For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Honda’s all-new 1991 CR125R.

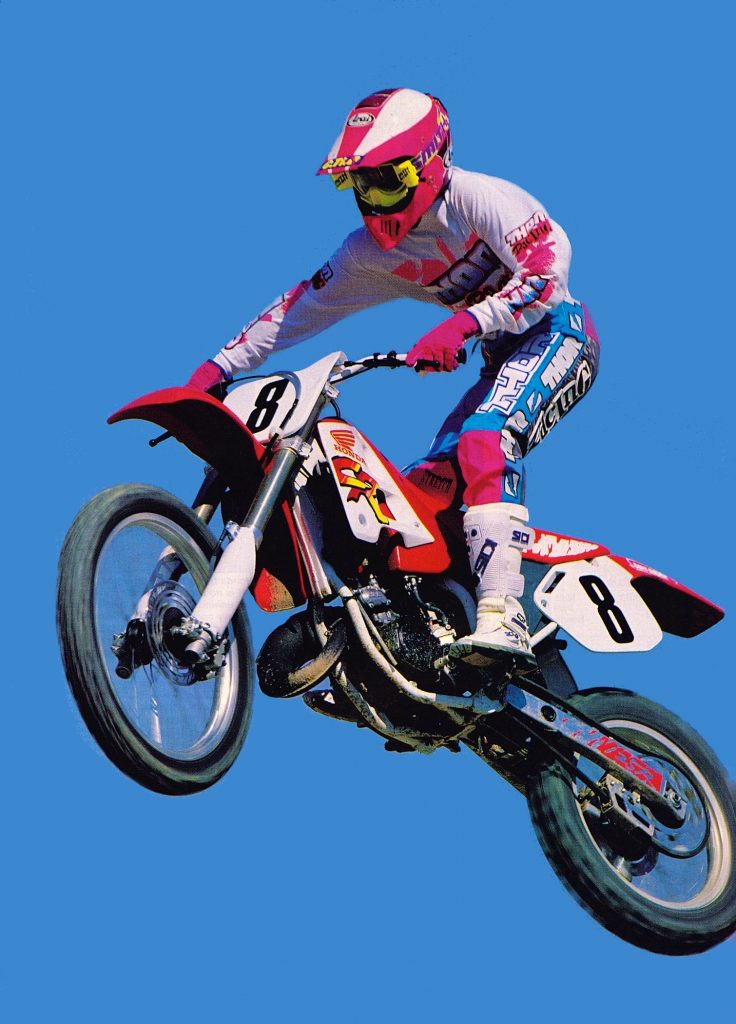

Bold styling, updated suspension, and an all-new chassis highlighted the CR125R package for 1991. Photo Credit: Honda

Bold styling, updated suspension, and an all-new chassis highlighted the CR125R package for 1991. Photo Credit: Honda

The late eighties and early nineties were a great time to be riding red in the 125 class. For a solid decade, the winged machines enjoyed a power advantage over their rivals that was nearly unassailable. Year in and year out, the CR125Rs put it to their competition with their blistering motor performance. Not always the best suspended or best handling machines in the class, the CRs of this era dominated through horsepower rather than handling finesse. For fast locals and aspiring pros alike, this horsepower advantage was an allure that was all but impossible to resist.

An all-new chassis for 1991 shortened the CR’s wheelbase and tightened up its steering geometry significantly. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new chassis for 1991 shortened the CR’s wheelbase and tightened up its steering geometry significantly. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1990, this formula had once again played out in the 125 class as Honda’s blisteringly fast CR125R took on a loaded class of eighth-liter contenders. That season, the big news had been Kawasaki’s all-new KX125, which broke major new ground in chassis design with its revolutionary perimeter frame. The KX looked like a machine from the future and actually tried to beat Honda at their own game by producing a mid-and-up powerband that was catered to pros rather than embracing the masses. With its radical looks, innovative chassis, and newfound horsepower, the KX125 had proved incredibly popular with buyers and magazine editors alike.

