For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to take a look back at Yamaha’s mid-eighties XR-fighter, the 1986 TT350.

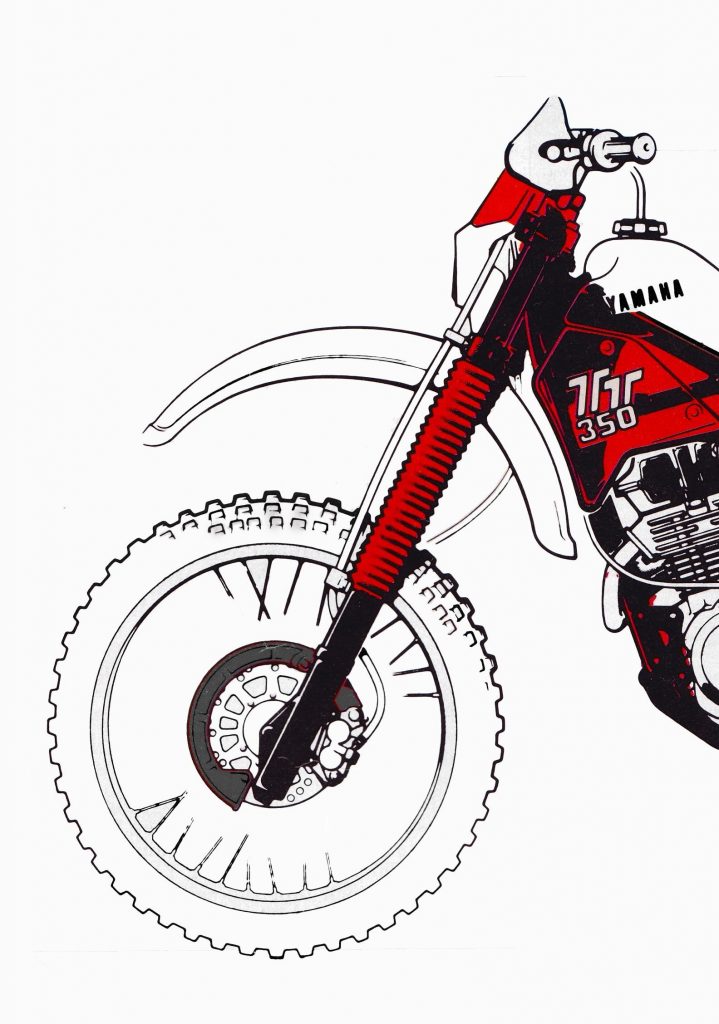

In 1986 Yamaha launched its competitor to Honda’s popular XR350R. Part YZ motocrosser and part XT dual-sport, the all-new TT350 filled the niche for a mid-size machine with big-bore potential. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1986 Yamaha launched its competitor to Honda’s popular XR350R. Part YZ motocrosser and part XT dual-sport, the all-new TT350 filled the niche for a mid-size machine with big-bore potential. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In the world of off-roading, there has always been a loyal and passionate following for the rugged and ready-for-anything four-stroke. Even after the transition to lightweight two-strokes in the 1960s, the manufacturers continued to develop and release an assortment of thumpers aimed at the off-road market. Although far heavier than their two-stroke competition, the smooth power, excellent torque, and stone-ax reliability of these valve-and-cam machines earned them a loyal following that endures to this day.

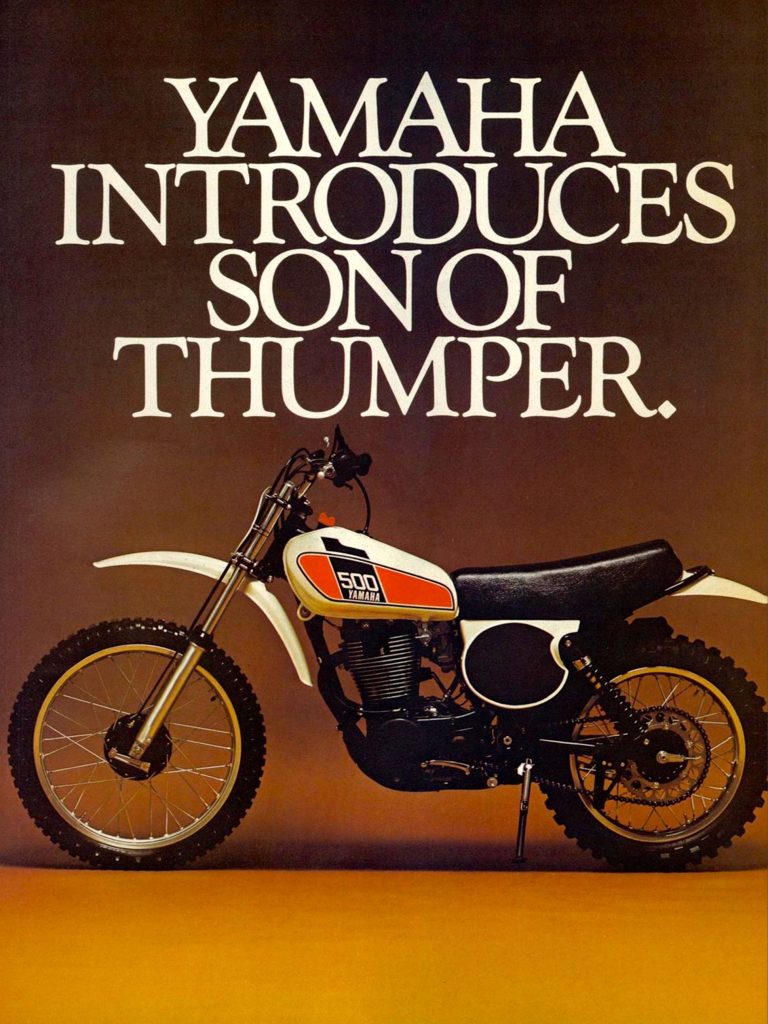

While Honda’s XR line is synonymous with the Japanese off-road four-stroke, Yamaha’s TT line actually pre-dated the full-size XRs by several years. Introduced in 1976, the mighty TT500 proved one of the most popular off-road models of the late seventies. Eventually, Yamaha’s thundering four-stroke single would make its way to several off-road racing disciplines, even winning the 1977 Luxembourg 500 Grand Prix with Bengt Åberg at the controls. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While Honda’s XR line is synonymous with the Japanese off-road four-stroke, Yamaha’s TT line actually pre-dated the full-size XRs by several years. Introduced in 1976, the mighty TT500 proved one of the most popular off-road models of the late seventies. Eventually, Yamaha’s thundering four-stroke single would make its way to several off-road racing disciplines, even winning the 1977 Luxembourg 500 Grand Prix with Bengt Åberg at the controls. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1976, Yamaha jumped into the off-road four-stroke game with an all-new big-bore thumper, the TT500. Like other four-strokes of the era, the TT was heavy and slightly cumbersome, but riders loved the gobs of torque provided by its 499cc SOHC four-stroke power plant. The TT500 proved to be an instant hit and provided the basis for all manner of Hot Rod racing thumpers in the late seventies and early eighties. During this period, modified TT500s found their way to dirt track, desert, enduro, and even motocross competition.

Sayonara: In 1986, Honda retired their successful XR350R in favor of focusing on an all-new XR250R. This left the door open for Yamaha to corner the mid-size four-stroke market with the new TT350. Photo Credit: Honda

Sayonara: In 1986, Honda retired their successful XR350R in favor of focusing on an all-new XR250R. This left the door open for Yamaha to corner the mid-size four-stroke market with the new TT350. Photo Credit: Honda

In 1979, Honda introduced a TT500 competitor in the form of the all-new XR500. Like the TT, the new XR featured a large four-stroke single wrapped in a motocross-style chassis. At the time, the big-bore XR was also joined by a 250 and 185 version that helped give Honda the widest lineup of full-size four-strokes in the off-road arena. While far from high-performance, the new XRs proved to be a huge hit for Honda. Two-stroke competitors like the Yamaha IT, Suzuki PE, and Kawasaki KDX were lighter and faster, but people continued to be drawn to the XR’s ease of use and rugged reliability.

