Today, America is one of the preeminent powers in the sport of motocross. Our riders are respected for their skill and revered for their aggression. Indoors or out, America is always a threat for the win. That, however, was not always the case. Long before Stew was busting quads, American riders were getting their butts busted by the Europeans.

Starting in the UK in the early parts of the 20th century, “scrambles” (as it was then known) pitted men and machines against each other on rugged natural terrain courses throughout the English countryside. In these early days, the machines were little more than street bikes and survival was often as much of a factor as speed in the outcome. In spite of (or perhaps because of) the dangers and difficulty the sport provided scrambles caught on in popularity throughout the continent.

After the war, servicemen looking for a thrill were drawn to motorcycling and the sport continued to grow in popularity. In 1952, the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM) organized the first official European Championship for “Moto-Cross” (a combination of the words motorcycle and cross-country). This championship pitted large 500cc four-strokes against each other and was won by Belgium’s Victor Leloup on a Belgian-made Saroléa single. In 1957, the FIM added a 250cc division and renamed their series the “World Championships.”

By the time the Americans got exposed to this uniquely European sport a decade later, the boys across the pond had been perfecting their motocross skills for almost forty years. Here in the U.S., sports like dirt track, TT, and desert racing were king. For most Americans, motorcycling meant Brando on a Harley or Dick Mann in a steel-toed boot.

Eventually, however, America caught the motocross bug. We got exposed to it in the sixties and were immediately hooked. Even though we were enthusiastic, for the first few years we had a hard time even staying on the same lap with the European stars. In those early years, the wins were few and far between for the Americans. Our riders were passionate and eager to learn, but green and untested compared to the more experienced Europeans. Riders like Torsten Hallman, Dave Bickers, and Roger De Coster showed the Americans what was possible, but making it a reality would take years of hard work and perseverance.

This journey from motocross neophyte to one of the foremost powers in the sport was a long and colorful one. It is a story filled with larger-than-life personalities, twists of fate, and barely-averted disasters. The people, decisions, and events that have led us here makeup the intriguing tapestry of American motocross history. At over fifty years and counting, America’s motocross story is continuing to evolve and grow. Every race, every rider, every mechanic, and every team adds to its rich narrative.

With such an intriguing history to look back on, I wanted to take a few thousand words and chronicle the important events that got us from also-rans to all-stars. In order to tell my tale, I have broken things down into the ten most-significant events that I feel have shaped the sport we see today. Some of these events were the actions of individuals, while others were the result of external forces far beyond the control of any single man or sanctioning body. In every case, however, they were critical to fashioning the sport we see today. These are the events that shaped American Motocross.

Event #1: The Europeans Take Us To School

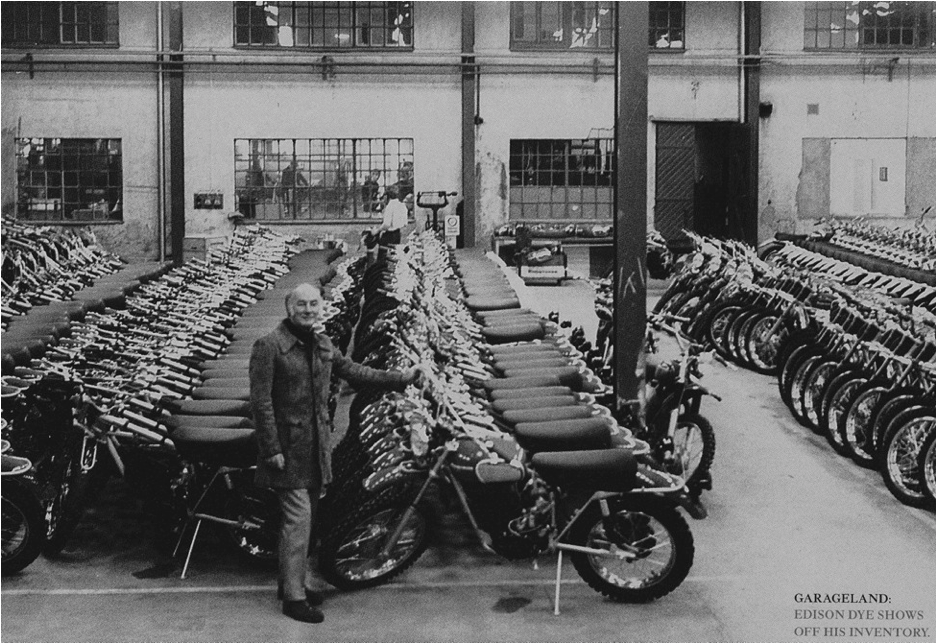

In 1966 Edison Dye had a brilliant idea to promote his Husqvarna distribution business by bringing over established motocross stars to show what the Swedish machines could really do. His idea was a huge success and led to the explosion of motocross here during the seventies. Edison Dye is the Father of American motocross. Photo Credit: Unknown

Dye brought over established Grand Prix stars Like Joël Robert to dazzle the American fans. Dave Bickers, Roger De Coster, and Robert (pictured) showed America what motocross was all about in the late 1960s. Photo Credit: Unknown

Every one of us who love the sport of motocross today owes a debt of gratitude to one man – Edison Dye. In 1966, Dye was the Western distributor for Husqvarna motorcycles. The Swedish brand, while very successful in Europe, was virtually unknown in the US market. To remedy that, Dye had the inspired idea to bring over Swedish motocross champion Torsten Hallman to participate in a few exhibition events. The exhibitions proved so successful that the following year Dye invited several more of Hallman’s Grand Prix competitors over to race as well. In order to showcase his foreign talent, Dye started in a new fall series he coined the “Inter-Am” (short for “International-American”). European motocross stars Roger De Coster, Joël Robert, and Ake Jonsson all made the trek for the inaugural series in 1967. The races were most often held on the dirt ovals and TT tracks common in America at the time. At a few events, De Coster and his GP comrades even laid out a more “motocross-style” track for them to race on (both Saddleback and High Point were originally laid out by visiting GP stars). The American fans, having never even seen a true-to-life motocross course, were blown away by the skill and speed of the GP regulars.

Dye’s Inter-Am series brought Europe’s best over every fall to compete with the young American hopefuls. It was so successful that the AMA and FIM decided they should steal the idea for their own series, the Trans-AMA. It was a raw deal for the Father of American MX.

Initially, the entire project was a huge windfall for Dye. He enjoyed remarkable exposure for both his brand and the sport that fueled it. Before long, Husqvarna would become a household name with dirt bike enthusiasts in the US. The Inter-Am races took off in popularity and Dye quickly looked to expand his series into the summer as well. Just as the series was starting to find traction, however, Dye found himself in the middle of a bitter power struggle. After witnessing the popularity of the Inter-Am series, the AMA and FIM (sanctioning bodies for US and international motocross) decided that they wanted a piece of the action. The two sanctioning bodies joined forces and together squeezed out Dye by creating a competing series they dubbed the Trans-AMA. Because the Grand Prix riders were forbidden from racing in an unsanctioned series, it spelled doom for Dye’s Inter-Am races. Today, motocross fans have largely forgotten Edison Dye; that is a tragedy because it was his vision that brought the great sport we love to this country. Without him, we might all be watching Cooper Webb slide his Harley around a half-mile in steel-toed boots.

Event #2: The Japanese Invasion

This is perhaps the most significant bike in motocross history. The ’73 Honda Elsinore changed people’s expectations for performance and durability in a stock production machine. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand

After Edison Dye introduced America to the thrilling sport of motocross, it literally exploded in the early seventies. With over a dozen brands to choose from, there was a bike for nearly any taste. Everything from a fun little Hodaka to the serious CZ and Maico was available to meet demand. Unfortunately for consumers, however, the majority of the machines available were marginal at best. At the lower end, most were little more than street bikes stripped of lights and shod with knobby tires. Even at the more premium end of the scale, the European thoroughbreds were temperamental, fragile and finicky. In the early seventies, it was up to consumers to fix their bikes’ many shortcomings and do their best to keep them running. Basically, if you were going to race motocross in 1972 you had better be good with a set of wrenches.

In 1974, Honda completed its one-two punch to the Europeans with the introduction of the all-new CR125M Elsinore. Even more than its 250 stablemate, this small-bore machine converted America’s youth to the joys of racing Japanese. Photo Credit: Honda

By the early seventies, the Japanese had made a few halfhearted entries into off-road racing with mixed results. At the professional level, Suzuki had proven dominant, taking several World Motocross titles on their exotic RN and RH racers. Unfortunately, in those days, absolutely none of that race-bred technology was actually making it back to the consumer. Suzuki’s production racers looked the part but performed poorly on the track. Yamaha was not much better with its line of converted Enduro machines. Kawasaki did have a few fast, but ill-handling offerings, however, none of them struck fear into the heart of the Europeans. Over at Honda, they were ignoring motocross completely, instead choosing to concentrate on building fun and reliable four-stroke trail bikes.

For the Japanese, all of that changed in 1973. After years of vowing to never produce a two-stroke motorcycle, Honda unveiled the bike that would transform motocross around the world; the 1973 CR250M Elsinore. This first CR was light, fast, and incredibly well-built for the time. Unlike every other Japanese machine of the era, this new Honda came ready-to-race right out of the crate. There were no lights to remove or faulty electricals to fiddle with. It was a high-performance racer with the refinement and quality people expected from a Honda.

In addition to being well built, the bike was at the front of the pack in performance as well. On the track, the CR was an absolute missile, with handling and suspension far better than anything available at the time. Overnight, motocross became more accessible to the masses. With the Elsinore, you no longer had to be proficient with a hacksaw and welder if you wanted to have a competitive machine. The CR250M was ready to win right off the showroom floor. It was a serious professional machine designed to do one thing – win races.

The 1974 YZ250A was Yamaha’s first attempt at a serious production motocross machine. The YZ was nearly twice the cost of Honda’s Elsinore and bristled with works technology. At the time this was as close to a works bike as the average rider could hope to get. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Honda’s lead would last only one year, as Yamaha and Kawasaki would both release their own serious racers in 1974. Yamaha, in fact, would leapfrog right over the Elsinore with their incredible YZ250A. The new YZ was basically a turnkey pro race bike. It made liberal use of exotic materials and featured a powerful motor with a high-tech reed-valve intake the Honda lacked. The YZ was both faster and lighter than the Elsinore, and at $1800 cost nearly twice as much.