In addition to the new frame, the 1991 CR125R also adopted the 1990 CR250R’s redesigned bodywork. This cleaned up the styling and offered a flatter pilot compartment for improved rider movement. Photo Credit: Honda

In addition to the new frame, the 1991 CR125R also adopted the 1990 CR250R’s redesigned bodywork. This cleaned up the styling and offered a flatter pilot compartment for improved rider movement. Photo Credit: Honda

While the KX was stealing the lion’s share of press in 1990, the tried-and-true CR marched into the new decade with a mild refresh that turned out to be a bit of a mixed blessing. In 1989, the red team had dialed up an all-new chassis for the CR125R that significantly improved the handling and feel of the machine. New “low boy” bodywork inherited from the ’88 CR250R gave the red tiddler an incredibly slim and comfortable layout that perfectly complemented its go-for-broke style of motor. Changes made to the settings of its 43mm Showa conventional forks and new Delta-Link shock left most non-pros scratching their heads, but for winning at the National level the ’89 CR125R was a lethally-effective package.

In 1990, the CR125R had adopted the CR250R’s Honda Power Port system in an effort to boost the torque output of the 125cc mill. While complicated and maintenance intensive, the HPP system did help give the CR125 an undeniable power advantage over its rivals. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1990, the CR125R had adopted the CR250R’s Honda Power Port system in an effort to boost the torque output of the 125cc mill. While complicated and maintenance intensive, the HPP system did help give the CR125 an undeniable power advantage over its rivals. Photo Credit: Honda

For 1990, Honda tried to address the two complaints most riders had voiced in 1989 by beefing up the torque and shelving the forks on their one-two-five racer. A redesigned motor dropped the ATAC (Automatic Torque Amplification Chamber) system in use since 1984 in favor of a version of the HPP (Honda Power Port) design found on the CR250R. This more advanced power valve design altered the size of the exhaust port rather than just changing the volume of the expansion chamber to boost torque. In addition to the new motor, the 1990 CR125R also adopted an updated version of the controversial 45mm Showa inverted forks found on the CR250R and CR500R in 1989. These forks had offered significant improvements in rigidity and steering precision but had failed to win over many fans with their harsh action.

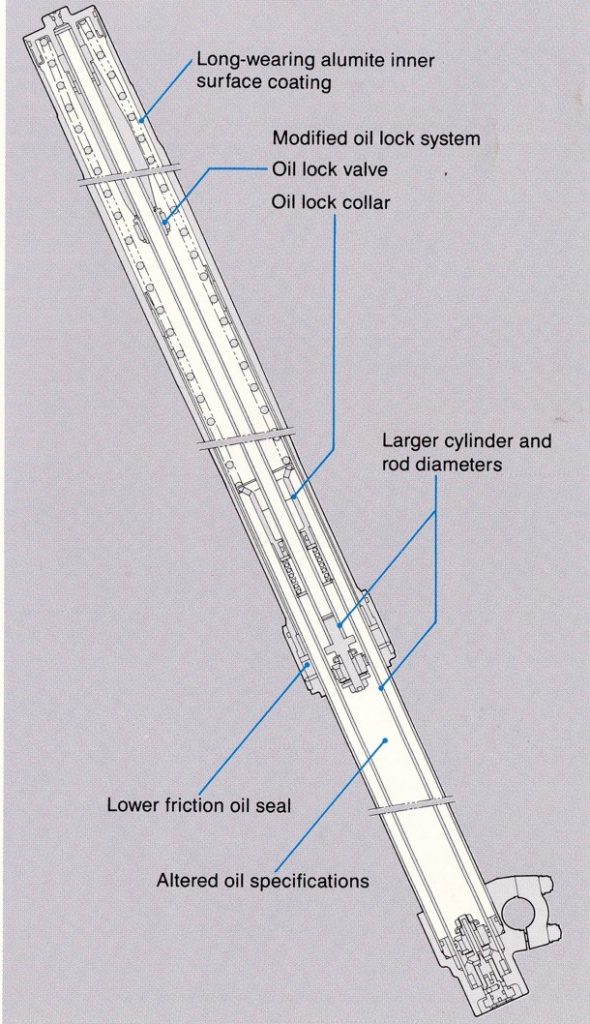

An all-new Showa inverted fork for 1991 featured a redesigned cartridge system and several updates aimed at reducing friction and increasing durability. Photo Credit: Honda