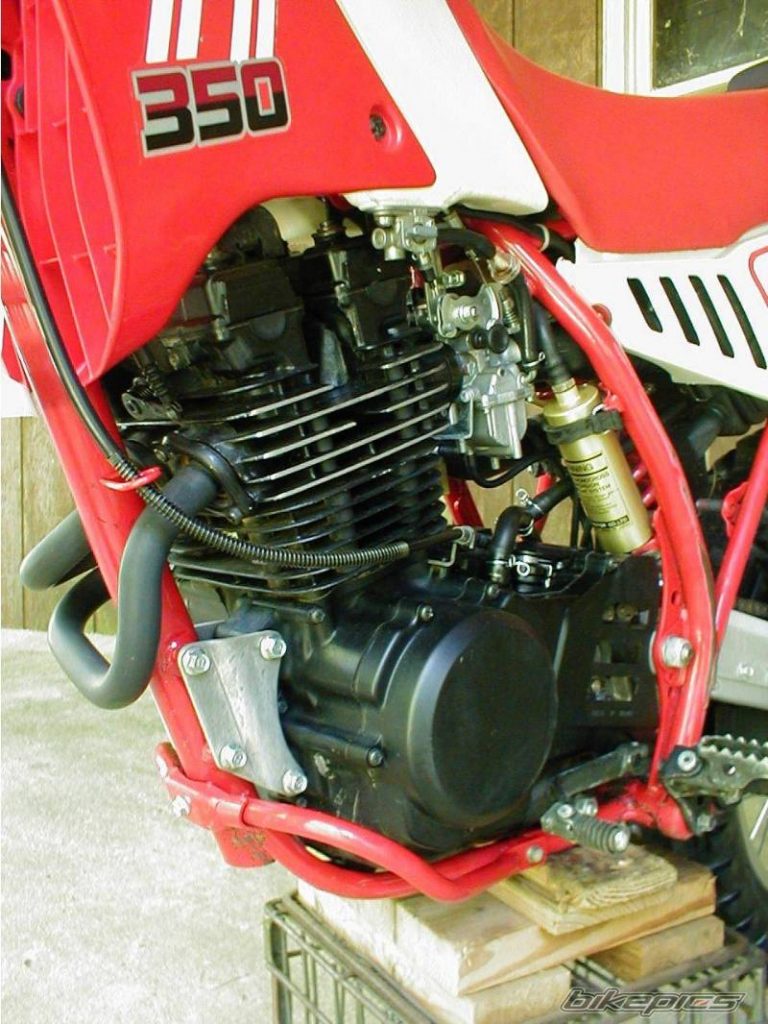

The TT350’s 346cc DOHC four-stroke mill was based on the motor found in their popular XT350 dual-sport. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The TT350’s 346cc DOHC four-stroke mill was based on the motor found in their popular XT350 dual-sport. Photo Credit: Yamaha

After six years of loyal service and virtually no updates, the original TT500 was finally retired by Yamaha in 1981. While its simple and powerful four-stroke single continued to be competitive, its mid-seventies chassis had fallen far behind the latest in motocross and off-road design. After a year-long hiatus, Yamaha’s big-bore thumper was back for 1983 with a completely new and up-to-date redesign. Rechristened the TT600, this new machine brought Yamaha’s four-strokes into the new decade with an all-new motor, redesigned chassis, and majorly-upgraded suspension. Overall displacement was boosted to a full 595cc and the chassis was given a serious makeover by bolting on a set of beefy 43mm front forks and grafting on a version of the Monocross single-shock rear suspension system found on the YZs. Big, powerful, and rugged, the TT600 proved a perfect competitor to Honda’s hugely popular XR500R.