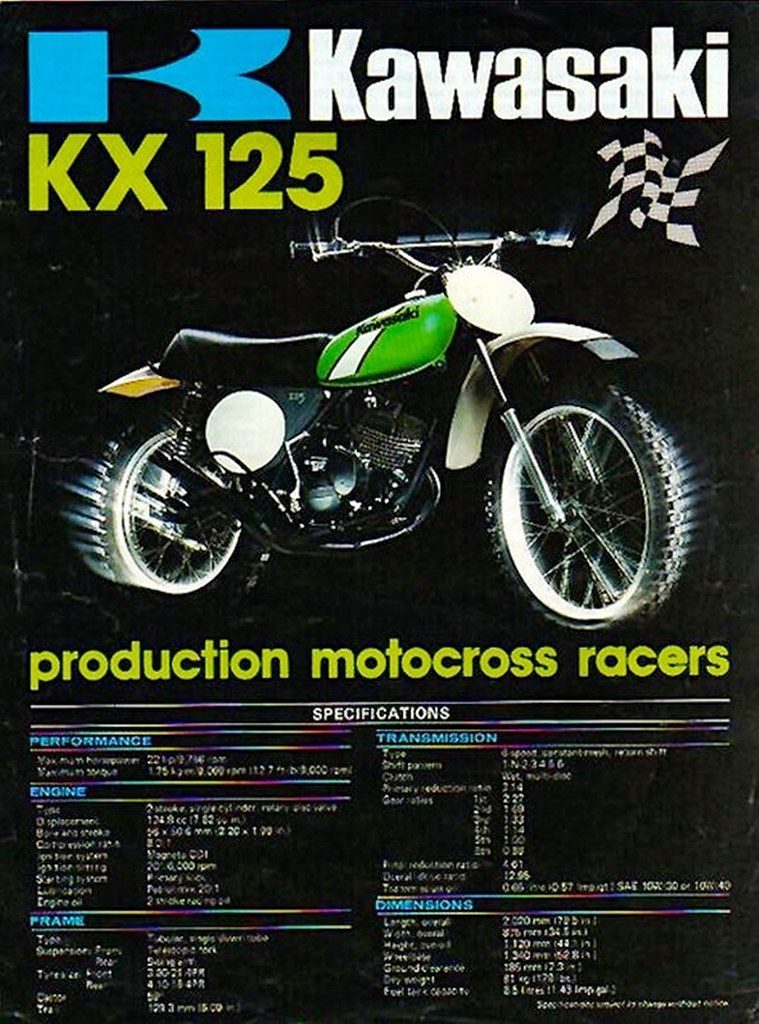

After years of offering rehashed enduro bikes as race machines, Kawasaki finally stepped up their game in 1974 by introducing their own line of serious motocross machines. The all-new KXs were far better than past efforts but initially not up to the new standards being set by Honda and Yamaha’s motocross machines. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

After years of offering rehashed enduro bikes as race machines, Kawasaki finally stepped up their game in 1974 by introducing their own line of serious motocross machines. The all-new KXs were far better than past efforts but initially not up to the new standards being set by Honda and Yamaha’s motocross machines. Photo Credit: Kawasaki

In 1974, Kawasaki also released their own new motocross racer, the KX. Unfortunately for fans of green, however, the Kawasaki bikes turned out to be not much better performers than the unloved Suzuki TMs. They were far better than past Kawasaki efforts, but not the game-changers the YZs and CRs had been. The new KX250 and KX125 were more or less Elsinore clones with worse suspension. The only real standout on the Kawasaki side was the KX125’s rotary-valve motor that provided a much easier to use power curve than the pipey Honda CR125M.

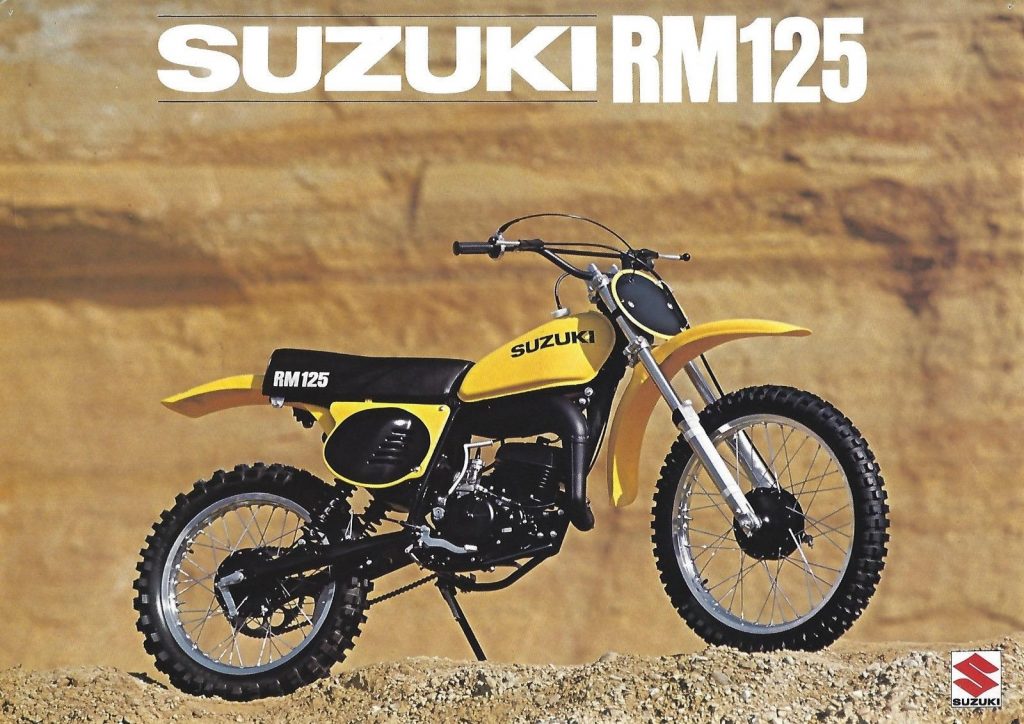

After years of sub-par production machines, Suzuki finally had a winner on its hands with its new RM line in the mid-seventies. Photo Credit: Suzuki

The real watershed year for the Japanese domination of American motocross would prove to be 1975. That year would see both the introduction of Yamaha’s incredible Monoshock YZs and Suzuki’s excellent RM line of machines. With the introduction of the RM125 in 1975 and RM250 and RM370 in 1976, Suzuki finally offered competitive production machines to the masses. After years of producing production machines that were pathetic imitations of their works bikes, Suzuki threw down the gauntlet in the mid-seventies with these groundbreaking designs.

In 1975, Yamaha dropped a bomb on the motocross industry with its game-changing YZ250B Monoshock. Photo Credit: Stefan LeGrand

Perhaps even more than the RMs, the new monoshock YZs would be machines that would come to define an era. With their ultra-long travel suspension and spacy looks, the YZs were the kind of paradigm-shifting machines that change a sport utterly overnight. Once they hit the track, every other machine that had come before was rendered virtually obsolete. With their long-travel suspension, good looks, and excellent performance, the YZs and RMs would come to dominate motocross in the late seventies, completing the shift in power from Europe to Japan that Honda started in 1973. What Europe started, Japan perfected, swinging the pendulum of motocross influence and innovation toward the East for the next thirty years.

Event #3: The Superbowl Of Stadium Motocross

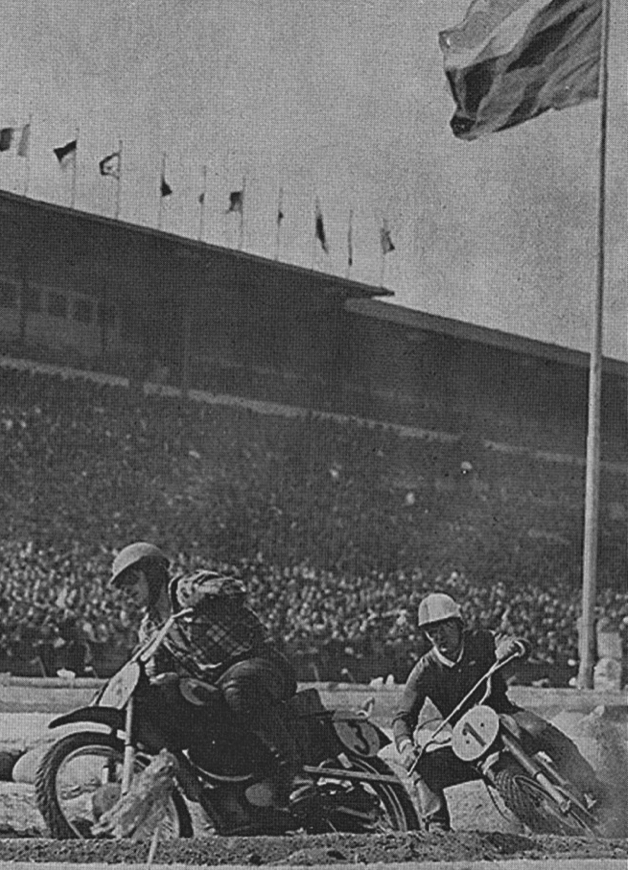

Motocross races were being held in European stadiums as far back as the late forties. Exhibition races like this one in Prague, Czechoslovakia, played to huge crowds every year before eventually being shut down by Iron Curtain politics. Photo Credit: RacerX

History is full of turning points, important people and occurrences that shape the course of events. For the sport of American Motocross, such a significant event occurred on March 13, 1971, in Daytona, Florida. On that day, the first real American stadium motocross (the term “Supercross” was not coined until 1975) was held on the infield of the Daytona International Speedway.

The genesis of this idea was a desire by the promotors of Florida’s Winter-AMA motocross series to gain a presence in the annual “Daytona Motorcycle Classics” (later renamed Daytona Beach Bike Week) week of festivities. At the time, the crown jewel of this annual event was the Daytona 200, a road race that had been taking place since the late 1930s. As they neared the thirtieth running (they took a few years off during the war years of the 1940s) of the Daytona 200, track owner Bill France was interested in adding some new events to bring a little variety to his week of motorcycle celebration.

This turned out to be the perfect opportunity for the motocross promotors; who pitched France on the idea of building a motocross circuit on the infield of the road course. France loved the idea and the first unofficial Supercross was born. While not much is actually known about this initial event, we do know the track was built by pro racer Gary Bailey (stepfather of multi-time AMA champion David Bailey) and won by Swedish import Gunnar Lindstrom in the 250 class and Cleveland, Ohio’s Bryan Kenney in the 500 class. Since the AMA Supercross series did not actually exist at this point, this first race counted instead as the last round of the 1971 Florida Winter-AMA Series.

In 1971 (this particular photo is from the start of the 1972 race), promotor Bill France added a motocross-style race to his “Daytona Motorcycle Classics” (now known as Bike Week) week of festivities for the first time. Fifty years later this is still one of the premier events in the off-road world. Photo Credit: Dick Miller

While Supercross is a uniquely American take on the Old World sport of Motocross, its origins reach much farther back than the spring of 1971. Well before Gary Bailey was burying telephone poles in the sand and Mike Goodwin was drawing up racetracks on cocktail napkins, the Europeans were setting up courses in stadiums and arenas across the pond. As far back as the 1940s, they had been racing on man-made tracks in front of thousands of cheering European fans. The first such race on record took place at Buffalo stadium outside of Paris in 1948. Promoter Pierre Bardel, always on the lookout for new opportunities, staged large motorsports meetings at the stadium every year. He would have stock cars, dirt track, and eventually, motocross motorcycles racing around the track and field oval in the stadium. His track featured several small jumps to negotiate and a very early version of a “table-top” jump that, of course, was more of a hill than a jump on forties-era motorcycles.

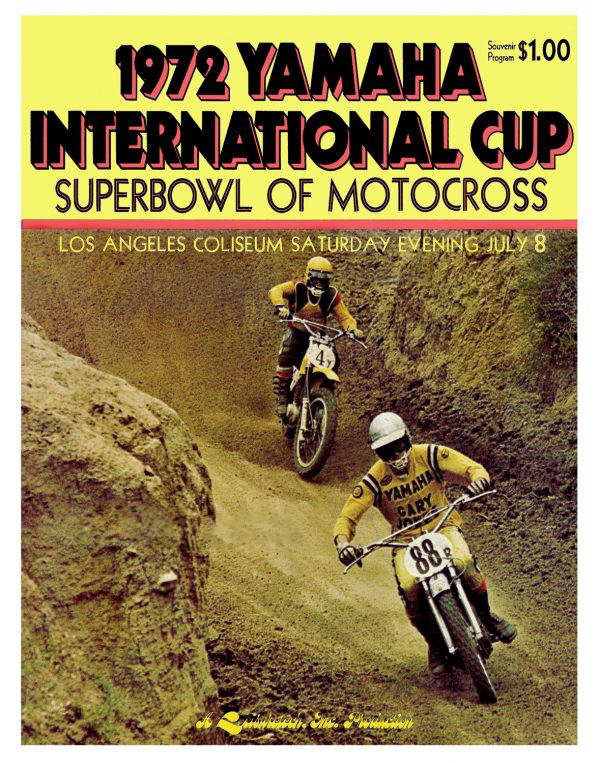

Here is the program for the inaugural Superbowl of Motocross. Goodwin’s curious sideshow would grow from these humble beginnings to be the most prestigious off-road series in the world.

