For this edition of Classic Steel, we are going to look back at a motorcycle that changed the motocross world; the 1998 Yamaha YZ400F.

By: Tony Blazier

The thump heard round the world: The 1998 YZ400F was such a shock to the motocross industry that none of Yamaha’s Big Four competitors would even offer a direct competitor for five more years. It was a tremendous technological achievement and the start of a new four-stroke revolution. Photo Credit: Yamaha

In the summer of 1997, Yamaha shocked the motocross community by announcing their intention to release a production version of their amazing YZM400 works racer. Amazingly, this was only a few months after the works version had made its debut. Such a quick turn around from works to production was truly remarkable in light of all the new technology the bike would make use of. Only nine months after Doug Henry had made his debut on the works version, you would be able to walk out of a Yamaha dealership with the highest tech four-stroke ever to put wheels to dirt. Even more incredibly, the revolutionary new machine was largely the vision of one man.

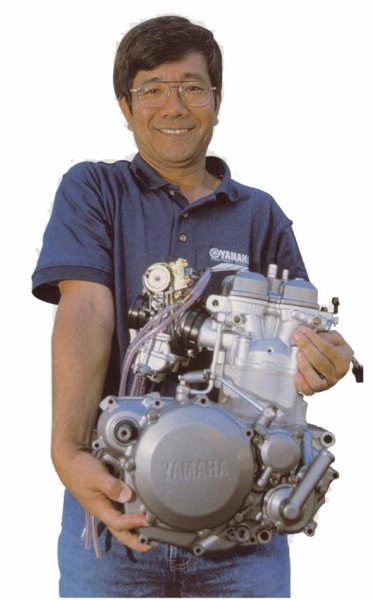

|

| The original YZ400F was the brainchild of this man, Yoshiharu Nakayama. Nakayama, a Yamaha engineer, designed and built the first YZF prototype in his spare time. Incredibly, three years later he would do it all over again with his design for the amazing YZ250F. Photo Credit: Motocross Action |

In the mid-nineties, Yamaha engineer Yoshiharu Nakayama had the ingenious idea to make use of Yamaha’s extensive road racing technology to help develop an all-new motocross machine. His idea was to take one of Yamaha’s successful YFZ road race motors, shrink it down to one cylinder, and then cram that into a YZ250 chassis. This was a very bold idea at the time, due to the fact that off-road four-strokes typically used more rugged, low-tech designs. These motors were usually in a mild state of tune and eschewed the high rpm common to road bikes. Nakayama’s idea was to forgo this old school approach, and instead pack his new machine with all the tricks Yamaha had learned building super high-performance street machines.