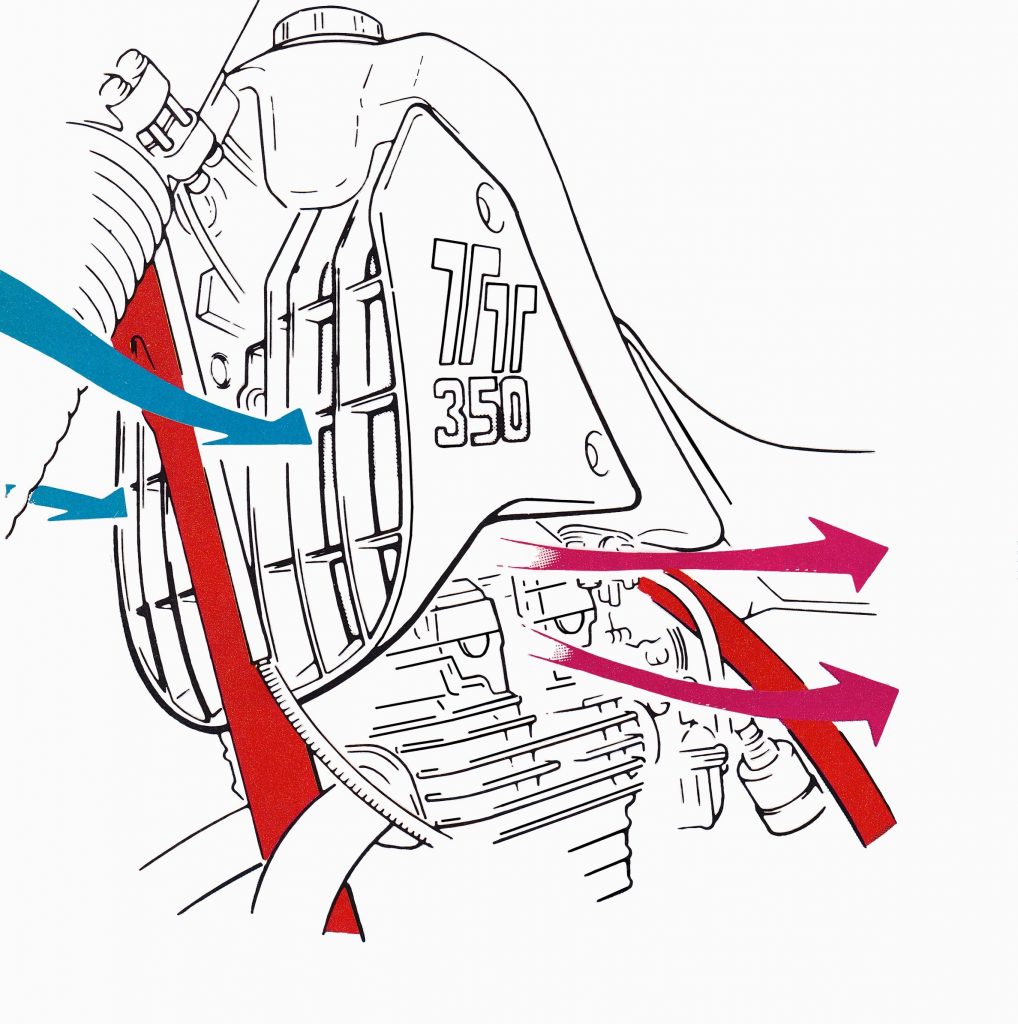

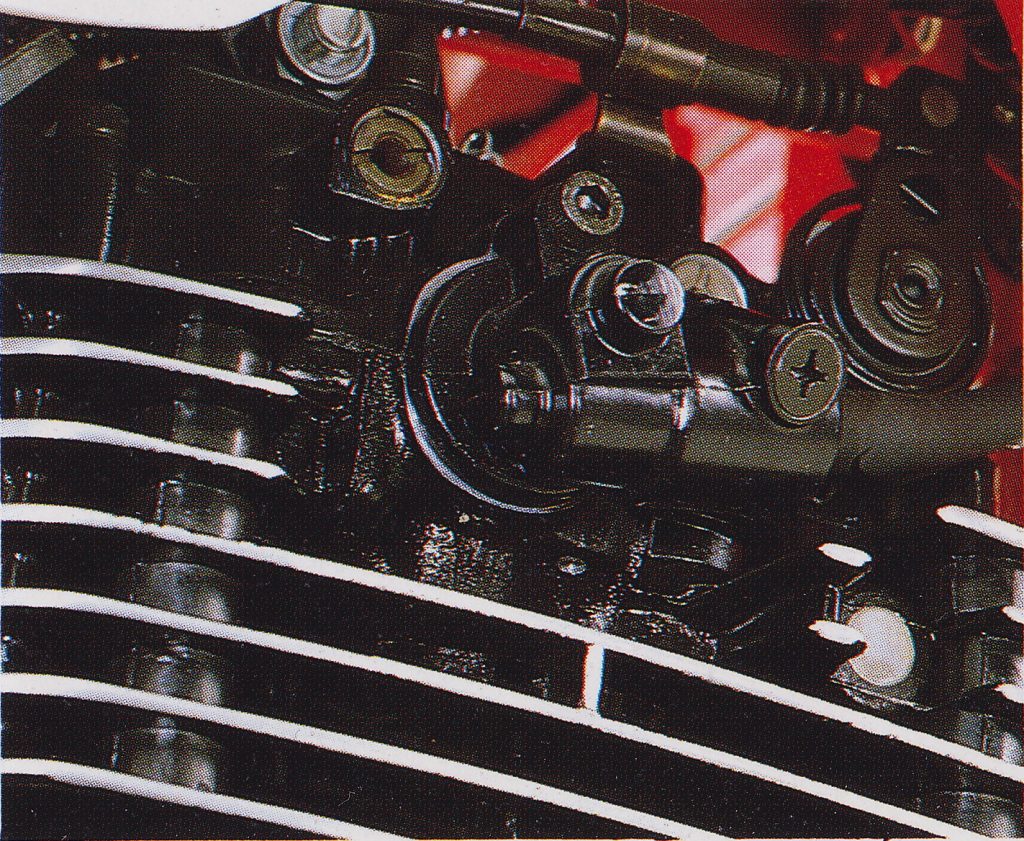

While the TT350’s motor lacked liquid-cooling, Yamaha was careful to learn from the overheating issues that plagued early Honda XRs and designed a set of substantial cooling vents into the TT’s tank to keep fresh air flowing to the Yamaha’s head. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While the TT350’s motor lacked liquid-cooling, Yamaha was careful to learn from the overheating issues that plagued early Honda XRs and designed a set of substantial cooling vents into the TT’s tank to keep fresh air flowing to the Yamaha’s head. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In 1983, another four-stroke machine made its debut on the scene in the form of Honda’s all-new XR350R. More than just a down-sized XR500R, the new 350 looked to combine the best traits of the nimble XR250R and desert-ready 500 into one package. With a strong torque curve and lighter weight than the big-bore thumpers, Honda’s new 350 proved a very popular machine with riders who found the 500 too burly and the 250 too tame.