In the fifties, several indoor races were staged in Czechoslovakia to coincide with their annual military parades. Massive crowds filled Strahov Stadium in Prague to attend these events. The tracks were laid out on the stadium floor and featured several man-made hills for the riders to negotiate. These one-off races, while popular, never led to any effort to stage an organized series. It would be the great American entrepreneurial spirit that would turn these motorcycling novelties into an entertainment phenomenon.

In 1972, rock concert promoter Mike Goodwin would hold his version of an indoor motocross. The “Superbowl of Motocross” would feature a man-made course laid out inside the historic Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. The LA Coliseum would remain a staple of the Supercross series for nearly three decades. Photo Credit: Dick Miller

Although the Daytona race was technically first, many people consider the race held a year later in the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum to be the first true Supercross race. Controversial rock concert promoter Mike Goodwin devised the race to be run inside the historic Olympic stadium using a 100% man-made track built on the stadium floor. Goodwin would borrow the name “Super Bowl” from the NFL for his new event (God only knows how he managed this without being sued). Playing on his concert background, Goodwin made the “Superbowl of Motocross” much more of a spectacle than your typical outdoor motocross event. Goodwin hired motorsports announcer Larry “Supermouth” Huffman to call the race action and featured crazy exhibitions like hang gliding stuntmen to entertain the crowds. In the early years, Goodwin even invited European superstars like Roger De Coster, Heikki Mikkola and Jaroslav Falta (who would actually win the ’74 event) to do battle with the Americans.

Sixteen-year-old Marty Tripes would claim victory at the first Superbowl of Motocross in 1972. Considered one of the most naturally gifted riders ever, Tripes would go on to ride for virtually every factory team in the 1970s. Photo Credit: Dick Miller

The new sport would prove hugely popular, with additional events being added to the schedule as the years went by. From the original three-race “Yamaha Superseries“, the AMA Supercross Championship would grow into the highest-profile championship in all of off-road racing. Supercross would also provide America with its first true motocross superstar in Bob “Hurricane” Hannah. Hannah would capture three consecutive Supercross titles in the latter part of the decade and set the standard for speed on the new indoor tracks.

Bob Hannah would be America’s first true Supercross superstar. He would claim three consecutive Supercross titles in the late seventies to go along with his 125 and 250 National Motocross titles. His aggressive “go-for-broke” style was perfect for the tight confines of the stadiums. Photo Credit: Dick Miller

The growth of Supercross (the name is believed to have come from a shortening of the Superbowl of Motocross name) would benefit motocross here in America in several significant ways. The first would be the consolidation of talent; unlike the European Grand Prix races and our own Motocross Nationals, Supercross brought together all the best riders into one class. That meant that our riders faced the stiffest possible competition week in and week out.

David “The Little Professor” Bailey was a perfect example of the new generation of riders raised in the technical world of Supercross. Bailey and other young Americans like Jeff Ward and Johnny O’Mara would use what they learned in the stadiums to dominate motocross throughout the eighties. Photo Credit: Dick Miller

Another benefit of Supercross would be an increase in the intensity of the racing. Motocross racing in the seventies still consisted of two long forty-five-minute motos. It was often as much about stamina as outright speed. Supercross, by contrast, was a sprint. It taught our riders a level of aggressiveness not seen in the more sedate Grand Prix races. The added intensity and increased competition paid huge dividends in improving our rider’s speed over a relatively short amount of time.

The last big change Supercross brought about was the evolution of our tracks. Since by their very nature indoor tracks had to be man-made, they could not make use of the sort of natural obstacles found on outdoor circuits. Without the benefit of big hills and off-cambers to challenge the riders, (the exception being the LA Coliseum where the track would actually go up in the stands) Supercross promoters were forced to experiment with different types of obstacles to challenge the riders and entertain the fans. Some things like the “Miller Mountain” (an early version of a tabletop jump so named for event sponsor Miller Beer) would stick, while others like mud holes would not. Track obstacles such as double and triple jumps would find their first applications inside the tight confines of the stadium floors. Supercross would eventually extend its influence far outside the stadiums. Before long, even small local tracks would begin to incorporate “Supercross style” obstacles into their designs.

In the early days of Supercross, the race promoters experimented with many types of track obstacles. One of the less popular ideas was the mud hole; fans liked them, but the teams were not as enthusiastic. Photo Credit: Dick Miller

Supercross would become the defining force shaping motocross here in America during the 1980s. Stadium racing became big business, bringing in huge crowds and major sponsors. It influenced our track’s designs and improved our riders. The added difficulty and intensity of Supercross forced our riders to hone their bike skills and improve their technique. It was the crucible that hardened our athletes into world-beaters and led to three decades of motocross dominance.

Event #4: The Original “B-Team”

For the first few years after being introduced to motocross racing, American riders were lucky to even stay on the same lap with their European competitors. Riders like Roger De Coster, Heikki Mikkola, and Joël Robert were just on a different level than our best riders. Early on, we had a few stand-out riders such as Brad Lackey and Jim Pomeroy, who could, on occasion, actually give the Euro’s a run for their money, but those occasions were few and far between.

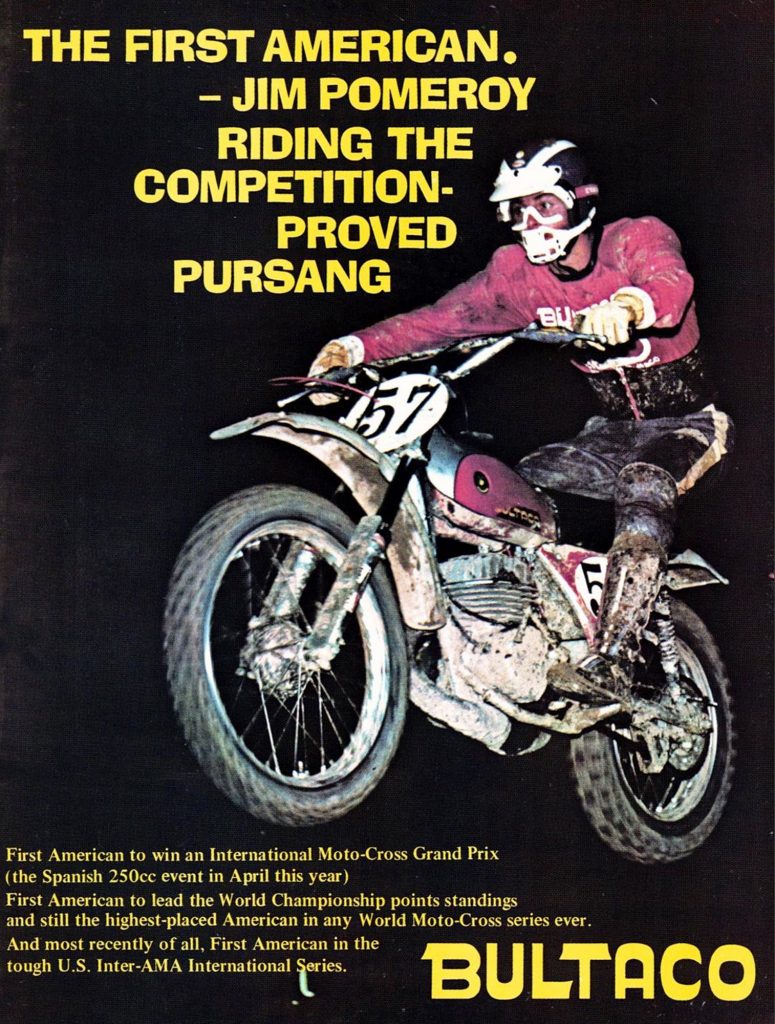

The first American to make a dent in Grand Prix Motocross was Jim Pomeroy. Pomeroy’s win at the ’73 Spanish GP was shocking to Americans and Europeans alike. Photo Credit: Bultaco

In 1973, Pomeroy would be the first American to actually beat the Euro’s straight up on their own turf. Pomeroy would pull a huge upset, riding his Spanish Bultaco to victory in the Spanish 250 Grand Prix. The victory would prove an important breakthrough for American motocross hopefuls. Conventional wisdom at the time was that the Americans actually lacked the talent to win on the world stage. Pomeroy’s victory dispelled this belief and gave hope to the thousands of young Americans looking to someday claim motocross glory.

Pomeroy’s victory, while stunning, did not lead to overnight American domination of Grand Prix Motocross. American riders like Pomeroy and Lackey would continue to race the GPs in the seventies, but find the World Motocross title elusive. There continued to be flashes of brilliance by the Americans, but the Europeans largely dominated the remainder of the decade.

Several forces finally came together to change America’s fate in the early eighties. The aforementioned rise of Supercross would greatly affect the intensity and aggressiveness of our new young riders. Also, the sheer size of the United States proved a huge advantage. Our talent pool is vastly greater than what is available in any single European country. With so many great riders competing against each other every weekend, the level of competition was inevitably going to increase.

The third factor aiding us was the retirement of the greats from Europe. The GP stars that had dominated motocross throughout the sixties and seventies were all retiring as the new decade began. De Coster, Hallman, Mikkola, and Robert were replaced by Geboers, Malherbe, and Thorpe. These new breeds of European superstars were great, but did not enjoy the same air of invincibility their predecessors had. America’s new stars of the eighties did not view these European competitors in the same light as their seventies counterparts had.

Every bit as surprising as Pomeroy’s victory in 1973 was that of LOP Yamaha’s Marty Moates in 1980. Moates’ amazing win at the 500 USGP was a real signal that things were changing in the world of international motocross. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The first sign that things would be different going forward took place on June 22, 1980, when long-time privateer Marty Moates stunned the motocross world with an incredible victory in the 500 US Grand Prix at Carlsbad. It was the first time an American had been able to capture the overall victory at the prestigious event. The question at the time was – did this victory signal a real changing of the guard, or like Pomeroy’s Spanish win, was this just another aberration? The real answer would come one year later in Beilstein, West Germany when Team USA would score one of the largest upsets in the history of motocross.

Quite frankly, America’s riders have always enjoyed a bit of a love-hate relationship with the yearly Olympics of Motocross. Over the last fifty years, our participation has been a “hit or miss” affair. After finishing a very respectable second in 1974 and 1977, we declined to even send a team in 1979 and 1980. Often our teams were poorly organized and, just as often, our riders were largely disinterested.