|

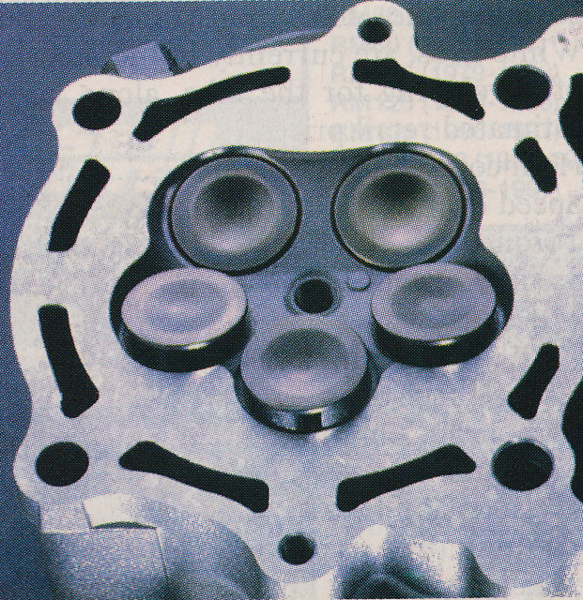

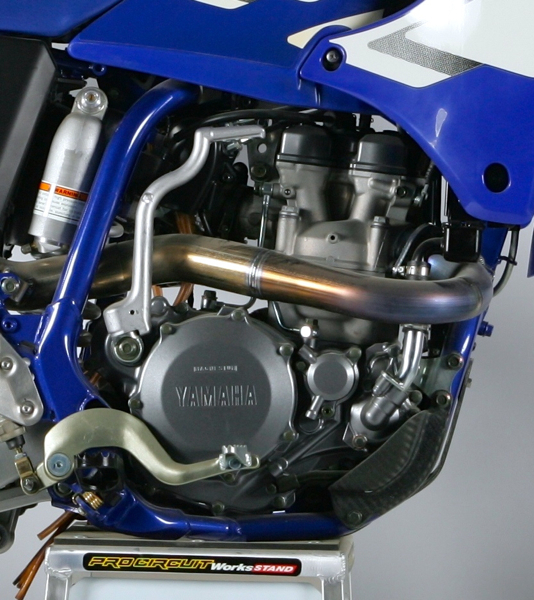

| One of the keys to the first YZ400F’s success was its incredible motor. Nakayama borrowed heavily from Yamaha’s extensive road race knowledge in designing the new machine’s high-tech motor. The YZF used a five-valve Genesis head from an FZR street bike and super lightweight components to give the bike a then unheard of 11,000-rpm rev ceiling. Photo Credit: Yamaha |

Perhaps the most amazing part of all of this is the fact that Nakayama took on the task of designing this new machine all on his own. His pet project was undertaken on his own time, on evenings and weekends. Once he had worked out the design for his new Frankenstein machine, he enlisted two additional co-workers to help him build a working prototype. Remarkably, a staff of three people tinkering on their own time created the bike that changed motocross history.

| If you wanted to race a four-stroke in the mid-nineties you had two choices. Buy a cobby Euro bike like this Husaberg or build one yourself out of an enduro bike. No matter which route you chose, you would end up with a godawfully expensive and unreliable money pit. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

Yamaha was so impressed with Nakayama’s prototype that they greenlit a works version to be built. In anticipation of the new bike, Yamaha requested a one-year exemption from the AMA production rule, and in 1997 Doug Henry and Andrea Bartolini raced the prototype YZM400 both here and in Europe. The YZM400 turned out to be a huge public relations windfall for Yamaha. The YZM graced the cover of every magazine in the industry, as the public lusted for any information about the exotic machine. Capitalizing on this heightened interest, Yamaha announced that they would indeed be building a production version in 1998.

|

| If you did not want to go the Old World route, you could always build your own. In the mid-nineties, there was actually quite a cottage industry devoted to turning mild-mannered XRs and KLXs into fire breathing racers. This KLX built for 1990 125 SX champ Ty Davis is a perfect example of the exotic bikes being turned out at the time. You could easily spend double the cost of a new bike trying to transform these play bikes into something competitive. Photo Credit: Dirt Bike |

At the time Yamaha announced its new racing four-stroke, the world of thumpers was very different. In 1997, four-stroke motorcycles were still largely considered toys. Even though brands like Husaberg, VOR and Husqvarna were building four-stroke motocross bikes, these machines were odd, unreliable, and out of the price range of most mortals. At the other extreme, you had the loons who liked to spend thousands trying to turn their mild-mannered XRs and KLXs into motocross bikes. These daring tinkerers usually ended up with overheating hand grenades for all their trouble. The YZ400F would truly be the first machine to combine the performance of the exotics with the affordability, quality, and dependability of the Japanese.

|

| The YZF motor used chain-driven dual-cams to actuate its five valve head (three intakes an two exhausts). The valves themselves were activated directly by the cams, eliminating the additional weight and complexity of traditional rocker arms. In addition to the lightweight valvetrain, Yamaha employed a slipper piston (a super lightweight piston consisting of little more than a crown and tiny side skirts) to cut down friction and reciprocating mass. Photo Credit: Stephan LeGrand |

The thing that really made the YZF special was its incredible motor. Nakayama hit it out of the park with his ingenious idea to take Yamaha’s high revving Genesis road race motor and cram it in a YZ chassis. The new YZ400F ran, unlike any other four-stroke before it. The YZF’s most unique feature was its five-valve Genesis head, first pioneered on Yamaha’s FZ750 a decade before. The high flow head design was mated to a super lightweight slipper piston and very short stroke configuration to give the bike a very free revving feel. The head did away with power robbing (and rpm limiting) features like rocker arms and made use of lightweight alloys throughout the powertrain. Because of this, the YZF could safely rev all the way to 11,000 rpm, an almost unheard of number for off-road machines of the time.