An all-new Showa inverted fork for 1991 featured a redesigned cartridge system and several updates aimed at reducing friction and increasing durability. Photo Credit: Honda

With its white frame, inverted forks, and a return to the “flash red” of the mid-eighties, the 1990 CR125R looked dramatically different than in 1989 but its performance turned out to be largely unchanged. The new HPP motor improved torque slightly but its power remained focused at the upper rev ranges of the power curve. The new forks looked trick but remained punishingly poor performers. They were prone to bottoming, incredibly harsh in action, and only got worse as small amounts of metal flaked off inside and clogged up their delicate internals. The CR’s shock was equally grim and held back an otherwise winning 125 package. Wickedly fast but demanding to ride, the CR125R remained a pro-level machine saddled with amateur hour suspension performance.

With Pro Circuit handling their 125 racing effort, there were a lot of Honda CR125Rs at the front of the pack in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

With Pro Circuit handling their 125 racing effort, there were a lot of Honda CR125Rs at the front of the pack in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

For 1991, Honda looked to broaden the appeal of the red rocket by once again completely redesigning the suspension on the CR125R. An all-new set of “spring-above-cartridge” Showa forks replaced the universally panned units of 1990 and an all-new Kayaba shock added increased adjustability and a linkage curve cribbed from the CR250R. The new forks featured the same 45mm outer diameter as 1990 but internally Honda addressed the complaints levied at the old design by increasing the spring rates, enlarging the cartridge unit, and installing a new bottoming system. The springs were also repositioned to sit on top of the cartridge units to reduce oil flow restrictions. To alleviate the oil contamination issues of 1990, Honda’s engineers also hard anodized the inner surfaces of the fork tubes and polished the outer surface of the new fork springs. This both lessened stiction within the fork and reduced the amount of aluminum sloughed off into the fluid. Travel remained unchanged from 1990 with 12 inches of movement available. Unlike most of its competitors, the CR’s new forks only offered compression damping adjustability. There were 14 selectable settings available but no external adjustment available for rebound control.

In 1991, the CR’s case-reed HPP mill produced a long and strong flow of power that took off in the middle and never stopped pulling. Low-end power was sorely lacking but once the Honda was on the pipe it had no equal. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1991, the CR’s case-reed HPP mill produced a long and strong flow of power that took off in the middle and never stopped pulling. Low-end power was sorely lacking but once the Honda was on the pipe it had no equal. Photo Credit: Honda

On the shock side, the new KYB damper featured 12.2 inches of travel and 22 selectable adjustments for compression damping. Unlike the forks, the shock did offer 20 positions for rebound adjustability. To provide smoother operation all of the link bushings and shock mountings were upgraded with Teflon coatings for 1991. According to Honda, this resulted in a substantial 50% reduction in friction throughout the rear suspension system. Both the swingarm and linkage were all-new for 1991 and featured new ratios for the Pro-Link and lighter overall weight.

With the most power and widest spread, the CR125R motor had the performance to pull you to the front in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

With the most power and widest spread, the CR125R motor had the performance to pull you to the front in 1991. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the chassis side, the 1991 CR125R featured a completely new frame that altered the machine’s layout and geometry substantially. In the mid-to-late eighties, Honda’s CR had enjoyed the sharpest handling manners in the 125 class. The red machines shook their head like a wet dog when coming down from speed but could also cut underneath anything short of a PW50. By 1990, however, a new breed of ultra-aggressive handlers from Kawasaki and Suzuki had supplanted the Honda as the king of the inside line. Super-strong frames and pulled-in rakes gave the CR’s competition newfound prowess that made the 1990 CR125 feel positively pedestrian by comparison.