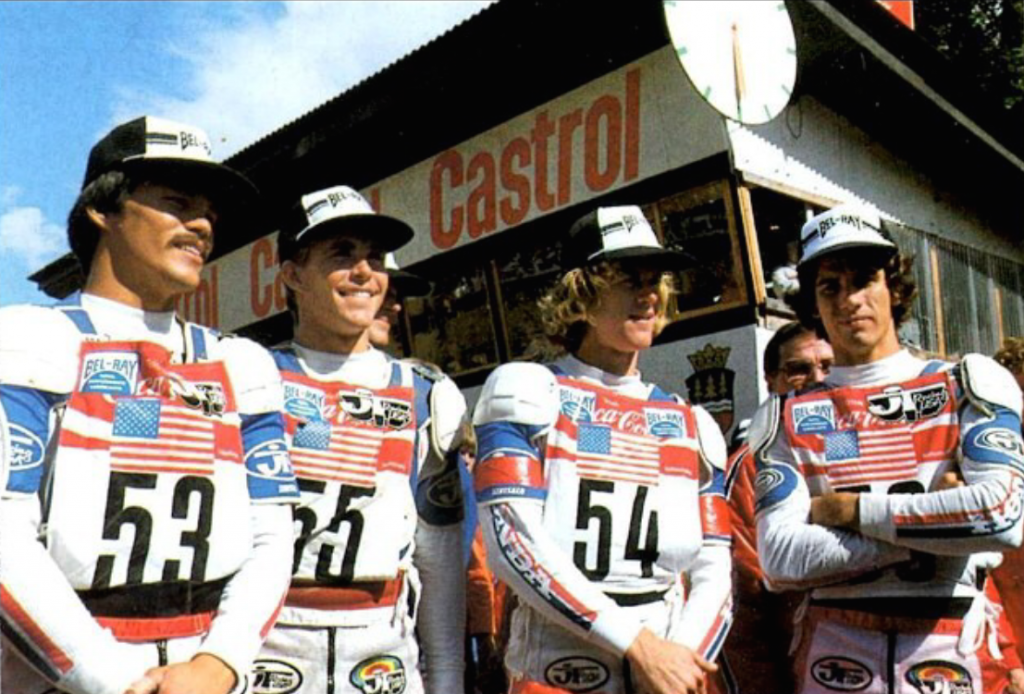

Johnny O’Mara and his teammates were on fire in Germany at the Motocross des Nations. The victory would propel the entire team to international stardom. Photo Credit: Racer X

After missing the two previous years, a grassroots effort sprung up to field a team for the ’81 event. Dick Miller of Motocross Action Magazine and Larry Maiers of Hi-Point Racing Products (also later to be known as the host of Motoworld and Supercross on ESPN) would be the driving force behind the effort. Maiers and Miller hoped to raise the $20,000 needed to fund the effort largely by selling t-shirts. Miller even got a commitment from the big four Japanese manufacturers to match their fundraising effort. The hope was to finally send a properly-funded effort to the event consisting of our top riders at the time: Bob Hannah, Kent Howerton, Mark Barnett, and Broc Glover.

The fundraising ended up being a tremendous success, but when approached, all of our best riders declined to participate. For once we actually had the money, but no team willing to go. At the last minute, Roger De Coster would come to team USA’s aid. De Coster (who the year before had moved to Honda from Suzuki) was someone who understood the importance of the des Nations and convinced his bosses to volunteer their whole team for the event. Honda agreed to send Chuck Sun, Donnie Hansen, Johnny O’Mara, and Danny LaPorte, plus their motorcycles and a full crew of mechanics to Europe for the back-to-back Trophée and Motocross des Nations.

America’s 1981 Motocross (500) and Trophée (250) des Nations victories were one of the greatest upsets in the history of motocross to that point. After America’s top riders declined to go, Roger De Coster volunteered the whole of Team Honda for the event. The team of Johnny O’Mara, Chuck Sun, Donnie Hansen, and Danny LaPorte dominated both events much to the shock of European fans. It would be the start of thirteen consecutive wins for the American team. Photo Credit: Unknown

When Europe got a look at our “B-team” they predicted another European rout of the Americans. With our best riders at home, it seemed impossible for us to win. Amazingly, however, the team of O’Mara, LaPorte, Sun, and Hansen did more than win – they dominated. At the Trophée des Nations (250cc machines) Team USA destroyed the field by such a large margin that if all of Europe had been on the same team we still would have won. One week later at the Motocross des Nations (500cc machines) we once again prevailed over the world’s best. It was an incredible victory for the untested riders.

After 1981, no American would view international motocross the same. The few victories we had enjoyed leading up to 1981 had cracked the European rider’s aura of invincibility, and with the victories in Beilstein and Lommel, we had shattered it completely. Within a year of the ’81 victory, Americans would hold the World Motocross title in both the 250 and 500 classes. In 1982, Brad Lackey would finally capture his long-sought 500 championship, with ’81 MXdN hero Danny LaPorte making it two for the stars-and-stripes with a victory in the 250 class.

After 1981, Team USA would go on an incredible win streak of thirteen straight des Nations victories. Over the next decade, the rules, riders, and venues would change, but America’s riders would continue to come out on top. In 1994, the streak would finally come to an end, but by then, there was no doubt what country dominated motocross on the world stage. What Johnny O’Mara, Chuck Sun, Donnie Hansen, and Danny LaPorte did in 1981 was change the landscape of the sport for a generation. Before their victory, America’s riders looked at the world’s best and wondered if they could win. After ’81, however, there was no question; we were the best.

Event #5: The Death Of The Works Bike

The King of the works bikes, this 1985 Factory Honda RC250 ridden by Johnny O’Mara was the absolute pinnacle of factory bikes raced here in the US prior to the AMA Production Rule. Everything on this bike was 100% custom built and tailored specifically to the rider’s preference. Estimates vary wildly, but some placed the cost of each one of these one-off machines at well over six-figures. Photo Credit: David Dewhurst

Within the world of motorsport, Motocross is highly unique. While all forms of racing require skill, no other discipline requires its participants to have the reflexes of an MLB hitter, the endurance of a soccer player, the strength of a middleweight boxer, and the fearlessness of a bull rider. In motocross, the rider is by far the most important part of the winning equation. Unlike most other forms of racing, a sub-par machine does not guarantee a sub-par result. In motocross, skill, desire, and fitness can sometimes trump mediocre equipment.

While motocross is far more rider-dependent than most other forms of motorsport, the machine does matter. At the absolute elite level, tire choices, shock settings, and careful prep can often mean the difference between a first and a fifth. There is a reason that Eli Tomac uses $20,000 forks on his bike, and it is because he can go fast enough to actually need them. The simple fact of the matter is the best guys will always have the best stuff and the also-rans will have the leftovers.

That being the case, it begs the question, why do we have a production rule? If Cooper Webb is going to beat 99% of the world’s riders on whatever he rides anyway, why handicap him with a production machine? The answer to this question is a complicated one that has as much to do with politics as race wins. It is a question that can trace its origins all the way back to the very beginning of motocross in America.

In the early 1970s, the motocross bikes you bought off the showroom floor had absolutely nothing in common with the machines being raced by the factory teams. The only thing the works bikes of Roger De Coster and Marty Smith had in common with a production bike was the color of the tank. In those days, race teams and production teams were completely different operations and rarely even shared information. The production bikes were developed completely separately from the race team bikes and even produced in different locations. It was a crazy system where a factory works bike could cost twenty to thirty times the cost of a production machine.

Pure Unobtanium: Taken in the context of their era, the 1972 factory Suzukis may be the most advanced motocross machines ever built. At a feathery 168 pounds ready to race, this RH72 of Joël Robert weighed a whopping sixty-pounds less than a production TM. Photo Credit: Terry Good

In the early seventies, manufacturers like Suzuki and Yamaha were at the forefront of the works bike craze. Early Suzuki and Yamaha factory bikes were literally rolling works of art built from aluminum, magnesium, and titanium. Honda was a few years behind its Japanese rivals initially, but once Big Red committed, they went all-in. Within a few years, Honda began outspending the other Big Four competitors hand-over-fist. As motocross entered the eighties, there began to be a real discrepancy between the works machines of Honda and its rivals. At a time when Honda’s race budget began approaching the GNP of a small county, the other manufacturers were forced to start cutting back.

In the early seventies, Yamaha was at the forefront of works technology. This ’73 YZ637 owned by collector Terry Good was the first bike to feature Yamaha’s long travel Monoshock rear suspension. It took Haken Andersson to the 250 World Title and demonstrated Yamaha’s leadership in motorcycle design. Photo Credit: Frank Melling

Yamaha, in particular, started to feel the pinch in the early eighties. After years of being a leader in works bike design, a recession back in Japan forced the brand to scale back its racing program. The effects of Yamaha’s cutbacks were immediately felt by the race teams here in America. Just as Honda was pushing forward with some of the most amazing designs of the era, Yamaha was pulling back and looking to cut costs. In 1984, this cost-cutting culminated in Yamaha’s decision to shutter its works bike program entirely and campaign production machines.

With Yamaha racing production machines, they were at an incredible disadvantage to their Japanese rivals. Honda, in particular, was pushing the envelope of design with ultra-trick machines that cost many times their production equivalents. Unwilling (or unable) to participate in this corporate one-upmanship, Yamaha turned to the AMA for relief. Taking a populist approach, Yamaha made the case that Honda’s exorbitant spending was bad for the sport and unfair to the privateer riders (never mind that the best riders would always get the most support); it was a winning angle to take with the public and the AMA.

After years of racing some of the most advanced bikes on the track, Yamaha took a step back in 1984 and put its race team on production machines. Amazingly Rick Johnson (pictured) and Broc Glover were still able to capture the ’84 250 and 500 National Motocross titles on bikes that were light years behind their competition. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

The result of this petition was the AMA Production Rule. This rule went into effect in 1986 and effectively put an end to the works bike era in America. Under the new rule, all racing machines had to at least begin as a production machine. There were allowances for suspension upgrades and some internal motor modifications, but the basic motor and frame designs had to remain largely unchanged. This was a far cry from the previous years when the only real limitations were displacement and budget. If you could afford it, you could race it.

Initially, this change was seen as a huge blow to Honda, but ironically, it would turn out to be anything but. Perhaps serendipitously, or perhaps because they saw the writing on the wall, Honda introduced the most dominant line of motocross machines the sport had ever seen in 1986. From top-to-bottom, the CRs were the class of the field and actually ended up giving Big Red even more of an advantage than they had enjoyed in 1985. On the new production-based CRs, team Honda ended up sweeping every class in 1986. Ricky Johnson, David Bailey, Johnny O’Mara, and Micky Dymond dominated the competition and delivered Honda their most impressive season ever.

It was no secret that the Production Rule was aimed squarely at Honda and its exorbitant race budget. Ironically, the change to production-based machines in 1986 led to Honda enjoying its most dominant year ever. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The Production Rule continues to be controversial to this day. The one thing it most certainly did was raise the quality of production machines available to average riders everywhere. Today’s bikes are better than they have ever been and some of the credit for that probably does go to the Production Rule. The one thing it did not do, however, was turn the privateers into factory beaters overnight. Even though everyone theoretically starts out on equal footing, the best riders are always going to get the most support and receive the best equipment. In the end, it does not matter if those part are “works” or production-based.

The advent of the Production Rule in America did not stop the development of exotic works bikes, it just moved them out of the AMA series. Machines like this super-trick alloy perimeter-framed Yamaha continued to be raced in Europe and Japan well after the Production Rule went into effect in the US. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

Even today, it remains an open question whether the Production Rule actually lowered the cost of racing. When the regulation went into effect, Japan just reallocated their R&D dollars to other markets where there was no restriction on race development. While we raced production machines, the Japanese factories continued to develop and test exotic one-off machines in Europe and Japan. In the end, true works bikes did not go away – they just left the USA.

Whether you believe the Production Rule was beneficial to racing or not, there is no denying it had a powerful effect on the sport. On the downside, the loss of the exotic factory bikes certainly took some of the color out of pro racing here in America. On the upside, however, it did put pressure on the manufacturers to improve their production machines. Today’s bikes are better than ever and capable of out-performing anything the Japanese skunkworks could have produced a few decades ago. As to whether it actually improved the racing, the answers are less clear.