Perhaps the biggest breakthrough on the YZF was it revolutionary road race-derived carburetor. At the time, the YZ400F’s 39mm Keihin FCR was a modern miracle in four-stroke performance. Previous to this marvelous mixer, carburation was a huge limiting factor on racing thumpers. Due to their massive intake pressures and need for instant fuel delivery, most previous four-strokes suffered from a massive bog if the throttle was opened too suddenly. Sometimes this bog could lead to a flame out, where the bike would actually cough and die unexpectedly. This was less of an issue on off-road, where throttle control was often more important than instant acceleration. On a motocross track, however, where you need instant response to handle jumps and tricky obstacles, this hesitation in power delivery can be quite an issue. Enter the amazing Keihin FCR.

|

| The secret to the YZF’s remarkable performance was this little wonder. The 39mm Keihin FCR used on the YZF was a miracle in four-stroke performance at the time. It allowed for unheard of response and preciseand carburation on the big Yamaha. It would take the advent of fuel injection to finally displace this ingenious piece of hardware. |

The FCR made use of technology acquired on the road race circuits to deliver an instant throttle response never before seen on a valve and cam machine. The FCR used a fuel pump to assure there was always fuel ready when needed and had a slide that rode on roller bearings to prevent binding under heavy vacuum. It kept track of throttle position info and relayed that directly to the ignition where adjustments could be made on the fly. Without the breakthrough in carburation the FCR provided, the modern four-stroke race bike could never have been possible.

|

| In 1998 Jody and his buddies at MXA nearly proclaimed this bike the second coming of Jesus. They loved the YZ400F and raved about it and its 426 successor for years. In my opinion, MXA and the other magazines helped promote the switch to these big, heavy (and LOUD!) machines when many people were still very much on the fence. Ironically, now they seem to be regretting this change to the big four-bangers, but I think it is way too little, way too late. |

So what was it like to ride the first YZ400F? Its 399cc Genesis power plant gave the bike a quick revving, hard-hitting, delivery that was completely unlike any four-stroke before it. Typical racing four-strokes relied on massive torque and a slow, metered delivery to get the job done. The YZ400F on the other hand, did not chug, it spooled up like a 600 sport bike. The power was almost a hybrid between a two-stroke and a traditional thumper. Some people at the time even described the YZF as a three-stroke. It had torque like and XR but revved like a CR.

|

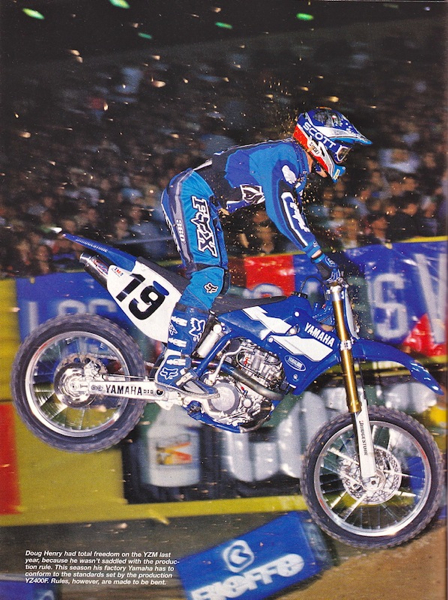

| When I first heard Yamaha was racing a thumper in ’97, I thought someone had lost his or her marbles. Then Doug Henry smoked everyone on the thing at the Las Vegas Supercross, and nobody was laughing any more. This bike was so trick it could rival the best from Honda in the 80’s. Everything on the bike was handmade and custom built. Interestingly, when you look at the YZM, it actually shares nothing at all with the production version. The motor, frame and bodywork are all completely different. Bikes like this are why the AMA needs to drop their idiotic production rule here in the USA. |

In terms of outright power, it was not awe inspiring at around 45 hp. This put it about even with the best running 250 two-strokes of the time. Where it pulled ahead was in its abundant torque and wide power curve. It started pulling much earlier and kept making that power well past the point where most 250’s were just making noise. Unlike most current 450’s, the YZ400F was not explosive. It had a smooth, electric style of power that was very easy to control. The bike was actually deceptively fast. It did not feel incredibly powerful, but in a drag race it would dust anything short of a KX500. In addition to being smoother and easier to handle overall, the four-stroke’s every other firing cycle also made the bike easier to get hooked up on slick surfaces. In the right conditions, the YZF was nearly impossible to beat.