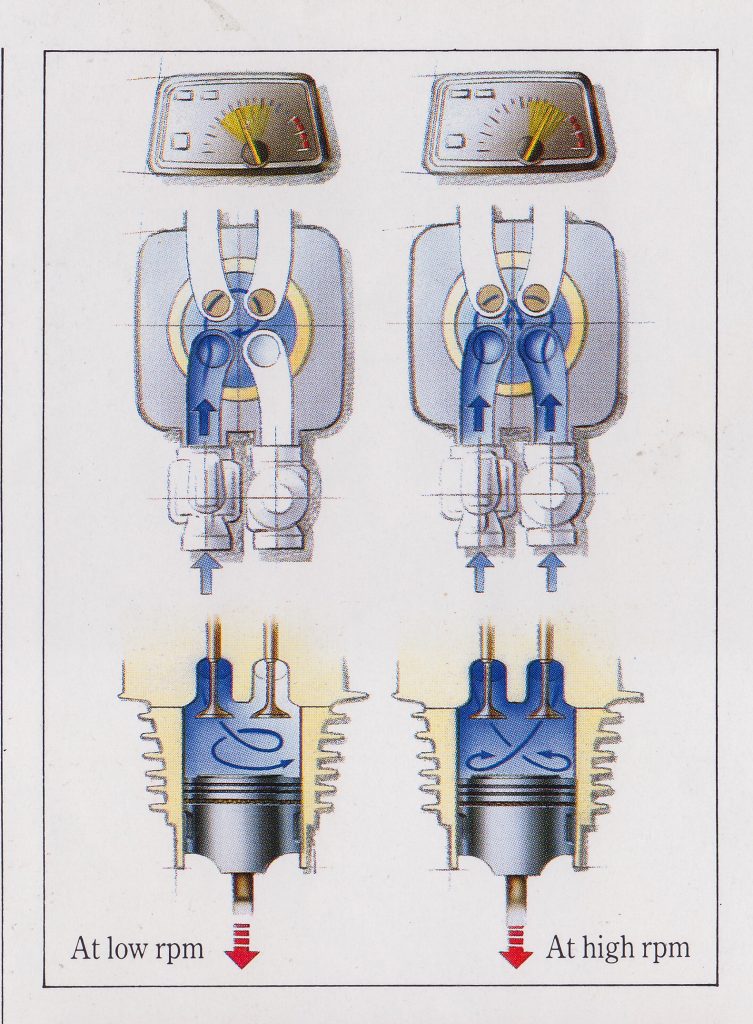

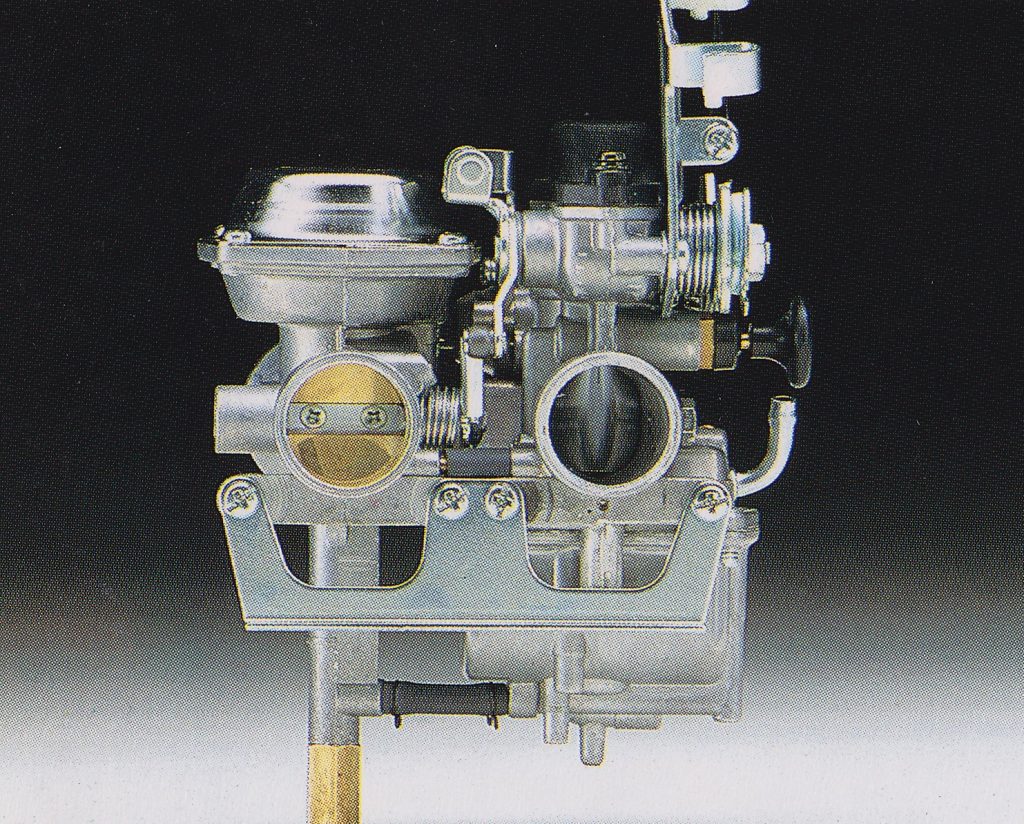

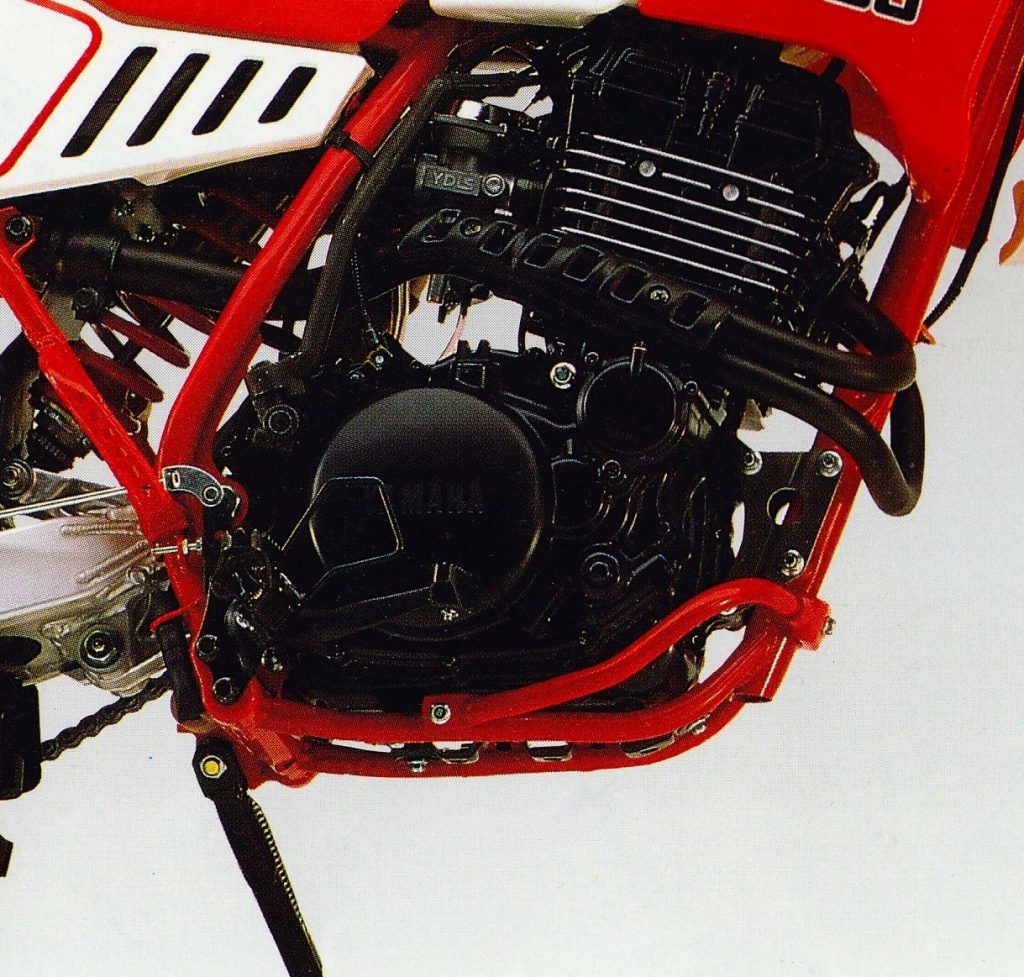

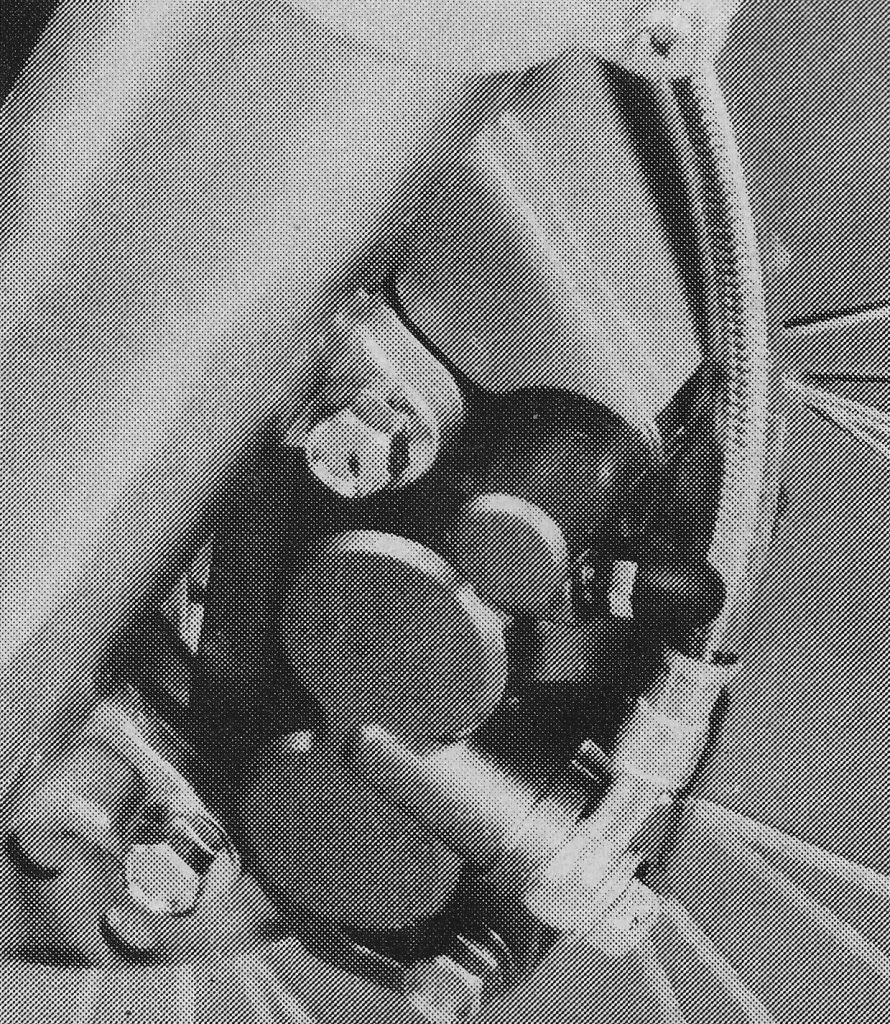

In the days before fuel injection, it was often difficult to design a single four-stroke carburetor that could provide good low-end response while also flowing enough fuel at high rpm to provide strong top-end performance. To combat this, Yamaha employed a dual carburetor arrangement on the TT350 they coined the Yamaha Dual Intake System (YDIS). By using two carburetors working in tandem the YDIS was able to provide the TT with an excellent low-end response and a wide powerband. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In the days before fuel injection, it was often difficult to design a single four-stroke carburetor that could provide good low-end response while also flowing enough fuel at high rpm to provide strong top-end performance. To combat this, Yamaha employed a dual carburetor arrangement on the TT350 they coined the Yamaha Dual Intake System (YDIS). By using two carburetors working in tandem the YDIS was able to provide the TT with an excellent low-end response and a wide powerband. Photo Credit: Yamaha

After three years on the market, Honda decided to retire the XR350R after the 1985 season. At the time, this was a surprising move with the 350 receiving a very well-regarded redesign for the ’85 season. This update had addressed nearly all of the issues riders had voiced about the ’83-84 version and had made the XR350R Honda’s most-effective four-stroke racer in the minds of many.

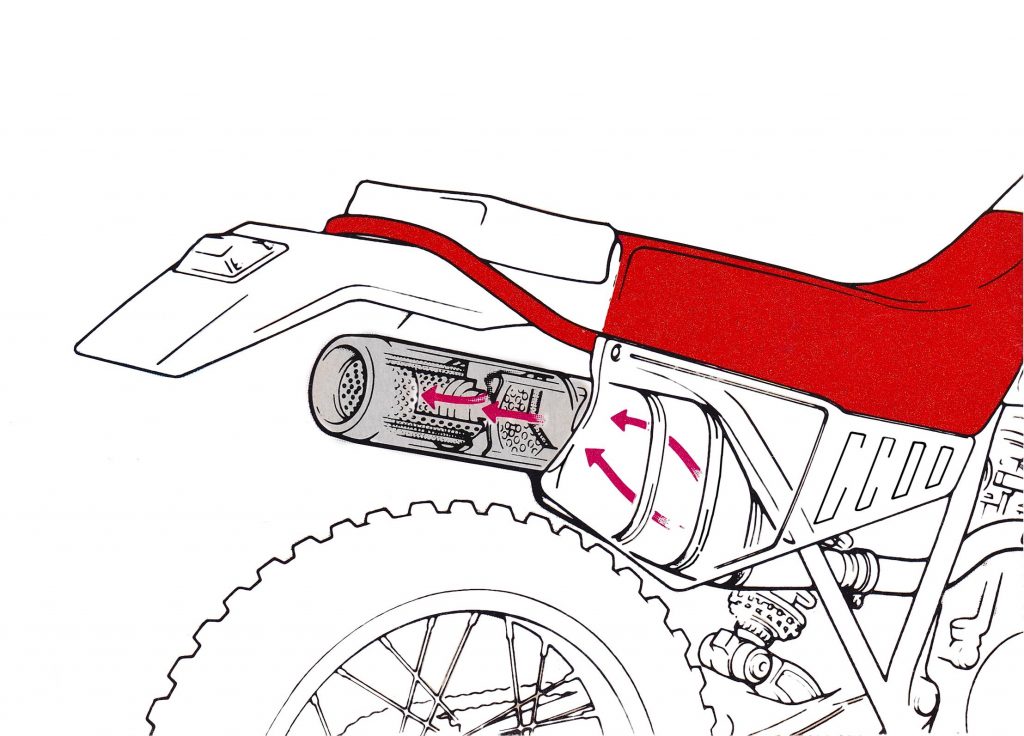

The TT350’s spark-arrested stock steel exhaust was heavy, but at least it provided an inoffensive exhaust note and solid power. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The TT350’s spark-arrested stock steel exhaust was heavy, but at least it provided an inoffensive exhaust note and solid power. Photo Credit: Yamaha

With Honda abandoning the mid-size four-stroke market for 1986, the door was left open for one of their competitors to fill that void. In 1985, Yamaha had dipped their toe into the midsize market with a dual-sport machine they coined the XT350. While not as serious or high performance as the XR, the new XT fit nicely between the underpowered 250 dual-sports and big and lumbering 600s. It was capable of hitting 90mph on the highway and far more pleasant than the buzzy small-bores once the road opened up.