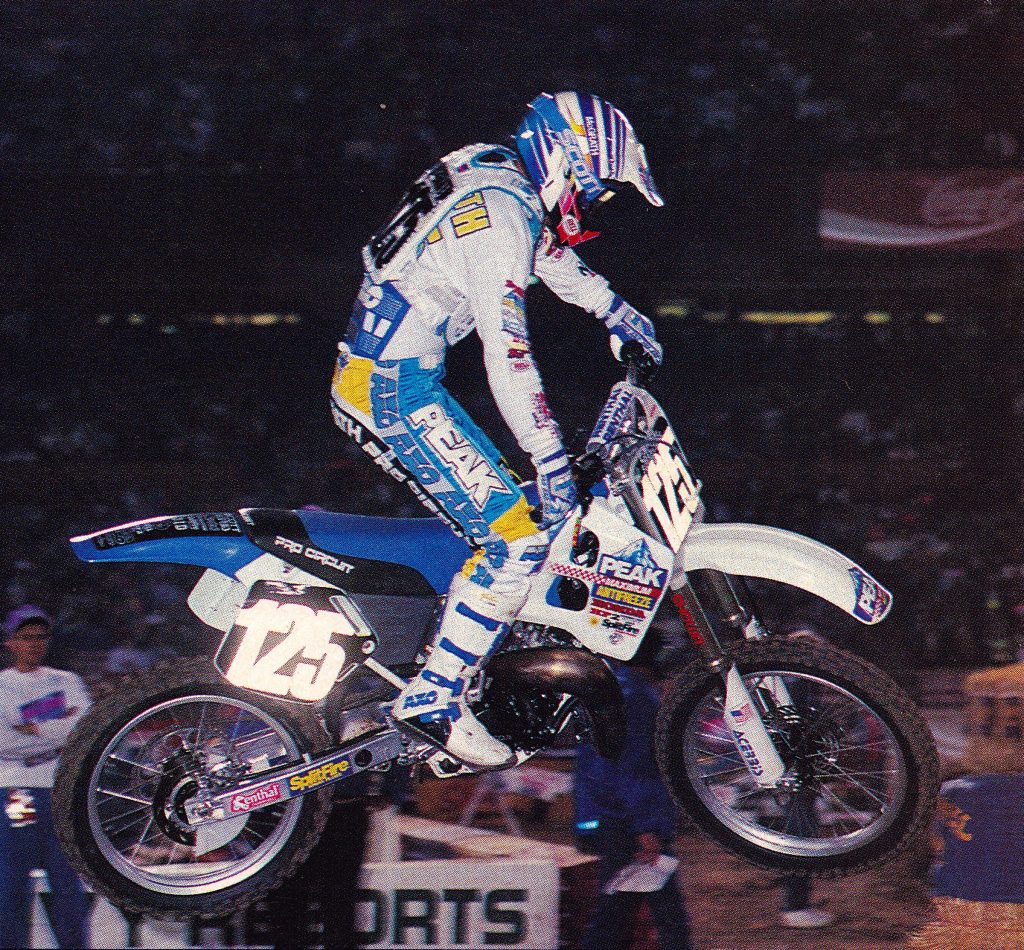

Peak Pro Circuit’s Jeremy McGrath took the all-new CR125R to the 125 West Coast Supercross title in 1991. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Peak Pro Circuit’s Jeremy McGrath took the all-new CR125R to the 125 West Coast Supercross title in 1991. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

For 1991, Honda redesigned the CR’s frame to reclaim its lost position as the king of the corners in the 125 class. This was achieved by moving the steering stem down by 2.5mm and back by 1.5mm. Both the rake and trail were also reduced and the motor was repositioned to sit 3.5mm lower in the chassis. The new tighter angles reduced the Honda’s wheelbase by nearly half an inch and placed more weight on the front wheel for improved traction in the turns.

