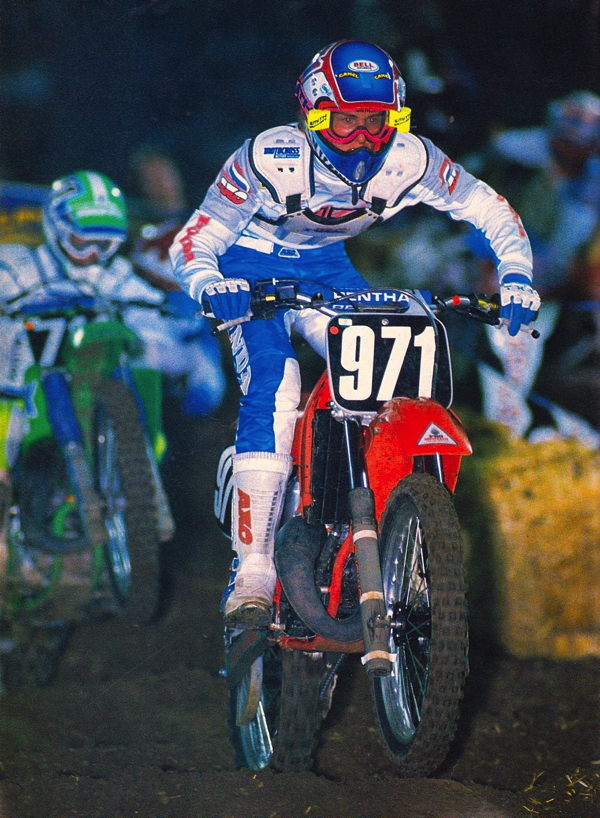

In 1989, Honda had an absolute powerhouse of a team lined up to race the all-new CR125R. The team was an exciting mix of veterans like returning 125 National champ George Holland (pictured above) and fresh up-and-comers like Larry Ward and Mike Kiedrowski. |

Nowhere was this discrepancy starker than in the mid-eighties, where riding anything else but a Honda amounted to an instant handicap. The CR’s were the fastest, sharpest handling and best-suspended bikes on the track. In 1986 and 1987, they were head-and-shoulders better than the others bikes in their classes and swept the shootout rankings in a romp.

|

|

To the moon: For 1989, Honda chose to stay with the same basic mill they had used on the CR125R since 1987. This case-reed powerhouse was soft down low, but pulled like a F-16 fighter from the midrange on up. Blessed with limitless rev and nearly endless pull, this 124.8cc rocket was loved by pros, but somewhat frustrating for the less talented. Its high-strung powerband rewarded bravado, but penalized those unwilling to stretch the throttle cable. With its poor low-end, tall gearing and propensity to bogging between shifts, the red rooster was the least novice friendly 125 of the 1989. |

In 1987, Big Red was all but invincible, but all that came crashing to a stop in 1988. A polarizing new design in the 250 class and a mellowed out powerband for the 125 had the once invincible CR’s looking vulnerable in their new blood red livery. In 1987, the CR125R had been the rocket of the class and far-and–away the best bike available. Unfortunately, the little Honda was also the victim of a rash of high profile motor failures that gave the always reliability conscious manufacturer a bit of a black eye.