As it has been since Brits first started scrambling all those years ago, the best riders invariably win regardless of their equipment. Works or production, motocross is more about the man, not the machine, and no amount of political wrangling is going to ever change that.

Event #6: The French Connection

Easily one of the most talented riders ever to throw a leg over a motorcycle, Jean-Michel Bayle could do things on his CR250R mere mortals only dream of. If Bayle had stayed in Europe, he probably could have dominated the Grand Prix racing for a decade. Photo Credit: Moto Verte

One of the fundamental changes that took place in the sport of motocross during the eighties was a diminishing in the prestige of the World Motocross Championships. This trend began with America’s upset victory in 1981 and continued to grow throughout the eighties. With every American MXdN and USGP victory, the importance of the Grand Prix races was lessened in the minds of many. After four decades as the world’s premier off-road motorcycle racing series, the GPs started to feel like a second-tier championship.

This massive shift in motocross power had a profound effect on the sport both here and abroad. Racers here in America no longer looked at the Grand Prix aspirationally. Instead, the GPs became more of a second-chance series for US racers that lost their ride or were out of options. In Europe, the World Championships were still prestigious, but by the late eighties, that luster was all but gone to riders and fans here in the US.

To say Bayle was misunderstood here in America would be a huge understatement. The enigmatic Frenchmen was at times standoffish and difficult to relate to. American fans never warmed to his quiet personality and often booed him for no reason. To this day Bayle remains one of the more mercurial figures in motocross history. Photo Credit: Mike Sweeny

To say Bayle was misunderstood here in America would be a huge understatement. The enigmatic Frenchmen was at times standoffish and difficult to relate to. American fans never warmed to his quiet personality and often booed him for no reason. To this day Bayle remains one of the more mercurial figures in motocross history. Photo Credit: Mike Sweeny

As the ascendancy of Supercross increased, it became apparent even to many hard-core Europeans that America’s series was stealing much of the mindshare of the fans. Events like the Bercy Supercross played to rabid crowds of French fans who packed the arenas trying to get a glimpse of the stylish Americans. New heroes like Ricky Johnson, Jeff Ward, and Ron Lechien enjoyed the same type of adoration men like De Coster, Robert, and Hallman had experienced two decades before.

With Supercross firmly in place as the premier off-road racing series in the world, it was going to take a new type of Grand Prix rider to swing the pendulum back to Europe. To do that, Europe would need to find a rider who was as comfortable flying through the night sky of Anaheim as he was negotiating a tricky High Point off-camber. A rider of such uncommon talent that could come to America and beat the Yanks at their own game. A rider just like Jean-Michel Bayle.

A native of the town of Manosque in southeastern France, Bayle was a product of a French motocross culture that revered the Americans and their skill at Supercross. Far more than any of the other European countries, France was quick to embrace the sport and its uniquely American flair. In 1984, Bayle entered the Bercy Supercross in Paris in the mini support class and was amazed by the speed of the American riders. After seeing his GP heroes firmly trounced by the US stars, the young Frenchman vowed to learn everything he could about Supercross so someday he could go to the US and race the Americans.

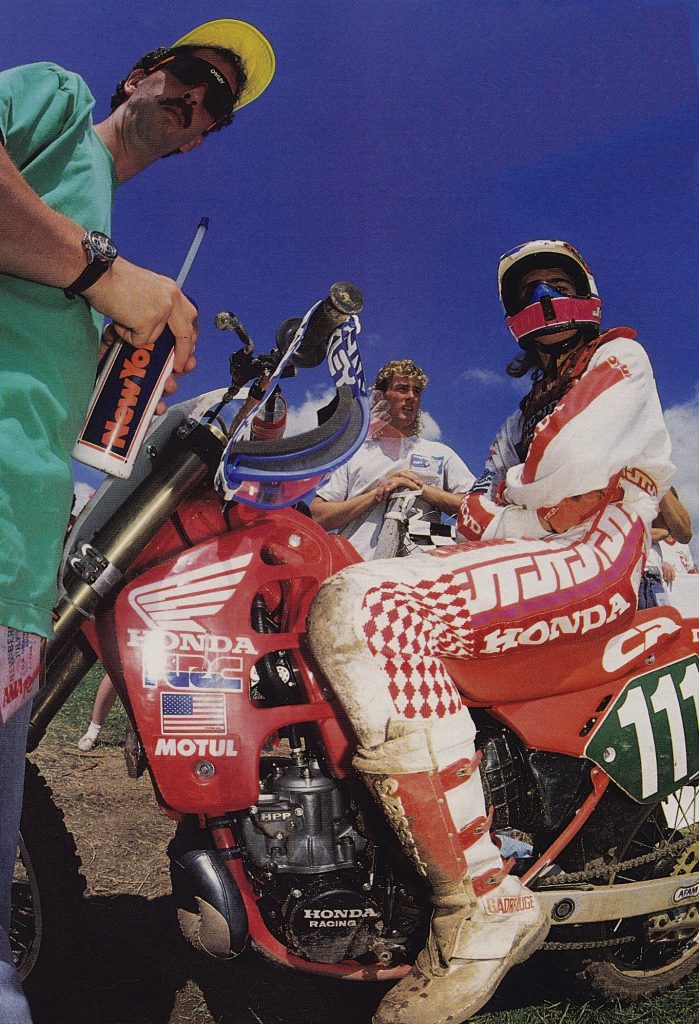

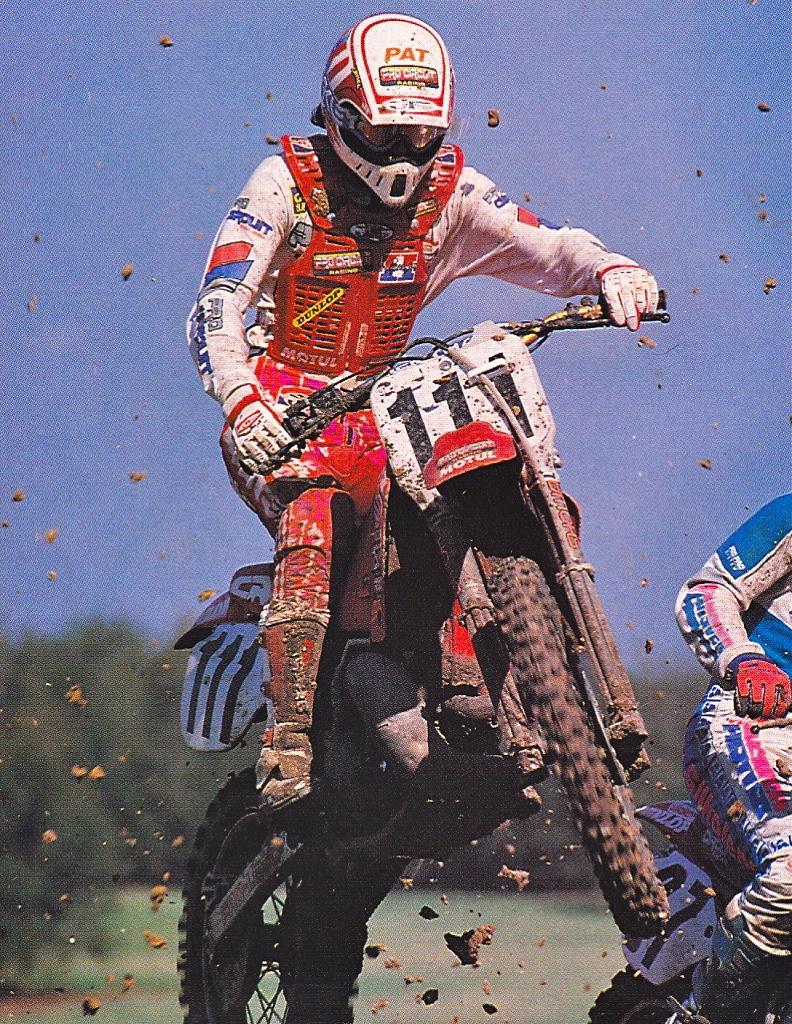

When Jean-Michel Bayle came to the US to race in 1989, he did it with an American license (hence the US flag on his shroud). Tensions with the French federation over his decision to move to the US caused him to renounce his French license (a decision that cost him $10,000) and campaign all of 1989 under the stars and stripes. Photo Credit: Unknown

By the time Jean-Michel Bayle made his decision to move to America in 1989, he was already a mega-star in Europe. In 1988, he had captured his first 125 World Motocross title and in 1989, he was set to back that up with a 250 crown. Many in Europe, including the French motocross federation, wanted him to stay in Europe and race, but the man they called JMB had bigger plans. Much like Brad Lackey a generation before, Bayle knew that if he was going to be the best, he had to race the best.

With Bayle still under contract in Europe for 1989, his plan was to race a few select US events, then return to Europe for the 250 World Championships. Unfortunately, however, the French motocross federation had other ideas. They actually tried to block Bayle’s move to the US and forced him to pay a $10,000 fine to be released out of his French motocross license. Undeterred, Bayle paid the fine and procured an American one. This meant that when Bayle was racing in the 250 World Championships in ‘89, he was actually doing so under an American license. By proudly displaying a US flag on his Factory Honda, JMB made it clear to the French bureaucrats where his feeling lay.

Before the start of the GP season, Bayle made the trek to the US to race the first few rounds of the 1989 AMA Supercross series. After landing on a hay bale and DNF’ing round one, JMB’s results would steadily improve throughout the first two months of the series. With a fifth at round two and a surprising second at round five, Bayle served notice that he was serious about being a title contender when he made the jump to the US full-time in 1990. If anyone still had any doubts about the fast Frenchman, they were certainly allayed when he put his Pro Circuit-backed Honda CR250R at the top of the victory podium in Gainesville to start the 250 National Motocross series. Clearly, Jean-Michel Bayle was for real.

When Jean-Michel Bayle showed up at Gainesville in 1989 on a privateer Honda and showed the Americans the back of his mullet it was a shot heard across the Atlantic. Smooth, stylish, and incredibly precise, JMB was here to win. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

When Jean-Michel Bayle showed up at Gainesville in 1989 on a privateer Honda and showed the Americans the back of his mullet it was a shot heard across the Atlantic. Smooth, stylish, and incredibly precise, JMB was here to win. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

After his Gainesville win, Bayle returned to Europe and wrapped up his first 250 World Motocross Title with ease. In the fall, he would return to the US once more, capturing the final round of the 500 series to bookend the US National season. With two US wins, a Supercross podium and a 250 World Motocross championship under his belt, JMB closed out a successful, and to many, surprising 1989 season. With Bayle set to move to the US full-time in 1990, the stage was set for the biggest Franco-American conflict since the early days of the republic.

After a full off-season of Supercross practice, JMB came into 1990 much more prepared than the year before. A second at round one proved he was going to be a legitimate threat for the title, but that momentum would quickly be squandered by a practice crash at round two. An injured elbow sidelined Bayle for two rounds, handing the World champ a significant points deficit. Reentering the series at round four, Bayle’s chances for the title looked bleak, but 1990 was a particularly volatile season. Early series points leader Damon Bradshaw crashed out while leading at round three, handing the victory to returning champ Jeff Stanton. Then, Stanton seemed to dash his title aspirations with a disappointing sixteenth at round five. With all of the front runners carding inconsistent finishes, it opened the door for Bayle to get back into the title chase.