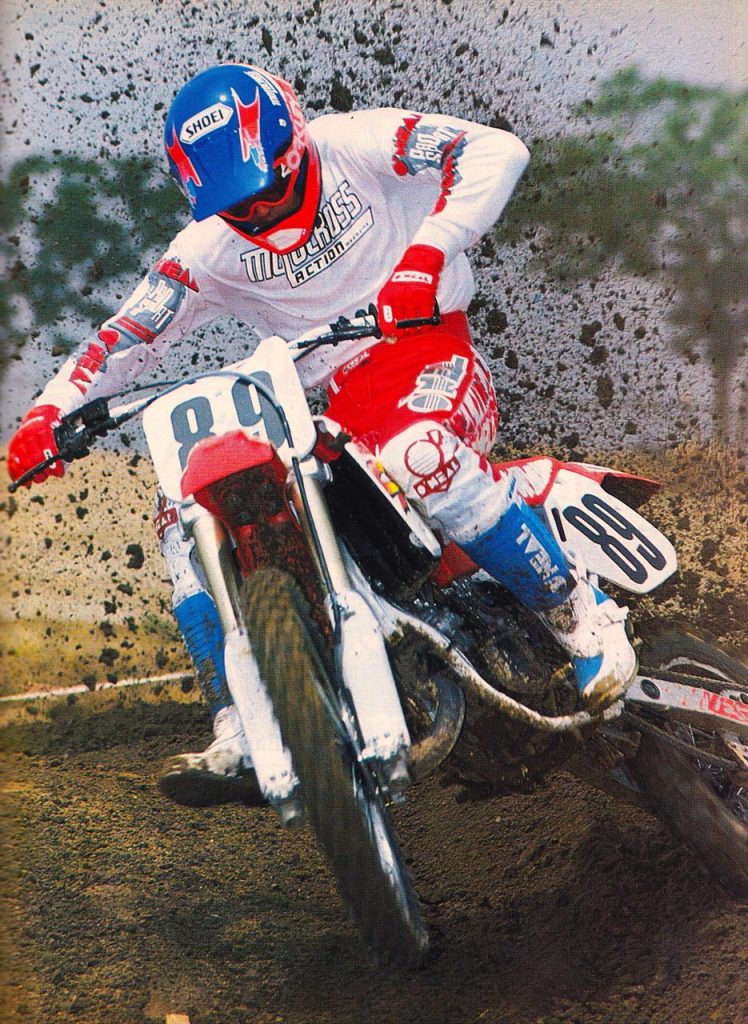

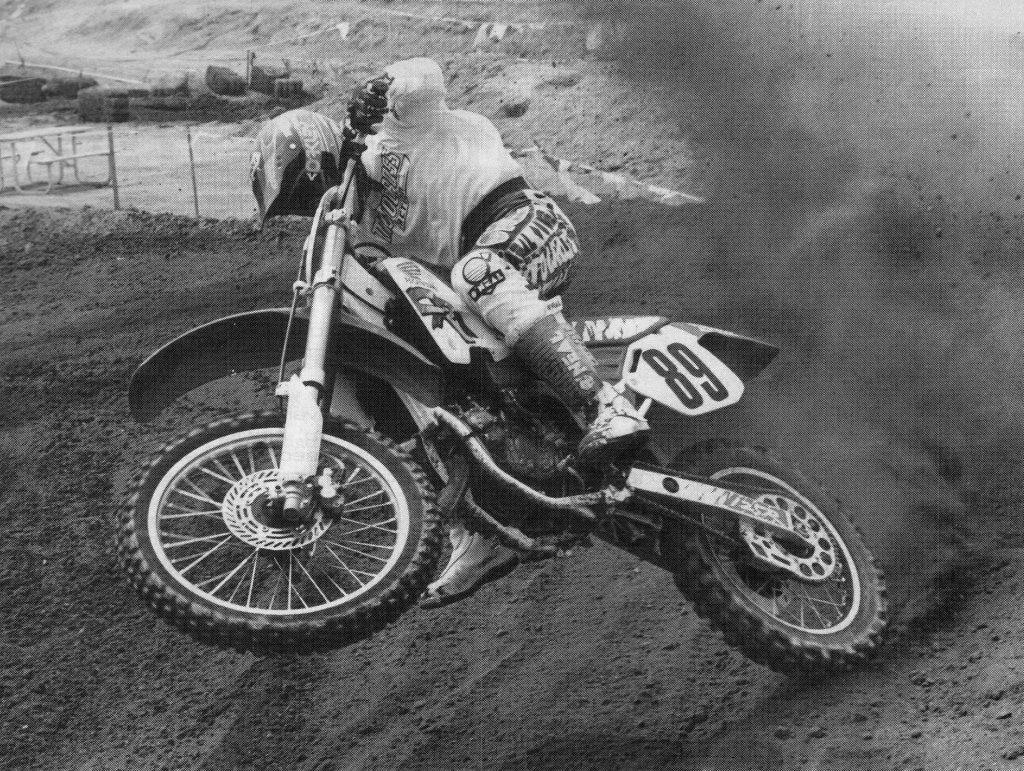

Geometry changes for 1991 yielded a sharper steering response on the CR125R. Overall handling was excellent with the only complaint being a rather nasty bit of headshake when coming down from speed. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Geometry changes for 1991 yielded a sharper steering response on the CR125R. Overall handling was excellent with the only complaint being a rather nasty bit of headshake when coming down from speed. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

Mated to the new frame was redesigned bodywork that adopted the look introduced on the CR250R in 1990. This meant a new tank, shrouds, seat, side plates, and rear fender for 1991. The airbox was all-new as well and offered a sleeker profile and improved access to the filter. The new bodywork remained some of the slimmest in the class with excellent ergonomics that fit a wide range of riders. The new seat was taller and firmer with a flatter profile that made it easier to slide fore and aft when necessary. While the new bodywork was very similar to what had been on the 250 in 1990, the switch to white for the radiator shrouds and some very bold new graphics set the ’91 machine apart from its more conservative predecessor.

While the Honda’s HPP mill offered the most peak output in the class, its relative lack of hit and soft low-end response made it a demanding motor to ride fast. Talented riders loved its long pull but slower pilots were likely to be happier once it was geared down. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

While the Honda’s HPP mill offered the most peak output in the class, its relative lack of hit and soft low-end response made it a demanding motor to ride fast. Talented riders loved its long pull but slower pilots were likely to be happier once it was geared down. Photo Credit: New England Motorcycle Museum

In the motor department, the CR125R was largely a carryover for 1991. In 1990, Honda had moved to the HPP cylinder design on the 125 and the CR had gained a bit of much-needed torque. The motor’s power curve was still pro-oriented, but it did provide a bit more flexibility for those who were either unwilling or unable to keep the throttle pinned at all times.