|

|

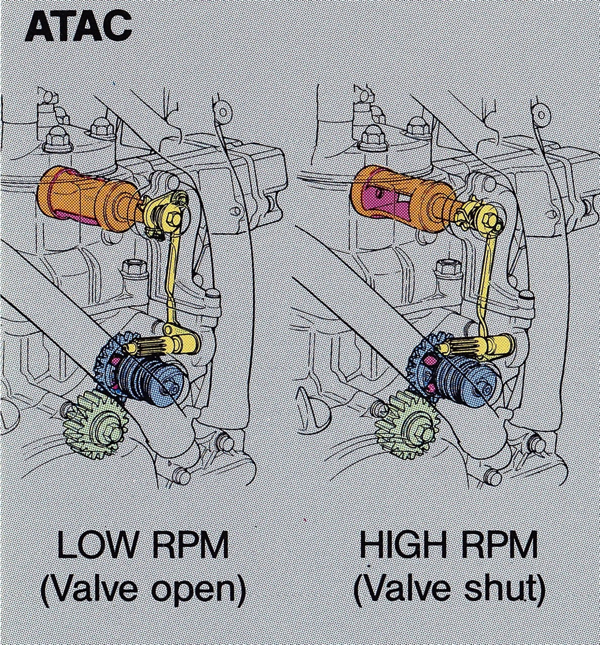

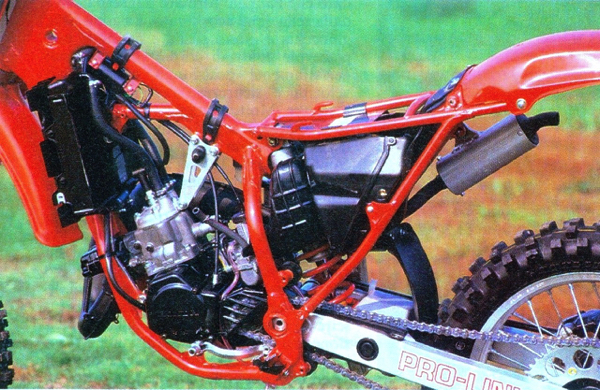

Swan song: Originally debuted on the 1984 CR125R, the ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) system promised a fat torque curve and a wide power spread, but rarely lived up to those expectations. For 1990, Honda would end up retiring the ATAC on the CR125 in favor of their more advanced HPP (Honda Power Port) design from the CR250R. |

For 1988, Honda tried to up the reliability of their eighth-liter powerhouse by reworking the cylinder, modifying the piston and lowering the compression. While this ended up improving reliability slightly, it also mellowed out the previously potent powerband. The CR was still considered by many to be the best overall 125 available, but its new “lap-time” motor was less of a hit with fans. Its long and drawn out powerband lacked hit and was less fun to ride.

|

|

MX Kied: Without a doubt, the surprise of the ‘89 125 class had to be the success of a relatively unknown kid from Canyon Country, California by the name of Mike Kiedrowski. Mike came out swinging in the new CR125R, barely missing out on the 1989 125 East Coast Supercross title to Damon Bradshaw (by a single point). In the outdoors, Mike proved he was a threat as well, shocking the field with a victory at the season opener in Gainesville. MXA Photo |

For 1989, Honda looked to recapture the 1987 magic with a majorly revised 125 package. The first order on the agenda was getting the punch back in the little 124.8cc mill. To that end, Honda looked at what they had used in 1987 and cloned it. A new cylinder mimicked the ’87’s porting and bumped the compression back up to ’87 levels. The new cylinder retained the 1988’s ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Control) system, but altered its function by closing 500 rpm later and mating it to an all-new “low-boy” exhaust. Finally, a new ignition offered one degree less advance than ’88 at all rpm’s.