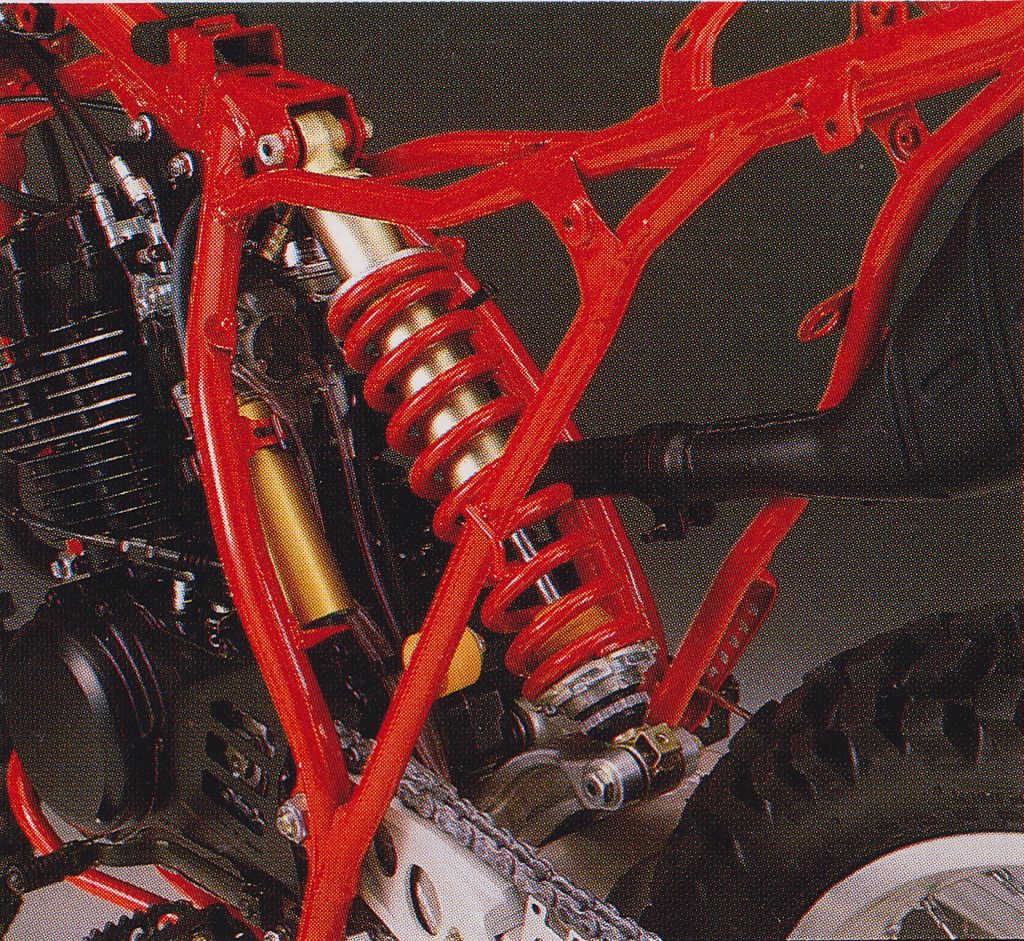

The rear suspension on the new TT350 used a single Showa damper mated to an older version of Yamaha’s Monocross linkage system. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The rear suspension on the new TT350 used a single Showa damper mated to an older version of Yamaha’s Monocross linkage system. Photo Credit: Yamaha

For 1986, Yamaha looked to capitalize on Honda’s departure by introducing an all-new mid-size thumper based around the motor in its popular XT350. Dubbed the TT350, this new machine mated a modified version of the four-stroke single found on the XT to an all-new off-road specific chassis. By using a combination of motocross and dual-sport technology, Yamaha hoped they could create the ultimate mid-size four-stroke.

A built-in compression release made starting the TT350 an easy affair. Photo Credit: Yamaha

A built-in compression release made starting the TT350 an easy affair. Photo Credit: Yamaha

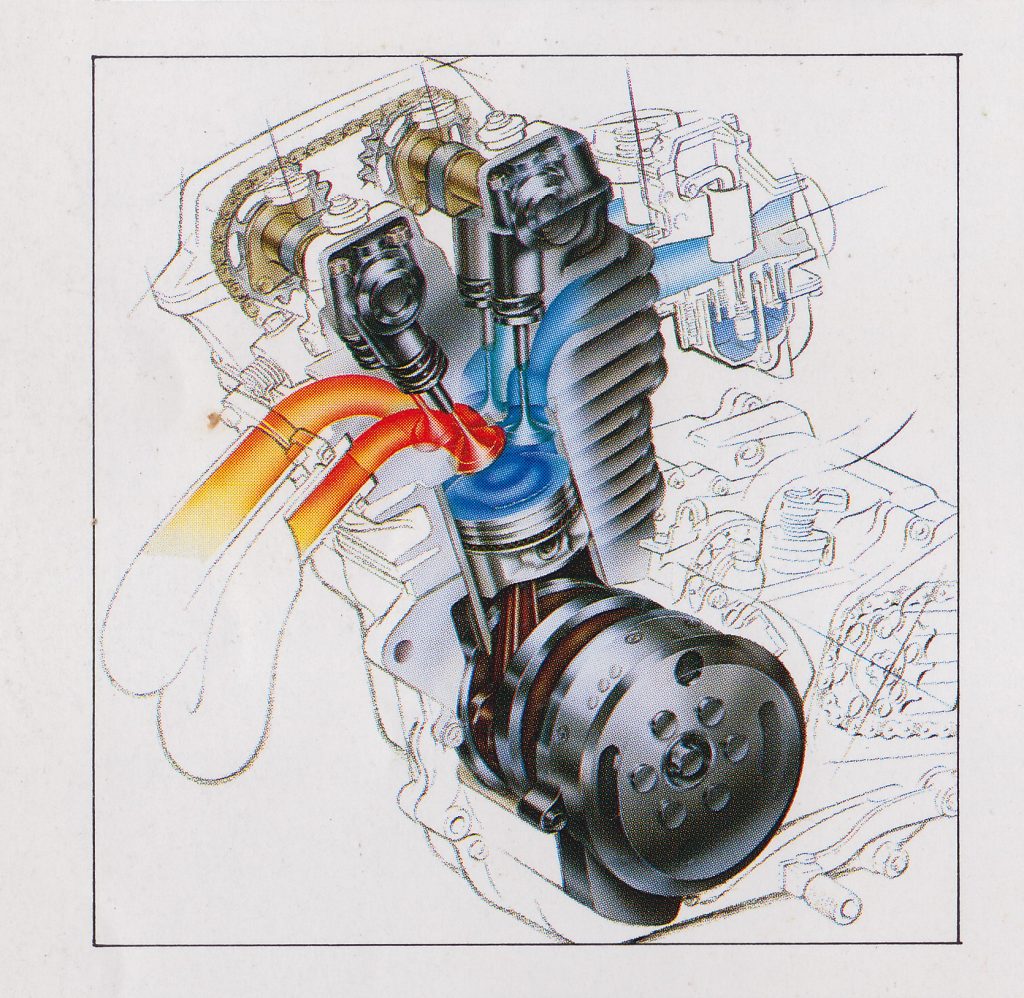

As with any off-road machine, the heart of the new TT350 was its 346cc four-stroke power plant. Like Honda’s XRs, the new TT eschewed liquid cooling in favor of a lighter and simpler air-cooled design. The motor featured an 86.0 x 59.6 mm bore and stroke and 9.0:1 compression ratio which was slightly lower than the 9.5:1 found on the outgoing XR350R. The TT350’s stroke was also slightly shorter than the ‘85 Honda’s. Like the XR, the TT employed a four-valve head with two valves for intake and two for exhaust. Where the two differed was in the actuation of those valves. On the Honda, a single overhead cam (SOHC) was used in their patented Radial Four Valve Combustion (RFVC) configuration. On the Yamaha, a more traditional dual overhead cam (DOHC) arrangement was employed with the fuel being provided by a pair of dual Teikei Kikaki carburetors through Yamaha’s Dual Intake System (YDIS).