By mid-season, Bayle was back to form, carding wins at Dallas, Pontiac, Tampa, New Jersey, and Foxborough. In the end, a crash-laden performance at Charlotte would torpedo his shot at the title. Even with missing two rounds and the twentieth place at Charlotte, Bayle ended up only missing the championship by a slim seven points. His five main event wins tied him with Bradshaw for the most in the series and set him up as one of the favorites for 1991.

The 1991 season would prove to be Bayle’s most successful in America. That season he would rewrite the record books by capturing the 250 Supercross, 250 Motocross, and 500 Motocross titles – a feat never done before or repeated since. While Bayle was dominating the series, he would, unfortunately, be greeted with a great deal of disdain by the American fans. With the US deep in Desert Storm patriotic fervor, there seemed to be little appetite for a foreign rider capturing our championships. While Bayle’s slightly introverted personality probably did not work in his favor, there can be little doubt that he was treated unfairly by the fans of the time.

After sweeping all three titles in 1991, Bayle lost much of his drive in 1992. He came to America to win, and once he had, he was ready to move on to new challenges. Even though his stay in the States was a somewhat rocky one, he did inspire a whole new generation of foreign riders to come to America in search of motocross glory. Photo Credit Jeff Ames

After his incredible 1991 season, Bayle lost interest in continuing to race in America. Part of that may have been his shabby treatment by the fans, part of it may have been his many disputes with his teammates, and part of it may have been the feeling that he had nothing more to prove. Regardless of the reasons, Bayle spent the 1992 season mostly going through the motions. After finishing out his contract, the enigmatic Frenchman returned to Europe to try his hand at a new challenge – road racing

Bayle’s three tumultuous years in the US were an important turning point for American motocross. After nearly a decade of US domination on the world stage, JMB’s success proved that Europe’s best could still compete with the Americans. He paved the way for future World Champions such as Greg Albertyn, Sebastien Tortelli, Grant Langston, Marvin Musquin, and Ken Roczen to come here and challenge America’s best. Because of riders like Jean-Michel Bayle, the world’s best riders often look to come here once they’ve proven themselves abroad. Thanks to these bold men, America continues to enjoy the deepest field of racers in the world. Our motocross series may not be a “World Championship” in name, but it is one in every other way that really matters.

Event #7: The Flying Circus Gets Organized

When Supercross made its debut in 1971 there was only one race and it was actually considered a motocross. By 1972, that number was up two events, with Mike Goodwin’s LA Coliseum Super Bowl race joining Daytona. By 1974, Goodwin and the Daytona promoters had added Houston to the series and formed the “Yamaha Superseries.” In 1974, the Yamaha Superseries was recognized by the AMA and the first official “Supercross” series was born. By 1976, the series had expanded to six total events, adding rounds at Dallas, Anaheim, and Pontiac. Unlike today, however, there was not a single promotional group organizing all of the Supercross events. At that time, it was more like the current motocross series, with individual promotors handling each event.

Predictably, this led to conflicts within the series; without a unified plan in place, there were sponsorship conflicts and often an “every man for himself” attitude amongst the series’ promotors. While the events continued to grow in popularity, the Wild West attitude of the men behind it often worked against the overall series’ best interests. As the sport entered its second decade, it became apparent that if Supercross was going to make the jump into a major mainstream sport, it would have to get organized.

Throughout most of the sport’s first two decades, the Supercross series was far less unified than it is today. In those days, the series was made up of a group of independent promoters each handling their own piece of the pie. This Texas race from the mid-seventies was promoted by Pace, the same company that would eventually unify the series in the nineties.

For the first twenty years of the series, Supercross was divided into three regions, plus an independent Daytona event. Mike Goodwin handled the West, Pace Motorsports the central rounds, and Jerry West’s Super Sports group the East. Each promoter secured their own event sponsors and used their own track builders. Even though Goodwin’s events proved popular, they were often money losers. It was not unheard of for Goodwin to lose over $100,000 on one night of racing. ln 1984, Goodwin sought the help of long-time off-road promotor Mickey Thompson. Thompson’s Mickey Thompson Entertainment Group (MTEG) had a proven track record of organizing successful off-road races and the pairing seemed like a good one. Unfortunately, however, this pairing would have a tragic outcome. After a few of their joint events went south, their relationship would devolve into a series of lawsuits. Thompson would win the legal battle but lose his life in a complex murder scheme hatched by Goodwin.

The murder of Thompson and his wife Judy rocked the industry in 1988 and left MTEG in the hands of their son Danny. After the murders, Goodwin left the country (it would take almost twenty years for Goodwin to finally be convicted of masterminding the crime) and MTEG continued to promote the Western Supercross events. This arrangement would last until 1995, when financial troubles at MTEG would allow Pace Motorsports (now merged with SRO Motorsports to form SRO/Pace) to acquire the rights to the western rounds.

The final consolidation of the series would occur when Super Sports agreed to turn over control of their events to SRO/Pace. With this move, SRO/Pace controlled every round of the series with the exception of Daytona. Now with a unified vision for the first time, Supercross could finally get all of its many parts moving in the same direction.

Track designs have changed greatly over the course of the last 40 years of Supercross racing. Originally the tracks were smooth and extremely fast with very few jumps. Over the years they have evolved to the point where riders spend nearly as much time in the air as on the ground. Photo Credit: USA Today

Over the next few years, Supercross would change hands several times as SRO/Pace was acquired by SFX Entertainment Inc, and later Clear Channel Communications. The Clear Channel acquisition totaled over 4.4 billion dollars in assets including hundreds of radio stations and countless live entertainment properties.

In 2005, Clear Channel decided to spin off several parts of the company (including its motorsports division) as Live Nation. Solid racing and excellent fan attendance would mark the Live Nation era. Improvements in safety like consistent track design, Tuff Blocks, and the Asterisk Mobil Medical Unit would all make their debut during this era. Overall, the Live Nation era would prove one of the most successful for Supercross. In spite of a rather nasty dust-up with AMA Pro Racing and a confusing dual championship we will cover later, the sport continued to grow throughout the 2000s.

The final chapter in this Supercross odyssey would take place in 2008 when Live Nation would sell its entire motorsports division to Feld Entertainment for a reported $205 million. Amazingly, through all the political wrangling and ownership squabbles the sport has continued to thrive. Since being consolidated by SRO/Pace, Supercross has steadily improved in both exposure and presentation. The inclusions of things like fireworks, well-produced rider introductions, and better track signage have all improved the presentation of the sport. More importantly, the involvement of major entertainment entities like Clear Channel and Feld has allowed the sport to reach a much broader audience. When the nineties started, Supercross could only be seen at three in the morning, two full months after the event took place. By the start of the 2000s, you could see most events the day after they took place, and on some rare occasions, even live through Pay-Per-View. Today, you can watch every event live on the internet and most live on TV. That is real progress that will only benefit the sport moving forward.

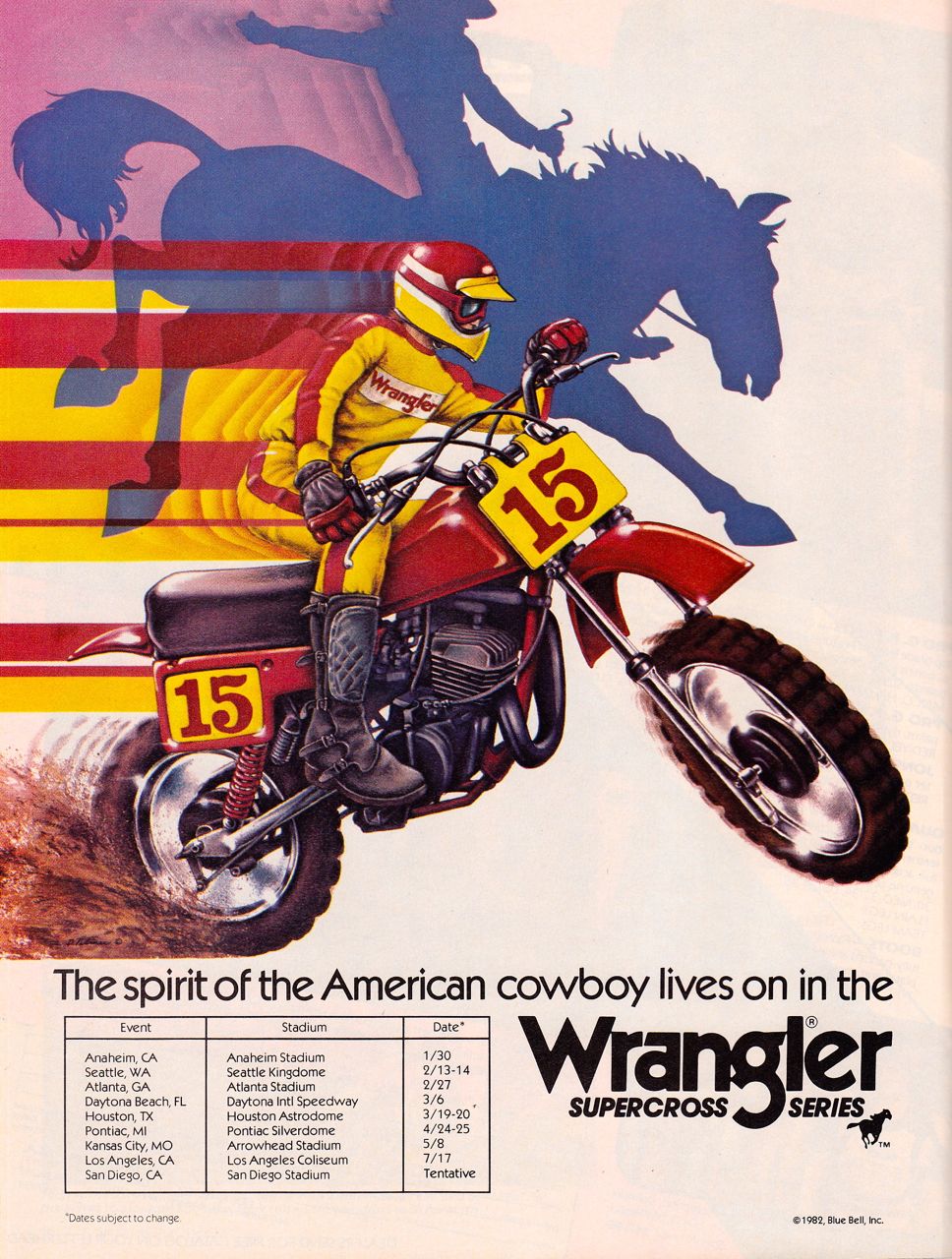

One of Supercross series’ largest partners in the early eighties was Wrangler. Like Coors, Camel, EA Sports, and a dozen others, the Wrangle connection only lasted a few brief years.

The consolidation of Supercross brought with it better sponsorship, increased exposure and greater rider safety. Certainly, not all the ideas (The SMP Jump team comes to mind) worked out as planned and some things still need improvement. Personally, I think we need to bring back the Semi races (more exposure for the second-level teams and riders), find a way to increase rider payouts, rethink these draconian drug penalties, and give the racers more of a voice in track design and safety. Overall, however, you have to admit that we are very lucky to hold the series that is the envy of the world. Feld and their predecessors helped take Supercross from a circus sideshow to the most-exciting and well-respected series in the world. For that, we should all be very thankful.

Event # 8 The Four-Stroke Revolution

Is there any more heated subject in the bench-racing world than the two-stroke vs. four-stroke debate? Even now, fifteen years after the sport went all-thumper people still decry the loss of smokers. Regardless of what side of the debate you fall on, you have to admit that the change to four-strokes has had a significant effect on the sport we love. For better or worse, everything from track design to the affordability of racing has been affected by the migration to thumpers. In reality, the switch to the four-strokes is probably the single most significant change the sport has seen in the last fifty years.