|

|

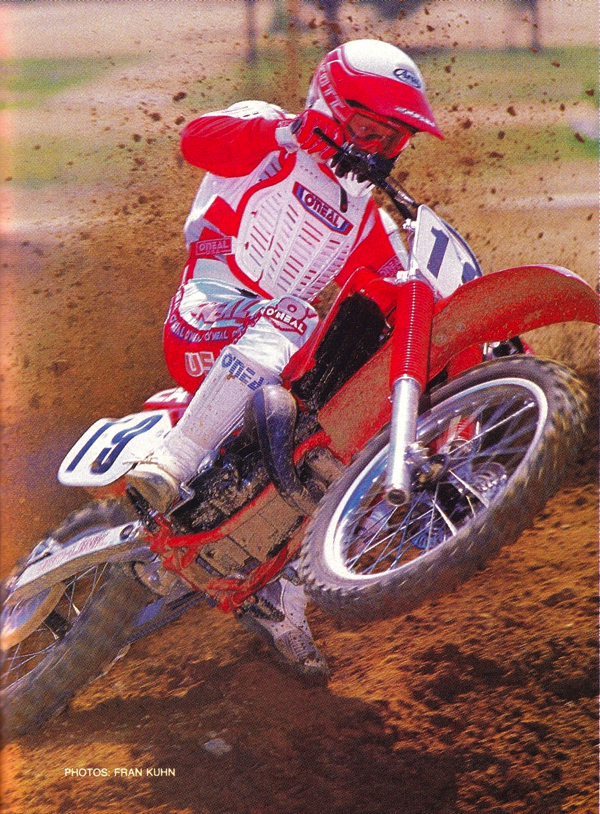

While the CR could be demanding to ride for less skilled pilots, it rewarded throttle jockeys with an unparalleled blast of ponies that never stopped pulling. Fran Kuhn Photo |

To address the reliability issues, Honda spec’d a new reed-valve that offered better sealing (leaks were a problem in ’87 and ’88) and a new Nikasil liner for the cylinder (longer life and better heat dissipation). The piston was likewise beefed up with deeper oil channels (better lubrication and cooling) and a new plated wrist pin hole (wrist pin failures were a common problem in ’87). Both the large and small end bearings on the connecting rod were increased in size and the overall motor was slightly wider and larger for 1989. In the transmission, first and second were lowered for quicker response and all the cogs were slightly wider for better durability.

|

|

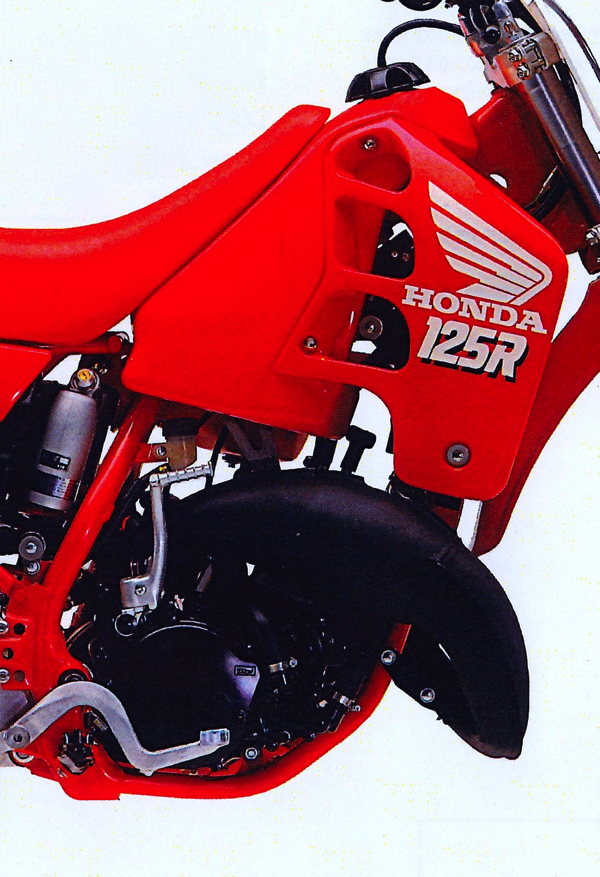

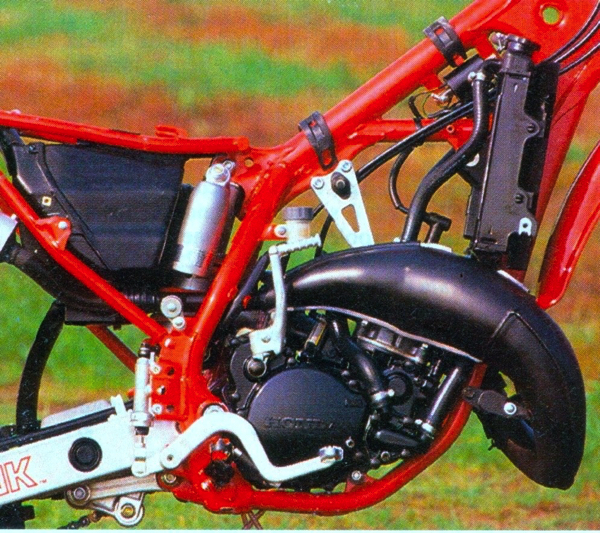

For 1989, the CR125R inherited the ’88 CR250R’s slick looks and trick “low-boy” layout. The new bodywork lowered mass and allowed much easier pilot movement front-to-aft. |