A pair of Teikei Kikaki carburetors handled the mixing duties on the new TT350. Photo Credit: Yamaha

A pair of Teikei Kikaki carburetors handled the mixing duties on the new TT350. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The YDIS was a unique intake design that Yamaha devised to broaden the motor’s effective power band by optimizing the amount of fuel delivered based on the engine load. At low rpm, only one carburetor and intake runner were activated to prevent too much fuel from being dumped into the cylinder and causing a bog. As the motor’s load increased, the intake vacuum would engage the second carburetor and intake runner to deliver additional fuel for increased top-end power. By fine-tuning this dual carburetor system, the Yamaha engineers were able to combine the low-end response of a smaller carburetor with the strong pull of a larger mixer.

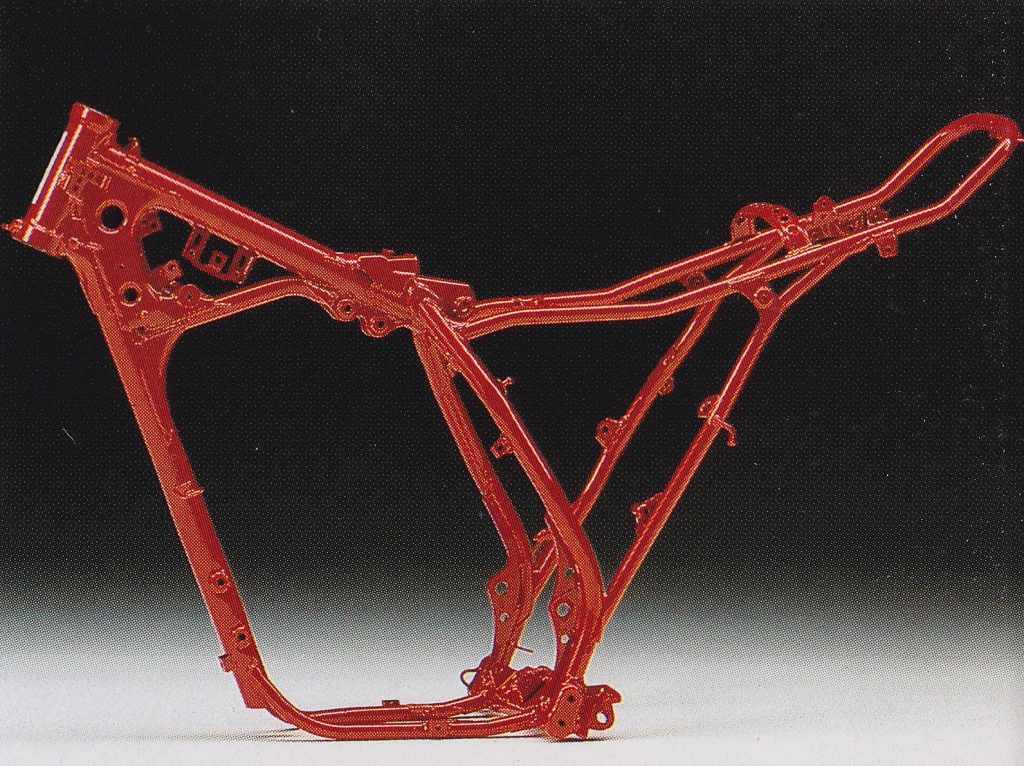

The high-tensile steel frame on the TT350 shared much of its design with the older YZ line. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The high-tensile steel frame on the TT350 shared much of its design with the older YZ line. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In addition to the YDIS, the new motor featured a counter-balancer to quell vibration and a convenient automatic decompression system to aid starting. While the motor was air-cooled, Yamaha did incorporate a pair of substantial ram-scoops below the fuel tank to help keep engine temperatures under control. Because the new TT350 carried all of its oil inside the motor as a “wet sump” configuration this was of critical importance. This allowed the motor to be simpler and lighter than a “dry sump” design, which used a remote tank for oil storage but also tended to run much hotter under heavy use. This had been an issue with the early Honda XR350s and Yamaha hoped to avoid the expensive failures some XR owners had experienced by funneling more cool air to the TT’s head.

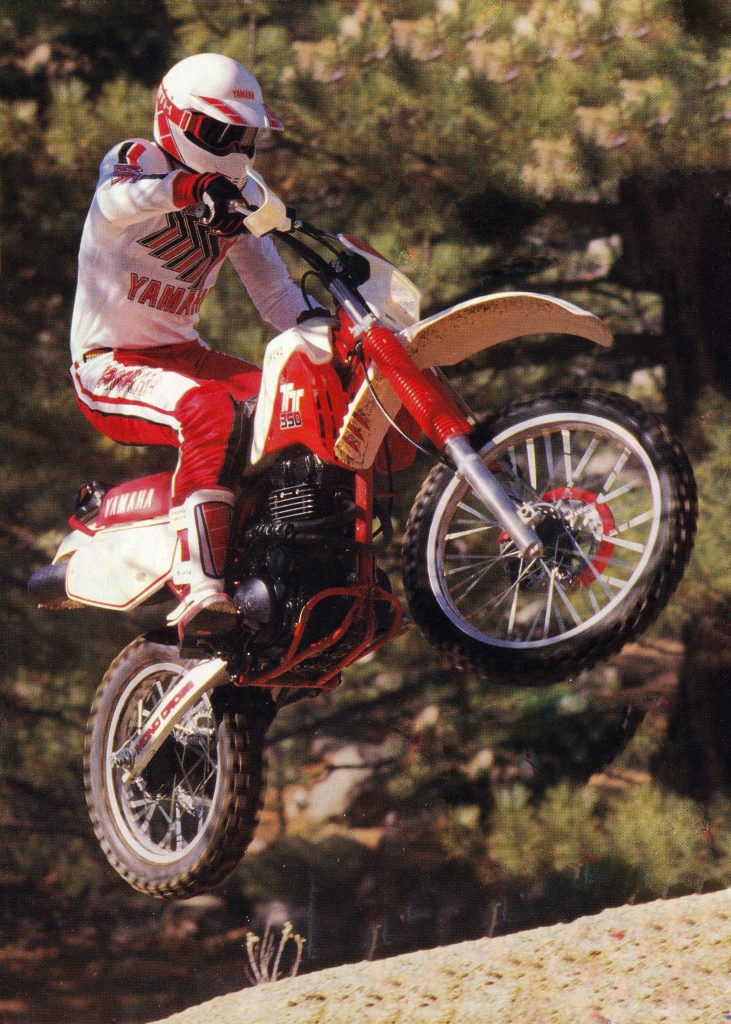

With just shy of 26 horsepower on tap the TT350 was no rocket ship but it was super torquey and quite fun to ride. Low-end power was particularly strong and the bike was more than capable of handling most anything a potential TT rider was likely to throw its way. Photo Credit: Bike Pics

With just shy of 26 horsepower on tap the TT350 was no rocket ship but it was super torquey and quite fun to ride. Low-end power was particularly strong and the bike was more than capable of handling most anything a potential TT rider was likely to throw its way. Photo Credit: Bike Pics

In the transition from the XT to the TT, the off-road version’s motor received a few significant upgrades. Both the intake ports were enlarged slightly and new valves were installed that tapered more significantly to increase flow. New cams were installed that featured a more aggressive profile and the carburetors were re-tuned to deliver additional fuel on demand. The TT’s electronic ignition was also recalibrated to work with more aggressive power settings. Internally, the motor retained the XT’s six-speed transmission and manual clutch but new ratios were added to better suit the TT’s intended use. All the gear sets were also beefed up in anticipation of the more aggressive riding the TT was likely to endure.