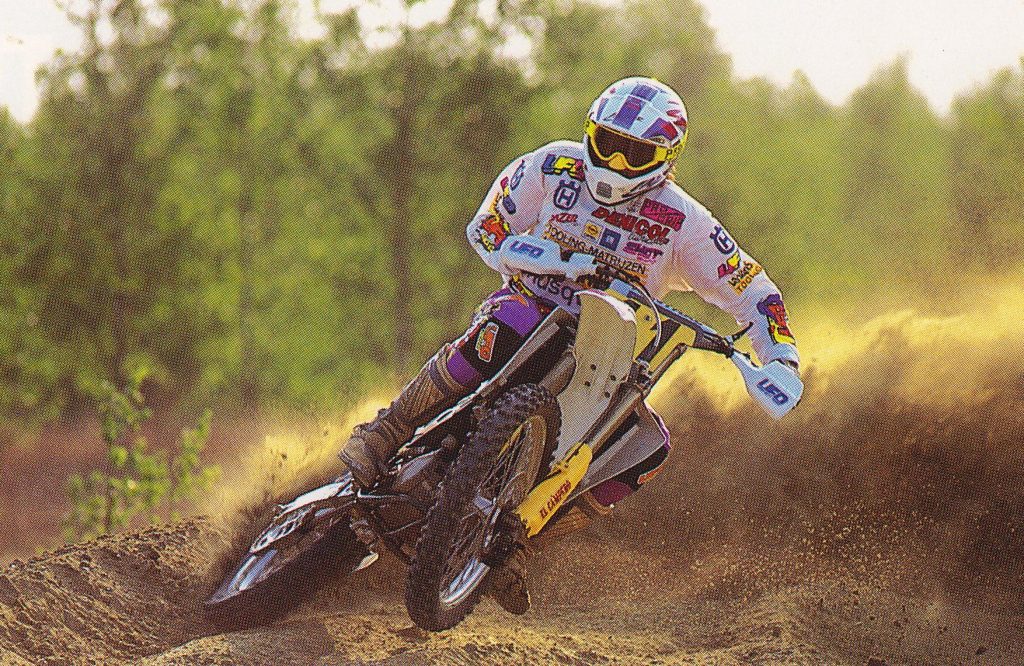

When GP veteran Jacky Martens won the 1993 500 World Motocross Title on a four-stroke Husqvarna it was seen by many as an example of how far the once-prestigious class had fallen. Few people at the time could have predicted just how prophetic his title would actually be. Photo Credit: Luc Verbeke

The modern four-stroke renaissance actually started in Europe in the early nineties. While we were still riding oil-burners on this side of the pond, the 500 class in Europe was quickly going valve-and-cam. In 1992 Belgium’s Jacky Martens made the bold decision to race a Husqvarna 610 thumper in the 500 Grand Prix. At the time, four-strokes were still considered a bit of a joke and not many people took the long-time GP veteran seriously. Martens’ first year on the big thumper was less than spectacular, but the following season he shocked many by capturing his first 500 title on the booming Husky thumper.

As the first rider to win a World Motocross title on a four-stroke since the mid-sixties, Martens’ victory was quite an accomplishment, but by this time, two-stroke development had all but stopped in the 500 class. Both Kawasaki and Honda still made them, but they were several-year-old designs with no outlook for any significant further improvements. With the Japanese abandoning the Open class, the door was opened for several smaller firms to fill that void. Companies like Vertemati, Husqvarna, and Husaberg saw that there was a niche available to manufacturers willing to pour time and money into developing a competitive big-bore thumper.

After Martens’ breakthrough, the 500 World Motocross championships would quickly become a four-stroke dominated series. Aside from Marcus Hannson on a CR500R in 1994 and Shane King on a KTM 360 in 1996, the 500 class was ruled by the big four-strokes. Fellow Belgian Joël Smets would emerge as the king of the thumpers during the nineties, earning several 500 World titles for Husaberg and KTM during the decade.

The success of the four-strokes in Europe initially had little effect on the racing here in the US. After 1993, the 500 class was retired and most people looked at the thumper conversion over there as another sign that Europe was out of touch with where the sport was heading. Bikes like the Husaberg were exotic and fast, but also heavy, finicky and often fragile. To most Americans, they were bikes for people who craved being different, not for serious racers. At the 1995 Motocross des Nations, Jeff Emig even famously commented that there was no way he was going to let Smets beat him on a big trail bike. Over here, four-strokes were for XR loonies and rich vet riders, not hard-core racers.

.

The thump heard round the world: Winning in Europe was one thing, but when Doug Henry took a four-stroke to victory at Las Vegas in 1997 the motocross community finally noticed that the winds of change were moving. Photo Credit: Donn Maeda

The first rider to really make a splash on the AMA circuit with a four-stroke was Lance Smail. The Washington native rode a massive KTM 540 thumper in the 1997 Supercross series and became the first rider to make the main event on a four-stroke at Daytona. Smail’s KTM was little more than a highly-modified trail bike and was much heavier than any of the 250 two-strokes he was competing against. While Smail’s rides on the big KTM were popular with the fans, it did little to move the racing populace toward four-stokes. Once again, it would take the Japanese to turn a promising idea into a game-changing reality.

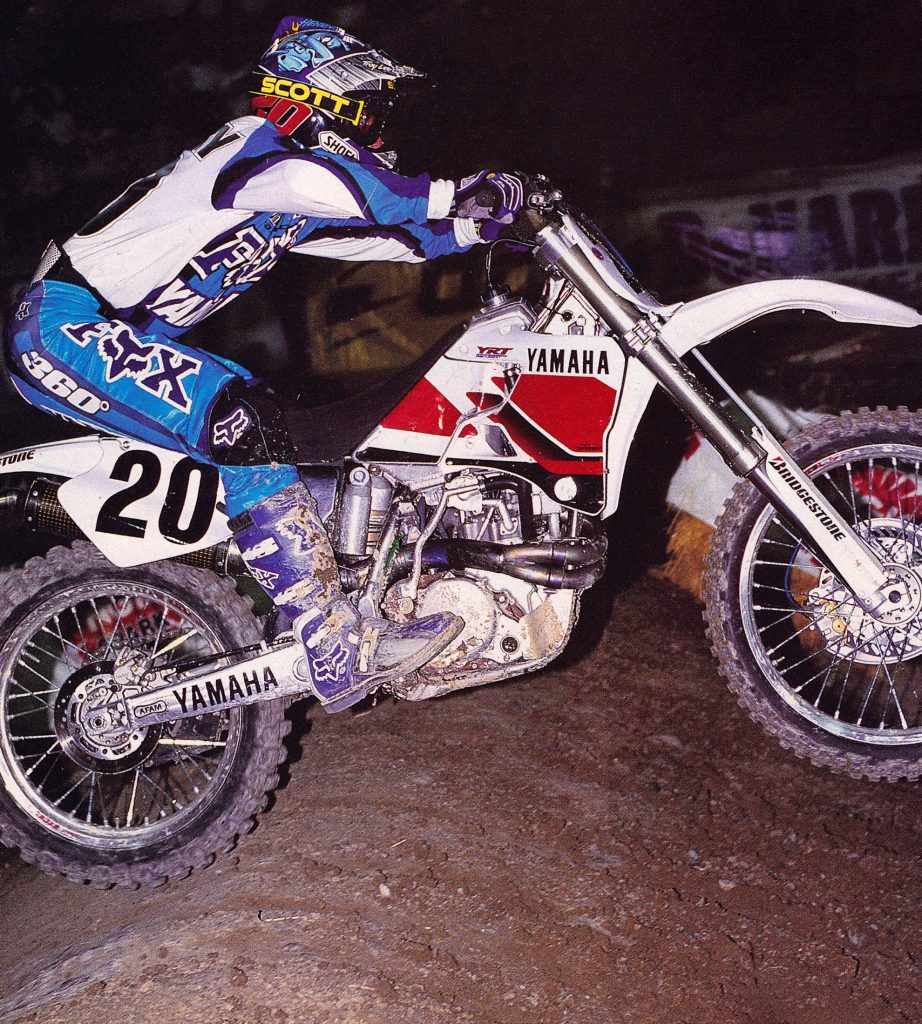

The 1997 Las Vegas Supercross was chosen as the location to debut of one of the most significant machines in motocross history, the Yamaha YZM400F. Ridden by Doug Henry, the YZM was easily the most exotic machine seen in AMA racing since the implementation of the Production Rule (Yamaha was given a one-year exemption to develop the new bike). Unlike every other “factory” bike in the field that night, the YZM was 100% works, with virtually nothing shared with between it and any other production Yamahas. As amazing as the bike was on its own if it had performed poorly it would have been little more than a curiosity that night. What Henry did though was make history by piloting the YZM400F to victory in its first try. An amazing feat on any newly-developed machine and doubly so on one so radically different than the status quo.

This works Yamaha YZM400F ridden by Doug Henry in 1997 was easily the most exotic machine raced in America since the heyday of the works bikes in the early eighties. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

This works Yamaha YZM400F ridden by Doug Henry in 1997 was easily the most exotic machine raced in America since the heyday of the works bikes in the early eighties. Photo Credit: Naoyuki Shibata

The excitement generated by the YZM400F turned out to be nothing compared to the outright fervor that accompanied the announcement that Yamaha was going to release a production version in 1998. The production version would not share much in the way of actual components with the YZM, but it would get the works bike’s high-revving short-stroke motor design. With a five-valve head derived from their road-racing program and true motocross-level componentry, the new YZ400F promised to be a very different type of four-stroke from Japan.

Upon its release, it became very apparent that Yamaha had a massive hit on their hands. The YZ400F took the enthusiast press by storm and overnight the rumble of four-strokes could be heard at tracks all across the country (much to the consternation of the track’s neighbors). Riders who had been afraid to deal with the quirks and oddball nature of ATKs, VORs, and Husabergs were more than happy to plunk down their hard-earned cash on a Yamaha.

Incredibly, the release of the YZ400F took the rest of the Japanese competition completely by surprise. None of them had anything even remotely in development at the time of the Y400F’s debut and it would take all of them several years to catch up. Honda would not have a competitor ready until 2002, with Kawasaki and Suzuki following a few years after that. KTM was faster to react, acquiring Husaberg and using their know-how to fast-track a line of all-new four-stroke machines based on their unique motor layout.

While the 1998 Yamaha YZ400F was far from perfect, it was exponentially better than any other four-strokes available at the time. Fast, refined, and stone reliable, the YZ400F helped turn a generation into four-stroke enthusiasts. Photo Credit: Yamaha

It would take nearly a decade and an absurd displacement advantage for the four-strokes to finally take over motocross. In 2006, all the major teams finally made the switch to the valve-and-cam machines full time. This effectively ended the run of the two-stroke on the professional level. Thankfully, brands like KTM, Husqvarna, and Yamaha have continued to support the two-stroke, but its days as an effective motocross weapon above the mini class are probably in the past.

Initially, the motorcycle manufacturers enjoyed a windfall from the transition to four-strokes. They were additive to their existing two-stroke business and hugely popular. As time has gone, however, those advantages seemed less sustainable. The bikes are more advanced and more powerful than ever, but also far more costly. In 2005, a new Yamaha YZ250 cost $6099. Adjusted for inflation that is roughly $7900 in 2020 dollars. That is significantly less than the $9399 a 2020 YZ450F will set you back to go racing today. Of course, that is also before you spend $1000 on an exhaust and $3000 in motor mods. Any way you look it, four-strokes have made racing more expensive.