The 1991 Honda CR125R offered an excellent base from which to build a championship-winning racer. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The 1991 Honda CR125R offered an excellent base from which to build a championship-winning racer. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

For 1991, Honda stuck to minor changes aimed at improving performance and increasing reliability. Internally, the 125cc HPP mill featured a new crankshaft that offered upgraded bearings and an increase in the size of the connecting rod. The head was also reshaped slightly and paired with a new ignition that aimed to alleviate the annoying popping some CRs had suffered from in 1990. The carburetor was also massaged with a redesigned jet block and recontoured slide to improve sealing. When combined with the new larger airbox, all of these changes were designed to improve throttle response and punch up the CR’s rather pedestrian low-end performance.

Jackhammers: Despite a total redesign the CR125R’s new 45mm Showa forks offered familiarly grim performance. Harsh in the mid-stroke and punishing on small chop, these were the worst forks available from Japan in 1991. Photo Credit: Honda

Jackhammers: Despite a total redesign the CR125R’s new 45mm Showa forks offered familiarly grim performance. Harsh in the mid-stroke and punishing on small chop, these were the worst forks available from Japan in 1991. Photo Credit: Honda

On the track, the new CR125R turned out to be better, but not particularly different than the year before. As in 1990, the motor was soft down low and prone to bogging with the stock gearing in place. Once on the pipe, however, it pulled strongly through a broad midrange and shrieking top-end hook. Unlike the punchy KX and RM, there was not a lot of actual hit, just a long and strong flow of power that just kept on pulling and pulling. From the midrange up it was by far the fastest machine in the class but it took talent to make the most of that high-rpm power. Out of turns, it required commitment and a fair amount of clutch to clear obstacles that were a piece of cake on the much snappier RM125. For fast guys this was no issue, but slower riders were likely to be happier once they added a tooth or two to the rear sprocket. As in 1990, the Honda’s clutch and transmission were nearly flawless in operation offering class-leading durability and excellent feel. This made it easier to get the most out of Honda’s potent power package.