By using bash bars instead of a full skid plate, Yamaha’s engineers were able to protect the TT’s vulnerable engine cases without causing excess mud build-up. Photo Credit: Yamaha

By using bash bars instead of a full skid plate, Yamaha’s engineers were able to protect the TT’s vulnerable engine cases without causing excess mud build-up. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the chassis side, the new TT350 featured a frame very similar to what was being offered on the YZs the year before. The frame was constructed of stout high-tensile steel and featured a single downtube that split into a full cradle on the underside of the motor. Below the motor, Yamaha added a set of steel bash bars that offered additional crash protection without the mud-catching issues of a full skid plate. Like the YZs, the new frame lacked any sort of removable rear subframe to aid shock maintenance.

With smooth tractable power, a well-sealed airbox, and plush suspension, the TT350 was the perfect machine for creek storming missions in 1986. Photo Credit: Mark Kariya

With smooth tractable power, a well-sealed airbox, and plush suspension, the TT350 was the perfect machine for creek storming missions in 1986. Photo Credit: Mark Kariya

The shock itself was a gas/oil Showa unit that offered 11.0-inches of travel and 20 selectable settings for rebound control. Less sophisticated than the units found on the motocross line, the TT’s new damper lacked any sort of external adjustment for compression damping and did without the Brake Actuated Suspension System (BASS) found on the YZs. Mated to the shock was Yamaha’s Monocross rising-rate linkage system. Unlike the full-size YZs which adopted a new bottom-link Monocross for 1986, the TT350 made do with an updated version of the older top-link design that Yamaha had been using since 1983. Owing to its intended use as an off-road machine, the TT did receive a helpful set of zerk fittings throughout the linkage to keep everything working smoothly. Finishing off the rear suspension was a lightweight alloy swingarm with a quick-release axle design to aid trail-side repairs.

The 41mm non-cartridge Showa forks found on the TT350 were smaller and less sophisticated than what you would have found on the YZs of the time. Other than air pressure, there was no external adjustment available to dial in their performance. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The 41mm non-cartridge Showa forks found on the TT350 were smaller and less sophisticated than what you would have found on the YZs of the time. Other than air pressure, there was no external adjustment available to dial in their performance. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the fork side, the ’86 TT350 once again got an inferior version of the hardware found on the motocross line. By 1986, all the manufacturers had moved to a 43mm fork on all of their motocross machines. At the time, this size was believed to offer the optimal combination of comfort and flex resistance. On the TT350, however, Yamaha decided to save a little money by employing a set of 41mm Showa non-adjustable forks to handle the front suspension duties. Without any external adjustments for compression or rebound, fork fine-tuning was limited to air pressure (as a supplement to the coil springs), oil level, and oil viscosity.

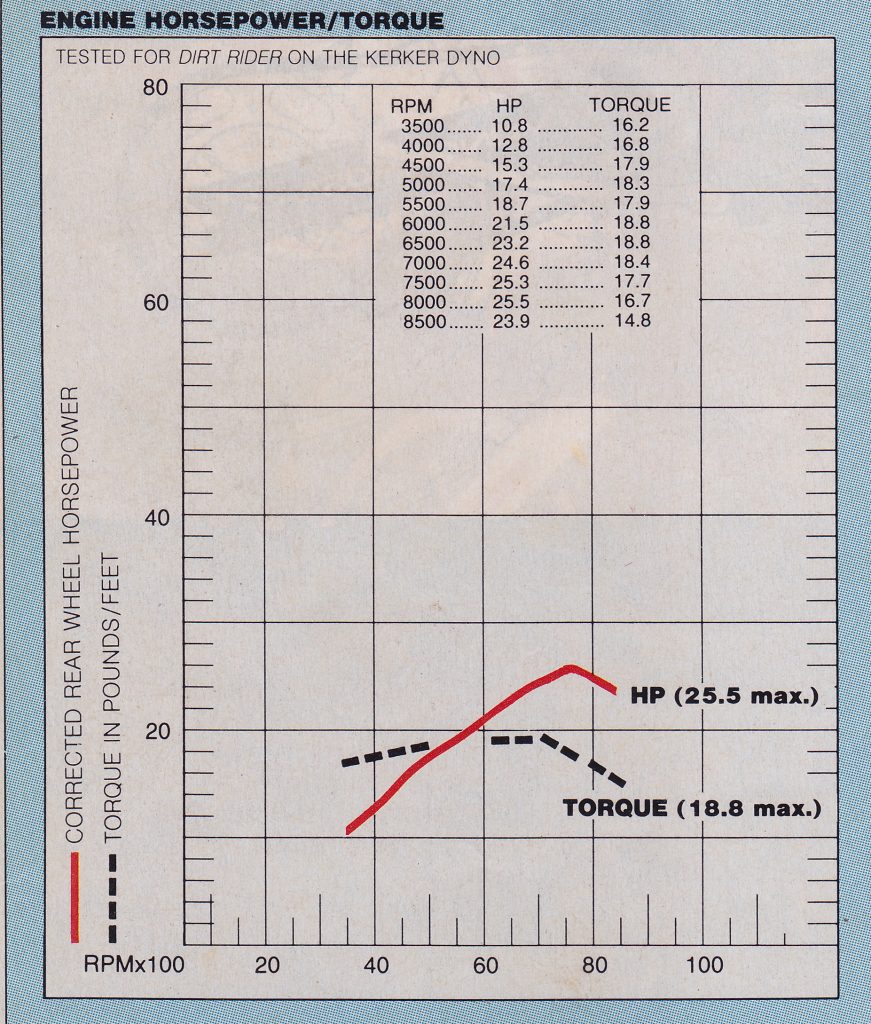

The stock TT350’s 25.5 horsepower was less than what strong-running 125s like Honda’s CR produced in 1986. Just as today, however, it was the four-stroke’s strong torque advantage that told the true story. Here, the 350’s super flat torque curve gave it a rideability advantage over the peakier but more powerful two-strokes. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

The stock TT350’s 25.5 horsepower was less than what strong-running 125s like Honda’s CR produced in 1986. Just as today, however, it was the four-stroke’s strong torque advantage that told the true story. Here, the 350’s super flat torque curve gave it a rideability advantage over the peakier but more powerful two-strokes. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

While the new TT350 was certainly not at the cutting edge of off-road design in 1986, it did prove a very capable successor to the mantle vacated by Honda’s XR350R. With 25.5 horsepower and 18.8 ft-lb of torque on tap the TT was certainly no rocket but it was fun, easy to ride, and reasonably fast for a mid-size four-stroke of the time. Compared to the outgoing XR350R, the TT’s new motor felt stronger down low, dead even through the middle, and a shade weaker on top. On Kerker’s dyno, the two were a dead heat, but on the trail the TT’s stronger low-end response made it feel decidedly perkier than the Honda.

The TT350’s strong low-end power and quick rebound made rock-hopping easy business in 1986. Photo Credit: Mark Kariya

The TT350’s strong low-end power and quick rebound made rock-hopping easy business in 1986. Photo Credit: Mark Kariya

In the real world of rocks and roots, the TT provided a very competitive Enduro powerband. While no match for hard-core two-stroke off-roaders like the KTM 350 MX/C, the TT was more than capable of keeping up with most other machines it was likely to encounter on the trail. Big hills and deep sand were no issue and the TT could make quick work of climbs that would leave an XR250R rider searching for another downshift. In the tight woods, the TT was an excellent companion, delivering gobs of smooth power that hooked up and pulled the Yamaha over slimy rocks and slippery logs with ease. By modern four-stroke standards, the TT’s power was super mellow and slow-building, but this was not an issue in 1986. At the time, people expected their four-strokes to be smooth, mellow, and bulletproof, and the new TT offered all that in spades.

Most riders praised the power and feel of the TT’s dual-piston front disc brake, but the rear drum’s action was less impressive. Thankfully, the motor’s heavy engine braking could be used to supplement its somewhat anemic performance on long downhills. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

Most riders praised the power and feel of the TT’s dual-piston front disc brake, but the rear drum’s action was less impressive. Thankfully, the motor’s heavy engine braking could be used to supplement its somewhat anemic performance on long downhills. Photo Credit: Dirt Rider

For riding out West, the TT350’s rather modest max power output made machines like Honda’s XR600R and Yamaha’s TT600 seem like a better choice for high-speed desert work. It was fine for playing in the canyons and the occasional high-speed run, but sustained triple-digit speeds were not its forte. Keep it in its element, however, and it was a super fun and versatile machine.