|

|

Big Bird: Another member of Team Honda’s ’89 super team was Washington’s Larry Ward. Ward would finish 3rd overall in the ’89 West Coast Supercross championship, but lose his ride to budget cuts (and the arrival of Jean-Michel Bayle) at the end of the ’89 season. MXA Photo |

To go with the new motor package, Honda spec’d an all-new chassis for red rooster. When designing the new frame, Honda looked to maintain their class-leading steering prowess, while hopefully improving rider comfort and taming some of the little Honda’s viscous headshake at speed. The new chassis featured a larger steering head tube and increased gusseting at all junctions for less flex and a half-degree less trail than 1988. While similar in geometry, the new chassis was totally redesigned to accommodate both the ’88 CR250R’s low-boy layout and new “Delta-Link” shock design. The shock itself was all-new and bolted to an entirely new swingarm and linkage. While the 43mm Showa cartridge forks were largely a carryover, all-new valving was installed and the fork was slightly shorter overall (10mm) to accommodate the new frame.

|

|

Team Honda’s biggest foe in 1989 was the Beast From the East, Damon Bradshaw. Bradshaw narrowly edged out Kiedrowski for the 125 West Coast title and dogged the red riders throughout the summer in an epic title fight that went down to the final moto of the year. MXA Photo |

So what did all of this redesigning, massaging and reworking amount to? A great CR125R yes, but not quite the second coming of the great 1987 machine. The new bike did accomplish one goal; the beloved CR125R power was back in spades. The new bike was an absolute rocket and blew the doors off of the mellow ’88 machine. Power was soft down low, before exploding in the midrange and blasting to an ear-splitting top-end shriek. Once on the pipe, no other 125 could keep the red machine in sight. It pulled harder and longer than any other machine in the class and was able to do in one gear what would take two shifts on a green, white or yellow machine.

|

|

In addition to the lower and narrower tank, the new low-boy layout lowered the pipe and radiators to better centralize mass and aid handling. |

While the new CR was unquestionably the fastest machine in the class, it was not without its drawbacks. Chief among these was the difficulty in keeping the red rocket boiling. For fast guys, this was not problem, but mere mortals often found the CR going whaaaa, whaaaa, instead of BRRAAPP! Low-end response was poor and a simple twist of the wrist was not enough to get the high-strung Honda on the pipe. For novices, the CR could be quite frustrating and the bike was prone to bogging between shifts if not sufficiently wrung out. A couple of teeth on the rear sprocket and a commitment to locking the right wrist were the best cures for this case of the bogs. While the CR was fast, its pipey nature made it a handful for slower riders. For them, the snappy RM or YZ was a better choice.

|

|

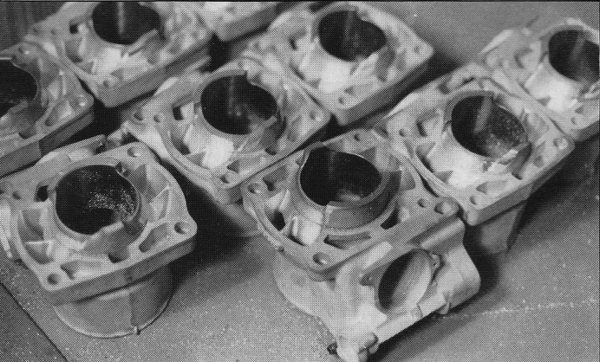

In ‘87 and ‘88, the CR125R had suffered problems with bearing failures and seizures due to air leaks at the reed-valve. For 1989, Honda addressed these concerns by enlarging the crank bearings at both ends, redesigning the piston, plating the cylinder in Nikasil and increasing the surface area of the reed-valve. |