|

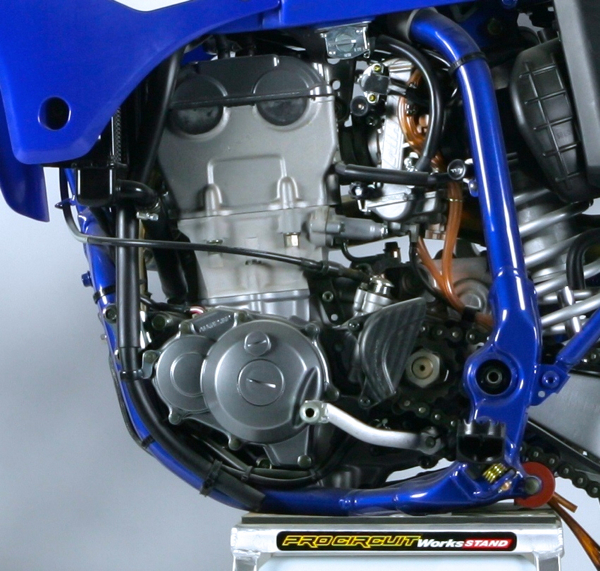

| In 1998 Henry once again volunteered to campaign the four-stroke, but this time it would be on a production based version. Amazingly, Henry almost bookended the ’97-’98 season by nearly taking home the victory in the ’98 season opener. Henry led most of the race, but with only a few laps to go stalled his big thumper and was unable to get it relit (a huge problem on these early YZF’s). It would have been a great Cinderella story, but Henry would have to wait until the outdoors to get his revenge. |

All was not perfect with the YZF, however. Perhaps the biggest issue was the fact that the bike required an elaborate ritual just to start it. This was no kick-it-and-go two-stroke, after all. The YZF required that you first find top dead center, then notch it just past TDC and engage the handlebar mounted compression release. Once that was done, you could now give the bike a full, smooth kick. If it did not fire, you had to do it all over again. If you stalled it in a race, you had to make sure you first found neutral (the bike could not be kick started in gear under any circumstances) and reach down to the carb and pull the hot start (make sure you don’t grab the choke by mistake) before even attempting the starting drill. Oh, and make sure that at NO point during all of this that you touch the throttle. If you did, the throttle pump would be engaged and the YZF would be flooded. If that happened, you might be kicking for half an hour.

|

| To say these 1st generation YZF’s were not great Supercross bikes would be putting it mildly. Their extra weight and finicky carburation were not well suited to the tricky stadium tracks. Get them on a fast outdoor track though, and watch out. Henry used his power advantage all summer to rip holeshots and lay claim to the 1998 250 National Motocross Title. It was a hugely popular win for the Massachusetts native and major redemption after his near career ending crash three years earlier. |

Once you finally got the bike running, there were still a few issues for riders unaccustomed to four-strokes. Even though the FCR carb was light years better than anything before it, there were still some residual four-stroke quirks to deal with. Compared to the lighting fast throttle response of a two-stroke, the YZF still required a measured approach to throttle application. If you suddenly wacked the throttle open as you would on a smoker, the YZF would still occasionally hiccup and hesitate. It was also not totally immune to the occasional four-stroke cough and die syndrome. Again, it was much better than previous thumpers, but still not as predictable as a good two-stroke.

|

| One of the things that helped make the YZF a huge success was its bulletproof reliability. Unlike most racing thumpers, the YZF was nearly as trouble free as a Honda XR. As long as you changed the oil regularly and kept the air filter clean the bike was nearly indestructible. When Yamaha had designed the bike, they had taken extra care to add extra oil capacity and filters to assure longevity at the cost of extra weight. Since the cost of a failure was so great, and many people were already afraid of the bikes added complexity, it was probably a good trade off. About the only notable failure on these early YZF’s was the breaking of kickstarters by riders unaccustomed to its starting eccentricities. |

Another trait new to two stroke converts was the YZF’s pronounced engine breaking. Compared to contemporary thumpers of its day, the YZF had very little of this old school trait, but if you were coming off a YZ250 it was quite an adjustment. Smart riders quickly learned to put this engine braking to good use, as it helped weight the front in turns and aided in breaking. Even so, it did require a rider to adjust his technique. The YZ400F definitely required a rider to think differently about how he attacked the track. It was not a brake-slide-in-and-blast-out kind of bike. You had to change your lines and rethink how you used your motor to get the most out of its unique power characteristics.