Love them or hate them, four-strokes are here to stay. Unless there is a major breakthrough in two-stroke design, the days of the smoker in AMA pro racing have passed. They are still fun, light, fast, and affordable, and maybe that is enough. As long as at least a few of the manufacturers support them, they will be a viable option for casual riders and those on a budget. For now, at least, it’s a four-stroke world and whether that will end up being a blessing or a curse in the long run has yet to be determined.

Event #9 AMA Pro Racing Gets In A Jam

When the average rider thinks of the AMA a few things probably come to mind: 1. a stupid magazine that covers 99% Gold Wings and 1% motocross; 2. an inept organization that can’t seem to get anything done except assure the rights of idiots on Harleys to not wear helmets, and 3. a sanctioning body that thought it was a good idea to name the premier classes in the sport “Motocross” and “Supercross” (don’t even get me going on the asinine “Lites” name). In short, the AMA is thought of mostly as a bunch of bumbling incompetents that can’t even enforce their own rules. In truth, it is probably worse than that.

In 2001, a rift between Clear Channel Communications and AMA Pro Racing nearly spelled doom for the sport of Supercross as we know it. The two entities could not come to terms over a new contract and plans were made to hold two competing Supercross series. In the end, a compromise would be met, but the consequences of the split would have far-reaching effects for years to come.

In 2001, a rift between Clear Channel Communications and AMA Pro Racing nearly spelled doom for the sport of Supercross as we know it. The two entities could not come to terms over a new contract and plans were made to hold two competing Supercross series. In the end, a compromise would be met, but the consequences of the split would have far-reaching effects for years to come.

In motorsports, there are basically two groups running the events we watch; the sanctioning bodies (AMA, FIM) and the promoters (Dorna, Feld, Pace, etc.). These two groups each have separate functions and are supposed to work together to produce the races we enjoy. In the case of the sanctioning body, their responsibility is to look out for the integrity of the sport, write the rules, enforce said rules, and ensure the welfare of the riders. On the promoter side, they handle all the logistics that go into putting on the show. They secure the venue, build the track, obtain the sponsors, handle the advertising and produce the show. Usually, this arrangement runs smoothly, with each group tending to their own share of the responsibilities. Occasionally, though, the money, prestige, and egos involved can lead to an impasse between the powers that be. When this happens, the sport is never the beneficiary.

Over the years, there have been quite a few of these dust-ups between the promoters and the sanctioning bodies. In 1984, Mike Goodwin and his fellow promoters got in a power struggle with the AMA and decided to organize a competing series to run against the AMA one. Goodwin formed Insport and hired long-time industry executive Gary Mathers to run it. The new Insport series encompassed all the races except the two still controlled by the AMA; Daytona and Talladega. As a result of the split, the 1984 Supercross series actually consisted of two separate series and champions. The Insport series was won by Johnny O’Mara and is considered today to be the “legitimate” series champion. Jeff Ward won the abbreviated AMA title over Honda’s David Bailey but his victory has been relegated to the status of a footnote on the ’84 season. Eventually, cooler heads prevailed and the series moved back under AMA control.

In 1988, we had another potential series Armageddon when Mike Goodwin’s legal wrangles with MTEG led to another split series. When the first round of the 1988 series went off at Anaheim stadium it was not even considered an official “Supercross” and none of the points earned counted toward the AMA championship. Instead, Goodwin set up a three-race series he called the Triple Crown of Stadium Motocross consisting of Anaheim, San Diego, and Los Angeles. After Goodwin’s court battle ended in Thompson’s favor, things became even more heated between the parties, eventually culminating in Thompson and his wife’s murder on March 16, 1988.

When Broc Glover claimed victory on June 18, 1988, at the LA Coliseum he put an end to the most heated, controversial, and tragic season in Supercross history. Photo Credit: Kinney Jones

After the murders, a black cloud was cast over the remainder of the series. There was a great deal of mystery surrounding the crime, with most arrows pointing to Goodwin. Claiming he had received death threats, Goodwin went into hiding, leaving the situation at his now-bankrupt Stadium Motorsports Corp in limbo. Eventually, the final round of the 1988 Triple Crown in the LA Coliseum was declared a memorial race in honor of the Thompsons and folded back into the AMA series, ending the most tumultuous year in Supercross history.

In 1993, another series disaster loomed when the promoters once again found themselves at odds with the AMA. As in nearly all conflicts, the origin of this one was money. In the early nineties, the AMA took the bold move of starting its own for-profit marketing and promotional arm. Traditionally a non-profit organization, the AMA has always sold itself as an entity looking out for the wellbeing of riders and the health of the sport. When the AMA formed Paradama (the name of its for-profit arm), however, that put it in direct conflict with the promoters.

Through Paradama, the AMA was making plans to set up their own TV deal, sell series sponsorships, and eventually, promote races…all clear infringements on the fragile alliance the two groups had enjoyed over the history of the series. Enraged with this development, the promoters struck back with a plan of their own. SRO Motorsports, Pace Motorsports, and MTEG lured the AMA’s own Director of Competition Roy Jansen away from the AMA and threatened to form their own sanctioning body to oversee the races. The new American/International Racing (AIR) would replace the AMA and serve as the overseer of the new series.

Once the promoters made it clear that they were serious about going through with this move, things got heated in the AMA’s Ohio offices. Due to complicated entanglements between the AMA and the Japanese OEMs, the AMA could have forced every team but Yamaha to sit out an AIR-series. Only Yamaha, which had ceded its AMA board seat in the early eighties over another turf squabble was free to race whenever and wherever they wanted. Honda, Kawasaki, and Suzuki, on the other hand, held seats on the AMA board and were bound by a fiduciary responsibility not to harm the AMA. This left the promoters in a bind, and when the Japanese OEMs pledged to race only in an AMA series SRO Motorsports, Pace Motorsports and MTEG were forced to back down. While the AMA won the first round of this battle, the war was far from over.

Can you imagine if Chad Reed and Team Yamaha had raced in one Supercross series and Ricky Carmichael and Factory Honda had been forced to race in another? In 2003 it almost happened. Garth Milan Photo

In 2001, tensions once more ramped up as the AMA sat down to negotiate a new long-term contract with then Supercross promoter Clear Channel. Paradama (now known as AMA Pro Racing) wanted to renegotiate the profit sharing, sanctioning fees, and sponsorship rights for the series. Predictably, the series promoters met this with ire and refused to cede any control over the profit-generating side of the operation. As the negotiations ground to a halt, the AMA made it clear that if an agreement could not be reached they would break off from Clear Channel and hold their own Supercross series. While this was an inversion of previous threats, the results would have been just as dire for the health of the sport.

After it became clear that Clear Channel was not going to acquiesce to their demands, the AMA turned to one of Clear Channel’s concert promotion competitors to promote the series. Jam Sports Entertainment was contracted to line up the venues and handle the logistics of the new series. Since Clear Channel already had many of the existing stadiums locked into long-term deals, Jam Sports had to go into new markets (this was the only thing I actually liked about the new deal as the new series was set to come back to DC for the first time in 20 years) to hold its races. For 2003, Jam Sports and the AMA announced a completely new schedule that was set to run concurrently with the existing Clear Channel series. With the two parties no longer talking, it looked like 2003 might finally bring the series Apocalypse we had always feared.

The real loser in the whole Clear Channel/AMA dust-up was entertainment promoter Jam Sports Entertainment. They got drug into the mess by the AMA only to be left at the alter when Clear Channel and the AMA reconciled.

The real loser in the whole Clear Channel/AMA dust-up was entertainment promoter Jam Sports Entertainment. They got drug into the mess by the AMA only to be left at the alter when Clear Channel and the AMA reconciled.

For its part, Clear Channel was not ready to throw away the millions it had invested in Supercross so easily. Even though they were not involved in the previous promotional squabbles, they were keenly aware of the leverage the AMA held over the OEMs. This time, however, Clear Channel held an ace in the hole.

For Clear Channel, that ace was none other than the FIM. As the overarching sanctioning body for motorcycle racing all over the globe (and the parent of the AMA), the FIM sanction instantly legitimized any potential Clear Channel series. This meant all of the OEMs could race in the new FIM-sanctioned series without violating their existing agreements with the AMA. This was a huge blow to the AMA’s Jam Sport series and a virtual checkmate in the AMA’s battle for control of Supercross.

Once the FIM became involved the AMA knew that they were beaten. Behind the scenes, Clear Channel reopened negotiations with the AMA and when Jam Sports missed a scheduled deadline in late 2001 the two reconciled. This left Jam Sports holding the bag for the whole fiasco. Eventually, Jam Sports would sue Clear Channel, claiming the promoter had violated the terms of their agreement with the AMA by continuing to negotiate with them after Jam Sports had signed a letter of intent. In 2005, the courts awarded Jam Sports a ninety-million-dollar settlement stating that Clear Channel had undermined Jam Sports’ agreement with the AMA and conspired to prevent them from acquiring venues for the purposed series.

For 2003, it was decided that there would be two separate but intertwined championships run. The new “World Supercross GP” would start in December of 2002 in Geneva, Switzerland and then move to Arnhem, Holland, before rejoining our series at Anaheim in January of 2003. In order to qualify for the new World Supercross GP title riders would need to participate in both of the European rounds. This was designed to pressure the US teams into racing these two overseas events, but only Yamaha and KTM made the trip. While these events are largely forgotten to history, they will always be known as the only races run by seven-time Supercross Champion Jeremy McGrath on his new factory KTM. After struggling on the new machine, McGrath announced his official retirement from racing at the first US round in January.

While the World Supercross GP is largely forgotten today, its one footnote to history is Jeremy McGrath’s appearance in the first two European rounds of the 2003 series. After struggling on his new KTM in Europe, the King would announce his retirement at the first round of the US series. Photo Credit: Transworld MX

In due course, these European rounds were moved to Canada and eventually, discontinued altogether. While the World Supercross GP turned out to be another flop, the other effects of the FIM’s involvement in the AMA series have proven far longer lasting. With the inclusion of the FIM into our series, Supercross had to move to the rules and regulations that governed racing in Europe. That meant all-new standards for fuel at a time when two-strokes were quickly coming under fire from the new four-strokes. The FIM-mandated unleaded fuel requirements had little or no effect on the thumpers, but it made it much harder to tune the two-strokes. Bikes that previously ran perfectly now constantly fouled plugs and refused to clean out properly. Within three years of the move to unleaded fuel, the two-strokes would be gone from Supercross entirely.

After the Jam Sports fiasco, an ugly lawsuit with road racing promoter Roger Edmondson, and several high profile missteps involving fuel penalties, the AMA would finally make the decision to move away from the for-profit side of their business. In 2008, the AMA entered into an agreement in principle to sell the sanctioning, promotional and management rights for its AMA Pro Racing properties to the Daytona Motorsports Group (DMG). This meant the AMA Motocross Series, the AMA Flat Track Series, the AMA Supermoto Series, the AMA Hillclimb Series, and ATV Pro Racing were all no longer under AMA control. After this move, only the AMA Supercross and Arenacross series were still under AMA sanction (due to the previously-signed agreement with Clear Channel). Even though the AMA ceded much of its authority, the agreement allowed the DMG to continue to use the AMA name through a licensing agreement between the two.

While the formation of the World Supercross GP offered the manufactures another shot at a title each season, its prestige never rose above that of its earlier incarnations. Photo Credit: Yamaha.