Front fork performance on the TT350 was of the marshmallow variety. Both the spring rate and damping setting were too light for anything other than trail riding. If you were planning on racing the TT, some sort of performance upgrade was a must. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Front fork performance on the TT350 was of the marshmallow variety. Both the spring rate and damping setting were too light for anything other than trail riding. If you were planning on racing the TT, some sort of performance upgrade was a must. Photo Credit: Yamaha

On the suspension end of things, the new TT was a bit of a mixed bag in 1986. The 41mm Showa forks offered 11.0 inches of ultra-plush travel that gobbled up small bumps and trail detritus well but bottomed harshly once the speeds picked up. Novice riders praised its low-speed comfort but fast guys lamented its utter lack of high-speed control. Large whoops and even minor jumps were too much for its soft springs, light damping, and flexy 41mm stanchions. At any sort of race pace, the forks wallowed and clanked as the overworked springs collapsed under the TT’s 260-pound girth. If you backed it down to a more sedate pace, they worked well enough, but if you had any intention of bombing across the desert or doing a little track day play, then you were going to want to get things beefed up.

The Monocross rear suspension on the TT350 was far better set up than the forks. The spring rate and shock settings were in the ballpark for the type of riding the bike was intended for and most riders liked its plush action. Photo Credit: Yamaha

The Monocross rear suspension on the TT350 was far better set up than the forks. The spring rate and shock settings were in the ballpark for the type of riding the bike was intended for and most riders liked its plush action. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Out back, the situation was better with the old-school Monocross providing a far more controlled ride than the forks. While the Showa damper was still set up softly, it did not fall completely apart when pushed. The spring rates and overall damping were well-suited to the bike’s intended use and as long as you did not go crazy trying to motocross it, the shock worked well. On the trail, it was super plush and provided the kind of all-day comfort you would expect from a Japanese off-road machine.

On the handling front, the TT350 was fairly nimble for a 260-pound four-stroke. The soft suspension, hefty weight, and prodigious engine braking provided excellent front-end traction and the bike had no trouble snaking through tight tree sections. In high-speed turns, however, the underdamped forks held the bike back and made it difficult to trust what the front end was doing. Because of its large and tall motor, the TT also felt more top-heavy than most two-strokes. At low speeds, this was not much of an issue, but you could sense the machine’s significant mass and strong gyroscopic effect if you tried to pick up the pace. While this made the bike hard to knock off course, it was also far more difficult to bring it back in line once it went astray. Riders accustomed to riding XRs and other four-strokes did not have much of an issue with these traits but pilots coming off of lightweight two-strokes were often put off initially by the TT’s more deliberate feel.

While the TT350 was a decent flier for a hefty machine, its soft forks made landings a wrist-busting affair. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

While the TT350 was a decent flier for a hefty machine, its soft forks made landings a wrist-busting affair. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike

On the detailing front, the TT350 was very well-appointed for its time. With its large 2.5-gallon fuel tank and standard 55-watt halogen headlight, the bike could be ridden all-day without fear of being stranded after dark. The motor proved utterly bulletproof and was happy to run for a decade or more with only minimal maintenance. The quick-pull rear axle and standard tool pouch made trail-side repairs easy and standard guards for the rider’s hands and front disc kept tree limbs and bushes from fouling the works. Little touches like the TT’s case-saver clutch guard, trip meter, and zerk fittings were all bonuses that made living with the TT350 pleasant and easy.

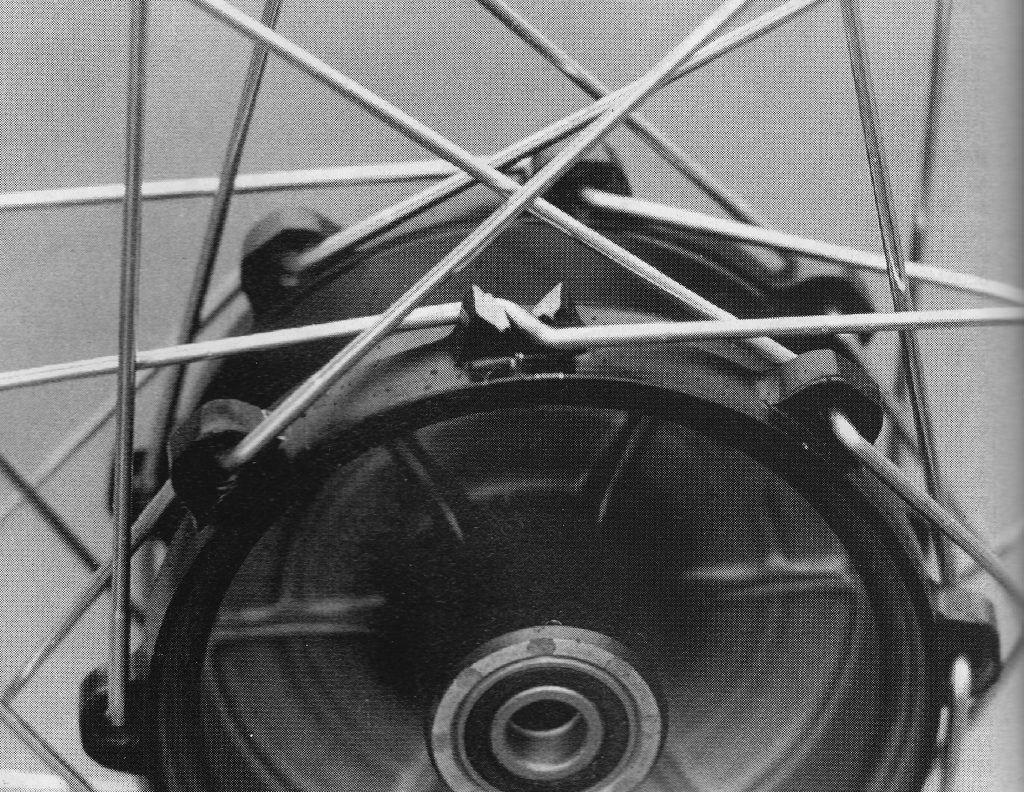

One item that the TT inherited from the YZ line that probably should have been round filed was Yamaha’s “Z-spoke” hub. While innovative, this design proved fragile and prone to cracking at the point where the spokes crossed through the hub. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

One item that the TT inherited from the YZ line that probably should have been round filed was Yamaha’s “Z-spoke” hub. While innovative, this design proved fragile and prone to cracking at the point where the spokes crossed through the hub. Photo Credit: Motocross Action

On the downside of the TT equation were the “Z-Spoke” hubs it inherited from the YZs which tended to break under hard use, the underpowered rear drum brake, and marshmallow front forks. While most riders praised the TT’s comfortable and attractive new bodywork, nearly everyone panned its old-school “banana” seat, which trapped the rider in one position and made sliding fore and aft a chore. Thankfully, this scooped-out style saddle had been retired with the ’86 YZ redesign, but the TT had to suffer on with this vestige from the past. At least the foam was fairly comfortable.

While an excellent overall machine, the TT350 would only last two years in Yamaha’s US Enduro lineup. Much like the XR350R, the TT350 would be unceremoniously dropped from Yamaha’s off-road offerings after the 1987 model year. Photo Credit: Yamaha

While an excellent overall machine, the TT350 would only last two years in Yamaha’s US Enduro lineup. Much like the XR350R, the TT350 would be unceremoniously dropped from Yamaha’s off-road offerings after the 1987 model year. Photo Credit: Yamaha

Overall, the 1986 Yamaha TT350 turned out to be a perfect successor to Honda’s dearly-departed XR350R. For riders looking for more beans than the XR250R but not as much tonnage as an XR600R or TT600, the TT350 made an attractive case. It was torquey, moderately fast, fun to ride, and stone reliable; the very definition of a mid-eighties Japanese thumper. It was a bit too slow, too soft, and too heavy for hardcore racing but perfectly aligned with its core mission as a go-anywhere, do-anything, valve-and-cam jack-of-all-trades.

For your daily dose of old school moto goodness, make sure to follow me on Instagram and Twitter @tonyblazier

For questions or comments, feel free to drop me a line anytime at TheMotocrossVault@Gmail.com