The rest of the YZF was far more conventional than its motor. When Yamaha went about building their new wonder thumper, they looked to their current YZ250 for inspiration. The YZF used suspension right off the YZ and copied most of its frame geometry. The main difference between the two was the added weight and size of that big tall motor. Out of the crate the YZ400F tipped the scales at 250 pounds, with fluids, that ballooned to nearly 260. That meant the YZF was a little lighter than an XR400, but nearly thirty pounds heavier than an YZ250. There really was no getting around the bike’s excess weight; it defined the overall feel of the bike and affected everything from handling to suspension.

On the handling front, the YZF was again much different than most machines of its day. Even thought the YZF shared most important chassis specifications with its two-stroke stable mates, the added weight and unique power delivery gave the bike a very different character. The engine braking and forward weight bias gave the YZF the ability of take lines no two-stroke rider could attempt. Front-end traction in turns was just remarkable and the bike was an absolute freight train at speed. In off cambers and slick turns the YZF rider had a huge advantage.

|

| The front of the YZF was plucked straight off a YZ250. Yamaha beefed up the springs and damping slightly, but it was still too soft for anyone heavy or fast. Braking was likewise slightly overwhelmed bike the bike substantial weight, but the motors natural compression breaking helped in that department. |

The flip side of this, however, was YZF’s reluctance to suddenly change direction. The bike’s weight, and the gyro affect of the big thumper made the bike difficult to throw around. In tight switchbacks, you really felt the weight, and if it got off course it was no mean feat to get it back under control. Jumping was also a bit of a trade off on the big YZF. The abundant power made major leaps a piece of cake, but if the bike got kicked sideways, it often stayed sideways. That and the sometimes-unpredictable throttle response could make tricky rhythm sections a game of Russian roulette.

Because the YZF used the highly regarded YZ suspension components, the overall performance was quite good. The only real change had been to install stiffer springs and firm up the damping. On small chop the YZF was magic, gobbling up small bumps like they were not even there. The four-strokes smooth power delivery and sizeable girth caused the bike to hook up and follow the terrain like it was on rails. In big whoops and deep sand, however, the bike could be a handful. If you mistimed a jump and landed wrong, there was no escaping all that added mass, and both ends would greet you with a metal-to-metal clank! Even with the slightly stiffer stock settings, the YZF forks were too soft for its sizeable weight. If you planned to take the bike anywhere near a modern motocross track, an upgrade in spring rates front and rear were definitely recommended.

|

| For riders accustomed to two-strokes this bike felt like it had traction control. The rear end hooked up out of turns and stayed hooked up. In the rough, its tractable power and added weight helped the bike eat up the bumps. Its only real issue was in major g-outs and hard landings, where that weight would overwhelm the stock shock and greet the rider with a resounding clank. |

The YZ400F may be the single most influential motorcycle in the history of the sport. Overnight, it changed the way a whole industry thought about four-stroke motorcycles. The bike was far from perfect, but it was a quantum leap ahead of any thumper offered before it. It was faster, better handling and perhaps most importantly, more reliable than any other racing four-stroke available at the time. If the YZF had been your typical high-strung, racing-thumper time bomb, people would have quickly soured on its charms. As it was, the bike was virtually bulletproof (and remains the most durable of the big five even today) and often more trouble free than a lot of two-strokes.

|

| It may not look like much now, but this is the bike that started it all. Like the Model T or the microwave oven, the Yamaha YZ400F was a real game changer. It changed the way people thought about four-strokes and led to a complete shift in the marketplace. This may be the most influential motorcycle ever built. |

The YZ400F took the racing thumper out of the purview of the rich and the backyard tinkerer, and moved it into the mainstream. It was the catalyst for a paradigm shift that would transform the sport in the years that followed. Whether those changes have all been for the better is still a subject of heated debate. Regardless of which side of the debate you fall on you have to admire the ingenuity and vision that went into making this bike a reality. It really is a machine that shocked the world and transformed an industry.