In the chassis department, the CR may have been all new, but it remained basically the same bike it had been since 1983 – sharp in the corners, light in the air and terrifying at speed. The new low-boy layout offered a much flatter seating position (5mm higher in the middle and 8mm lower in the back) and narrower profile than 1988. The rider compartment was also roomier, with bars that were moved 15mm forward. With the new tank, came repositioned radiators and a new pipe that sat much lower on the frame. This aided cornering by lowering the center of gravity and allowing easier rider movement.

|

|

For 1989, the CR125R adopted Honda’s new “Delta-Link” rear suspension design. This new rear suspension was lighter, stronger and designed to better deal with the “supercross” style tracks that were becoming more common in the late eighties. |

On the track, the new CR was an absolute scalpel in the turns. Front end traction and response were excellent and the CR was the best machine on hardpack slick turns. In the sand and in deep loam, both the new RM and much-improved KX could give the CR a run for its money, but when traction was zero, the Honda was best. At speed, the CR continued to be busy and unsettled, with nasty headshake under deceleration. With the new Suzuki 125 adopting the Honda’s preference for carving over stability, there were only two choices available in ’89 for those with an aversion to a little (or a lot of) shimmy at speed.

|

|

Shake it to me: In the eighties, nothing else handled quite like a Honda. The CR’s were light in the air, razor sharp in the turns and evil at speed. MXA Photo |

As with any machine, the other half of the ’89 Honda’s handling equation was its suspension. For 1989, Honda chose to buck the trend toward bigger and stiffer fork legs by sticking with their tried and true 43mm conventional Showa sliders. These units had been collecting accolades since making their debut on the 1986 CR250R and Honda hoped they would prove an asset on the new machine.

|

|

Hero to zero: For 1989, Honda bucked the trend toward jumbo forks and stuck with their proven 43mm Showa conventional sliders. The best forks in motocross only two years earlier, the 1989 versions offered too much low-speed compression and a harsh ride. While better than the awful 45mm Showa inverted forks found on the CR250R and CR500R, they were still the worst forks in the 125 class. |

In 1989, front-end rigidity was the buzz phrase of the day and inverted forks were just starting to become en vogue. While only Yamaha decided to spec their 125 with the USD’s in ’89 (at least in America, international Kawasaki buyers also got USD’s), both Kawasaki and Suzuki beefed up their front ends with larger 46mm conventional designs. These larger sliders were less prone to flex and more precise when under heavy loads. With Honda sticking with the old school 43’s, CR pilots were left in the unenviable position of having the flexiest forks in the class for ’89.

|

|

Nowhere was Honda’s horsepower advantage in 1989 more apparent than in the 125 Outdoor Nationals. At some rounds, the fire-breathing Hondas claimed the top five spots at the finish, as the underpowered Kawasakis and Suzukis struggled to keep pace. Even the privateer Hondas of riders like Donny Schmit (pictured ripping the holeshot at Unadilla above) proved too much for the factory bikes of the other brands. |

While these undersized forks were certainly a small handicap, the real problem was the machine’s setup. As delivered from the factory, the CR’s Showa forks were too stiff initially and prone to deflecting on small bumps. Small, sharp impacts really unsettled the front end and prevented the bike from taking a set in rough turns. On big hits and jumps, the forks performed well, but on the holes and chop common to a motocross circuit, they were harsh and unforgiving. Under heavy loads, the CR’s forks felt less precise and the increased flex compared to its competitors was noted by all testers. Two years earlier, these forks were the unquestionably the best in motocross, but in the ultra-fast moving world of 1980’s motocross, they were quickly being left behind.