With a talented rider aboard the CR125R was capable of some serious berm shredding in 1991. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

With a talented rider aboard the CR125R was capable of some serious berm shredding in 1991. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the handling front, the new more aggressive CR125R offered an improved version of what Honda riders had come to expect from a CR125. That meant excellent steering response, a light feel, and a propensity to try and rip your hands from the bars when decelerating in the rough. Both the CR’s ability to turn and its penchant for headshake was increased by the chassis changes for 1991. On a tight Supercross-style track this was an acceptable tradeoff, but at Glen Helen on a Wednesday the CR could be a real handful. Dropping the forks slightly in the clamps, moving the rear wheel back as far as it would go, and cinching down the nut on the steering stem were all popular ways to mitigate this trait but it never fully went away. When compared to its rivals, the new CR was sharper in the turns than the KX and YZ and but not quite as nifty at changing direction as the ultra-quick RM. At speed, it was more planted than the slightly schizoid Suzuki but far less stable than the Yamaha and Kawasaki. Overall, it was a great Supercross handler that required a bit of attention when the speeds increased outdoors.

While the landings were not always the most comfortable, the CR125 still made an able aerial partner. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While the landings were not always the most comfortable, the CR125 still made an able aerial partner. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

As in 1990, some of the CR’s high-speed handling quirks were certainly due to its disappointing suspension performance. Despite a total redesign, the new 45mm Showa forks turned out to be only slightly better than the woeful 1990 versions. They remained harsh in the mid-stroke, skittish on the small chop, and too quick on the rebound. This only exacerbated the CR’s lack of stability as the forks struggled to follow the terrain on small sharp impacts. The new heavier springs and Simons-style bottoming system did reduce the metal-to-metal clank on big hits but the fork’s action remained the poorest of the four Japanese contenders.

The new KYB shock on the CR offered lackluster performance similar to the forks. Bottoming control was decent but its harsh ride was panned by all. Photo Credit: Honda

The new KYB shock on the CR offered lackluster performance similar to the forks. Bottoming control was decent but its harsh ride was panned by all. Photo Credit: Honda

Out back, the Kayaba shock provided a similarly rough ride. For larger and faster pilots, it provided a well-controlled ride that could be trusted not to do anything crazy in large whoops or when landing from big jumps, but at no point in its travel was it plush. Small bumps and chop flummoxed its damping and the CR could be difficult to get hooked up once the track started to deteriorate. Under acceleration, the Pro-Link transmitted a great deal of the track’s surface to the rider’s backside and even fast guys complained about its lack of low-speed comfort. While the new shock was an improvement over the year before, it remained the least-liked damper in the 1991 125 field.

Eye of the Tiger: The styling on the new CRs was a bit of an acquired taste in 1991. While certainly more conservative than the Rorschach test Suzukis, this new look still constituted a fairly radical departure for the typically conservative Honda brand. Photo Credit: Honda

Eye of the Tiger: The styling on the new CRs was a bit of an acquired taste in 1991. While certainly more conservative than the Rorschach test Suzukis, this new look still constituted a fairly radical departure for the typically conservative Honda brand. Photo Credit: Honda

On the details front, the new CR125R was one of the best machines available in 1991. On the plus side were its tough and well-fitting plastic, high-quality fasteners, and excellent switchgear. The bars, levers, grips, and controls were well-shaped and more durable than the components used by the competition. Taking the CR apart also took fewer wrenches, with the bolts and nuts being far less likely to strip or break when removed. Overall motor reliability was excellent but some CR125s still suffered from the ’90 model’s annoying popping on the top end. This did not seem to affect performance but many riders found this CR quirk irritating.