|

|

Delta-dud: Much like the forks, the new Delta-Link rear on the CR125R was better at charging than puttering. On hard impacts, it reacted well, but small bumps and holes flummoxed its Supercross bred shock and linkage. It was busy and harsh on anything short of a stadium whoop and the least liked rear end of ‘89. |

|

|

In 1989, even Jeff Stanton joined the fun on the new CR125R. At the Unadilla 250 USGP, Stanton entered the 125 support class and proceeded to wax the fastest 125 riders in the world on his little red one-two-five. Considered by many to be a 500 specialist, the newly crowned Supercross champ showed he was more than capable of pinning the throttle to the stops on the hilly New York circuit. |

Out back, Honda decided to go with an all-new suspension design for 1989. The engineers ditched the odd and fade-prone piggyback shock design from the ’88 CR125R and bolted on a new milk bottle Showa shock and Delta Link rear linkage. The Delta Link had made its debut on the redesigned ‘88 CR250R and was designed to provide better control on large hits and supercross style obstacles. In 1988, it had met with tepid approval by those not named Ricky Johnson and that trend continued for 1989. The new rear was harsh on small impacts and much happier blitzing whoops than soaking stutter bumps. If ridden aggressively, it did a decent job of taming the track, but chuck holes and chop were not in its vocabulary. Just as with the forks and motor, the shock worked better for fast guys than novices and punished those who dared to back off the loud handle.

|

|

Airtime: Finishing an impressive 3rd overall in the 1989 125 Motocross standings, Guy Cooper was another victim of the year end Honda budget cuts. At the end of the ’89 season, the Stillwater, Oklahoma native would make the jump to Team Suzuki and eventually capture the 1990 AMA 125 National Motocross title. MXA Photo |

|

|

762 to 1: At the end of the 1989 125 Motocross season, Mike Kiedrowski would end up taking home the title over Damon Bradshaw by a mere three points. Both George Holland (who pulled out do to injury while leading the chase) and Bradshaw (the fastest guy, but also the most crash happy) put up a valiant effort, but in the end, Mike’s speed and consistency would take home to the first of his four National MX titles. Mike Sweeney Photo. |

In the detailing department, the Honda continued to be the class of the field in 1989. Plastic quality, fit and feel were all top notch, with excellent ergos and the best seat in the class (although some riders preferred the taller CR250R saddle). Bolt selection, uniformity and quality continued to be the best in the 125 class and the CR was the easiest bike to tear down. Both the slick-shifting trans and excellent clutch (with a quick remove cover) were tops in the field and helped keep the red rocket roosting. In the braking department, the CR continued to offer the best levers (comfortable, forged, and twice as strong as the competition), best feel, most power and least maintenance hassles.

|

|

The dual-piston Nissin stoppers on the CR125R were by far the best brakes in motocross in 1989. These binders offered excellent power, great feel and trouble free operation. |

|

|

Overall, the new CR125R proved extremely reliable, but there were some issues with improper Nikasil plating that prompted a recall mid-year. |

|

|

In the fall, Mike Kiedrowski capped off an amazing 1989 season with a domination Team USA victory at the Motocross des Nations. |

Overall, the CR proved to be the most durable 125 of 1989. The reliability enhancements seemed to make a real difference and the bike was largely bulletproof. Piston and motor life was excellent and the bike suffered from none of the reliability issues from the two years before. While the bike was pretty bulletproof overall, there were a few small quibbles. Clutch abusers found that the basket would notch out over time and some riders suffered problems with wheel bearings failures if maintanence was neglected. Also, Honda did recall a batch of cylinders over Nikasil issues, but for the most part, the CR was very trouble free.

|

|

The 1989 CR125R was a return to glory for Honda’s tiddler. After a lukewarm ’88 CR, the ’89 brought back the horsepower and powered Team Honda to its fifth straight 125 National Motocross title. |

In 1989, Honda unleashed the ultimate 125 pro race bike. It was blazing fast (faster stock than the other team’s race bikes), handled great (razor sharp) and set up for attacking the track (big doubles, no troubles). If you backed off, it was going to punish you, but if you had the skill and cojones to keep it pinned, there was no better machine for collecting trophies in 1989.

Matthes took a look at what all the magazines thought of all the 1989 125’s HERE

For your daily dose of old-school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Twitter and Instagram -@TonyBlazier