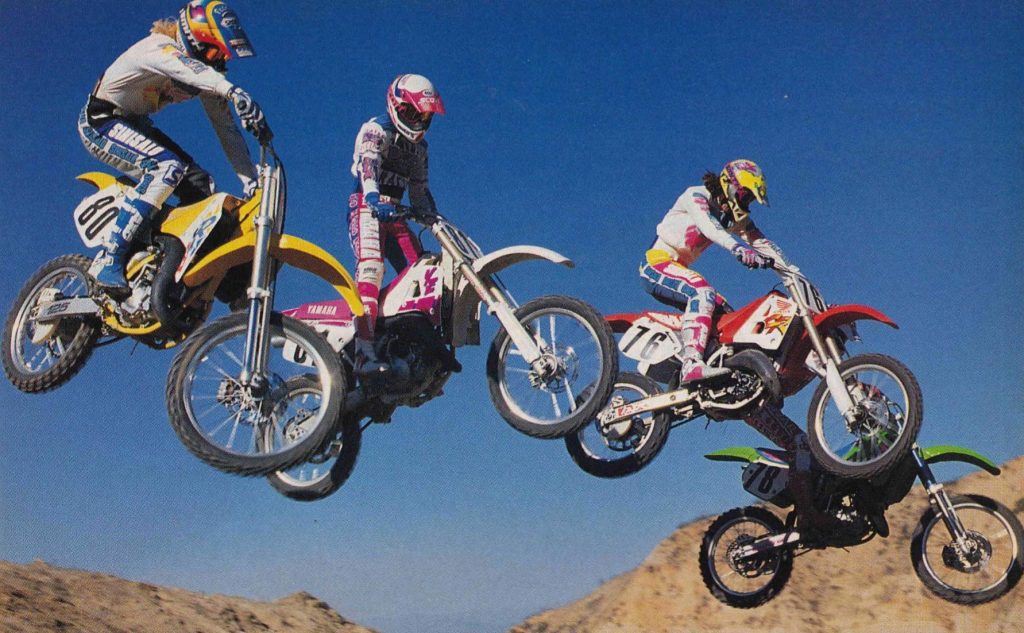

The 125 class was the most diverse and hotly contested division in motocross in 1991. Every machine offered its distinct advantages and not a single major motocross magazine picked the same shootout winner this season. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

The 125 class was the most diverse and hotly contested division in motocross in 1991. Every machine offered its distinct advantages and not a single major motocross magazine picked the same shootout winner this season. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the Honda’s clutch did not offer the lightest pull in the class, its rock-solid durability in the face of constant abuse won over many converts from the lighter-pulling but less robust Suzuki. Braking feel and power were once again the tops in the class with the CR offering excellent and trouble-free performance. The Honda’s graphics, while of somewhat questionable taste, proved durable and the bike generally looked and felt fresh far longer than most of its rivals. With its fully removable and replaceable rear subframe, the CR was also easier to service and less costly to repair in the event of a major crash than the RM and YZ, which both made do with only a single access bar to aid shock servicing.

With the skill to keep it on the pipe and the strength to make its suspension work, the 1991 CR125R could be a successful motocross companion. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

With the skill to keep it on the pipe and the strength to make its suspension work, the 1991 CR125R could be a successful motocross companion. Photo Credit: Fran Kuhn

On the demerits side for 1991 were the CR’s aforementioned popping issues, a propensity to foul plugs, pro-only stock gearing, disconcerting deceleration wobble, and subpar suspension action. The Honda Power Port system was also an utter nightmare to service and extremely easy to get out of whack. Its footpegs were also narrow in comparison to the floorboards found on the KX125, but so were everyone else’s in 1991.

Boldly styled and pro-focused, the 1991 CR125R offered the power to win for those talented enough to appreciate its virtues. Photo Credit: Honda

Boldly styled and pro-focused, the 1991 CR125R offered the power to win for those talented enough to appreciate its virtues. Photo Credit: Honda

Overall, the 1991 Honda CR125R turned out to be an updated but not necessarily more effective motocross weapon. Its motor was still blisteringly fast but its powerband was aimed squarely at pros and fast intermediates. Throttle jockeys loved its endless pull but those of lesser talent found its lack of torque and smooth power frustrating. Its suspension was also much better at blitzing supercross whoops than gobbling up choppy straights. For top-level racing, it offered an excellent base from which to build a title-winning package, but for most mere mortals there were probably better choices available in 1991.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com